Abstract

Background

The extent of diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is incompletely understood. We aimed to understand the extent of diagnostic delay of IBD in adults and identify associations between patient or healthcare characteristics and length of delay.

Methods

Articles were sourced from EMBASE, Medline and CINAHL from inception to April 2021. Inclusion criteria were adult cohorts (18 ≥ years old) reporting median time periods between onset of symptoms for Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) or IBD (i.e. CD and UC together) and a final diagnosis (diagnostic delay). Narrative synthesis was used to examine the extent of diagnostic delay and characteristics associated with delay. Sensitivity analysis was applied by the removal of outliers.

Results

Thirty-one articles reporting median diagnostic delay for IBD, CD or UC were included. After sensitivity analysis, the majority of IBD studies (7 of 8) reported a median delay of between 2 and 5.3 months. From the studies examining median delay in UC, three-quarters (12 of 16) reported a delay between 2 and 6 months. In contrast, three-quarters of the CD studies (17 of 23) reported a delay of between 2 and 12 months. No characteristic had been examined enough to understand their role in diagnostic delay in these populations.

Conclusions

This systematic review provides robust insight into the extent of diagnostic delay in IBD and suggests further intervention is needed to reduce delay in CD particularly. Furthermore, our findings provide a benchmark value range for diagnostic delay, which such future work can be measured against.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory condition affecting the gastrointestinal tract, the most prevalent examples being Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [1]. Approximately 6.8 million cases of IBD were reported globally in 2017, with nearly a quarter of these cases in North America, resulting in a significant personal and societal burden [2].

The clinical presentation of IBD is variable, but can include change in bowel habit, rectal bleeding, fatigue and weight loss [3]. In addition, approximately 25% to 40% of individuals with IBD display extraintestinal manifestations, which include arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, uveitis, erythema nodosum and primary sclerosing cholangitis [4]. The range of such presenting symptoms can make it challenging for clinicians to promptly identify patients with IBD, and symptoms can be attributed to other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, all of which can lead to diagnostic delay [5]. Such delays may be further contributed to by factors such as patient demographics, geographical location and the presence of extraintestinal manifestations [6,7,8,9]. For example, in affected countries, symptoms of IBD may be mistaken for abdominal tuberculosis [10]. In cases of diagnostic delay, adverse impacts on clinical outcomes can occur, including an increased need for subsequent surgical intervention and poor response to medical therapy [11, 12].

Recent reports suggest the average diagnostic delay of IBD can range anywhere from 2 months to 8 years [5, 13] and that delays in the diagnosis of CD are longer than for UC [6, 12, 14]. This wide variation reported in the differences in the delay experienced by patients, means the true extent of the problem of delay remains unclear. The aim of this systematic review was to provide a clearer benchmark range for the extent of diagnostic delay, as well as providing information on any characteristics that may be associated with delay.

Methods

Data sources and searches

We conducted a systematic review by searching the medical literature databases of Medline, EMBASE and CINAHL from their inception to April 2021, using a combination of free-text and medical subject headings (MeSH) terms, or equivalents from each database (Supplementary Table 1). Search terms were devised for IBD and diagnostic delay using existing systematic reviews that explored other aspects of IBD, and reviews investigating diagnostic delay in other long-term conditions [15,16,17]. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed during the completion of this systematic review and the protocol was logged with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (registration number: CRD42018108886).

Study selection

The inclusion criteria were developed using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) framework [18]. The included populations were adults aged 18 years or older with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD, CD or UC. Studies with adult populations which included a proportion of participants under 18 years old were retained if the mean age implied the population was largely formed from participants above 18 years old. Studies also had to include the primary outcome of interest, a reported average time period of diagnostic delay for IBD, CD or UC from symptom onset to final diagnosis.

