Abstract

More than one-third of US children live in families with three or more children. The contemporary impact of larger family size on children’s family resources remains an under-explored point of inequity. Larger family size is not only more common among Black and Hispanic children, but Black and Hispanic children in larger families (Black children, especially so) face higher poverty risks relative to White children in larger families. This analysis uses children’s number of siblings and children’s race and ethnicity to chart the intersectional aspects of disparity in the risk and incidence of poverty and the anti-poverty effects of large federal cash supports, the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. It draws upon 2014–2017 Current Population Survey data and the NBER TAXSIM calculator to apply 2018 tax law, inclusive of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. It reveals well-documented disparities in poverty rates and benefit access and receipt experienced by children of color are further exacerbated by policy structures that discriminate against an under-acknowledged aspect of children’s family life: their family size. Racial bias in policy design that sees tax credit access mechanisms and earnings and benefit structures disproportionately exclude that Black and Hispanic children also disproportionately exclude Black and Hispanic children by their family size. Without reforms that tackle both inequities, policy action that closes the poverty gap between larger and smaller families will see the racial gap in child poverty remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Large family size was an acknowledged risk factor for poverty historically, but it attracts little contemporary attention in the literature. Differences in large family size trends across racial and ethnic groups functioned as an added axis of disparity among children in the US well into the twentieth century before patterns converged in recent decades (Fahey 2017). Despite smaller family norms today, larger family size (defined as 3 or more children) remains an important feature of children’s circumstances in the United States (US). Today, 35% of children under the age of 18 grow up in families of 3 or more co-resident children. In many ways, children in the modern larger family resemble the child population as a whole, but the impact of larger family size on children’s family resources—specifically income—remains an important but under-explored contemporary point of inequity. As this article details, larger family size is not only more common among Black and Hispanic children, but Black and Hispanic children in larger families (Black children, especially so) face higher poverty risks relative to White children in larger families.

The long-term decline in women’s fertility over the twentieth century was first visible among higher income families—opening a temporary gap in family size by income that gave rise to a lasting fixation on lower income family formation (the eventual convergence in family size across income groups never received similar attention) (Fahey 2017). The worst of this attention fed the UK and US eugenics movement, which spread throughout Europe and beyond (Cot 2005; Haas 2008; Leonard 2003). Over 30 US states enacted laws to force the sterilization of socially disadvantaged groups—with Black Americans, Native Americans, and Puerto Ricans as particular targets (Raine 2012; Price et al. 2020). As the US welfare state expanded through the twentieth century—mainly in a means-tested way for families with children—the spotlight on lower income family fertility became increasingly intertwined with public benefits access; the late 1960s saw a US Senator infamously refer to welfare rights activists as ‘brood mares’ (Minoff 2020). Social policy eventually turned towards lone parenthood, but family size policy and racial and ethnic discrimination links remained. Purported concern over ‘out of wedlock’ births informed the Republican Party’s Contract with America and led to President Clinton’s 1996 welfare reform, itself culmination of years of heavily racialized and gendered debate (Orloff 2002)—a core tenet of which was the denial of cash assistance to new babies born.

The set of income supports available today, and the ways in which access and outcomes intersect with children’s race and ethnicity and family size, are borne out of this legacy. To investigate the contemporary intersection, this analysis takes two of the current largest federal income supports—the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit—to understand the ways in which they serve children across racial and ethnic groups and larger and smaller families.

Family Size and Family Policy Today

While lacking a thorough investigation in the US in recent decades, research in high-income peer nations has increasingly flagged family size as a poverty concern for children. Cantillon and Van den Bosch (2002), in an 11-European country study, found the poverty risk of households with three or more children on the same par as those headed by a lone parent. O’Connell et al (2019) find large families, along with lone parent families, to be at highest risk of food insecurity in the United Kingdom (UK). Bradshaw et al (2006), as well as Willitts and Swales (2003) and Iacovou and Berthoud (2006) for the UK Department of Work and Pensions, all identify large family size as a meaningful contributor to child poverty in the UK at the start of the twenty-first century. In mid-2020, the Irish Department of Children and Youth Affairs released a new income and poverty baseline identifying the ‘number of children in the household’—specifically, three or more children—as a key poverty risk.

Family size has been under-explored as a contemporary poverty risk in the US, but it remains a factor in public policy. The Earned Income Tax Credit is capped at three children (though this was expanded from a two-child maximum in 2009) and the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit remains capped at two children. The Child Tax Credit ostensibly offers per-child benefits, but—as this article discusses—earnings requirements mean large families have to earn more than small families to receive the full benefit (Curran and Collyer 2020). As of 2018, fourteen states maintained a family cap as part of their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, disqualifying any child born after program receipt had begun to be included in the benefit payment (Thomhave 2018). Family caps continue to be proposed with respect to cash assistance: although warnings child poverty could reach its highest level in 50 years amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (Parolin and Wimer 2020), the US Congress repeatedly proposed capping emergency payments at a maximum of three children. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) adjusts benefits by family size, but larger families are more likely to be extramarginal consumers—their food spending is less than or equal to the amount of SNAP benefits received and this is likely due to budget constraint rather than preference (Johnson et al 2018; Hoynes et al 2015). Gundersen et al. (2018) flag large families as a group for consideration in any future SNAP reform.

Contribution of This Study

Research has documented the ways in which access to the safety net is unequal across racial and ethnic groups (Allard 2008; McDaniel et al 2017). Family size-related elements in federal safety net programs, as identified above, likely also mean that children in larger families are not served as well as they could be by current public policy. This analysis employs a dual lens of children’s family size and children’s race and ethnicity to identify any intersecting aspects of disparity in the risk and incidence of poverty and the anti-poverty effects of key cash supports. This investigation has a particular interest in whether the well-documented disparities in benefit access and receipt and poverty rates experienced by children of color in the US are further impacted by an under-acknowledged aspect of children’s family life: their family size.

