Abstract

Postnatal depression (PND) is estimated to affect approximately 17% of mothers, and if left untreated can have negative health consequences, not only for the mother but for the family unit. Homelessness is a multifaceted concept which also has negative health consequences and is often termed a stressful life event. Exploring the literature which links these two factors may promote the implementation of policies which work to address both these health issues. The aim of this scoping review was to determine the breadth and nature of the literature investigating the quantitative relationship between PND and homelessness in women living in high-income countries. Comprehensive searches were performed in June 2020 in MEDLINE, PsychInfo, Embase, Social Policy and Practice and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. Grey literature was also searched, including unpublished studies, dissertations, conference proceedings and reports by the UK charities. Twelve studies met the eligibility criteria. There are few well-controlled longitudinal studies and a high level of variability between studies in terms of the definitions used for homelessness and in the screening tools to detect PND symptoms. Future research would benefit from undertaking waves of prospective data collection, using a well-defined concept of homelessness and implementing validated tools for measuring PND.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Untreated postnatal (postpartum) depression, or PND, is linked to negative maternal health consequences for some mothers, including social relationship problems, addictive behaviours, poorer quality of life and suicidal ideation (Slomian et al., 2019). The environment created by PND may also not be conducive for the optimal development of an infant, with possible adverse outcomes including insecure attachment, behavioural problems and impaired emotional development (Stanley et al., 2004). PND is estimated to affect approximately 17% of mothers (Hahn-Holbrook et al., 2018; Shorey et al., 2018). PND is considered to be a depressive episode which occurs in a specified time frame after birth; ranging from within the first 4 weeks (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) to up to 1 year (Wisner et al., 2010). There is debate on whether PND is a distinct diagnosis, with general diagnostic interview schedules and both general and postnatal specific symptom questionnaires used to identify cases and ascertain severity (Hewitt et al., 2009).

Homelessness is a life event which has been linked to poor health outcomes (Thomson et al., 2013). These health impacts result in rates of morbidity and mortality that are higher in homeless individuals than in the general population (Fazel et al., 2014). Homelessness and ill health are intrinsically linked. Whilst homelessness can result in ill health, ill health can also be a contributary factor for entering a state of homelessness. The relationship between poor mental health and homelessness has been systematically reviewed, showing a positive association between housing insecurity and poor mental health outcomes (Singh et al., 2019). Mental health problems are more prevalent in people who are socioeconomically disadvantaged (McManus et al., 2016). Housing as a key social determinant of mental health may reflect the correlation between housing insecurity and stress, as well as the possible barriers for people without stable residency in accessing primary and secondary mental health services (Perry and Craig, 2015). Housing is a fundamental determinant of health, security of which is directly related to income and social position (Braubach and Fairburn, 2010).

There is no universally accepted definition of homelessness and varying typologies of homelessness reflect the different realities of people without shelter in different regions of the world (United Nations Centre for Human Settlements, 2000). The lower level of social provision in developing countries results in a narrower concept of homelessness, often defined as simply being ‘roofless’. In high-income countries where secure tenure is the norm, the concept of homelessness is often widened, reflective of higher general living standards. The European Federation of National Organisations working with the Homeless (FEANTSA) proposed a definition which incorporates those who are roofless, houseless or living in insecure or inadequate housing (FEANTSA, 2017). This includes those living in threat of eviction, in overnight shelters or refuge accommodation. The lack of consensus on the definition of homelessness in either political or research environments has led to the definition of homelessness in studies being operationalised differently by individual research teams, which can be problematic for describing the extent of the problem (Fitzgerald et al., 2001).

Outside of statutory or organisational bodies’ definition of homelessness, particular emphasis may be placed of homelessness on the concept of ‘home’. Home has a plurality of physical and emotional meanings attached to it (Ravenhill, 2003). For Jackson-Wilson and Borgers, homelessness is a form of alienation from the rest of society, caused by the loss of a bond that links, or connects, the individual with society (1993). This disaffiliation may be a result of a loss in work, home or family links. For women particularly, marital and family instability can lead to a form of societal alienation and feeling of homelessness, irrespective of their economic living situation. Conversely, those with poor living standards may not identify with FEANTSA’s definition of homelessness, as their strong social ties mean that they still identify themselves as having a ‘home’ (Ravenhill, 2003).

