Abstract

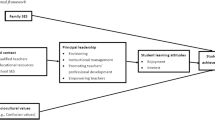

We investigated the relationship between principal instructional leadership and teacher participation in multiple types of professional development in Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. Using the Teaching and Learning International Survey dataset of 2013, we employed two-level logistic regression models to estimate the rigorous effects of principal instructional leadership that were separated out from teacher-level effects. We found that the influence of principal instructional leadership on teachers’ participation in professional development varied across types of learning activities and countries. Our analysis suggests that principal instructional leadership can influence teachers’ participation in mentoring, mentoring, peer observation, and coaching compared to the other types of professional development. Our study builds on and extends research on cross-national characteristics of teacher learning by adding evidence about the relations between principal leadership and teacher professional development in the three Asian countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Researchers have highlighted teacher professional development (PD) as a key to successful school reform and student learning (Darling-Hammond 2005; Desimone 2009; Harris and Sass 2011; Mourshed et al. 2011; Rockoff 2004; Wei et al. 2009). By comparing teacher learning systems internationally, research demonstrates that high-performing countries in international assessments invest more in job-embedded, collaborative, and continuous learning for teachers in addition to rigorous pre-service teacher education programs (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Mourshed et al. 2011; Varkey 2018; Wei et al. 2009). The findings also show their retention rates are higher compared to other countries (see Craig 2017; Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015). In such contexts, developing teachers in their long-term teaching careers is an important issue, and teacher PD becomes central to improving teacher quality. Thus, it is worth exploring how teacher PD works in high-performing education systems to draw implications for leadership practice and policy development.

Importantly, research has indicated that meaningful support from school principals is crucial in promoting teacher learning through PD (Akiba et al. 2015). Recent international trends in teacher PD reflect movements toward community-based and inquiry-oriented approaches, resulting in principal leadership forming learning-oriented school climates (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Hallinger and Walker 2017). However, existing literature contains limited evidence about the influence of principal leadership on diverse types of teacher PD in the global context. Moreover, research findings on high-performing Asian countries have not been widely shared.

This study aims to investigate the relations between principal instructional leadership and teacher participation in PD in Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.Footnote 1 These three Asian countries, where teaching is regarded as a highly respected profession, have established strong career systems and shared norms for PD in teaching (e.g., Akiba 2017; Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Barber and Mourshed 2007; Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Fernandez 2002). In such context, principals take leading roles in navigating and coordinating government-driven policies as well as promoting school-based PD. While researchers have explored teacher PD in these Asian countries, international research tends to overlook the relations between school leaders and teacher PD (Hallinger and Walker 2017). Moreover, studies from each country have suggested similarities and differences in leadership influence on diverse types of teacher PD (e.g., Bjork 2000; Hallinger and Walker 2017; Kim and Kim 2005). To our knowledge, however, rigorous evidence linking cross-national patterns to careful interpretations within specific contexts of each country is scarce. Thus, examining the influence of instructional leadership on teacher learning in these three countries bridges knowledge gaps in instructional leadership in Asian contexts and provides comparative evidence for school reform policies.

We used the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) dataset for these three countries to examine the influence of principal instructional leadership on teacher participation in PD. While some researchers have criticized TALIS approaches for reducing teachers’ voices to data (e.g., Robertson 2012), we acknowledge the usefulness of TALIS to reveal patterns of leadership and teacher PD in these three countries. We carefully selected variables, applied models for each country, and interpreted results based on existing literature about the countries. Focusing on key variables—a composite score of principal perception on instructional leadership and teacher participation in six PD activities—we used two-level logistic regression models to estimate rigorous effects of principal leadership by separating it out from teacher-level effects. We also applied adjusted sampling weights in estimating multilevel models to avoid causing inflated standard errors, which has been overlooked in existing literature using the TALIS dataset for multilevel analyses.Footnote 2

Our primary research questions are as follows:

-

1.

What are the descriptive characteristics of principal instructional leadership and teacher participation in professional development in Japan, Singapore, and South KoreaFootnote 3?

-

2.

To what extent does principal instructional leadership predict teachers’ participation in professional development activities? How does this vary within and across the three countries?

Teacher professional development and principal support

Teacher PD is understood as activities that improve teachers’ knowledge, skills, and attitudes of teaching practices (OECD 2014a). Literature has shown that teacher PD promotes teacher knowledge, skills, and performances (Babinski et al. 2018; Desimone 2009; Garet et al. 2001); teachers’ efficacy (Butler et al. 2015); job satisfaction (Ma and MacMillan 1999); positive school climates (Butler et al. 2015; Hargreaves 2007); and student learning (Jacob et al. 2017; Panero and Talbert 2013). Thus, many school reform movements have viewed teachers’ participation in PD as key to changing teachers’ beliefs and practices, student learning, and the implementation of educational policies (Villegas-Reimers 2003). Given this notion of the importance of teacher PD, this section explores multiple forms of teacher PD and principal support for teacher learning.

Teacher PD activities take various forms. Traditionally, it has been identified as types of official activities or events, such as workshops, conferences, and degree programs (Burns and Darling-Hammond 2014). However, some researchers have suggested that out-of-school programs are limited in their link between teacher learning and actual practices in schools (Desimone 2009; Villegas-Reimers 2003). Studies have argued that successful teacher PD is job-embedded, collaborative, and sustaining, and have suggested alternative ways of teacher learning (Desimone 2009; Desimone and Pak 2017; Gersten et al. 2010; Guskey 2002; Wei et al. 2009; Zepeda 2015). One representative example is learning through professional learning communities (PLCs) where teachers acquire knowledge and practices through interactive learning with school members, which in turn improves student learning (Hord 1997; McLaughlin and Talbert 2006; Stoll and Louis 2007). In this context, researchers have conceptualized “teacher” as knowledge generator, reflective practitioner, and researcher (Hargreaves and Fullan 2012; Horn and Little 2017).

In alignment with this, scholars proposed different approaches to teacher PD, like teacher collaborative inquiry (e.g., Donohoo 2013) and lesson studyFootnote 4 (e.g., Lewis et al. 2006). Teacher collaborative inquiry emphasizes a link between teacher inquiry and instructional problem-solving (Donohoo 2013; Butler et al. 2015). Similarly, lesson study focuses on teacher learning through collaborative planning, observation, and reflection (Hiebert and Stigler 2017; Lewis et al. 2004, 2006). In these forms of PD, teachers’ learning activities are not limited to their schools. Teachers can observe classroom teaching in other schools and share lesson reflections with other teachers (Lewis et al. 2006). When collaborative inquiry is initiated at the district level, school networks formed by district efforts can help teachers participate in learning with teachers in other schools (Butler et al. 2015). Moreover, research focusing on teachers’ individual needs has also indicated mentoring and coaching as effective ways of PD to meet teachers’ particular needs and provide personalized support (Aspfors and Fransson 2015; Collinson et al. 2009; Desimone and Pak 2017). With the growth of various types of teacher learning, recent literature suggests different forms of PD activities vary in impact depending on program content, providers, and scales (Hill et al. 2013).

