Abstract

There is continuing debate on how low China’s fertility has reached and whether China has fallen into the “low fertility trap”. This paper addresses this debate by revisiting the trends in fertility preferences in the past decades in China based on a meta review. Moreover, the analysis contrasts distinct measurements of fertility preferences to capture different aspects of reproductive decision-making. This papers reviews 152 studies resulting in 137 estimates for the mean of preferred number of children, 104 estimates for the proportions of different numbers of children preferred and 66 estimates for the second-child preferences. We found that after the long-time decline of fertility preferences in the last century, the average family size remained at a low level but started to increase slowly since 2001. This upturn was observed for all three types of measurements of fertility preferences: ideal, desired, and planned family size. The results also indicate a strong two-child preference (more than 50% of respondents) in China, although 30% of people prefer one child and only a small fraction indicating an ideal family size for three or more children. Results on people’s preference for a second child were less consistent. We concluded that fertility is unlikely to increase rapidly in China even when the government adopts more relaxed family planning policy. Because the upward trend in fertility preferences was very minimal and the economic constraints will prevent many people to realise their preferences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The recent change in 2021 in China’s family planning policies that allows three children per family demonstrates a rising concern by the government about low fertility levels and an ambition to increase it. China’s fertility levels are low, but exactly how low the fertility level has been in the last two decades is a matter of much debate in demographic research. Total fertility rates (TFR) are reported as 1.19 in the census of 2010 and 1.3 in the census of 2020 (Yang et al., 2022; Gu & Guo, 2014), while TFRs of around 1.6–1.7 have been reported on the basis of education enrolment data or some national surveys (Chen, 2016; Chen & Duan, 2019; Zhai et al., 2015b).

This lack of unanimity about fertility has led to various discussions (Jin, 2014; Wu, 2016, 2019; Yang, 2012) including whether China would fall (or has already fallen) into the “low fertility trap” (Lutz et al., 2006). There are those who argue that China is standing at the edge of the trap (Liu & Chen, 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Wu, 2016, 2019) or has already fallen into the trap (Mu, 2013, 2014; Yang, 2012), because China’s total fertility rate has reached very low levels of fertility (e.g., below 1.5, a specific watershed point of the trap observed by Mcdonald (2008)) and because preferences for children are also low (Basten & Jiang, 2015; Hesketh et al., 2005; Poston & Gu, 1987; Wu, 2019). In contrast, others argue that China is not (yet) at risk of falling into the low fertility trap (Chen & Zhai, 2016; Chen & Duan, 2019; Jin, 2014; Yang et al., 2008; Zhai et al., 2015a), because they believe that China’s fertility rate never reached a very low level, and that there still exists a strong preference for two children.

In both arguments, preferences feature heavily. Similarly, in the theory of “low fertility trap”, declining fertility preference is an important mechanism to explain the lasting low fertility in Europe (Lutz et al., 2006). A key question is therefore how high or low recent fertility preferences in China are, and what has been the trend in these preferences in the past decades. Ideally, the way of establishing this would be to carry out an original analysis of a large number of surveys in order to chart the trend in fertility preferences, for instance as Sobotka and Beaujouan (2014) have done for Europe. Since most surveys in China are not in the public domain and not accessible, an alternative way is to rely on secondary data. A handful of studies have already been done using such an approach in China in different time periods: 1980–1985 (Whyte & Gu, 1987), 1979–1999 (Feng & Zhang, 2002), 2000–2008 (Yao et al., 2010); 1979–2009 (Basten & Gu, 2013) and 1980–2011 (Hou, 2015). Overall, these studies conclude that there has been a decline in fertility preferences from 1979 to 2000, followed by a levelling-off from 2000 onwards. However, it is unclear whether this levelling-off trend of low fertility preferences in the 2000s has continued in more recent years. This is a particularly relevant question considering the relaxation of the family planning policies and the continued rapid cultural and economic changes of the past two decades.

This paper revisits the trends in fertility preferences in the past decades in China. Moreover, the analysis contrasts distinct measurements of fertility preferences to capture different aspects of reproductive decision-making.

Background: fertility preferences in China

The average ideal family size in China has systematically declined from around 2.1 in 1980s to 1.9 in 1990s, and 1.7 in the 2000s according to previous research (Feng, 2017; Feng & Zhang, 2002; Hou, 2015). This steady decline in fertility preferences is typically attributed to the combined effects of government policies in the past, together with the rapid social-economic development in China (Attané & Barbieri, 2009; Basten & Jiang, 2015; Chen, 2005; Gu, 1987; Li, 2017a, 2017b).

Family planning policy in China is often translated as the “one child policy”. However, these policies are much more complicated than its infamous English name and have played different roles on fertility in different times. This policy was first introduced in the 1970s, beginning with the “wan, xi, shao” slogan that encouraged late marriage and childbearing, fewer births and longer birth spacing. Later, in 1979, a strict policy that became known as the “one child policy” was implemented. Soon this policy was changed, and in 1984 rural families were allowed to have a second child if their first child was a daughter or if both partners in a couple were the only child in their original families (Attané, 2002; Poston & Gu, 1987). In 2002, urban families could also have a second child if both partners in a couple were both from a one-child family. In 2013, there was a further relaxation of policies in that all families could have a second child if one of the partners in the couple was from a one-child family (Xin Hua She, 2015). In 2016, the restrictions to have only one child were completely lifted and all families could have two children. In 2021, a new policy announced that all families can have three children and the government will introduce related welfare measures to support families (Xin Hua She 2021). Meanwhile, different ethnic groups also had different regulations and some groups were allowed to have more children (Attané, 2002; Wang, 2019). How the Chinese people responded to these changes in family policies is a matter of debate, and many potential reasons can be given for why these policies would increase preferred family size but also for why they would not.