Studies were excluded if they examined delay, but did not report data related to the extent of, or a characteristic related to, the time period of diagnostic delay (i.e. defined as wrong outcomes) or their design included case studies or case series with less than ten participants, literature reviews, systematic reviews or conference abstracts. There were no restrictions on time of publication, as databases were searched from inception. Articles in languages other than English were included, individuals who spoke the language were then requested to make initial assessments and then, if necessary, quality appraise and extract pertinent data, with Google Translate also being used if necessary.

Once the database searches had been undertaken using the reported criteria, the reference manager software Mendeley was used to remove duplicates (Version 1.16.1, Mendeley Ltd., London, UK). The authors E. C. and J. A. P. then completed an independent title and abstract review of 50% of the initially identified articles each. Articles that progressed to abstract review underwent a second review, where E. C. reviewed the abstracts initially reviewed by J. A. P. and vice versa. These included abstracts then underwent a full-text review, with E. C. independently reviewing all full texts and the remaining three authors (J. A. P., B. S., A. D. F.) reviewing a proportion of full texts each. Throughout the review process, disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and by consulting an arbitrating author (BS).

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction of included articles was completed by two reviewers (E. C., J. A. P.). The primary outcome of interest extracted was the reported average time period of diagnostic delay of IBD (for articles that did not distinguish between CD and UC), CD or UC, from symptom onset to diagnosis. Average data regarding diagnostic delay could be reported as mean or median values, with both being recorded along with their accompanying estimate of accuracy (standard deviation or interquartile range respectively). However, due to the typical non-normality of mean diagnostic delay data, only median values were used in this analysis [19]. This allowed for data which was more representative of the average delay actually experienced by patient samples, though removed the possibility to pool data from all included articles using meta-analysis techniques. The unit of time that articles used to report diagnostic delay varied from days to years; therefore, delay data were converted into months to allow comparability of the data.

Additional data extracted included lead author, year of publication, time period of participant recruitment, gender, country and mean sample age. Finally, information (where reported) on any specific characteristics (e.g. demographics, symptoms) and their association with reported diagnostic delay were identified in the articles and extracted. Regarding this characteristic data, no restriction was placed on the measure of central tendency here, but rather the focus was on whether differences in delay were experienced across comparator samples (i.e. extent of diagnostic delay in males vs. females). The data from the included articles were examined using narrative synthesis. In the instance of outlier data, sensitivity analysis was performed, resulting in the exclusion of related studies.

Quality appraisal

A modified Newcastle–Ottawa Score (NOS) was used for quality appraising the included articles, carried out by E. C. and J. A. P. An adapted version of the NOS for cohort studies and for cross-sectional studies were used [20]. The ‘Selection of participants’ and ‘Measurement of outcome’ were the two criteria of the NOS used to assess quality of articles. The representativeness of studies was assessed based on the geographical spread of recruitment, as well as variation in population characteristics.

Results

Search results

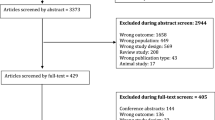

A total of 10,119 unique articles were identified from the three selected databases and underwent title review. Following the exclusion of 6746 articles based upon title, 3373 articles underwent abstract review. From these, 429 articles were reviewed in full, leaving a final 31 articles that reported median data to be included for narrative synthesis (see PRISMA flowchart, below [Fig. 1]).

Study characteristics

Of the 31 articles included in the review, 23 were cohort studies, of which 12 were retrospective [6, 12,13,14, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], eight were prospective cohorts [9, 29,30,31,32,33,34,35] and three combined both methods [36,37,38]. Eight articles used a cross-sectional study design [5, 7, 8, 11, 39,40,41,42]. Nineteen studies were conducted in Europe, seven in Asia, four in North America and one in South America. Twenty articles were based in primary or secondary care, four in tertiary care and five from population registries. Two articles did not report the source from which the sample was drawn.

The majority of articles typically documented the criteria used to diagnose IBD in participants, as a combination of clinical features, radiologic and histologic findings. Formal diagnostic criteria used by articles included Lennard–Jones, European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) and Copenhagen diagnostic criteria. Nine articles did not outline the use of any diagnostic criteria. The characteristics of each study included in the review have been summarized in Table 1.