While teacher PD takes different forms, an extensive body of research has suggested the importance of resources and support for successful teacher PD (Akiba et al. 2015). Akiba et al. (2015) found that teachers who received increased levels of organizational resources—human resources (access to knowledge), material resources (money and time), and social resources (learning communities)—were more likely to participate in teacher PD activities. Regarding organizational resources, school principal leadership plays a direct and indirect role in providing and coordinating support for teacher PD (Coburn 2001; Marks and Printy 2003; Talbert et al. 2010). School principals as instructional leaders are responsible for arranging teacher PD opportunities, providing appropriate resources, and setting priorities for teacher learning (McLaughlin and Talbert 2006; Printy 2008; Stein and Nelson 2003). Yet, limited empirical evidence exists regarding whether school principal leadership indeed increases teachers’ participation in PD. Additionally, leadership effects can differ depending on types of PD. Furthermore, few studies have examined the link between school leadership and teacher PD with a comparative perspective in Asian contexts, while international scholars have attended to teacher PD in multiple countries.

Principal instructional leadership for teacher professional development

Principals’ influences on teacher learning are well documented in literature on instructional leadership. The concept of instructional leadership was developed through the effective school movement of the 1980s and assumed school principals were essential to promoting teacher knowledge about student learning (Marks and Louis 1997; Marks and Printy 2003). The conceptualization of instructional leadership has evolved from direct, authoritarian perspectives to indirect, collaborative perspectives. This reconceptualization aligned with the movement to professionalize teaching.

In earlier work on instructional leadership, Hallinger and Murphy (1985) conceptualized instructional leadership proposing three dimensions: (1) setting school missions—setting clear school goals; (2) managing instructional programs—evaluating instruction, coordinating curriculum, and student learning; and (3) creating positive school climates for learning—promoting teacher PD, maintaining high visibility, and using incentives for teachers and learning. Echoing these three elements, Murphy (1990) added another dimension of creating a supportive work environment. Thus, instructional leadership focuses on principals’ responsibilities in facilitating teachers’ instructional tasks and practices (Hallinger 2005).

Under the teacher professionalization movement, researchers have criticized the traditional concept of instructional leadership because the literature described principals as authoritarian and teachers as docile, passive followers (Sheppard 1996; Marks and Printy 2003). Marks and Printy (2003) proposed the idea of shared instructional leadership that promotes interactive and collaborative relationships between principals and teachers. Shared instructional leadership is defined as a “synergistic power of leadership shared by individuals through the school organization” (Marks and Printy 2003, p. 393). Literature on shared instructional leadership (e.g., Marks and Printy 2003; Printy et al. 2009) illustrates five core behaviors: (1) principals exert strong leadership to facilitate teacher growth and direction; (2) principals offer opportunities for teacher growth; (3) principals discuss alternatives for instructional practices with teachers; (4) principals maintain cohesion of educational program; and (5) teachers are responsible for change and leadership roles among themselves (Urick and Bowers 2014). While shared instructional leadership has commonalities with the earlier instructional leadership models, it focuses more on principals’ indirect influences on teacher growth by engaging teachers in their own professional growth and promoting teacher leadership.

Principal instructional leadership and teacher PD in Asia

High-achieving countries in Asia (e.g., Japan, Singapore, and South Korea) have recently received increasing attention from policy makers to investigate evidence for setting political agendas around “best practices” and solutions to local problems (Akiba 2017; Hiebert and Stigler 2017). Global policy agendas have focused on teacher quality, and teacher reforms in Asian countries have conceptualized teachers’ participation in teacher PD as a requirement and a shared norm in the teaching profession. While many cross-national studies have examined teacher learning and its contexts, how principal leadership supports teacher PD in Asian countries has not been widely shared internationally, compared to other contextual factors.

An extensive body of research on instructional leadership has been theorized in Western contexts (Hallinger 1995; Hallinger and Walker 2017), and literature on leadership for teacher learning in Asian countries has applied similar concepts and theories from Western literature. However, origins of theories closely align with each society’s historical and social contexts. Thus, instructional leadership literature in Asian contexts sheds light on similarities and differences in theoretical conceptualizations and practices across cultures (Hallinger and Walker 2017). Compared to Western literature, Hallinger and Walker (2017) discovered distinctive features of principal instructional leadership in five East Asian societies (China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam). First, school principals have a narrow zone of setting missions and goals under national education policies. Second, principals implement school curricula guided by national curricula and often use the strategy of distributing instructional leadership responsibilities in schools. Third, principals introduced PLCs in schools and saw managing relationships as key to facilitating PLCs. They also encouraged teachers’ participation in PD. Thus, instructional leadership behaviors in Asian contexts illustrate guiding school instruction under national policies and supporting teacher learning by forming learning climates in schools (Hallinger and Walker 2017).

These features of instructional leadership closely relate to teaching profession contexts in society. Especially in countries like Japan, Singapore, South Korea, where teacher retention is relatively high, school leadership roles are part of the teaching career ladder. Thus, teachers are viewed as potential school leaders and become school principals after accumulating experience in teaching (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Bjork 2000; Kim and Kim 2005). In this context, school principals and teachers share a norm that teacher PD is part of career development in the profession. Additionally, education policies supporting teacher PD have established structured resources for teacher learning. Utilizing district, provincial, and national policy resources, principals coordinate and support school-based professional learning for teachers. Thus, school principals tend to take roles of facilitator or coordinator in teacher PD rather than instructor or director.

Teacher PD policies and principal instructional leadership in Japan, Singapore, and Korea

While research has identified commonalities of instructional leadership and teacher PD in Asia, the findings also reported differences across countries. As comparative education literature has suggested, teaching and leadership reflect societies’ historical and cultural contexts (e.g., Hallinger and Walker 2017; Montecinos et al. 2018). Thus, we explore an overview of the teacher PD policies and the research findings about principal instructional leadership and teacher PD from each country.

Japan

Teaching, as a respected profession in Japan, requires continuing PD (NCEE 2019). Each local board of education determines the required minimum yearly hours of PD for individual teachers, and institutions at the local, prefectural (state), and national levels offer specific PD programs for teachers. In 2009, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Ministry of Education here after) launched a new plan for renewing teaching certificates: every 10 years, teachers must participate in 30-h formal PD to prove their teaching practices are up-to-date in order to renew their licenses. These courses are offered by universities with an approval from the Ministry of Education (Akiba 2013; Ministry of Education 2010; NCEE 2019).

While the formal PD is required, teachers often participate in informal PD through “lesson study” (Akiba 2013; Lewis et al. 2004; NCEE 2019; Hiebert and Stigler 2017). Lesson study is a system for improving teaching via collaborative efforts between teachers and administrators (Lewis et al. 2004). School principals organize meetings where teachers with various levels of experience collaboratively develop a lesson plan, identifying their classroom needs and utilizing research interventions. One teacher uses this lesson plan in his or her classroom practices and other teachers observe the lesson. After the sample lesson, teachers and principals meet again to discuss and reflect how to improve the lesson plan. Throughout this informal PD, teachers establish shared goals, develop curricula, and evaluate outcomes that provide feedback for teachers. It is common for teachers to collaboratively observe lessons of both colleagues and teachers in other schools (Lewis et al. 2004, 2006). Thus, teachers take leadership roles within this collaborative learning system, and principals provide structural support like financial resources, time arrangement, and normative support to promote learning-oriented climates.

While Japanese teaching practices have received international attention through the cross-national PISA-Video study and lesson study movements, researchers’ attention to school leadership has been relatively low (Bjork 2000). As literature on Japanese lesson study has highlighted, collaborative learning opportunities among teachers within and between schools are common in Japan. According to OECD (2014c), Japanese teachers reported high levels of PD participation, but a large portion of teachers reported conflicts with their work schedules regarding participation in PD. We assumed that principal leadership is critical in managing these barriers to help teachers engage in diverse types of PD in Japan.

