Abstract

Purpose

Research describing opioid misuse in children after surgery currently describes single specialties, short follow-up, and heterogeneous data not conducive to comparative discussion. Our primary objective was to quantify opioids prescribed to pediatric surgical patients on discharge from hospital. Secondary objectives were quantifying opioids remaining unused at four-week follow-up, and family attitudes to safe storage and disposal.

Methods

We conducted a prospective observational study under counterfactual consent with telephone follow-up at four weeks of children who had undergone a surgical procedure and filled an opioid prescription at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada. Exclusion criteria included opioid use within the previous six months, history of chronic pain, or discharge to a rehabilitation facility. Pre- and post-discharge prescribing, dispensing, and consumption data were collected prospectively in addition to parental reports of home opioid use. Opioid-dosing was converted to oral morphine milligram equivalents (MME).

Results

There were 8,672 MMEs prescribed to 110 patients. Twenty-one patients were lost to follow-up, accounting for 1,416 MME. Of the remaining 7,256 MME, 67% went unused. At follow-up, 78% of unused opioid remained in the home. Most opioids were stored in an easily accessible location in the home.

Conclusion

These findings confirm overprescribing of opioids to pediatric surgical patients. Families tend not to return opioids that exceed post-discharge analgesic requirements at home and many of the reported disposal methods are unsafe. We recommend future studies focus on optimizing opioid prescriptions to meet, but not excessively surpass, home pain management requirements, and to encourage safe opioid disposal/return methods.

Trial registration

www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03562013); registered 7 June, 2018.

Résumé

Objectif

La recherche s’intéressant à la mauvaise utilisation des opioïdes après une chirurgie chez des enfants décrit actuellement des spécialités uniques, un suivi de courte durée et des données hétérogènes ne permettant pas de déboucher sur un débat comparatif. Notre objectif principal était de quantifier les opioïdes prescrits à des patients chirurgicaux pédiatriques au moment de leur congé de l’hôpital. Les objectifs secondaires étaient de quantifier les opioïdes inutilisés restant après quatre semaines de suivi et l’attitude des familles envers un stockage et une élimination sécuritaires.

Méthodes

Nous avons réalisé une étude observationnelle prospective sous consentement contre-factuel avec suivi téléphonique à quatre semaines d’enfants qui avaient subi une procédure chirurgicale et avaient reçu une prescription honorée d’opioïdes au Hospital for Sick Children de Toronto (ON, Canada). Les critères d’exclusion étaient l’utilisation d’opioïdes dans les six mois précédents, des antécédents de douleur chronique et un congé vers un établissement de réadaptation. Les prescriptions avant et après le congé, les données de remise et de consommation des médicaments ont été collectées de manière prospective en plus des rapports parentaux sur l’utilisation des opioïdes au domicile. Les doses d’opioïdes ont été converties en milligrammes équivalents de morphine (MEM) orale.

Résultats

Il y a eu 8 672 MEM prescrits à 110 patients. Vingt et un patients représentant 1 416 MEM ont été perdus au suivi. Sur les 7 256 MEM restants, 67 % n’ont pas été utilisés. Au suivi, 78 % des opioïdes non utilisés étaient encore au domicile. La majorité d’entre eux étaient conservés dans un endroit facile d’accès au domicile.

Conclusion

Ces constatations confirment la prescription excessive d’opioïdes aux patients chirurgicaux pédiatriques. Les familles ont tendance à ne pas rapporter les opioïdes qui dépassent les besoins analgésiques après le congé et un grand nombre des méthodes d’élimination indiquées ne sont pas sécuritaires. Nous recommandons de concentrer les études futures sur l’optimisation des prescriptions d’opioïdes afin de satisfaire, mais sans dépasser de façon excessive, les besoins pour la gestion de la douleur au domicile et d’encourager des méthodes de retour/élimination sécuritaire des opioïdes.

