Abstract

Objectives

Incarcerated young men commonly experience problems with impulsivity and emotional dysregulation. Mindfulness training could help but the evidence is limited. This study developed and piloted an adapted mindfulness-based intervention for this group (n = 48).

Methods

Feasibility of recruitment, retention, and data collection were assessed, and the effectiveness of mindfulness training measured using validated questionnaires. Twenty-five qualitative interviews were conducted to explore experiences of the course, and barriers and facilitators to taking part.

Results

The findings indicated that recruitment and retention to mindfulness training groups was a challenge despite trying various adaptive strategies to improve interest, relevance, and acceptability. Quantitative data collection was feasible at baseline and post-course. There were significant improvements following training in impulsivity (effect size [ES] 0.72, 95% CI 0.32–1.11, p = 0.001), mental wellbeing (ES 0.50; 95% CI 0.18–0.80; p = 0.003), inner resilience (comprehensibility ES 0.35; 95% CI − 0.02–0.68; p = 0.03), and mindfulness (ES 0.32; 95% CI 0.03–0.60; p = 0.03). The majority (70%) of participants reported finding the course uncomfortable or disconcerting at first but if they chose to remain, this changed as they began to experience benefit. The body scan and breathing techniques were reported as being most helpful. Positive experiences included better sleep, less stress, feeling more in control, and improved relationships.

Conclusions

Developing and delivering mindfulness training for incarcerated young men is feasible and may be beneficial, but recruitment and retention may limit reach. Further studies are required that include a control group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Offending among young people is a concern worldwide (Sabol et al. 2009), and is associated with socio-economic deprivation, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), low educational attainment, and mental health problems (Dodge and Pettit 2003; Farrington 2003; Ou and Reynolds 2010; Singleton et al. 1998). Such factors contribute to delayed maturational development and impaired social skills (Monahan et al. 2009, 2013; Steinberg 2010; Steinberg et al. 2008; Steinberg et al. 2015) and may impair neural development in brain areas that exert the cognitive control required for emotional and behavioral regulation (Abram et al. 2004).

Incarcerated young people are particularly vulnerable. Once incarcerated, the care received is often sub-optimal (Audit Scotland 2012; Callaghan et al. 2003; Carswell et al. 2004; Chitsabesan et al. 2006). Effective interventions are required to help incarcerated young people manage stress and improve their cognitive and emotional skills. The most commonly used approach is cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), although the evidence-base for this among young people who offend is limited (Andrews et al. 1990; Lipsey 1995; Lösel 1995; Sapouna et al. 2011). Further innovative interventions are required that are safe, effective, acceptable, and accessible to the young people who use them (Sapouna et al. 2011; Ward et al. 2012). Augmentation of natural protective factors, individual strengths, and positive treatment alliances is receiving increasing attention (McNeill 2006; McNeill et al. 2012).

One potential approach is mindfulness. Secularized mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are proposed to preferentially train attention, enhance emotional awareness and regulatory skills, and generate a shift in one’s sense-of-self (Hölzel et al. 2011), operating largely through enhanced mindfulness, cognitive flexibility, and meta-awareness (Gu et al. 2015; Kabat-Zinn 1982). Systematic reviews support MBIs as effective, both in clinical and non-clinical populations (Chiesa and Serretti 2010; De Vibe et al. 2012; Goyal et al. 2014; Grossman et al. 2004). In general, there is good quality evidence that MBIs improve anxiety and depression (Fjorback et al. (2011), are of use in addictive behaviors and substance misuse (Witkiewitz et al. 2013; Witkiewitz et al. 2005), improve cognitive function (Lao et al. 2016), and may be particularly relevant for those with a history of ACEs (Kuyken et al. 2015). Based on a web-survey of 2160 participants, Whitaker et al. (2014) reported that across a range of exposure to ACEs, greater dispositional mindfulness was associated with fewer health conditions, better health behavior, and better health related quality of life in adult years.

There is a growing evidence base supporting the utility of mindfulness-based interventions for children and young people (Biegel et al. 2009; Greenberg and Harris 2012; Semple 2010; Semple et al. 2010; Weare 2012; Zoogman et al. 2015). Zoogman et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis that included 20 studies (n = 1914) to determine the usefulness of mindfulness-based training for young people (age range of 6–21). Most of the interventions required adaptations to the original MBSR protocol. Mindfulness was useful overall, with a pooled effect size (ES) of 0.23. Clinical populations showed higher effects (ES 0.50) than non-clinical populations (ES 0.20). However, most of 20 studies were small pilot studies. Two more recent randomized control trials (RCTs) have also shown promising results. Sibinga et al. (2016) evaluated an adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program for low-income, minority, middle school public school students. Students (n = 300) were randomly assigned to either MBSR or health education. Compared with matched controls, MBSR participants had significantly lower levels of somatization, depression, negative affect, negative coping, rumination, self-hostility, and posttraumatic symptom severity. In the second RCT, Britton et al. (2014) examined the effects of a mindfulness meditation intervention on standard clinical measures of mental health and affect in middle school children. A total of 101 sixth-grade students were randomized to either an Asian history course with daily mindfulness meditation practice (intervention group) or an African history course with a matched experiential activity (active control group). Both groups showed comparable improvements on measures of mental health and affect but the mindfulness group were significantly less likely to develop suicidal ideation or thoughts of self-harm than controls.

