Abstract

Historically, old southern codes were used to regulate the interactions between black males and white females. We draw parallels between these codes and current sexual harassment laws to examine the perceptions of sexual behavior that crosses racial lines. Specifically, we examine how white and black female targets perceived and reacted to the behavior of males of the same and different race than their own. Our results indicate that white women perceive the behavior committed by a man of another race as more sexually harassing than when a white male commits the behavior. Conversely, black women perceive the behavior committed by black men as more sexually harassing than when a man of a different race engages in the same behavior. Further, a similar pattern emerges for reporting sexual harassment. Implications for research and the management of sexual harassment are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sexual harassment has received a considerable amount of research attention in the past three decades. While our understanding of the underlying causes and consequences of sexual harassment has improved, some issues have yet to receive significant attention. Sexual harassment that crosses racial lines has received limited attention in previous research. This is a critical issue as organizations become more diverse. We examine how white and black female targets perceived and reacted to the behavior of white and black males. To understand how race might affect perceptions of and reactions to sexual harassment, we need to understand the historical context of race and sexual behavior. Historically, old southern codes were used to regulate the interactions between black males and white females. Further, black women were property of white slave owners, so legal restrictions did not bind their interactions. Thus, white men could do as they pleased with their property. We draw parallels between these codes and current sexual harassment policies to examine the perceptions of sexual behavior that crosses racial lines. Our results indicate that both white and black women perceive the behavior of black men as more sexually harassing and more threatening. Further, in general, black and white women are more likely to report black men’s behavior than white men’s. Implications for research and the management of sexual harassment are discussed. The purpose of this paper is to examine the intersection of race and gender on the perceptions of and reactions to sexual harassment within organizations. There is a vast literature that has developed theories of sexual harassment (MacKinnon, 1979; Tangri & Hayes, 1997), defined different categories of sexual harassment (Fitzgerald et al., 1995a, 1995b; O'Donohue, 1997), appraised the importance of the power of men and harassment (MacKinnon, 1979), and examined the development of multidimensional aspects of sexual harassment (Fitzgerald, Gelfand, et al., 1995; Fitzgerald, Hulin, et al., 1995; Gelfand et al., 1995). Although this literature has explored many aspects of the situation that affect the definition, antecedents, perceptions, and consequences of sexual harassment, the literature on the issue of racial effects is still in its infancy. Subsequently, there is a paucity of literature that examines harassment that occurs between individuals of different races. As work organizations are becoming increasingly racially diverse (Abramowitz & Teixeira, 2009; Toossi, 2006, 2016; Toossi & Joyner, 2018), this is a critical limitation in the literature. It is important to note that studying this phenomenon is particularly challenging since more private organizations do not examine perceptions of harassment in their organization as it might create a legal liability as organizations are legally responsible for harassment if they know or should have known if the behavior was occurring. Much of the quantitative research of actual victims and targets comes from government organizations such as the United States Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB) and the Department of Defense (DOD, 1995). After 1995, these organizations no longer continued to collect data on the race of the harasser; thus, the data presented in the current paper are unique. We contribute to the sexual harassment literature by examining the issue of cross-racial sexual harassment.

Central to most theories of sexual harassment is the issue of power (Berdahl, 2007; Farley, 1978; Franke, 1997; Gutek, 1985; MacKinnon, 1979; Rospenda et al., 1998; Schein, 1994; Schultz, 1998). One theory is that harassment occurs as an expression of male dominance to keep women out of economically advantageous positions in organizations (Maass et al., 2003; Schultz, 1998) or to protect or enhance sex-based social status at work (Berdahl, 2007; Berdahl et al., 2018). An underlying assumption of this body of research is that males have hold power over women. While this is undoubtedly true for white men and white women, it is not valid for men and women of color and other protected minority categories. We draw on the concept of intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991) and multidimensional masculinities theory (Cooper, 2010; Cooper & McGinley, 2012). Intersectionality posits that “structures of power interact to produce disparate conditions of social inequality that affect groups and individuals differently” (Cho, 2013). Further, multidimensional masculinities theory posits that “categories of identity are (1) always intertwined with one another and (2) experienced and interpreted differently in different contexts” (Cooper & McGinley, 2012, p. 2). In the case of sexual harassment, we cannot limit our consideration of the phenomena to a single categorical dimension (e.g., gender). Restricting analysis to a single-axis category can marginalize those individuals who are not members of the privileged class (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991). Further, it can obscure our understanding of the motives behind particular behaviors, perceptions, reactions to, and consequences for engaging in such actions. For example, the reactions to a white male repeatedly asking a co-worker for a date may differ from those of a black male engaging in the same exact behavior. In addition, the perceptions of and reactions to the harassment may not only depend on the harasser’s race but also the race of the target.

Both legal scholars (e.g., Benedet, 1995) and organizational researchers (e.g., Chamberlain et al., 2008) have argued that the organization’s context and the relationship between the individuals shape whether specific instances of behaviors are labeled sexual harassment. This occurs because central to the definition of sexual harassment is the designation that the behavior is “unwelcome.” Given that different racial groups have different histories and cultural norms, it seems likely that there is a higher probability of cross-racial sexual behavior being defined as “unwelcomed” and subsequently perceived as harassment. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on the relations between black/white targets and harassers of the same and different races. Specifically, we use a lens of the historical regulation of sexualized behaviors between white and black men and women to understand how current cross-racial sexualized behavior in the workplace might be perceived. We also examine the impact of race on the filing of sexual harassment complaints and targets’ satisfaction with the complaint process. Managing the shifting context for sexual harassment among the races is a particular problem for organizations as they become less male and less white (Abramowitz & Teixeira, 2009; Toossi, 2006, 2016; Toossi & Joyner, 2018) and incidents of sexual harassment that span racial boundaries increase. Therefore, understanding the effect of race on perceptions of harassment becomes a critical issue. Policies and procedures directed at managing sexual harassment among individuals of the same race might need to be modified or assessed in the context of cross-race sexual harassment.

The current paper examines these perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment that cut across racial lines focusing on incidents of cross-racial harassment in the military. The first part of the paper presents our theoretical framework that grounds the study of sexual harassment in the literature on intersectionality and multidimensional masculinity theory (MMT). The second part relates present issues of sexual harassment to old southern codes that regulated the relationship between white women and black men in society. We then present our analyses and policy recommendations for organizations.

Background

Sexual Harassment

Defining sexual harassment presents a formidable challenge to researchers and practitioners because it is both a behavioral phenomenon and a legal construct. Behaviorally, harassment has been defined as “unwanted sex-related behavior at work that is appraised by the recipient[s] as offensive, exceeding her [their] resources, or threatening her [their] resources or threatening her [their] well-being” (Fitzgerald et al., 1997, p. 15). Legally, harassment is defined by the context of the specific behavior, including whether it was unwelcome. That is, would a reasonable person find a particular situation (either a single incident or series of events) rising to a level of severe and/or pervasive sexual harassment? Thus, the same behaviors that would be considered sexual harassment in one situation when it is unwelcomed might not be regarded as sexual harassment in another situation. The changing sex roles further complicate this for women, men, and the changing demographics in the American workplace. Consequently, the definition of harassment is somewhat fluid and subject to the shifting social mores.