The specific focus here is on the two largest and nationally uniform cash transfer programs for children, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC). Together, these tax credits kept 7.5 million people from poverty in 2019, including 4 million children, and lessened the severity of poverty for millions more (Fox 2020). Research indicates both credits help advance racial equity, particularly among women and children of color, as they serve larger proportions of both (Huang and Taylor 2019; Sherman and Mitchell 2017). At the same time, children’s rate of receipt remains uneven across racial and ethnic groups. At the start of the twenty-first century, low-income Hispanic families were less than half as likely than low-income non-Hispanic families to have heard of or received the Earned Income Tax Credit (Ross Phillips 2001). Hispanic families saw decreased participation over the next decade (Jones 2014) and continue to be less likely to receive the EITC today (Thomson et al 2020). One-third of all children do not receive the full Child Tax Credit because their parents earn too little, but children of color are twice as likely to be left out; over 50% of all Black and Hispanic children are left behind, compared to 23% of White, non-Hispanic children (Collyer et al. 2019).

This analysis examines the impact of these programs in their current form. It also examines the impact of a set of proposed, but not yet enacted, enhancements in order to understand the extent to which various proposed changes to children’s cash supports would address any compounded disparity. The findings add to our understanding of how structural reforms of existing public programs can improve incomes and equity for children and their families.

Research Questions

To understand the efficacy of cash supports by children’s race and ethnicity and their family size, this analysis centers on two key questions:

-

(1)

Among children with larger family size living below the poverty line, how do the risk and incidence of poverty differ for children across racial and ethnic groups?

-

(2)

How do key federal cash supports (here: family tax credits) impact children in larger families compared to smaller families—and larger families of color in particular?

Data and Methods

Data

This analysis draws upon a nationally representative sample of children under the age of 18 from the US Current Population Study Annual Social and Economic Supplement (CPS ASEC) accessed through the University of Minnesota Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) CPS database (Flood et al. 2020). A four-year sample of 2014–2017 calendar year information (pulled from the 2015–2018 March CPS ASEC releases) is used. The CPS ASEC data are adjusted with TAXSIM27 (Feenburgh and Coutts 1993). Specifically, TAXSIM27 is used to apply tax policy under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017; therefore, all baseline poverty rates across age groups assume receipt of current law Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit, post-TCJA changes. Because this analysis uses 2018 as the tax year—the first year TCJA was in effect—income data from all years are inflation adjusted to 2018 dollars (US Bureau of Labor 2020). It uses the person-level ‘asecwt’ weight for all descriptive results.

Theoretical Approach

This analysis examines family size from the children’s point of view—specifically, in terms of the number of co-resident children in the home. To the extent family size is examined today, women’s fertility is the dominant focus. But the traditional practice of measuring family size from an adult perspective results in a stark undercount of large family life from the point of view of children. To take recent US data (Shkolnikov et al. 2007), 30% of women just past the point of childbearing in 2007 had borne three or more children; yet among the children of these women, more than half (56%) were in families of three or more siblings. The underlying concept here was first set out by Preston (1976) who identified that, as a matter of group averages, children’s family size (i.e.. sibling size or sibsize) cannot be read off from the family size of their parents—the former is larger than the latter, sometimes by a wide margin.

Table 1 demonstrates the way in which family-level figures understate the prevalence of large family size among children. One-fifth (20%) of families with children are larger families—those with three or more co-resident children under the age of 18. Of all children under the age of 18, however, more than one-third (35%) live in larger families. A child-centered measure better captures the fact that larger family size is a more common family form for children than is often realized.

For children, this is important because their sibsize represents the number of siblings with whom family resources (parental time, energy, material items, and income) must be shared. Resource dilution has a long history in the literature (Becker 1964; Blake 1989) and is implicitly accounted for in contemporary income poverty measurement through the matter of equivalence, but not usually with a focus on the impact of large family size today. Gibbs et al (2016) proffer an update to the traditional resource dilution model that links large family size with more negative child outcomes: family size effects on children are tempered by the community and state-level contexts in which they live and public policy has a particular impact.

As such, this analysis is interested in the intersection of family size and public policy—with a particular look at how this plays out for children’s family income across racial and ethnic groups, given the well-documented history of inequities in access to public supports, including the EITC and CTC, and the higher poverty rates experienced by children of color (Ross Phillips 2001; Jones 2014; Collyer et al. 2019). The value of the family tax credits received is calculated at the tax unit level using TAXSIM27, but for the purposes of determining the impact on children’s poverty status, the analysis uses the sum of each tax unit’s EITC and CTC values within the broader Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM (described below), family unit; it is understood that SPM family units can include more than one tax unit (Parolin et al. 2020).

Methods

As the main outcome measure of interest, the dependent variable is income poverty status, as measured by the US SPM—a framework better suited to capturing the effects of public policy on family resources than the US official poverty measure (Fox and Renwick 2016; Fox 2019; Fox et al 2015; Wimer et al 2016). The main independent variable(s) of interest in the descriptive results are children’s family size and children’s race and ethnicity, examined both individually and in combination. Descriptive tables detail the risk and incidence of poverty across children’s family categories, as well as the effect of current and proposed federal family tax credits on child poverty rates by children’s race and ethnicity and children’s family size.