Whether it is feasible to deliver MBIs to young people who offend remains unclear. A recent scoping review (Simpson et al. 2018) reported that the existing evidence is limited. Multiple different MBIs have been applied, with a wide range of different outcome measures, and study quality has generally been low. The optimal MBI for young people who offend is unknown.

Feasibility studies estimate important parameters needed for refining programs and developing larger studies. In the current study, we have developed, piloted, and investigated the feasibility of an adapted MBI for young men who offend. The research was guided by the United Kingdom (UK) Medical Research Council framework on developing and evaluating complex interventions. We had four objectives: (1) determine recruitment and retention to the MBI and study, (2) investigate feasibility of data collection and potential effectiveness of the mindfulness course (on impulsivity, mental wellbeing, inner resilience, mindfulness, and emotional regulation), (3) explore course participants’, prison staff, and the mindfulness teacher’s views on the course, and (4) optimize the intervention (reported elsewhere—Byrne 2017).

Method

Participants

All participants were recruited from Her Majesty’s Young Offenders Institute (HMYOI) Polmont, Scotland’s national holding facility, which exclusively houses young men (aged 16–21), and is the largest such institute in the UK. Inclusion criterion was (1) age between 18 and 21 years (representing the bulk of the population in the institute). Exclusion criteria were (1) active psychosis or suicidality, (2) being on remand or having an identified release date that would coincide with the course, and (3) being incarcerated for committing a sexual offense (the mindfulness teacher did not have appropriate clinical skills to work with this group). In addition, HMYOI Polmont forensic psychology staff reserved the right to exclude any individual where clinical judgment deemed an individual unsuitable.

Procedure

A pre-post-study design was used. As this was a feasibility study, a power calculation was not appropriate (Arain et al. 2010). Trainee forensic psychologists at HMYOI Polmont acted as ‘recruitment managers,’ having experience in both treatment of mental health problems and risk assessment/management. Psychology staff received a clinician information sheet to guide the screening process; other HMYOI staff were given a staff information sheet detailing the aims and objectives of the study. Screened participants were invited to an introductory session with the mindfulness teacher and, following that, a study information session with the researcher (SS). Both sessions were delivered to small groups of young men (n = 5–10), typically 1 to 2 weeks before each mindfulness course commenced and usually lasting 20–30 min each. The introductory sessions explained the rationale for mindfulness, provided ‘taster’ experience of the practices, tried to establish realistic expectations, identified possible challenges, emphasized the need for active participation, and allowed for participant questions. The study information sessions covered the research aspect of the study, outlined data collection procedures, described how data would be used, emphasized the voluntary nature of taking part, and allowed for participant questions. Participant information sheets were provided at this time. Those young men expressing an interest in taking part were invited to provide their informed consent and to complete baseline questionnaire measures. Participants were informed they could withdraw from the intervention/study at any time without this affecting their treatment in the institute. There were no financial incentives but all young men who completed the course were awarded a certificate of attendance.

The courses were led by a 26-year-old male mindfulness teacher, who has a Masters Degree in Applied Positive Psychology from the University of Pennsylvania and has trained in mindfulness with both the University of Bangor and the University of Aberdeen in the UK. He has extensive experience of teaching mindfulness to disadvantaged young people, as the founder of a charity (https://youthmindfulness.org/). At the time of the study, he had been practicing mindfulness personally for 8 years with a daily meditation practice. However, as he did not have a clinical background in mental health, he had regular access to the forensic psychology team, and SWM who is a medical practitioner with experience in psychiatry.

The first course iteration was based on standard MBSR, which is of 8 weeks duration, mainly experiential and psycho-educational with considerable in-session experience aimed at developing mindfulness skills through practice, group interaction and discussion. In addition, participants are encouraged to integrate this new learning into everyday living through both formal (daily meditation practices) and informal practices (bringing mindful awareness to cognitions, sensations, emotions and behaviors during day-to-day living, such as walking and eating). Over the subsequent iterations (seven in total), modifications were made to meet the needs of the young men. These included lengthening the course from eight to 10 weeks, shortening the meditation practices, structuring sessions to make them more simple and accessible, and minimizing form filling. The educational content was adapted to allow for low levels of reading comprehension, diverse learning styles, and low attention. Fun and games were introduced, including simple exercises to illustrate psychological concepts and improve understanding of mindfulness. Irrespective of these modifications, each course retained the three ‘core components’ of, standard MBSR (awareness of the breath, the body scan, and mindful-movement) (see Byrne 2017 for a more detailed description of the developmental process).