Predominant theories of sexual harassment suggest that power is an integral component in understanding the causes of sexual harassment in organizations (Cleveland & Kerst, 1993; MacKinnon, 1979; Tangri & Hayes, 1997; Terpstra & Baker, 1988; Wilson & Thompson, 2001). Researchers suggest that power can be conferred based upon individual characteristics, the organizational structure, or society at large (Cleveland & Kerst, 1993; Wilson & Thompson, 2001). Although they recognize that other factors can contribute to the causes of sexual harassment, power plays a central role. These sources of power map on to several theories of sexual harassment, such as the organizational model (Terpstra & Baker, 1988) and the sociocultural model (Tangri et al., 1982).

These models posit that sexual harassment occurs because of the power (either formal or informal) that specific individuals have over others in the particular context (Terpstra & Baker, 1988). The sociocultural model, which partly subsumes the organizational model, suggests that sexual harassment serves to “manage ongoing male–female interactions according to accepted sex status norms, and to maintain male dominance occupationally and therefore economically, by intimidating, discouraging, or precipitating the removal of women from work.” (Tangri et al., 1982, p. 40). This paper focuses on the sociocultural model as it reflects the reinforcement of the power structure that provides men with higher status than women in the broader social context (Mackinnon, 1979). This is particularly important because most sexual harassment in organizations is male to female harassment and occurs among peers at the same organizational level (Bostock & Daley, 2007; Gettman & Gelfand, 2007). This suggests that the power used is informal, based upon the social status of men and women. Research has supported both models (see McDonald, 2012 for a review). It explains why there is a higher prevalence of male to female harassment than female to male harassment even when women possess more power (Lampman et al., 2009).

Race represents another form of social power that has deep roots in the broader society and the workplace (Lucas & Baxter, 2012). This power dynamic is one reason why the issue of race is a critical factor affecting perceptions of and reactions to sexual harassment. Indeed, sexual harassment scholars (O’Donohue, 1997) recognize that this form of social power affects how sexual harassment that crosses racial lines might affect perceptions of and reactions to incidents. When race is introduced as a factor, there may be a reversal of social power between white women and black men. Historically, in broader society, white women had the power to punish black men who treated them in ways that they perceived as inappropriate. Scholarship examining the relationship between black men and white women can be traced to the attempt by scholars to explain racial violence that had consequences for members of the black male population, such as lynching. As noted by Dora Apel in Imagery of Lynching: Black Men, White Women, and the Mob (2004), racial violence was rooted in race and gender anxieties that criminalized sexual relations between black men and white women. This work links the lynching of black men to the violation of social customs related to white females. It showed the power of white females when they charged a black man with what can be viewed as the original sexual misconduct in society.

Goff and Kahn (2013) highlight that one of the problems of social psychology in studying phenomena such as harassment is that it tends to focus on single constructs such as race or gender and tends to ignore that “race and gender mutually construct each other” (p. 365). Consequently, they suggest that “many definitions of gender discrimination are to some degree racist” (p. 365). Two theoretical lenses that might help us understand the phenomenon of cross-racial sexual harassment are intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) and multidimensional masculinities theory (McGinley & Cooper, 2012). The concept of intersectionality was introduced in the late 1980s (Crenshaw, 1989, 1991) to highlight the fact that social phenomenon such as harassment could not be reduced to a single axis, such as gender, because white women’s experiences of sexual harassment were qualitatively different from those of black women. Accordingly, Crenshaw (1989) argues that by focusing attention on the most privileged group (in the case of harassment, white women), the analyses of racism and sexism become distorted. More generally, intersectionality suggests that characteristics such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and so on need to be considered in tandem rather than focusing on individual attributes (Cho et al., 2013). Thus, to fully understand sexual harassment that crosses racial lines, we need to examine how the perception of members who belong to the privileged class (white women) might differ from other racial groups.

In addition, we also need to consider how the race of the harasser might affect these perceptions. While models of harassment often focus on the social power that men have over women, there is an assumption that all men have equal power. Multidimensional Masculinities Theory (MMT) posits that the effects of multiple identities and masculinity are intertwined such that the power granted to men based upon cultural norms and legal mechanisms may not be given to all men equally (McGinley & Cooper, 2012). Race is an essential factor for determining power that men may be able to exercise. According to Dowd et al. (2012), “Race is perhaps the most powerful determinant of place in the hierarchy, in addition to sexual orientation and class. Race may nearly completely obliterate gender advantage, so some men, in reality, do not exercise dominance in many, if any, contexts” (p. 28). Further, they posit that “masculine privilege is neither absolute nor universal” (p. 30). This suggests that black men’s behavior may be perceived as more offensive since they do not possess the same social power bestowed upon white men. Consequently, targets may perceive specific incidents as harassment simply because the perpetrator was black.

Within the context of work organizations, Thomas (1989, 1993) examines how race affects the relationship development within organizations between white and black employees. He suggests that the interaction between race and gender is essential in understanding how these relationships develop. In his qualitative study of mentoring relationships, he found that race even affected the degree to which individuals were willing to spend time with members of the opposite sex of a different race (Thomas, 1989). One white female employee was told, “You’re hanging around with this black man too much, it will damage your career,” (Thomas, 1989, p. 283). A black male employee expressed his avoidance of white women, “I don’t want to be seen too often talking with white females, … there is a lot of history that says that black men being somewhat familiar with white women isn’t healthy” (Thomas, 1989, p. 283). He suggests that the social psychology of slavery and the post-slavery expressions of racial animosity often shape how racial dynamics affect interpersonal relationships (Thomas, 1989). Combined with the findings of Guiffre and Williams (1994), who examine the relations between white and Hispanic employees, race appears to affect how interpersonal interactions are perceived and labeled. Because of their qualitative nature, these studies have small sample sizes, and consequently, the findings may not generalize to other situations.

Research has begun to examine the issue of race for the phenomena of sexual harassment. A good deal of this research has compared the frequency of black women to white women experiencing sexual harassment (Berdahl & Moore, 2006; Bergman & Henning, 2008; Buchanan et al., 2008; Firestone & Harris, 2003; Kalof et al., 2001; Kohlman, 2010; Texeira, 2002; Welsh et al., 2006). Although the research on the frequency of cross-racial harassment is an important contribution to the literature, some of this research assumes that sexual harassment which crosses racial lines has the same meaning as instances that do not. It does not elucidate the perceptions of and responses to cross-racial harassment. Given that the definition of sexual roles in society are based not only on gender but are also influenced by race, we believe that there is more work to be done in this area.

Several studies have examined the effects of race on perceptions of sexual harassment (Buchanan & Omerod, 2002; Shelton & Chavous, 1999; Wuensch et al., 2002). These studies have produced somewhat mixed results. Shelton and Chavous (1999) found that white women perceive the same situations as more harassing than black women, while Buchanan and Omerod (2002) found the opposite effect; Wuensch et al. (2002) find no differences. One reason cited by this research is that the concept of sexual harassment for black women is inextricably linked to race. Thus, the phenomenological experience is different for white and black women (Buchanan & Omerod, 2002; Wuensch et al., 2002). A second reason speculated for these inconsistent results is that the race of the harasser was not considered. Only a handful of studies have examined sexual harassment between people of different races (Shelton & Chavous, 1999; Sydell & Nelson, 1998; Wuensch et al., 2002). This research found that harassment of white women by black men is perceived as being worse than white women being harassed by white men. Wuensch et al. (2002) found that perceptions of harassment for black women did not change depending on the harasser’s race. One limitation of these studies is that they are based upon participants’ reactions to vignettes describing harassers and targets of different races. Although vignettes are a valuable tool for studying phenomena, they are problematic when the participants are unable to place themselves in the experiences described in the vignettes (Lind & Tyler, 1988). Participants whose race is different from the target in the scenario might not truly understand the racial context of behavior steeped in a unique history of race and its influence on sex roles, differential treatment, and experience. To fill this gap in the literature, we examine the perceptions and reactions of actual targets of cross-racial harassment. To understand how race might influence perceptions of sexual harassment, we now turn to a brief discussion of race and sexual behavior in broader society.

