Abstract

The conservation of ancient Egyptian outdoor carved limestone sculpture is an important issue. This type of artifact is generally exposed to complex weathering processes, and the resulting physico-chemical decay causes unwanted changes in the stone structure and surface. The conservation of carved limestone is a difficult task, requiring the use of materials which need to be compatible to both the original components and those added as part of a previous conservation treatment. The polymeric-nanocomposite materials—which are more and more used on cultural heritage—show promising results for the conservation and preservation of stone monuments, particularly in preventing or reducing future damages. The aims of this study are to characterize limestone used in the outdoor historic sculpture and to examine the efficiency of polymeric nanocomposites in the treatment and preservation of exposed archeological carved limestone. This paper presents a comparative evaluation of the effect of kaolin and calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles to both the mechanical and the physico-chemical properties of an acrylic-based copolymer, in order to enhance significantly the polymer properties and its ability to protect and consolidate the weathered outdoor carved limestone. The polymer nanocomposites were prepared by direct melt mixing with a nanoparticle content of 5% (w/v). The stability and efficiency of the consolidation materials were tested by aging artificially the samples under different environmental conditions. The hydrophobic properties and the adsorption of the treatment materials by the stone were analyzed. Moreover, the properties of untreated and treated limestone samples were evaluated comparatively before and after aging by microstructural analysis (the surface morphology was studied using scanning electron microscopy), by measuring the color variances (using spectrophotometry), and by mechanical tests. The results showed that treatment with Ca(OH) nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposite enhanced the durability of stone samples exposed to artificial aging; moreover, it showed higher compatibility in physico-chemical and mechanical properties with the original stone material compared to the samples treated with polymer nanoparticles. The treatment with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposite was also effective and showed results second to the Ca(OH) nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposite. The test for hydrophobic properties of both nanocomposites also has a positive outcome and no color change on the surface was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Pharaonic city of Tebtunis, located 30 km southwest of El-Fayoum in El-Fayoum area-Egypt, is one of the most famous archeological sites; dating back to an earlier period, it grew and flourished in the Greek and Roman period (Davoli 2012). During the older periods, the archeological city of Tebtunis overlooked the Qarun or old Morris Lake beach (Fig. 1a). The name Tebtunis is the Greek name of the old city, described as “a city of Greek secrets and of 100 thousand papyri”. The city, currently named Um El-Burigat, was mentioned in the Roman period as Tebtunis 1052 times in 707 papyrus documents. The ancient city is one of the most important sources of Greek papyri about the history of Fayoum and Egypt. Approximately 1400 papyri were discovered in Tebtunis city. The historic city counts many buildings, ruins, and archeological discoveries dating back from the ancient times up till the Islamic period Fatimid period. In addition, the great Temple of Sobek (Fig. 1b) was found at the beginning of the Ptolemaic period (Hassan 1986; Brewer 1987).

In this archeological city, there are several structures and artworks that have detailed religious and symbolic scenes carved out of limestone. They suffer from different types of deterioration, mainly pitting, flaking, and disintegration. Being exposed to the open air, buildings and ruins in the historic city show significant physico-chemical and mechanical damages. The effects of such deterioration can be seen on limestone in the form of cracks of different depths, fragility of the surface layer, and complete detachment from the mother limestone. More signs of decay include efflorescence, discoloration, and powdering with consequent loss of the limestone’s surface layer (see Fig. 2). This deterioration phenomenon is the result of the disintegration of the binding materials between the calcite grains. Furthermore, moisture combines with air pollutants to produce acidic water, which severely deleteriorates limestone materials in the outdoor environments (Mabrook et al. 1981; Cassar 2002).