This analysis defines children’s family size as the number of co-resident children under the age of 18 in the home. It understands children under 18 to be those classified as dependents for tax purposes and the household to be the family tax unit, both categories as identified by tax pointers within the CPS ASEC data. It remains an open question in the literature as to what constitutes a ‘large’ family today. The definition of ‘larger’ family size, here, is set at three or more co-resident children. Three children, as seen in Table 1, are above the US mean children’s family size and coincide with the family size threshold in the Earned Income Tax Credit under current law. The three-child threshold also has support in the literature from Willitts and Swales (2003) and Kemp et al (2004), among others, though Iacovou and Berthoud (2006) and Curran (2019) make the case for a four-child threshold. Bradshaw et al (2006), in a national review of child poverty in large families in the UK on behalf of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, asserts a preference for the large family definition at four or more children, but—in recognition of the flexibility in the term—reports results for families with three or more and four or more children. This article takes a similar approach, using an umbrella category of ‘larger’ to represent families with three or more dependent children under the age of 18 in the home as compared to smaller families (those with 1 or 2). However, it also breaks out ‘larger’ family results into those with three children only and those with four children or more to identify any underlying trends. Table 2 identifies the sample size used in the analysis, across years, race and ethnicity, and family size.

With respect to race and ethnicity, differences between children in smaller and larger families are not substantial—though those in larger families today are more likely to identify as Hispanic. The race and ethnicity variable is based upon the terms used in the CPS ASEC. Race and ethnicity, on the whole, are imperfect variables (Hogan and Eggebeen 1995; Pew Research Center 2012) but are used here in an acknowledgement that they often align with variations in child material well-being and access to public supports due to historic and continued structural racism and discrimination. Four categories are used: ‘Black,’ ‘Hispanic,’ ‘Other,’ and ‘White’; the ‘Other’ category also employs an imperfect term and a broad one, encompassing individuals who identify as Asian, Native American, multi-racial, and more. Future work in this area, using data with sample sizes that allow for a specific look at smaller population groups and regional patterns, where relevant, would be a useful complement to this analysis. Results are not interpreted as causal (i.e., does a particular race/ethnic category cause large family size or income poverty status) (Holland 2008; Bonilla-Silva and Zuberi 2008); rather they function as contextual elements in the discussion of patterns of association regarding the family features most associated with contemporary large family size and children’s experience of large family income poverty today.

Additional independent variables featured in the descriptive results include family structure, maternal education, maternal employment, maternal immigration status, and geographic region. The first three are socio-demographic family characteristics long identified in the literature as indicators of socio-economic resources and as correlates of both family size and family income (Brooks-Gunn and Duncan 1997; Sigle-Rushton and Waldfogel 2007; Fahey 2017; Carlson and Furstenberg 2006); the latter two, in addition to race and ethnicity, function as an additional set of family features associated with variations in material well-being and children’s access to public supports (Kamerman et al 2003; O’Hare et al 2012; Curtis and Waldfogel 2009; Hernandez et al. 2010). Maternal age would be an additional independent variable of interest but was not taken up due to limitations in the data (the CPS ASEC reports only maternal age at the birth of her eldest child currently in the home, rather than maternal age at first birth).

Results

Larger Family Size is More Common Among Black and Hispanic Children

Table 3 charts the prevalence of large family size for children across racial and ethnic groups. Approximately 40% of children in Black and Hispanic families live in families with three or more children compared to close to 30% for children in White and all other family groups. Greater proportions of Black and Hispanic children also live in families with four or more children in the home.

A broader look was also taken at the socio-economic characteristics of children in larger and smaller families (results not presented here). Similar to the findings of Curran (2019), children in larger families are spread in similar fashion across geographic regions. Children in larger families are also more likely (by a difference of 6 percentage points) to live in two-parent families. Larger families report lower levels of maternal education and maternal work compared to smaller families. But perhaps most notable is difference in SPM poverty levels among children in smaller families (12.9%) and children in larger families (17.8%)—a difference of 5 percentage points (and a 28% gap) across the two groups.

Black and Hispanic Children in Larger Families Face Increased Risk of Poverty

Table 4 examines the risk of SPM poverty for all children in the US across different family sizes and racial and ethnic groups.

The risk of SPM poverty among children in larger families (18%) is higher than in smaller families (13%). This is true across racial and ethnic groups, with a more pronounced family size poverty gap for Black and Hispanic children. Looking within larger families, it is clear than SPM poverty rates among children in four-plus child families which are consistently higher than rates in three-child families—likely contributing to a portion of the family size poverty gap for children across groups. Even absent these family size differences, though, a racial poverty gap for children is evident: in both larger and smaller families, the SPM poverty rate among Black and Hispanic children is approximately two and a half times higher than it is for White children. Black children in larger families face the highest poverty risk of all groups examined. As such, it is of interest to understand how anti-poverty policy intersects with both children’s race and ethnicity and children’s family size.

Larger Family Size is a Common Family Feature for Children in Families Below the Poverty Line

To understand more about the family features of children in poverty, Table 5 looks specifically at the population of children under 18 below the SPM poverty line. It compares key contemporary socio-economic characteristics of children in larger and smaller families and those in different racial and ethnic groups by the set of ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ independent variables identified earlier.

For children in families with incomes below the SPM poverty line, larger family size is a common family feature. Table 5 shows that more than 40% of all children in poverty live in larger families, including 39% of White children in poverty, 43% of Black children in poverty, and just about half (48%) of Hispanic children in poverty. Of those in larger family poverty, the split between three-child and four-plus child families is almost even. This is relevant for public policy, as one of the largest anti-policy programs for children—the Earned Income Tax Credit—currently recognizes only the first three children in the family and the benefit for three-child families does not increase proportionally (as noted earlier, recognition of the third child has also only been in place for about a decade, when the two-child maximum was expanded in 2009).

