Abstract

Social processes behind the success or failure of collaborative implementation frameworks in African public administration contexts are under-researched. This paper addresses this gap by paying particular attention to trust attributes in collaborative implementation arrangements in Kenya. It shows how implementation challenges of policy programs and interventions may be linked to these interventions’ social characteristics in the public sector. The paper draws on a threefold approach of mutual trust and administrative data on public sector collaborative implementation arrangements for Kenyan anti-corruption policy like the Kenya Leadership Integrity Forum. Findings show that despite increased efforts to realise joint actions in public sector collaborative arrangements, they remain primarily symbolic and hierarchical and feature loose social cohesion among actors, producing challenges bordering on deficiencies in social processes of implementation. These include politicised aloofness or lack of commitment, unclear governance structures, coordination deficiencies, inter-agency conflicts, layered fragmentations, and overlapping competencies among different agencies. The paper recommends identifying and nurturing socially sensitive strategies embedded in mutual trust, like informal knowledge-sharing channels, to address primarily mandated public sector collaboration challenges in Kenya. Such efforts should consider systematic training and incentivising public managers to think outside inward-looking organisational cultures, allowing them to devise sustainable collaborative implementation approaches (promote open innovation) for policy programs, particularly anti-corruption policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While the essence of public sector collaborative governance in realising government programs has recently increased, more research is still needed to unpack the social processes driving these collaborations in practice (Minhas & Sindakis, 2021; Vallentin, 2022; Zhang, 2018). This is especially relevant today when public administration practitioners and scholars are keen on finding solutions in debureaucratised forms of public governance processes (Mokline, 2023) to order and address traditional organisational challenges (Thompson et al., 1991; Onyango, 2019a, 2019b; Gerton & Mitchell, 2019; Bianchi et al., 2021; Minhas & Sindakis, 2021; Lee, 2022; Mu & Cui, 2023). Studies on collaborative arrangements have shown that they remain critical in addressing implementation challenges like knowledge exchange deficits or bounded rationality problems, for example, through co-production and co-creation (Lauwo et al., 2022; Siddiki & Ambrose, 2023). They also assist with promoting knowledge brokerage (Kumpunen et al., 2023), reducing problems of territoriality (Barandiaran et al., 2023) and mobilising complementary resources in situations where government agencies need unique skill sets and extra help when implementing policy programs (Onyoin et al., 2022). Thus, it only makes sense that collaborative governance has often presented optimism in joint actions as an organisational method for achieving better performance in public administration.

However, research further shows that realising joint actions in collaborative arrangements does not come that easily. This is so even when public organisations are mandated to collaborate (Mu & Cui, 2023). While somehow downplaying the myriad dysfunctions public sector collaborations may produce, scholars are yet to set forth a vibrant research agenda towards conceptualising and tackling the challenges of the realising social process for collaborative arrangements (Sowa, 2008; Bianchi et al., 2021; Sipayung et al., 2023). A case in point may include the fact that collaborative governance efforts come in loosely organised and embedded forms of joint action systems in public administration (Agranoff, 2005; Percy-Smith, 2006; Stoker, 2006; Gerton & Mitchell, 2019; Lopes & Farias, 2022). This may mean that public sector collaborations can easily succumb to internal and inter-agency politics and, as such, remain too complex to realise, especially in contexts where public administration is only developing like those in some African countries.

Also, joint actions require more intentional public leadership to realise (Zhou & Dai, 2023) and sustain; an issue that is problematic in public administration and may be short-lived if realised. This being the case and notwithstanding many success stories, realising joint organisational actions characteristically bears tensions and conflicts in public management (Hudson et al., 1999; Christensen et al., 2007; Minhas & Sindakis, 2021). Furthermore, multi-agency network policy processes may acquire other complex public governance modes and approaches, which could require public managers to develop additional skill sets and resources that may not be readily at their disposal. This may be especially so in some African contexts where public administration typically works under conditions of resource scarcity that cannot fully support public innovations inherent in inter-agency collaborations (Bernardi & de Chiara, 2011; Chelagat et al., 2019; Minhas & Sindakis, 2021). Consequently, collaborative challenges have become more inevitable in public administration as they increase in scope and as government agencies deal with difficulties in creating sustainable systems, responding to the demand for innovation, and the ambiguity of goals (Agranoff, 2005; Gerton & Mitchell, 2019; Capano et al., 2022).

This paper deals with these issues in Kenyan public sector collaborative joint actions contexts where these arrangements have recently become increasingly fashionable within the public sector and levels of government. It builds on the vibrant literature on the role of trust in shaping and sustaining social processes of collaborative arrangements in public administration (Bardach, 2001; Oomsels & Bouckaert, 2014; Vallentin, 2022; Casadella & Tahi, 2022). Its analysis shows how implementation challenges of policy programs and interventions may primarily reside with deficits in social processes that inform or sustain collaborative governance approaches. Findings show that despite increased efforts to realise joint actions in public sector collaborative arrangements, challenges underpinned by social deficiencies or those that can be addressed through social processes prevail. These include politicising relations between organisational actors, lack of commitment, unclear governance structure, coordination weaknesses, inter-agency conflicts, and the fragmentation and overlapping of competencies among different agencies. This paper dissects and conceptually illuminates these issues using a multi-pronged theoretical framework for mutual trust in Kenyan contexts. Ultimately, it calls for systematic training and incentivisation of public managers to devise sustainable public sector collaborative implementation approaches to improve effective ownership and knowledge transfer for implementing policy programs, particularly anti-corruption policy.

This study is essential in understanding recent transformations in African public administration contexts. While much has been done to understand public sector collaborative arrangement outcomes, little is known about accruing difficulties in African public sector contexts. Therefore, it is unsurprising that this research agenda is still lagging in Africa, where the multi-agency implementation approach is taking root (Lauwo et al., 2022 in Tanzania; Ibrahim et al., 2023 in Ghana; Haruna et al., 2023). Much of what is known about joint action challenges refers to the European and North American experiences, as similar institutional arrangements currently proliferating in developing country contexts in Africa remain vastly under-reported. This paper is a moderate attempt to illuminate this void using trust variables as explanatory variables. It advances that collaborative arrangements functionally reside in informal (social) processes that tend to complement or glue together loosely matched legal repertoires for inter-agency interaction to foster coordination, information-sharing, planning, implementation, and collaboration (Bardach, 2001; Percy-Smith, 2006; Onyango, 2020; Ansell et al., 2022). The empirical analysis for this discussion draws on administrative data to dissect these issues in the context of anti-corruption policy implementation in Kenya. It begins by devising a multi-agency approach anchored on cognition and affective attributes of mutual trust to understand these collaborative dimensions.

The proceeding discussion is organised as follows. The next section presents the conceptual foundations of social processes in the public sector. This section also reviews relevant literature and identifies the trust composites of multi-agency relations. The presentation of this study’s inter-agency trust framework, framed within trust-informed social processes and linkages in collaborative relations, follows. This section further puts public sector collaborative arrangements in Kenya in context in light of the anti-corruption policy’s joint action arrangements like Kenya Leadership and Integrity Forum (KLIF) and National Council of Administration of Justice (NCAJ). Doing so identifies the underlying social processes, mainly administrative attitudes and organisational composites of inter-agency relations. After this is the presentation of the study’s methodology, data presentation and discussion, and conclusion sections.