Most of the research on homelessness has focused on men who are roofless (Bretherton, 2017). For mothers who perceive themselves as homeless, or are defined by organisations such as FEANSTA as homeless, their lived experience can differ depending on their cultural background. The cultural underpinnings of a society, such as a collective system of values or beliefs, as well as political and economic factors can create vulnerability in individuals (Shier et al., 2011). The lived experiences of women who are homeless may differ depending on public perceptions, societal discrimination and their own ideological values and beliefs. Some mothers have discussed feelings of fear, shame and embarrassment because of their homelessness (Milaney et al., 2017). Some mothers have also cited the needs of their children as first and foremost, whether that be for health, safety or stability. The extent to which homelessness and PND co-occur is relatively unknown (Bretherton, 2017). It is also important to understand whether PND might be a precipitating factor in moving into a state of homelessness for some families, or whether homelessness is more likely to be a risk factor for PND. This type of research requires longitudinal studies. A greater understanding of the pathways into homelessness and its relationship with mental health, along with the potential extent of co-occurrence, might promote the implementation of policies that broach both public health sectors, not just addressing individual problems in isolation to other socioeconomic issues (Mago et al., 2013).

In recognition of the uncertainty of the evidence sources or potential gaps in the knowledge base, we applied a scoping review methodology to establish how much quantitative research existed on this topic, how key concepts were measured and the study designs used. The review was guided by the research question, ‘How has the literature quantitively explored the relationship between PND and homelessness in women in high-income countries?’ and three objectives: 1. To ascertain the extent to which the literature has quantified the nature of the relationship between homelessness and PND; 2. To determine how the outcome of homelessness and PND were measured and analysed and 3. To determine whether there was a possibility of establishing causality through classifying the quantitative study designs employed.

Methods

We used a framework for scoping reviews (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005) and the scoping review reporting framework (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al., 2018).

A comprehensive search strategy was developed in MEDLINE and then adapted for PsychInfo, Embase, Social Policy and Practice and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts electronic databases. This was an iterative process, refining the search strategy based on abstracts retrieved during piloting. The final search was conducted on 17 June 2020. Keywords such as homeless, inadequate housing, insecure housing and postnatal depression were used. Subject headings, synonyms, truncations and boolean operators were used to expand the search. The full search strategy conducted in MEDLINE is found in Appendix 1.

Grey literature was searched through Opengrey, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database, e-thesis online service (EThOS) and databases of relevant UK charities. Grey literature from charities was searched for only in the UK in recognition of the practical difficulties for searching in all high-income countries. Websites of the UK charities that produce reports in the fields of mental health, pregnancy or homelessness were searched (Appendix 2). Reference lists of all included studies were reviewed to locate additional papers. All retrieved studies were downloaded into Endnote (version X9.2) and de-duplicated using this software. The titles and abstracts of retrieved studies were screened by one reviewer for eligibility and the full text of potentially eligible studies obtained. These were then assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by one author. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are found in Table 1. Data were extracted using a charting form which was adapted and expanded from the version proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005). As is usual for this kind of review, quality assessment of the studies was not performed.

Results

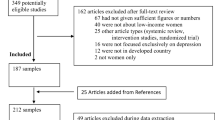

The electronic search strategy yielded a total of 6009 records, and the grey literature and reference list searches yielded 61 records. After deduplication, 3631 records were screened. After screening against eligibility criteria, 12 studies were found to be relevant for this review (see Fig. 1). Included studies were conducted in four high-income countries, the US (8), the UK (2), Australia (1) and Canada (1). All studies analysed observational datasets consisting of large populations, ranging from 2631 to 91,253 women. The mean sample size across the studies was 26,527 women. The general study characteristics are displayed in Table 2.