Measures

Quantitative Data

The feasibility of recruiting, retaining, and following-up participants was assessed. Outcome measures, collected at baseline and post-intervention, were piloted over the first two groups to test their suitability and identify any difficulties with reading, comprehension, and completion. Recruitment and retention rates to the course were determined by recording the number of potential participants who were approached, expressed interest rate, and subsequently consented to take part. Session attendance records were kept by the mindfulness teacher.

Participant-reported measures included impulsivity, mental wellbeing, inner resilience, mindfulness, and emotional regulation (see Table 1). The Teen Conflict Survey (TCS) scores highly on internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha, α = .81) among incarcerated young men (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2012). Patton et al. (1995) reported good internal consistency coefficients for the Barret Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11) for psychiatric patients (α = .83), individuals with a substance abuse history (α = .79), and incarcerated males (α = .80). The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) demonstrates good to excellent internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .78 to .95 in various studies and populations (Sánchez-López and Dresch 2008; Jackson 2007). A systematic review reported the Sense Of Coherence (SOC-13) as having good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .70 to .92) (Eriksson and Lindström 2005). Internal consistency for the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM) is good, with α = .81 (Greco et al. 2011), as is the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .78 to .92 (Park et al. 2013). Additionally, Himelstein et al. (2012) reported a high internal consistency for the MAAS in a study with incarcerated young men (α = .94). Finally, internal consistency for the Difficulty with Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS) is also high (α = .93) (Gratz and Roemer 2004). For pragmatic reasons, data collection sessions were conducted in small groups, supervised by the researcher (SS) and a recruitment manager, in case of comprehension difficulties.

Qualitative Data

Semi-structured interviews were conducted, by the main author (SS), with course participants, prison staff, and the mindfulness teacher. These were used to determine how the young men experienced the course, its accessibility and acceptability to them, how the mindfulness teacher found delivering the course, how prison staff saw the course, and to identify barriers and facilitators to recruitment and retention.

Data Analyses

Quantitative Data

All measures were assessed using the Flesch-Kincaid readability test (Kincaid et al. 1975). Data were explored using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, percentages), and paired t tests to assess change scores between baseline and post-intervention. Differences are reported using p values to determine significance, and standardized effect sizes (ES) (Cohen’s ‘d’) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Effect sizes were classified as ‘small’ (≥ 0.2), ‘medium’ (≥ 0.5), and ‘large’ (≥ 0.8). All analysis was carried out using SPSS v22.

Qualitative Data

Thematic analyses were used as a means of organizing and presenting findings (Richie et al. 2003), guided by the seven-step approach suggested by Ziebland and McPherson (2006). This involves verbatim transcription of recorded interviews (Transcription), reading and reflection (Thinking about the data), and identification of initial themes (Coding). Data were then grouped together under similar headings (Analysis), and a summary of all the issues within each code was then produced (One Sheet Of Paper method– OSOP). Finally, findings were rechecked by all three researchers (Testing and confirming findings), before the ‘story’ was then presented (Write up).

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participant characteristics (n = 48) are shown in Table 2. Most participants were unemployed prior to their incarceration (n = 28; 58.3%), just under half left full time education without a formal qualification (n = 20; 41.7%), and over half had previously been incarcerated (n = 27; 56.3%).

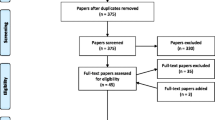

Recruitment and Retention

Figure 1 shows participant flow through the study. In total, 200 young men were approached and 62 (31%) expressed interest. Fifty-two (26%) started one of the seven MBI courses, and 25 (12%) completed a full course (defined as attending at least 50% of course sessions). Stated reasons for the low levels of recruitment and retention included the lower status of the course compared to other courses within HMYOI Polmont; stigma due to the association between the course and the prison mental health services; institutional and organizational barriers, competing agendas (e.g., prison staff placing young men on programmes other than the mindfulness course); and prison staff being skeptical about mindfulness. In addition, participants’ vulnerability to peer opinion and the unfamiliarity of mindfulness featured strongly.