Race, Sexuality, and Old Southern Codes

Although laws governing sexual harassment and guidelines for the workplace have existed for approximately 30 years, customs and laws regulating sexual behavior between races in broader society have existed for centuries. Though not legally codified until the 1800s, customary practices regarding the treatment of black men and women developed after the first slave ship arrived in Virginia in 1619 (Stephenson, 1906). These customs earned legal status in the South in the 1800s, as behavior between black men and white women was regulated. These laws and customs were dependent on accusations of white females, which created consequences for black males and entire black communities. We juxtapose the complaints against black men by white females during this period against women’s complaints today and consider the consequences for these men. When dealing with cross-racial sexual harassment issues, can policies and practices become, simply put, old southern codes in new legal bottles?

In addition to minorities’ current lack of social status in the workplace, perceptions of and reactions to cross-racial harassment might also be influenced by the historical context of black/white socio-sexual relations. Specifically, starting in the eighteenth century, early colonial society developed codes and laws that regulated the behavior of slaves; these codes became increasingly more stringent over the following century and specified the relationship between black men and white women. These early laws bear an interesting resemblance to sexual harassment policies in the workplace today. Not only did these codes regulate behavior, but they also removed intent as a condition of determining a behavior’s deviance. Under these codes, a black man could be lynched for an “unwarranted” glance at a white woman (Newkirk, 2009).

Similarly, sexual harassment guidelines define the deviance of the behavior based upon the target’s reactions and not the intent of the harasser. Sexual harassment policies in organizations bear some similarities to laws that monitored the relationship between white women and black men. They have been transferred to the workplace and apply to all men. Although current sexual harassment guidelines should apply to all men equally, the behavior of black men and white men might not be perceived or responded to in the same way due to this historical context. This may serve to discriminate and punish black men such that it maintains the social hierarchy in which black men are kept in a lower position than white men.

In an in-depth study of boundary lines and the labeling of sexual harassment in the workplace today, Giuffre and Williams (1994) presented one of the first indications of old southern codes in new legal bottles. They noted that white women identified the sexual advances of minority men as sexual harassment, but not the identical behaviors of their white male co-workers. White women drew boundaries lines differently for white men, and consequently, were willing participants in heterosexual activities only in racially homogenous contexts. They concluded that white women could not conceive of having a legitimate relationship with the minority men because of cultural and racist attitudes. However, “the white men, on the other hand, can hug, kiss, and pinch rears of the white women because they have a mutual understanding—implying reciprocity and the possibility of intimacy” (Giuffre & Williams, 1994, p. 390).

We believe that this historical context of regulating interracial relationships in society will likely affect the current perceptions of sexual harassment in the workplace that crosses racial boundaries. Even though the laws regulating behavior between black men and white women no longer exist, the societal beliefs that produced these codes still linger; these subtle effects lead white women to perceive the behavior of black men to be more harassing than when white men engage in the same behavior. Some support for this historical effect might be seen in the perception of interracial marriage. Although attitudes toward interracial marriage, in general, have improved since the 1960s, black/white marriage is still perceived more negatively than other forms of interracial marriage (Golebiowska, 2007). Djamba and Kimuna (2014) highlighted racial differences in the perception of black/white marriages; while 53.7% of black respondents in the General Social Survey approved of a close relative marrying a white person, only 26.3% of white respondents approved of a close relative marrying a black person. Further, Torche and Rich (2017) found that the proportion of black/white relationships between black men and white women declined between 1980 and 2010. Taken together, these results suggest that there is still a stigma associated with the relationship between black men and white women.

Similarly, the perception of white men’s harassing behavior toward black women might also be affected by the history of relationships between white men and black women. Although there were no laws regulating the sexual behavior between white men and black women until the emancipation of slaves, black women who were enslaved were property that could be used by white men in any manner they desired (Williams, 1991). Black women had little control over their own bodies and were subject to the whims of their white slave masters. This lack of explicit support for black women and the willingness to turn a blind eye to the violence committed against them led many black women to believe that they had no control, even over their own bodies (Morton, 1991).

Even after slavery was abolished, black women faced challenges to gain control over white men for control of their own bodies. After the Civil War, there was a movement to reform rape laws to offer more protections to females, in general. Legislators who were predominantly white and male sought to exclude legal protections for black females in cases of sexual assault and rape (Dunlap, 1999). African American Activist Frances Joseph-Gaudet criticized these legislators for criminalizing interracial marriage but not interracial sex (Dunlap, 1999). Further, she suggested that the laws preventing interracial marriage and legislators’ insistence that black females be excluded from protection under rape reform were aimed at preventing black men from having sex with white women but allowed white men to continue their sexual proclivities with black females (Dunlap, 1999). Under reforms, white men’s criminal sexual behavior toward white women was punished, but the same behavior committed with black women was not. Thus, white men’s deviant sexual behavior toward black women was not only an expression of male dominance over women, but it was also a racist expression of white supremacy. Thus, as Omerod and Buchanan (2002) suggest, black women may perceive the harassment by white men as more of an expression of racist behavior rather than sexist behavior. Consequently, white men’s behavior may have been seen as an expression of racism, while black males' similar behaviors were more likely to be perceived as sexist. Thus, the perception of white men’s sexually harassing behavior of black women might be perceived as less as sexual harassment than that of black men’s behavior and more of an offense of racism because it resonates with a particular historic behavior toward black women. Black women may still consider the sexualized behavior of white men offensive, disturbing and threatening; it is just not labeled as sexual harassment.

Hypothesis 1

Black men’s sexualized behavior will more likely be perceived as sexual harassment than white men’s behavior.

Hypothesis 2

Behavior that occurs between individuals of different races will be perceived as more offensive, disturbing and threatening than behavior that occurs between individuals of the same race.

Although an extensive analysis of the literature on the protection of white females through codes, laws and customs, is beyond the scope of this paper, we are interested in how the punishment of such crimes historically might relate to penalties for the violation of sexual harassment policies and regulations. In the old south, black men accused of sexual impropriety were seen as having violated either a criminal statute or some norm of the racial caste code and were often punished with physical harm or violence. Tolnay and Beck (1995) found that the violation of some sexual norm, e.g., rape, incest, miscegenation, or improper conduct with a white woman, accounted for 33.6 percent of the reasons given for mob violence. This historical context of the violence advocated for the punishment of cross-racial harassment might extend to the workplace today in that incidents of sexual harassment that cross-racial lines, especially those that occur between black harassers and white targets, might be perceived as “worse” than harassment that occurs within one’s own race and consequently require more severe punishment.

One of the reasons the examination of actual cross-racial sexual harassment has received little attention in the literature is the traditional lack of diversity in organizations, especially in supervisory positions. Our military dataset allows us to explore race and sexual harassment. Indeed, the military is the only organization in America where black men supervise white females to a significant degree. It is also an organization that has produced high-profile sexual harassment cases that involve different races and people of the same race.

Scholarly research on sexual harassment within the military, as well as official reports, demonstrate that the patterns of behavior in the armed forces are similar to those found in other organizations (Bastian et al., 1995; Chema, 1993; Firestone & Harris, 1994; Harris & Firestone, 1996; Miller, 1997; Munson et al., 2001; Zimmerman, 1995). Large percentages of military women (77%) reported that they had experienced sexual harassment of some form (Munson et al., 2001). Most of the harassment occurring in the military is in the form of hostile work environment (Bastian et al., 1995; Lipari & Lancaster, 2002), while relatively few individuals experience sexual coercion.