Children’s Access to Anti-poverty Tax Credits Varies by Children’s Race and Ethnicity and Family Size

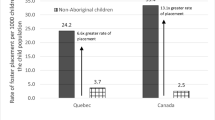

The next set of results examines the poverty reduction impact of the two largest federal family tax credits, the EITC and the CTC by children’s race and ethnicity and family size. For context, each operates uniformly nationwide, but treats children in families of different sizes differently within their credit structures—indeed, the structures of both tax credits, as seen in Figs. 1 and 2, work to the disadvantage of children with larger family size. In particular, larger families must earn more than smaller families to access the maximum credit amounts, despite the fact that larger families do not necessarily earn more than smaller families (Curran 2019; Curran and Collyer 2020).

Image reproduced with permission from Curran and Collyer (2020:2)

Phase-in of Child Tax Credit Value by Income and Family Size (Joint Tax Filers).

For children, the earnings structure of the Child Tax Credit is arguably the most problematic element. Excluding those on the lowest incomes hampers the credit’s anti-poverty effectiveness, while also leaving out children in particular family types and circumstances. Recent work from Columbia University (Collyer et al. 2019; Collyer 2019) demonstrates the ways in which the CTC earnings requirement and phase-in disproportionately exclude Black and Hispanic children, children in single-parent households, and those in certain regions of the country (e.g., South). Less well known is that fact that, despite ostensibly offering per-child benefits, the CTC also disadvantages children in larger families, leaving them out at greater rates. Nearly half of all children in larger families, compared to less than one-third in smaller families, do not receive the full Child Tax Credit because their earnings fall below the income thresholds for their family size (Curran and Collyer 2020). As seen in Fig. 1, a family with two adults and two children needs at least $36,000 in earnings to access the full Child Tax Credit; if they added a third child to their family, they would require almost 20% more in earnings ($42,000) in order to maintain access to the full credit. A family with four children needs to earn 30% more than a family with two children in order to access the full credit.

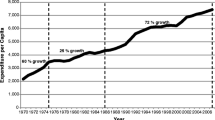

As noted earlier—and like the CTC—children’s receipt of the EITC remains uneven across racial and ethnic groups. Hispanic children, in particular, are less likely to access it. In contrast to the CTC, the EITC has long operated under a family cap structure. It currently recognizes just four family size types: those with zero, one, two, and three dependents (with a higher income threshold in each category for married families compared to families who file as single or head of household tax units). Due to the phase-in structure of the current credit, families with two or more children must earn closer to 30% more than families with one child to access the maximum credit amount ($14,800 versus $10,540 in earnings, respectively). At the same time, the maximum credit begins phasing out at the same income threshold ($19,330) for all families of children, regardless of size. As Fig. 2 shows, this results in multi-child families having a narrower window (in terms of their level of earnings) in which they can access the full Earned Income Tax Credit than families with one child. The maximum credit amounts also vary by family size, to the detriment of children in larger families. Moving from a family of one child to a family of two children, the maximum credit amount increases by 40% ($3,584 to $5,920). Moving from a family of two children to a family of three or more children, however, the maximum credit amount increases by just 11 percent ($5,920 to $6,660).

Anti-poverty Impact of Tax Credits Vary by Children’s Race and Ethnicity and Family Size

Figure 3 looks at the anti-poverty impact of current law, identifying the effect of each credit individually and in combination. Each column represents the different levels of SPM poverty for children in smaller and larger families across racial and ethnic groups under a series of scenarios: current law (e.g., existing version of the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit); without the Child Tax Credit; without the Earned Income Credit; or the absence of both credits together.

Figure 3 shows that the two credits together actually reduce poverty at greater rates for larger families than smaller ones: without them, smaller family poverty would be 29% higher than it currently is and larger family poverty would be 36% higher. Even so, distinct disparities in the poverty rates by children’s race and ethnicity and family size remain.

Potential Anti-poverty Impact of Proposed Tax Credit Changes

A number of proposed policy changes exist to enhance both credits. Proposed changes to the Child Tax Credit gaining recent traction center around the removal of the earnings requirement (as shown in Fig. 1) to transform the credit into a fully refundable one. This change would see that all families below the income phase-out income threshold receive the maximum benefit per child. Other proposals would couple a fully refundable structure with higher maximum benefit levels for children who receive it (NAS 2019; Shaefer 2018).

Similar to Fig. 3, each column in Fig. 4 represents the different levels of SPM poverty for children in smaller and larger families across racial and ethnic groups under two versions of proposed, but not enacted, alternatives to the Child Tax Credit. Option 1 (‘Alt CTC v1′) would remove the Child Tax Credit earnings requirement, delivering a fully refundable $2000 credit to all income-eligible dependents under 17 under current law. Option 2 (‘Alt CTC v2′) would remove the Child Tax Credit earnings requirement and couple this with increased maximum credit amounts (here, along the lines of the American Family Act, S.690/H.R.1560 in the 116th US Congress; a one-year version was passed by the US House of Representatives in May 2020 as part of the HEROES Act of 2020 (H.R.6800)) of a fully refundable credit valued at $3000 per income-eligible dependent aged 6 to 16 and $3600 for those under 6 years old. These proposals are modeled here because they specifically tackle the structural barriers for larger families (e.g., the earnings requirement as seen in Fig. 1). Modeling existing proposals for the Earned Income Tax Credit were considered, but no popular proposal at the moment currently tackles the particular issues in this credit related to family size—here: the family size cap, disparity in the earnings phase-in, or equity in the maximum benefits across families with children. This issue is taken up further in the discussion.

