Abstract

Underserved patients face substantial barriers to receiving cancer genetic services. The Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM) study evaluated ways to increase access to genetic testing for individuals in underserved populations at risk for hereditary cancer syndromes (HCS). Here, we report the successful implementation of CHARM in a low-resource environment and the development of sustainable processes to continue genetic risk assessment in this setting. The research team involved key clinical personnel and patient advisors at Denver Health to provide input on study methods and materials. Through iterative and collaborative stakeholder engagement, the team identified barriers and developed solutions that would both facilitate participation in CHARM and be feasible to implement and sustain long term in clinical care. With a focus on infrastructure building, educational modules were developed to increase awareness among referring providers, and standard methods of identifying and managing HCS patients were implemented in the electronic medical record. Three hundred sixty-four DH patients successfully completed the risk assessment tool within the study, and we observed a sustained increase in referrals to genetics for HCS (from 179 in 2017 to 427 in 2021 post-intervention). Implementation of the CHARM study at a low-resourced safety net health system resulted in sustainable improvements in access to cancer genetic risk assessment and services that continue even after the study ended.

Trial registration NCT03426878

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Underserved and marginalized populations experience substantial barriers to receiving cancer genetic services and care (McCarthy et al. 2016, Shields, Burke and Levy 2008, Cragun et al. 2017, Meyer et al. 2010, Smith et al. 2016, Delikurt et al. 2015, Flynn et al. 2010, Murff, Byrne and Syngal 2004, Nippert et al. 2011, Plat et al. 2009, Sin et al. 2018, Wood et al. 2014). Research efforts seek to identify and overcome these barriers, but improvements in the process of care that take place as part of a research program often are not sustainable when the study ends. This problem is more pronounced in low-income, low-education, limited English proficiency, and minority populations (Koh et al. 2010, Roberts et al. 2019, Rana et al. 2018). Safety net medical care settings may find it difficult to translate these interventions into sustained practice improvements (Srinivasan et al. 2021).

The Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM) study evaluated ways to increase access to evidence-based genetic testing for hereditary cancer in low-income and low-literacy populations in diverse primary care settings (Mittendorf et al. 2021, Amendola et al. 2018). CHARM recruited adults who were at increased risk for hereditary cancer syndromes (HCS) based on family history and could benefit from genetic testing to inform the need for earlier and more frequent cancer surveillance or consideration of interventions for cancer risk reduction. In this paper, we describe how the implementation of the CHARM study at a low-resourced health system resulted in sustainable changes that allowed the work of genetic cancer risk assessment to continue, even after the study ended.

Methods

Setting

The CHARM study has been described elsewhere (Mittendorf et al. 2021, Mittendorf et al. 2022b). Briefly, CHARM investigators developed a novel, literacy-adapted electronic patient-facing family history risk assessment tool in Spanish and English using two clinically validated clinician-facing modules (B-RST™3.0 and PREMM5) that patients would complete outside of a clinical encounter on a portable electronic device or computer. If a patient screened at high risk for HCS, or lacked information about their family history, they received education about genetic testing and were invited to participate in the study. Risk assessment, pre-test genetic counseling, and informed consent for the study were all incorporated into this interactive tool, without the need of any clinician’s involvement. Study participants provided saliva for clinical genomic sequencing and were randomized to receive two styles of genetic counseling where their results from the genetic testing were disclosed. The participant’s clinical team also received results of genetic testing and counseling recommendations (Fig. 1). Recruitment for CHARM occurred at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) in Oregon and Southwest Washington and Denver Health (DH) in Denver, Colorado, from August 2018 to March 2020. Patients were eligible to participate if they were between the ages of 18 and 49 years and spoke English or Spanish. Here, we limit our discussion to implementation at DH given the unique challenges of conducting research in a low-resource environment.

DH is an integrated health care system with a robust primary care network that, at the time of the study, consisted of nine Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) located in Denver’s poorest neighborhoods and 18 school-based clinics, providing primary care to approximately 175,000 patients (about one-third of Denver County residents). As of 2019, 75% of DH patients lived in poverty, defined as having an income of less than 200% of the federal poverty level. Of the DH patient population, 59% self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, 21% needed Spanish medical interpretation, about 57% had Medicaid insurance, and 18% of patients were uninsured. Uninsured patients had access to care via an income-based sliding scale discount program.

