Abstract

Background

We previously demonstrated that automated, Web-based pain coping skills training (PCST) can reduce osteoarthritis pain. The present secondary analyses examined whether this program also changed coping strategies participants identified for use in hypothetical pain-related situations.

Method

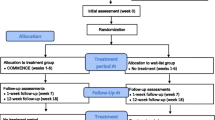

People with hip/knee osteoarthritis (n = 107) were randomized to Web-based PCST or standard care control. At baseline and post-intervention, they reported their pain severity and impairment, then completed a task in which they described how they would cope with pain in four hypothetical pain-related situations, also reporting their perceived risk for pain and self-efficacy for managing it. We coded the generated coping strategies into counts of adaptive behavioral, maladaptive behavioral, adaptive cognitive, and discrete adaptive coping strategies (coping repertoire).

Results

Compared to the control arm, Web-based PCST decreased the number of maladaptive behavioral strategies generated (p = 0.002) while increasing the number of adaptive behavioral strategies generated (p = 0.006), likelihood of generating at least one adaptive cognitive strategy (p = 0.01), and the size of participants’ coping repertoire (p = 0.009). Several of these changes were associated with changes in pain outcomes (ps = 0.01 to 0.65). Web-based PCST also reduced perceived risk for pain in the situations (p = 0.03) and increased self-efficacy for avoiding pain in similar situations (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Salutary changes found in this study appear to reflect intervention-concordant learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hootman JM, Helmick CG, Barbour KE, Theis KA, Boring MA. Updated projected prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation among US adults, 2015–2040. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1582–7.

Barbour KE, Helmick CG, Boring M, Brady TJ. Vital signs: prevalence of doctor-diagnosed arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitation - United States, 2013–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:246–53.

Martel-Pelletier J, Barr AJ, Cicuttini FM, et al. Osteoarthritis Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16072.

Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis Lancet. 2019;393:1745–59.

Kolasinski KL, Neogi T, Hochberg HC, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72:149–62.

Keefe FJ, Porter L, Somers T, Shelby R, Wren AV. Psychosocial interventions for managing pain in older adults: outcomes and clinical implications. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111:89–94.

Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating arthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:210–6.

Dixon KE, Keefe FJ, Scipio CD, Perri LM, Abernethy AP. Psychological interventions for arthritis pain management in adults: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2007;26:241–50.

Broderick JE, Keefe FJ, Bruckenthal P, et al. Nurse practitioners can effectively deliver pain coping skills training to osteoarthritis patients with chronic pain: A randomized, controlled trial. Pain. 2014;155:1743–54.

Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, et al. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001;17:52–64.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Somers TJ, Wren AA, Shelby RA. The context of pain in arthritis: self-efficacy for managing pain and other symptoms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:502–8.

Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: current state of the science. J Pain. 2004;5:195–211.

Merluzzi TV, Pustejovsky JE, Philip EJ, Sohl SJ, Berendsen M, Salsman JM. Interventions to enhance self-efficacy in cancer patients: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychooncology. 2019;28:1781–90.

Marks R. Self-efficacy and arthritis disability: an updated synthesis of the evidence base and its relevance to optimal patient care. Health Psychol Open. 2014;1:2055102914564582.

Jackson T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fan H. Self-efficacy and chronic pain outcomes: a meta-analytic review. J Pain. 2014;15:800–14.

Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, Duggan GB, Rosser BA, Keogh E. Psychological therapies (Internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD010152.

Macea DD, Gajos K, Daglia Calil YA, Fregni F. The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain. 2010;11:917–29.

Bender JL, Radhakrishnan A, Diorio C, Englesakis M, Jadad AR. Can pain be managed through the Internet? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain. 2011;152:1740–50.

REDACTED FOR BLIND REVIEW.

Baumeister H, Reichler L, Munzinger M, Lin J. The impact of guidance on Internet-based mental health interventions: a systematic review. Internet Interventions. 2015;1:205–15.

Rini C, Porter LS, Somers TJ, McKee DC, Keefe FJ. Retaining critical therapeutic elements of behavioral interventions translated for delivery via the Internet: recommendations and an example using pain coping skills training. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014;16:e245.

Theim KR, Sinton MM, Stein RI, et al. Preadolescents’ and parents’ dietary coping efficacy during behavioral family-based weight control treatment. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41:86–97.

Drapkin RG, Wing RR, Shiffman S. Responses to hypothetical high risk situations: do they predict weight loss in a behavioral treatment program or the context of dietary lapses? Health Psychol. 1995;14:427–34.

Chaney EF, O’Leary MR, Marlatt GA. Skill training with alcoholics. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:1092–104.

Jordan JM. An ongoing assessment of osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians in North Carolina: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2015;126:77–86.

Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:505–14.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–1049.

Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40:771–81.

Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:561–6.

Simkin LR, Gross AM. Assessment of coping with high-risk situations for exercise relapse among healthy women. Health Psychol. 1994;13:274–7.

Grilo CM, Shiffman S, Wing RR. Relapse crises and coping among dieters. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:488–95.

Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:37–44.

Lorig K, Holman H. Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scales measure self-efficacy. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:155–7.

Meenan RF, Mason JH, Anderson JJ, Guccione AA, Kazis LE. AIMS2. The content and properties of a revised and expanded Arthritis Impact Measurement Scales Health Status Questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1–10.

Martinez-Calderon J, Jensen MP, Morales-Asencio JM, Luque-Suarez A. Pain catastrophizing and function in individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin J Pain. 2019;35:279–93.

Rini C, Williams DA, Broderick JE, Keefe FJ. Meeting them where they are: using the Internet to deliver behavioral medicine interventions for pain. Transl Behav Med. 2012;2:82–92.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), part of the National Institutes of Health (R01AR057346). The Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project, from which some participants in this trial were recruited, was supported in part by cooperative agreements S043, S1734, and S3486 from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention/Association of Schools of Public Health; the NIAMS Multipurpose Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disease Center grant P60AR30701; and the NIAMS Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center grants P60AR49465 and P60AR064166. The sponsors who provided financial support for the conduct of the research did not influence study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01638871).

Funding

National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01AR057346).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rini, C., Katz, A.W.K., Nwadugbo, A. et al. Changes in Identification of Possible Pain Coping Strategies by People with Osteoarthritis who Complete Web-based Pain Coping Skills Training. Int.J. Behav. Med. 28, 488–498 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09938-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09938-w