Enregistrement de l’essai clinique

www.ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03562013); Enregistré le 7 juin 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In 2016, the Centers for Disease Prevention & Control reported 42,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States making it the first year on record that road traffic accidents were surpassed as the leading cause of accidental death.1 Also in 2016, 2,861 apparent opioid-related deaths were reported in Canada; this exceeded the average number of Canadians killed daily in motor vehicle collisions in 2015.2 A population-based study of 1,359 opioid-related deaths in Ontario reported seven percent had used opioids prescribed for family or friends.3 Neither report provided data on opioid use/misuse in children.

In 2012, a cohort study showed that 7.1% of opioid-naïve adults undergoing short-stay surgeries in Ontario filled opioid prescriptions within seven days of surgery, and 7.7% of all patients studied were still prescribed opioids one year later.4 Two systematic reviews examining opioid use in postoperative adults reported 67–92% of opioids dispensed at discharge go unused and remain in the home after medical use ceases.5,6

There is insufficient evidence to conclude whether opioid use for pain management in children after surgery is associated with future opioid misuse disorders. Nevertheless, an estimated 13% of American high-school seniors reported subsequent nonmedical use of prescription opioids.7 Some 5% of adolescents also refill outpatient opioid prescriptions greater than 90 days after surgery, suggesting prescribed postoperative opioids may present an opportunity for misuse and diversion.8 In 2017, Health Canada reported that 33% of opioid use in the previous year was not associated with a prescription and the most common source of non-prescription opioids was a family member.9 Research concerning the prescribing and postoperative home use of opioids in pediatric patients has been limited to single subspecialty populations with short follow-up timeframes.10,11,12,13 A Canadian study that prospectively reported morphine prescribing and home use in children after surgery identified a need to re-evaluate the quantity of morphine prescribed and dispensed after pediatric surgery. However, the follow-up period was only three days and many patients were still receiving ongoing pain management.14

We designed this study to prospectively examine the current status of opioid prescribing at postoperative discharge in a Canadian academic pediatric hospital. The primary objective was to quantify the morphine milligram equivalent (MME) of opioids prescribed to pediatric surgical patients at hospital discharge. Our secondary objectives were to compare the MME of opioid prescribed to that consumed in the home, and to quantify the MME of unused opioids remaining in the home one month after cessation of use. Other objectives were to describe family attitudes to opioid storage, safe opioid return, and/or disposal.

Methods

Study design and population

This was a prospective observational study with telephone follow-up at four weeks. Because informed consent would likely introduce bias to parental behaviour we sought to secure counterfactual consent from participants as consistent with deception methodologies in psychology and social sciences. Counterfactual consent is delivered when two conditions are satisfied: 1) the participant is not ignorant of any fact that would cause them to withhold their consent if they were aware of it, and 2) they voluntarily consent.15 Deception about study goals does not violate autonomy but deception about the existence of the study does. We proposed that participants would give consent for a study examining the quality and safety of their home pain management. We did not mislead potential participants as to any item that might cause harm, and participants were aware they were consenting to a research study. Study design was guided by and received approval from local institutional Research Ethics Board (REB). This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03562013).

Study population comprised male and female children (0–18 yr) who had undergone a surgical procedure in the seven days prior to an opioid prescription being filled at this institution’s commercial pharmacy. Surgical procedure was defined as any surgical intervention provided by a surgeon in the operating rooms, excluding procedures such as endoscopy, interventional radiology, lumbar punctures, and non-interventional examinations under anesthesia. The parent filling the prescription was approached for consent as they were identified as the person responsible for administering and storing opioid medications in the home. Because of telephone follow-up, participants were required to have a strong command of the English language (i.e., no interpreter needed). Children who had used opioid medication at home within the previous six months, had reported a history of chronic pain, or were discharged to a rehabilitation facility were excluded. A convenience sample of 100 patients was chosen to provide a snapshot of opioid prescribing practices not limited to a particular procedure or surgical specialty. Approval was granted by REB to recruit ten additional families at a time to achieve four-week follow-up of greater than 80 participants.

Materials

Pre-/post-discharge opioid data were extracted from electronic health records (EHR) (Epic, Epic Systems, Verona, WI, USA). Collected data included opioids prescribed/dispensed, opioid concentration and dose, dose frequency, total dose prescribed, expected duration of therapy, and participant’s birthdate, weight, and opioid consumption in the 24 hr prior to discharge. Opioids were prescribed in liquid or tablet form, so doses represent the single amount administered at a time.