Qualitative studies provide more details about principal roles in the Japanese context. Bjork’s (2000) interview study about Japanese principals’ role in PD efforts suggested that, compared to American principals, Japanese principals tended to emphasize administrative efforts as opposed to “hands-on” instructional approaches for teachers. Bjork (2000) pointed out several factors to explain this phenomenon. First, expectations for public school community as a “moral community” (Shimahara 1991, p. 272) followed by intense scrutiny from insiders and outsiders led principals to avoid conflict and seek harmony. Second, promotion to administrator meant parting from classroom teaching to center on managerial work. Third, all teachers are actively involved in school management processes, and experienced teachers led committees; this empowered teachers to view themselves as critical actors in school governance. Bjork (2000) asserted that these environments tended to center teacher PD in development and put principal leadership on the periphery. However, the study reported young principals used more hands-on approaches in facilitating teacher PD. Chen et al.’s (2017) comparative study about Japanese and Taiwanese principals implied that principals in Japan are more willing to intervene to facilitate teacher learning. They found Japanese principals’ instructional leadership favors supporting teacher professionalism and employing team leadership, while Taiwanese principals focus more on student performance. In sum, it is assumed that, even though teacher PD is not the top priority for Japanese principals, they cultivate teachers’ desires to achieve successful learning through PD. They also value teaching as professional practice by providing leadership roles for teachers and coordinating resources to support teachers’ learning opportunities.

Singapore

Singapore teachers have a wide range of PD opportunities supported by the government. Since the government initiated the national policy “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation” that highlighted education as a life-long process and the importance of creative thinking skills (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015), the Ministry of Education has launched policies to facilitate continuing teacher PD as a means to improve education quality, such as “Teach Less, Learn More” (MOE 2005) or “Teacher Growth Model” (MOE 2012). With these policies, teachers are encouraged to continue to their learning by participating in multiple PD platforms—in-person and online courses, workshops, and graduate degree programs, conferences, mentoring and coaching, and school–university partnerships (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; NCEE 2019). Teachers can attend PD for 100 h per year (optional), and most teachers take advantage of multiple PD programs based on their needs (Wong 2013). The National Institute of Education (NIE) and the Academy of Singapore Teachers (established by the Ministry of Education) offer diverse PD programs including formal teacher trainings. In addition, teachers have enormous opportunities to learn through school-based PD activities. At the school level, administrators and teacher leaders develop their yearly PD agenda based on the needs of the school and teachers as well as demands from the national curriculum (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015). Notably, the Ministry of Education fully subsidizes the cost of teacher PD, and schools have their own approval processes in terms of whether PD programs taken by the teachers are relevant (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Wang et al. 2014).

As above policies suggest, Singapore has one of the most fully developed career ladder systems for classroom teachers (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Nguyen and Ng 2014). This system includes the leadership track (e.g., principal, director), the teaching track (e.g., lead teacher), and senior specialist track (e.g., lead specialist). Under this structure, teachers often take leadership roles to support instructional programs and principals are responsible for providing leading opportunities for their teachers. Although national policies and curricula set boundaries for principals’ leadership influence, principals in Singapore—compared to other Asian countries—have relatively more freedom to develop visions for their schools (Hallinger and Walker 2017).

Nguyen et al. (2017) found that Singapore principals’ articulations of their visions for PD had an indirect impact on teacher development in schools. In their study, principals provided essential guidance for teachers in deciding career paths and participating in personalized PD. Furthermore, principals concentrated on structuring mentoring for all novice teachers by engaging other teachers as formal peers. Notably, the authors suggested large school size and structured career policies encourage principals to use shared and indirect instructional leadership strategies in Singapore. In processes of instructional leadership within schools, Nguyen et al. (2017) revealed that hierarchy and heterarchy elements coexist. That is, Singapore principals provided school visions and directions to teachers through the hierarchical structure and, within this, instructional leadership was distributed by teacher leaders. Hairon and Dimmock (2012) also highlighted hierarchies in cultural and institutional contexts affect learning communities in Singapore schools. This finding supports the typology, what Nguyen et al. (2017) called “heterarchy nested in hierarchy” in school PD structures (p. 161). These findings infer that Singapore principals support teacher PD participation by shaping school goals for teacher learning and coordinating learning opportunities for teachers given the structured teacher development system.

South Korea

The teacher status and hiring systems in South Korea rely on national laws specifying hiring processes, appointing, PD, and promotions to administration.Footnote 5 Teacher appraisal and promotion policies are founded on laws promoting participation in PD at least 60 h per year, but teachers tend to spend more than 60 h for PD to attain full credits for teacher evaluation and teacher performance pay. Korean teachers participate in required formal PD for their qualifications or promotions, and they also participate in multiple types of PD voluntarily for their own needs to grow. For example, after three or more years of teaching experience, teachers need to take a 180-h PD program offered by education training institutes associated with Offices of Education at the province (municipal) level (Ministry of Education 2016). In addition to these formal PD opportunities, multiple teacher training institutions approved by the Ministry of Education provide various types of programs including online modules, long-term workshops, and school-based professional learning activities. Guided by national or provincial policies, teachers are sometimes requested to participate in specific trainings; beyond this, Korean teachers actively participate in a broad range of PD (NCEE 2019).

With the initiative of a form of teacher evaluation policy, “Teacher Competence Development Assessment” in 2010, the results of teacher performance evaluated by teacher peers, school leaders, students, and parents inform individualized PD plans (Mullis et al. 2016). In addition, teachers can have special PD opportunities, such as research sabbaticals or study abroad. Recently, the Korean government has promoted teacher-led, school-based PD to promote national curriculum as well as teacher quality. According to the national PD plan developed by the Ministry of Education, principals are expected to support teacher PD by recommending specific programs and using funding to finance teacher PD. Most PD programs offered by the government institutions are subsidized, and teachers have a certain amount of financial support to participate in PD (including programs offered by private providers) (NCEE 2019).

In addition to such policy efforts to support teacher PD, research has shown that various types of school-based PLCs spread via bottom-up efforts of teacher communities in Korea (Lee and Kim 2016). In this context, principals may have several reasons to encourage teacher participation in PD opportunities: to meet policy requirements, to achieve school organizational goals, and to support individual teachers’ career development.

In Korean contexts, several large-scale quantitative studies have examined the relationships between principal instructional leadership and teachers’ professional collaborations using hierarchical linear models (Park and Ham 2016; Park 2012). Park and Ham (2016) found the congruency of principal–teacher perceptual agreement on principal leadership is positively associated with teachers’ collaborative interactions. Park (2012) analyzed teacher and principal survey data from vocational high schools and suggests that principal leadership roles as initiator and manager (rather than responder) can help create climates that enhance innovation.

In addition to these quantitative findings, a qualitative meta-analysis about Korean teacher learning communities found conflicting results regarding the effects of administrative support on teacher learning communities (Lee et al. 2015). For example, districts’ financial support and monitoring can promote learning communities, but too much intervention from local and national education authorities can demotivate and manipulate teachers' autonomy for their learning (Lee et al. 2015). They showed that, depending on school contexts (e.g., school size, elementary or secondary), teachers sought different programs based on their needs (e.g., consulting with external experts in a small school). Similarly, Seo (2008) found strong incentive policies for teacher PD resulted in forced collaboration in out-of-school teacher learning communities and teachers’ diminished agency regarding participation in PD. Research findings suggest Korean principals play critical roles in forming learning-oriented school climates and coordinating resources for teacher PD within policy-driven environments.