Reasons why Chinese fertility preferences might increase

According to some, the changes in policies are believed to have had a strong influence on fertility preferences as the observed decline in fertility preferences was the result of policy restrictions, and, once these policies are relaxed, fertility preferences would rise to higher levels (Jin, 2014; Tao & Yang, 2011). Three supporting arguments are typically put forward. Firstly, the strong son preference and two-child norm in China are a strong motivation for having more children (Jin, 2014; Shi, 2012). The son preference originates from patriarchal culture in which only sons can inherit family resources. This history also explains why couples are allowed to have a second child if their first child was a girl in rural areas even in times of strict family planning policies (Feng & Zhang, 2002; Ma et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2010). The importance of the son can prompt people to have further children until there is a son in the family (Fei, 1948). The two-child preference is strong in China, similar to that observed in Europe (Sobotka & Beaujouan, 2014), and many Chinese individuals think the ideal family is to have one son and one daughter (Feng & Zhang, 2002; Zheng, 2014; Zhuang et al., 2014). Moreover, frequent reasons for having or preferring a second child in China is to provide a companion for the first child in order to increase the wellbeing of the children and a fear of losing the only child (Zheng et al., 2009).

A second reason why fertility preferences would increase, is that close family bonds and relaxed policies make it possible for grandparents who want to have grandchildren to exert their influence on their children by pushing them to get married and to have children. It is an interesting social phenomenon that older parents are more anxious than their children themselves about finding a partner and starting a new generation (Liu & Xu, 2006; Zheng et al., 2009). Many couples even decide to have a child or a second one just because of their parents’ strong desire to have (more) grandchildren (Zheng, 2014). Grandparental support would further reduce the burden of childcare that could increase motivation to have a/another child (Li & Feng, 2016).

A third reason is that the pronatalist family policies aim to create a more friendly environment that supports families to have more children. The government has realized the difficulties of raising children for families and is planning facilities to reduce the burden of families such as providing better healthcare for mothers, more easily accessible and affordable childcare, and reducing the price of education (Xin Hua She, 2021). Moreover, the government tries to establish new values concerning marriage and fertility: having more children is a contribution to society instead of a burden as previous family planning policies implied (Mu, 2021).

Reasons why Chinese fertility preferences might not increase

In contrast to the above outlined reasons for why fertility might increase after the relaxation of family policies, others have stressed that social-economic development plays a more important role in shaping preferences than these policies (Basten & Jiang, 2015; Li, 2017a, 2017b; Zhai et al., 2015a; Zheng, 2014). They argue that rapid economic growth and urbanization have changed perceived value of children among Chinese people, leading to more people favouring smaller family size (Zhuang et al., 2014). This implies that fertility preferences are unlikely to increase in the short-term irrespective of changes in family planning policies (Feng, 2017; Li, 2017a, 2017b; G. Wang et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2010).

Three reasons are often proposed to support the argument that the fertility preferences would remain at a low level or even decrease. First, there is the argument that the mechanism of “sociological reasoning” that is highlighted by the “low fertility trap” theory (Lutz et al., 2006) will also hold for China. According to this mechanism, “The fewer the children belonging to the environment that young people experience, the lower the number of children that will be part of their normative system in terms of what is a desirable life” (Lutz et al., 2006, p. 176). The current small core family structure thus reshapes ideal family sizes of young generations of Chinese as they were raised in small families with few or no siblings (Feng & Zhang, 2002; Zheng, 2014). Further, the widespread existence of small families may shape preferences of ideal family size within a population (Zhao et al., 2017). Thus, younger generations may have preferences for small families because of socialization and social learning despite relaxation or ending of policies limiting births.

A second reason why fertility preferences might remain low is the rising financial and opportunity costs of raising a child in China (Feng, 2017; Li, 2017a, 2017b; W. Liu & Xu, 2006; Zheng et al., 2009). There is limited financial support from the government for families, meaning that the financial burden falls mainly on the families themselves (Wang & Liu, 2017). Hesitations to have more children are because many families believe they cannot afford to raise more children due to the high housing prices and costs for education from kindergarten to university (Wang & Liu, 2017; Zheng et al., 2009). The high costs of raising children are not only financial. For instance, there are further worries that having more children decrease the quality of living for the family (Liu & Xu, 2006). Moreover, parents often feel anxious about the future of their children, particularly when they cannot provide the best resources (e.g. education opportunities) for their children as there is stark competition to enrol in top universities (Anderson et al., 2013). Parents are further required (normatively) to spend more time to accompany and educate their children nowadays, which comes at a cost of their working and leisure time (Basten & Jiang, 2015; Li, 2017a, 2017b).This cost is especially high for women, who suffer from motherhood penalties in the labour market and who are typically responsible for the heavy burden of housework and care within households (Yang, 2017).

A third reason for why fertility preferences might remain low is that the perceived value of children has changed due to the establishment of a pension system in China that has shifted care for elder people from family to society (Kang & Sun, 2018).Thus, the motivation for children as a source of care in later life decreased. In other words, the “value” of children has similarly shifted from a “security” utility (guarantee of care for later life) towards a “consuming” utility (enjoyment and fulfilment to raise a child) (Liu, 2017). The (perceived) high costs of having (multiple) children combined with the perceived low “benefits” (Zheng et al., 2009), is argued to have reshaped fertility preferences to very low levels in China.

This study

It is still unclear whether fertility preferences have kept at a stable low level since the 2000s or whether these preferences have increased in recent years due to the relaxation of family planning policies. Recent studies have yielded mixed results. According to Hou (2015), the ideal family size has stabilized at 1.6–1.7 on average in the 2000s based on a number of surveys from 2001 to 2011. Two national surveys by the China Population and Development Research Center (CPDRC) on fertility preference in 2001 and 2006 concluded that the ideal family size is respectively 1.78 and 1.73 on average (Feng, 2017). In 2013, CPDRC conducted a new survey and reported an even higher ideal family size of 1.93 (Zhuang et al., 2014).

In this paper, we revisit this topic by carrying out a meta-regression analysis of 152 studies from a total of 113 surveys. Moreover, we framed our analysis with respect to the two contrasting expectations regarding trends in fertility preferences: one that assumes that it remained low or has decreased, and the other assumes that it has been increasing in the last two decades.