The military has experienced several high-profile sexual harassment cases. The event that brought race to the center of the discussion in 1996 took place at the Army’s Aberdeen Proving Grounds training facility. This training center was the site of massive charges of sexual harassment. Indeed, the National Organization of Women (NOW) asked all military branches to take immediate action. The Army responded by providing 800 numbers so that women could report sexual misconduct. The Department of Defense authorized investigations of all Army military training centers. NOW demanded that the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard install 800 numbers. Former President of NOW, Karen Johnson, noted that "Aberdeen is only the most blatant and severe example of the denigration and discrimination women face every day—both in the military and in workplaces across the country. The military can lead the way in changing the culture of misogyny that allows and encourages men to harass and assault women and girls on the job, in the streets and classrooms” (National Organization of Women, 1996).

As information emerged on sexual misconduct at Aberdeen, race entered the picture, notably as reported in the media (National Organization of Women, 1996):

“… all 13 men facing charges in the scandal at Aberdeen Proving Ground are black, while the great majority of their accusers are white women. And they contend that black men also have been disproportionately accused in the Army cases pending elsewhere around the United States…” (Richter, 1997)

“…This raises the old images of black men and white women that we just don't need in this day and age,” said Janice E. Grant, of the Harford County, Md., NAACP, who has called for a civilian probe into the matter.

"The numbers here just don't add up." (Richter, 1997)

“Leroy Warren Jr., an NAACP national board member said the group "isn't in the business of protecting people who have committed crimes." But he said the authorities "aren't getting the white guys. There's a dual system of justice at the Pentagon and in this country." (Richter, 1997)

The quotes above illustrate how accusations and charges of sexual harassment are made along racial lines that mimic sexual relations of the old south. White women will be more likely to report the inappropriate behavior of black men compared to white men. Similarly, as discussed earlier black women may not perceive white men’s sexualized behavior as sexual harassment and therefore are less likely to report it as such. Black women may be more likely to perceive black men’s inappropriate behavior as sexual harassment because the racist element is not present, and consequently, are more likely to report it. Stated formally:

Hypothesis 3

Black men’s sexualized behavior is more likely to be reported as sexual harassment than white men’s behavior.

One of the challenges of reporting processes is that they are often not utilized. Research indicates that only 2 to 20% (depending on the study) of individuals who experience sexual harassment file a formal complaint (see Cortina & Berdahl, 2008 for a review). One reason why individuals do not report harassment is that they do not believe it will result in a good outcome. Indeed, several studies indicate that 33 to 57% of targets who report sexual harassment were not satisfied with the outcome of the process (Bingham & Scherer, 1993, Gruber & Smith, 1995; Gutek & Koss, 1993; Martindale, 1990; Morral et al., 2015; USMSPB, 1995). This may be particularly true for sexual harassment instances that cross-racial lines. The target’s reaction to the outcome of the complaint process might be affected by the race of the harasser. As previously discussed, instances of cross-racial harassment may be perceived as more offensive than when a member of one’s race commits the behavior. Consequently, targets may expect punishments to be more severe as the level of perceived offense is higher, and that punishment should reflect this. Given the limits on the penalties that can be given in organizations (violence and lynching are not viable options), individuals who experience harassment that crosses racial lines may be less satisfied with the outcome of such complaints because they believe that the punishment doled out by organizations is not severe enough to deal with a highly offensive situation.

Hypothesis 4

Individuals who report behavior committed by someone of a different race are less likely to be satisfied with the outcome of a complaint than when the behavior occurs between individuals of the same race.

Methods

Data

We used the Status of the Armed Forces Survey: 1995 Form B-Gender Issues, which the United States Department of Defense administered in 1995 (Bastian et al., 1995). The survey was used to examine sexual harassment and other related issues. The random sample of 50,394 military personnel who were sent the Form B survey was non-proportionally stratified. 28,296 service members returned usable surveys, resulting in a response rate of approximately 56%.

We focused our analyses on female soldiers who were harassed by males. There were both statistical and theoretical justifications for this decision. Although women are not the only targets, they face sexual harassment much more frequently than men (DiTomaso et al., 1989; Terpstra & Baker, 1988; US Merit Systems Protection Board, 1981). Researchers examining this particular dataset have found that men’s and women's experiences regarding sexual harassment are different (Donovan & Drasgow, 1999; Magley et al., 1999) and that same-sex harassment is different from that experienced between the sexes (DuBois et al., 1998). Further, women were sampled approximately four times more than men; combined with men’s low response rate, we did not have a large enough sample size to examine other forms of harassment that crossed racial lines. We further limit our analyses to black and white women. There are two reasons for this restriction. First, the survey provided limited information about race. For example, several racial groups, such as American Indian, Asian, and Pacific Islander, were grouped together. Consequently, we could not assess the effects for certain racial groups. Second, response rates of different racial groups left us with insufficient cases to perform analyses. The racial composition of the usable returned surveys was white, non-Hispanic (62.7%), black (24.0%), Hispanic (3.7%), and Asian/Pacific Islander/American Indian/Eskimo (5.1%) with 4.5% missing data.

This survey was created to assess perceptions and frequency of sexually harassing behavior in the military. In addition, the survey asked participants to recall a specific (critical) incident: “Think about the situation(s) you have experienced during the past 12 months that involved unwanted sex/gender-related attention. Now pick the SITUATION THAT HAD THE GREATEST EFFECT ON YOU.” The survey then prompted respondents to answer specific questions about the incident. To assess the effects of race on perceptions of and responses to harassment, we focused on these critical incidents since the general questions of perceptions and frequency did not contain race information. Thus, our working dataset was limited to those respondents who indicated a critical incident and answered the questions about the incident. Our working dataset contains 5313 women.

Variables

Race

To conduct our analyses, we needed to identify the race of the target and that of the harasser. For the target’s race, participants responded to the question, “What race do you consider yourself to be?” (white, black, or African American; Indian (Amer.), Eskimo, or Aleut; Asian or Pacific Islander; Other race (Please specify)). These data were matched to control data used when administering the surveys. To assess the race of the harasser, participants responded to the question, “Was the racial/ethnic background of the person(s)?” (The same as your own; Different from your own; Some were the same, and some were different; Don’t know). We selected individuals who responded, “the same as your own” or “different from your own.” Note that we cannot determine the exact race of harassers who differed from the targets because of the question's wording. Still, given the racial composition of respondents, it is likely that the majority of cross-racial harassment occurred between black and white individuals. We will address this issue further in the discussion section.