Quantitative Outcomes

Forty-eight (92%) of participants completed baseline measures, with 35 (73%) completing measures post-intervention. Statistical analyses between baseline and post-intervention follow-up (n = 32) are shown in Table 3. Impulsivity scores reduced on both the TCS (ES 0.72, 95% CI 0.32–1.11; p = 0.001) and the BIS-11 with medium effect sizes (ES 0.50; 95% CI 0.21–0.76; p = 0.0.01). Further analysis of the three BIS-11 first order factors showed reductions in ‘attentional’ (ES 0.44; 95% CI 0.15–0.73; p = 0.005), ‘motor’ (ES 0.39; 95% CI 0.02–0.78; p = 0.04), and ‘non-planning’ impulsiveness with small effect sizes (ES 0.36; 95% CI 0.08–0.63; p = 0.01). Of the BIS-11 first order factors, impulsivity was also reduced in ‘attention’ (ES 0.33; 95% CI 0.08–0.59; p = 0.01), ‘cognitive instability’ (ES 0.46; 95% CI 0.08–0.84; p = 0.01) ‘self-control’ (ES 0.37; 95% CI 0.08–0.66; p = 0.02), ‘cognitive complexity’ (ES 0.37; 95% CI 0.01–0.72; p = 0.04), ‘motor impulsiveness’ (ES 0.33; 95% CI − 0.05–0.70; p = 0.08), and ‘perseverance’ (ES 0.32; 95% CI − 0.08–0.72; p = 0.11).

Mental distress scores decreased on the GHQ-12 with a medium effect size (ES 0.50; 95% CI 0.18–0.80; p = 0.003). For inner resilience, the overall SOC-13 scores did not show significant improvements from pre- to post-intervention (ES 0.28; 95% CI − 0.08–0.65; p = 0.12). However, further analysis revealed a significant improvement on the ‘meaningfulness’ subscale (ES 0.35; 95% CI − 0.02–0.68; p = 0.03), improvements of borderline significance on the ‘comprehensibility’ subscale (ES 0.35; 95% CI − 0.03–0.73; p = 0.06), but no change in scores on the ‘manageability’ subscale (ES 0.007; 95% CI − 0.44–0.45; p = 0.97).

Mindfulness improved on the CAMM outcome measure with a small effect size (ES 0.32; 95% CI 0.03–0.60; p = 0.03), with a smaller and non-significant effect on the MAAS (ES 0.27; 95% CI − 0.08–0.62; p = 0.13).

Emotional regulation scores showed small, albeit non-significant, improvements overall (ES 0.32; 95% CI − 0.06–0.71; p = 0.09), and on some of the six subscales: Lack of Emotional Awareness (LEA) (ES 0.34; 95% CI − 0.10–0.79; p = 0.12), Non Acceptance of Emotional Responses (NAER) (ES 0.32; 95% CI − 0.05–0.69; p = 0.08), Limited Access to Emotional Regulation Strategies (LAERS) (ES 0.25; 95% CI − 0.15–0.66; p = 0.21), and Lack of Emotional Clarity (LEC) (ES 0.22; 95% CI − 0.30–0.74; p = 0.39), Difficulty in Goal Directed Behavior (DGDB) (ES 0.20; 95% CI − 0.16–0.56; p = 0.26), with negligible effects on Impulse Control Difficulties (ICD) (ES 0.06; 95% CI − 0.30–0.42; p = 0.73). Figure 2 summarizes treatment effects showing a general positive trend for the intervention.

Qualitative Outcomes

Twenty young men who took part in the study were interviewed, including completers (n = 16) and non-completers (n = 4). Four main themes were identified: (1) Coming along, (2) Experience of the course, (3) Effects of the course, and (4) Future use.

Coming Along

The majority (14/20) of young men had no prior knowledge of mindfulness. Just over a third (7/20) signed up to help manage stress, “I knew it was to help with stress and all that, that’s why I came up…” [PM06, Course 1]. Some (4/20) reported they joined at the request of staff in HMYOI; others (2/20) to get out of their cell, or (2/20) simply to occupy their time, “… I didn’t have a work party at that point and I was always locked in; some lad came to my door saying you want to go up to a programme and I said yes…” [PM13, Course 2]. Even at this early stage, several (8/20) did not anticipate completing the course, “I expected that I wasn’t going to last long at this …” [PM03, Course 1].

Experience of the Course

The majority (14/20) initially experienced the course as ‘funny,’ ‘strange,’ or ‘weird,’ and felt embarrassment (12/20), a reaction also noted by the mindfulness teacher. However, over time, increased awareness of a mind and body connection began to show, often as a pleasant surprise:

… pretend you’re breathing in through your legs and all that stuff and you start to feel pure calm and all that and you actually imagine as if you’re doing that … it just shows what the brain can do for you … [PM06, Course 1]

The young men found the breathing techniques and body scan the most useful. The sitting breathing practice was identified by the majority (14/20) as most helpful for dealing with challenging experiences and uncomfortable emotional states:

It was after I heard bad news [his friend had died from illicit drug use] I was just looking for an excuse to go off my nut, and then I could actually feel it like right there, what I’m feeling, and I was like that right just calm down now because I’m going to end up getting in a downer, and then I just like in two minutes just a wee breather and that cleared my head [PM17, Course 3]

Another young man spoke about being able to detach from anger-fuelled urges to strike out, instead tuning-in to his breathing:

I was able to channel it [anger] into breathing, instead of ending up getting into bother through like hitting somebody or trashing myself. I just sat on the edge of my bed with my hands on my lap and I just kind of like kept my back straight, deep breaths in and deep breaths out … [PM27, Course 4]

The body scan was mainly identified as relaxing, “… it was weird because it felt as if you had a quick sleep and that … you felt like rested.” [PM27, Course 4]. However, the young men were also challenged by this practice, expressing difficulty with maintaining attention and stillness, “… they [body scans] were a lot harder … to keep concentration, not fidgeting and pure obviously stay still … and you want to move and that …” [PM35, Course 5]; others found the length of the practice difficult. Confinement in prison was, unsurprisingly, a source of distress. The young men commented on how the mindfulness practices (breathing techniques and body scan) helped buffer against this, “… especially in this kind of situation when we’re behind four walls and like frustration and just keep calm basically in a situation like that” [PM30, Course 4].

Most (13/20) appreciated being part of a group. The importance of group cohesion and connectedness was clear. Feeling safe enhanced this sense of cohesiveness and connection; “it’s going to sound kind of cheesy but it felt like I was safe when I was coming to these mindfulness classes because I was safe from all the thoughts when I come here” [PM03, Course 1], “I can let my guard down now in the group a bit more and be more feeling and that.” [PM17, Course 3].

However, every group was different and on occasions, certain individuals had to be excluded before cohesiveness could be established. Most reported initially finding it hard to concentrate due to disruptive tendencies in others.

Effects of the Course

Those who completed all or most of the course (n = 16) described a range of positive changes, varying from subtle shifts in awareness, to more obvious alterations in behavior. Many (14/16) said that they were sleeping better, feeling better, having better relationships, and felt better able to manage anger and stress. Some of these reported benefits were corroborated in reports from prison staff, and were also noted by the mindfulness teacher, “… helps the guys sleep better, helps them to be more calm, helps them regulate their behavior better … even little inklings that they start to think about life in a slightly different way …” [Mindfulness teacher].

Future Use

Most young men (11/16) reported that they hoped to sustain their mindfulness practice when released back into the community. Perceived obstacles included boredom, lack of time, and discipline, as well as the practices not being familiar to their friends, family, or local community. Several participants emphasized the importance of commitment and perseverance if change was to be achieved and maintained. Some young men (6/16) were hoping that it would help them to desist from further offending behavior:

… it [mindfulness] might help me out there if I stick to it, if I don’t stick to it man it might not help but I'm going to try and stick to it when I'm out there so I don’t come back to prison. [PM29, Course 4]

Discussion

This study explored the feasibility of recruitment and retention to an adapted MBI for incarcerated young men, evaluated potential effectiveness, and assessed acceptability and accessibility. Although recruitment and retention were challenging throughout, data collection was feasible at baseline and post-course. Improvements were recorded in impulsivity, mental wellbeing, inner resilience, and mindfulness. Other positive experiences included better sleep, less stress, more relaxation, feeling more in control, and improved relationships. The ‘body scan’ and ‘breathing techniques’ were reported as being the most helpful techniques. Most hoped to sustain mindfulness practices on release.

Poor MBI attendance and high dropout rates are common in incarcerated populations (range 60–90%) (Simpson et al. 2018). The transient and unpredictable nature of prison life, where inmates are frequently moved or released, lack of suitable spaces for delivering courses, and general security considerations/restrictions feature prominently (Shonin et al. 2013). Qualitative synthesis suggests that addressing participant expectations early on can improve understanding regarding the purpose of mindfulness training and improve subsequent engagement (Wyatt et al. 2014). However, our attempts at this did not lead to improved engagement.

In this current study, contextual, organizational, and logistical issues added to the recruitment and retention challenge. In keeping with our findings, other studies have reported staff ‘buy-in’ and support as crucial in ensuring participant retention (Carroll 1997; Nicholson et al. 2011). Jee et al. (2015) also found, as we did, that a perceived focus on mental health stigmatized views and negatively affected recruitment in delivering MBSR to traumatized young people in care. Other factors include the challenge of integrating Eastern meditative practices into Western culture (Howells et al. 2010). Specific competencies and training may also be required for facilitators to deliver courses effectively in the prison context (Shonin et al. 2013).

In terms of potential effectiveness, impulsivity reduced significantly following MBI training in this study, and others have reported similar benefit in comparable populations (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein 2011; Murphy 1995). Using an MBSR derivative (Mind Body Awareness—MBA) in a young offender institute, Himelstein (2011) reported a significant decrease in impulsivity on the TCS post-intervention (ES 0.43; p < 0.01). However, Barnert et al. (2014) (n = 29), also using MBA, found only small and non-significant improvements (ES 0.20; p = 0.30).