This paper will also fill the gap in literature by making explicit the distinctions between different fertility measurements (including fertility desires, preferences, and plans). Previous literature focused mostly on the average ideal family size (Basten & Gu, 2013; Feng & Zhang, 2002; Hou, 2015; Whyte & Gu, 1987; Yao et al., 2010) and have not included the distinction between desires and intentions (for a notable exception see Feng (2017), although this work does not show the trends of preferences). Furthermore, we show trends in parity-specific preferences to better understand fertility preference in China. We further attempted to make our data collection procedure as transparent as possible and provide all our data as an online supplement.

Data and method

The measurements of fertility preferences

Before moving on to our analyses to address how fertility preferences have developed over time, it is important to note that fertility preferences are measured in many ways in surveys. It is essential to distinguish these different measurements of fertility preferences because whether fertility preferences are changing over time may depend on the measurement under study. For example, low levels of planned family size that are much closer to actual fertility might be used as evidence to argue that China has a high risk to fall into the “low fertility trap”. This conclusion will change if there is a very high-level ideal family size.

Moreover, the Chinese literature on fertility preferences is different from the Western demographic literature in their focus. Fertility preferences in the western demographic literature is a generic term encompassing different points of fertility-decision making i.e., fertility ideals, fertility desires, and fertility intentions. In contrast, in Chinese demography, the word “fertility desires” is the term most used (Feng, 2017). It is often broken down into three dimensions: 1) the quantity of children, 2) the gender of the children, and 3) the desired timing of fertility behaviour (Gu, 2011). Note that the term “生意意愿” translated as “fertility desires” in English can be a specific concept that means desired number of children, but it is also a collective noun that presents all different concepts of fertility preferences in Chinese literature. We only discuss the first quantitative dimension of Chinese "fertility desires" in this paper.

According to the questions on fertility preferences asked in surveys, we regrouped the different measurements under three headings: ideal, desired, and planned. The major difference between fertility “ideals” and “desires” is the consideration of realistic barriers in the latter concept. “Fertility plans” include even more realistic barriers and especially the feasibility in the near future to realize the preferences. Plans are closely related to intentions to have children after considering all possible barriers.

Research on fertility preferences in China has further differed from the Western demographic literature in two ways. First, because of family restriction policies in China, researchers have found novels ways to address fertility preferences in China. In particular, respondents are often asked about their ideal/desires/planned fertility while they had to imagine that there were no restrictions in place. Additionally, many surveys in China focus on whether people want to or plan to have a second child, as previous studies show that most people prefer one or two children instead of a larger family size since the 1990s (Feng, 2017; Hou, 2015). Therefore, the preference to have a second child is an alternative indicator to measure how preferences have changed in twenty-first century China and can provide evidence towards the idea that preferences have been suppressed during the period of policy restrictions previously.

Table 1 summarises the different concepts and their measurements with respect to fertility preferences. The full list of concepts and measurements in the Chinese literature and their translations in English can be found in the supplementary document S1.

Search and resulting database

In order to capture all Chinese studies that reported on fertility preferences, we used the concept and measurements outlined in Table 1 as keywords to search for papers in the China National Knowledge Infrastructure database (CNKI), the largest digital publication resource in China. Similar to Feng (2017), we also included the term “survey” in our search term, as we need the information on the survey for the empirical analyses. The search syntax is:

Survey AND (fertility desire OR fertility preference OR fertility expectation OR fertility intention OR fertility decision OR Ideal number of children OR ideal family size OR desired number of children OR expected number of children OR planned number of children) in Chinese (see supplementary document S2 for Chinese translation).

We restricted the search to papers that are included in core journal publication database in CNKI to guarantee the quality of data. This resulted in 261 publications (date of search until: 11-06-2018). Full texts of all these papers were screened, and publications that did not meet our three criteria listed below were excluded from our analysis sample. These criteria were: 1. the paper must involve quantitative research that contains detailed information on the survey(s) used; 2. the sample size of the study is over 500; and 3. The population under study should not be too specific (e.g., only students or high-educated women). We kept all papers identified by CNKI and that met previous criteria. We assumed them to be of decent quality given that they came from core journals, and we made no further assessments of quality. This led to a final sample of 152 publications that we used for our analyses. The detailed steps of the search strategy and the consideration of selection of papers can be viewed in supplementary document S2.

Indicators captured

We subsequently extracted the following information for each publication: (1) which survey was used; (2) what exact wording or question(s) was (were) used to measure fertility preferences; (3) the year of the survey; (4) geographic region (including the size of the representative area and the name of the region); (5) sample size of the survey and the sample used for analysis; (6) the estimates fertility preferences by different measurements. We also recorded the information of the sample characteristics for each study including age-groups, gender, marital status, having children or not, rural or urban residence of the sample (See Table 2 for the variables in the dataset, and explanation of the coding in supplement S7).

For the estimates of fertility preferences, three indicators were recorded: (1) the average number of children preferred, (2) the proportion of people preferring 0, 1, 2, 3 and more than 3 children, and (3) The proportion of people preferring a second child.

For our first indicator of fertility preferences, if an estimate on the average number of children was missing, but the study provided the proportions of people preferring 0, 1, 2, 3, or more than 3 + children, we calculated an average based on these estimates (there are 55 cases) for more information see supplemental material S3). The proportion of people preferring different parities (indicator two) is based on the question of how many children were preferred in total (see also indicator one). For the proportions of different numbers of children preferred, we excluded estimates that did not specifically refer to the proportion that prefers to have two children. In such cases, estimates combined the proportions of people that prefer two children and more than two children, which make them unsuitable for comparison to the proportions of people that prefers zero, one, two, or three and more children.

The third indicator concerned the people preferring a second child which was based on questions that asked specifically about second-child desires or plans. Thus, this indicator is different from the proportion of people that plans or desires a family size of two from our second indicator. Another difference with indicator two is that with second-child preferences only desires or plans are asked about, and not ideals. In addition to the proportion of people who answered whether they wanted/planned a second child or not, for the second-child preferences there were 29 studies that also provided the proportion of people who are uncertain about their preference to have a second child (i.e., the proportion of respondents that gave answers like “uncertain” or “I don’t know” in response to the question on preferences for a second child). Two studies considered preferences for the timing of a second child (i.e., preferred within 6 months or 12 months). This is rather different from the other two-child preferences. Excluding these estimates from our analyses led to nearly identical results, so we kept them in the analysis.

