Abstract

Purpose

Qualitative research (QR) take advantage of a wide range of methods and theoretical frameworks to explore people’s beliefs, perspectives, experiences, and behaviours and has been applied to many areas of healthcare. The aim of this review was to explore how QR has contributed to the field of perioperative anesthesiology.

Source

We performed a systematic scoping review of published QR studies pertaining to the field of perioperative anesthesiology in three databases (CINAHL, Pubmed, and Embase), published between January 2000 and June 2018. We extracted data regarding publication and researchers’ characteristics, main study objectives, and methodological details. Descriptive statistics were generated for each data extraction category.

Principal findings

A total of 107 articles fulfilled our inclusion criteria. We identified 13 main research topics addressed by the included studies. Topics such as “patient safety,” “barriers to evidence-base medicine,” “patient experiences under local/regional anesthesia,” “training in practice,” “experiences of care,” and “implementation of changes in clinical practice” were commonly tackled. Others, such as “interprofessional communication”, “work environment,” and “patients’/healthcare professionals’ interactions” were less common. Qualitative research was often poorly reported and methodological details were frequently missing.

Conclusion

Qualitative research has been used to explore an array of issues in perioperative anesthesiology. Some areas may benefit from further primary research, such as interprofessional communication or patient-centred care, while other areas may deserve a detailed systematic knowledge synthesis. We identified suboptimal reporting of qualitative methods and their link to study findings. Increased attention to quality criteria and reporting standards in QR is called for.

Résumé

Objectif

La recherche qualitative (RQ) tire parti d’un large éventail de méthodes et de cadres théoriques afin d’explorer les croyances, perspectives, expériences et comportements des individus. Elle a été appliquée à de nombreux domaines des soins de santé. L’objectif de cette revue était d’explorer comment la RQ a contribué au domaine de l’anesthésiologie périopératoire.

Sources

Nous avons effectué une revue systématique de portée des études de RQ publiées entre janvier 2000 et juin 2018 dans le domaine de l’anesthésiologie périopératoire dans trois bases de données (CINAHL, Pubmed et Embase). Nous avons extrait les données concernant les caractéristiques de publication et des chercheurs, les principaux objectifs de l’étude et les détails méthodologiques. Des statistiques descriptives ont été générées pour chaque catégorie d’extraction de données.

Résultats principaux

Au total, 107 articles ont répondu à nos critères d’inclusion. Nous avons identifié 13 principaux sujets de recherche abordés par les études incluses. Des sujets tels que la « sécurité des patients », les « obstacles à la médecine fondée sur des données probantes », « les expériences des patients sous anesthésie locale/régionale », la « formation en pratique », les « expériences de soins » et la « mise en œuvre de changements dans la pratique clinique » étaient couramment abordés. D’autres thèmes, tels que la « communication interprofessionnelle », « l'environnement de travail » et les « interactions patients/professionnels de la santé » étaient moins courants. La recherche qualitative était souvent mal rapportée et les détails méthodologiques faisaient souvent défaut.

Conclusion

La recherche qualitative a été utilisée pour explorer un éventail de questions en anesthésiologie périopératoire. Certains domaines pourraient bénéficier d’autres recherches primaires, telles que la communication interprofessionnelle ou les soins centrés sur le patient, tandis que d’autres domaines mériteraient une synthèse systématique détaillée des connaissances. Nous avons identifié une communication sous-optimale des méthodes qualitatives et de leur lien avec les résultats de l’étude. Il est nécessaire de porter une attention accrue aux critères de qualité et aux normes de communication en RQ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Qualitative research (QR) aims to understand social phenomena in their natural settings, as well as the meanings that people bring to them.1 Qualitative research draws on a wide range of methods and theoretical frameworks to collect, analyze, and interpret non-numerical data, and is used to explore people’s beliefs, behaviours, perspectives, and experiences.2,3