Definition of PND

Across the studies, six different methods for measuring PND and four different concepts of homelessness were used. The most common method for measuring PND symptoms was the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Core questionnaire (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021), 42%, which asks mothers about their attitude and feelings since giving birth. The six studies which used the PRAMS questionnaire used the same cutoff value to determine depression, women scoring nine or more out of a possible 15 were classed as depressed (Liu et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2017, 2018; Pooler et al., 2013; Qobadi et al., 2016; Salm Ward et al., 2017). Two other studies used a validated scale, the 10-question Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), to measure depressive symptoms (Cox et al., 1987). Dennis et al. (2012) considered scores of 13 or more on the EPDS as depressive symptoms whilst Denckla et al. (2018) did not use a cutoff value as this study aimed to review symptom trajectories. The Millennium Cohort Study analysed by Tunstall et al. (2010) used unvalidated questions, instead asking the mother about feeling low or sad for 2 or more weeks since birth.

In contrast, three methods of measuring PND were used in the included studies which were not specifically designed to measure depressive symptoms in postnatal women or to diagnose PND. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) is a screening tool for depression, used by Pooler et al. (2013), adapted from the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001, 2003). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS), is a self-reported 21 item severity questionnaire, used by Yelland et al. (2010) with scores over 10 characterising depressive symptoms, again not specifically designed for the postnatal period (Lovibond and Lovibond, 1996). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (CIDI-SF) used in two studies was the only measure of PND assessed by a diagnostic interview. The CIDI-SF was designed for large-scale epidemiology studies, it does not require clinical judgement and the long form is considered a ‘gold standard’ in the diagnosis of depression (Kessler et al., 1998). Both studies that used the CIDI-SF defined a major depressive episode as the experience of three or more symptoms of dysphoria or anhedonia (Curtis et al., 2014; Park et al., 2011).

Definition of Homelessness

As defined by FEANTSA, and conceptually theorised by the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements, homelessness in high-income countries incorporates not only those who are roofless or houseless but individuals living in insecure or inadequate housing (FEANTSA, 2017). Nine studies, spanning all four countries, measured homelessness by using a yes/no questionnaire in which homelessness was defined only by the term itself (Denckla et al., 2018; Dennis et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2018; Mukherjee et al., 2017, 2018; Pooler et al., 2013; Qobadi et al., 2016; Salm Ward et al., 2017; Yelland et al., 2010). No other information was provided in these papers on how the authors defined the concept of homelessness to the participant; limiting the understanding of how this term was interpreted by the participants.

Three studies used a more detailed description of homelessness. The study conducted by Curtis et al. (2014), defined homelessness as not having a fixed, regular and adequate night-time residence, or living in a shelter or temporary accommodation. Using this definition incorporates all four domains of FEANTSA’s definition of homelessness. In addition, they measured the imminent risk of homelessness by threat of eviction, which is included in FEANTSA’s definition of homelessness under the conceptual category of an insecure living situation. Tunstall et al. (2010) used the definition of having nowhere permanent to live, which would include those who identify as roofless or houseless. An additional term used and measured in the Tunstall paper was ‘negative movers’, which included those with relationship breakdowns and those who are at threat of housing eviction. Although relational breakdowns are not included in FEANTSA’s definition, it is cited in the literature as a key contributory factor to homelessness (Tischler et al., 2007).

Park et al. (2011) defined homelessness as those living in temporary housing, in a group shelter, abandoned building, on the street or other place not meant for regular housing. This definition meets FEANTSA’s roofless and houseless categories. The Fragile Families and Child Well-being dataset analysed in this study used an extensive questionnaire to evaluate homelessness, enabling a more detailed definition than just ‘homeless’.