The two recumbent lion statues carved out of limestone, located in front of the road leading to the Temple of Sobek, Tebtunis “Um El-Burigat” city, Fayoum. The different detailed deterioration aspects are shown. a The two statues are exposed to severe damage in the desert environment. b Clear damage in the leg area of the statue, showing fragility, weakness, and distortion. c The side of the statue showing pustules, pitting, and previous completion by lime mortar. d Detailed area in the statue showing pitting and flaking. e The face and mane area of one of the lions showing salt efflorescence and the beginning of flaking and disintegration. (f) The rear of the statue, showing deep pitting, disintegration, and decomposition processes, which are still ongoing due to environmental changes. The final aspect, in this case, is the missing parts and complete detachment, as shown in the neck and rear areas, g cracks in the limestone body, h flaking and exfoliation of limestone due to weathering processes, and i crushed limestone in the surrounding area of the statues and loss of the surface layers of limestone due to severe windstorms and other environmental factors

The conservation of such types of open-air carved limestone always represents a complex task (Griffin et al. 1991). Conservators face many challenges when dealing with exposed carved limestone, particularly the one used in the construction and carving of ancient Egyptian monuments. Its provenance and composition are, in fact, cause itself of decay under weathering factors. The use of limestone in structures and sculptures exposed to environmental deterioration agents makes the conservation process even more difficult requiring fundamental knowledge about the materials used in the construction process and in later refurbishments (Cessari et al. 2009; Aboushook et al. 2006). Therefore, conservators always seek to use conservation materials and techniques with the aim not only to preserve the current state of exposed carved limestone, but also to achieve future preventive effect.

During the last 50 years, various synthetic polymers have been widely used for the preservation and conservation of such structures and art works (Ciabach 1983), especially polymers based on acrylics, lime water, and lime milk which are considered some of the most commonly applied consolidants for limestone, mortar, and plaster (Daniele et al. 2008). In some cases, acrylic was used for “first aid” reversible interventions on the deteriorated carved stone surfaces until more in-depth consolidation could be undertaken (Ashurst 1990).

However, the conservation of outdoor limestone monuments with the use of traditional materials such as polymers coatings and lime water has created serious challenges (La Russaa et al. 2011; El-Gohary 2015; Ruffolo et al. 2017; Belfiore et al. 2012). Conventional products are usually characterized by the lack of compatibility with the original material of the object’s substrate (La Russaa et al. 2012), as they are subject to degradation through the activities of weathering processes and microorganisms. The deterioration of synthetic polymers represents a particular concern to conservators when these are used for the long-term protection of outdoor monuments (Carbó 2008). Moreover, the use of traditional materials results in an incomplete transformation of lime (calcium hydroxide) into calcium carbonate, leaving free particles on the surfaces and reducing the penetration of the material into the stone (Arce and Indart 2015; Dei and Salvadori 2006).

In order to overcome the above drawbacks and limitations during the conservation of outdoor carved limestone, recent conservation studies have focused on some innovative strategies to fill the gap between the traditional conservation methodologies and the most recent methods and discoveries in the field of material science (Mamalis 2007). Recent studies in the field of colloids and materials science led to the development of new conservation treatments based on the use of nanomaterials, to be applied effectively in various scenarios to achieve compatibility between the new substances and the original stone substrate (Ibrahim et al. 2016; Baglioni et al. 2012). Nanomaterials, such as SiO2 nanoparticles, CaCO3 nanoparticles, kaolin nanoparticles, and calcium hydroxide nanoparticles are some of the most common nanomaterials used as fillers and consolidants in archeological stone conservation (Pinho and Mosquera 2013; Manoudis et al. 2008). Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles (nanolime) and kaolin nanoparticles in combination with traditional stone consolidants such as acrylic polymers offer new possibilities for the consolidation and protection of outdoor carved limestone. The aims of the current work are to study the deterioration mechanisms of the carved limestone of Tebtunis city in Fayoum and to evaluate the performance of two nanocomposites combined with acrylic-based co-polymers on the physico-chemical and mechanical properties of deteriorated historic limestone. Calcium hydroxide and kaolin nanoparticles were added as nanometric filler to acrylic polymeric dispersions in order to improve their physico-chemical and mechanical properties. The aims of such nanocomposites are to create suitable compounds to be used in the consolidation and long-term preservation of unique outdoor carved limestone and to devise a concept for the future long-term preventive performance.