The use of QR methods has become increasingly common in healthcare research. Qualitative methods have been used, for example, to explore patient and caregiver experiences of disease, disability, and medical interventions;4 patient-provider and interprofessional interactions;5 professional conflicts;6 human-machine interactions;7 professional development;8 and organizational culture.9 Qualitative research may be conducted alone or in conjunction with quantitative and experimental research and can contribute to evidence-based healthcare through hypothesis generation, development and validation of research instruments, and intervention development and evaluation.10 In the context of randomized controlled trials, QR has contributed to 1) understanding patient experiences of target conditions; 2) development of appropriate intervention content and delivery methods; 3) trial design and conduct; 4) development of process and outcome measures; and 5) understanding of trial outcomes.11 Recently, systematic reviews of qualitative studies have been conducted to summarize results and gain better understanding of particular phenomena.12,13,14,15

Several authors have called for more QR to enhance the practice of anesthesiology.16,17,18,19 As Shelton et al. have argued, “understanding how and why people act the way they do is essential for the advancement of anesthesia practice and rigorous, well-designed qualitative research can generate useful data and important insights”.20 As a first step towards advancing the use of QR in anesthesiology, we conducted a systematic scoping review of journal articles reporting on QR in the field. Systematic scoping reviews assess the amount and range of research literature available on a given topic and characterize the literature in terms of study design and other key attributes.21 We focused on perioperative anesthesiology as the field of research, which included the entire period from the pre-induction phase to postanesthesia care unit stay. Our specific aims were to describe how QR has been used in perioperative anesthesiology, with a focus on research topics addressed, researchers’ professional characteristics, and methodological approaches employed.

Methods

We report our methodology and results in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses scoping review extension (PRISMA-ScR) reporting guidelines.22

Eligibility criteria

Our inclusion criteria were full-length journal articles written in English or French, reporting on original research using QR methods for data collection (individual or group interviews, observations) and analysis (e.g., thematic analysis, grounded theory, phenomenology), either as stand-alone research or as part of a mixed-methods study, and with a primary focus of perioperative anesthesiology. For our study purposes, we defined perioperative anesthesiology as perioperative patient care and practice (i.e., pre-, intra-, and postoperative care) in which anesthesiologists are involved.23

We excluded records that were not journal articles (e.g., conference abstracts, theses, book chapters), not a report of original research (e.g., protocols, editorials), not focused on perioperative anesthesiology (e.g., simulation studies, education studies conducted outside of the clinical setting, studies on chronic pain or intensive care), and not reported in English or French. We also excluded studies that used only structured surveys or questionnaires. While such methods may sometimes produce non-numerical data, survey research design and analysis reflect a more positivist understanding of the nature of the world, in contrast with the constructivist paradigms of QR. Only records published between January 2000 and June 2018 were eligible. We chose the year 2000 as our cut-off because relatively few clinical journals published QR prior to 2000.24

Literature search strategy

We designed our search strategy with the help of a librarian at our medical faculty. The two main prespecified concepts for our search were “anesthesiology” as a discipline and “qualitative research” as a type of study design. We conducted a rapid search of the literature to identify relevant publications that were then analyzed for text words used in the title and abstract, and index terms used. These informed the development of our search strategy. We also screened the thesaurus of PubMed and Medline (MeSH), Embase (EmTree), and CINAHL to find additional keywords. We then searched PubMed, Embase, and CINAHL databases for articles published between January 2000 and June 2018. The final search strategy for the three databases, including equations, can be found in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM), eAppendix 1. As a form of quality control, we checked that all QR publications that we were previously aware of had been identified by our search.

Selection of sources of evidence

We used both DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, ON, Canada) and Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to manage our data and organize the review process. We first downloaded all records to DistillerSR. One investigator (M.G.) performed the initial screening of all publications titles and abstracts using the prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the event of any doubt, articles were kept at this stage. The selected publications were then extracted to Excel tables to facilitate the review process. Two other investigators (P.H. and G.L.S.) then independently reviewed the publications list to confirm inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consensus between the three authors.