Home opioid use was recorded by phone interview with the consenting parent four weeks post-discharge using a scripted questionnaire developed in accordance with questionnaires used previously in similar studies (Appendix). Data included total MME and number of doses of opioid administered, day on which opioid administration ceased, location security and accessibility of opioid storage, level of comfort regarding presence of opioids in the home, and intended mode of disposal.

Procedure

This study took place at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada, from July 2018 to February 2019. Approximately 12,000 surgical procedures are performed each year (70–80% of which are ambulatory). Enrolment followed a consecutive sampling method until a convenience sample size > 80 was met. Prospective participants were screened by the hospital’s commercial pharmacy staff. Families who presented with opioid prescriptions on surgical discharge were directed to a pharmacist who explained the nature of the study while prescriptions were being prepared. No emphasis was placed on opioids during this discussion and no restrictions were placed on home use. If the family agreed to take part, one parent was identified as the subject for consent and consent was taken by the pharmacist.

Four weeks post enrolment, families were contacted by phone to complete the questionnaire. Families who could not be reached were called an additional ten times in the subsequent four-week period; uncontactable families were withdrawn from follow-up. Pre- and post-discharge opioid data were extracted from hospital EHR by two investigators simultaneously (C.M., M.C.K.). Data were checked and confirmed in duplicate at time of extraction and transferred to an Excel spreadsheet. Questionnaire data were input into the external instance of REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted by The Hospital for Sick Children, before being exported and merged with the Excel spreadsheet. Families subsequently received a debrief phone call from the primary investigator (C.M.) disclosing the counterfactual nature of this study. No further data were collected during this call but the opportunity was taken to reinforce safe disposal methods if unused opioids remained in the home.

Statistical analysis

For comparison purposes, opioids were converted to MME doses of morphine sulfate using standard ratios.16 Twenty-four hour pre-to-post discharge consumption ratios were calculated by dividing total MME consumed in 24-hr prior to discharge by total MME prescribed for first 24-hr following discharge.17 All data are presented as descriptive statistics.

Results

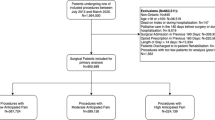

One hundred and ten families were recruited from July 2018 to February 2019. Twenty-one families were lost to follow-up, leaving 89 complete data sets (Fig. 1). Approximately 15 families were recruited per month, except for month five because of issues with new software implementation at the commercial pharmacy and month six which encompassed a Christmas “slowdown”. Table 1 provides demographic information and details pertaining to surgical specialties and specific operations. Nine children (10%) did not receive opioids in the 24-hr period before hospital discharge. Of the remaining 80 children (90%), the median [interquartile range (IQR)] pre-discharge opioid consumption was 0.69 [0.45–1.04] MME/kg. The median 24-hr MME prescribed at discharge was 1.11 [0.80–1.38] MME/kg.

Eight thousand six hundred and seventy-two MME were prescribed to 110 patients, of which 21 were lost to follow-up (1,416 MME). Table 2 shows 7,256 MME were prescribed and dispensed to 89 families with complete follow-up. This represents a median [IQR] dose per patient of 10 [10–20]. Eighty-one (91%) children were prescribed morphine and eight (9%) received hydromorphone. At follow-up, four families could not recall how much opioid they had used. Eighty-four (94%) families also provided children with acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in combination with opioids, with 52 (62%) providing additional medications regularly, and 32 (38%) providing additional medications as needed. Five (6%) families indicated they did not provide any additional pain medication.

Table 3 reports the MME of unused opioids remaining after cessation of intake. Amongst the 85 families that could recall how much opioid was used, a median [IQR] dose of 8 [5–12] accounting for 4,829 MME (67%) went unused. Twenty-five families used no opioids in the home post-discharge, accounting for a median [IQR] of 10 [6–12] unused doses (1,269 MME). Twenty-seven families used 1–24.9% of opioids prescribed, accounting for a median [IQR] of 11 [9–19] unused doses (2,664 MME). These 52 families accounted for 3,932 MME (81%) of all unused (4,829) MME. The median duration of opioid use post-discharge across all participants was 2 [0–4] days.