Where possible, we used the original questionnaires to determine how fertility preferences were measured. Firstly, the original Chinese questions on fertility preferences in the survey were recorded. Subsequently, these questions were divided into different measurements and translated into English (see supplementary document S4). We collapsed the different types of measurement into six categories: (1) ideal family size, (2) ideal family size without consideration of policy restrictions, (3) desired family size, (4) desired family size without consideration of policy restrictions, (5) planned family size, and (6) planned family size without consideration of policy restrictions. For the preference to have a second child or not, we collapsed four types of measurements according to the questions asked in the survey: (1) second-child desires, (2) second-child desires without consideration of policy restrictions, (3) second-child plans and (4) second-child plans without consideration of policy restrictions.

If a publication did not provide the questions of the survey, then we used the description of the measurements in the paper (N = 28 papers). In 14 papers, measurements that were used were different from the above classifications. We excluded these publications from our analysis (for further details see supplementary document S5). If one publication reported several estimates for different years, or estimates for different measurements, all estimates were recorded. In other words, our unit of analysis is the estimate of fertility preference rather than the study. It also indicates that many surveys have more than one estimate. This resulted in 152 studies producing 196 rows of data including 137 estimates for the mean of preferred number of children,Footnote 1 104 estimates for the proportions of different numbers of children preferred and 66 estimates for the second-child preferences. Our main purpose is to test whether the trend in fertility preferences has remained at a low level over time or whether it has increased since 2001 in this paper. So, we only use estimates from year 2001 for our meta-analysis. This leads to 124 estimates for the mean of preferred number of children (there is only one estimate of average planned family size, which we exclude from analyses) and 63 estimates for the second-child preferences in the analysis.

Previous work discusses to what extent heterogeneity of fertility preferences can be explained by sample characteristics, and showed that sample demographics, sample region, and the measurement of fertility preferences together accounted for nearly 50% of the variation in average preferred fertility (Lu et al., 2021). This paper focusses on the historical trend of fertility preferences in China, controlling for sample characteristics. An important point for this study is that the variation in the ways second-child preferences were assessed (our third indicator) is larger compared to other outcome measures.

Methods of analysis

We use a mixed-effect meta regression that allows us to test whether there is a difference across time as well as across different measurements while it also allows a random-effect model within such groups (Harrer et al., 2019). A random effect here is necessary because the between-study heterogeneity is large. A mixed-effect model that includes random effects uses information from both within and between variance of studies. Especially for studies that used samples with different characteristics, a random effect is desired in order to generalize this meta-analysis to a universal population instead of the samples included in these 152 studies.

A meta-regression model needs the inverse variance of each estimate as weights (Schwarzer et al., 2015). The formula below is to calculate the inverse variance for average preferred family size of each estimate:

w: Inverse variance for each estimate, SE: Standard error for each estimate, SD: Standard deviation for each estimate, n: Sample size for each estimate.

Unfortunately, a standard deviation (SD) was available for only 18 mean estimates (out of 124) since 2001. We use the proportions of different numbers of children preferred reported in these studies to calculate the SDs (85 estimates), see supplemental material S3. We later imputed the average of all SDs to replace the remaining unknown (21 estimates). Different from the averages, we calculated the inverse variance of proportions who prefer the second child using the proportions and the sample size to calculate standard error for proportions. The formula is:

SE: Standard error for each estimate, p: The proportion of people who prefer to have a second child for each estimate, n: Sample size for each estimate.

As the proportions of each preferred number of children are not independent from each other, we could not apply a meta-analysis for this indicator. Instead, we used descriptive information to weigh in on our expectations. All analyses were done in R (Harrer et al., 2019), and we used the R package ‘metafor’ (Viechtbauer, 2010) for meta-analyses. We use alpha = 0.05 as a threshold for significance.

For both the average preferred number of children and whether to have a second child, we first fitted a model with only the linear term of year, after which we fitted a model adding a quadratic term of year and compared them by tau^2 (the amount of residual variability) and R square (the amount of variability explained by predictors) to examine whether it improved the model fit. We used a linear model (function “rma”, measure = “GEN” with method of Maximum Likelihood) for the averages, and a logistic model (function “rma.glmm”, measure = ”PLO” to use the logit transformed proportions with method of Maximum Likelihood) for proportions. We subsequently checked whether trends varied across different fertility measurements using interaction terms between year and type of measurement. We did not add interactions to compare trends of each measurement for second-child preferences as there are only 63 estimates, and there were no or few estimates in several years (e.g., 2003–2005). To reduce variance in estimates between studies and get a better estimate of the effect of time, we included the following sample/study characteristics as control variables: age, gender, marital status, urban/rural, region (see supplemental material S6 and S7).

Robustness check

There are many surveys that have more than one estimate in our analysis, thus as a robustness check we include “survey” as a higher level group effect in a three-level meta-regression model to control for this nested effect. Results were very similar (see supplemental material S15).

There was substantial variation in all our estimates of fertility preferences. This is due to a combination of ‘true’ variation due to different sample characteristics, sampling variation, and measurement error. To have more confidence in the results we present, we perform many robustness checks. Our strategy was, first, to redo all analyses while only including the middle 90% of the datapoints (excluding the bottom 5% and top 5% of estimates). A second robustness check was to include only national surveys (see supplemental S15). National surveys have the advantage of being large, and not focussing on any particular groups (e.g., only women), but the disadvantage is that there are few of them.