Data items

We extracted the following elements from the selected studies: publication characteristics; study aims and objectives; research team characteristics; type of study (QR or mixed); theoretical framework; data collection methods; data analysis methods; research quality criteria (see ESM, eAppendix 2 for details on the subcategories). Except for two categories, “main topic of research” and “general objective” (see below), all of the subcategories were prespecified.

Data charting and synthesis process

M.G., P.H., and G.L.S. first independently read and extracted data from ten articles. Results were compared and discussed, and any charting differences were resolved through discussion among the three authors and resulted in slight modifications in the initial coding scheme to enhance coding accuracy. M.G. read and extracted data from all the remaining articles. M.G. and P.H. then extracted data from 12 articles each (for a total of 24), to check for agreement. For the categories of “main topic of research” and “general objective”, M.G. first extracted the aims and objectives as stated in the articles. All three authors then read, discussed, and grouped the studies into inductively generated categories.25 Once data extraction was completed, descriptive statistics were generated for each of the data categories.

Results

Included studies

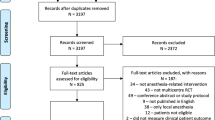

Our initial search strategy produced a total of 2,131 records, with 241 from CINAHL, 520 from PubMed, and 1,370 from Embase. After removing duplicates, 2,024 records remained. The first title/abstract screening resulted in 370 relevant records. After further abstract screening, 132 articles remained. After full-text assessment by all the authors, 107 articles were identified that fulfilled all inclusion criteria (See PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1). The full list of articles is given in the ESM, eAppendix 3. M.G. extracted data from the 107 articles and the inter-rater agreement for the charting of 24 randomly selected articles was 96%.

Publication characteristics

All 107 articles were published in peer-reviewed journals. Forty-three percent (n = 46) were published in medical journals, 37% (n = 40) in nursing journals, and 20% (n = 21) in other journals (social sciences, public health, innovation and technology). Almost half (n = 53) of the publications were in anesthesiology-specific journals (either nursing or medical). The number of published qualitative studies on topics relating to perioperative anesthesiology generally increased from 2000 to 2018 (Fig. 2).

Main topic of research and general objective

Included studies investigated 13 main topics of research: patient safety (10%; n = 11), barriers to best care (8%; n = 9), professional roles (8%; n = 9), non-technical skills (7%; n = 8), training and knowledge in practice (13%; n = 14), interprofessional communication (4%; n = 4), transfer of information (4%; n = 4), experiences of care (10%; n = 11), patients’ experiences under local/regional anesthesia (12%; n = 13), patients’ (or family members’) experiences of general anesthesia (5%; n = 5), implementation of changes in clinical practice (14%; n = 15), patients/healthcare professionals interaction (3%; n = 3), and work environment (2%; n = 2). Within each main topic, specific research objectives varied; Table 1 summarizes the study topics and research objectives and ESM eAppendix 3 provides further details for each publication included in the analysis.

Research team characteristics

Sixty-eight percent (n = 73) of studies were conducted by multi-professional teams and 27% (n = 29) by single-professional teams (either nurses only, doctors only, or other professionals only); 79% (n = 85) of teams included one or more nurse anesthetists or anesthesiologists. Five percent of studies (n = 5) were conducted by a single author. Fifty-five percent (n = 59) of the articles included at least one author with education in non-medical or non-nursing sciences (social sciences, education, psychology, or technology).

Fifty-one percent (n = 55) of teams were located in English-speaking countries (UK, USA, Canada, Australia) whereas 34% (n = 36) were based in Scandinavian countries (mainly Denmark and Sweden). All but one of the articles were written in English. The sole publication in French was authored by a team located in France.

While a majority of articles published in medical journals had at least one author with a background in social sciences, education, or public health (34/46), only few articles published in nursing journals did (9/40).