Summary

Compared to western perspectives on instructional leadership, literature in these Asian countries has revealed that instructional leadership in Asia takes more indirect approaches. For example, school principals arrange resources within and between schools in accordance with district or national policies by introducing outside school PD opportunities and encouraging teachers to lead PD within schools. This contrasts to the more hands-on styles frequently found in Western contexts (e.g., principals leading PD within schools or giving direct feedback on teachers’ classroom practices). Additionally, school principals in these three countries are likely to have more concerns about managerial tasks than teacher instructional quality (e.g., Bjork 2000) due to governmental controls in pre-service education and teaching job certifications. Teachers in the three countries have rigorous pre-service teacher education before they enter their teaching jobs. In addition, higher teacher retention rates would enable schools to have more experienced teachers; therefore, utilizing instructional expertise from teacher leaders is more useful in supporting teacher learning. Thus, instructional leadership in these three Asian contexts suggests that principals’ instructional leadership affects teacher PD by mediating policy influences and supporting the needs of teachers to grow.

Methods

Data and sample

This study used a dataset of the 2013 Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) conducted by OECD.Footnote 6 TALIS is an international, large-scale survey that provides information on teachers’ learning environments and working conditions in schools across 34 countries (OECD 2014b). TALIS aims to offer valid, timely, and comparable evidence to help countries review and determine policies for developing a high-quality teaching profession. Our selected dataset included lower-secondary education level principal and teacher surveys from Japan, Singapore, and South Korea. TALIS sampling employed a two-stage stratified sampling design, which first sampled schools with probability proportional to the size (PPS) of teachers, and then randomly sampled a fixed number of teachers within selected schools.Footnote 7 The original samples in the dataset representing each target population were 3484 teachers across 192 schools in Japan; 3109 teachers across 159 schools in Singapore; and 2933 teachers across 177 schools in Korea.

Measures

Outcomes

In the teacher survey items, teachers were asked “During the last 12 months, did you participate in any of the following professional development activities?.” To compare different approaches to teacher professional development, we chose six types of activities from TALIS: (1) courses and workshops (PD1: workshop); (2) education conferences or seminars (PD2: conference); (3) observation visits to other schools (PD3: visit); (4) a network of teachers (PD4: network); (5) individual or collaborative research (PD5: research); and mentoring and/or peer observation and coaching as part of a formal school arrangement (PD6: mentoring). These variables were considered as our primary outcome variables for each model. The six activities were dichotomously coded as “1” if a teacher participated in that particular activity, and “0” if not.

Relying on Desimone (2009) and Desimone and Pak (2017), we presumed the latter four types of activities as relatively closer to characteristics of effective forms of PD, and the first two types of activities are often regarded as conventional forms of PD. We thus classified these six activities into two categories: traditional types of professional development (courses/workshops and conferences/seminars) and practice-based types of professional development (observational visits, networks, research, and mentoring/coaching). We hypothesized that the relationship between principal leadership and teacher participation in professional development would differ across countries depending on activity type.

Primary predictor

For principal instructional leadership, we used a scaled factor score from TALIS measured by the following three items: (1) “I took actions to support co-operation among teachers to develop new teaching practices”; (2) “I took actions to ensure that teachers take responsibility for improving their teaching skills”; and (3) “I took actions to ensure that teachers feel responsible for their students’ learning outcomes.” We used the composite scaled score estimated by TALIS instead of using original items to avoid potential risks in validity for the measure of latent factor scores in a context of comparative studies. According to TALIS 2013 Technical Report (OECD 2014b), composite factor scores were estimated using multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) with taking into account stratification and cluster effects. TALIS 2013 confirmed the approximate measurement invariance across countries (OECD 2014b), enabling us to use the factor scores for comparisons.

Covariates

This study controlled for teacher- and school-level variables that we hypothesized are related to all the types of PD activities. We examined their correlation estimates without sampling weights (because the correlation analysis is based on single-level analysis), and then we included those that were statistically significant with at least one of PD activities among six. Since this study is to explore different patterns of three countries, the statistical modeling procedure is inherently exploratory. Nevertheless, as previous studies indicated, it is important to control various forms of organizational resources—human, material, and social—and individual teachers’ backgrounds that influence their participation in PD (e.g., Akiba et al. 2015). We considered three domains of covariates as follows.

First, teacher-level covariates include (a) gender; (b) permanent employment status; (c) years of working experience; (d) teaching time per week; (e) need of PD for teaching for diversity; (f) need of PD in subject matter and pedagogy; and (g) teaching STEM subjects.Footnote 8 Research findings suggest that these teacher-level variables are considered to be associated with teachers’ PD activities (e.g., Akiba and LeTendre 2009; Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Lee and Kim 2016; Torff and Sessions 2008). Specifically, teachers with a permanent employment status are more likely to participate in certain types of PD, partly because of guaranteed financial aid or policy mandates in these countries (e.g., Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Lee and Kim 2016). However, mentoring or observation visits can be open to all of the teachers, regardless of their job security status, which could result in different patterns of association with PD activities. Likewise, years of experience in teaching, teaching time, and their perceived need of PD for diversity, subject, and pedagogy are highly related to their actual participation in PD (e.g., Akiba and LeTendre 2009). Because a large portion of traditional PD activities in three countries were designed for STEM area (for secondary school-level teachers), we also included whether or not the teacher teaches STEM subjects. We hypothesized that teachers in non-STEM subjects can have a lower probability to participate in the traditional PD compared to the other types of PD.

Second, we added school-level background characteristics including (a) school type (public or private); (b) school location; (c) school size; and (d) student–teacher ratio. These variables are considered organizational material resources that can be associated with teacher PD participation (e.g., Akiba et al. 2015). For instance, schools located in metropolitan areas are more likely to have access to teacher networks and research opportunities affiliated with universities or organizations that support teacher PD, potentially leading teachers to participate in certain types of PD activities. These school-level characteristics are usually fixed effects for which the principals cannot control. Assuming that they are independent of principal instructional leadership, we controlled for the effects of these variables in our model to clarify the effect of the principal instructional leadership.

Third, characteristics of principals and school climate were controlled: (e) years of working as a principal; (f) mutual respect; (g) lack of pedagogical personnel; and (h) lack of material resources (e.g., Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Horn and Little 2017; Postholm 2012). After the exploratory analyses among the variables, we hypothesized that principals with more experiences as a principal have more impacts on teacher PD activities. In addition, research has shown that school climate, such as the shared norms around mutual respect, is critical in forming and implementing school-based PD activities (Horn and Little 2017; Postholm 2012). We also controlled for the shortages of human and material resources because teacher PD policies in these countries suggest that lack of pedagogical personnel and material resources can hinder teachers’ participation in PD (e.g., Mullis et al. 2016). How we treated and recoded those variables is presented in online Appendix (please see for details).

One of the limitations of our modeling approach is that we were not able to include policy-related variables, such as mandatory PD hours or certain types of PD required by the governments because the TALIS dataset did not provide this information. Therefore, it is important to note that the factors regarding different polices among these countries are omitted in our model; therefore, interpretation of the results should be done carefully. However, we want to point out that this limitation stems from the data we use, not from our model and analysis.

