Abstract

Purpose

To compare the embryo outcomes of in vitro fertilization/intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist protocol with follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and with human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG).

Methods

We performed a retrospective cohort study in 465 patients. Stimulation was started by daily FSH injection, and either FSH was continued (FSH alone group) or hMG was administrated (FSH-hMG group) after administration of a GnRH antagonist. Primary outcomes were the embryo profile (number of retrieved, mature, and fertilized eggs, and morphologically good embryos on day 3) and endocrine profile. Secondary outcomes were the doses and durations of gonadotropin. Data were stratified by the patients’ age into two groups: <35 years and ≥35 years.

Results

In patients aged <35 years, the number of retrieved oocytes in the FSH alone group was significantly increased than that in the FSH-hMG group (13.7 vs 9.2, P = 0.04), while there was no difference at other age groups. The FSH-hMG group required a significantly greater amount of gonadotropins at any age (all ages, P < 0.001; <35 years, P = 0.013; ≥35 years, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Exogenous FSH alone is probably sufficient for follicular development and hMG may not improve the embryo profile in a GnRH antagonist protocol across all age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) of assisted reproductive technology (ART), FSH is essential but significance of luteinizing hormone (LH) supplementation is controversial. Recent meta-analyses have shown that human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) leads to higher pregnancy rates than recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (rFSH) in a long gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist protocol [1–3]. The GnRH antagonist protocol is widely used, as well as the GnRH agonist protocol for COS for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intra-cytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). However, whether supplementation of LH is beneficial in this protocol is unclear. A few randomized controlled trials (RCT) reported that highly purified hMG (hp-hMG) and rFSH showed similar outcomes, such as the pregnancy rate, the pregnancy loss rate, and the live birth rate [4, 5].

In contrast, the inhibitory effect of GnRH antagonists on LH secretion and a lower pregnancy rate has been shown in a dose-dependent manner (Ganirelix Dose-finding Study Group, 1998 [6]). Endogenous LH levels may fall too low, particularly in advanced reproductive age women, indicating that the effect of LH supplementation in the GnRH antagonist protocol in older women is debatable. Consequently, the optimal ovarian stimulation protocol according to age needs to be established.

In this study, we aimed to examine the IVF/ICSI outcome in a GnRH antagonist protocol with FSH or hMG among all ages, including older reproductive age. We conducted a retrospective analysis on the embryo and endocrine profiles.

Patients and methods

Study population

A total of 465 patients, 45 years or below, who received ovarian stimulation with a GnRH antagonist protocol in our hospital between April 2008 and May 2012 were retrospectively analyzed.

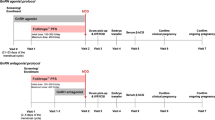

Treatment regimen

On day 2 or 3 of the treatment cycle, ovarian stimulation was started by daily injection of FSH (rFSH; Gonalef® and Follistim®, or urinary FSH (uFSH); Gonapure® and Folyrmon-P®) at a dose of 150–300 IU per day. A daily dose of 0.25 mg of a GnRH antagonist (GANIREST® and Cetrotide®) was initiated when the mean diameter of the lead follicle reached 14–15 mm on transvaginal ultrasound. After administration of a GnRH antagonist, either rFSH/uFSH was continued (FSH alone group) or hMG (HMG Ferring® and HMG TEIZO®) was administrated (FSH-hMG group). The 75 IU of hMG contains 75 IU FSH and 75 IU of LH activity. The dose of rFSH/uFSH and hMG was individually adjusted based on the number and size of follicles and the estradiol level. There were no specific criteria for determining whether FSH or hMG was chosen. When at least two follicles developed to a mean of 16 mm or more in diameter, hCG injection (PREGNYL® 5,000 or 10,000 IU) or GnRH agonist nasal spray (BUSERECUR® 600 μg) was administered to trigger egg maturation. Ultrasound-guided transvaginal egg retrieval was performed 34–35 h later. IVF, ICSI, or a combination of both, was performed according to the condition of the sperm.

Data were stratified by the patients’ age into two groups: <35 years and ≥35 years. In the FSH alone group (313 patients), 49 patients were <35 years and 264 were ≥35 years. In the FSH-hMG group (152 patients), 23 patients were <35 years and 129 were ≥35 years.

Trial end points

Primary outcomes were the number of retrieved oocytes, mature oocytes, normally fertilized (2PN) eggs, and morphologically good embryos on day 3 (D3 good-quality embryos), and hormone levels. Secondary outcomes were the amount of gonadotropin used and the duration of treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD for continuous variables. Normality of distribution of continuous variables was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences between groups of normally distributed variables (hormone levels) were assessed with the Student’s t test, while non-normally distributed variables were evaluated with a non-parametric test (Mann–Whitney test). A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. The patients’ characteristics were similar between the FSH alone group and the FSH-hMG group in each age group, as well as basal hormone levels and antral follicle count.