Key Policy Findings

Proposed policy alternatives for the Child Tax Credit—for example, increasing eligibility and credit amounts, as seen in Fig. 4—would make substantial progress for children across demographic groups and eradicate the family size gap in poverty that currently exists. Making the Child Tax Credit fully refundable (Option 1) would reduce larger family poverty rates by one-third and, in doing so, equalize larger and smaller poverty rates for children in each racial and ethnic group. The overall racial gap in child poverty, however, would remain. Specifically, child poverty among Black and Hispanic children would still be more than twice the rate of White children. Combining full refundability with higher benefit levels (Option 2) would cut smaller family poverty by over one-quarter and larger family poverty by half—resulting in SPM poverty rates for children in larger families across all racial and ethnic groups that are lower than those in smaller family ones. Again, however, the poverty gap for children by race and ethnicity would remain.

Discussion

Risk and Incidence of Larger Family Poverty by Children’s Race and Ethnicity

Larger family size emerges as both a common feature of childhood (more than one-third of all those under 18 live in families with three or more children) and of child poverty (more than 40% of children below the poverty line do). As such, there is case to be made for family size to feature more prominently within the contemporary research and policy agenda for children. Larger family size is also a prevalent family form for children across racial and ethnic groups, though it is more common for Black and Hispanic children. But how children fare in larger families—specifically in terms of income poverty—emerges as a sharp point of divergence. Larger family size is also a common family feature for families with incomes below the poverty line, but Black and Hispanic children in larger families face more poverty risk than White children in larger families. And Black children in larger families face the highest poverty risk of all groups examined, making access to, and the efficacy of, anti-poverty policy—here: in the form of the two largest family tax credits—crucial for these children.

The Efficacy of Cash Supports by Children’s Race and Ethnicity and Family Size

With respect to the impact of policy—here: the two largest federal family tax credits, the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit—both do important work in reducing child poverty across racial and ethnic groups and across family sizes. Yet both credits also treat children in families of different sizes differently within their credit structures—to the distinct disadvantage of children in larger families. Larger families must earn more than smaller families to access the maximum credit amounts; yet, larger families do not necessarily earn more than smaller families (Curran 2019; Curran and Collyer 2020). In leaving out those on the lowest incomes and requiring higher earnings from larger families to access the maximum credit, the CTC compounds disadvantage. Black and Hispanic children are more likely to live in families with lower incomes, are more likely to live in larger families, and those in larger families face the highest poverty risk. Current CTC policy does reduce larger family poverty in general, but notable racial and ethnic disparities in poverty rates for children remain. Policy alternatives that would increase eligibility and benefit levels would support children across family sizes and racial and ethnic groups, but a racial gap in poverty would remain.

The current structure of the EITC works to the disadvantage of children in larger families in a different way. By capping the credit at a maximum of three children, children higher in the birth order are effectively unrecognized by one of the primary vehicles for delivering family income support in the US. This cap places additional strain on all children in large families (with 4 + children), as the credit meant for three children must stretch further than designed. The narrower earnings window at which larger families are eligible for the maximum EITC benefit and the uneven credit increases between family sizes (e.g., a 40% increase in the maximum credit value when moving from a 1-child family to a 2-child family, but only an 11% increase in the maximum credit value when moving from a 2-child family to a 3-child family) does not adequately reflect the resource needs of families of larger size, while also resulting in children with siblings being penalized—with respect to EITC receipt—compared to children without.

As noted, existing proposals to improve the Earned Income Tax Credit do not tackle these family size discrepancies and are therefore not modeled here. This is an area worthy of future exploration. In thinking about to redress this in future policy reform, Zelenak (2004) provides a relevant overview of the ways in which the Earned Income Tax Credit interacts with family size, how an acknowledgement of this issues necessitates a broader reckoning with the purpose and design of the credit, and how the alternative versions of the credit—through adjustments to maximum credit amounts and credit phase-in rules, among other things—might better account for the needs and realities of larger family life so that it can function as a truer and more effective family size adjustment to the minimum wage. Given the disparities in the risk and incidence, as well as dynamics, of larger family poverty across children’s racial and ethnic groups, a race-conscious lens would be an important element of this analysis (Gennetian and Yoshikawa 2020).

Understanding Disparities and Opportunities for Equity

As a precondition for children’s access, the earnings requirements built into these two family tax credits essentially function as an implied form of work requirements. Minoff (2020) describes the history and evolution of work requirements across US social safety net programs with a specific look at the ways in which contemporary regulations have links to racialized, at times explicitly racist, origins. This analysis identifies the ways in which the earnings and credit structure of both credits work to the particular disadvantage of children in larger families and that these effects are compounded for Black and Hispanic children compared to their White peers.

Compared to smaller families, maternal employment in larger families is lower. Within larger families, maternal work rates drop as family size increases (60% of mothers in three-child families are in work and just under half of mothers in families with four or more children are) (see Curran 2019 for more). Caregiving is, of course, an obvious issue and these findings prompt questions on the nexus of work and family across demographic groups, from the availability and affordability of child care, the opportunity costs of employment, and the responsiveness of social policy to the realities of larger family life and larger family needs (the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, for example, is not only capped at two children but also remains largely inaccessible to lower and moderate income families paying for child care due to its lack of refundability).

Maternal work rates among children in larger families in poverty are roughly half that of those for children in larger families in general. In this light, earnings requirements become an added challenge in terms of accessing needed support. Additional barriers exist for Black and Hispanic children. Black children in larger families below the poverty line have the highest proportion of single-headed households; they also have the highest maternal work rates across racial and ethnic groups. But earnings requirements do not account for race and gender disparities in pay (NWLC 2020; Paul et al 2018), nor the imbalance between these pay gaps and the costs of employment and care—as of 2017, for example, average child care costs exceeded 20% of average earnings among Black women (DuMonthier et al. 2017). Hispanic children in larger families in poverty report the highest incidences of mothers who are not US citizens which also impacts employment access and earnings. The data used here does not report documentation status among non-citizens, but immigration status here is included as a proxy for access to public supports. Even families headed by legal resident non-citizen parents have reduced access—as a result of both explicit restrictions and chilling effects—to cash assistance, nutrition assistance, health care, and more (Haley et al 2020).