Analytic strategies

Since teachers are nested within schools and the dependent variables are binary, we employed two-level logistic regression models for analyses. The models for each of the six activities in three countries were estimated separately (6 × 3 = 18 final models). First, we fitted unconditional models to examine whether the average participation rate in each activity differs between schools, which is a random effect of the intercept in model. The two-level unconditional logistic model can be represented at each level as follows:

Level-1 (teacher):

Level 2 (School):

In this model, \(Y_{ij}\) is a dichotomous outcome of participation in a PD activity of teacher i in school j, and \({\text{P}}\left( {Y_{ij} = 1} \right)\) is a probability of participation in a PD activity. \(\beta_{0j}\) is the intercept for cluster j. With no given predictors in this unconditional model, \(\gamma_{00}\) is an average probability of participation in a PD and \(u_{0j}\) is the level-2 random effect, which is variance of the intercept indicating a difference between schools.

After estimating the unconditional models, we further added teacher- and school-level predictors. \({\text{P}}\left( {Y_{ij} = 1} \right)\) is transformed through logit link function into the odds of participation. All predictor slopes were treated as fixed due to small outcome variations between schools in the three countries. We also assumed that the effects of predictors on outcomes would not significantly differ across schools. All variables were included without any centering techniques due to complexity of interpretation for the binary outcomes with multiple predictors. Our full conditional model including both teacher- and school-level predictors is represented as follows:

Level-1 (teacher):

Level 2 (School):

Weights

Since TALIS 2013 uses a stratified two-stage probability sampling design that sampled schools firstly with unequal probabilities of selection and then teachers, there are two kinds of weights in the available dataset: final teacher weights (TCHWGT) and final school weights (SCHWGT). The final TALIS 2013 weights were calculated as the product of a base weight and one or many adjustment factors at each level (OECD 2014b). These weights reflect the inverse of the probability of ultimate selection, factors of clustered sampling, corrections for non-response, and oversampling. In fitting multilevel models with weights, it is crucial to use both level of weights in the estimation to get unbiased estimates with corrected sampling errors (OECD 2014b; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal 2006; StataCorp 2015). It is also important to note that final teacher weights are unconditional weights that include final school weight in the calculation with both teacher base weight and adjustment weights (OECD 2014b). Therefore, we used rescaled weights for estimation—conditional teacher-level weights, which are teacher-level weights divided by school-level weights.Footnote 9 All analyses were done using STATA 14.2 (StataCorp 2015).

Results

Descriptive characteristics

Descriptive statistics in Table 1 show characteristics of teachers’ participation in PD and principal instructional leadership in each country (research question 1). Regarding patterns of teachers’ participation in different types of PD activities, we first found that most teachers across countries participated in workshop activities (PD1) compared to the other five types of PD activities (60% in Japan, 93% in Singapore, and 78% in Korea). Second, over half of teachers in Japan (57%) and Singapore (62%) and 45% of Korean teachers reported conference participation (PD2). Third, over half of teachers in Singapore (54%) and Korea (54%) participated in teacher networks (PD4) and mentoring (PD6). However, in Japan, a relatively lower percentage of teachers participated in these two activities (23% in PD4, 30% in PD6). Similarly, for research-oriented activities (PD5), 46% of Singapore teachers and 43% of Korean teachers reported participation, while 23% of Japanese teachers reported attendance. Fourth, while 52% of Japanese teachers participated in observation visits to other schools (PD3), 23% and 31% of teachers reported participation in Singapore and Korea, respectively. Regarding teacher characteristics, we found that, on average, Singapore teachers have less years of teaching experience (9.62) than Japanese (17.47) and Korean (16.44) teachers, respectively. This is due to the Singapore career ladder system in which teachers decide their career path tracks (administrators, teacher leaders, and specialists) after the first five years of teaching (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017).

Regarding instructional leadership, Singapore had the highest score (12.08) followed by Korea (11.57) and Japan (9.17). This might correlate with principals’ total years of working. On average, Singapore principals had 7.54 years of experience while Korean and Japanese principals had 3.43 and 4.77, respectively. Japanese principals reported the highest dissatisfactions in pedagogical (0.93) and material resources (0.56), meaning they had the most difficulties (0: not a problem, 1: problem) in terms of school resources, compared to the other two countries. Interestingly, 93% of Japanese principals thought they had problems with securing pedagogical resources, while 67% of Singapore and 57% of Korean principals agreed on having problems. In terms of student ratio per teacher in schools, Japan had the highest number (24.90), followed by Korea (18.68) and Singapore (14.05). In short, Japanese principals had more difficulties with human and material resources, and had shorter years of leadership experience working as principals.

Principal instructional leadership and teacher professional development participation

To answer the second research question regarding the effects of principal instructional leadership on teachers’ participation in PD, we report results for each PD activity and examine them by country.Footnote 10 We first present our results for the traditional types of PD (courses/workshops and conferences in Table 2) followed by results for practice-based PD (visit, network, research, and mentoring in Table 3). We will present the notable effects of covariates on teachers’ participation in PD because we believe these results can help us understand how instructional leadership is associated with our outcomes. At the end of this section, we provide a comparison of instructional leadership effects on participation in six PD activities across countries.

Traditional types of professional development

Table 2 shows odds ratio (OR) estimates from the two-level logistic regression models for traditional types of PD. We found principal instructional leadership is a statistically significant predictor of teachers’ participation in traditional types of PD in Japan. For example, in Japan, for every one-point increase in principal instructional leadership, the odds are about 1.08 greater for teachers who attended workshop activities compared to teachers who did not. Similarly, principal instructional leadership is positively associated with teachers’ participation in conferences in Japan (OR = 1.07). While the coefficients of instructional leadership were similar to 1 in Singapore and Korea, these odds ratio estimates were not statistically significant.

Across all models, we found permanent teachers have significantly higher odds of attending traditional types of PD. Being female showed significantly lower odds of participation in conferences in Japan and Korea (OR = 0.85 in Japan, OR = 0.74 in Korea), but it showed significantly higher odds of attending workshops in Japan (OR = 1.25). Teachers’ years of working was positively associated with attending workshops and conferences in Korea, but was negatively associated with workshops in Singapore. Teachers committed to teaching for diversity were more likely to attend traditional types of PD in Korea (PD1, PD2) and Japan (PD2). The coefficients of teachers’ needs for subject education were above 1 in all six models, but were statistically significant only in Japan (PD1, PD2). Interestingly, STEM teachers in Singapore showed a negative relation with participation in conferences (OR = 0.67), unlike the other two countries.

Regarding school characteristics, we found more significant relations between school factors and teachers’ participation in PD in Japan. Public schools and school size in Japan were significant predictors of teachers’ participation in workshops and conferences. School mutual respect was negatively related to both PDs in Japan, but was positively associated with conferences in Korea.

Practice-based professional development

Table 3 shows the odds ratio (OR) estimates from the two-level logistic regression models for practice-based PD. Among the four PD activities, principal instructional leadership predicted higher odds of mentoring in the three countries (OR = 1.11, 1.04, and 1.07 in Japan, Singapore, and Korea, respectively), while that of Singapore was not statistically significant. Coherent relations between instructional leadership and practice-based PD across the models were not found in the five other types. These relations showed differences between countries. For example, the odds ratios of instructional leadership in Japan were all above 1, but those of visits in Singapore and those of network and research in Korea were below 1, all of which were not statistically significant.