Quality appraisal

Of the 23 cohort studies, eleven articles were deemed to be ‘truly representative’, 11 ‘somewhat representative’ and one sampled from a ‘selected group of users’. For the eight cross-sectional studies, four articles were ‘truly representative’, three ‘somewhat representative’, one sampled from a ‘selected group of users’ and one ‘did not report the sampling strategy’. Ascertainment of exposure (i.e. diagnosis of IBD) was determined by assessing ‘secure records’ in all cohort studies. For the eight cross-sectional studies, three studies used a ‘validated measurement tool’ to ascertain exposure, in three studies a ‘tool was available and described’ and two studies provided ‘no description’ of how participants with IBD were identified. Assessment of outcome, which in this systematic review was diagnostic delay, was done by ‘record linkage’ in 17 cohort studies and the remaining six by ‘self-report’. Two cross-sectional studies used ‘record linkage’, four used ‘self-reporting’ and two studies provided ‘no description’ for the assessment of outcome (Supplementary Table 2).

Extent of diagnostic delay

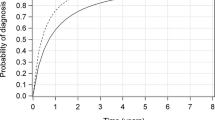

There were 11,597 participants providing median data related to IBD, with 4269 participants originating from studies that did not distinguish between CD or UC. A total of 13,998 participants provided data related to CD and 12,895 provided data relating to UC. Median values of diagnostic delay of IBD were provided by nine articles and ranged from 2 to 96 months. Median delay of CD was provided by 24 articles, ranging from 2 to 84 months and 17 articles reported median delays of 2 to 114 months from initial symptoms to final diagnosis of UC (Table 2).

Through the sensitivity analysis, one article was excluded due to consistently being an outlier across the three condition groups. Burgmann et al. [5] reported median delays of approximately 60–75 months longer than the next closest study across the three analyses. After exclusion of this outlier, the median diagnostic delay of IBD across the remaining eight articles ranged from 2 to 13 months, with three-quarters of these reporting a delay of between 2–5.3 months. Of the 23 studies defining samples solely by CD, the overall delay ranged from 2 to 26.4 months, with three-quarters of the reported median delays ranging from 2 to 12 months. Finally, from the 16 studies examining UC, median diagnostic delay ranged from 2 to 55.2 months, with three-quarter of studies reporting delay between 2 to 6 months. This overall longer median delay observed in patients with CD compared to UC was also mirrored in the subset of studies where delay had been directly compared between the two conditions within the same populations [5, 7, 13, 21, 23, 34]. Finally, when data for each disease category was arranged by year of publication, the extent of delay remained relatively consistent over time from 2009 to 2021 for IBD and UC. However, for the same time period, CD publications showed greater fluctuations year-on-year in reported extent of delay.

Factors associated with diagnostic delay

Three studies compared differences in delay related to help-seeking (from symptom onset to primary health care consultation) and that which occurred after the first consultation. Though Vavricka found that delay was significantly greater for CD than UC patients during the help-seeking and first consultation phase, Nguyen only found delay after first consultation to final diagnosis to be significantly greater for CD patients compared to UC patients [6, 14]. Walker et al. [28] reported longer delays across help-seeking, primary care and secondary care in CD over UC (Table 3). Three articles found statistical significance between increasing age and longer diagnostic delay [8, 25, 30]. The study by Foxworthy and Wilson was the only one that reported median values, showing a statistically significant difference in diagnostic delay of CD between patients over 60 (diagnostic delay 16 months) and patients less than 60 years old at diagnosis (diagnostic delay 5 months) [30].