Analysis of Multiple Stressful Life Events

Nine studies analysed more than one stressful life event alongside homelessness. In analysing more than one outcome, the researchers employed three different approaches in determining the relationship between homelessness as a stressful life event and PND. Six of the nine studies examined the risk of individual stressors on PND, thereby reporting separate figures on the association of PND and homelessness (Denckla et al., 2018; Dennis et al., 2012; Mukherjee et al., 2018; Pooler et al., 2013; Qobadi et al., 2016; Salm Ward et al., 2017). By measuring more than one outcome associated with PND, this gives the opportunity for authors to control for other stressful life events. Two studies took a cumulative approach by aggregating the number of stressors, regardless of the type, to report the association of an accumulation of reported stressful life events on the risk of PND. Liu et al. (2018) grouped the findings into 1–2 stressors, 3–5 stressors and 6 + stressors. Yelland et al. (2010) aggregated homelessness within 1–2 stressors or 3 + stressors. The final approach, adopted by Mukherjee et al. (2017), was to categorise life events in four domains, including partner-related, traumatic, emotional and financial and to evaluate the effects of these domains on the risk of PND, regardless of the number of stressors in each category. Homelessness was included within the financial category of stressful life events. Although the studies which aggregated homelessness with other stressful life events did not produce results on a direct association between homelessness and PND, as these variables were measured independently from other outcomes, it would be possible to retrieve this figure from the raw data.

The Temporal Sequence of Homelessness and PND

The ability to determine a causal relationship between homelessness and PND is dependent on the study designs employed. Three studies conducted a longitudinal analysis of their datasets. Denckla et al. (2018) used the ALSPAC dataset whilst Curtis et al. (2014) and Park et al. (2011) analysed the Fragile Families and Child Well-being study. Curtis et al. (2014) considered maternal depression in the first wave of data collection at 1-year postpartum and then homelessness in the second wave of data collection at 3 years postpartum. The two data collection points were chosen in order to illustrate any effects of PND on subsequent homelessness. The other two longitudinal studies measured the association between homelessness and PND through observations at different time points. Denckla et al. (2018) used six waves of data collection on depressive symptoms, spanning 5 years after their initial data collection on homelessness status. Park et al. (2011) administered surveys at 1, 3 and 5 years postpartum for PND and 1-year postpartum for homelessness. Both these studies aimed to evaluate a causal inference between homelessness in the perinatal or postnatal period and subsequent depressive symptoms postnatally.

The remaining nine studies used a cross-sectional study design. However, seven of these included studies did consider the sequential order of homelessness and PND by analysing data collected retrospectively over different time periods. Six studies analysed data that asked about stressful life events in the year preceding childbirth. One study analysed stressful life events during pregnancy, whilst depressive symptoms were measured in the postnatal time period. None of the studies analysed whether bi-directionality was possible.

Discussion

In this scoping review, we explored the design of studies that have quantified a relationship between PND and homelessness in women living in high-income countries. Across the 12 included studies, only six different sources of data were reported, collected from four countries. The study design used was predominantly cross-sectional, with only three studies using longitudinal analysis to explore a unidirectional relationship between homelessness and PND. There was a large degree of variation, both in terms of PND measurement methods and definitions of homelessness. The variety of measures available for PND and its symptoms, as well as cutoff values, reflects the variability in concepts of PND adopted by authors and the potential practical limitations for large-scale studies to collect this information.

The geographical spread of included studies was expected. It correlates with a mapping of worldwide research productivity into maternal depression (Brüggmann et al., 2017). It also correlates with a recent global evidence map on homelessness research, which found that the US, the UK, Australia and Canada dominated the field (White et al., 2018).

Singh et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of longitudinal studies to examine the temporal sequence between housing instability and the broader concept of mental health. They concluded that 'prior exposure to housing disadvantage may impact mental health later in life' (p.262). A limitation identified of the studies in Singh’s review was the variability of measures used for housing inequality and mental health, resulting in a large amount of heterogeneity. The methodological limitations identified are similar to the findings of this review. Few of the studies included in this review used a well-defined concept of homelessness, with a poorly detailed definition allowing subjective interpretation of the term by the participant completing the questionnaire. Focusing on a narrower more stereotypical concept of homelessness, as in those living without a roof over their head, underestimates the extent of residential instability.

All 12 studies analysed large observational datasets, either longitudinal or cross-sectional in design, collected for surveillance reasons or as part of large study cohorts. Whilst the majority only used cross-sectional data, seven studies attempted to account for temporality by asking about events retrospectively. Recollecting depression symptoms or homelessness retrospectively, especially over long periods, can result in recall bias. Retrospective recall of depressive symptoms has been shown to be inaccurate when compared to momentary affect reports, with individuals prone to exaggeration of either positive or negative symptoms dependent on their current mental state (Ben-Zeev et al., 2009). The impact of retrospective recall bias on episodes of homelessness is not known.