For teacher-related characteristics, being female predicts lower probability of participation in practice-based PD activities in general compared to being male. For example, in Singapore, a female teacher was 0.62 times as likely as a male teacher to attend observation visits in other schools. We found permanent teachers have significantly higher odds of attending most practice-based PD. Additionally, years of working as a teacher showed positive relations with teachers’ participation in network, research, and mentoring PD activities (all are statistically significant except research-oriented PD in Korea). Teachers’ need of teaching for diversity and subject education predicted higher odds of teachers attending practice-based PD activities in Japan. This trend was found in several models in Singapore and Korea. Therefore, it can be understood that higher needs for teaching predict greater probability of participation in practice-based PD; moreover, its relations were strongest in Japan.

Regarding school characteristics, we found more significant predictors for practice-based PD compared to results for traditional PD. Working at public schools versus private schools predicted teachers in public schools were more likely to attend practice-based PD activities in Japan and Korea, in general. Notably, in Japan, public school teachers were 5.35 times more likely to participate in observation visits. School location in metro areas was positively associated with observation visits and mentoring in Korea. The odds of years working as a principal were slightly above 1 in most practice-based PD models, and were statistically significant for network-based PD and research-oriented PD in Korea. Mutual respect was positively associated with network PD in Korea but was negatively associated with research-oriented PD in Singapore. Regarding lack of school resources, coefficients in Korea were all above 1, unlike the other two countries. The relations between lack of pedagogical personnel and mentoring (OR = 1.35) and relations between lack of material resources and observation visits PD (OR = 1.52) were statistically significant. This means, in Korea, teachers from schools that have more difficulties in teacher recruitment and instructional materials are more likely to predict participation in practice-based PD compared to teachers from schools with enough resources.

Summary

The effects of the principals’ instructional leadership on the six activities across countries are presented in Table 4. In Japan, instructional leadership effects showed positive relations with all types of PD, but was statistically significant only for workshops, conferences, and mentoring types. In Singapore, principal instructional leadership was not statistically associated with all activities, holding all other variables constant. In Korea, it was positively associated with participation in mentoring. Overall, instructional leadership was positively associated with the probability of teachers’ participation in mentoring in the three countries. Although Singapore’s result was not significant, the coefficient was above 1.

Discussion

Our findings showed that a high ratio of teachers in the three countries participated in the traditional types of PD, such as courses and workshops, as dominant forms. We also found over half of the teachers in each country participated in research-oriented PD, teacher network-based PD, and coaching and/or mentoring, supporting previous research findings that suggested the emergence of PLCs in these countries (Hairon and Dimmock 2012; Lee and Kim 2016). Regarding country-specific differences, in practice-based PD, higher portions of Japanese teachers participated in observation visits to other schools, while Singapore and Korean teachers centered more on teacher networks, research-oriented activities, and mentoring and/or peer observation and coaching. This shows that the countries may exhibit a unique trend in teachers’ PD participation. As the existing literature noted (e.g., Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Lewis et al. 2004; Lee and Kim 2016), national teacher PD policies can promote a particular form of PD in each country. Our results can be explained by the fact that teachers in a certain country are familiar with adopting a certain type of PD, correlating with teacher PD policies and cultural characteristics in the teaching profession. For example, in Japan, lesson study has been historically popular for teachers; therefore, schools can be more open to having teachers visit in other schools and sharing their classroom practices with them as part of lesson study activities (Akiba et al. 2015; Lewis et al. 2004).

In terms of principal instructional leadership effects, while many of the relations between instructional leadership and teacher participation in PD activities were not significant, our analysis shows that instructional leadership in Korea and Japan was positively associated with the probability of teachers’ participation in PD6 (mentoring, peer observation, and coaching). Although Singapore’s result was not significant, it still showed the same direction as that of Korea and Japan. This result supports other research findings that highlighted the critical role of school leaders in school-based teacher PD that may include mentoring, peer observation, and coaching (e.g., Hallinger and Walker 2017; Lewis et al. 2004, 2006; Nguyen et al. 2017; Park and Ham 2016). Since the teachers were asked whether they participated in PD6 as part of a formal school arrangement, principals may initiate plans and coordinate resources to arrange mentoring, peer observation, and coaching for their teachers. Thus, principal leadership can have more influence on teachers’ participation in this type of learning compared to the other types of PD.

However, this relationship was not significant in Singapore. One way to explain this finding is that, in Singapore schools, a school staff developer and a team of teacher leaders are responsible for determining needs of school-based PD plan and support teachers learning (Bautista and Ortega-Ruiz 2015; Darling-Hammond et al. 2017); therefore, the principal leadership effects on teacher PD may not be as strong as those in Japan or Korea. In addition, individual teachers are responsible for their own PD plan and can find multiple PD opportunities through the cluster system, a network of 10–13 schools (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017), which may lead to the result that principal instructional leadership was not significantly related to teachers’ participation in the six PD activities in Singapore.

Across the six PD types, each country showed different patterns of instructional leadership effects. Especially in Japan, principal instructional leadership was positively associated with the likelihood of teachers participating in three types of activities: workshops, conferences, and mentoring. However, in Singapore, any relations between principal leadership and PD participation were not statistically significant. In Korea, principal instructional leadership significantly increased the probability of teachers’ participation in mentoring. This might be related to policy influences in each country. For example, in Singapore and Korea, as national policies established requirements of PD in their career ladder systems, principal instructional leadership might have little impact on teachers’ decisions regarding PD participation. This finding is supported by the results from Nguyen et al. (2017). As discussed in the background literature, vertical and horizontal relationships in instructional leadership structures within Singapore schools (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Nguyen et al. 2017) might make it possible for teachers to be more influenced by their colleagues and teacher leaders than their principals. In addition, school level (lower-secondary) can explain weak relationships between principal instructional leadership and teacher PD participation. Research suggests, lower-secondary school teachers have less influences from principals in developing their instructional practices compared to primary school teachers because of subject department division (Heck 1992; Louis et al. 2010).

Moreover, these results can be associated with each country’s teacher and school characteristics. Compared to other countries, Singapore teachers had high rates of attendance in courses and mentoring for PD; this could be related to their relatively shorter teaching experiences. Japanese teachers’ active participation in visiting other schools can be explained by their lesson study tradition of the country. It may be possible that lesson study in Japan is frequently practiced through visiting other schools and, therefore, even though lesson study involves research and network-oriented learning opportunities (Lewis et al. 2006, 2006), Japanese teachers are likely to recognize lesson study as the category of visiting other schools. The smaller size of Japanese schoolsFootnote 11 compared to the other two countries may explain the high rates of teachers visiting other schools because teachers in small schools might not have enough human resources to provide appropriate knowledge and skills within their schools. For example, in secondary schools, collaborations with teachers teaching the same subject are important; thus, teachers in small schools are more likely to reach out to teachers in other schools to develop subject-related teaching skills. Supporting this, Japanese teachers reported higher needs of both diversity and subjects than teachers in the other countries. Additionally, the school sizes in Japan can explain stronger influences of principal instructional leadership than Singapore and Korea because principals in small schools tend to have direct influence on teachers (Clarke and Wildy 2004; Mohr 2000). Similarly, the largest school size of Singapore may encourage principals to utilize more indirect approaches, relying on teacher leaders to promote PD participation.

Notably, for factors excluding principal instructional leadership, public schools showed much higher influence on teacher PD compared to private schools in Japan, but Korea did not show significant difference. This reflects different functions of private schools in these two countries. In Japan, private schools are not under governmental control. In contrast, private school teachers in Korea are under the influence of the Ministry of Education and must meet national standards regarding PD, evaluation, and promotion. Thus, our results suggest that policy makers and educational leaders may think about how to decrease gaps in teacher learning between private and public schools regarding equity for teachers and teaching quality.