A focus on the Kenyan public sector’s collaborative experience offers a relevant case of contribution to the public governance research agenda that is predominantly steeped in Western countries’ reform experiences and scholarship. Since the 2010s, the Kenyan policy landscape, like most African countries (see e.g., Casadella & Tahi, 2022; Limbu et al., 2015), has witnessed a growth in governance approaches like multi-agency relations in public policy and public service delivery (Otenyo, 2021; Onyango, 2022). As such, this paper's contribution comes at a time when research on challenges characterising the fragility and complexity of inter-agency relations in public governance in public service is growing globally. Its discussion of African contexts particularly presents insights into the practice and theory of modelling state reforms in African countries.

Conceptualising Social Processes in Public Sector Collaborations and the Role of Trust

Collaborative governance arrangement as a multi-agency network is defined as ‘any joint activity by two or more agencies working together that is intended to increase public value by working together rather than separately’ (Bardach, 1998, p. 8). It is based on the idea of a joint action, which means that ‘complex policies are more effectively put into practice if agencies cooperate a lot, whereas less difficult tasks are handled just as well without inter-organisational co-operation’ (Lundin, 2007, p. 629). Finding a functional model that effectively couples legal and non-legal or social (informal) engagement processes of such joint actions is often challenging in public administration (Bernardi & de Chiara, 2011; Chelagat et al., 2019; Christensen & Lægreid, 2019). For example, public organisations are more concerned about the loss of power that sometimes or mostly comes with organising tasks across institutional boundaries (Molenveld et al., 2020), or they tend to pursue more inward-looking organisational performance strategies that hinder effective collaboration (Onyango, 2019a).

For some time now, scholars have done a good job of trying to model such social processes behind inter-organisational collaborations (Bardach, 1998; Oomsels & Bouckaert, 2014; Amoako & Matlay, 2015; Davis, 2016; Onyango, 2020). For example, Bardach’s (1998) craftmanship model of collaboration primarily involves platforming repertoires such as creative opportunity that identifies relevant actors and resources within a collaborative arrangement. This considers dimensions of intellectual capital (the creation and application of knowledge) that involve mapping the nature and scope of the policy problem and strategic collaborative ideas. Other platforming components include acceptance of leadership and advocacy groups, which in this study included Transparency International-Kenya, donors like Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and related government agencies and their stakeholders involved in implementing ethics and anti-corruption policy and programs in the Kenyan public sector.

In constructing the social processes behind collaborative arrangements, organisational studies have mainly focused on trust attributes common in these platforming activities. With trustful relationships within these collaborative implementation arrangements, stakeholders find a voice to effectively assist with identifying the nature and scope of policy programs, policy saliency, and strategic collaborations (Chelagat et al., 2019) against, for example, corruption (Johnston, 2005). Collaborative arrangements also provide the resources needed by the existing or new implementation networks (Milward & Provan, 2006). The Kenyan case hardly paints a unique picture regarding these assertions, as will be demonstrated shortly. More specifically, this paper’s analytical approach builds on cognition and affect-based aspects of mutual trust between organisations (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; McAllister, 1995) and the subsets they may produce to describe (cause-effect relationships of collaborative processes) the complex contexts of inter-agency engagements in public administration. This allows a more measurable understanding of these social processes by locating the role of trust attributes in collaborative governance systems.

Dimensions of Mutual Trust and Collaborative Governance Typologies

Noting the conceptual complexity of mutual trust and its ambivalent measurement indicators, the cognition and affective trust components provide functional indicators for studying social processes and challenges in collaborative implementation arrangements. The cognition trust ‘refers to an evaluative belief and usually a certain extent of experience and knowledge about the other actor. Cognition-based trust is founded on evaluative predictions and calculations, such as the probability of the reciprocal behaviour of the other party’ (Pucetaite et al., 2010, p. 199).

Based on cognition-based trust, rational appraisals are contingent on performance, compliance, ethical behaviours, etc. Lewis and Weigert (1985) argue that under cognition-based trust, ‘we choose whom we will trust in which respects and under what circumstances, and we base the choice on what we take to be “good reasons,” constituting evidence of trustworthiness’ (p. 970). The trustees’ choice to trust or distrust is based on adequate knowledge or ignorance (McAllister, 1995). Other subsets of inter-organisational or mutual trust are, therefore, performance-based, integrity-based, and transparency-based trust (Schoorman et al., 2007). It can be traced to how values like integrity, accountability, and representation are coupled with functional organisational norms or culture.

Conversely, affective-based trust is a sentimental and emotional bond between individuals. Individuals invest emotionally in trusting relationships, genuine expressions, and care and concern for their partners’ welfare. Affective relations have been extensively studied in African politics and public administration (Hyden, 2006). It has been found to underpin relations between public administrators even when dealing with organisational wrongdoing (Onyango, 2017, 2023; Cheema et al., 2021). Also, in affective trust, there is a belief in the intrinsic virtue of such relationships and the reciprocity of such sentiments (McAllister, 1995, p. 26). This facet of trust takes stock of a relationship’s history over a long period. It may be needed to sustain long-term organisational development. This means organisational environments should feature value congruence between trustees, the fulfilment of expected outputs, sustained performance, and internal institutional culture (Pucetaite et al., 2010).

Most importantly, Pucetaite et al. (2010) contend that affect-based trust ‘is proactive: it involves a mutual expectation of fair and honest behaviour. It is also characterised by congruence between the parties' values and interests’ (p. 199). Therefore, it may stimulate other subsets, mainly trust-based, predictability-based, and credibility-based (Schmidt & Schreiber, 2019). Affect-based trust can also enhance strong and semi-strong trust forms (Barney & Hansen, 1994). While referencing Barney and Hansen (1994), Schmidt and Schreiber (2019) summarise the distinction between the two forms of trust in the following manner:

Semi-strong trust occurs when parties to an exchange are protected through various social and economic costs imposed by governance devices, while strong trust emerges despite governance mechanisms. Strong trust… depends on the values, principles and standards of behaviour internalised by parties. One could also argue whether it may be included in the definition of social governance. Moral and ethical behaviour, taken from an anthropological perspective, are evolutionary forms of exclusion of individual actors from the group (Schmidt & Schreiber, 2019, p. 74).

These contours of trust are more complementary in the public sector, where managing collaborative networks flourishes and often takes on vertical rather than horizontal management principles. At the same time, the former aspect may rely more on control or mandated principles (Maurya et al., 2023), and the latter, among others, chiefly factor in and front elements of trust like compliance and goodwill, equality, and confidence between partners (Milward & Provan, 2006). With these in mind, and since the multi-agency approach is conceptually ambiguous, it is often modelled under different categories or typologies, where each model is inclined towards achieving outcomes or purposes. These can be summarised in Table 1 below, articulating hierarchical, working mode, and engagement levels (Fox & Butler, 2004).

According to Fox and Butler (2004), under the levels of engagement typology, partners can be involved in mainly three functions: (a) strategic function, which focuses on the priorities that influence the strategic plans of the individual partner. This is explicit in public agencies like those in Kenya and elsewhere. For instance, Kenya’s Ethics Anti-Corruption Commission’s strategic plan (2018–2023) was drafted in collaboration with other stakeholders, mainly Transparency International (TI-Kenya) and other government agencies, like the Commission for Administrative Justice (CAJ) (World Bank. (n.d.). The same can be said of Kenya’s health policy programs (Chelagat et al., 2019); (b) commissioning deals with the commissioning priorities of individual partners, including performance management of the policy programs. An example is Kenya’s implementation of the current 18th-cycle performance contracting regarding anti-corruption strategies and policies in the public sector; (c) policy programs are another part of the levels of engagement collaborative model. It is concerned with transforming the individual partner from a virtual to a physical organisation that anyone can engage with. These, however, do not practically work in isolation from other models, that is, mode of working and hierarchical models, which deal with issues such as autonomy, specialisation, coordination, planning, legitimacy, communication, and information sharing. A closer look at the processes behind these outcomes and purposes shows the need for mutual trust in coupling legal collaboration parameters with essential social functions.