The selection of these materials for dealing with such type of limestone monuments was based on their high physical, chemical, and mechanical properties. Calcium hydroxide nanoparticles (nanolime) were chosen for their high physico-chemical and physico-mechanical compatibility with the stone materials, as well as for their ability as consolidation material to control the deterioration action of calcite as binding material in stone structures (Nanni and Dei 2003; Slížková and Drdácký 2015). Also, after the application of calcium hydroxide nanocomposites, during the drying process and evaporation of solvent as well, calcium hydroxide nanoparticles form layers on treated surfaces or within pore structures over time and are converted into CaCO3 by reaction with atmospheric carbon dioxide. The process of conversion of calcium hydroxide into calcium carbonate, called the carbonation process, is determined by several factors such as the exposure to very wet atmospheres containing more than 70% relative humidity (RH), the carbon dioxide concentration, and a suitable time for completion of the reaction, to allow the successful formation of CaCO3. Once the carbonation process is completed, the precipitated product acts as a binder giving the decayed material a more cohesive texture. In building stones, this treatment reinforces the texture and re-aggregates the powdering surfaces (Arizzi et al. 2015; Giorgi et al. 2010; Lopez-Arce et al. 2013).

Kaolin clay, known as white clay, is rich in kaolinite mineral. The kaolinite group contains the minerals kaolinite, dickite, nacrite, and halloysite which are formed as a result of decomposition of orthoclase feldspar (e.g., in granite). Kaolin is the principal component in china clay and can be classified as a layered silicate mineral (1:1 clay) (Fadzil et al. 2017).

Kaolin-polymer nanocomposites are compounds in which clay as a layered silicate is dispersed in nanoscale size in a polymer matrix. Kaolin nanosized layer-filled polymers can exhibit dramatic improvements in the mechanical and thermal properties at low kaolin contents, because of the strong synergistic influence between the polymer and the silicate platelets on both the molecular and nanometric scales (Wilkie 2002; Ray and Okamoto 2003).

The aim of the current study, then, is to investigate the efficiency of selected nanocomposites in the consolidation and protection of archeological outdoor carved limestone located in Tebtunis city, Fayoum (Fig. 2). The obtained nanocomposites were applied directly to limestone samples and tested in order to evaluate the potential uses of calcium hydroxide and kaolin nanoparticles in the consolidation and protection of outdoor carved limestone. Characterization of the limestone samples before and after treatment was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to evaluate the surface morphology and the homogeneous distribution of consolidants on the stone surfaces. The behavior of the nanocomposites exposed to artificial aging was investigated. The physical, chemical, and mechanical properties were determined before and after treatment, as well as with and without artificial aging. The optical appearance was also studied through colorimetric measurements.

Experimental

Materials

Sampling

Set of archeological representative samples were carefully collected from the detached and fallen parts of the carved limestone statues located at the beginning of “Sobek” temple road, in the north side, as shown in Fig. 2 . The study samples were prepared for microscopic investigation, in order to study the mineralogical composition and deterioration mechanism of the carved limestone of Tebtunis city.

Preparation of experimental limestone samples

The experimental limestone blocks (samples) were collected from the quarry of Giza limestone plateau in the western part of greater Cairo, one of the most important limestone quarries in Egypt. Giza and fayoum monuments were constructed mainly from Giza local limestone quarries. Experimental limestone blocks were cut into cubic samples (3 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm) for some tests and into cuboidal samples (10 cm × 10 cm × 2 cm) for other mechanical tests such as surface abrasion test. Used limestone samples are compatible with the chemical composition of the original material of studied archeological limestone. Afterwards, the surface of stone samples was cleaned by soft brush, then washed using distilled water, and dried in an oven at 105 °C for at least 24 h to reach constant weight (Aldoasri et al. 2017b; de Ferri et al. 2011).