We acknowledge a few limitations of this study and want to suggest future research to continue to address these issues. First, our findings do not reveal any causal relationships and do provide relational information. Additionally, we did not examine whether teachers’ participation in PD is directly linked to its outcomes such as improving instructional practices and/or student achievement. Thus, future studies may extend our findings by connecting teachers’ PD participation with changes in instructional practices and student achievement. Second, three survey items for instructional leadership measured in TALIS may not fully capture principal instructional leadership activities, especially in the three countries of this study. For example, instructional leadership measures in TALIS did not include an element regarding creating climates for learning, which has been often examined by instructional leadership literature (e.g., Hallinger and Murphy 1985; Hallinger and Walker 2017; Murphy 1990). Thus, interpretation of the results should be carefully addressed, and readers should not over generalize our findings. Third, there are some possible omitted variable biases. For instance, we did not include information about whether teachers received financial support to participate in PD activities. Fourth, we assumed missing cases as missing completely at random for complete case analyses at each dependent variable using the list-wise deletion method, which can result in reduced sample size and some possible bias in estimates. Results may differ if future research uses a multiple imputation method. Finally, as we noted in the earlier sections, our models did not include factors regarding teacher PD policies due to the limitation of the secondary data. Including these variables can show different results in terms of principal leadership influence on teachers’ participation in PD in these countries. We suggest that linking the schools in the TALIS data to other national datasets that inform PD-related policies would be useful for future study. In addition, researchers can analyze teacher training systems and related policies in these three countries using document analysis or comparative case study method to extend our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that the influence of principal instructional leadership on teachers’ participation in PD varies across PD types and countries. Among the six forms of PD, the relation between principal instructional leadership and PD6 (mentoring, peer observation, and coaching) is stronger compared to other types of learning in the three countries. This suggests that principals can have more impacts on teacher learning by formally arranging opportunities and resources for teachers’ collaborative learning. Mentoring, peer observation, and coaching activities are regarded as effective forms of PD in that they rely on interactions and co-development of expertise between teachers and focus on teachers’ individual needs to improve instructional practices. In the three countries of which teacher retention is high and career ladders are well-established, principals can relatively easily arrange mentorship, find expertise for coaching, and encourage peer observations in their schools to support teacher learning.

In terms of country-specific characteristics, principal instructional leadership was associated with multiple types of PD (courses/workshops, conferences/seminars, and mentoring/peer observation/coaching) in Japan while Singapore and Korea were not. While the majority of teachers in the three countries participated in PD1 and PD2 types, the influences of instructional leadership were not significant in Singapore and Korea. Considering the government-driven teacher policies in these two countries, teachers’ participation in traditional types of PD may rely more on individual teachers, collective norms within a teaching job, or policy-guided systems than principals’ efforts to lead teacher learning. In addition, if there are divergences between national policies and individual school contexts, principals may prefer certain types of PD for teachers. Principals can discourage teacher participation outside school PD if they do not align with school organizational goals and school focus, as existing research suggested (Lee et al. 2015). However, for the further clarification, more research is needed to explain why Japanese principal leadership showed stronger relations in traditional types of teacher PD compared to other two countries.

Given the findings, we want to address two different perspectives for interpreting principal instructional leadership influence on teacher PD. On one hand, if national and local education authorities establish policy and support systems to promote teacher development, teachers may have equal opportunities and resources to access certain types of PD to some degree, regardless of principal leadership. Thus, within the system, weak relationships between instructional leadership and teachers’ participation in PD may still represent an equal distribution of teachers’ opportunities to participate in PD. Moreover, the structured systems for teacher development suggest instructional leadership in the three countries should be considered with principals’ management skills, such as how they coordinate and utilize policies as resources to support teacher learning. When multiple resources are available from established policies, school leaders’ capacities to organize financial and human resources combined with their efforts to promote teacher learning are important.

On the other hand, from the leadership perspective, having weak relationships between instructional leadership and teacher learning means principals do not have enough space to exert influence on teacher development. In this case, it is worth considering how policies can support principal instructional leadership by providing enough room for principals. In addition, our findings imply that principal leadership development can focus more on instructional leadership skills that support school-based mentoring, peer observation, and coaching for teachers to meet their individual needs and develop expertise collaboratively. Leadership training for principals in these countries need to focus more on skills to support school-based learning in promoting teacher development. Thus, our study has potentially important implications for how policy makers and school leaders can effectively support teacher PD, which in turn helps improving schools.

The growth of international databases on teachers such as TALIS contributed to our understanding of cross-national characteristics of teacher learning (Akiba 2017). Our study builds on and extends this line of research by adding evidence about the relations between principal leadership and teacher PD in the three Asian countries. Combined with regional studies, we reflected contexts of leadership and teacher PD in Japan, Singapore, and South Korea in designing our study and interpreting the results. We also tried to increase robustness in analyses by selecting survey items, models, and weights. We hope that our findings promote critical dialogues between principal leadership and teacher learning in international research and policy for developing teachers.

Notes

We chose these countries for three reasons. First, all three countries have shown relatively high levels of student academic achievement in international assessments, and international researchers have been interested in their teacher education and school systems (e.g., Mourshed et al. 2011; OECD 2014a; Wei et al. 2009). Second, they exhibited marked similarities in terms of teacher education systems (e.g., government initiated) and high levels of teacher participation in professional development compared to other countries. Third, these countries have unique cultural and policy environments that affect teaching and leadership development despite their similarities.

For more information on how we used sampling weights for analyses, see the methods section.

In this study, we use “South Korea” and “Korea” interchangeably.

In South Korea, all public school teachers and principals are required to move to a different school within the city or province every four to 5 years (Han 2018).

TALIS databases, questionnaire materials, and the technical report are available at www.oecd.org/talis.

There are sampling weights at each level. Since we were concerned about the effects of principal instructional leadership on the teachers’ participation in PD, both levels of units were included in one model simultaneously.

Among them, need of PD for diversity and need of PD in subject matter and pedagogy are also continuous latent factor variables provided by the TALIS 2013 dataset, estimated by MGCFA across the countries.

Estimation results without weights were almost similar to those with both level weights. However, estimation results of the same models using only the final teacher weights were very different from the ones using both weights.

We checked goodness of model fit using a Wald test on the full model against the unconditional model, and concluded that all included predictors across countries were statistically significant at .05 level. This indicates that the full models with random intercept estimates are significant and the hypothesis that the effects of teacher and school factors are simultaneously equal to zero can be rejected at .05 level.

Japan had the smallest average school size (499 students), Korea was second smallest (835 students), and Singapore had the largest school size (1269 students).

References

Akiba, M. (2013). Teacher license renewal policy in Japan. In M. Akiba (Ed.), Teacher reforms around the world: Implementations and outcomes (pp. 123–146). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Akiba, M. (2017). Editor’s introduction: Understanding cross-national differences in globalized teacher reforms. Educational Researcher,46(4), 153–168.

Akiba, M., & LeTendre, G. (2009). Improving teacher quality: The US teaching force in global context. New York: Teachers College Press.

Akiba, M., Wang, Z. E., & Liang, G. (2015). Organizational resources for professional development: A statewide longitudinal survey of middle school mathematics teachers. Journal of School Leadership,25(March), 252–285.