In the public sector, these typologies’ components can also be linked to Mary Parker Follet’s famous coordination principles in the context of a multi-agency network. These principles include the early stages principle that enables effective mapping of challenges such as limited resources, bounded rationality on decision-making, and efficient planning function mechanisms. The continuity principle may enhance certainty, learning, and seamlessness in public organisations’ decision-making and implementation. Despite being more descriptive of internal relationships between the supervisors and subordinates, direct contact as the third principle may strengthen inter-agency relationships.

Direct contact can enhance coordination through effective communication and reduced pathologies. It has become commonplace that pathologies like red tape and routines often stem from hierarchy and hinder building mutual respect and trust in a multi-agency network (Bardach, 1998). The fourth principle of reciprocal relations is a central dimension of this study because it can lead to mutual trust through openness and transparency within and between agencies in a multi-agency network (Milward & Provan, 2006). Altogether, these aspects of trust can be consolidated in the following analysis framework, taking on the institutional structure, culture, and external environment dimensions of public organisations.

Framework of Analysis: An Integrative Approach to Trust in Public Sector Collaborations

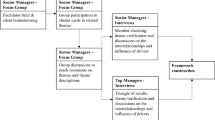

This paper’s threefold multi-agency approach of trust builds on the above broad aspects of mutual trust to model three broad areas or organisational dimensions, which cover (a) the structural features of public organisations or the rational-bureaucratic perspective, (b) the informal variables of public organisations or the cultural perspective, and (c) the broader ecological variables of public organisations or the environmental perspective, as illustrated in Fig. 1 below.

Rational-Bureaucratic (Normative) Perspective

The rational-bureaucratic systems order cognition-based trust between partner members. They stipulate the normative foundations of the bureaucracy that define formal relationships, the designs of organisations, and the degree of compliance with different roles and authorities in implementing policy programs. They further provide legal legitimacy for effective boundary-spanning strategies, which unpack legal complexities that may limit the leeway of action and technicalities hindering policy collaborations. The subsequent legalistic flexibilities and organisational culture are antecedents for internal and external trust-building efforts, which can alternatively enhance institutional capacity and personnel commitments and help determine the organisational purpose, clientele, and existing or possible collaboration strategies. Additionally, these rational systems involve organisational leaders’ initiatives or how they use them as instruments to influence organisational values, vision, policy designs, and problem structure norms.

In his study to map what he considers African management philosophy in Kenya and Tanzania, Mapunda (2013) shows that Kenyans and Tanzanian ‘employees expect the manager or leader to make authoritative decisions, to be decisive. In their minds, that is what he is employed to do. Consultation would be perceived as a sign of weakness – a lack of knowledge and confidence from the manager or leader. Teamwork and empowerment are associated with “Western” management styles’ (p. 14). While this may be applicable, it also suffices to state that organisational leaders’ actions take on different issues. This includes their personal characteristics, historical relations between employees, and the situation at hand. For instance, there are more possibilities for consultations between organisational leaders and senior members or employees within public sector collaborations. Another factor is the specific organisational culture and its mandate. These factors may determine how organisational leaders utilise their legal mandates in collaborative initiatives.

From a rational-bureaucratic system perspective, public managers considerably score high on rationality (Christensen et al., 2007) and engage in structural-instrumental legitimation of policy initiatives to improve internal and external environments for boundary-spanning activities. Jurisdictive responsibilities and functions bind institutional policy relationships for trust-building strategies. These functional roles may further enhance what Benne and Sheats (1948) call task roles. Task roles relate to the information and data-seeking efforts, initiating and clarifying ideas, proposals, plans, coordination of groups, and groups’ orientation towards achieving organisational goals and establishing outside contacts for policy collaboration and networks for integration processes.

Integration processes, in this case, are particularly critical in measuring the effectiveness of policy programs. This means the logic of action in rational-bureaucratic functions is that of consequences. Public managers weigh their actions on instrumental actions or bureaucratic scorecards and corresponding policy outcomes (March & Olsen, 2006; Christensen et al., 2007). Thus, building inter-agency trust strategies depends on existing instrumental capacities, the nature of public leadership, unambiguous objectives, and resources attached to policy programs, as I will show further in the data analysis and discussion sections below.

A Cultural Perspective

Cultural systems frequently form organisations’ main operational repertoires (Hampden-Turner & Trompenaars, 2008). As cultural systems, informal norms, values, and processes animate the interfaces between formal and informal administration properties. Overall, cultural systems connote composites of organisational culture, which closely match rational-bureaucratic components. For example, bureaucratic personalities of openness to learning from experiences and agreement align with the organisation’s performance orientation, promote team-building attitudes, and value integrity, innovations, etc. Studies have shown that cultural systems sustain and support collaborative networks (Bouckaert, 2012; Onyango, 2019a, 2019b). This is essential in retaining critical actors within an inter-agency collaboration, especially by enhancing organisational communication and commitment. In this respect, organisational culture is considered a strategy that can be harnessed and manipulated to improve organisational commitment and productivity. Consequently, managers are often advised to nurture and utilise culture to sustain performance and collaborative public management strategies.

The cultural perspective underscores the affect-based trust composites. It emphasises ‘internal aspects of institutionalised organisations, historical legacies, and established traditions but also looks at external institutionalised environments and prevailing beliefs regarding what constitutes relevant problems and good solutions’ (Christensen et al., 2007, p. 3). Therefore, unlike the bureaucratic system perspective, the logic of action from the cultural system perspective is that of appropriateness—where appropriate behaviours do not call for rational deliberations. Instead, the focus is on what is most likely applicable, tried in the past, or drawn from previous experiences and lessons that have worked elsewhere (Christensen et al., 2007, p. 3).

The logic of appropriate, in this case, may also entail behaviours primarily drawn on dominant norms and values taken for granted and have been perpetually practised or rationalised by administrators. Cultural imperatives also mean that integrity and efforts to enforce them in bureaucratic contexts have more to do with administrative personalities and relations than rules. This may partly explain how public agencies enter partnerships and why some of these partnerships may collapse or remain stable and sustainable, as will be explained further in this paper.

The Environmental Perspective

The environmental perspective integrates both the internal and external surroundings of an institution. Organisational environments, such as working conditions in the institution and management styles within and between government institutions, may result in some degree of trust or distrust between collaborating agencies and between these agencies and the citizens (Bouckaert, 2012). As such, contingencies, mainly political trust, public trust, and institutional trust towards the government or agencies concerned with realising a particular policy program, shape a typology for multi-agency relations and are critical in building inter-agency trust.

Moreover, employees’ internal environments are highly influenced by the prevailing management patterns and institutional trust levels, including collective mindsets (Ohemeng et al., 2019). This way, public leaders are tasked with changing mindsets from defensive to productive reasonings and creating new ways of managing the personnel to become innovative. This involves encouraging teamwork, effective conflict resolution mechanisms, and a climate of trust. The environment of trust ‘encourages risk-taking behaviours, such as cooperation, knowledge sharing and helping colleagues in need, because employees are confident their generosity will be reciprocated’ (Ohemeng et al., 2019, p. 3). This will produce different teamwork strategies and outward-looking performance definitions through collaborations and knowledge-sharing.