Larger family size is common across all US regions, but research has shown that uniform access to the safety net is not (O’Hare 2012; Parolin 2019). With respect to the geography of larger family size, larger family size is common across all US regions (Curran 2019, as well as results not included here); Curran and Collyer (2020) find at least one-quarter of children in every state live in larger families and in many states, it is between one-third and one-half. Large family poverty is more concentrated: Table 5 shows that child poverty in larger families among Black children is the highest in the South and among Hispanic children and those in the ‘Other’ category in the West. Child poverty in larger families among White children has the most even spread across regions, but is also highest in the South. To this end, future research on the efficacy of the safety net for children in larger families could benefit from a more regional focus—particularly to understand the intersection of family size, race, and place in the delivery of public supports.

Conclusions

Family size and race and ethnicity are both important features of children’s family circumstances in the US today in that both (separately and in combination) are linked to variation in child poverty outcomes. Family size should be better accounted for in family and poverty research and policy analysis and development today. Specifically, the analysis shows here the ways in which it exacerbates disparities in poverty rates among children across racial and ethnic groups and the ways in which contemporary public policy is unresponsive to—and indeed, often penalizes—this common feature of childhood.

At the same time, it is clear that addressing the gap in poverty by family size is not enough to adequately address underlying racial and ethnic inequities for children. Proposed policy alternatives for the Child Tax Credit, for example that would result in the program more closely resembling a national child allowance would make substantial progress in reducing poverty for children across demographic groups and—importantly—eliminate the poverty gap by children’s family size, but a poverty gap by children’s race and ethnicity would remain. As such, these findings lend support to existing calls for added elements to policy reform that more specifically help address the long history of racial inequity in the US that remain evident in children’s outcomes and close the racial gap in child poverty.

Limitations and Considerations for Future Work

This analysis is not a comprehensive assessment of the ways in which the US social safety net works for children across family sizes and across racial and ethnic groups. Its narrow focus examines the two largest federal family tax credits, specifically because they represent cash income for families, are proven to have a substantial impact on child poverty (Fox 2020), and operate uniformly across the country. SNAP, TANF, and housing assistance (public housing or Sect. 8 vouchers, for example) are all examples of additional programs worthy of investigation in this framework and modeling proposed changes in these programs—in combination with the Child Tax Credit alternatives looked at here and the inclusion of an alternative Earned Income Tax Credit structure for larger families—would likely shed additional light on the interplay between children’s family size and race and ethnicity in general, as well as what policy reforms can help close the racial and ethnic gap in poverty more specifically. Research indicates that particular combinations of safety net programs (e.g., tax credits plus housing assistance) are additive in their poverty reduction impact (Collyer et al 2020). In other words, each program plays a particular poverty reduction role—rather than one policy effect replacing the other when combined. As such, including these programs in future investigations could lend additional nuance and insight to the observations made here. To do so properly, though, state variation in these three policy areas (including differences in benefit levels and family caps) needs to be taken into account.

This analysis is also limited in that it paints a portrait of larger family size and larger family poverty across children’s race and ethnic groups prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent economic crisis. Congressional action taken early in the crisis to mitigate the worst of the economic effects was time limited and access was inconsistent across the country, resulting in increased hardship and food insecurity—particularly among families with children, with Black and Hispanic families hit particularly hard—and the potential for increases in income poverty (Parolin and Wimer 2020; Parolin et al. 2020; Bitler et al. 2020). Measures tracking how families fare amidst the crisis have not often been broken out by family size, but given the notably higher rates of income poverty among children in larger families in the years pre-pandemic, it is likely children in larger families face elevated risks of hardship now. Further exacerbating the situation, particularly for Hispanic children in larger families, there were immigrant exclusions from emergency cash assistance in the early rounds of federal pandemic relief packages and unemployment benefit expansions. Congressional negotiations around pandemic emergency assistance in the spring and summer of 2020 also saw repeated proposals to cap emergency cash payments at a maximum of three children. Additional pandemic-related assistance may still be delivered, and family caps remain a potential concern.

Moving forward—and across all areas of the social safety net—centering children in policies geared towards them, rather than conditioning children’s access on parental characteristics (e.g., parental income, parental work, number (and marital status) of parents at home, and more) or capping benefits based on characteristics out with their control (e.g., sibling size, birth order, immigration status, location, and more) represent key considerations in tackling variation in children’s outcomes and building equity.

Data Availability

Public-use data accessed through the University of Minnesota Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) CPS database.

References

Allard, S. (2008). Out of reach: Place, poverty, and the New American Welfare State. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Becker, G., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). Interaction between quantity and quality of children. In T. W. Schultz (Ed.), Economics of the family: Marriage, children and human capital (pp. 81–90). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Becker, G., & Tomes, N. (1979). An equilibrium theory of the distribution of income and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Political Economy, 87(6), 1153–1189.

Becker, G., & Tomes, N. (1986). Human capital and the rise and fall of families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4(3), S1–S39.

Bitler, M., Hoynes, H., & Schanzenbach, D. (2020). The social safety net in the wake of COVID-19. Brookings papers on economic activity, BPEA Conference Drafts (25 June). Washington DC: The Brookings Institution.

Blake, J. (1981). Family size and the quality of children. Demography, 18, 321–342.

Blake, J. (1989). Family size and achievement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Bonilla-Silva, E. & Zuberi, T. (2008). Toward a definition of white logic and white methods. In T. Zuberi & E. Bonilla-Silva (Eds.), White logic, white methods: Racism and methodology (pp. 3–31). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Bradshaw, J., Finch, N., Mayhew, E., Ritakallio, V., & Skinner, C. (2006). Child poverty in large families. Bristol: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Brooks-Gunn, J., & Duncan, G. J. (1997). The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children: Children and Poverty, 7(2), 55–71.