A third way in which we provided robustness checks, was to deal with time differently Although we included all surveys as identified by our search, unfortunately for some years there were few or even no datapoints/surveys (see the distribution of data points by year and the different measurements across each year in supplement S10). A consequence of this was that there was substantial uncertainty around the estimates of our statistical analyses. Thus, we did robustness checks dealing with different time-periods. We categorised time in three periods (2001–2006, 2007–2012, 2013–2018) and two periods (2001–2010, 2011–2018) for the analyses on average fertility preferences. We used the same method, mix-effect meta-regression models, to test the trends within these 6-year periods (e.g., whether there is a significant effect of year within a particular period). Similarly, we checked the trends of average fertility within the period of 2001–2010 and 2011–2018. For the second-child desires, we ran meta-regressions using the period from 2006 to 2011 only (because there were a series of family policy changes since 2011 and there were few datapoints available before 2006). Results of all robustness checks can be found in supplemental table S15, and we will comment on these results below.

Results

Descriptive findings

For average preferred family size, the concept of ideal number of children is used in more than half of studies (of which 22% asked the ideal family size when not considering policy restrictions), about a third of studies used desired number of children (of which 47% asked the desired family size when not considering policy restrictions), whereas the planned number of children was used in fewer than 10% of studies (with only one survey reporting on the planned number of children without considering policy restrictions). For second-child preferences, 32% of estimates were based on the question on desires for a second child, 24% were based on a question of whether respondents desired to have a second child if there were no policy restrictions), 35% involved the plans for a second child, and 9% asking about plans without considering policy restrictions) (see also Table 2).

From all estimates of average family size, there is a decline in preferences from 1986 to 2000 (see Fig. 1), which is consistent with previous literature (Feng & Zhang, 2002; Hou, 2015; Yao et al., 2010). But this trend seems to stop near the 2000s, after which the variance in the average preferences is large and a clear trend of time cannot be observed from this descriptive figure.

Table 3 shows that, on average, the hypothesized ideal and desired family size in the case that no policy restrictions are considered are higher than those when policy restrictions are considered. Average ideal family size with or without policy restrictions are similar, and they are higher than planned and desired family size. When reviewing the averages per six years, we found that the average preferred number of children was highest in most recent times (2013–2018) compared to earlier periods (2007–2012 and 2001–2006). Average ideal family size was also higher than planned and desired family size in these six-year periods.

From the proportions of different number of children preferred since 2001, we found that most people in China report a desired family size of one child (average across studies is 37%) or two children (54%). The average proportion of people who think the ideal family size across studies is one child was 27%, while the proportion for two children was 65%. People seldom choose to have no children or to have three or more children according to the distribution of proportions on different family sizes people preferred (see Table 4, 5). The proportion of people that preferred two children is higher than the proportion that prefers one child on average. When reviewing the average proportions per six years, we found that in all measurements, the average proportions for no children and three or more children are very low in all periods (< 10%). The average proportion of people who preferred one child increased from the period of 2001–2006 to 2007–2012 but then decreased in 2013–2018; while the average proportion for the preference for two children increased over the three periods. (See the descriptive table in Table 4).

Figure 2 suggests that the preference for two children has increased in recent times, whereas the preferences for one child has decreased, and the preference for three or more than three remain steady at very low level. Specifically, the proportion of people who had an ideal family size of two children with/without considering policy restrictions increased from 0.6 in 2001 to around 0.75 in recent years on average, which means the majority of people preferred two children. Correspondingly, the proportion of people whose ideal family size is one child decrease from around 0.3 in 2001 to 0.2 in recent years. When comparing the desires for the family size, the proportions preferring two children fluctuated around 0.5, which was lower than the ideal family size, about 0.3 desired to have one child.

As most people in China prefer to have one or two children, it is insightful to examine the preferences for a second child in China in particular. This preference is important in Chinese demographic literaturethat it is often asked explicitly in many surveys. And when we compared the proportions of second-child specific question with the proportion of two-child family size preferences, we found proportions of second-child desires or plans are much lower than the two-child family preferences (see Table 5).

We can observe from Fig. 3 which show the proportions of people who either desired or planned to have a second child, that there was substantial variation in second-child preference. The proportions of people that plan to have a second child was lower than the proportion of those who desire to have a second child when comparing the measurements. There are furthermore quite some people who are uncertain about having a second child (Fig. 3), as on average 22% expressed uncertainty about having a second child among the 29 studies that allowed for these answers (e.g., allowed answers like “uncertain” or “I don’t know” in response to the question on a preference for a second child). Respondents that were given an option to express uncertainty about their fertility preferences had on average lower preferences for a second child than respondents who could not express this uncertainty (Fig. 4). Perhaps not surprisingly, the variation in preferences was larger in respondents who were not able to express uncertainty.

Results of meta-regression for average preferred family sizes

The meta regression on average preferred family size since 2001 revealed that there is a very small but increasing effect of year of 0.01 (95% confidence interval (CI) is from 0.00 to 0.02, se = 0.0053, p < 0.05), which implies a 0.01 extra preferred number of children per year (see Table 6, model 1).Footnote 2 Controlling for sample characteristics slightly increases the effect of year resulting in 0.02 extra preferred number of children per year (CI is from 0.01to 0.03, se = 0.0048, p < 0.001; the results of the full model with all control variables can be found in supplement S8).

There are differences in averages across the different measurements. The ideal number of children was 0.12 (CI is from 0.02 to 0.23, se = 0.05, p < 0.05) higher than the desired number of children on average. Considering the ideal number of children without considering policy restrictions, we found that they were 0.20 (CI = (0.07,0.33), se = 0.066, p < 0.01) higher than the desired number of children. The desired number of children without considering policy restrictions was 0.15 (CI = (0.02,0.28), se = 0.07, p < = 0.05) higher than the desired number of children. The average for the planned number of children was 0.13 lower (CI = (− 0.28,0.19), se = 0.08, p = 0.08) than the desired family size (supplement S8).

We carried out a number of additional analyses to test the robustness of the observed increase. When excluding the lowest 5% and highest 5% of the data and focussing on the middle 90%, we still find a very small but increasing trend for average number of children preferred (0.0095 increase per year, se = 0.0039, p = 0.0143) (See result in supplements S13). When restricting the sample to only national surveys or only women with children, we again observe a small increasing trend (see results in supplement S15).

When testing the trends in average preferences in different time periods for six-year period (2001–2006, 2007–2012, 2013–2018) and for longer periods (2001–2010 and 2011–2018), we consistently found positive trends, but the effects are small and not statistically significant in these periods (See results in supplement S15).