Ancona and Caldwell (1992) contend that team strategies in an organisation towards their environment can be categorised into informing, parading, and probing teams. ‘Informing teams remain relatively isolated from their environment; parading teams have high levels of passive observation of the environment, and probing teams actively engage outsiders. Probing teams revise their knowledge of the environment through external contact, seek outside feedback on their ideas, and promote their teams’ achievements within their organisation’ (p. 5). They further identified four typologies of boundary-spanning activities—ambassador, task coordinator, scout, and guard. The ambassador activity relies on the boundary spanner to access the organisation’s power structures. The task coordinator activity identifies how the personnel can access the workflow structures to manage horizontal dependence. Scout activity concerns the acquisition of pertinent ideas and information. The guard activity protects information from external parties (Curnin, 2016, p. 2). These are determined mainly by an individual organisation’s leadership style, knowledge transfer, and training, as well as internal ethical climate and managerial strategies.

In short, collaborative arrangements in the multi-agency approach to the implementation of programs seek to de-bureaucratise public policy and service-delivery processes. This should, among others, involve acquiring additional resources and skills that come with cooperating with like-minded organisations. Cooperation needs reciprocal relationships, matching values and norms, shared missions and vision, teamwork, communication flow, ethical management tools, and a positive attitude towards each other (Pucetaite et al., 2010). Additionally, collaborative arrangements call for confidence, transparency, openness, compliance, and information-sharing among partners. In other words, mutual trust between partnering agencies involved in implementing or delivering a particular policy program is critical and central for co-creating sustainable implementation strategies (Ansell et al., 2022).

Most importantly, mutual trust takes critical cues from contextual variables or local dynamics underpinned primarily by social processes and experiences (Le & Nguyen, 2023; Stys et al., 2022). In public administration, these will include a complex mix of sociocultural, economic, and political norms and structures that often explain trust deficits in transitional economies. According to Pucetaite et al. (2010), trust deficits in public institutions in the global South stem from.

[…] certain social-historical processes that [condition] lower self-regulation, authoritarian and patriarchal organisational structures and lack of partnership-based interrelations between the manager and employees, a rather flexible attitude to the norms and standards, negligent behaviour at work, etc. (p. 198).

In a study looking into the impact of leadership training programs on knowledge transfer to improve healthcare systems in county governments in Kenya, it was established that successful experiences were because of the ‘training design, work environment climate, trainee characteristics, team-based coaching and leveraging on occurring opportunities’ (Chelagat et al., 2019, p. 1). Conversely, programs failed because of the need for more effective communication, longitudinal coaching, and work-team recruitment (Chelagat et al., 2019). This paper framework’s threefold approach shows that creating trustful relationships is stimulated when bureaucratic, cultural, and environmental rationalities are closely matched.

Public Sector Collaborations in Kenya: A Contextual Review

Mandated and organisation-specific innovations in public sector collaborations are becoming fashionable in Kenyan public administration, as government agencies and public managers align their systems and interests with today’s public governance principles hoisted in Vision 2030. Like elsewhere globally, studies in Kenya, such as those by Bernardi and De Chiara (2011), show that functional monitoring systems of policy programs like those dealing with HIV/AIDS have worked better when agencies concerned collaboratively undertake them. Collaborative arrangements in Kenya have taken some of the following dimensions: (a) collaborations with international organisations (or donor agencies); (b) collaborations with locally based non-governmental organisations and civil society groups; (c) collaborations between regional governments or inter-governmental partnerships (i.e., economic blocs); (d) collaborations between government institutions and community associations/groups like in the context of communal resource mobilisation, e.g., through youth or women groups; and (e) collaborations between government institutions themselves.

However, these distinctions are not clear in practice and sometimes need to be refined. They may overlap or include other streams, such as layers of inter-agency relations and membership from non-governmental organisations, as commonplace in Kenya. The last stream, or collaboration among government agencies, is increasingly becoming the implementation model for policy programs, especially in the national bureaucracy and between county governments and national institutions (Otenyo, 2021). These arrangements aim to enhance the effectiveness of policy implementation. For example, the National Council of Administration of Justice (NCAJ), formed in 2011, is a high-level policymaking, performance, and oversight coordinating mechanism. Its membership comprises state and non-state justice sector actors. It is formally required to hold at least four council meetings per year.

The Chief Justice chairs NCAJ through a statute that seeks to institutionalise the council’s resolutions and policies in the public sector, including members such as the Law Society of Kenya, Kenya Prisons, Directorate of Public Prosecutions, the Directorate of Criminal Investigation, and Inspector of Police, among other members of mutual interest. Members have lauded NCAJ for ensuring enhanced policy development and effective collective action on policy implementation and evaluation. For example, with the outbreak of COVID-19, it convened several times to draft guidelines that would cushion the spread of COVID-19, mainly in prisons and other areas.

The role of donor agencies as funders in initiating or sustaining these networks has also been extensively documented in Kenya. Following massive food shortages and malnutrition in the 1980s, donor agencies such as the European Union (EU) and USAID worked with the government to resolve Kenya’s disastrous food security (Otenyo, 2021). For example, within the Kenyan National Plan of Action (2013–2017) framework, the Better Migration Management (BMM) Program, a cross-national collaborative framework, has been legitimated. BMM is funded by the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa and the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). BMM has been critical in training. It has also been the source of information for the Ministry of Immigration, Kenya Police Service and Department of Children, and other stakeholders dealing with combating human trafficking. This is mainly through Isiolo County for Eritreans and Ethiopians en route to South Africa because of human trafficking and the smuggling of migrants between the two countries.

Other multi-stakeholder arrangements include the Uwiano Platform for Peace, whose membership comprises UNDP, UNWomen, Kenya’s National Security Council (NSC), the National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC), IEBC, and PeaceNet, which has a presence in all the 47 counties or local governments in Kenya. Besides being critical in training government and non-governmental personnel, this platform has enhanced coordination among its partners at national and sub-national levels. In the context of anti-corruption policy programs, administrative executives at all government levels are engaged in different multi-agency arrangements. These are created through statutes (rational-legal systems) or personal initiatives (informal boundary-spanning activities) to enhance the effectiveness of corresponding statutes. This has been motivated to address the complex problem of public policies and create an environment for the comprehensive implementation of cross-cutting policy programs.

In their study of the Kenya Inter-Agency Rapid Assessment Mechanism (KIRA), Limbu et al. (2015) show that KIRA resulted from the need to enhance intellectual capital in addressing the humanitarian crisis in Kenya. They mention that ‘UNICEF Kenya with UNOCHA East Africa, Assessment Capacities Project, RedR UK, Kenya Red Cross and the Kenyan Government put in place the partnership-based collaborative Kenya Inter-Agency Rapid Assessment (KIRA) and established a mechanism capable of conducting a multi-agency, multi-sectoral assessment of humanitarian needs’ (p. 59). However, this does not happen without constraints like power, transparency issues, and organisational sovereignty politics, in which institutions have often overcome through strengthening social or informal networks. Challenges like overlapping organisational mandates, political inclinations of actors, capacity issues, the lack of joint budgeting, assessing collaborative capacity, and trust-building from principled conduct have also been highlighted (these have also been confirmed elsewhere and outside Kenya, e.g., Hudson et al., 1999; Percy-Smith, 2006; Milward & Provan, 2006; Onyango & Ondiek, 2021).