Type of study and theoretical framework

Most of the articles in our review reported on qualitative, single-method studies (85%; n = 91). Only 16 articles (15%; n = 16) reported on mixed-methods studies. We extracted the keywords used by authors to refer to their theoretical and methodological approach (Table 2). In nearly half of the publications (47%; n = 50), no particular methodological approach was mentioned. Keywords used in the remaining articles included ethnography (14%; n = 15), phenomenology (11%; n = 12), grounded theory (9%; n = 10), qualitative description (5%; n = 5), and phenomenography (5%; n = 5). Other methodologies mentioned less frequently (9%; n = 10) included critical incident technique, theoretical domains framework, activity theory, cognitive systems engineering, social constructivism paradigm theory, narrative theory, work system analysis, and proactive risk assessment.

Data collection methods

Table 3 presents the main data collection methods used. Individual interviews, either semi-structured or in-depth interviews, were by far the most common method used (85%; n = 91). Few studies (15%; n = 16) used mixed (qualitative and quantitative) methods.

Data analysis methods

We extracted the key words used to describe data analysis methods. The most frequently mentioned method was thematic analysis (52%; n = 56); other methods mentioned included content analysis (15%; n = 16), grounded theory (6.5%; n = 7), phenomenographic analysis (4%; n = 4), discourse analysis (2%; n = 2), framework analysis (2%; n = 2), and others (15%; n = 16). In four publications (4%), no information was provided about analysis methods.

Research quality criteria

Several quality criteria have been proposed for evaluating QR.26,27 Of particular concern is transparency regarding all aspects of the research process. Although a full evaluation of research quality was beyond the scope of this review, we looked at three frequently mentioned quality criteria that were relatively easy to identify as present or absent in the publications: author reflexivity, use of verbatim quotes to support analysis claims, and ethical review.

Reflexivity

Reflexivity has been defined as “the process of a continual internal dialogue and critical self-evaluation of researcher’s positionality as well as active acknowledgement and explicit recognition that this position may affect the research process and outcome and is considered an important criterion of quality in qualitative research”.28 Potential researcher bias and study limitations were mentioned in 72 articles (67%).

Presentation of evidence to support analysis claims

Generally, researchers should provide information that allows the reader to understand and critically assess the interpretive process; one crucial element of that is the presentation of empirical data, usually in the form of verbatim quotes from respondents. Our review found that a large majority of articles (91%; n = 97) presented some original data and verbatim quotes of study participants to illustrate the coding and interpretation process, and to support study conclusions. Nevertheless, we did not assess the adequacy of the data presented with regards to the study conclusions.

Ethical review

Transparency regarding how data were produced is important for assessing research results. Whether and how ethical review and informed consent were obtained will have consequences for research outcomes. In our review, we determined whether or not studies reported research ethics board approval. Such approval was mentioned in 92 (86%) articles.

Discussion

We conducted a systematic scoping review of published journal articles reporting on QR pertaining to the field of perioperative anesthesiology. Our review identified a steady increase in QR publications over the years, while the number of anesthesiology-related publications was generally stable over the last two decades.29

Most of the articles we reviewed reported on stand-alone qualitative studies involving individual interviews conducted in English-speaking and Scandinavian countries on topics related to health professional experiences, opinions, and practices. Studies reflected a variety of theoretical and methodological frameworks, although nearly half made no mention of their approach. Descriptive analysis (as opposed to theory-building) was most common, reflected in terms such as thematic or content analysis. While most articles provided information about ethical review and consent procedures and presented evidence (verbatim quotes) to support study conclusions, a third of articles did not discuss potential sources of interpretive bias and study limitations.

Study topics addressed in perioperative anesthesiology reflected interest in improving safety and quality of care quality as well as patient experiences. For example, QR has been used to understand the risks to patient safety and the origin of adverse events in practice. The impact of personal, environmental and team factors on barriers to the proficient use of evidence-based medicine and guidelines have also been exposed using QR.30

Many studies included in our review explored health professionals’ experiences, views, and practices. A number of studies explored how anesthesiologists view their professional role;31,32 others described the non-technical skills employed by anesthesiologists33,34 and examined how leadership style affects healthcare delivery.35 Yet again, other studies explored the experiences of healthcare professionals when caring for specific patients or in specific settings.36 Studies that focused on patient (or family) experiences of anesthesia were less frequent and mainly looked at the experience of patients under local/regional anesthesia.37

A number of topics appear to be understudied and would benefit from further QR. These include interprofessional communication, the work environment, and transfer of information among professionals working together in the operating room. The operating room is an interprofessional space and the impact of differing medical and personal cultures has yet to be studied.