Cantillon, B. & Van den Bosch, K. (2002). Social policy strategies to combat income poverty of children and families in Europe. LIS Working Paper Series, No. 336. Retrieved Sept 9, from http://www.lisdatacenter.org/wps/liswps/336.pdf.

Carlson, M. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. (2006). The prevalence and correlates of multipartnered fertility among urban US Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(3), 718–732.

Collyer, S. (2019). Children losing out: The geographic distribution of the federal child tax credit. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 3(9). New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Collyer, S., Harris, D., & Wimer, C. (2019). Left behind: The one-third of children in families who earn too little to get the full child tax credit. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 3(6). New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Collyer, S., Wimer, C., Curran, M., Friedman, K., Hartley, R.P., Harris, D., & Hinton, A. (2020). Housing vouchers and tax credits: Pairing the proposal to transform section 8 with expansions to the EITC and the child tax credit could cut the National Child Poverty rate by half. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 4(9). New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Cot, A. L. (2005). Breeding out the unfit and breeding in the fit: Irving fisher, economics, and the science of heredity. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 64, 793–826.

Curran, M. (2019). Large family, poor family? The family resources of children in large Families in the United States, United Kingdom, and Ireland. Doctoral thesis, University College Dublin. Available upon request.

Curran, M. & Collyer, S. (2020). Children left behind in larger families: The uneven receipt of the federal child tax credit by children’s family size. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 4(4). New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Curtis, M., & Waldfogel, J. (2009). Fertility timing of unmarried and married mothers: Evidence on variation across US cities from the fragile families and child wellbeing study. Population Research and Policy Review, 28(5), 569–588.

DuMonthier, A., Childers, C., & Milli, J. (2017). The status of Black Women in the United States. Washington DC: National Domestic Workers Alliance and Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Fahey, T. (2017). The Sibsize revolution and social disparities in children’s family contexts in the United States, 1940–2012. Demography, 54(3), 813–834.

Feenberg, D. R., & Coutts, E. (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12(1), 189–194.

Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J.R. (2020). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 7.0 . Minneapolis: IPUMS.

Fox, L. (2019). The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2018. U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports. Washington DC: US Census Bureau.

Fox, L. (2020). The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2019. U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports. Washington DC: US Census Bureau.

Fox, L., & Renwick, T. (2016). The Supplemental Poverty Measure: 2015. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports: U.S.

Fox, L., Wimer, C., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., & Waldfogel, J. (2015). Waging war on poverty: Poverty trends using a historical supplemental poverty measure. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 34(3), 567–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21833.

Gennetian, L. & Yoshikawa, H. (2020). Race and racism: The blind spot in research on poverty and child development. Child and Family Blog (September) . Retrieved October 1, 2020 from https://www.childandfamilyblog.com/child-development/racism-blind-spot-on-poverty-child-development/.

Gibbs, B., Workman, J., & Downey, D. B. (2016). The (conditional) resource dilution model: State- and community-level modifications. Demography, 53, 723–748.

Gundersen, C., Kreider, B., & Pepper, J. V. (2018). Reconstructing the supplemental nutrition assistance program to more effectively alleviate food insecurity in the United States. RSF The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4(2), 113–130.

Haas, F. (2008). German Science and Black Racism—Roots of the Nazi Holocaust. FASEB Journal, 22, 332–337.

Haley, J., Kenney, G., Berstein, H., & Gonzalez, D. (2020). One in five adults in immigrant families with children reported chilling effects on public benefit receipt in 2019. Washington DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved September 26, 2020 from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102406/one-in-five-adults-in-immigrant-families-with-children-reported-chilling-effects-on-public-benefit-receipt-in-2019_1.pdf.

Hernandez, D. J. (2010). Internationally comparable indicators for children of immigrants. Child Indicators Research, 3(4), 409–411.

Hogan, D. P. & Eggebeen, D. J. (1995). Demographic change and the population of children: Race/ethnicity, immigration, and family size. In Indicators of child well-being: conference papers. Volume III: Cross-cutting issues; population, family, and neighborhood; social development and problem behaviors. Institute for Research on Poverty Special Report no. 60c, 45–62.

Holland, P. W. (2008). Causation and race. In T. Zuberi, & E. Bonilla-Silva (Eds.) White logic, white methods: Racism and methodology (pp. 93–110). Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Hoynes, H. W., McGranahan, L., & Schanzenbach, D. W. (2015) SNAP and food consumption. In J. Bartfield, C. Gundersen, T. M. Smeeding, & J. P. Ziliak (Eds.) SNAP matters: How food stamps affect health and well-being. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Huang, C. & Taylor, R. (2019). How the federal tax code can better advance racial equity. Washington DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved September 21, 2020 from https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-better-advance-racial-equity#_edn58.

Iacovou, M. & Berthoud, R. (2006). The economic position of large families. Research Report No. 358. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

Johnson, D., Schoeni, R., Tiehen, L., & Cornman, J. (2018). Assessing the effectiveness of SNAP by examining extramarginal participants. Research Report 18-889. Population Studies Center, University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

Jones, M. (2014). Changes in EITC eligibility and participation, 2005–2009, Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications (CARRA) Working Paper Series, #2014-0. Washington DC: US Census Bureau.

Kamerman, S., Neuman, M., Waldfogel, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). Social policies, family types, and child outcomes in selected OECD countries. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Paper No. 6. Retrieved August, 2019 from https://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/625063031050.pdf?expires=1565794827&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=30B9B494E607EBB3ED76629970FAE391.