Prior to implementation in the CHARM study, DH did not have the infrastructure in place to support the necessary work to identify or manage patients at risk for HCS. There was limited awareness of the importance of the topic and no standard workflow for identification and tracking of at-risk patients. Furthermore, in-house cancer genetic services were not available, so high-risk patients required a referral to outside institutions. These barriers resulted in a limited number of outgoing referrals to cancer-related genetic counseling services.

DH/CHARM partnership: early involvement of key stakeholders and intentional sustainability focus

To ensure that the CHARM intervention would be feasible to implement and sustain in the DH setting, this study was developed as a collaborative partnership between health services researchers and clinician scientists.

The key personnel at DH included a primary care physician (KA) who led cancer screening initiatives, as well as a medical oncologist (SO) with experience in cancer intervention research trials. Other key DH team members included a patient navigator (EM) and a research coordinator (SD), both of whom identified as Latinx, spoke both English and Spanish, and were experienced in research and clinical care of underserved patient populations. As subject matter experts in the target population and setting, these four DH team members understood the challenges of conducting health services research in a community setting and the clinical and systemic barriers experienced by DH patients. They provided input that would intentionally support not only study design but also sustainability of key study components in future clinical care beyond the study period. They provided input during grant proposal development, assisting in the design of a multimodal study intervention that would act on identified barriers of care for cancer genetic services. The DH team engaged early and directly in the development of the study protocol, the creation of all patient-facing materials, and recruitment and retention methodology.

As part of the study design process, DH study team members also sought input from their clinical colleagues, particularly those in gynecology, family medicine, and oncology, about perceived barriers to genetic testing and counseling in the clinical care setting at DH. The CHARM Study also formed a patient advisory committee (who included but were not limited to PJ and CR) that provided input on the development of study materials and study processes (including patients who preferred Spanish) (Lindberg et al. 2022, O'Daniel et al. 2022).

Perceived barriers

During the early funding period of CHARM, the DH team readily identified several structural barriers that were limiting successful implementation of the study as well as long-term sustainability efforts. These barriers included:

-

1.

Lack of awareness of HCS: DH clinical colleagues reported limited awareness of HCS beyond their specialty areas, due to lack of formal training or continuing education, and were not comfortable identifying at-risk patients

-

2.

Collection of family history: The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (Owens et al. 2019) recommends collection of family history as a first step to identify individuals at risk of HCS. Prior to CHARM, DH had no standard processes or tracked metrics for collecting family history of cancer

-

3.

Documentation of family history: Family history was not consistently documented in the electronic medical record (EMR), as it often competed with more pressing health concerns and was difficult to fit into the limited time allocated to clinic appointments and direct patient care. EMR data pull of family history documentation was measured pre and post intervention

-

4.

Outgoing referrals to cancer genetic services: Family history data needs to be evaluated for HCS risk to determine whether genetic counseling and testing is recommended. DH had only one genetic counselor whose practice was limited to antenatal care; thus, patients considered at-risk based on reported family history or personal history of cancer required a clinician’s referral to genetic counselors at outside institutions. Since these referrals are the last step in the pursuit of genetic testing of at-risk individuals, the number of referrals to genetic counseling services in the EMR was counted pre- and post-intervention as a measure of study impact

-

5.

Documentation of genetic test results: the EMR did not have functionality to easily identify results of genetic testing since these were performed at outside institutions. All results were uploaded into the EMR as generic “outside records” which were difficult to find

Results

Table 1 summarizes the barriers to HCS testing identified at DH and the solutions and outcomes as a result of the CHARM study.

-

1.

