Abstract

Background

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare disease resulting from the overactivation of the immune system due to under regulation of cytotoxic lymphocytes, macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells. HLH is associated with malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders and rarely AIDS and is rapidly fatal.

Case presentation

This case report identified a 53 year old male with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) who presented with neutropenic fever of unknown origin. He had two previous hospitalizations prior to the hospitalization diagnosing HLH. The first led to a diagnosis of drug fevers in the setting of treatment for thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and subsequent hospitalization led to empiric treatment of hospital acquired pneumonia after workup for intermittent fevers was negative. He was discharged but readmitted 10 days after for recurrence of neutropenic fevers. During this final hospitalization, he was found to have elevated liver enzymes, ferritin, triglycerides and soluble IL-2 receptor with persistent fevers, new splenomegaly and bicytopenia meeting the 2004 HLH criteria. Bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of HLH as well as EBV associated large B-cell lymphoma. The patient improved on treatment with steroids, rituximab, tocilizumab, and chemotherapy but ultimately passed away due to refractory septic shock from multi-drug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Conclusion

This novel case highlights a patient diagnosed with HLH in the setting of several risk factors for the disease, including AIDS, B-cell lymphoma and EBV. Additionally, this case highlights the importance of early consideration of HLH in the setting of neutropenic fever without clear infectious etiology and search for malignancy associated reasons for HLH especially in immunocompromised patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive, rapidly fatal, and often misdiagnosed hyper-activation of the immune system that can be seen in a variety of malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, and rarely HIV [1, 2]. This pathology results in excessive production of cytokines which in turn results in cellular destruction and eventual organ failure [3]. We present the case of a 53-year-old male with HIV/AIDS who was admitted with neutropenic fever in the setting of bone marrow failure, which preceded a diagnosis of HLH from EBV related Large B Cell Lymphoma.

2 Case presentation

A 53-year-old African-American male with a past medical history of HIV with CD4 count of 27 and undetectable viral load, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, colitis status post hemicolectomy, polysubstance abuse who presented with fever of unknown origin. Notably, the patient has had two prior admissions three months before this presentation. On his first admission, he was diagnosed with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, responsive to Caplacizumab and prednisone. His hospital course was complicated by intermittent persistent fevers, which was eventually attributed to drug fever. There was consideration of DRESS syndrome during this admission although the patient did not have eosinophilia, which one study suggests is present in 97% of patients with DRESS syndrome [4]. Patient was discharged home but readmitted two weeks later with failure to thrive and was found to have neutropenic fevers of unknown origin. He underwent extensive workup for infectious etiology. CT chest showed persistent stable pulmonary nodules for which bronchoscopy was performed with lavage cytopathology significant only for colonized rare candida spp. He was found to have Epstein–Barr virus viremia. However, with no clear source he was treated empirically for hospital acquired pneumonia. He was discharged after resolution of his fevers to subacute rehab.