There was little evidence that the changes in preferences over time were different for our different measurements, as none of the interaction terms reached statistical significance and adding the interactions to the model only explained 1.7% more variance. The F test also showed that the interaction-terms did not improve the model significantly (see details in supplemental material S8). The steepest trend was observed in desired number of children without considering policy restrictions, and the weakest trend in the desired number of children (see Fig. 5). Thus, the evidence is consistent with a very small trend among all measurements of fertility preferences.

Meta-regression results for second-child preferences

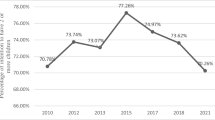

Further insight is gained by investigating specific preferences for the second child as most people prefer either one or two children in China (see Fig. 2). Indeed, in the Chinese demographic literature there is often a specific focus on the preferences for a second child. There seems to be no increasing or quadratic trend in the proportions of people that prefer to have a second child according to the meta-regression models using only year as moderators (see Table 7). When including the sample characteristics into the regression, there is a small increasing trend such that the odds of people that prefer to have a second child in one year is 1.11 times higher than the previous year (log odds ratio is 0.022, 95% confidence interval (CI) is from 0.01 to 0.003, se = 0.0071, p < 0.01; see the complete result of full model can be seen in supplement S9). We also found a quadradic trend of the second-child preferences which indicates that the proportions of people who want to or plan to have a second child increases but slows down at the end of the study period (see supplement S9). The quadratic model improves the R square by 6.7%. In conclusion then, the preferences for having a second child increases at first but then levels off (see Fig. 6).

Robustness checks showed that this trend in second-child preferences was not robust. When restricting our sample to only include the middle 90% of data (thus excluding the lowest 5% and highest 5%), we find little evidence for an increase or decrease in second-child preferences (see Supplement S14). Also, when examining the trend in the period from 2012 to 2018, we did not find any evidence for an increasing or quadratic trend (see supplement S15).

Conclusion and discussion

Our results provide a unique perspective on the historical dynamics in fertility preferences in China and indicates the possible trend of fertility preferences especially in twenty-first century. In particular, it allowed us to test two competing views regarding recent trends in fertility preferences: one according to which preferences have increased, and an opposite one claiming instead that despite these policy relaxations, fertility preferences remained low or even decreased. Based on our results, we conclude that after a long-time decline of fertility preferences in the last century, average fertility preferences remained at a low level but have started to increase slowly in the last two decades. Thus, we found more support for the first view that fertility preferences in China have increased (Jin, 2014; Tao & Yang, 2011) especially for ideal family size, and less support for those who considered decreasing trends (Z. Wang & Liu, 2017; Zheng et al., 2009). We observed rather large differences between the different fertility measurements but there is little evidence showing that these measurements change differently across time.

We will discuss each type of fertility preference and how they fit with earlier expectations about the trend of fertility preferences in China. Data on average ideal family size and data on proportions of people preferring particular family sizes support the view that fertility preferences have increased up to two children on average in twenty-first century. The ideal family size has increased slowly from 1.87 to 2.07 on average from 2001 to 2018 in our meta-analysis. More than half of people consider two children as their ideal family size, while fewer than 10% people take three or more as ideal number of children. The ideal family size rose to 2 children in the last two decades, which indicates that people prefer to have two children on average.

This argument is further supported by the finding that the ideal family size without considering policy restrictions and desired family size without considering policy restrictions have similar trends as ideal family size since 2001. Without policy restrictions, ideal family size is estimated to reach to two children around 2013 based on our meta-regression analysis. The finding that ideal family size without considering policy restrictions and desired family size without considering policy restrictions are at a similar level as ideal family size, reinforces the use of ideal family size as a measure in which respondents do not consider barriers and restrictions to fertility decision making. Thus, both ideal family size, and ideal and desired family size without considering policy restrictions can be seen as the same type of measurement: an unconstrained ideal fertility. And these fertility ideals have been close to two children from 2010.

The finding that fertility ideals are close to two children in China suggests that preferences for a family size of two have persisted through periods when family planning policy restricted the expression of actual fertility ideals. This finding, together with the observation that more than half of Chinese continue to prefer to have two children, can be considered as evidence for a two-child norm. However, by referring to this pattern as a norm, one might easily forget that there is also a substantial fraction of people that preferred only one child (around 32% on average), and that many people were uncertain about their preference to have a second child (22%).

Fertility desires take into account barriers in life in realizing fertility ideals, e.g., the financial burden and work-life balance difficulties (Li, 2017a, 2017b; Wang & Liu, 2017; Yang, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017), and it is thus no surprise that we find lower averages for desired than for ideal family size. Nonetheless, we also observed an increasing trend in fertility desires, as they rose from around 1.6 to 1.9 on average from 2001 to 2018. Planned family size, arguably the measure that is closest to actual fertility, is even lower than ideal and desired family size, further corroborating the idea that plans take into account barriers to having children. Yet, also the planned number of children increased from around 1.3–1.6 between 2001 and 2018. The averages of planned number of children and desired number of children reached similar levels in more recent years. This may relate to the relaxation of the two-child policy since 2016, with the consequence that people may have been less hesitant in expressing their true preferences. To sum up, fertility desires and plans, both of which consider barriers in fertility decision-making, are lower than fertility ideals. Although there is a slight increase in the last two decades in these two measures, they are both still lower than two children on average.

As most people in China prefer to have one or two children, a preference for a second child may shed further light on changing preferences. The second-child preference is so important in Chinese demographic literature, at least partly due to China’s history family policies, that respondents are often asked explicitly about their preference for a second child. We find only limited support for an increasing trend when examining second-child preferences. Some of our analyses suggest that the proportions of people who plan for and desire to have a second child have increased in the first 15 years in the twenty-first century, after which the trend levelled off. Speculatively, these changes in second-child preferences can be a consequence of changes in family planning policy. Before 2016, not every family was allowed to have two children, and the preference for a second child may have manifested in people who were not allowed to have a second child and wanted the right to have one. Once family planning policies were relaxed, and everyone was allowed to have two children, these people may have realized better the difficulty of raising two children and the high costs involved child (Zheng et al., 2014; Song, 2016).