To address these deficits, collaborative governance theorists have thought that policymakers and governance practitioners involved in such arrangements should be keen on building mutual trust to overcome institutional constraints of inter-agency collaborations (Stoker, 2006). Studies in Kenya like Zainal and Cahyadi (2023) confirm this by showing how mutual trust or social understanding between partners should reduce the above collaborative restrictions to increase the program’s performance.

Another study on designs for implementing HIV/AIDS in Kenya found that policy actors adopted a multi-agency approach because ‘the fragmentation of externalities has been producing less bureaucratic quality and capabilities, deriving from a significant lack of coordination and generating a proliferation of projects and creation of parallel systems of monitoring and evaluation’ (Bernardi & de Chiara, 2011, p. 35). In this line of thought, Chelagat et al.’s (2019) study on collaborative approaches to implementing health policy programs in Kenya established that contextual variables may inform challenges to adequate collaborative arrangements.

In their findings, they note that for the trained managers to utilise the learnt knowledge and skills optimally, ‘“the following contextual constraints should be addressed: (i) inadequate management support in the provision of necessary resources for implementation, (ii) inadequate team and staff support, (iii) high staff turnover, (iv) misalignment of board’s verses manager’s priorities, (v) lack of technical expertise required to implement the projects, (vi) endemic strikes, (vii) negative politics and (viii) poor communication management’ (p. 11).

This means that much as multi-agency networks also need appropriately designed rational systems to be effective, they are primarily based on public managers’ boundary-spanning skills that come with nurturing social networks or translating them into an organisational resource (Raudeliūnienė et al., 2016). Several studies on collaborative governance generally show that to do this, managers need to trust one another in these arrangements (Stoker, 2006; Oomsels & Bouckaert, 2014; Getha-Taylor et al., 2019; Christensen & Lægreid, 2019; Ran & Qi, 2019; Onyango, 2019a, 2019b). In public administration, the public value and governance theories vividly discuss the role of trust in discerning how multi-agency collaboration functions (Temby et al., 2017; Song et al., 2022). They have shown a significant correlation between trust and collaborative arrangements, where trust is needed for the personnel to be more motivated by engaging in networks, partnerships, mutual respect, and learning relationships. These networks and the challenges underpinning them are evident in Kenya’s ethics and anti-corruption policy, as described further below.

Kenya’s Ethics and Anti-Corruption Policy and Collaborative Implementation Arrangements

The Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission (EACC) is the lead agency that coordinates anti-corruption policy strategies in government institutions, commissions, and authorities. This has involved system analysis of public organisations to test their corruption loopholes. This involves partnering with these agencies by devising and engaging in different typologies or forms of multi-agency networks. Before the sessional paper No. 2 of 2018, which rolled out the National Ethics and Anti-Corruption Policy (NEACP), anti-corruption programs in Kenya were hosted in many legal frameworks, ethical guidelines, and other legislation to foster public accountability or strengthen public administration integrity systems. These include the Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act, 2003; the Bribery Act, 2016; Public Officer Ethics Act, 2003 (POEA); the Leadership and Integrity Act, 2012 (LIA); and the Public Finance Management Act, 2012. NEACP’s development and implementation take a collaborative governance approach effort by key government agencies like the Witness Protection Agency and Commission for Administrative Justice (CAJ). Cross-institutional synergies are highly recommended to realise the effective implementation of the policy (Republic of Kenya, 2020).

Based on the recognition that enforcement of this anti-corruption legislation and programs is cross-cutting and requires a multi-sector approach to be effective (an integrated policy), the National Anti-Corruption Campaign Steering Committee (NACCSC) and EACC have engaged in broad-based stakeholder consultations and networks. Partnerships and collaboration in anti-corruption efforts involve commissions, ministries, donor organisations, and other stakeholders. EACC has primarily partnered with agencies whose core business matches its own but is slightly different because of the complex nature of corruption as a policy problem. These include the Ombudsman’s office (Commission for Administrative Justice—CAJ) and the police.

Among other networks, through the Kenya Leadership and Integrity Forum (KLIF), EACC, CAJ, government ministries and their departments, and the Judiciary cooperate to enhance internal or vertical and external or horizontal coordination. This is on specific investigations and penalties that may emerge during the implementation of the Public Service Integrity Program (PSIP) strategies that were applied before the NEACP. As a component of the Civil Service Reform Programme (CSRP) reforms, anti-corruption policy programs were to be integrated into political-administrative structures through the PSIP framework. The PSIP was rationalised by matching public sector reforms with needed behavioural changes for a responsive, responsible, and accountable public administration. Therefore, training on integrity matters is critical to changing the culture and environments of administration. Consequently, PSIP requirements, mainly performance contracting (PC), would be integrated into all government agencies’ administrative systems.

The indicators for organisational performance are established within the PC to include the following strategies for integrating anti-corruption policy programs in the public sector: (i) developing anti-corruption policies. This should include a statement on managerial responsibility and the subordinate staff’s responsibility to address corruption in the institutions. Besides, a summary should point out potential corrupt practices and requirements like (i) developing institutional anti-corruption policies and creating corrupt prevention committees (CPCs) in partnering institutions. (ii) Realisation of corruption prevention committees or CPCs. This was to coordinate PSIP in the concerned agency and sensitisation through corruption campaigns within institutional jurisdictions.

There should also be an institutional review, monitoring, and evaluation of PSIP’s impact, including preparing and submitting periodical reports on the internal corruption status. (iii) Public entities should develop a corruption prevention plan (CPP). This includes developing risk management strategies and identifying critical functions and responses to risk areas. (iv) Institutions should develop specific codes of conduct according to the national ethical guidelines. (v) There should be frequent integrity training, including the appointments and training of the Integrity Assurance Officers (IAOs). The IAOs should provide technical support to the management on policy integration and conduct sensitisation workshops in collaboration with EACC.

Several multi-agency networks are meant to help integrate anti-corruption policy programs in Kenya to achieve these policy objectives. The public sector’s primary partnership networks are KLIF and the Integrated Public Complaints Referral Mechanism (IPCRM).Footnote 1 EACC defines KLIF as ‘a national integrity system to coordinate a unified sector-based strategy for preventing and combating corruption by forging alliances and partnerships with sectors across the Kenyan society’ (EACC, 2015, 37). KLIF has 14 members across the public and private sectors. These include legislature, Judiciary, executive, EACC, enforcement agencies, watchdog agencies, education, county governments, civil society, private sector, media, professional bodies, labor, religious sector, and constitutional commissions (refer to EACC website).

Under the KLIF umbrella, the EACC coordinated and rolled out a 5-year multi-sector integrity strategy dubbed the Kenya Integrity Plan (KIP). Through KIP, a roadmap was formulated ‘for all the KLIF sectors to implement a unified strategy to combat Kenya’s corruption. All the sectors and the respective institutions implementing the KIP align their anti-corruption interventions to the KIP and develop annual action plans and progress implementation reports’.Footnote 2

These reports provide an opportunity to assess performance and measure the impact of stakeholders’ anti-corruption activities. Furthermore, the IPCRM was formed in 2013 as a multi-agency information management of corruption reports among six partners. Membership includes the EACC, the CAJ, Transparency International (TI-Kenya) as the only non-governmental organisation partner, the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission, and the National Anti-Corruption Campaign Steering Committee. The National Cohesion and Integration Commission (NCIC) describes IPCRM as an initiative of five agencies. IPCRM aims to strengthen partnerships between the state oversight institutions in handling, managing, and disposing of the received complaints/reports. It should also give feedback to the members of the public who lodged complaints (NCIC, 2015, p. 35).