Lack of awareness of HCS at DH: To overcome this barrier, the DH team used the effort protected by the study’s funding to prepare educational modules on HCS and a list of cancer genetics resources. These modules are lasting resources to be used on an ongoing basis by the DH clinical team and can be easily updated as practice guidelines change. During the study, the HCS educational modules were presented to five primary care clinics and other provider groups attuned to HCS and genomics (women’s care, gastroenterology, and oncology). A total of 14 educational sessions were held, across nine clinical sites and four departmental meetings within DH, with a total attendance of 161 clinicians and 219 key stakeholders, which included patient navigators in the gastrointestinal (GI) lab, nursing, and cancer work groups.

-

2.

Collection of family history: To support the study protocol, the team developed a patient-facing, electronic family history collection and risk assessment application that was accessible independent of the clinical visit or involvement of the clinician (Mittendorf et al. 2022b, Mittendorf et al. 2022a). During the study period, 364 DH patients successfully completed the family history collection tool that was developed for CHARM.

-

3.

Documentation of family history: To create a sustainable change around family history collection, DH developed a standard workflow for documenting family history in the EMR, with ongoing work exploring the implementation of family history collection tools in key clinical areas, including the mammography and endoscopy units. This has resulted in an increase from 65% pre-intervention to 70% post-intervention of family history documentation in the EMR of patients who receive primary care services in the first 18 months of implementation.

-

4.

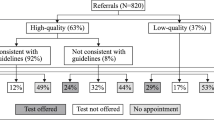

Outgoing referrals to cancer genetic services: Prior to CHARM, few referrals per year were placed for patients at risk for HCS, and most of these were for patients who already had a diagnosis of cancer. The CHARM family history tool (Mittendorf et al. 2021) streamlined this process, eliminating the need for a genetic counselor to review the family history data. Genetic testing and counseling were offered within the study without the need for a clinic visit or outside referral. After the study, with the increased awareness of HCS, resource compilation, and implementation of standardized workflows for the components above, DH saw a marked increase in referrals to genetics for the indication of evaluation of HCS during CHARM which persisted post-intervention (Fig. 2). In 2021, DH placed 427 referrals to genetics for this indication alone compared to 240 in 2020. In 2022, 212 referrals were placed in the first 4 months alone, suggesting that this change will be sustained.

-

5.

Documentation of genetic test results: The DH team created a specific bar code label and process to clearly identify genetic test results in the EMR. “Genetic results” identified by the newly created label increased during study enrollment (2019–2020) due to the number of participants receiving genetic results as part of the study and continues to be used at a lower steady-state level in 2021 and 2022, after study completion, as part of ongoing regular clinical care (Fig. 3).

Discussion

DH is a safety net institution and prior to the CHARM Study had no formal infrastructure in place to offer hereditary cancer risk assessment or cancer genetic services. By participating in CHARM, DH created a lasting roadmap for the ongoing development of such services, while making key contributions to the success of the research project. Instrumental to the success of and post-study sustainability of the CHARM intervention was the early involvement of key stakeholders, including clinical leaders, a variety of providers, and a patient advisory committee. While early engagement of community partners is an essential feature of sustainable translational research (Barger et al. 2019, Forsythe et al. 2016, LeClair et al. 2020), it is critical to choose the right partners who have leadership buy-in for long-term sustainability. Another characteristic of this partnership was the intentional focus on developing and creating a sustained improvement in the identification and care for hereditary cancer patients for our institution, adopted by all partners in the project, starting long before the first participant was enrolled.

Once key coinvestigators and team personnel were identified, the process started by raising awareness of the importance of HCS via educational modules delivered to 161 clinicians and 219 key stakeholders throughout the institution. The DH team then established best practices and standardized workflows for the collection of family history, documentation of high-risk patients within the problem list, and creation of a specific label in the EMR to flag genetic testing results for easy identification. While these were implemented as part of the study protocol, because of the sustainability of the intervention design, these workflows continue to be used clinically after study completion.