Another topic that we believe would merit further research is patient centredness in anesthesiology. A scoping review of patient-centred care in healthcare generally highlighted the core values of patients (health promotion, communication, and partnership) and called for more empirical approaches to evaluate new patient-centred care and outcomes;38 it would be interesting to explore these issues in perioperative medicine, especially with respect to aging populations and the need for new outcomes to evaluate the futility of some surgical measures.

Overall, QR publications in perioperative anesthesiology are increasing. Similar to our findings, a systematic review of QR in surgery found that QR gained popularity over the years and that interviews were the most used data collection method.15 Nevertheless, while the authors reported that only 8% of the articles were published in surgery-specific journals, our review found that almost half of publications were in anesthesiology-specific journals. This difference may reflect greater attention by anesthesiologists to human factors affecting their practice.39

In contrast to our results, a review of QR in otolaryngology found that most QR studies focused on patient experiences of healthcare, with few studies exploring health professional experiences and opinions.40 The focus on professional practices and experiences in anesthesiology may reflect the importance of teamwork and the high-risk nature of anesthesiology practice. Qualitative research can clearly contribute to understanding risks to patient safety, and explore how technology and standardized practices are implemented.41

The present scoping review identified deficiencies in the reporting of QR study methods. A previous review of QR in health services research found similar deficiencies;42 although the level of detail provided about research methods has improved over the years, in the words of the authors, there persists “a troubling lack of adequate methods description in 40% to 60% of qualitative research articles”.42

So what can be done to improve the quality and contributions of QR to health research? Devers43 reflects on the accomplishments to date as well as future challenges regarding the contributions of QR to health services research. Her conclusions are equally relevant for QR in anesthesiology. She argues that while a certain degree of progress has been made, “qualitative research still has a long way to go”, and that researchers should be better trained in qualitative and mixed-methods research to successfully apply them to the challenges of healthcare improvement.43

Many resources exist to help researchers strengthen the reporting of QR. For example, Tong et al. developed a checklist of 32 items to be included in QR reports. The aim of such guidelines is to provide readers with enough information to be able to assess the methodological rigour and credibility of their findings.44 Some editorials now recommend authors to refer to such guidelines,45 and researchers in anesthesiology should avail themselves of the many opportunities and resources available to help ensure quality in QR.46,47,48,49,50

There are a number of limitations to our review. It was limited to describing the uses of QR in the field of perioperative anesthesiology. We did not conduct a thorough assessment of study quality. Such assessment will be essential when conducting future systematic knowledge synthesis. A further limitation is the fact that the initial screening of studies was conducted by only one author. Nevertheless, frequent discussion and cross checking by all three authors were employed to ensure all relevant studies were included.

In conclusion, the present systematized review of QR in anesthesiology has identified broad topics that deserve either further primary research or systematic knowledge synthesis. The findings also highlight the need to improve QR reporting. Future efforts should focus on diversifying the focus of QR, conducting targeted knowledge syntheses, and improving methodological and reporting quality.

References

Fossey E, Harvey C, McDermott F, Davidson L. Understanding and evaluating qualitative research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002; 36: 717-32.

Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks C, US: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1994.

Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995; 311: 42-5.

Hallstam A, Stalnacke BM, Svensen C, Lofgren M. Living with painful endometriosis - a struggle for coherence. A qualitative study. Sex Reprod Healthc 2018; 17: 97-102.

Gotlib Conn L, Reeves S, Dainty K, Kenaszchuk C, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional communication with hospitalist and consultant physicians in general internal medicine: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-437.