Strengths and Limitations of this Review

We followed a published scoping review framework and searched a range of databases and grey literature sources across disciplines, using a wide range of key search terms (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005). The included studies in this review were limited to those published in English, which may have resulted in language bias and the exclusion of relevant papers that were published in other languages. All four countries have English as an official language, which may reflect this exclusion criterion. Grey literature from key charities was only searched for in the UK, this means it is likely we will have missed unpublished studies from charities in other high-income countries.

Recommendations for Future Research

This review identified multiple methodological limitations in the current evidence base that elucidates a relationship between PND and homelessness. The definitions of homelessness proved to be largely non-descriptive, with only three studies detailing homelessness beyond the term itself. Future studies may benefit from research materials with a definition of homelessness similar to that proposed by FEANSTA, thereby ensuring that the broad range of living conditions included under the umbrella of homeless is evaluated. There is also a scarcity in longitudinal studies with repeated measures on PND and homelessness, and most data collection on homelessness was done retrospectively. Novel studies going forward may benefit from waves of prospective data collection, enabling temporality between PND and homelessness. The use of structured or semi-structured interviews to establish postnatal depressive symptoms may also remedy the shortcomings of self-reporting measures. However, it is acknowledged that more intensive data collection methods are expensive and potentially unrealistic for large-scale studies, as well as the burden and difficulty of repeated data collections on a demographic of people who have troubled lives and high attrition rates in longitudinal research (Molewyk Doornbos et al., 2020). The use of symptom questionnaires is a more realistic method for large-scale studies, appreciating the likelihood of self-reporting to overestimate the prevalence of depression in the population (Thombs et al., 2018). Future research may also benefit from understanding the impact of retrospective recall bias on episodes of homelessness, and if, therefore, prospective data collection is necessary for accurate self-reporting.

Investigating a relationship between homelessness and PND should be viewed in the context of mothers having a number of other potential underlying economic and social stressors, which are dependent on the society they live in Bina, 2008. In gaining a better understanding of these hierarchal structures, this could assist societies in creating and implementing policies which will effectively identify or manage PND. Future research into PND and homelessness in mothers should be designed in the context of the lived experience of mothers, accepting the different social structures that women reside in.

Conclusion

Research investigating the relationship between PND and homelessness in women from high-income countries has multiple methodological limitations. To more effectively investigate a relationship between PND and homelessness, longitudinal studies with well-defined concepts of homelessness are required.

Data and material availability

All data are presented.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract, 8, 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Ben-Zeev, D., Young, M. A., & Madsen, J. W. (2009). Retrospective recall of affect in clinically depressed individuals and controls. Cognition and Emotion, 23, 1021–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802607937

Bina, R. (2008). The impact of cultural factors upon postpartum depression: A literature review. Health Care for Women International, 29(6), 568–592. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330802089149

Braubach, M., & Fairburn, J. (2010). Social inequities in environmental risks associated with housing and residential location—A review of evidence. European Journal of Public Health, 20, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp221

Bretherton, J. (2017). Reconsidering gender in homelessness. European Journal of Homelessness, 11, 1–22.

Brüggmann, D., Wagner, C., Klingelhöfer, D., et al. (2017). Maternal depression research: Socioeconomic analysis and density-equalizing mapping of the global research architecture. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0669-6

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (2021). PRAMS Questionnaires. https://www.cdc.gov/prams/questionnaire.htm. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item edinburgh postnatal depression scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Curtis, M. A., Corman, H., Noonan, K., & Reichman, N. E. (2014). Maternal depression as a risk factor for family homelessness. American Journal of Public Health, 104, 1664–1670. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301941

Denckla, C. A., Mancini, A. D., Consedine, N. S., et al. (2018). Distinguishing postpartum and antepartum depressive trajectories in a large population-based cohort: The impact of exposure to adversity and offspring gender. Psychological Medicine, 48, 1139–1147. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002549

Dennis, C.-L., Heaman, M., & Vigod, S. (2012). Epidemiology of postpartum depressive symptoms among Canadian women: Regional and national results from a cross-sectional survey. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 57, 537–546. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371205700904