Due to increased awareness and workflows created as part of the study, DH has seen a substantial and sustained increase in the number of referrals to genetics for HCS, from less than 100 referrals pre-intervention to over 400 referrals a year post-intervention, reflecting a considerable positive impact in the health system, paving the way to identifying more patients at risk for HCS. It is worth noting that the CHARM study offered free genetic testing and posttest genetic counseling to participants, which theoretically should have decreased the number of genetic counseling referrals post-intervention. The fact that it did not, despite the recruitment success of the study, speaks to the larger impact of the study in the institution, likely grounded on the increased awareness of the topic of HCS for the entire healthcare system. We observed only a modest increase in family history documentation in comparison to the increase in genetics referrals, suggesting that the strongest contributor of the study’s lasting impact was the increased awareness and understanding of HCS. This demonstrates that it is critical that clinicians understand why collecting this information is important in order to act upon this information by recommending further evaluation via a referral.

A remaining challenge is the actual completion of genetic counseling and testing when this resource requires a referral to an outside institution unfamiliar to the patient. Anecdotally, DH clinicians report that many patients do not end up setting up appointments and/or getting tested. To eliminate the need for outside referrals, DH is working toward expansion of in-house genetic counseling services to include HCS. This will increase timely access to genetic services and improve care access and coordination for DH patients.

Participating in the CHARM study has led to several important and sustainable changes at DH. DH providers have recognized that risk assessments for HCS can be completed without interrupting clinical workflows in a busy, under-resourced primary care setting by using patient-facing or staff-directed screening tools for HCS outside of the clinical encounter with a provider. Currently, the DH team is exploring implementing risk assessment tools in the mobile mammography van to increase access in other underserved areas. Finally, DH is establishing a prospective HCS registry, with the long-term goal of setting up a medical home with an established care team for these patients. The team will be using a model championed by Kaiser Permanente Colorado, which leverages the EMR and allows for tracking of HCS patients.

Conclusion

The CHARM study is an example of a mutually beneficial academic-community partnership. Our approach outlines a template for researchers and clinical leaders seeking to design sustainable interventions to improve access to cancer genetic services in a safety net setting for underserved populations. Key to its success was the early involvement of the appropriate clinical leadership and clinician stakeholders, patient engagement in the research process, and dedicated and intentional efforts to make the research venture endure past the funding period by focusing on infrastructure building and knowledge transfer.

Data Availability

Data: Not applicable

Materials: study materials available at https://cser-consortium.org/

References

Amendola LM, Berg JS, Horowitz CR, Angelo F, Bensen JT, Biesecker BB, Biesecker LG, Cooper GM, East K, Filipski K, Fullerton SM, Gelb BD, Goddard KAB, Hailu B, Hart R, Hassmiller-Lich K, Joseph G, Kenny EE, Koenig BA et al (2018) The Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research Consortium: integrating genomic sequencing in diverse and medically underserved populations. Am J Hum Genet 103:319–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.08.007

Barger S, Sullivan SD, Bell-Brown A, Bott B, Ciccarella AM, Golenski J, Gorman M, Johnson J, Kreizenbeck K, Kurttila F, Mason G, Myers J, Seigel C, Wade JL 3rd, Walia G, Watabayashi K, Lyman GH, Ramsey SD (2019) Effective stakeholder engagement: design and implementation of a clinical trial (SWOG S1415CD) to improve cancer care. BMC Med Res Methodol 19:119. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0764-2

Cragun D, Weidner A, Lewis C, Bonner D, Kim J, Vadaparampil ST, Pal T (2017) Racial disparities in BRCA testing and cancer risk management across a population-based sample of young breast cancer survivors. Cancer 123:2497–2505. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30621

Delikurt T, Williamson GR, Anastasiadou V, Skirton H (2015) A systematic review of factors that act as barriers to patient referral to genetic services. Eur J Hum Genet 23:739–745. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2014.180

Flynn BS, Wood ME, Ashikaga T, Stockdale A, Dana GS, Naud S (2010) Primary care physicians' use of family history for cancer risk assessment. BMC Fam Pract 11:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-11-45

Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, Sabharwal R, Rein A, Konopka K, Frank L (2016) Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J Gen Intern Med 31:13–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z

Koh HK, Oppenheimer SC, Massin-Short SB, Emmons KM, Geller AC, Viswanath K (2010) Translating research evidence into practice to reduce health disparities: a social determinants approach. Am J Public Health 100(Suppl 1):S72–S80. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2009.167353