Bajwa NM, Bochatay N, Muller-Juge V, et al. Intra versus interprofessional conflicts: implications for conflict management training. J Interprof Care 2020; 34: 259-68.

Pals RA, Hansen UM, Johansen CB, et al. Making sense of a new technology in clinical practice: a qualitative study of patient and physician perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res 2015; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1071-1.

Jensen RD, Seyer-Hansen M, Cristancho SM, Christensen MK. Being a surgeon or doing surgery? A qualitative study of learning in the operating room. Med Educ 2018; 52: 861-76.

Marshall M, Sheaff R, Rogers A, et al. A qualitative study of the cultural changes in primary care organisations needed to implement clinical governance. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52: 641-5.

Popay J, Rogers A, Williams G. Rationale and standards for the systematic review of qualitative literature in health services research. Qual Health Res 1998; 8: 341-51.

O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ, Drabble SJ, Rudolph A, Hewison J. What can qualitative research do for randomised controlled trials? A systematic mapping review. BMJ Open 2013; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002889.

Bergs J, Lambrechts F, Simons P, et al. Barriers and facilitators related to the implementation of surgical safety checklists: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. BMJ Qual Saf 2015; 24: 776-86.

Edmondson AJ, Birtwistle JC, Catto JW, Twiddy M. The patients' experience of a bladder cancer diagnosis: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. J Cancer Surviv 2017; 11: 453-61.

Teixeira Rodrigues A, Roque F, Falcão A, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Understanding physician antibiotic prescribing behaviour: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2013; 41: 203-12.

Maragh-Bass AC, Appelson JR, Changoor NR, Davis WA, Haider AH, Morris MA. Prioritizing qualitative research in surgery: a synthesis and analysis of publication trends. Surgery 2016; 160: 1447-55.

Larsson J, Holmstrom I, Rosenqvist U. Professional artist, good Samaritan, servant and co-ordinator: four ways of understanding the anaesthetist's work. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003; 47: 787-93.

Wijeysundera DN, Feldman BM. Quality, not just quantity: the role of qualitative methods in anesthesia research. Can J Anesth 2008; 55: 670-3.

Bajwa SJ, Kalra S. Qualitative research in anesthesiology: an essential practice and need of the hour. Saudi J Anaesth 2013; 7: 477-8.

Nileshwar A, Khymdeit E. Research in anesthesiology: time to look beyond quantitative studies. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol 2016; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-9185.188832.

Shelton CL, Smith AF, Mort M. Opening up the black box: an introduction to qualitative research methods in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 2014; 69: 270-80.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J 2009; 26: 91-108.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169: 467-73.

Grocott MP, Pearse RM. Perioperative medicine: the future of anaesthesia? Br J Anaesth 2012; 108: 723-6.

Yamazaki H, Slingsby BT, Takahashi M, Hayashi Y, Sugimori H, Nakayama T. Characteristics of qualitative studies in influential journals of general medicine: a critical review. Biosci Trends 2009; 3: 202-9.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006; 3: 77-101.

Majid U, Vanstone M. Appraising qualitative research for evidence syntheses: a compendium of quality appraisal tools. Qual Health Res 2018; 28: 2115-31.

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014; 89: 1245-51.

Berger R. Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res 2013; 15: 219-34.

Chen SY, Wei LF, Ho CM. Trend of academic publication activity in anesthesiology: a 2-decade bibliographic perspective. Asian J Anesthesiol 2017; 55: 3-8.

Swennen MH, van der Heijden GJ, Blijham GH, Kalkman CJ. Career stage and work setting create different barriers for evidence-based medicine. J Eval Clin Pract 2011; 17: 775-85.

Wong A. From the front lines: a qualitative study of anesthesiologists' work and professional values. Can J Anesth 2011; 58: 108-17.

Schreiber RS, MacDonald MA. Keeping vigil over the profession: a grounded theory of the context of nurse anaesthesia practice. BMC Nurs 2010; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6955-9-13.