More reports on human rights, corruption, and hate speech, among others, have been reported by member organisations. For example, the IPCRM initiative ‘led to efficient and effective access of services at devolved levels by establishing one-stop complaints and referral centres that have enhanced access, especially in rural/remote areas, to public complaints procedures established to address hate speech and ethnic discrimination’ (NCIC, 2015, p. 36). The IPCRM ensures coordination, information-sharing, and building an inclusive approach to tackling corruption among its stakeholders. Thus, the integration of PSIP is partially conducted within a principal-agent framework and polycentric systems in the public sector. For example, in subnational public administration, the County Public Service Boards and Accounting Officers/Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) oversee the integration of the PSIP in collaboration with EACC and other commissions. The next section presents this study’s methodology.

Materials and Methods

This study examined the social processes behind challenges confronted by collaborative arrangements. These social aspects were constructed around mutual trust constructs, looking into how they underpin challenges that may accrue in understanding the effectiveness of realising integrated policies like Kenya’s ethics and anti-corruption policy. The explanatory variable was mutual trust. This investigated the agency of institutions and their personnel’s commitment toward realising integrated approaches in anti-corruption policy implementation. Inter-agency relationships within the lenses of inter-agency or mutual trust were defined as ‘the extent to which organisational members have a collectively held trust orientation toward a partner firm’ (Huff & Kelley, 2003, p. 82). Among other things, the inter-agency trust involved (a) reciprocity and mutualism (or interdependence) among partners; (b) commitment or moral obligation to the collective objective; (c) relative value congruence; (d) productivity, professionalism, and performance; (e) compliance, subjective evaluation either based on sentimental or rational judgements; and (d) openness or transparency, etc.

The same features have also been fundamental in evaluating the effectiveness of a multi-agency approach in the service delivery or implementation of policy programs (Hudson et al., 1999). The foci of mutual trust underscore trust-building strategies and trust-motivated engagements in multi-agency relations critical to effectively implementing anti-corruption policies as a public accountability composite. The dependent variable was the integration of anti-corruption policies in the Kenyan public sector. Multi-agency structures as forms of network respond to deficits arising from the traditional ways of managing public organisations. Pirson and Turnbull (2011) state that more hierarchical, larger, and more complex organisations like public institutions risk failures because of increased biases, errors, and missing data in communication and control systems, something that recent reports by the Office of Auditor General have established in Kenyan public procurement processes (Republic of Kenya, 2022). These problems introduce information overload to senior managers and respective regulators, which should be addressed by employing network governance. The latter ‘introduces a division of power via multiple boards, checks and balances, and active stakeholder’ (Pirson & Turnbull, 2011, p. 101). In addition, because composites of trust in public organisations take stock of the broader operational contexts of these agencies, conceptualising inter-institutional trust considers the three key features: bureaucratic structures, cultural or natural systems, and environmental variables (Scott & Davis [2007] 2015).

Data Sources and Analysis

This study was based on a descriptive case study strategy and data collection methods of secondary data. This involved documentary analysis of audited documents, periodical studies, and annual statutory reports by KLIF members. The KLIF members include EACC, the Ombudsman, Transparency International-Kenya (TI-Kenya), speech, and newspaper reports. The systematic analysis of these documents hinged on the main question, which sought to understand how challenges associated with multi-agency or public sector collaborations are influenced by and related to deficits of social processes of these arrangements as underpinned by mutual trust. The search or inclusion criteria focused on reports on challenges with keywords like resource allocation, information sharing, institutional partnerships and cooperation, governance structures, personnel training on integrity, policy on partnerships, and public sector collaborations for public accountability and anti-corruption efforts. The quality of these studies was appraised based on their explicit methodologies and cross-referencing of valid studies and statutory reports. Documents analysed included EACC’s (2018–2023) EACC annual report (2019/20) on partnerships and networks and the Commission of Administrative Justice (CAJ)’s (2019–2023) Strategic Plans; CAJ study reports on Counties (2014/2015) and Auditor General government fund report 2022, EACC quarter reports 2023, and Transparency International-Kenya briefs and reports, as captured in Table 2 below. The analysis was carried out continuously and further considered newspaper articles (mainly Business Daily) and studies by Transparency International-Kenya and World Bank, which touched on issues relating to collaborative arrangements within KLIF members such as the Director of Public Prosecutions, CAJ, and police.

Data analysis triangulated narrative, discourse, and content analysis of documents and existing qualitative studies mentioned above by EACC, CAJ, and Auditor General with newspaper reports. Data were thematically organised and tied to specific dimensions and referents of mutual trust as a social aspect of collaborative arrangements. These are cohesiveness, information sharing, performance, capacity-building, joint awareness creation, knowledge of EACC’s anti-corruption strategies, political interference, and interactions between EACC personnel and administrators in the studied counties. The discussion of the findings is analysed in light of trust referents.

Analysis and Findings

Employee Withdrawal and Leadership Deficiencies Among Different Agencies

In a study on corruption and unethical conduct in the health sector projects, EACC established that:

About half of the respondents were not aware of whether anti-corruption measures existed to ensure the integrity of contractors and monitor the implementation of healthcare projects. Majority of health staff were not aware whether counties or national health facilities sought authorization from the Controller of Budget before paying contractors for projects undertaken. Most of health staff interviewed were aware about the existence of the anticorruption measures (EACC, 2023, p. 86).

These findings demonstrate deficiencies regarding institutional and personnel commitments in collaborative arrangements to implement anti-corruption in Kenya. This may mean that reliability, competence, and confidence as referents of trust are hardly inherent in how anti-corruption collaborative arrangements are designed and implemented in Kenya. In other words, public leaders may have challenges deciphering and contextualising values of equality and commitment to realise reliability and related trust referents in a joint action arrangement for anti-corruption in the Kenyan public sector. Thus, there are deficiencies in creating and realising internal and external anticipations of collaborations to deliver better goals and make a difference that can nurture the collaborative relationship.

Public sector leadership must enhance and nurture the personnel’s support in member organisations to create a shared memory and reference points necessary to avoid goal ambiguities in KLIF and other multi-agency collaborations like IPCRM and, most importantly, the leadership to coordinate collaborative activities and effectively share information. From the above excerpts, the institutionalisation of these networks, that is, their routinisation and normalisation in organisational action in government institutions, rarely or insufficiently facilitates the required training, especially among the lower cadre and middle-ranking administrators.

For example, loopholes remain when it comes to system reviews to determine how PC requirements are mainstreamed into administrative systems at the county level. These loopholes have become increasingly conspicuous as KLIF members interact and find ways to seal them off. One way of dealing with this has been the adoption of technological platforms to reduce merging institutional fragmentations and overlapping incompetence in KLIF and complaints reporting collaborations through IPCRM. This can be further illustrated by the current chief justice’s explanation concerning what the Judiciary has done:

Recently, the Judiciary, in collaboration with EACC, launched a systems review of the institution’s policies, procedures and practices. This exercise is meant to streamline the systems in the Judiciary and result in sealing any systemic loopholes that facilitate corruption in the Judiciary. Automation is a key pillar for the Judiciary, with E-Filing being adopted in all courts countrywide. Automation is expected to eliminate the physical manipulation of files at the registry and safeguard the integrity of the institution. Further, the Judiciary has adopted cashless transactions in all courts countrywide to enhance transparency and accountability to minimise incidents of corruption. Court fees, fines and bail are paid and refunded through the M-Pesa mobile platform or the bank (TI-Kenya, 2021).