Kemp, P., Bradshaw, J., Dornan, P., Finch, N., & Mayhew, E. (2004). Routes out of poverty. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Leonard, T. C. (2003). More merciful and not less effective: Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era. History of Political Economy, 35, 687–712.

McDaniel, M., Woods, T., Pratt, E., & Simms, M. (2017). Identifying racial and ethnic disparities in human services: A conceptual framework and literature review. OPRE Report #2017-69. Washington DC: OPRE, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Minoff, E. (2020). The racist roots of work requirements. Washington DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy. Retrieved September 26, 2020 from https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Racist-Roots-of-Work-Requirements-CSSP-1.pdf.

National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS). (2019). A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington DC: The National Academies Press. Retrieved September 30, 2020 from https://www.nap.edu/read/25246/chapter/1#ii.

National Women’s Law Center (NWLC). (2020). The Wage Gap for mothers by race, state by state. Washington DC. Online resource document. Retrieved December 26, 2020 from https://nwlc.org/resources/the-wage-gap-for-mothers-state-by-state-2017/.

Orloff, A. S. (2002) Explaining US welfare reform: Power, gender, race and the US policy legacy. Critical Social Policy. https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183020220010801.

O’Connell, R., Owen, C., Padley, M., Simon, A., & Brannen, J. (2019). Which types of family are at risk of food poverty in the UK? A relative deprivation approach. Social Policy & Society, 18(1), 1–18.

O’Hare, W., Mather, M., & Dupuis, G. (2012). Analyzing state differences in child well-being. New York: Foundation for Child Development. Retrieved September 2020 from https://www.fcd-us.org/analyzing-state-differences-in-child-well-being/.

Parolin, Z. (2019). Temporary assistance for needy families and the Black-White child poverty gap in the United States. Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz025.

Parolin, Z. & Wimer, C. (2020). Forecasting estimates of poverty during the COVID-19 crisis. Poverty and Social Policy Brief, 4(8). New York: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

Parolin, Z., Curran, M. A., & Wimer, C. (2020). The CARES Act and Poverty in the COVID-19 crisis: Promises and pitfalls of the recovery rebates and expanded unemployment benefits. New York: Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University.

Paul, M., Zaw, K., Hamilton, D., & Darity Jr., W. (2018). Returns in the labor market: A nuanced view of penalties at the intersection of race and gender. Working paper series. Washington DC: Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Pew Research Center (2012) What census calls us: A historical timeline. Washington DC. https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/whatcensus-calls-us/. Accessed 6 Feb 2021.

Powell, B., Werum, R., & Steelman, L. C. (2004). Macro causes, micro effects: Linking public policy, family structure, and educational outcomes. In D. Conley & K. Albright (Eds.), After the bell—Family background, public policy, and educational success (pp. 111–144). New York: Routledge.

Preston, S. (1976). Family sizes of children and family sizes of women. Demography, 13(1), 105–114.

Price, G.N., Darity, W., Sharpe, R.V. (2020). Did North Carolina economically breed-out Blacks during its historical eugenic sterilization campaign? American Review of Political Economy. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.38024/arpe.pds.6.28.201.

Raine, S. P. (2012). Federal sterilization policy: Unintended consequences. Virtual Mentor, 14(2), 152–157.

Ross Phillips, K. (2001). Who knows about the earned income tax credit, assessing the New Federalism Series B, No. B-27 (January). Washington DC: The Urban Institute. Retrieved December 21, 2020 from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/61066/310035-Who-Knows-about-the-Earned-Income-Tax-Credit-.PDF.

Shaefer, H. L., Collyer, S., Duncan, G., Edin, K., Garfinkel, I., Harris, D., et al. (2018). A universal child allowance: A plan to reduce poverty and income instability among children in the United States. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 4(2), 22–42.

Sherman, A. & Mitchell, T. (2017). Economic security programs help low-income children succeed over long term, many studies find. Washington DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved December 21, 2020 from https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/economic-security-programs-help-low-income-children-succeed-over .

Shkolnikov, V. M., Andreev, E. M., Houle, R., & Vaupel, J. W. (2007). The concentration of reproduction in cohorts of women in Europe and the United States. Population & Development Review, 33(1), 67–99.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). The incomes of families with children: A cross-national comparison. Journal of European Social Policy, 17(4), 299–318.

Thomhave, K. (2018). Battle over TANF Family Cap Intensifies. Spotlight on Poverty. Retrieved December 9, 2020 from https://spotlightonpoverty.org/spotlight-exclusives/battle-over-tanf-family-cap-intensifies/.

Thomson, D., Gennetian, L.A., Chen, Y., Barnett, H., Carter, M., & Deambrosi, S. (2020). State Policy and Practice Related to Earned Income Tax Credits May Affect Receipt among Hispanic Families with Children. Washington DC: Child Trends. Retrieved December 21, 2020 from https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/EITCPolicy_ChildTrends_November2020.pdf.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in U.S. City Average [CPIAUCSL]. retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Retrieved September 17, 2020 from https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CPIAUCSL.

Willitts, M., & Swales, K. (2003). Characteristics of large families. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

Wimer, C., Fox, L., Garfinkel, I., Kaushal, N., & Waldfogel, J. (2016). Progress on poverty? New estimates of historical trends using an anchored supplemental poverty measure. Demography, 53(4), 1207–1218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0485-7.

Zelenak, L. (2004). Redesigning the earned income tax credit as a family-size adjustment to the minimum wage. Tax Law Review, 57, 301–353.

Funding

Not applicable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Curran, M.A. The Efficacy of Cash Supports for Children by Race and Family Size: Understanding Disparities and Opportunities for Equity. Race Soc Probl 13, 34–48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09315-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09315-6