Lyk-Jensen HT, Jepsen RM, Spanager L, Dieckmann P, Østergaard D. Assessing nurse anaesthetists' non-technical skills in the operating room. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014; 58: 794-801.

Livingston P, Zolpys L, Mukwesi C, Twagirumugabe T, Whynot S, MacLeod A. Non-technical skills of anaesthesia providers in Rwanda: an ethnography. Pan Afr Med J 2014; DOI: https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2014.19.97.5205.

Paquin H, Bank I, Young M, Nguyen LH, Fisher R, Nugus P. Leadership in crisis situations: merging the interdisciplinary silos. Leadersh Health Serv (Bradf Engl) 2018; 31: 110-28.

Boquelet R, Leclerc C. Optimiser la prise en charge du patient handicapé mental avant l’anesthésie. Prat Anesth Reanim 2018; 5970: 168-71.

Webster F, Bremner S, McCartney CJ. Patient experiences as knowledge for the evidence base: a qualitative approach to understanding patient experiences regarding the use of regional anesthesia for hip and knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011; 36: 461-5.

Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2014; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-271.

Jones CP, Fawker-Corbett J, Groom P, Morton B, Lister C, Mercer SJ. Human factors in preventing complications in anaesthesia: a systematic review. Anaesthesia 2018; 73 Suppl 1: 12-24.

Mather MW, Hamilton D, Robalino S, Rousseau N. Going where other methods cannot: a systematic mapping review of 25 years of qualitative research in otolaryngology. Clin Otolaryngol 2018; 43: 1443-53.

Yee KC, Wong MC, Turner P. Qualitative research for patient safety using ICTs: methodological considerations in the technological age. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017; 241: 36-42.

Weiner BJ, Amick HR, Lund JL, Lee SY, Hoff TJ. Use of qualitative methods in published health services and management research: a 10-year review. Med Care Res Rev 2011; 68: 3-33.

Devers KJ. Qualitative methods in health services and management research: pockets of excellence and progress, but still a long way to go. Med Care Res Rev 2011; 6: 41-8.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19: 349-57.

Biomed Central. Editorial policies. Biomed central: Springer Nature; 2020 [Standards of reporting for authors]. Available from URL: https://www.biomedcentral.com/getpublished/editorial-policies#standards+of+reporting (accessed August 2021).

Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res 1999; 34(5 Pt 2): 1101-18.

Moser A, Korstjens I. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: introduction. Eur J Gen Pract 2017; 23: 271-3.

Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2020.

Noyes J, Booth A, Cargo M, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance series-paper 1: introduction. J Clin Epidemiol 2018; 97: P35-8.

Albury C. Oxford Qualitative Courses: Short Courses in Qualitative Research Methods; 2020 [Nuffield departement of primary care health sciences, Medical science division.]. Available from URL: https://www.phc.ox.ac.uk/study/short-courses-in-qualitative-research-methods (accessed August 2021).

Author’s contributions

Mia Gisselbaek, Patricia Hudelson, and Georges L. Savoldelli were involved in the conception and design of the study, data collection, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Mafalda Vieira Burri, Research Associate, University of Geneva Medical Faculty Library, for her invaluable assistance in designing our search strategy.

Disclosures

None.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Division of Anesthesiology, Department of Anesthesiology, Clinical Pharmacology, Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine, Geneva University Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. No external funding was received for this study.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Stephan K.W. Schwarz, Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Université de Genève.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Part of this work has been previously published as: - Abstract and poster for Euroanaesthesia congress (online), 28–30 November 2020. - Abstract published in: Supplementum 246: Swiss Anaesthesia 2020 - Annual Congress of the Swiss Society of Anaesthesiology and Resuscitation (SGAR-SSAR) https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20395; Publication Date: 28.10.2020; Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20395

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gisselbaek, M., Hudelson, P. & Savoldelli, G.L. A systematic scoping review of published qualitative research pertaining to the field of perioperative anesthesiology. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 68, 1811–1821 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02106-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-021-02106-y