A prospective cohort study conducted by Burisch et al. grouped data from 14 Western and 8 Eastern European countries to compare differences in diagnostic delay [9]. For CD, median values of diagnostic delay were 4.6 and 3.4 months, respectively, for Western and Eastern Europe. Diagnostic delay was 2.5 and 2.2 months for UC in Western and Eastern Europe respectively. However, these differences were not statistically different. Finally, Pellino et al. stratified patients with CD by disease behavior and found that only patients receiving a diagnosis of penetrating disease had significantly longer delay compared with other disease behaviors which were non-penetrating (p = 0.003) [11] (Table 4).

Discussion

This systematic review demonstrates that receiving a prompt diagnosis of IBD remains difficult to achieve, with patients typically experiencing several months of diagnostic delay. In particular, delay is prolonged in patients with CD compared to UC, with the majority of previous studies reporting diagnostic delay less than 12 months for CD, but less than 6 months for UC. Ultimately, these more specific median delay data ranges provide a new benchmark against which interventions to reduce delay in patients with IBD can be compared. However, research examining the specific factors contributing to delay in IBD remains limited and requires further examination to determine any consistent influence.

The skewed nature of diagnostic delay data means that (for the majority) of patients with CD diagnosis is achieved within a year of symptom onset, with three-quarter of patients with UC diagnosed in < 6 months. However, across CD studies in particular, there remains a substantial proportion (one in four studies) where on average, receiving a final diagnosis of CD could take between 12 to 24 months from the initial onset of symptoms. These findings provide a more accurate understanding of the true extent of diagnostic delay and though not intended to minimise the problem of diagnostic delay in UC, the greatest impact in a reduction in delay for patients with IBD may come from focusing on CD.

Though some degree of interval time period between symptom onset and final diagnosis is inevitable and each country must work within its own practical parameters, we believe that delays of less than 6 months or 12 months for all, not just the majority of, UC and CD patients respectively should be strived for. This should certainly be the case for more advanced healthcare systems, such as the UK, where there remains a minority of patients at the extremes who experience excessive delay, as represented by the interquartile ranges (IQR) by Walker et al. (CD 7.6 months median delay [IQR 3.1–15.0]; UC 3.3 months [1.9–7.3]) [28].

Our reported findings are based on the studies included in the sensitivity analysis, rather than all identified studies. By removing the study by Burgmann et al. [5] which reported extremely protracted delays in IBD, CD and UC diagnosis, we have provided a more representative median range for diagnostic delay. Though removal of such outliers is a somewhat arbitrary one, performing this practical sensitivity analysis enabled us to look at the most common length of delay. To support the removal of studies based on their reported, extreme delay values, we examined the details of the study design, but could not identify any clear reason why their data was drastically different to that of the other studies in the systematic review. However, it was of note that this excluded study reported longer diagnostic delay in UC compared to CD, contrary to other included studies.

Possible reasons for UC consistently demonstrating shorter diagnostic delays than CD could be because the location of disease is confined to the large bowel and patients experiencing rectal bleeding may be more likely to present to a doctor [7]. However, CD delays may be longer due to a lack of clinical suspicion and diagnostic testing, associating common CD symptoms like abdominal pain with other conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome and difficulties in identifying disease that is only present in the small bowel [12, 14, 40].

Though the 26 articles which reported overall diagnostic delay were published between 1971 and 2021, the majority was published after 2006 (80%). For the IBD, CD and UC categories, there was no trend of diagnostic delay over this 15-year time period, though the values for IBD and UC were more consistent from 2009 onwards than for CD. However, inherent variations in country demographics, healthcare systems and study designs make such trends difficult to interpret and studies across multiple years in the same countries are needed to examine changes over time in patient delays.

Though overall diagnostic delay in patients with IBD, CD or UC has frequently been reported in the literature, there remains limited data to have examined the role of specific patient or healthcare factors in their impact to the extent of delay experienced. Such sub-analysis has proven useful in other systematic reviews into diagnostic delay, as this provides focus on certain characteristics which could prove to be avenues to reduce delay. For example, a previous systematic review on diagnostic delay in giant cell arteritis found delay was greater in those patients who did not experience cranial symptoms compared to those with cranial symptoms [16]. However, the most frequently examined characteristic we were able to identify was age, and though these studies found delay to be greater in the older of each dichotomized group, there were only three studies, of which two are nearly 40 years old. More studies, of a consistent and repeated design, are needed to make a stronger case for the role of impact of individual characteristics on the extent of diagnostic delay.