Fazel, S., Geddes, J. R., & Kushel, M. (2014). The health of homeless people in high-income countries: Descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet (London, England), 384, 1529–1540. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61132-6

FEANTSA, (2017). What is ETHOS ? European typology of homelessness. In: Eur. Typology Homelessness Hous. Exclusion. https://www.feantsa.org/en/toolkit/2005/04/01/ethos-typology-on-homelessness-and-housing-exclusion. Accessed 10 Nov 2020

Fitzgerald, S. T., Shelley, M. C., II., & Dail, P. W. (2001). Research on homelessness sources and implications of uncertainty. Am Behav Sci (beverly Hills), 45, 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027640121957051

Hahn-Holbrook, J., Cornwell-Hinrichs, T., & Anaya, I. (2018). Economic and health predictors of national postpartum depression prevalence: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of 291 studies from 56 countries. Front Psychiatry, 8, 248. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00248

Hewitt, C. E., Gilbody, S. M., Brealey, S., et al. (2009). Methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care: An integrated evidence synthesis and value of information analysis. Health Technol Assess (rockv), 13, 1–190. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta13360

Jackson-Wilson, A. G., & Borgers, S. B. (1993). Disaffiliation revisited: A comparison of homeless and nonhomeless women’s perceptions of family of origin and social supports. Sex Roles, 28(7–8), 361–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289602

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Mroczek, D., et al. (1998). The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 7, 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.47

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. W. (2003). The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Medical Care, 41, 1284–1292. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C

Liu, C. H., Phan, J., Yasui, M., & Doan, S. (2018). Prenatal life events, maternal employment, and postpartum depression across a diverse population in New York City. Community Mental Health Journal, 54, 410–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-017-0171-2

Lovibond, S. H., Lovibond, P. F. (1996). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Psychology Foundation of Australia.

Mago, V. K., Morden, H. K., Fritz, C., et al. (2013). Analyzing the impact of social factors on homelessness: A fuzzy cognitive map approach. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 13, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-94

McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., & Brugha, T. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital, Leeds.

Milaney, K., Ramage, K., Fang, X. Y., & Louis, M. (2017). Understanding mothers experiencing homelessness. Homeless Hub.

Molewyk Doornbos, M., Zandee, G. L., Timmermans, B., et al. (2020). Factors impacting attrition of vulnerable women from a longitudinal mental health intervention study. Public Health Nursing, 37, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12687

Mukherjee, S., Coxe, S., Fennie, K., et al. (2017). Antenatal stressful life events and postpartum depressive symptoms in the United States: The role of women’s socioeconomic status indices at the state level. Journal of Women’s Health (Larchmt), 26, 276–285. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2016.5872

Mukherjee, S., Fennie, K., Coxe, S., et al. (2018). Racial and ethnic differences in the relationship between antenatal stressful life events and postpartum depression among women in the United States: does provider communication on perinatal depression minimize the risk? Ethnicity & Health, 23, 542–565. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1280137

Park, J. M., Fertig, A. R., & Metraux, S. (2011). Changes in maternal health and health behaviors as a function of homelessness. Soc Serv Rev, 85, 565–585. https://doi.org/10.1086/663636

Perry, J., & Craig, T. (2015). Homelessness and mental health. Trends in Urolology & Men’s Health, 6, 19–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/tre.445

Pooler, J., Perry, D. F., & Ghandour, R. M. (2013). Prevalence and risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms among women enrolled in WIC. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 17, 1969–1980. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1224-y

Qobadi, M., Collier, C., & Zhang, L. (2016). The effect of stressful life events on postpartum depression: Findings from the 2009–2011 Mississippi pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-016-2028-7

Ravenhill, M.H. (2003) The culture of homelessness: An ethnographic study. PhD thesis, London School of Economics and Political Science (United Kingdom).