Harassment Type

The sexual harassment literature has revealed three distinct subtypes of harassment behavior (Fitzgerald et al., 1999; Fitzgerald, Gelfand, et al., 1995; Fitzgerald, Hulin, et al., 1995; Gelfand et al., 1995): unwanted sexual attention, coercive sexual behavior, and gender harassment (Fitzgerald, Gelfand, et al., 1995; Fitzgerald, Hulin, et al., 1995). Unwanted sexual attention includes comments or behaviors of a sexual nature that the target considers inappropriate. Coercive sexual behavior is defined as one organization member’s promise, threat, or use of a punishment or reward to compel another organizational member to submit to a request of a sexual nature. Finally, gender harassment includes comments or behaviors designed to belittle or intimidate women. Gender harassment is further broken down into two subcategories of crude/offensive behavior, typically directed toward a specific woman and sexist behavior, which is targeted at women in general. We constructed variables corresponding to these different types of sexual harassment from twenty-two items asking respondents about unwanted, sex-related workplace experiences. These scales are identified as follows: crude/offensive behaviors, sexist behavior, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. These four scales had Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of 0.91, 0.83, 0.86, and 0.95, respectively. We classified individuals’ experiences as falling into one of these four categories. Note that the survey allowed individuals to select multiple behaviors that occurred as part of the situation that had the most significant effect on them. 97% of the individuals indicated three behaviors or less occurred as part of their critical incident, with 50% indicating only one event. We limited our working dataset to those individuals for which all behaviors fell within the same category. The number of incidents by race for each category appears in Table 1. Because there are so few instances of sexual coercion (n = 96) and statistical results might be skewed, we have chosen to focus on the first three categories of behaviors (crude/offensive behaviors, sexist behavior, and unwanted sexual attention).

Perception of Harassment

Participants responded to one question assessing whether they perceived the incident to be sexual harassment, “Do you consider this situation to have been sexual harassment?” using a five-point Likert scale (0 = definitely was not sexual harassment; 4 = definitely was sexual harassment).

Reactions to Harassment

Participants responded to three questions assessing their reactions to the incident, “Was it offensive; Was it disturbing; Was it threatening.” All items were measured using a five-point Likert Scale (0 = not at all; 4 = extremely).

Reporting of Sexual Harassment

Participants responded to one question assessing whether they reported the situation, “Did you REPORT this unwanted sex-related attention to any of the following individuals or organizations; and if so, did it make things better or worse for you?” Respondents were then provided with a list of officials or organizations from the immediate supervisor to Congress to whom they could have reported the incident. If respondents selected any of the individuals on the list, we coded the reporting variable as 1, indicating that they had officially reported the situation; if they made no official complaint, we coded the reporting variable as 0.

Satisfaction with Complaint Outcome

Participants responded to one question assessing their satisfaction with outcomes, “How satisfied are you with the outcome of your complaint?” using a five-point Likert scale (1 = very dissatisfied; 5 = very satisfied).

Results

Perceptions of Sexual Harassment

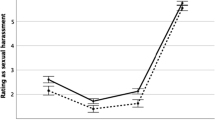

To test whether the race of the target and the race of the harasser affected the perceptions of sexual harassment, we conducted a 2 (target race: black vs. white) × 2 (race of harasser: same vs. different from the target) × 3(big situation: sexist behavior vs. crude/offensive behavior vs. unwanted sexual attention) ANOVA on the perceptions of sexual harassment variable. Results indicated a significant main effect for the harassment type (F2,4999 = 10.15, p < 0.01). Sexist behavior (M = 2.13, SD = 0.04) was perceived as less harassing than crude/offensive behavior (M = 2.35, SD = 0.05) vs. unwanted sexual attention (M = 2.36, SD = 0.05). There were also significant interactions between the target race and the race of the harasser (F1,4999 = 58.52, p < 0.01) and the race of the harasser and the harassment type (F1,4999 = 3,72, p < 0.05). The means are displayed in Table 2. The results demonstrate that across all forms of behavior, black targets perceive the behavior as more harassing when the harasser is of the same race (black). In contrast, white targets perceive the behavior as more harassing when the harasser is of a different race (non-white). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported for white targets but not for black targets.

Reactions to Sexual Harassment

To test whether the race of the target and the race of the harasser had an effect on the three reactions to sexual harassment, we conducted a 2 (target race: black vs. white) × 2 (race of harasser: same vs. different from the target) × 3(big situation: sexist behavior vs. crude/offensive behavior vs. unwanted sexual attention) MANOVA on the three reactions to sexual harassment items. We chose not to scale these items even though the reliability of the items was strong (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81) because we believe that they are conceptually distinct responses. To control for intercorrelations, we conducted a MANOVA rather than three separate ANOVAs. Results indicated a significant main effect for the harassment type (F3,4854 = 16.54, p < 0.01), target race (F3,4854 = 4.91, p < 0.01), and race of the harasser (F3,4854 = 3.84, p < 0.01). These main effects are qualified by a significant interaction between the target race and the race of the harasser (F3,4854 = 4.01, p < 0.01). Univariate results indicated that the interaction was significant for the “was it threatening” item (F1,4856 = 11.94, p < 0.01), and was marginally significant for the “was it offensive” (F1,4856 = 3.16, p < 0.10) and “was it disturbing” (F1,4856 = 3.53, p < 0.10) items. Means for these items are shown in Table 3. In general, black targets’ reactions did not differ depending on the race of the harasser. In contrast, white targets reacted more negatively when the harasser was of a different race (non-white). Hypothesis 2 was supported for white targets but not for black targets.

We now turn to the relationship between race and the filing of a sexual harassment complaint. We conducted a stepwise logistic regression on the “I filed a formal complaint” response. In the first step, we entered the main effects, in the second step, we entered the two-way interaction effects, and in the third step, we entered the three-way interactions. We created two dummy variables for the harassment type variable. The first step in the equation was significant.

Χ2 (4, N = 5020) = 33.98, p < 0.01. In this equation, both harassment type dummy variables were significant, β = 0.61 (p < 0.05) and β = 0.45 (p < 0.01) as was the race of the harasser β = 0.46 (p < 0.01). Sexist behavior was less likely to be reported than crude/offensive behavior or unwanted sexual attention. In addition, harassers whose race was different from their targets were more likely to be reported. The second step in the equation was also significant Χ2 (5, N = 5020) = 16.45, p < 0.01. In this equation, the only significant interaction was the target race × race of the harasser, β = − 0.99 (p < 0.01). White targets were more likely to report targets whose race differed from their own (non-white), while black targets were less likely to report targets whose race differed from their own (non-black). The third step in the equation was not significant. These results are presented in Table 4. Thus, hypothesis 3 was fully supported.

Finally, we are interested in how satisfied women who filed a complaint were with the complaint process. To test whether the race of the target and the race of the harasser had an effect on satisfaction with the complaint outcome, we conducted a 2 (target race: black vs. white) × 2 (race of harasser: same vs. different from the target) × 3 (big situation: sexist behavior vs. crude/offensive behavior vs. unwanted sexual attention) ANOVA on the item “how satisfied are you with the complaint process overall” item. Results indicated a significant main effect for the harassment type (F2,1519 = 5.69, p < 0.01). Individuals who reported sexist behavior (M = 2.85, SE = 0.05) were less satisfied with the complaint process than those who reported crude/offensive behavior (M = 3.17, SE = 0.09) or unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.07, SE = 0.09). There was also a significant interaction between the target race and the race of the harasser (F1,1519 = 5.04, p < 0.05). The means are displayed in Table 5. White women were more satisfied with the complaint process when the harasser was the same race (white). There is no difference in satisfaction in the complaint process for black women regardless of the harasser’s race. Thus, hypothesis 4 was supported for white targets but not for black targets.

Discussion

The results of our analyses suggest that there is a robust interaction effect between the race of the harasser and the race of the target. The perceptions of harassment, reactions to harassment, and responses to harassment are different for white females and black females depending on the race of the harasser. White females perceive the behavior of men of a different race compared to the behavior of white men as being more harassing, are more likely to have adverse psychological reactions, and are more likely to report them. Conversely, black females perceive the behavior of black men compared to men of a different race as being more harassing, are more likely to have adverse psychological reactions, and are more likely to report them. In addition, white women are more satisfied with the complaint process when the harassers are white versus black; the race of the harasser does not affect black women’s satisfaction with the complaint process.