In the current study, significant improvements in mental wellbeing were evident. Other MBI studies in incarcerated populations have demonstrated significantly reduced anxiety (Chandiramani et al. 1998), stress (Himelstein et al. 2012; Perkins 1998), and depression (Chandiramani et al. 1998; Lee et al. 2010). However, only Himelstein et al. (2012) and Flinton (1998) demonstrated these changes in incarcerated young men.

Mindfulness improved significantly on the CAMM (which was designed for adolescents), but not the MAAS in the current study. Two previous MBI studies in incarcerated young men, both using MBA, measured mindfulness using the MAAS (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2012). Neither noted significant improvements.

Only one aspect of inner resilience (‘meaningfulness’) improved significantly in the current study. However, our qualitative findings resonated with the notion of improved meaningfulness. Chandiramani et al. (1998) reported prisoners (age and gender not specified) describing greater hope, wellbeing, and lowered helplessness following a Vipassana intervention, with benefits persisting at 6-month follow-up. Among adult female prisoners receiving a MBI, Sumter et al. (2009) noted participants to be more ‘hopeful’ about the future compared to controls (Sumter, Monk-Turner, and Turner 2009).

Other studies have examined the experiences of incarcerated young men taking part in a MBI. Himelstein (2011) investigated the use of MBA among male adolescents (n = 32; age range 14–18). From short (10 min) semi-structured interviews, four main themes were described: (1) increased wellbeing, (2) improved self-regulation, (3) increased self-awareness, and (4) an accepting attitude towards the course. These are broadly similar to participant reports in the current study. In a separate study, Himelstein et al. (2012) reported openness and an accepting attitude towards the mindfulness course among the young men taking part. This is, somewhat, in contrast with a general lack of such positive reports in the current study, although as the initial perceived ‘strangeness’ diminished, some young men did voice a more accepting attitude.

Barnert et al. (2014) studied MBA in incarcerated young men (n = 29), aged 14–18, finding six major themes (1) enhanced wellbeing, (2) expanded self-awareness, (3) increased self-discipline, (4) resistance to meditation, (5) increased social cohesiveness, and (6) future meditation practice. As in the current study, breath awareness was described as particularly helpful for dealing with stress. The young men in Barnert et al. (2014) also described a newfound ability to walk away from confrontation following the MBA training, a similar finding voiced by some of the young men in our study.

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations include a small sample size, lack of a control group, lack of randomization, and a lack of longer-term outcomes. Monitoring of intervention fidelity was not possible, as each course was adapted to meet participant needs. On the advice of the prison staff, the self-report measures in this study were collected in a group format. However, a group setting can lead to distraction, may inhibit some participants, or may encourage some participants to copy each other. As noted by Shonin et al. (2013), another consideration is risk of recall bias and/or deliberate under- or over-reporting in prison settings. Behavioral measures (e.g., staff reports of prison records of infractions, or recidivism numbers) were beyond the scope of the present study.

Adopting a flexible approach to intervention development to improve acceptability and accessibility for the young men is in keeping with best practice recommendations (Craig et al. 2008; McNeill et al. 2012) and was a strength in this study.

Despite the challenges faced, the findings from our work suggest that mindfulness training may help young people who offend by reducing impulsivity, improving mental wellbeing, and promoting aspects of inner resilience. However, further research is required to optimize recruitment and retention, gather longer-term outcomes, and test the effectiveness of MBI compared with other approaches, ideally in a powered definitive RCT.

References

Abram, K. M., Teplin, L. A., Charles, D. R., Longworth, S. L., McClelland, G. M., & Dulcan, M. K. (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 403–410.

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17, 19–52.

Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-bass.

Arain, M., Campbell, M. J., Cooper, C. L., & Lancaster, G. A. (2010). What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. British Medical Council Medical Research Methodology, 10(1), 67.

Audit Scotland. (2012). Reducing reoffending in Scotland. Scotland: Author.

Barnert, E. S., Himelstein, S., Herbert, S., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Chamberlain, L. J. (2014). Exploring an intensive meditation intervention for incarcerated youth. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 19(1), 69–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12019.

Biegel, G. M., Brown, K. W., Shapiro, S. L., & Schubert, C. M. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for the treatment of adolescent psychiatric outpatients: a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 855-866.

Bosworth, K., & Espelage, D. (1995). Teen conflict survey. Bloomington, IN: Center for Adolescent Studies, Indiana University.

Britton, W. B., Lepp, N. E., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Fisher, N. E., & Gold, J. S. (2014). A randomized controlled pilot trial of classroom-based mindfulness meditation compared to an active control condition in sixth-grade children. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 263–278.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Byrne, S. (2017). The development and evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention for incarcerated young men (Doctoral dissertation, University of Glasgow).

Callaghan, J., Pace, F., Young, B., & Vostanis, P. (2003). Primary mental health workers within youth offending teams: a new service model. Journal of Adolescence, 26(2), 185–199.