While this technological tool may be a good direction, technology comes with underlying dysfunctions. Some studies have shown that Kenyan administrators generally have lethargic attitudes towards technology platforms in the public sector (Bakibinga et al., 2020; Onyango & Ondiek, 2021). Leveraging technological platforms to reduce institutional fragmentations or ensure effective inter-agency collaborations requires institutions to be well-equipped with appropriate facilities. But these need to be improved in Kenya, besides dealing with the need for extra funding to sensitise administrators and citizens on how these technologies work. This adds to the fact that access to the internet may be a limiting factor because it may be expensive for a section of the population and unavailable in most parts of the country, especially in remote areas. Coordinating multi-agency arrangements at the local government levels is a challenge in implementing anti-corruption policies in the public sector.

Besides, there are no clear incentive strategies to create an environment where the administrative personnel would improve their competence by complying with organisational responsibilities or commitments to ethics and collaborative requirements for anti-corruption policy programs. In this light, trust between civil servants, employees, and their managers can direct the credibility of administrative actions (see Ohemeng et al., 2019, who provide similar insights from the Ghanaian civil service). From this, it becomes clear that institutional fragmentation and overlapping competence may stem from reliability and confidence-based trust deficits within and between KLIF members, mainly the oversight commissions. Furthermore, to cite Bulińska-Stangrecka and Iddagoda (2020, p. 11), employees in oversight and mainstream public institutions in Kenya could be described as ‘sleepwalking through their workday, putting time but not energy or passion into their work.’ This most significantly concerns activities promoting policy program integration within government agencies’ legal rational systems.

In other words, most administrators and management are more isolated or withdrawn from external environments (informing teams) or horizontal coordination mechanisms with little exposure to the structures and functions of the existing multi-agency networks for anti-corruption policy programs. The result is a fluid relationship between ethical behaviour and ethics management tools. It has been argued that organisations must go beyond mere adoption at the core of these two dimensions to ensure that employees are conversant and skillfully interpret, manipulate, and appositely apply or integrate the policy programs. This would enhance the performance-based trust that eases other typologies of relations beyond hierarchical to more cultural or informal and environmental orientations.

Thus, the levels of organisational performance or the performance-based and credibility-based trust in EACC to enforce public integrity corresponded with and prioritised the outcomes of institutional contexts of anti-corruption policy programs in public administration. Moreover, there is horizontal inequality in knowledge dissemination and information on anti-corruption policy programs within public organisations. Some units and departments are more knowledgeable about the existing structures to integrate anti-corruption programs in the public sector than others. This is mainly attributed to two factors. First is the leadership styles that relatively differ from one institutional context to another. Leadership style in member organisations influences the collaborative environment and internal inclinations corresponding to levels of awareness of multi-agency platforms. These may affect confidence, information-sharing, and organisational commitment. A critical issue also concerns the ownership of shared information, that is, whether decisions and reports on institutional progress are participatory at all levels, internally and externally, between PSIP and KLIF members. In other words, clear guidelines and designs concerning information sharing must be established, leading to coordination and commitment dysfunctionalities.

Two, the interactions between bureaucratic hierarchy and leadership patterns also lead to a preference for inward-looking strategies or pessimistic approaches to multi-agency networks in the Kenyan public sector. This may mean trust levels are low among the agencies concerned, which can be attributed to the slow mainstreaming effort of anti-corruption policy programs in the public sector. Consequently, instead of being highly integrated, the multi-agency networks in Kenya for anti-corruption policy programs can be described as ‘looser, less stable in membership and [have] weaker points of entry’ (Hudson et al., 1999, p. 243). It is, therefore, not surprising that little trust exists among partnering agencies attendant to, among others, the institutional members’ closed orientation on handling corrupt practices within their own ranks.

The Unclear Governance Structure, Weaknesses of Coordination, and Inter-Agency Conflicts

In a report by a working group under the National Council for the Administration of Justice (NCAJ) on land issues, submitted in July 2014, it was indicated that ‘weak legal and administrative frameworks for professionals dealing with land, inadequate resourcing, limited knowledge and accessibility of regulatory frameworks, missing data and poor state of land registries among others’ (CAJ, 2014, p. 94) were some of the emerging issues that affected land ministry. In response to such issues, NCAJ and KLIF member agencies have conducted personnel training and several successful investigations. This has, among others, resulted in asset recoveries worth millions of dollars in collaboration with ministries, directorates, and other regional agencies in East Africa (EACC, April 2019 report). In so doing, collaborative efforts helped EACC and CAJ with capacity building and knowledge transfer, as shown in the excerpts from EACC’s most recent report summary (2019/2020).

The Commission remains committed to partnering with national, regional and international players in the fight against corruption and unethical conduct. This year, the Commission benefited from technical support in the areas of financial investigation and skills development from the United Nations Office on Drugs & Crime (UNODC), the National Crime Agency (NCA) and the United Kingdom Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the United States Department of Homeland Security Investigation (HSI), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and other partners. At the National level, the Commission engaged stakeholders through the Kenya Leadership Integrity Forum (KLIF), the Multi-Agency Team (MAT) and the Referral Partners Platform (EACC, 2021, xv).

However, these efforts may have been increased by negative attitudes and perceptions of distrust around KLIF that are generally based on transparency problems in almost all partnering oversight agencies. This is also similar in mainstream government institutions. Further, most oversight institutions, like other partners, need more effective communication mechanisms and moral authority to lead the integration of anti-corruption policy programs in public administration. Thus, aspects of cognition-based or performance-based trust were displayed concerning the role of EACC, particularly in multi-agency networks. EACC, like other oversight institutions, is faulted or distrusted in some quarters because of its public record of underperformance and the need for more transparency within its ranks.

Trust literature ideally describes all three subsets of cognition and affective-based trust, mainly behavioural-based, competence-based, and integrity-based. It was mentioned that IPCRM is derailed because of most commissions’ prevailing low legitimacy concerns (trust-deficit problems). For instance, GIZ had to stop funding IPCRM because most public leaders, especially from the commissions, stopped attending meetings and referring cases outside their mandates to other partners.

The result could be that individual organisations’ institutional designs constrain multi-agency relations functions. As the Kenyan case established, this may mean that the persisting inter-agency conflicts common in public sector networks may stem from bureaucratisation deficits and lack of institutionalisation of the multi-agency arrangements. For instance, in its 2019/20 report, CAJ mentioned that some of the challenges it experiences include unresponsiveness by public institutions, which hinders the timely resolution of complaints on wrongdoing. There is also an insufficient legal framework relating to the enforcement of decisions and recommendations of the commission and regulatory framework for access to information (CAJ, 2021, P. 97; Onyango, 2021).

Unresponsiveness reflected claims of sovereignty or autonomy by partners, leading to tugs of war within these networks in the implementation of anti-corruption programs. These challenges are characteristic of deficits in different agencies’ structural designs and environmental and cultural composites. This way, trust-building strategies are frustrated by a complex mix of structural designs and cultural and environmental factors. For example, environmental issues relating to variance in resource endowment among KLIF members determine the degree of engagement by their respective management to related anti-corruption activities. Limited funds are related to some levels of withdrawal and reactive involvement in KLIF operations. This is also attributable to the KLIF network’s typology, which comes out more as a legal obligation to some members than a voluntary membership.