For white women, this dovetails with Giuffre and Williams’ qualitative work (1994), which demonstrated that race of the harasser was important in terms of how white females perceive behavior. They argued that it is more difficult for white women to perceive a future with a person of another race. In terms of sexual harassment, this might influence the degree of unwelcomeness. In addition, there might be some fear of black men as savages (Hodes, 1999) that is a residual from old southern lore designed to discourage white women from having contact with black men. These results might, in part, demonstrate the idea that racism in America has changed from the overt fear of and hostility toward black men to a more subtle reaction to their behavior.

Black women were less likely to view the behavior of harassers of a different race as problematic than black men's actions. Although this conflicts with some prior research (Shelton & Chavous, 1999; Wuensch et al., 2002), this could be due to methodological differences. Previous studies have used scenarios that ask the participant how the character in a scenario would feel. Responses might reflect, to some degree, the social desirability of aligning with one’s own race. However, actual targets of harassment might act differently, especially when it comes to the emotionally charged issue of race. As suggested earlier in the paper, black women might be less likely to perceive the inappropriate behavior as sexual harassment when a white man engages in the behavior because they perceive the situation to be more of an issue of racism than sexist behavior. Our results indicated that black women perceived the behavior of men who were of a different race as less sexually harassing than when the harasser was black. However, black women saw the behavior as equally offensive, disturbing and threatening regardless of the race of the harasser. In addition, there may be additional potential reasons that black women perceive the inappropriate behavior of black men more as sexual harassment than when the behavior involves men of another race. First, black women might see the harassment of white men as nothing unusual; that is, they have come to expect it. This follows from the pre-civil rights South, where black women were sexually abused and raped by their white masters/employers and came to see this behavior as part of their lot in life (Morton, 1991). The second reason is that to combat the image of black women as temptresses; they adopted strict moral codes that removed any hint of sexual impropriety (Hine, 1997). Black men were more likely than white men to understand this (as they were trying to overcome their own negative image), and thus sexual harassment by black men might be viewed as more of an affront to this code and black women’s struggles. Finally, and similarly, harassment by black men toward black women might be seen as more of an insult because of their shared struggle to combat racism both in America, in general, and specifically in the military: the harassment might be seen as a betrayal of their common struggle. Future research is needed to determine the underlying mechanism.

Conclusions and Implications for Research and Practice

The purpose of this paper has been to examine the effects of race on the perceptions of and reactions to sexual harassment. We agree with the work of Zuberi (2001), who suggests that interpreting racial statistics requires caution and advises that “…our identities arise from our membership in a distinctive historical, linguistic, religious, and political culture. This group membership leads to our interest in how people are represented and how they represent themselves within a historically specific social context.” (Zuberi, 2001, pp. ix–xx). In the case of our study, it is not that white and non-white men behave differently since we examined the perceptions of the same type of behavior. Instead, it is how the race of the alleged harasser affects how targets make sense of these interactions. Specifically, we contend that the race effects on the perceptions of sexual harassment may very well have their foundation in the old southern codes that regulated the relationship between white females and black males. Further, this racist historical lens manifests and shapes the context of the workplace today. Specifically, this lens may lead individuals to see non-white men’s behavior as more sexually predatory. Consequently, it is still less acceptable for black men to engage in sexualized behavior than white men. Black males often experience the loss of opportunities within the workplace when accused of sexual harassment. Although white males accused of harassment will also experience negative consequences, our results suggest that their behavior is less likely to be perceived as harassment and less likely to be reported. Thus, black males still face subtle discrimination within an organization that they have been integrated into for over 60 years. In the context of the military as an opportunity for black men, it is a bitter irony that they have been able to achieve higher positions of leadership than in most private organizations, yet they are also more likely to have their behavior scrutinized compared to white men.

Another critical issue raised by this study is that research on sexual harassment needs to consider the effect of race on how sexual harassment is defined and how targets respond. As stated earlier, our results deviate from previous research on racial effects on sexual harassment (Shelton & Chavous, 1999; Wuensch et al., 2002). Beyond the possible social desirability biases, another issue is the subtle racism that still exists in the United States. The legacy stereotype of the black male as a sexual aggressor might unconsciously affect the targets’ (even black females) perception and responses to harassment. Accordingly, future research needs to tease out the effect of racism on cross-race harassment. Additional research needs to examine cross-racial harassment between members of other races. Our results suggest that stereotypes and historical contexts of a specific race might influence how the sexual behavior of that race is perceived. In particular, we call on organizations that conduct research on sexual harassment, such as the DOD and USMSPB, to reinstate questions regarding the race of the harasser to help further the understanding of this phenomenon. Further, a more qualitative study of sexual harassment in the military that focuses on cross-race harassment may help us identify factors beyond the historical context that influence targets’ reactions to these events.

The implications of this research must concentrate on how organizations think about sexual harassment policies. The first recommendation is that organizations should include race effects in the training. This training needs to address the issue of how race might affect perceptions of behavior as being harassment and how such situations should be resolved. As diversity within organizations increases, interactions and relationships are likely to occur between individuals of different races. Training needs to inform individuals that in the workplace, women are more likely to perceive socio-sexual behavior as sexual harassment if the person is not a white male. Building this into training could have the effect of saving the opportunity structure for minority males. Harassment complaints should be taken seriously, regardless of the race of the alleged harasser. However, when determining whether harassment occurred, targets should at least consider whether race has played a role in their reaction to the situation.

Along these lines, research on empathy and perspective-taking training has demonstrated some success in reducing racial and gender biases (Lillis & Hayes, 2007; Lueke & Gibson, 2016; Matsuda et al., 2020; Mendoza et al., 2019; Pashak et al., 2018; Todd et al., 2011; Zimmerman & Myers, 2013). Todd et al. (2011) found that non-white participants who were asked to take the perspective of a black target demonstrated less bias. In the area of sexual harassment, Zimmerman and Myers (2013) found that when participants were asked to take the perspective of the female target, sex-based differences in judgments of the harassment were reduced. Some research on perspective-taking suggests that this approach does not always mitigate bias (Epley et al., 2004; Tarrant et al., 2012). The effectiveness of perspective-taking training will depend on the similarity between the individual and the target of the perspective training, how much the individual identifies with the ingroup majority, and the level of bias/prejudice the individual has (Epley et al., 2004; Tarrant et al., 2012; Vorauer et al., 2009). In addition, perspective-taking could increase the cognitive demands and stress on the individual when they take on another individual’s perspective, particularly when that individual is suffering negative consequences (Buffone et al., 2017). A more recent intervention that has shown some success in reducing racial bias combines perspective-taking with mindfulness (Berry et al., 2021; Edwards et al., 2017; Lueke & Gibson, 2015, 2016). This method might help reduce the racial bias that occurs when individuals evaluate situations that might be considered harassment.

Also, the organization should understand that females might not view specific sexually harassing behaviors in the same way when men of different races engage in them. Specifically, women might tolerate a particular behavior when a white male commits the act but not when a non-white male engages in the behavior. A second recommendation is that organizations must encourage reporting of similar behaviors and take similar disciplinary actions for those behaviors regardless of the harasser’s race. By only investigating and punishing the behavior of non-white males, organizations might open themselves up to claims of adverse treatment discrimination. That is, they will be treating non-white males differently than white males and thus be engaged in illegal discrimination. Besides complaint procedures, training can also provide information to potential targets of harassment that the harasser’s race should not be a factor when determining whether the behavior should be reported.