Endocrine profile

In every age group (total, <35 years, ≥35 years), serum estrogen, LH and progesterone levels on the day of trigger administration were similar between the FSH alone group and the FSH-hMG groups (Table 2).

Egg and embryo profile

In patients aged <35 years, the number of retrieved oocytes in the FSH alone group was significantly increased than that in the FSH-hMG group (13.7 ± 10.2 vs 9.2 ± 4.2, P = 0.04). The number of mature oocytes, the number of fertilized eggs, fertilization rate, and the number of D3 good-quality embryos were similar between the two groups. No differences were observed between the FSH alone group and the FSH-hMG group in patients aged ≥35 years and in total group (Table 3).

Amount of gonadotropin

In patients of every age group, the amount of gonadotropin after starting GnRH antagonists increased in the FSH-hMG group compared with the FSH alone group. This resulted in a significantly higher amount of total gonadotropin administered in the FSH-hMG group though the amount of gonadotropin before a GnRH antagonist using was not different between the two groups. The duration of gonadotropin treatment was similar between the FSH alone and the FSH-hMG groups across all age groups (Table 4).

Logistic regression analysis revealed no correlation between hMG addition and the good embryo outcome, such as nine or more retrieved oocytes (odds ratio (OR):0.76, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.48–1.21) and seven or more mature oocytes (OR: 0.75, 95 % CI 0.51–1.11).

Discussion

This retrospective study showed that administration of hMG in the late follicular phase did not improve the embryo outcome in the GnRH antagonist protocol regardless of age. In addition, our study showed that there were no differences in serum LH, estrogen and progesterone levels with or without hMG administration.

Previous studies comparing FSH and hMG/FSH + rLH in a GnRH antagonist protocol [4, 5, 7–11] are varied in terms of the type of intended patients, the timing for hMG administration, and the type of gonadotropins. Most studies analyzed relatively young women with regard to reproductive age (i.e., women <40 years old with a mean age of 30–33 years). However, currently, women’s age for ART treatment is getting older. In fact, the mean age for ART exceeded 35 years old since 2011 in the United States, and more than half of infertile women in United States and Europe are older than 35 years [12, 13]. Therefore, studies need to be performed in women 40 years or above although there are only a few. Chung et al. [14] performed a retrospective study in 141 cases stratified by an age of <40 years and >40 years. In addition, König et al. [15] conducted a randomized controlled trial in 253 patients only aged >35 years on LH supplementation. Our study was retrospective but included larger numbers of patients (465 patients) with mean age 38.8 years (29–45 years), which consisted of 72 patients (15 %) in <35 years old and 393 patients (85 %) in ≥35 years old. No difference in the embryo and endocrine profile between continuance of rFSH/uFSH and administration of hMG was observed (e.g. the number of retrieved oocytes in total age group, 9.6 ± 6.7 vs 8.5 ± 5.5, N.S.), and it is consistent with those two studies [14, 15].

Our study was designed to compare FSH and hMG in the late follicular phase, whereas some studies started hMG/rLH from the beginning of stimulation [4, 5, 11]. Despite of the timing of starting LH supplementation, hMG/rLH did not improve the embryo profile and increased the amounts of gonadotropins.

With regard to the type and dose of gonadotropin used, the FSH alone group involved both rFSH and uFSH, and hMG contained hp-hMG, not rLH or recombinant hCG. Therefore, quantifying the precise biological activity of gonadotropins was difficult. However, Requena [16] reported that endocrine and follicular profiles were not different between rFSH + rLH and hp-hMG stimulation and previous studies also compared hMG with uFSH [5, 11, 14, 16].

Regardless of these limitations of our study, this is the largest and most practical trial, which included women aged ≥35 years, and hMG was added after a GnRH antagonist.

Furthermore, our evaluation focused on the embryo profile. Most studies investigated the pregnancy or the delivery rate, but those outcomes are affected with a lot of factors, not only quality of embryo, but also number of embryo transferred, local hormone levels, uterine receptivity, and other maternal complications. On the other hand, quality of oocytes and embryos is one of the most relevant factors determining the success of IVF treatment. Among several factors affecting quality of embryos, an ovarian stimulation protocol is eligible and adjustable.