Carroll, K. M. (1997). Enhancing retention in clinical trials of psychosocial treatments: practical strategies. Beyond the therapeutic alliance: Keeping the drug-dependent individual in treatment, 165, 4–24.

Carswell, K., Maughan, B., Davis, H., Davenport, F., & Goddard, N. (2004). The psychosocial needs of young offenders and adolescents from an inner city area. Journal of Adolescence, 27(4), 415–428.

Chandiramani, K., Verma, S. K., & Dhar, P. L. (1998). Psychological effects of Vipassana on Tihar Jail inmates. Retrieved from https://www.vridhamma.org/research/Psychological-Effects-of-Vipassana-on-Tihar-Jail-Inmates

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2010). A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychological Medicine, 40(8), 1239–1252. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291709991747.

Chitsabesan, L., Kroll, L., Bailey, S., Kenning, S., & Mac Donald, W. (2006). Mental health needs of young offenders in custody and in the community. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188, 534–540.

Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. British Mesical Journal, 337, a1655.

De Vibe, M., Bjørndal, A., Tipton, E., Hammerstrøm, K. T., & Kowalski, K. (2012). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR) for improving health, quality of life, and social functioning in adults. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 8(3), 127. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2012.3.

Dodge, K., & Pettit, G. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371.

Eriksson, M., & Lindström, B. (2005). Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(6), 460–466.

Farrington, D. P. (2003). What has been learned from self-reports about criminal careers and the causes of offending. London: Home Office.

Fjorback, L. O., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, E., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119.

Flinton, C. A. (1998). The effects of meditation techniques on anxiety and locus of control in juvenile delinquents. (59), ProQuest Information & Learning, US. Available from EBSCOhost psyh database.

Goldberg, D. P. (1988). User’s guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, Berks: NFER-Nelson.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368.

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54.

Greco, L. A., Baer, R. A., & Smith, G. T. (2011). Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the child and adolescent mindfulness measure (CAMM). Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 606.

Greenberg, M. T., & Harris, A. R. (2012). Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: current state of research. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 161–166.

Grossman, P., Niemann, L., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 57(1), 35–43.

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12.

Himelstein, S. (2011). Mindfulness-based substance abuse treatment for incarated youth: a mixed method pilot study. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 30(1), 2–10.

Himelstein, S., Hastings, A., Shapiro, S., & Heery, M. (2012). Mindfulness training for self-regulation and stress with incarcerated youth: a pilot study. Probation Journal, 59(2), 151–165.

Hölzel, B. K., Lazar, S. W., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(6), 537–559.

Howells, K., Tennant, A., Day, A., & Elmer, R. (2010). Mindfulness in forensic mental health: does it have a role? Mindfulness, 1, 4–9.

Jackson, C. (2007). The general health questionnaire. Occupational Medicine, 57(1), 79–79.

Jee, S. H., Couderc, J.-P., Swanson, D., Gallegos, A., Hilliard, C., Blumkin, A., et al. (2015). A pilot randomized trial teaching mindfulness-based stress reduction to traumatized youth in foster care. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 21(3), 201–209.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47.

Kincaid, J. P., Fishburne Jr, R. P., Rogers, R. L., & Chissom, B. S. (1975). Derivation of new readability formulas (automated readability index, fog count and flesch reading ease formula) for navy enlisted personnel.

Kuyken, W., Hayes, R., Barrett, B., Byng, R., Dalgleish, T., Kessler, D., et al. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 386(9988), 63–73.

Lao, S.-A., Kissane, D., & Meadows, G. (2016). Cognitive effects of MBSR/MBCT: a systematic review of neuropsychological outcomes. Consciousness and Cognition, 45, 109–123.

Lee, K. H., Bowen, S., & An-Fu, B. A. I. (2011). Psychosocial outcomes of mindfulness-based relapse prevention in incarcerated substance abusers in Taiwan: a preliminary study. Journal of Substance Use, 16(6), 476–483.

Lipsey, M. (1995). What do we learn from 400 research studies on the effectiveness of treatment with juvenile delingquents? In J. McGuire (Ed.), What works: reducing reoffending (pp. 63–78). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Lösel, F. (1995). Increasing consensus in the evaluation of offender rehabilitation? Lessons from recent research syntheses. Psychology, Crime & Law, 2, 19–39.

McNeill, F. (2006). A desistance paradigm for offender management. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 6(1), 39–62.

McNeill, F., Farrall, S., Lightowler, C., & Maruna, S. (2012). How and why people stop offending: discovering desistance. Insights: Evidence summary to support social services in Scotland No. 15.

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2009). Trajectories of antisocial behavior and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1654.

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2013). Psychosocial (im) maturity from adolescence to early adulthood: distinguishing between adolescence-limited and persisting antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4pt1), 1093–1105.

Murphy, R. (1995). The effects of mindfulness meditation vs progressive relaxation training on stress egocentrism anger and impulsiveness among inmates. (55), ProQuest Information & Learning, US.