At follow-up, seven of 89 families had used all opioids prescribed and 10 families had returned unused opioids to the local pharmacy (816 MME). In the remaining families, 3,781 of 4,829 unused MME (78%, or 9 [6–15] doses) remained in the home. Six families discarded the remaining prescription (235 MME, or 7.5 [5.3–9.0] doses per family) prior to follow-up and 21 families were lost to follow-up (1,416 MME, or 10 [6.5–15.5] doses per family). Therefore, 1,651 MME (9 [5.3–14.0] doses per family) remained unaccounted for and/or improperly disposed of. Table 4 reports the MME of opioids remaining in the home at four-week follow-up.

Figure 2 reports the location of opioid storage as declared at follow-up. The kitchen cupboard was the most frequently reported location (70%). Thirty-eight families reported the location of opioid storage changed once opioid use ceased, while 50 families indicated no such change. Fifteen families (17%) reported the location of opioid storage was not accessible to others. Seventy-one families (80%) reported they were comfortable having opioids in the home, and 18 families (20%) indicated they were uncomfortable with opioids in the home.

Sixty-five percent of families (58/89) reported they intended to return the unused opioids to a local pharmacy. Ten families (11%) reported they had not disposed of opioids and were keeping medication for future use (“just in case”). Three families reported they had more than one opioid prescription filled and stored simultaneously in the home. Unsafe disposal methods documented included “pouring it into the recycle bin” and “burying it in the woods”. One family reported they had given another child (i.e., not the child whom opioid was prescribed to) a “small dose” of opioid for non-surgical pain (teething) one week after opioid use had ceased in the child who underwent surgery. Sixty-two families still had outstanding opioid doses in the home at time of telephone debrief.

Discussion

This study is the first of its type in Canadian pediatric surgical patients and we report that 67% (4,829 MME) of opioids prescribed at surgical discharge went unused at home. We also report that 78% (3,781 MME) of unused opioids remained in the home one month after discharge from hospital. Almost 60% of patients (52/89) did not consume more than 25% of opioids prescribed, and opioids continued to be stored in easily accessible locations throughout the home many weeks after use had ceased.

Recent investigations into pediatric home opioid consumption after hospital discharge report similar findings to adult surgical populations.7,18,19 In 2015, a study reported data from 223 children undergoing minor elective procedures, with four-day follow-up, in which 14% took zero doses of opioids dispensed on discharge. By day 3, 34% of patients had only received one to two doses, while 39% of families had discontinued the opioid treatment altogether in favour of over-the counter analgesics.20 Our own findings report almost 30% of patients (25 of 89) took none of the prescribed opioid doses upon discharge home. This discrepancy may be explained by differing surgical complexity and pain requirements in addition to the fact that pediatric patients in Ontario cannot receive prescriptions for “mixed-drug” combinations such as codeine/acetaminophen or hydrocodone/acetaminophen, as were commonly dispensed in other studies,10,20,21 particularly those conducted in the United States. Indeed, differing methodologies (surgical population studied, opioids and formulations studied, lack of conversion to MMEs, differing follow-up intervals) explain the observed differences in absolute incidence of opioid overprescribing. Nevertheless, our findings (which report 67% of prescribed opioids went unused and 80% of unused drug remained in the home) remain consistent with other studies reporting overprescribing and under-utilization of opioids in children after postoperative discharge.11,14,20,21 Our findings describing storage and disposal practices are also consistent with previous research, with 65% of participants reporting they stored opioids in the kitchen (compared with 70% in our study) and 55% of participants indicating they would safely dispose of the excess opioids (compared with 65% in our study).22