On a related point, organizations also need to recognize that race might affect how women use policies and procedures. Race might affect targets' satisfaction with the complaint process. Accordingly, organizations need to consider racial issues when creating avenues for reporting complaints. In addition, organizations need to give special care when conducting harassment complaint investigations that cross-racial lines. Since black women are less likely to report harassment, organizations might need to do more to encourage these women to come forward. In addition, they might need to create other avenues for women of color to report harassment. Finally, organizations need to realize that differences in race between harassers and targets might lead to varying degrees of satisfaction with the complaint process. Although our results do not explain why black women are less likely to be satisfied with the complaint process, the results suggest that organizations need to pay close attention to the complaint process when minority women use it. Women who are not satisfied with the complaint process might be more likely to file sexual harassment lawsuits creating legal and operational costs for organizations.

As with any study, there are several limitations that need to be discussed. First, because of using archival data, we could not directly assess black/white harassment. We were able to select black and white female targets, but the survey only asked whether the harasser was of the same or different race. Given the demographic breakdown of the armed services, it is likely that the majority of the cases were black/white harassment, but we cannot say this with absolute certainty. A second limitation is that data were collected in only one type of organization (military). As discussed earlier, the military can serve as an excellent laboratory for studying social phenomena; however, as with any laboratory study, findings might not generalize outside the laboratory. Specifically, because of the unique culture and structure of the military, our results might not generalize to non-military work organizations. A third limitation is that all data were collected at one point in time with one survey instrument, so some of our results might reflect common method variance.

The final and potentially most serious limitation is that our dataset is from 1995; thus, attitudes toward cross-race harassment may have shifted. However, as noted in the introduction, attitudes toward black/white relationships have not shifted dramatically in the past 15 years. The frequency of black/white relationships as a percentage of interracial couples has decreased between 1980 and 2010. Black–white marriages account for less than 1% of all marriages in the United States (Djamba & Kimuna, 2014). Further, Saucier et al. (2010) found that interracial crime was perceived as more severe and warranted harsher sentences than intra-racial crimes. Taken together, it seems likely that the attitudes toward black/white sexual harassment have changed little since these data were collected. It is also interesting to note that although both the military and merits systems protection board has collected more recent data on perceptions of sexual harassment in the military and among federal workers, they no longer ask respondents to identify the race of the harasser. It is unclear what motivated this change. But we suggest that our study is a call to reinstate the question of race in future surveys so the effects of race on the perceptions of and reactions to harassment can be investigated.

Although these limitations exist, we believe that this study provides an essential step toward understanding the effects of race on perceptions of and reactions to sexual harassment. This is especially important as organizations become more demographically diverse, the occurrence of sexual harassment between individuals of different races is likely to increase. We believe that tracing the roots of cross-racial harassment to the historical context of regulating sexual relations between blacks and whites might help both researchers understand and organizations manage the problem of cross-racial sexual harassment.

References

Abramowitz, A., & Teixeira, R. (2009). The decline of the white working class and the rise of a mass upper middle class. Political Science Quarterly, 124(3), 391–422. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-165x.2009.tb00653.x

Apel, D. (2004). Imagery of lynching: Black men, white women and the mob. Rutgers University Press.

Bastian, L. D., Lancaster, A. R., & Reyst, H. E. (1995). Department of Defense 1995 sexual harassment survey, Defense Manpower Data Center. https://doi.org/10.1037/e557792012-001

Benedet, J. (1995). Hostile environment sexual harassment claims and the unwelcome influence of rape law. Michigan Journal of Gender & Law, 3, 125–174.

Berdahl, J. L. (2007). The sexual harassment of uppity women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/e633962013-260

Berdahl, J. L., Cooper, M., Glick, P., Livingston, R. W., & Williams, J. C. (2018). Work as a masculinity contest. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 422–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12289

Berdahl, J. L., & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 426–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.426

Bergman, M. E., & Henning, J. B. (2008). Sex and ethnicity as moderators in the sexual harassment phenomenon: A revision and test of Fitzgerald et al. (1994). Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.152

Berry, D. R., Wall, C. S., Tubbs, J. D., Zeidan, F., & Brown, K. W. (2021). Short-term training in mindfulness predicts helping behavior toward racial ingroup and outgroup members. Social Psychological and Personality Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211053095

Bingham, S. G., & Scherer, L. L. (1993). Factors associated with responses to sexual harassment and satisfaction with outcome. Sex Roles, 29(3–4), 239–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00289938

Bostock, D. J., & Daley, J. G. (2007). Lifetime and current sexual assault and harassment victimization rates of active-duty United States Air Force women. Violence against Women, 13(9), 927–944. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207305232

Buchanan, N. T., & Ormerod, A. J. (2002). Racialized sexual harassment in the lives of African American women. Women & Therapy, 25(3), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1300/j015v25n03_08

Buchanan, N. T., Settles, I. H., & Woods, K. C. (2008). Comparing sexual harassment subtypes among black and white women by military rank: Double jeopardy, the Jezebel, and the cult of true womanhood. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00450.x

Buffone, A. E., Poulin, M., DeLury, S., Ministero, L., Morrisson, C., & Scalco, M. (2017). Don’t walk in her shoes! Different forms of perspective taking affect stress physiology. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 161–168.

Chamberlain, L. J., Crowley, M., Tope, D., & Hodson, R. (2008). Sexual harassment in organizational context. Work and Occupations, 35(3), 262–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888408322008

Chema, R. J. (1993). Arresting “Tailhook”: The prosecution of sexual harassment in the military. Military Law Review, 140, 1–64.

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K. W., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. https://doi.org/10.1086/669608

Cleveland, J. N., & Kerst, M. E. (1993). Sexual harassment and perceptions of power: An under-articulated relationship. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42(1), 49–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1993.1004

Cooper, F. R. (2010). Masculinities, post-racialism and the Gates controversy: The false equivalence between officer and civilian. Nevada Law Journal, 11, 1–43. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1576751

Cooper, F. R., & McGinley, A. C. (2012). Masculinities and the law: A multidimensional approach. University Press.

Cortina, L. M., & Berdahl, J. L. (2008). Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. In Handbook of organizational behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 469–497).

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum (pp. 139–167).

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Department of Defense. (1995). Sexual Harassment Survey by the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness, released July 2, 1996. The Pentagon.

DiTomaso, N., Hearn, J., Sheppard, D. L., Tancred-Sheriff, P. & Burrell, G. (1989). Sexuality in the workplace: Discrimination and harassment. In The sexuality of organization (pp. 71–90). Sage Publications, Inc.

Djamba, Y. K., & Kimuna, S. R. (2014). Are Americans really in favor of interracial marriage? A closer look at when they are asked about black-white marriage for their relatives. Journal of Black Studies, 45(6), 528–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934714541840

Donovan, M. A., & Drasgow, F. (1999). Do men’s and women’s experiences of sexual harassment differ? An examination of the differential test functioning of the sexual experiences questionnaire. Military Psychology, 11(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1103_4

Dowd, N. E., Levit, N., & McGinley, A. C. (2012). Feminist legal theory meets masculinities theory. In F. C. Cooper & A. C. McGinley (Eds.), Masculinities and the law: A multidimensional approach (pp. 25–50). NYU Press. https://doi.org/10.18574/nyu/9780814764039.003.0001

DuBois, C. L. Z., Knapp, D. E., Faley, R. H., & Kustis, G. A. (1998). An empirical examination of same- and other-gender sexual harassment in the workplace. Sex Roles, 39(9/10), 731–749. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018860101629

Dunlap, L. K. (1999). The reform of rape law and the problem of white men: Age-of-consent campaigns in the South, 1885–1910. In Sex, love, race: Crossing boundaries in North American history (pp. 352–372).