Salm Ward, T., Kanu, F. A., & Robb, S. W. (2017). Prevalence of stressful life events during pregnancy and its association with postpartum depressive symptoms. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 20, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0689-2

Shier, M. L., Jones, M. E., & Graham, J. R. (2011). Sociocultural factors to consider when addressing the vulnerability of social service users: Insights from women experiencing homelessness. Affilia, 26, 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109911428262

Shorey, S., Chee, C. Y. I., Ng, E. D., et al. (2018). Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 104, 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.08.001

Singh, A., Daniel, L., Baker, E., & Bentley, R. (2019). Housing disadvantage and poor mental health: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 57, 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2019.03.018

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., et al. (2019). Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Women’s Health (London, England), 15, 1745506519844044–1745506519844044. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044

Stanley, C., Murray, L., & Stein, A. (2004). The effect of postnatal depression on mother-infant interaction, infant response to the Still-face perturbation, and performance on an instrumental learning task. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579404044384

The World Bank (2020) World Bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 4 Aug 2020

Thombs, B. D., Kwakkenbos, L., Levis, A. W., & Benedetti, A. (2018). Addressing overestimation of the prevalence of depression based on self-report screening questionnaires. CMAJ, 190, E44–E49. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.170691

Thomson, H., Thomas, S., Sellström, E., & Petticrew, M. (2013). Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 9, 1–348. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2013.2

Tischler, V., Rademeyer, A., & Vostanis, P. (2007). Mothers experiencing homelessness: Mental health, support and social care needs. Health & Social Care in the Community, 15(3), 246–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00678.x

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., et al. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Tunstall, H., Pickett, K., & Johnsen, S. (2010). Residential mobility in the UK during pregnancy and infancy: Are pregnant women, new mothers and infants “unhealthy migrants”? Social Science and Medicine, 71, 786–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.013

United Nations Centre for Human Settlements (2000) Strategies to combat homelessness. United Nations Centre for Human Settlements, Nairobi

White, H., Wood, J., Fitzpatrick, S. (2018). Evidence and gap maps on homelessness. A launch pad for strategic evidence production and use Part 2: Global evidence and gap map of implementation issues. https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/59f07e67422cdf0001904c14/5bbe24f54fa950ad7c487003_CFHI_REPORT_PART2_V05.pdf

Wisner, K. L., Moses-Kolko, E. L., & Sit, D. K. Y. (2010). Postpartum depression: A disorder in search of a definition. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0119-9

Yelland, J., Sutherland, G., & Brown, S. J. (2010). Postpartum anxiety, depression and social health: findings from a population-based survey of Australian women. BMC Public Health, 10, 771. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-771

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the review aims, design and search strategy. LEK carried out the study selection process and drafted the paper, J M-K and SLP advised on the study selection process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Search strategy in medline

-

1.

exp Homeless Persons/

-

2.

homeless*.mp.

-

3.

(inadequat* adj2 (hous* or accommod*)).mp

-

4.

(insecur* adj2 (hous* or accommod*)).mp.

-

5.

(temporary adj2 (hous* or accommod*)).mp.

-

6.

(unstabl* adj2 (hous* or accommod*)).mp.

-

7.

(emergency adj2 (hous* or accommod*)).mp.

-

8.

(evict* adj2 threat*).mp.

-

9.

(rough adj1 sleep*).mp.

-

10.

houseless*.mp.

-

11.

roofless*.mp.

-

12.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11

-

13.

exp Postnatal Care/

-

14.

postnatal.mp.

-

15.

post-natal.mp.

-

16.

perinatal.mp.

-

17.

peri-natal.mp.

-

18.

postpartum.mp.

-

19.

post-partum.mp.

-

20.

matern*.mp.

-

21.

puerper*.mp.

-

22.

13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21

-

23.

depress*.mp.

-

24.

exp Depression/

-

25.

mood-disorder.mp.

-

26.

23 or 24 or 25

-

27.

12 and 22 and 26

Appendix 2 Key charities for grey literature in the UK

St Mungos

Joseph Rowntree foundation

SHELTER

CRISIS

The big issue foundation

Centre point

Homeless link

Mental health foundation.

Maternity action

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelly, L., Martin-Kerry, J. & Prady, S. Postnatal Depression and Homelessness in Women Living in High-Income Countries: A Scoping Review. Psychol Stud 68, 489–501 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-023-00736-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-023-00736-4