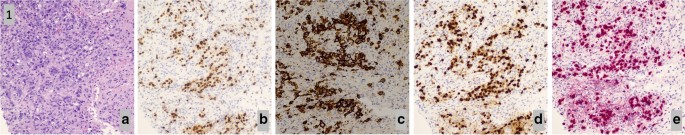

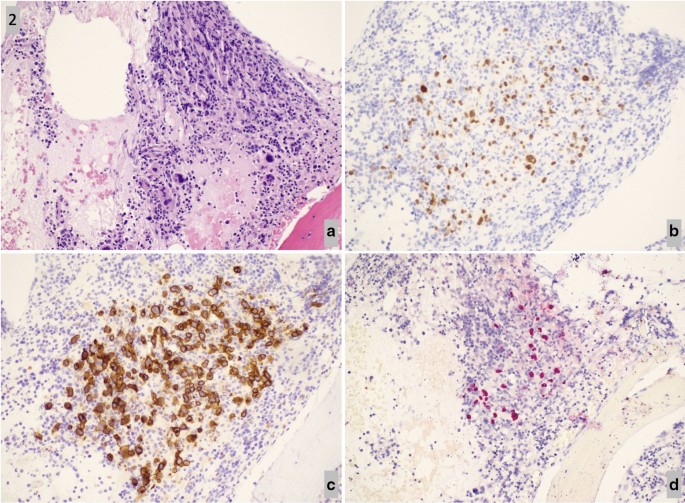

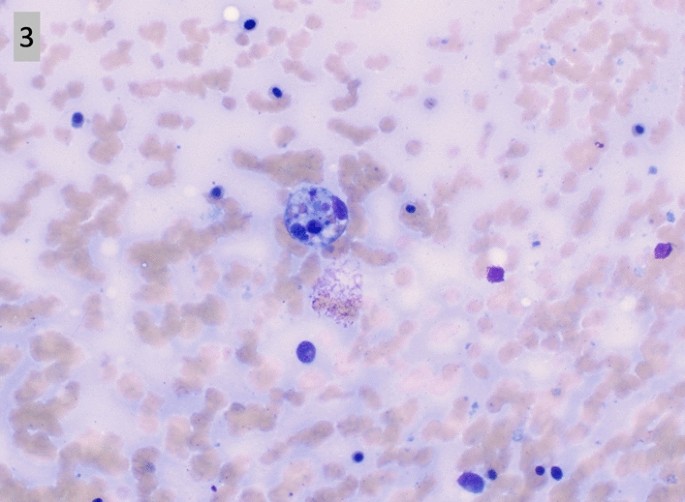

Ten days after discharge, he was readmitted for recurrence of neutropenic fevers, with absolute neutrophil count 532. Extensive workup revealed persistent fevers, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, elevated LFTs, ferritin, triglycerides, and soluble IL-2 receptor, meeting the 2004 hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) criteria [5] (Tables 1, 2). Lymph node biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of EBV associated lymphoma (Fig. 1a–e). Bone marrow biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of immunodeficiency associated large B-cell lymphoma with EBV associated HLH (Fig. 2a–d). Patient was treated with a combination of steroids, rituximab, tocilizumab, and chemotherapy. Initially, the patient’s status improved but unfortunately the patient ultimately expired 5 days after intensive care unit (ICU) downgrade due to refractory septic shock secondary to multidrug resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae.

3 Discussion

HLH is a rare disease associated with overactivation of the immune system, specifically the under regulation of cytotoxic lymphocytes, macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells. While primarily a pediatric entity, cases have been diagnosed in adults, with a predisposition for males, mean age range of 41–67 years, and an estimated incidence rate of 1 per 800,000 people [6, 7]. Etiology is poorly defined but associated with genetic abnormalities specifically impairing perforins (a key delivery molecule for proapoptotic granzymes) [8], especially in the pediatric population. HLH associated with genetic causes is termed primary HLH. Our patient unfortunately cannot be excluded from the diagnosis of primary HLH as genetic causes were not tested during his admission. Nonetheless, our patient had multiple associations to make the likely diagnosis of secondary HLH.

In adults, a 2015 single center study found the etiology of secondary HLH was commonly due to infection (41.1%), followed by malignancies (28.8%). Of the infectious etiologies, HIV and EBV both were the most common causes (5/30 and 5/30) [2]. Viral load of EBV quantified by PCR correlates with disease severity [6]. Interestingly, in our patient, his EBV viral load from previous admission was 38,000. As he further deteriorated and the diagnosis of HLH became clearer, his viral load increased to 97,900 (Table 1). Of the malignancy related causes, B-cell lymphoma was the most common, with 10 out of 21 patients [2]. It is likely that the disease driving the patient’s presentation was a combination of EBV, HIV and large B cell lymphoma.