LeClair AM, Kotzias V, Garlick J, Cole AM, Kwon SC, Lightfoot A, Concannon TW (2020) Facilitating stakeholder engagement in early stage translational research. PLoS One 15:e0235400. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235400

Lindberg NM, Mittendorf KF, Duenas DM, Anderson K, Koomas A, Kraft SA, Okuyama S, Shipman KJ, Vandermeer ML, Goddard KA, Wilfond BS, McMullen C (2022) Engaging patient advisory committees to inform a genomic cancer risk study: lessons for future efforts. Perm J 26:28–39. https://doi.org/10.7812/tpp/21.091

McCarthy AM, Bristol M, Domchek SM, Groeneveld PW, Kim Y, Motanya UN, Shea JA, Armstrong K (2016) Health care segregation, physician recommendation, and racial disparities in BRCA1/2 testing among women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:2610–2618. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.66.0019

Meyer LA, Anderson ME, Lacour RA, Suri A, Daniels MS, Urbauer DL, Nogueras-Gonzalez GM, Schmeler KM, Gershenson DM, Lu KH (2010) Evaluating women with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: missed opportunities. Obstet Gynecol 115:945–952. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da08d7

Mittendorf KF, Kauffman TL, Amendola LM, Anderson KP, Biesecker BB, Dorschner MO, Duenas DM, Eubanks DJ, Feigelson HS, Gilmore MJ, Hunter JE, Joseph G, Kraft SA, Lee SSJ, Leo MC, Liles EG, Lindberg NM, Muessig KR, Okuyama S et al (2021) Cancer Health Assessments Reaching Many (CHARM): a clinical trial assessing a multimodal cancer genetics services delivery program and its impact on diverse populations. Contemp Clin Trials 106:106432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2021.106432

Mittendorf KF, Lewis HS, Duenas DM, Eubanks DJ, Gilmore MJ, Goddard KAB, Joseph G, Kauffman TL, Kraft SA, Lindberg NM, Reyes AA, Shuster E, Syngal S, Ukaegbu C, Zepp JM, Wilfond BS, Porter KM (2022a) Literacy-adapted, electronic family history assessment for genetics referral in primary care: patient user insights from qualitative interviews. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 20:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-022-00231-3

Mittendorf KF, Ukaegbu C, Gilmore MJ, Lindberg NM, Kauffman TL, Eubanks DJ, Shuster E, Allen J, McMullen C, Feigelson HS, Anderson KP, Leo MC, Hunter JE, Sasaki SO, Zepp JM, Syngal S, Wilfond BS, Goddard KAB (2022b) Adaptation and early implementation of the PREdiction model for gene mutations (PREMM(5)™) for lynch syndrome risk assessment in a diverse population. Familial Cancer 21:167–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-021-00243-3

Murff HJ, Byrne D, Syngal S (2004) Cancer risk assessment: quality and impact of the family history interview. Am J Prev Med 27:239–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.05.003

Nippert I, Harris HJ, Julian-Reynier C, Kristoffersson U, Ten Kate LP, Anionwu E, Benjamin C, Challen K, Schmidtke J, Nippert RP, Harris R (2011) Confidence of primary care physicians in their ability to carry out basic medical genetic tasks-a European survey in five countries-Part 1. J Community Genet 2:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-010-0030-0

O'Daniel JM, Ackerman S, Desrosiers LR, Rego S, Knight SJ, Mollison L, Byfield G, Anderson KP, Danila MI, Horowitz CR, Joseph G, Lamoure G, Lindberg NM, McMullen CK, Mittendorf KF, Ramos MA, Robinson M, Sillari C, Madden EB (2022) Integration of stakeholder engagement from development to dissemination in genomic medicine research: approaches and outcomes from the CSER Consortium. Genet Med 24:1108–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.008

Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, Kubik M, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Pbert L, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW, Wong JB (2019) Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Jama 322:652–665. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.10987

Plat AW, Kroon AA, Van Schayck CP, De Leeuw PW, Stoffers HE (2009) Obtaining the family history for common, multifactorial diseases by family physicians. A descriptive systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract 15:231–242. https://doi.org/10.3109/13814780903447572

