Abstract

Background

South Africa (SA) has the greatest HIV prevalence in the world, with rates as high as 40% among pregnant women. Depression is a robust predictor of nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and engagement in HIV care; perinatal depression may affect upwards of 47% of women in SA. Evidence-based, scalable approaches for depression treatment and ART adherence in this setting are lacking.

Method

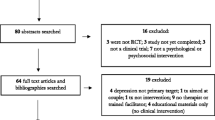

Twenty-three pregnant women with HIV (WWH), ages 18–45 and receiving ART, were randomized to a psychosocial depression and adherence intervention or treatment as usual (TAU) to evaluate intervention feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effect on depressive symptoms and ART adherence. Assessments were conducted pre-, immediately post-, and 3 months post-treatment, and included a qualitative exit interview.

Results

Most (67.6%) eligible individuals enrolled; 71% completed at least 75% of sessions. Compared to TAU, intervention participants had significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms at post-treatment, β = − 11.1, t(24) = − 3.1, p < 0.005, 95% CI [− 18.41, − 3.83], and 3 months, β = − 13.8, t(24) = − 3.3, p < 0.005, 95% CI [− 22.50, − 5.17]. No significant differences in ART adherence, social support, or stigma were found. Qualitatively, perceived improvements in social support, self-esteem, and problem-solving adherence barriers emerged as key benefits of the intervention; additional sessions were desired.

Conclusion

A combined depression and ART adherence intervention appears feasible and acceptable, and demonstrated preliminary evidence of efficacy in a high-need population. Additional research is needed to confirm efficacy and identify dissemination strategies to optimize the health of WWH and their children.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03069417. Protocol available at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03069417

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kharsany ABM, Cawood C, Khanyile D, et al. Community-based HIV prevalence in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: results of a cross-sectional household survey. The Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e427–37.

South African National AIDS Council. 2018 Global AIDS Monitoring Report. 2018. https://sanac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Global-AIDS-Report-2018.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

South Africa National Department of Health. The 2015 National Antenatal Sentinel HIV & Syphilis Survey. 2017.

UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS Statistics — 2019 Fact Sheet. 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

Ramoshaba R, Sithole SL. Knowledge and awareness of MTCT and PMTCT post-natal follow-up services among HIV infected mothers in the Mankweng region. South Africa TOAIDJ. 2017;11:36–44.

Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012;43:683–714.

Rogers A, Obst S, Teague SJ, et al. Association between maternal perinatal depression and anxiety and child and adolescent development: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1082.

Brittain K, Myer L, Koen N, et al. Risk factors for antenatal depression and associations with infant birth outcomes: results from a South African birth cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2015;29:505–14.

van Heyningen T, Myer L, Onah M, et al. Antenatal depression and adversity in urban South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2016;203:121–9.

Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Bärnighausen T, et al. The prevalence and clinical presentation of antenatal depression in rural South Africa. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:362–73.

Manikkam L, Burns JK. Antenatal depression and its risk factors: an urban prevalence study in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J. 2012;102:940.

Zhu Q-Y, Huang D-S, Lv J-D, et al. Prevalence of perinatal depression among HIV-positive women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:330.

Buchberg MK, Fletcher FE, Vidrine DJ, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding barriers to postpartum retention in care among low-income, HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:126–32.

Sheth SS, Coleman J, Cannon T, et al. Association between depression and nonadherence to antiretroviral therapy in pregnant women with perinatally acquired HIV. AIDS Care. 2015;27:350–4.

Osler M, Hilderbrand K, Goemaere E, et al. The continuing burden of advanced HIV disease over 10 years of increasing antiretroviral therapy coverage in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:S118–25.

Chilongozi D, Wang L, Brown L, et al. Morbidity and mortality among a cohort of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected and uninfected pregnant women and their infants from Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27:808–14.

Peltzer K, Weiss SM, Soni M, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial of lay health worker support for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) in South Africa. AIDS Res Ther. 2017;14:61.

Sha BE, Tierney C, Cohn SE, et al. Postpartum viral load rebound in HIV-1-infected women treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol A5150. HIV Clin Trials. 2011;12:9–23.

Kuhn L, Kasonde P, Sinkala M, et al. Does severity of HIV disease in HIV-infected mothers affect mortality and morbidity among their uninfected infants? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1654–61.

Ashaba S, Kaida A, Coleman JN, et al. Psychosocial challenges facing women living with HIV during the perinatal period in rural Uganda. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176256.

Choi KW, Smit JA, Coleman JN, et al. Mapping a syndemic of psychosocial risks during pregnancy using network analysis. IntJ Behav Med. 2019;26:207–16.

Psaros C, Remmert JE, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HIV care after pregnancy among women in sub-Saharan Africa: falling off the cliff of the treatment cascade. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:1–5.

Brittain K, Mellins CA, Phillips T, et al. Social support, stigma and antenatal depression among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:274–82.