Though not reporting the extent of delay associated with a specific characteristic as per our study design, several studies did highlight other characteristics which were considered to have a significant role on delay. Vavricka et al. found that of adults categorized as experiencing ‘longer’ diagnostic delay (CD > 24 months and in UC > 12 months), those aged < 40 years compared to those > 40 years (in contrast to our findings) and who had ileal disease compared colon disease were significantly more likely to experience this prolonged delay [6]. Novacek et al. found ‘greater age’ at diagnosis to be a risk factor for delayed diagnosis in CD as well as in UC. They also found a higher educational level to be a risk factor in patients with CD, but not in UC [7]. Finally, Lee et al. [12] found an association between patients with CD and defined as experiencing ‘long’ diagnostic delay (defined as ≥ 21.4 months and 6.2 months in CD and UC, respectively) and perianal discomfort. The select nature of these samples (e.g. those with ‘long’ delay) make comparison with our own included data difficult.

Diagnostic delay has been explored in many other studies for a variety of conditions, including giant cell arteritis, gynecological cancers and tuberculosis [16, 43, 44]. Exploring the extent of diagnostic delay in medical conditions, where delays are common, is important as it provides a backdrop for future research examining the reasons for prolonged diagnostic delay and potentially inform interventions for reducing delays and improving patient care. As prolonged diagnostic delay of IBD appears to increase the likelihood of complicated disease, reducing delays in IBD diagnosis could improve the clinical outcome of patients with the condition [12, 45]. The specific use of the fecal calprotectin test was not discussed in the studies of this systematic review. It detects levels of calprotectin within stool as a consequence of neutrophil aggregation to the gastrointestinal tract due to active inflammation like that found in IBD [46]. Existing research suggests that this is effective at differentiating between organic and functional origins of bowel disease, thus could reduce delays in IBD diagnosis [47, 48].

The focus on median data within the analysis in this systematic review is a key strength as it reduces problems related to overestimation of averages typically related to use of means from skewed data, providing a more robust estimate of diagnostic delay. Furthermore, as well as examining IBD overall, this systematic review examined the most common disease sub-categories of UC and CD, and, finally, we did not restrict study inclusion based on language, leading to additional studies being included in the review. A limitation of this study is the variation between individual study designs, for instance differences in participant age, method of IBD diagnosis and country. However, despite the introduction of such heterogeneity, this data also provides a fuller picture of the problem of diagnostic delay in this disease group.

In conclusion, this systematic review provides a robust insight into the current extent of diagnostic delay in IBD, indicating that diagnostic delay remains a pertinent issue for patients with IBD, particularly CD, but that the factors which may have a role in delay remain unclear. This systematic review provides a backdrop and benchmark onto which further research can be conducted to reduce the time to IBD diagnosis, particularly exploring knowledge of IBD amongst healthcare professionals and the general population to help reduce overall delay. This future research is particularly important, as reducing diagnostic delay of IBD may improve the clinical course of the disease.

References

Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1053–60.

GBD 2017 Inflammatory Bowel Disease Collaborators. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroent Hepatol. 2020;5:17–30.

Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, et al. Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2011;60:571–607.

Levine JS, Burakoff R. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2011;7:235–41.

Burgmann T, Clara I, Graff L, et al. The Manitoba inflammatory bowel disease cohort study: prolonged symptoms before diagnosis–how much is irritable bowel syndrome? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:614–20.

Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, et al. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:496–505.

Novacek G, Grochenig HP, Haas T, et al. Diagnostic delay in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Austria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2019;131:104–12.