Opioid overprescribing within pediatric surgical populations, coupled with unsafe storage and disposal methods in the home, are significant concerns considering the current climate of opioid misuse, diversion, and substance use disorders in the community at large. With current emphasis on earlier discharges from hospital, enhanced recovery after surgery and developments/refinements of the perioperative surgical home, it is clear that additional studies focused on addressing and minimizing pediatric surgical overprescribing are required. As reported in this study, the total amount of opioids being prescribed and dispensed on discharge exceeds that which is ultimately needed, with many prescriptions providing weeks’ worth of medication although home consumption often ends within the first few days. Future studies must focus on implementing interventions that minimize overprescription and dispensing, while taking into account the importance of not leaving some vulnerable patients in a position of unmanageable pain due to the absence or under-prescribing of opioid analgesia. It would seem reasonable to suggest that opioid prescription and administration take the following points into account: a) consider pre-discharge opioid requirements and consumption, b) administer opioids in the home in addition to regular round-the-clock simple analgesics, and c) focus on discontinuing opioids by day 3 or 4 post discharge after most minor procedures. Local data reflecting department-wide procedural pain requirements should be evaluated and utilized to provide optimal safe home opioid prescribing while ensuring no child is discharged with inadequate pain management plans. With respect to safe storage and disposal practices, more emphasis must be implemented at levels of care, from ward-based education from nurses, pharmacists, and physicians, to discharge prescriptions from dispensing pharmacists, and to public health information and social media representation. After Health Canada implemented mandatory information sheets to accompany opioid prescription in October 2018,23 it remains to be seen how and if parents will implement recommended safe opioid practices in the home. Nonetheless, additional studies should examine methods to encourage and enable family engagement with both safe opioid storage in the home and safe opioid disposal/return to pharmacies.

This study has some limitations. This was a single-centre study and our findings may not apply to other pediatric institutions. Nevertheless, our results do suggest a general applicability when compared with available literature. We recruited 110 patients over a time-period of 10,000 procedures; however, many of these were ambulatory and opioids were not prescribed. Additionally, parents may decide not to fill their prescription because of inconvenience or being discharged outside of hospital pharmacy working hours; many surgical patients are also transferred to long-stay rehabilitation facilities. At the time of this study, awareness of opioid safety and stewardship is increasing; and prescribing habits are no doubt changing. For the families who filled out prescriptions for opioids and were not lost to follow-up, we were able to show similar rates of opioid overprescribing and “under-consumption” as reported in international adult and pediatric literature. Our families utilized the services of an in-house pharmacy where pharmacists can contact prescribing physicians to confirm/refine prescriptions; we are uncertain if pharmacists at other pharmacies can take such opioid safety measures. Our study also relied on honest parental self-reporting four weeks following discharge. This approach is often vulnerable to recall bias as parents do not physically check to see how much opioid was left at the time of follow-up. We did ask the parent to retrieve the opioids during the phone call, but this approach is still prone to fabrication in the face of possible misuse or diversion. Finally, our study did not ask families about side-effects or whether their pain was adequately managed with opioids as our goal was to determine the quantity of opioids consumed and the attitudes to storage and disposal after discharge from our institution; assessing the efficacy of pain management was beyond scope of this study.

In summary, our findings confirm and quantify pediatric surgical overprescription of opioids for home use. We showed that 110 families were discharged home with 8,672 MME: 1,416 MME were lost to follow-up and 67% of the remaining opioid (4,829 of 7,256) went unused. At four-week follow-up, 3,781 MME remained in homes. Twenty-two families did not use any of the opioids dispensed on surgical discharge, which accounted for 31% of all MME remaining in the home at four-week follow-up. Those opioids remaining in the home one month after discharge were accessible to others in the home. Given the “epidemic” status surrounding opioid misuse, diversion and deaths,1 it is imperative that prescribed opioids meet but do not exceed post-discharge analgesic requirements at home. Interventions to deliver these goals will improve opioid safety and stewardship in the community for children discharged from surgical care.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Confronting opioids - CDC information and resources on confronting opioid abuse. Available from URL : https://www.cdc.gov/features/confronting-opioids/index.html (accessed February 2020).

Belzak L, Halverson J. The opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Canada 2018; 38: 224-33.

Madadi P, Hildebrandt D, Lauwers AE, Koren G. Characteristics of opioid-users whose death was related to opioid-toxicity: a population-based study in Ontario. Canada. PLoS One 2013; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060600.