Psaros C, Smit JA, Mosery N, et al. PMTCT adherence in pregnant South African women: the role of depression, social support, stigma, and structural barriers to care. Ann Behav Med. 2020;54:626–36.

Peltzer K, Ramlagan S. Perceived stigma among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: a prospective study in KwaZulu-Natal. South Africa AIDS Care. 2011;23:60–8.

Hodgson I, Plummer ML, Konopka SN, et al. A systematic review of individual and contextual factors affecting ART initiation, adherence, and retention for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9:e111421.

Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2528–39.

Gourlay A, Birdthistle I, Mburu G, et al. Barriers and facilitating factors to the uptake of antiretroviral drugs for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18588.

Onono M, Owuor K, Turan J, et al. The role of maternal, health system, and psychosocial factors in prevention of mother-to-child transmission failure in the era of programmatic scale up in western Kenya: a case control study. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:204–11.

Futterman D, Shea J, Besser M, et al. Mamekhaya: a pilot study combining a cognitive-behavioral intervention and mentor mothers with PMTCT services in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1093–100.

Kapetanovic S, Dass-Brailsford P, Nora D, et al. Mental health of HIV-seropositive women during pregnancy and postpartum period: a comprehensive literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:1152–73.

Kaaya SF, Blander J, Antelman G, et al. Randomized controlled trial evaluating the effect of an interactive group counseling intervention for HIV-positive women on prenatal depression and disclosure of HIV status. AIDS Care. 2013;25:854–62.

Mundell JP, Visser MJ, Makin JD, et al. The impact of structured support groups for pregnant South African women recently diagnosed HIV positive. Women Health. 2011;51:546–65.

Tsai AC, Tomlinson M, Comulada WS, et al. Intimate partner violence and depression symptom severity among South African women during pregnancy and postpartum: population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1001943.

Tuthill EL, Pellowski JA, Young SL, et al. Perinatal depression among HIV-infected women in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa: prenatal depression predicts lower rates of exclusive breastfeeding. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1691–8.

Colvin CJ, Konopka S, Chalker JC, et al. A systematic review of health system barriers and enablers for antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108150.

Geldsetzer P, Yapa HMN, Vaikath M, et al. A systematic review of interventions to improve postpartum retention of women in PMTCT and ART care. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20679.

Dyer TP, Stein JA, Rice E, et al. Predicting depression in mothers with and without HIV: the role of social support and family dynamics. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2198–208.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, le Roux IM, Tomlinson M, et al. Philani Plus (+): a Mentor Mother community health worker home visiting program to improve maternal and infants’ outcomes. Prev Sci. 2011;12:372–88.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Richter LM, van Heerden A, et al. A cluster randomized controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of peer mentors to support South African women living with HIV and their infants. PLoS One 2014;9:e84867.

Kwalombota M. The effect of pregnancy in HIV-infected women. AIDS Care. 2002;14:431–3.

Bell AC, D’Zurilla TJ. Problem-solving therapy for depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:348–53.

Nezu A, Maguth Nezu C, D’Zurilla T. Problem-solving therapy: a treatment manual. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2013.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh C, Tan JY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28:1–10.

Lecrubier Y, Sheehan D, Weiller E, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786.

Rochat TJ, Tomlinson M, Newell M-L, et al. Detection of antenatal depression in rural HIV-affected populations with short and ultrashort versions of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16:401–10.

Lawrie TA, Hofmeyr GJ, De Jager M, et al. Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale on a cohort of South African women. S Afr Med J. 1998;88:1340–4.

Mokwena K, Masike I. The need for universal screening for postnatal depression in South Africa: confirmation from a sub-district in Pretoria. South Africa IJERPH. 2020;17:6980.

Lu M, Safren SA, Skolnik PR, et al. Optimal recall period and response task for self-reported HIV medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:86–94.

AARDEX Corporation. Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS). Zug, Switzerland: AARDEX Corporation. https://www.aardexgroup.com/solutions/mems-adherence-hardware/. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

Safren SA, O’Cleirigh CM, Bullis JR, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected injection drug users: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:404–15.

Safren SA, Bedoya CA, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for adherence and depression in patients with HIV: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. The Lancet HIV. 2016;3:e529–38.

Safren SA, Hendriksen ES, Desousa N, et al. Use of an on-line pager system to increase adherence to antiretroviral medications. AIDS Care. 2003;15:787–93.

Holzemer WL, Uys LR, Chirwa ML, et al. Validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument—PLWA (HASI-P). AIDS Care. 2007;19:1002–12.

Antelman G, Smith Fawzi MC, Kaaya S, et al. Predictors of HIV-1 serostatus disclosure: a prospective study among HIV-infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam. Tanzania AIDS. 2001;15:1865–74.

Epino HM, Rich ML, Kaigamba F, et al. Reliability and construct validity of three health-related self-report scales in HIV-positive adults in rural Rwanda. AIDS Care. 2012;24:1576–83.

Dietz P, Bombard J, Mulready-Ward C, et al. Validation of self-reported maternal and infant health indicators in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:2489–98.