In conclusion, exogenous rFSH/uFSH alone is probably sufficient in the GnRH antagonist protocol for optimal ovarian stimulation to achieve morphologically good embryos across all ages. Moreover, hMG was not beneficial in advanced reproductive age and rFSH/uFSH increased the number of retrieved eggs and subsequently may lead to better embryos in younger normo-gonadotropic patients.

References

Smitz J, Andersen a N, Devroey P, Arce J-C. Endocrine profile in serum and follicular fluid differs after ovarian stimulation with HP-hMG or recombinant FSH in IVF patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:676–87.

Al-Inany HG, Abou-Setta AM, Aboulghar MA, Mansour RTSG. Efficacy and safety of human menopausal gonadotrophins versus recombinant FSH: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16:81–8.

Coomarasamy A, Afnan M, Cheema D, van der Veen F, Bossuyt PMM, van Wely M. Urinary hMG versus recombinant FSH for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation following an agonist long down-regulation protocol in IVF or ICSI treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:310–5.

Bosch E, Vidal C, Labarta E, Simon C, Remohi J, Pellicer A. Highly purified hMG versus recombinant FSH in ovarian hyperstimulation with GnRH antagonists—a randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2346–51.

Devroey P, Pellicer A, Andersen AN, Arce J-C. Trial on behalf of the M in G antagonist C with SET (MEGASET). A randomized assessort-blind trial compareing highly purified hMG and recombinant FSH in a GnRH antagonist cycle with compulsory single-blastocyst transfer. Fertil Steril. 2012;97:561–71.

The Ganirelix Dose-finding Study Group. A double-blind, randomized, dose-finding study to assess the efficacy of the gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist ganirelix (Org 37462) to prevent premature luteinizing hormone surges in women undergoing ovarian stimulation with recombinant follicle. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3023–31.

Griesinger G, Schultze-Mosgau A, Dafopoulos K, Schroeder A, Schroer A, von Otte S, et al. Recombinant luteinizing hormone supplementation to recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone induced ovarian hyperstimulation in the GnRH-antagonist multiple-dose protocol. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1200–6.

Sauer MV, Thornton MH, Schoolcraft W, Frishman GN. Comparative efficacy and safety of cetrorelix with or without mid-cycle recombinant LH and leuprolide acetate for inhibition of premature LH surges in assisted reproduction. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;9:487–93.

Cédrin-Durnerin I, Grange-Dujardin D, Laffy A, Parneix I, Massin N, Galey J, et al. Recombinant human LH supplementation during GnRH antagonist administration in IVF/ICSI cycles: a prospective randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1979–84.

Levi-Setti PE, Cavagna M, Bulletti C. Recombinant gonadotrophins associated with GnRH antagonist (cetrorelix) in ovarian stimulation for ICSI: comparison of r-FSH alone and in combination with r-LH. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:212–6.

Bosch E, Labarta E, Crespo J, Simón C, Remohí J, Pellicer A. Impact of luteinizing hormone administration on gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist cycles: an age-adjusted analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:1031–6.

US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011 Assisted reproductive technology national summary report [internet]. 2011. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov.

Ferraretti AP, Goossens V, Kupka M, Bhattacharya S, De Mouzon J, Castilla JA, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2009: results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2318–31.

Chung K, Krey L, Katz J, Noyes N. Evaluating the role of exogenous luteinizing hormone in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization with gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:313–8.

König TE, van der Houwen LE, Overbeek A, Hendriks ML, Beutler-Beemsterboer SN, Kuchenbecker WK, Renckens CN, Bernardus RE, Schats R, Homburg R, Hompes PGLC. Recombinant LH supplementation to a standard GnRH antagonist protocol in women of 35 years or older undergoing IVF/ICSI: a randomized controlled multicentre study. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:2804–12.

Requena A, Cruz M, Ruiz FJ, García-velasco JA. Endocrine profile following stimulation with recombinant follicle stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone versus highly purified human menopausal gonadotropin. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2014;12:10.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank our embryologists, Mr. Ihana, and his team for laboratory work.

Disclosures

Conflict of interest Chisa Tabata, Toshihiro Fujiwara, Miki Sugawa, Momo Noma, Hiroki Onoue, Maki Kusumi, Noriko Watanabe, Takako Kurosawa and Osamu Tsutsumi declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human rights statements and informed consent All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal rights This article does not contain any studies with animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tabata, C., Fujiwara, T., Sugawa, M. et al. Comparison of FSH and hMG on ovarian stimulation outcome with a GnRH antagonist protocol in younger and advanced reproductive age women. Reprod Med Biol 14, 5–9 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12522-014-0186-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12522-014-0186-0