It is important to note, however, that the trend in second-child preferences was not apparent in several robustness checks. One reason why the findings on second-child preferences are less clear, may be the various ways in which people were asked about their second-child preference. Also, the large proportion of people who were uncertain about their second-child preference, may have contributed to the uncertainty. A safer conclusion may be that there certainly is no evidence for a decrease in second-child desires or plans in the last decades.

There are certainly limitations in this paper. Regarding the data selection: even though we had a substantial number of estimates for our analyses, we had only few datapoints in recent years. Thus, preferences for these later years are estimated with less certainty, which is unfortunate, because it also means we can be less certain about trends in the short-term future. There is also large heterogeneity in sample characteristics, and our meta-regression was probably not able to account entirely for this heterogeneity. Restricting the sample of estimates to a particular subgroup (e.g., only men) was often not possible due to limited sample size.

So, does China have a high risk to fall into the “low fertility trap” implying that fertility rates are unlikely to rebound from the perspective of fertility preferences? This is a difficult question to answer given the limitations of our data and the uncertainty surrounding our statistical estimates. We found some support for an increasing trend in ideal family size and a strong preference for two children. However, desired and planned family size, measures which take into account barriers to realizing fertility, are still low. Moreover, few people want more than two children in recent decades and substantial numbers of people are uncertain about a second child. Thus, from this perspective, it is unlikely that China’s fertility increases rapidly in response to the recent three-child policy. Fertility will likely stagnate or even decrease if such policies are not also supplemented by policies that reduce the burden of raising children in contemporary China as other researchers argued (Wu, 2019; Yang, 2017).

Data availability

The detailed search and selection process of the meta review and the data can be found in DataverseNL (https://doi.org/10.34894/E1TA3X) once this paper get published.

Notes

One extremely low estimate from an internet survey in 2016 is excluded from analysis. This internet survey had serious issues of representativeness and was not comparable to estimates from surveys based on face-to-face or telephone interviews.

If the quadratic term of regression is not statistically significant and the effect size is small (effect size is around 0.001, p > 0.1, in both models for average preferred family size. The CI is (− 0.0012, 0.0034) in the model with only year and quadratic term of year, CI is (− 0.0008, 0.0032) in the full model, so we only show the result of linear term in this paper.

References

Anderson, T., & Kohler, H. P. (2013). Education fever and the East Asian fertility puzzle: A case study of low fertility in South Korea. Asian population studies, 9(2), 196–215

Attané, I. (2002). China’s family planning policy: An overview of its past and future. Studies in Family Planning, 33(1), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2002.00103.x

Attané, I., & Barbieri, M. (2009). The Demography of East and Southeast Asia from the 1950s to the 2000s A Summary of Changes and a Statistical Assessment. Population, 64(1), 9–146. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.901.0009

Basten, S., & Gu, B. (2013). Childbearing preferences, reform of family planning restrictions and the Low Fertility Trap in China. August, pp. 1–43. https://www.spi.ox.ac.uk/fileadmin/documents/PDF/WP_61_Childbearing_preferences.pdf.

Basten, S., & Jiang, Q. (2015). Fertility in China: An uncertain future. Population Studies, 69, S97–S105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2014.982898

Cai, Y. (2012). China’s demographic prospects: A UN perspective. China’s Demographic Prospects, 1, 73–95.

Chen, J., & Zhai, Z. (2016). The dynamics of international fertility and the analysis of its causes since 20th century. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 12–25.

Chen, W. (2005). The dynamic relationship between “development-family plannin-fertility rate”: Review of the provincial data. Population Research, 29(1), 2–10.

Chen, W. (2016). Estimates of fertility level in China for the recent years. Academia Bimestrie, 01, 67–75.

Chen, W., & Duan, Y. (2019). The fertility level and its trend in the last 10 years in China. Population Research, 43(1), 3–17.

Fei, X. (1910–2005). (1948). From the soil—The foundations of Chinese society. Bei jing shi dai hua wen shu ju.

Feng, X. (2017). The contemporary Chinese fertility preferences: What do we actually know? Social Sciences in China, 8, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.13644/j.cnki.cn31-1112.2017.08.006

Feng, X., & Zhang, Q. (2002). Study on 20-year dynamics of fertility preferences of Chinese in urban and rural areas. Market and Demographic Analysis, 8(5), 21–31.

Gu, B. (1987). The effect of social economic development and family planning policy on decreased fertility rate in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 2–11.

Gu, B. (2011). Fertility preference, fertility behaviours and fertility level. Population Research, 35(2), 10–14. https://doi.org/10.16194/j.cnki.31-1059/g4.2011.07.016

Guo, Z., & Gu, B. (2014). China’s Low Fertility: Evidence from the 2010 Census. pp. 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8987-5_2.

Guo, Z. (2011). The results from 6th Census show there are serious mistakes in the previous estimates and projections of population. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 6, 2–13.

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T.A, & Ebert, D. D. (2019). Doing meta-analysis in R: A hands-on guide. https://bookdown.org/MathiasHarrer/Doing_Meta_Analysis_in_R/

Hesketh, T., Lu, L., & Zhu, W. X. (2005). The effect of china’s one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(11), 1171–1176. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr051833

Hou, J. (2015). Changes in the Chinese population’s fertility intentions: 1980–2011. Social Sciences in China, 36(1), 46–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/02529203.2015.1001482

Jin, Y. (2014). Low fertility trap: Therory, facts and lessons. Population Research, 38(01), 3–17.

Kang, C., & Sun, G. (2018). The impact of basic pension insurance system on the fertility desire. Finance and Economics., 3, 67–79.

Li, F., & Feng, X. (2016). The willingness and influencing factors of grandparents’ care for the coming grandchildren in cities. Population and Development, 22(04), 87–96.