Alam A, Gomes T, Zheng H, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Bell CM. Long-term analgesic use after low-risk surgery: a retrospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172: 425-30.

Bicket MC, Long JJ, Pronovost PJ, Alexander GC, Wu CL. Prescription opioid analgesics commonly unused after surgery: a systematic review. JAMA Surg 2017; 152: 1066-71.

Feinberg AE, Chesney TR, Srikandarajah S, Acuna SA, McLeod RS. Opioid use after discharge in postoperative patients: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2018; 267: 1056-62.

Harbaugh CM, Lee JS, Hu HM, et al. Persistent opioid use among pediatric patients after surgery. Pediatrics 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2439.

McCabe SE, West BT, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012; 166: 797-802.

Health Canada. Baseline survey on opioid awareness, knowledge and behaviours for public education research report. Ottawa (ON). Prepared by Earnscliffe Strategy Group for Health Canada; 2017. Available from URL: http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/200/301/pwgsc-tpsgc/por-ef/health/2018/016-17-e/report.pdf (accessed February 2020).

Horton JD, Munawar S, Corrigan C, White D, Cina RA. Inconsistent and excessive opioid prescribing after common pediatric surgical operations. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54: 1427-31.

Garren BR, Lawrence MB, McNaull PP, et al. Opioid-prescribing patterns, storage, handling, and disposal in postoperative pediatric urology patients. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15(260): e1-7.

Whelan RL, McCoy J, Mirson L, Chi D. Opioid prescription and postoperative outcomes in pediatric patients. Laryngoscope 2019; 129: 1477-81.

Sonderman K, Wolf L, Madenci A, et al. Opioid prescription patterns for children following laparoscopic appendectomy. Ann Surg 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003171.

Abou-Karam M, Dubé S, Soriya Kvann HS, et al. Parental report of morphine use at home after pediatric surgery. J Pediatr 2015; 167: 599-604.e1-2.

Wilson AT. Counterfactual consent and the use of deception in research. Bioethics 2015; 29: 470-7.

McPherson ML. Demystifying Opioid Conversion Calculations: A Guide for Effective Dosing. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2009. Available from URL: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/store-files/p1985-frontmatter.ashx (accessed February 2020).

Chen EY, Marcantonio A, Tornetta P 3rd. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge. JAMA Surg 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.4859.

Hill MV, McMahon ML, Stucke RS, Barth RJ Jr. Wide variation and excessive dosage of opioid prescriptions for common general surgical procedures. Ann Surg 2017; 265: 709-14.

Gaither JR, Shabanova N, Leventhal JM. US national trends in pediatric deaths from prescription and illicit opioids, 1999-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6558.

Voepel-Lewis T, Wagner D, Tait AR. Leftover prescription opioids after minor procedures: an unwitting source for accidental overdose in children. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169: 497-8.

Grant DR, Schoenleber SJ, McCarthy AM, et al. Are we prescribing our patients too much pain medication? Best predictors of narcotic usage after spinal surgery for scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98: 1555-62.

Pruitt LC, Swords DS, Russell KW, Rollins MD, Skarda DE. Prescription vs consumption: opioid overprescription to children after common surgical procedures. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54: 2195-9.

Government of Canada. Questions and Answers: Prescription Opioids – Sticker and Handout Requirements for Pharmacists and Practitioners. Ottawa: Health Canada; (updated 7 February 2019). Available from URL: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/applications-submissions/policies/opioids-questions-answers.html (accessed February 2020).

Author contributions

Monica Caldeira-Kulbakas and Conor Mc Donnell contributed to all aspects of this manuscript, including study conception and design; acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafting the article. Renu Roy and Wendy Bordman contributed to the conception and design of the study. Catherine Stratton contributed to the acquisition of data.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding statement

None.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Gregory L. Bryson, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caldeira-Kulbakas, M., Stratton, C., Roy, R. et al. A prospective observational study of pediatric opioid prescribing at postoperative discharge: how much is actually used?. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 67, 866–876 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01616-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-020-01616-5