Harper PC, McAuliffe TL, Beeken WL. Crohn’s disease in the elderly a statistical comparison with younger patients matched for sex and duration of disease. Arch Intern MedS. 1986;146:753–5.

Burisch J. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Occurrence, course and prognosis during the first year of disease in a European population-based inception cohort. Dan Med J. 2014;61:B4778.

Das K, Ghoshal UC, Dhali GK, Benjamin J, Ahuja V, Makharia GK. Crohn’s disease in India: a multicenter study from a country where tuberculosis is endemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1099–107.

Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Selvaggi F, Riegler G. Delayed diagnosis is influenced by the clinical pattern of Crohn’s disease and affects treatment outcomes and quality of life in the long term: a cross-sectional study of 361 patients in Southern Italy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:175–81.

Lee DW, Koo JS, Choe JW, et al. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of intestinal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6474–81.

Basaranoglu M, Sayilir A, Demirbag AE, Mathew S, Ala A, Senturk H. Seasonal clustering in inflammatory bowel disease: a single centre experience. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:877–81.

Nguyen VQ, Jiang D, Hoffman SN, et al. Impact of diagnostic delay and associated factors on clinical outcomes in a US inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1825–31.

Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112 Suppl 1:S92.

Prior JA, Ranjbar H, Belcher J, et al. Diagnostic delay for giant cell arteritis - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2017;15:120.

Ford AC, Bernstein CN, Khan KJ, et al. Glucocorticosteroid therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011; 106:590–9; quiz 600.

Methley AM, Campbell S, Chew-Graham C, McNally R, Cheraghi-Sohi S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: a comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:579.

Sykes MP, Doll H, Sengupta R, Gaffney K. Delay to diagnosis in axial spondyloarthritis: are we improving in the UK? Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:2283–4.

Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154.

Cantoro L, Di Sabatino A, Papi C, et al. The time course of diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease over the last sixty years: an Italian multicentre study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:975–80.

Maconi G, Orlandini L, Asthana AK, et al. The impact of symptoms, irritable bowel syndrome pattern and diagnostic investigations on the diagnostic delay of Crohn’s disease: a prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:646–51.

Szántó K, Nyári T, Bálint A, et al. Biological therapy and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel diseases - data analysis of almost 1000 patients from a Hungarian tertiary IBD center. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200824.

Li Y, Ren J, Wang G, et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with increased rate of abdominal surgery: a retrospective study in Chinese patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:544–8.

Lin WC, Tung CC, Lin HH, et al. Elderly adults with late-onset ulcerative colitis tend to have atypical, milder initial clinical presentations but higher surgical rates and mortality: a Taiwan society of inflammatory bowel disease study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:e95-7.

Banerjee R, Pal P, Girish BG, Reddy DN. Risk factors for diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease and their impact on long-term complications: how do they differ in a tuberculosis endemic region? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:1367–74.

Kang HS, Koo JS, Lee KM, et al. Two-year delay in ulcerative colitis diagnosis is associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha use. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:989–1001.

Walker GJ, Lin S, Chanchlani N, et al. Quality improvement project identifies factors associated with delay in IBD diagnosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:471–80.

Lind E, Fausa O, Elgjo K, Gjone E. Crohn’s disease. Clinical manifestations. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1985;20:665–70.

Foxworthy DM, Wilson JA. Crohn’s disease in the elderly. Prolonged delay in diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1985;33:492–5.

Langholz E, Munkholm P, Nielsen OH, Kreiner S, Binder V. Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in Copenhagen county from 1962 to 1987. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1247–56.

Munkholm P, Langholz E, Nielsen OH, Kreiner S, Binder V. Incidence and prevalence of Crohn’s disease in the county of Copenhagen, 1962–87: a sixfold increase in incidence. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:609–14.

Timmer A, Breuer-Katschinski B, Goebell H. Time trends in the incidence and disease location of Crohn’s disease 1980–1995: a prospective analysis in an urban population in Germany. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 1999;5:79–84.