The most real unintended consequence of multi-agency networks amidst explicit failures may be their ability to initiate and support local capacity-building processes that underscore learning and resource mobilisation, either in skills, financial gains, or information. For instance, in its 2019/2020 report, EACC realised several failures based mainly on capacity-related dysfunctions. In the Ministry of Information, Communications and Technology, the report uncovered several dysfunctions, primarily:

[The] inadequate number of suppliers accredited by the ICT Authority to supply some categories of ICT items. Failure to undertake [a] post-accreditation assessment to ascertain compliance with the expected standards by accredited suppliers (EACC, 2021, 50).

These capacity-related issues threaten KLIF and other multi-agency arrangements to improve public accountability, showing that legal-rational systems, like other dimensions, can hardly work in isolation. Indeed, apart from the multi-agency approach for anti-corruption programs, similar challenges have been explicitly displayed in disaster policy management programs, mainly in the ‘war on terror’ worldwide. As a policy framework in Kenya, multi-agency networks through the National CVE-Strategy (National Strategy to Counter Violent Extremism) and the Usalama Platform have been heavily supported by actors inside and outside the country. Besides, advocacy coalitions support organisational policy-oriented learning, including equipment support to Kenya’s anti-terrorism police units and community policing. Also, in the public sector, EACC reported in its 2019/20 (2021) that it ‘undertook capacity building workshops for 220 newly appointed County Public Service Board (CPSB) Members drawn from 41 boards to implement Chapter 6 effectively. In addition, the Commission undertook capacity building in 26 public institutions to equip them to effectively implement the law on declaration of income, assets and liabilities’ (EACC, 2021, P. 63). In short, multi-agency approaches that are adequately anchored on social cohesion between actors can result in unorthodox successes or gains in practically hostile environments for institutional performance.

The Professionality and Competing Organisational Interests—Integrity, Credibility, and Trust

Besides the lack of a more information-sharing culture and loose structures between KLIF partners, there were notable deficiencies regarding transparency, integrity, and confidence among collaborative actors. This is principally a result of the prevalence of unethical culture within member organisations. For example, inter-agency investigative reports on corrupt activities within KLIF members, like in a case in 2015 when CAJ investigations and the Auditor General reported corruption within EACC’s ranks, the EACC refuted the issues. KLIF’s legal lacuna is featured in this case, as shown below.

[….] the EACC director for legal services later wrote to the Ombudsman urging him to respect and uphold the rule of law given that the matter in question was being handled by the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI). ‘The matters which you intend to investigate are now within the purview of another law enforcement agency (DCI). Section 30 of the CAJ Act states that the Commission shall not investigate any matter for the time being under investigation by any other person or Commission established under the Constitution or any other written law,’ the letter said (Business Daily; February 18, 2015).

To control access to information on corruption claims within its ranks, EACC adopted a rigorous approach to discourage internal cooperation by its personnel with CAJ investigators (Business Daily, February 18, 2015). This points to the mismatch between bureaucratic structure, culture, and environmental inclinations that come with collaborative arrangements. In particular, the then EACC management resorted to an autocratic leadership style that arguably exhibited underlying problems in employee-manager relations. Most importantly, internal inter-agency trust contexts may have demonstrated personnel distrust towards some partners, indicating confidence problems and performance deficits by commissions. This could have also signalled little or inadequate social cohesion and recognition to collaborate or commit to KLIF and IPCRM by local government units.

Public institutions and oversight agencies are more concerned with carrying out their core mandates over pursuing collaborative expectations contained in the various partnerships they are involved in—the member-only inclinations of some partnerships considered integrating policy programs within the multi-agency and network frameworks. In fact, given the challenges with poor resource allocation, underlying inter-agency differences, and issues bordering on political legitimacy, the commissions abandoned committing to KLIF and IPCRM networks. In short, integrating ethical tools is threatened because commitment to multi-agency arrangements needs to be more substantiated by members’ concerns with carrying out their core business.

From this, internal problems with organisational coherence resulting in insufficient commitment and fluid relationships between the management and the employees concerning ethical management tools may weaken the effectiveness of multi-agency arrangements. The internal incongruence of member organisations is also attributed to the complexity of membership within KLIF and IPCRM networks while conversely aggravating sovereignty claims among partners. This would also imply higher engagement levels than the mode of the working type of multi-agency activities for anti-corruption programs in Kenya.

Internal organisational integrity problems may create cognition-based trust deficits and constrain Kenya’s multi-agency networks for anti-corruption programs. More importantly, inter-agency conflicts produce inward-looking implementation strategies over collective methods for policy programs by member organisations. Such normative deficits constrain trust-building initiatives in joint action contexts, mainly in organisational commitment, communication, and information-sharing.

The case in point can be seen in a study by the World Bank on a multi-agency approach to implementing anti-corruption policies in Kenya. This study stated that key administrative challenges reside in the prevailing administrative skillsets and culture. It mentions that ‘traditionally, the obstacles to coordination between government agencies [in Kenya] stem from fundamental cultural differences and motivations of different agencies’ (World Bank. (n.d.), p. 268). These findings align with studies elsewhere (Song et al., 2022; Percy-Smith, 2006), showing that multi-agency networks rely profoundly on partnering organisations’ cultural and environmental systems or contexts. These dimensions indicate potential linkages between organisational performance deficits in multi-agency relations and trust variables (O'Toole, 1997). The public sector’s pyramidal or hierarchical organisational forms and implementation guidelines take on top-down synergies. In other words, the hierarchy or public leadership has been said to play a vital role in cultivating trust among employees and between the institution and its stakeholders (Zhou & Dai, 2023; Zarychta & Wong, 2024; World Bank n.d.).

Even so, hierarchical interventions may struggle with developing and perfecting outward-looking collaborative strategies, especially in politically sensitive public agencies. As such, collaborative interventions in public administration have higher affinities towards pursuing inward-looking strategies that may eventually constrain trust-building processes between institutional actors (Onyango, 2019a, 2019b). This way, despite their essence in driving collaborative governance arrangements, the bureaucratic power connotations of hierarchies may also reduce the human face and relations needed for effectively realising administrative or implementation processes. This is especially so regarding where public managers are engaged in collaborations, like in Kenya (also see Mu & Cui, 2023, concerning the Chinese experience).

Conclusions

Institutions are social entities and actors that flourish when their social processes are nurtured. The nurturing, here, should ensure that organisational objectives are envisioned on the organisational structures and should be coupled with organisational culture and values external to the organisation (environmental aspects). For practice, this study’s findings show the need for public innovations that may enhance or cultivate social aspects (mainly) of collaborative arrangements in the public sector. It further indicates the need to deepen cultural and environmental composites for a multi-agency to work (Bardach, 2001). Governments need to devise more innovative tools to measure their effectiveness beyond the legal bureaucratic principles to track or evaluate the progress of a multi-agency network. This was one of the challenges experienced in evaluating the integration of Kenya’s PSIP framework.

The integration of PSIP was heavily latched on to rule-based tools or rational principles. This rule-based orientation inevitably overlooks nurturing established and functional social or informal innovations because they rarely underscore structural adjustments to foster public administration innovations (Kim et al., 2004). In retrospect, there is a high likelihood of little change in the ethical climate in public administration needed to build trust in a multi-agency approach to anti-corruption policy programs. This would also mean that multi-agency approaches would remain more reactive than proactive in environments where the unethical climate is the primary source of normative deficits. Public organisations must go beyond their normative foundations or rational-bureaucratic aspects to recognise, harness, and privilege social functions in their collaborative actions to improve effectiveness and coordinate integrated policies like Kenya’s ethics and anti-corruption policy.