Rana HQ, Cochrane SR, Hiller E, Akindele RN, Nibecker CM, Svoboda LA, Cronin AM, Garber JE, Lathan CS (2018) A comparison of cancer risk assessment and testing outcomes in patients from underserved vs. tertiary care settings. J Community Genet 9:233–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-017-0347-z

Roberts MC, Clyne M, Kennedy AE, Chambers DA, Khoury MJ (2019) The current state of funded NIH grants in implementation science in genomic medicine: a portfolio analysis. Genet Med 21:1218–1223. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2017.180

Shields AE, Burke W, Levy DE (2008) Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: results of a national survey. Genet Med 10:404–414. https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181770184

Sin M, McGuinness JE, Trivedi MS, Vanegas A, Silverman TB, Crew KD, Kukafka R (2018) Automatic genetic risk assessment calculation using breast cancer family history data from the EHR compared to self-report. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018:970–978

Smith CE, Fullerton SM, Dookeran KA, Hampel H, Tin A, Maruthur NM, Schisler JC, Henderson JA, Tucker KL, Ordovás JM (2016) Using genetic technologies to reduce, rather than widen, health disparities. Health Aff (Millwood) 35:1367–1373. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1476

Srinivasan T, Sutton EJ, Beck AT, Cuellar I, Hernandez V, Pacyna JE, Shaibi GQ, Kullo IJ, Lindor NM, Singh D, Sharp RR (2021) Integrating genomic screening into primary care: provider experiences caring for Latino patients at a community-based health center. J Prim Care Community Health 12:21501327211000242. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501327211000242

Wood ME, Kadlubek P, Pham TH, Wollins DS, Lu KH, Weitzel JN, Neuss MN, Hughes KS (2014) Quality of cancer family history and referral for genetic counseling and testing among oncology practices: a pilot test of quality measures as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative. J Clin Oncol 32:824–829. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.51.4661

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Laura Amendola, Marian Gilmore, Jamilyn Zepp, Bradley Rolf, Elizabeth Shuster, Kathryn Porter, Stephanie Kraft and Galen Joseph for their contributions to the project, as well as Ana Reyes and Christopher Peterson for administrative assistance.

Funding

This work was funded as part of the Clinical Sequencing Evidence-Generating Research (CSER) consortium funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute with co-funding from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The CSER consortium represents a diverse collection of projects investigating the application of genome-scale sequencing in different clinical settings including pediatric and adult subspecialties, germline diagnostic testing and tumor sequencing, and specialty and primary care. This work was supported by a grant from the National Human Genome Research Institute (U01HG007292; MPIs: Wilfond, Goddard), with additional support from U24HG007307 (Coordinating Center). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Sonia Okuyama, Katherine P. Anderson, Larissa L. White and Heather S. Feigelson. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Sonia Okuyama and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All the procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (Delikurt et al. 2015). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

The KPNW IRB approved this study, and all collaborating IRBs ceded to KPNW except Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Columbia University, who approved the study separately.

Conflict of interest

Sonia Okuyama, Larissa L White, Katherine P Anderson, Elizabeth Medina, Michael C. Leo, Joanna E. Buckley, Katrina Goddard, Chelese Ransom, Paige Jackson, Tia L. Kauffman, Benjamin S Wilfond, and Heather S. Feigelson declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Kathleen F. Mittendorf discloses salary support from NIH/NCI for the development of the PREMM model (R01CA132829, PI: Syngal; role: co-investigator), salary support from NIH/NCI (U01CA232829; MPIs: Wiesner & Orlando; role: study personnel), and salary support from NIH/NHGRI (U01HG011181; MPIs Roden, Velez Edwards, & Wei; role: study personnel) for studies involving the implementation of the MeTree family history tool including in safety-net settings and salary support from funds awarded to their institution by GE Healthcare (PI: Park; role: study personnel).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okuyama, S., White, L.L., Anderson, K.P. et al. Evaluating cancer genetic services in a safety net system: overcoming barriers for a lasting impact beyond the CHARM research project. J Community Genet 14, 329–336 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-023-00647-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12687-023-00647-x