Nicholson, L. M., Schwirian, P. M., Klein, E. G., Skybo, T., Murray-Johnson, L., Eneli, I., et al. (2011). Recruitment and retention strategies in longitudinal clinical studies with low-income populations. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 32(3), 353–362.

Ou, S. R., & Reynolds, A. J. (2010). Childhood predictors of male adult crime. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(8), 1097–1107.

Park, T., Reilly-Spong, M., & Gross, C. R. (2013). Mindfulness: a systematic review of instruments to measure an emergent patient-reported outcome (PRO). Quality of Life Research, 22(10), 2639–2659.

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(6), 768–774.

Perkins, R. (1998). The efficacy of mindfulness-based techniques in the reduction of stress in a sample of incarcerated women. . (PhD Thesis), Florida State University.

Richie, J., Lewis, J., Nichols, C., & Ormston, R. (2003). Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers. London: SAGE Publications.

Sabol, W. J., West, H. C., & Cooper, M. (2009). Prisoners in 2008. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Sánchez-López, M. D. P., & Dresch, V. (2008). The 12-item general health questionnaire (GHQ-12): reliability, external validity and factor structure in the Spanish population. Psicothema, 20(4), 839–843.

Sapouna, M., Bisset, C., & Conlong, A. M. (2011). What works to reduce reoffending: a summary of the evidence justice analytical services. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

Semple, R. J. (2010). Does mindfulness meditation enhance attention? A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 1(2), 121–130.

Semple, R. J., Lee, J., Rosa, D., & Miller, L. F. (2010). A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 218–229.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Slade, K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Mindfulness and other Buddhist-derived interventions in correctional settings: a systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(3), 365–372.

Sibinga, E. M., Webb, L., Ghazarian, S. R., & Ellen, J. M. (2016). School-based mindfulness instruction: an RCT. Pediatrics, 137(1), e20152532.

Simpson, S., Mercer, S., Simpson, R., Lawrence, M., & Wyke, S. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for young offenders: a scoping review. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1330–1343.

Singleton, N., Meltzer, H., Gatward, R., Coid, J., & Deasy, D. (1998). Psychiatric morbidity among prisoners: summary report. London: Office of National Statistics.

Steinberg, L. (2010). Commentary: a behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 160.

Steinberg, L., Albert, D., Cauffman, E., Banich, M., Graham, S., & Woolard, J. (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1764.

Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Monahan, K. (2015). Psychosocial maturity and desistance from crime in a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justive and Delinquency.

Sumter, M. T., Monk-Turner, E., & Turner, C. (2009). The benefits of meditation practice in the correctional setting. Journal of Correctional Health Care, 15(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078345808326621.

Ward, T., Yates, P. M., & Willis, G. M. (2012). The good lives model and the risk need responsivity model. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811426085.

Weare, K. (2012). Evidence for the impact of mindfulness on children and young people. Retreived from https://mindfulnessinschools.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/MiSP-Research-Summary-2012.pdf.

Whitaker, R. C., Dearth-Wesley, T., Gooze, R. A., Becker, B. D., Gallagher, K. C., & McEwen, B. S. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences, dispositional mindfulness, and adult health. Preventive Medicine, 67, 147–153.

Witkiewitz, K., Bowen, S., Douglas, H., & Hsu, S. H. (2013). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance craving. Addictive Behaviors, 38(2), 1563–1571.

Witkiewitz, Marlatt, G. A., & Walker, D. (2005). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19(3), 211–228.

Wyatt, C., Harper, B., & Weatherhead, S. (2014). The experience of group mindfulness-based interventions for individuals with mental health difficulties: a meta-synthesis. Psychotherapy Research, 24(2), 214–228.

Ziebland, S., & McPherson, A. (2006). Making sense of qualitative data analysis: an introduction with illustrations from DIPEx (personal experiences of health and illness). Medical Education, 40(5), 405–414.

Zoogman, S., Goldberg, S. B., Hoyt, W. T., & Miller, L. (2015). Mindfulness interventions with youth: a meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(2), 290–302.

Funding

This study received funding from the Scottish Government Criminal Justice Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SS: designed and executed the study, assisted with the data analyses, and wrote the paper. SW: collaborated with the design, analyzing the data and writing and editing of the final manuscript. SM: collaborated with the design, analyzing the data and writing and editing of the final manuscript. The research was carried out as part of a PhD thesis by SS at the University of Glasgow (see Byrne 2017). SW and SWM supervised the PhD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

All procedures used were in accordance with the ethical standards of the College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Sciences Ethics Committee, University of Glasgow and the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) Research Access and Ethics Committee (RAEC). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, S., Wyke, S. & Mercer, S.W. Adaptation of a Mindfulness-Based Intervention for Incarcerated Young Men: a Feasibility Study. Mindfulness 10, 1568–1578 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1076-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1076-z