Romberg-Camps MJ, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Schouten LJ, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in South Limburg (the Netherlands) 1991–2002: incidence, diagnostic delay, and seasonal variations in onset of symptoms. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:115–24.

Chaparro M, Garre A, Núñez Ortiz A, et al. On Behalf Of The EpidemIBD Study Group Of Geteccu. Incidence, clinical characteristics and management of inflammatory bowel disease in Spain: large-scale epidemiological study. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2885. J Clin Med. 2022;11:5816.

Yang SK, Hong WS, Min YI, et al. Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis in the Songpa-Kangdong District, Seoul, Korea, 1986–1997. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1037–42.

Guariso G, Gasparetto M. Visonà Dalla Pozza L, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease developing in paediatric and adult age. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:698–707.

Nahon S, Ramtohul T, Paupard T, Belhassan M, Clair E, Abitbol V. Evolution in clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease over time at diagnosis: a multicenter cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;30:1125–9.

Kyle J. The early diagnosis of chronic Crohn’s disease. Scott Med J. 1971;16:197–201.

Albert JG, Kotsch J, Köstler W, et al. Course of Crohn’s disease prior to establishment of the diagnosis. Z Gastroenterol. 2008;46:187–92.

Irving P, Burisch J, Driscoll R, et al. IBD2020 global forum: results of an international patient survey on quality of care. Intestinal Research. 2018;16:537–45.

Gomes TNF, de Azevedo FS, Argollo M, Miszputen SJ, Ambrogini O Jr. Clinical and demographic profile of inflammatory bowel disease patients in a reference center of Sao Paulo. Brazil. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2021;14:91–102.

Getnet F, Demissie M, Assefa N, Mengistie B, Worku A. Delay in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in low-and middle-income settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17:202.

Williams P, Murchie P, Bond C. Patient and primary care delays in the diagnostic pathway of gynaecological cancers: a systematic review of influencing factors. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e106–11.

Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, et al. Clinical factors and disease course related to diagnostic delay in Korean Crohn’s disease patients: results from the CONNECT Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144390.

Pathirana WGW, Chubb SP, Gillett MJ, Vasikaran SD. Faecal calprotectin. Clin Biochem Rev. 2018;39:77–90.

Schoepfer AM, Trummler M, Seeholzer P, Seibold-Schmid B, Seibold F. Discriminating IBD from IBS: comparison of the test performance of fecal markers, blood leukocytes, CRP, and IBD antibodies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:32–9.

Waugh N, Cummins E, Royle P, et al. Faecal calprotectin testing for differentiating amongst inflammatory and non-inflammatory bowel diseases: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2013, 17:xv–xix, 1–211.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the systematic review team (Dr Nadia Corp and Dr Opeyemi Babatunde) at Keele University School of Medicine for their advice and assistance in the completion of this systematic review. They also wish to thank Dr Kay Polidano who was involved in the translation of selected articles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E. C.: creation of search strategy, database search, data extraction, article review, narrative synthesis, writing of the manuscript. J. A. P.: initial study design, creation of search strategy, data extraction, article review, narrative synthesis, writing of the manuscript. B. S.: initial study design, article review, writing of the manuscript. A. D. F.: initial study design, clinical input, article review, writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

EC, BS, ADF, and JAP declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was performed conforming to the Helsinki declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 and 2008 concerning human and animal rights, and the authors followed the policy concerning informed consent as shown on Springer.com.

Disclaimer

The authors are solely responsible for the data and the contents of the paper. In no way, the Honorary Editor-in-Chief, Editorial Board Members, the Indian Journal of Gastroenterology or the printer/publishers are responsible.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cross, E., Saunders, B., Farmer, A.D. et al. Diagnostic delay in adult inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Indian J Gastroenterol 42, 40–52 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-022-01303-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12664-022-01303-x