In our patient, the diagnosis of lymphoma was made on lymph node biopsy (Fig. 1a–e) prior to the pathological diagnosis of HLH seen on bone marrow biopsy (Fig. 2a–d). This diagnosis of lymphoma was EBV-related as evidenced by the positivity of EBER in-situ hybridization on lymph node and bone marrow biopsy. To our knowledge, there have been no retrospective or prospective studies defining the incidence of HLH with underlying HIV, EBV, and B cell lymphoma. We found one case report describing a similar patient presentation [9]. Although NK function and genetics were not performed on our patient, our patient had clear triggers for HLH secondary to immune activation, rather than underlying genetic defects in lymphocytes, thus classifying his case under HLH disease rather than syndrome. Regardless, without treatment, HLH has a high mortality due to multiorgan failure.

According to the HLH-2004 trial, which determined the diagnostic criteria for HLH, histological identification of HLH was not required to make a definitive diagnosis. Nonetheless, in patients with clinical suspicion for HLH, bone marrow biopsy to search for hemophagocytosis or underlying malignancy could help aid in the diagnosis [10]. Further complicating the picture, the presence of hemophagocytosis in bone marrow biopsies was neither sensitive nor specific for the diagnosis of HLH. On the admission preceding the admission ultimately diagnosing HLH, our patient had a bone marrow biopsy that was negative for hemophagocytosis. This leads us to question whether bone marrow biopsy should be performed on all patients suspected of HLH [9]. According to a retrospective analysis of HLH confirmed patients, bone marrow biopsy only showed hemophagocytosis in 70% of patients [11]. In our case, bone marrow biopsy showed hemophagocytosis (Fig. 3) while also distinguishing the underlying etiology of HLH (Fig. 2a–d). Our patient case highlights the importance of early consideration of HLH in the setting of neutropenic fever without clear infectious etiology. Additionally, this highlights the importance of identifying the etiology of secondary HLH, including malignancy.

a–e Retroperitoneal lymph node biopsy. H&E stained core biopsy of the retroperitoneal lymph node shows sheets and clusters of large, pleomorphic cells, with some showing prominent nucleoli. Numerous mitoses are observed. (a, H&E). By immunostain, the cells are positive for Pax-5 (b), CD30 (c), and MUM-1 (d). EBER in-situ hybridization is positive (e)

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during this case report.

Abbreviations

- HLH:

-

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

- EBV:

-

Ebstein–Barr virus

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

References

Asanad S, Cerk B, Ramirez V. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) secondary to disseminated histoplasmosis in the setting of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018;20:15–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mmcr.2018.01.001.

Otrock ZK, Eby CS. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcomes of adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol. 2015;90(3):220–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.23911.

Emiloju OE, Gupta S, Arguello-Guerra V, Dourado C. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis in an AIDS patient with kaposi sarcoma: a treatment dilemma. Case Rep Hematol. 2019;2019:7634760. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7634760.

Skowron F, Bensaid B, Balme B, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): clinicopathological study of 45 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(11):2199–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.13212.

Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, Filipovich AH, McClain KL. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118(15):4041–52. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127.

Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Epstein–Barr virus-associated T and NK-cell lymphoproliferative diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71–71. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00071.

Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet (British edition). 2014;383(9927):1503–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61048-X.

Stepp SE, Dufourcq-Lagelouse R, Le Deist F, et al. Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Science. 1999;286(5446):1957–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5446.1957.

Hippensteel JA, Neumeier A. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in AIDS associated EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. B46 Crit Care Case Rep Hematol Oncol Rheumatol Immunol. A3392–A3392.

Gars E, Purington N, Scott G, et al. Bone marrow histomorphological criteria can accurately diagnose hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2018;103(10):1635–41. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2017.186627.

Rivière S, Galicier L, Coppo P, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome in adults: a retrospective analysis of 162 patients. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1118–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.034.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Payal Sojitra, MD and Virian D. Serei, MD, PhD for providing the histological images and captions in this case report.

Funding

There was no funding for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL and AN assembled, analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the hematological disease. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Noveihed, A., Liang, S., Glotfelty, J. et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a rare disease unveiling the diagnosis of EBV-related large B cell lymphoma in a patient with HIV. Discov Onc 13, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-022-00476-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-022-00476-3