Li, Jiapeng. (2017). The literature review on Chinese fertility preferences. Journal of the Postgraduate of Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, 2, 18–21. https://doi.org/10.7868/s0207401x17020066

Li, Jingya. (2017). Women’s fertility desire for a second child: Analysis based on sense of utility and cost of second birth. Journal of Chinese Women’s Studies, 3, 27–39

Lu, R., Stulp, G. & Gauthier, A.H. (2022). Quantifying the sources of heterogeneity of fertility preferences in China. China Population and Development Studies, 6, 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-022-00110-3

Liu, J., & Chen, W. (2019). How low has the fertility rate been in China? Population and Economics, 6, 70–81.

Liu, W., & Xu, A. (2006). The non-economic cost on raising a child–Shanghai as an example. Youth Studies, 10, 25–33.

Liu, Y. (2017). Social endowment insurance pension expectation and willingness to give birth. Population and Development, 4, 30–40.

Lutz, W., Skirbekk, V., & Testa, M. R. (2006). Trap Hypothesis : May Lead to Further Postponement Forces Births in Europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 4(March), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.2307/23025482

Ma, L., Fang, X., Lei, Z., & Cai, X. (2016). Does only child’s gender affect the fertility desire of only-child parents to bear a second child? Population Journal, 38, 17–26.

Mcdonald, P. (2008). Very Low Fertility Consequences, Causes and Policy Approaches. The Japanese Journal of Population, 6(1).

Mu, G. (2013). Face the risk of very low fertility rate. China Policy Review, 12, 78–80.

Mu, G. (2014). Views on the reforms of population and family planning policy in China. Journal of Huazhong Normal University (humanities and Social Sciences), 1, 31–39.

Mu, G. (2021). 提倡生育责任伦理共同体意识. [Advocate the common perception of fertility responsibility and ethics]. Beijing Daily. from http://www.china.com.cn/opinion/think/2021-08/16/content_77695771.htm

Poston, D. L., & Gu, B. (1987). Socioeconomic development, family planning, and fertility in China. Demography, 24(4), 531–551. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061390

Schwarzer, G., Carpenter, J. R., & Rücker, G. (2015). Meta-analysis with R (Vol. 4784). Springer.

Shi, R. (2012). 低生育率陷阱:是事实还是神话? [Low fertility trap: the truth or the myth]. Population Research, 34(02), 107–112

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, É. (2014). Two is best? The persistence of a two-child family ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40(3), 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00691.x

Song, J. (2016). 中国普遍二孩生育的政策环境与政策目标 The Environment and the Purpose of Two-child Policy in China. Population and Economics, 4, 121–126.

Tao, T., & Yang, F. (2011). The Population effect of family planing policy. Population Research, 35(1), 103–112.

Thompson, S. G., & Higgins, J. P. (2002). How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1559–1573.

Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor. Journal of Statistical Software, 36(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03

Wang, G., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, N. (2018). The low fertility trap: The risk of current low fertility and prediction of the future trend of population in China. Youth Exploration, 05, 15–27.

Wang, L. (2019). On China’s Population Policy and Social Development. Journal of China University of Labor Relations, 33(05), 116–124.

Wang, Z., & Liu, T. (2017). A Study on Estimation and Sharing Mechanism of the Two-child Fertility Cost. Population Journal, 39(04), 17–29.

Whyte, M. K., & Gu, S. Z. (1987). Popular response to China’s fertility transition. Population and Development Review, 13(3), 471–493. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973135

Wu, F. (2016). The family policy in Europe and the changes in fertility rate—View on the risk of low fertility trap in China. 社会学研究, 01, 49–72.

Wu, F. (2019). Does the low fertility trap exist?–Observations from the long-term trend of fertility trate in post-fertility- transition countries (areas). Population Research, 4, 50–60.

Xin Hua She. (2015). The “birthbearing” related policy--the “chronicles” of the changes of population policies]. Chinese Government Website. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2015-02/09/content_2816919.html.

XXin Hua She. (2021). 三孩生育政策如何实施?——有关人士回应社会关切-新华网

Yao, C., Wu, F., & Li, J. (2010). 我国城乡居民生育意愿调查研究综述:2000-2008[ The reviews on rural and urban fertility preferences in China: 2000–2008]. Population Journal, 2, 17–22

Yang, J. (2017). Gendered division of domestic work and willingness to have more children in China. Demographic Research, 37(1), 1949–1974. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.62

Yang, J., Chen, W., & Peng, Z. (2008). How long has China been from the very low fertility rate? Population Research, 32(3), 31–39.

Yang, S., Jiang, Q., & Sánchez-Barricarte, J. J. (2022). China’s fertility change: An analysis with multiple measures. Population Health Metrics, 20, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12963-022-00290-7

Yang, Z. (2012). The ingrained low fertilty rate. China Youth Study, 11, 19–23.

Yao, C., Wu, F., & Li, J. (2010). The reviews on rural and urban fertility preferences in China: 2000–2008. Population Journal, 2, 17–22.

Zhai, Z., Chen, J., & Li, L. (2015a). The new changes and trend of the births in China. Population Research, 02, 48–56.

Zhai, Z., Chen, J., & Li, L. (2015b). China’s Recent Total Fertility Rate: New Evidence from the Household Registration Statistics. Population Research, 39(6), 22–34.

Zhao, W., Yang, Y., & Zhi, Z. (2017). The imbalance of cost and benefit, evolution of learning and reinforcement of the regional low fertility rate. Economic Survey, 34(5), 109–115.

Zheng, Z. (2014). The measurements and applications in fertility preferences. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 06, 15–25.

Zheng, Z., Li, Y., & Miao, S. (2009). A study on the cost and benefit of childbearing in the context of low fertility: Findings from Jiangsu survey. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 2, 93–102.

Zhuang, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, Z., Li, C., & Qi, J. (2014). Contemporary fertility preperence in rural and urban China–based on the national survey of fertility preference in 2013. Population Research, 38(3), 3–13.

Funding

This research was supported by scholarship (201707650023) from China Scholarship Council to Rui Lu, and a VENI Grant (451-15-034) from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research to Gert Stulp.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, R., Gauthier, A. & Stulp, G. Fertility preferences in China in the twenty-first century. J Pop Research 40, 8 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09303-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09303-0