Edwards, D. J., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Lowe, R., Evans, N., & Vilardaga, R. (2017). The impact of mindfulness and perspective-taking on implicit associations toward the elderly: A relational frame theory account. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1615–1622.

Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(3), 327–339.

Farley, L. (1978). Sexual shakedown: The sexual harassment of women on the job. McGraw-Hill.

Firestone, J. M., & Harris, R. J. (1994). Sexual harassment in the U.S. military: Individualized and environmental contexts. Armed Forces and Society, 21(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327x9402100103

Firestone, J. M., & Harris, R. J. (2003). Perceptions of effectiveness of responses to sexual harassment in the US military, 1988 and 1995. Gender, Work & Organization, 10(1), 42–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0432.00003

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., & Magley, V. J. (1999). Sexual harassment in the armed forces: A test of an integrated model. Military Psychology, 11(3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1103_7

Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995a). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1704_2

Fitzgerald, L. F., Hulin, C. L., & Drasgow, F. (1995b). The antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: An integrated model. In G. Keita & J. Hurrell, Jr. (Eds.), Job stress in a changing workforce: Investigating gender, diversity, and family issues (pp. 55–73). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10165-004

Fitzgerald, L. F., Swan, S., & Magley, V. J. (1997). But was it really sexual harassment: Legal, behavioural, and psychological definitions of the workplace victimization of women. In W. O’Donohue (Ed.), Sexual harassment: Theory, research and treatment (pp. 5–28). Allyn & Bacon.

Franke, K. M. (1997). What’s wrong with sexual harassment? Stanford Law Review. https://doi.org/10.12987/yale/9780300098006.003.0013

Gelfand, M. J., Fitzgerald, L. F., & Drasgow, F. (1995). The structure of sexual harassment: A confirmatory analysis across cultures and settings. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 47(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.1033

Gettman, H. J., & Gelfand, M. J. (2007). When the customer shouldn’t be king: Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment by clients and customers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 757–770. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.757

Giuffre, P. A., & Williams, C. L. (1994). Boundary lines: Labeling sexual harassment in restaurants. Gender & Society, 8(3), 378–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124394008003006

Goff, P. A., & Kahn, K. B. (2013). How psychological science impedes intersectional thinking. Du Bois Review, 10(2), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1742058x13000313

Golebiowska, E. A. (2007). The contours and etiology of whites’ attitudes toward black-white interracial marriage. Journal of Black Studies, 38(2), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021934705285961

Gruber, J. E., & Smith, M. D. (1995). Women’s responses to sexual harassment: A multivariate analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1704_7

Gutek, B. A. (1985). Sex and the workplace: The impact of sexual harassment on women, men, and organizations. Jossey-Bass.

Gutek, B. A., & Koss, M. P. (1993). Changed women and changed organizations: Consequences of and coping with sexual harassment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1993.1003

Harris, R., & Firestone, J. M. (1996). Testing for double risk of victimization: Sexual harassment in the U.S. military. National Journal of Sociology, 10(2), 1–25.

Hine, D. C. (1997). Hine sight: Black women and the re-construction of American history. Indiana University Press.

Hodes, M. (1999). Sex, love, race: Crossing boundaries in north American history. New York University Press.

Kalof, L., Eby, K. K., Matheson, J. L., & Kroska, R. J. (2001). The influence of race and gender on student self-reports of sexual harassment by college professors. Gender & Society, 15(2), 282–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124301015002007

Kohlman, M. H. (2010). Race, rank and gender: The determinants of sexual harassment for men and women in the military. In V. Demos, & M. Segal (Eds.), Interactions and intersections of gendered bodies at work, at home, and at play (Advances in gender research, Volume 14) (pp. 65–94). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1529-2126(2010)0000014007

Lampman, C., Phelps, A., Bancroft, S., & Beneke, M. (2009). Contrapower harassment in academia: A survey of faculty experience with student incivility, bullying, and sexual attention. Sex Roles, 60(5–6), 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9560-x

Lillis, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2007). Applying acceptance, mindfulness, and values to the reduction of prejudice: A pilot study. Behavior Modification, 31(4), 389–411.

Lind, E. A., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Plenum Publishing Corporation.

Lipari, R. N., & Lancaster, A. R. (2002). Department of defense 2002 sexual harassment survey. Defense Manpower Data Center.

Lucas, J. W., & Baxter, A. R. (2012). Power, influence, and diversity in organizations. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 639(1), 49–70.

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2015). Mindfulness meditation reduces implicit age and race bias: The role of reduced automaticity of responding. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(3), 284–291.

Lueke, A., & Gibson, B. (2016). Brief mindfulness meditation reduces discrimination. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 34.

Maass, A., Cadinu, M., Guarnieri, G., & Grasselli, A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: The computer harassment paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 853–870. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.853

MacKinnon, C. A. (1979). Sexual harassment of working women: A case of sex discrimination. Yale University Press.

Magley, V. J., Waldo, C. R., Drasgow, F., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999). The impact of sexual harassment on military personnel: Is it the same for men and women? Military Psychology, 11(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327876mp1103_5

Martindale, M. (1990). Sexual harassment in the military: 1988. Defense Manpower Data Center.

Matsuda, K., Garcia, Y., Catagnus, R., & Brandt, J. A. (2020). Can behavior analysis help us understand and reduce racism? A review of the current literature. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(2), 336–347.

McDonald, P. (2012). Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: A review of the literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00300.x

McGinley, A. C., & Cooper, F. C. (2012). Introduction: Masculinities, multidimensionality, and the law: Why they need one another. In F. C. Cooper & A. C. McGinley (Eds.), Masculinities and the law: A multidimensional approach (pp. 1–24). NYU Press.

Mendoza, S. A., Skorinko, J. L., Martin, S. A., & Martone, L. E. (2019). The effects of perspective taking implementing intentions on employee evaluations and hostile sexism. Personnel Assessment and Decisions, 5(2), 55–63.

Miller, L. L. (1997). Not just weapons of the weak: Gender harassment as a form of protest for army men. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60(1), 32–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787010

Morral, A. R., Gore, K. L., & Schell, T. L. (2015). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the US military. Volume 2. Estimates for department of defense service members from the 2014 RAND military workplace study. Rand National Defense Research Institute: Santa Monica, CA. https://doi.org/10.7249/rr870.2-1

Morton, P. (1991). Disfigured images: The historical assault on Afro-American women. Praeger.

Munson, L. J., Miner, A. G., & Hulin, C. (2001). Labeling sexual harassment in the military: An extension and replication. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.293

National Organization of Women, Press Release (Thursday, November 14, 1996) NOW Challenges All Branches of The Military to Clean House.

Newkirk, V. R. (2009). Lynching in North Carolina: A history 1865–1941. McFarland.

O’Donohue, W. (1997). Sexual harassment: Theory, research, and treatment. Allyn & Bacon.

Pashak, T. J., Conley, M. A., Whitney, D. J., Oswald, S. R., Heckroth, S. G., & Schumacher, E. M. (2018). Empathy diminishes prejudice: Active perspective-taking, regardless of target and mortality salience, decreases implicit racial Bias. Psychology, 9(6), 1340–1356.

Richter, P. (1997). Army sexual misconduct case prompts racism accusations. Los Angeles Times, March 4 117(9): 2.