Aspfors, J., & Fransson, G. (2015). Research on mentor education for mentors of newly qualified teachers: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Teaching and Teacher Education,48, 75–86.

Babinski, L. M., Amendum, S. J., Knotek, S. E., Sánchez, M., & Malone, P. (2018). Improving young english learners’ language and literacy skills through teacher professional development: A randomized controlled trial. American Educational Research Journal,55(1), 117–143.

Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the best performing school systems come out on top. London, UK: McKinsey & C.

Bautista, A., & Ortega-Ruiz, R. (2015). Teacher professional development: International perspectives and approaches. Retrieved from http://repositorio.ual.es/bitstream/handle/10835/3929/Bautista%20En%20ingles.pdf?sequence=1.

Bjork, C. (2000). Responsibility for improving the quality of teaching in Japanese schools: The role of the principal in professional development efforts. Education and Society,18(3), 21–43.

Burns, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Teaching around the world: What can TALIS tell us. Stanford: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

Butler, D. L., Schnellert, L., & MacNeil, K. (2015). Collaborative inquiry and distributed agency in educational change: A case study of a multi-level community of inquiry. Journal of Educational Change,16(1), 1–26.

Chen, Y., Cheng, J., & Sato, M. (2017). Effects of school principals’ leadership behaviors: A comparison between Taiwan and Japan. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice,17(1), 145–173.

Clarke, S., & Wildy, H. (2004). Context counts: Viewing small school leadership from the inside out. Journal of Educational Administration,42(5), 555–572.

Coburn, C. E. (2001). Collective sensemaking about reading: How teachers mediate reading policy in their professional communities. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,23(2), 145–170.

Collinson, V., Kozina, E., Kate Lin, Y. H., Ling, L., Matheson, I., Newcombe, L., et al. (2009). Professional development for teachers: A world of change. European Journal of Teacher Education,32(1), 3–19.

Craig, C. J. (2017). International teacher attrition: multi-perspective views. Teachers and Teaching,23(8), 859–862.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2005). Teaching as a profession: Lessons in teacher preparation and professional development. The Phi Delta Kappan,87(3), 237–240.

Darling-Hammond, L., Burns, D., Campbell, C., & Hammerness, K. (2017). Empowered educators: How high-performing systems shape teaching quality around the world. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher,38, 181–200.

Desimone, L. M., & Pak, K. (2017). Instructional coaching as high-quality professional development. Theory Into Practice,56(1), 3–12.

Donohoo, J. (2013). Collaborative inquiry for educators: A facilitator’s guide to school improvement. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Fernandez, C. (2002). Learning from Japanese approaches to professional development. Journal of Teacher Education,53(5), 393–405.

Garet, M. S., Porter, C. A., Desimone, L., Birman, F. B., & Yoon, K.-S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal,38(4), 915–945.

Gersten, R., Dimino, J., Jayanthi, M., Kim, J. S., & Santoro, L. E. (2010). Teacher study group: Impact of the professional development model on reading instruction and student outcomes in first grade classrooms. American Educational Research Journal,47(3), 694–739.

Goh, C. T. (1997). Speech by prime minister Goh Chok Tong at the opening of the 7th international conference on thinking, (June 2, 1997). Suntec City Convention Centre Ballroom. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/speeches/1997/020697.htm.

Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching Theory and Practice,8(3), 381–391.

Hairon, S., & Dimmock, C. (2012). Singapore schools and professional learning communities: Teacher professional development and school leadership in an Asian hierarchical system. Educational Review,64(4), 405–424.

Hallinger, P. (1995). Culture and leadership: Developing an international perspective in educational administration. UCEA Review,36(1), 3–7.

Hallinger, P. (2005). Instructional leadership and the school principal: A passing fancy that refuses to fade away. Leadership and Policy in Schools,4(3), 221–239.

Hallinger, P., & Murphy, J. (1985). Assessing the instructional management behavior of principals. The Elementary School Journal,86, 217–247.

Hallinger, P., & Walker, A. (2017). Leading learning in Asia: Emerging empirical insights from five societies. Journal of Educational Administration,55(2), 130–146.

Han, S. W. (2018). School-based teacher hiring and achievement inequality: A comparative perspective. International Journal of Educational Development,61, 81–91.

Hargreaves, A. (2007). Sustainable professional learning communities. In L. Stoll & K. S. Louis (Eds.), Professional learning communities: Divergence, depth and dilemmas (pp. 181–195). New York: Open University Press.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York: Teachers College Press.

Harris, D. N., & Sass, T. R. (2011). Teacher training, teacher quality and student achievement. Journal of Public Economics,95(7), 798–812.

Heck, R. H. (1992). Principals’ instructional leadership and school performance: Implications for policy development. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,14(1), 21–34.

Hiebert, J., & Stigler, J. W. (2017). Teaching versus teachers as a lever for change: Comparing a Japanese and a US perspective on improving instruction. Educational Researcher,46(4), 169–176.

Hill, H. C., Beisiegel, M., & Jacob, R. (2013). Professional development research: Consensus, crossroads, and challenges. Educational Researcher,42(9), 476–487.

Hord, S. M. (1997). Professional learning communities: Communities of continuous inquiry and improvement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Horn, I. S., & Little, J. W. (2017). Attending to problems of practice: Routines and resources for professional learning in teachers’ workplace interactions. American Educational Research Journal,47(1), 181–217.

Jacob, R., Hill, H., & Corey, D. (2017). The impact of a professional development program on teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching, instruction, and student achievement. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness,10(2), 379–407.

Kim, S., & Kim, E. P. (2005). Profiles of school administrators in South Korea. Educational Management Administration & Leadership,33(3), 289–310.

Lee, M., & Kim, J. (2016). The emerging landscape of school-based professional learning communities in South Korean schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Education,36(2), 266–284.

Lee, S., Lee, J., Heo, S., Park, S., Han, S., & Han, E. (2015). The qualitative meta analysis of attributes in teacher learning community. Korean Journal of Educational Research,53(4), 77–101.

Lewis, C., Perry, R., & Hurd, J. (2004). A deeper look at a Lesson Study. Educational Leadership,61(5), 18–22.

Lewis, C., Perry, R., Hurd, J., & O’Connell, M. P. (2006). Lesson Study comes of age in North America. Phi Delta Kappan,88(4), 273–281.

Louis, K. S., Dretzke, B., & Wahlstrom, K. (2010). How does leadership affect student achievement? Results from a national US survey. School Effectiveness and School Improvement,21(3), 315–336.

Ma, X., & MacMillan, R. B. (1999). Influences of workplace conditions on teachers’ job satisfaction. The Journal of Educational Research,93(1), 39–47.

Marks, H. M., & Louis, K. S. (1997). Does teacher empowerment affect the classroom? The implications of teacher empowerment for instructional practice and student academic performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis,19(3), 245–275.

Marks, H. M., & Printy, S. M. (2003). Principal leadership and school performance: An integration of transformational and instructional leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly,39(3), 370–397.

McLaughlin, M. W., & Talbert, J. E. (2006). Building school-based teacher learning communities: Professional strategies to improve student achievement (Vol. 45). New York: Teachers College Press.

Ministry of Education. (2010). Summary of teacher license renewal system. Tokyo: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2012). The teacher growth model. Singapore: Ministry of Education.

Ministry of Education. (2016). Teacher certification manual in 2016. Korea. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from http://www.moe.go.kr/web/107261/ko/board/view.do?bbsId=342&boardSeq=62229&mode=view.