Lilliefors HW. On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality with mean and variance unknown. J Am Stat Assoc. 1967;62:399–402.

IBM Corp. SPSS. 2012.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2020. http://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, et al. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. 2021. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

Glaser BG, Strauss AL, Strutzel E. The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nurs Res. 1968;17:364.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Drawing valid meaning from qualitative data: toward a shared craft. Educ Res. 1984;13:20–30.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: procedures and techniques for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

QSR International. NVivo Softw. 2018.

Hartley M, Tomlinson M, Greco E, et al. Depressed mood in pregnancy: prevalence and correlates in two Cape Town peri-urban settlements. Reprod Health. 2011;8:9.

Peltzer K, Rodriguez VJ, Jones D. Prevalence of prenatal depression and associated factors among HIV-positive women in primary care in Mpumalanga province, South Africa. SAHARA-J: J Soc Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2016;13:60–67.

Stellenberg EL, Abrahams JM. Prevalence of and factors influencing postnatal depression in a rural community in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2015;7. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v7i1.874.

Cook JA, Cohen MH, Burke J, et al. Effects of depressive symptoms and mental health quality of life on use of highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-seropositive women. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:401–9.

Koenig LJ, O’Leary A. Improving health outcomes for women with HIV: the potential impact of addressing internalized stigma and depression. AIDS. 2019;33:577–9.

Torres TS, Harrison LJ, La Rosa AM, et al. Quality of life among HIV-infected individuals failing first-line antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. AIDS Care. 2018;30:954–62.

Knettel BA, Cichowitz C, Ngocho JS, et al. Retention in HIV care during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the option B+ era: systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in Africa. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:427–38.

Phillips TK, Clouse K, Zerbe A, et al. Linkage to care, mobility and retention of HIV-positive postpartum women in antiretroviral therapy services in South Africa. J Intern AIDS Soc. 2018;21:e25114.

Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:567–73.

Bennett DS, Traub K, Mace L, et al. Shame among people living with HIV: a literature review. AIDS Care. 2016;28:87–91.

Himelhoch S, Medoff DR, Oyeniyi G. Efficacy of group psychotherapy to reduce depressive symptoms among HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:732–9.

Shibasaki WM, Martins RP. Simple randomization may lead to unequal group sizes. Is that a problem? Am JOrthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2018;154:600–605.

Nakasujja N, Vecchio AC, Saylor D, et al. Improvement in depressive symptoms after antiretroviral therapy initiation in people with HIV in Rakai. Uganda J Neurovirol. 2021;27:519–30.

Hanlon C. Maternal depression in low- and middle-income countries. Int Health. 2013;5:4–5.

Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, et al. No health without mental health. The Lancet. 2007;370:859–77.

Besser M. Mothers 2 Mothers. Search Results Web results South African Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2006;12:122–8.

Barnett ML, Lau AS, Miranda J. Lay health worker involvement in evidence-based treatment delivery: a conceptual model to address disparities in care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:185–208.

Honikman S, van Heyningen T, Field S, et al. Stepped care for maternal mental health: a case study of the perinatal mental health project in South Africa. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001222.

Vythilingum B, Field S, Kafaar Z, et al. Screening and pathways to maternal mental health care in a South African antenatal setting. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013;16:371–9.

Iyun V, Brittain K, Phillips TK, et al. Prevalence and determinants of unplanned pregnancy in HIV-positive and HIV-negative pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019979.

Farquhar C, Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, et al. Antenatal couple counseling increases uptake of interventions to prevent HIV-1 transmission. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37:1620–6.

Hampanda K, Abuogi L, Musoke P, et al. Development of a novel scale to measure male partner involvement in the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:291–303.

Matseke MG, Ruiter RAC, Rodriguez VJ, et al. Factors associated with male partner involvement in programs for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in rural South Africa. IJERPH. 2017;14:1333.

Montgomery E, van der Straten A, Torjesen K. “Male involvement” in women and childrenʼs HIV prevention: challenges in definition and interpretation. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:e114–6.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) under grant K23MH096651 (PI Psaros), with some of the investigator effort supported by 9K24DA040489 (Safren) and T32MH116140 (Stanton). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of all institutional and/or national research committees and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

Steven Safren receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Guilford Publications, and Springer/Humana Press for book royalties related to cognitive behavioral therapy and other evidenced-based treatments. The other authors of this manuscript have declared no conflicts of interest.

Welfare of Animals

No studies were performed with animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dr. Greer Raggio and Elsa S. Briggs were affiliated with the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, MA, at the time the research was conducted. Dr. Raggio is now primarily affiliated with the National Center for Weight and Wellness in Washington, DC, and Ms. Briggs is now primarily affiliated with the Department of Health Systems & Population Health at the University of Washington in Seattle, WA.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Psaros, C., Stanton, A.M., Raggio, G.A. et al. Optimizing PMTCT Adherence by Treating Depression in Perinatal Women with HIV in South Africa: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Int.J. Behav. Med. 30, 62–76 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10071-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10071-z