Chemicals

Paraloid-B72, purchased from C T S, Rome, Italy, is an acrylic copolymer made of poly ethyl methacrylate (EMA)/methyl acrylate (MA) (70/30, respectively). Nano-powdered kaolin and calcium hydroxide (with particle diameter average < 50 nm) were produced and characterized by Nanografi Nanoteknoloji company—Ankara, Turkey and the data sheet supplied by the company. The acrylic polymer was prepared at 4% w/v concentration, and the nanoparticles were prepared at 5% w/v concentration. The concentration was selected based on the stone nature and porosity, being the limestone in the area of study highly porous and exposed in an outdoor environment; the 5% concentration of treatment materials was found to be appropriate (Buasri et al. 2012; Aldoasri et al. 2017c).

Methodologies

Preparation of the nanocomposites

The obtained nanocomposites were prepared by direct blend-mixing of polymer and nanopowders. Kaolin nanoparticles and Ca(OH)2 nanopowder were dispersed in an aqueous suspension of acrylic polymer (polymer 4% w/v, nanoparticles 0.20 g), and the mixture was held at 75 °C using mechanical stirrer. Subsequently, the mixed compositions were mechanically blended and sonicated for 2 h (Eirasa and Pessan 2009; Kaboorani and Riedl 2011).

The protective nanocomposites tested in this work were applied to the surface of experimental limestone samples by brush at room pressure and temperature. The process was repeated three times, with 2 h interval between each application; then, the treated samples were left to dry off for 30 days at room temperature with controlled RH 50% (Bakr 2011). The samples were weighed again, and the polymer uptake was calculated; then, the treated samples underwent laboratory procedures and artificial aging with the aim of assessing some specific properties of protective materials in relation to the substrate.

Analytical procedures of archeological samples

Some archeological limestone samples have been collected from the objects under study. The samples have been prepared for elemental and mineralogical investigations, to study the mineralogical composition of the studied carved limestone. Thin sections were used for identification of stone minerals by using polarized transmitted light microscopy (PLM), model Nikon opti photo X23 equipped with photo camera S23 under100_ magnification in plane-polarized light. In addition to this, X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used for identification of the mineral composition of the archeological carved limestone samples. The examination was conducted by X-ray diffraction patterns using A “Philips” X-ray diffractometer (PW 3071) (CuKα 40 kV, 30 mA). The scanned 2theta range was 5° to 60°. Moreover, scanning electron microscopy (SEM-EDX) analysis was performed to detect the element contents of collected archeological limestone samples (the SEM–EDX analyses were carried out in FEG Lab; the Egyptian mineral resources authority, Cairo, Egypt).

Artificial aging

Three types of weathering cycles were conducted and termed as “artificial aging”.

Wet-dry weathering cycles

This test was carried out with the aim of evaluating the effect of water on the stone by trying to simulate the climatic changes from sunny to wet rainy weather and simulating the actual environmental deteriorating conditions. For this purpose, the treated samples were put in a temperature-controlled oven, “Herous-Germany”, on special frames. This test consisted of 30 cycles alternatively between wet and drying as follows: 18 h of total immersion in distilled water then 2 h in room temperature and 4 h a temperature-controlled oven at 105 °C (Yang et al. 2007).

Salt-acid weathering

The importance of this test is to evaluate the effect of salts and acidity on stone surface. The samples were exposed to cycles of immersion in a saturated Na2SO4 solution for 4 h; the surface was then sprayed by carbonic acid H2CO3 (3%). Then, the samples were exposed to air in normal room conditions (25 °C and 50% R.H.) for 28 h followed by 16 h in an oven at 105 °C (BS EN 12370 1999).

Photo-oxidative weathering (UV aging)

The photo degradation effect on the consolidation materials and their stability under UV oxidative radiation was evaluated by accelerated aging tests. The test was performed through light emitted by a luminare C.T.S. Art lux 40 with 2 UV fluorescent tubes (5000 K, 45 cm long, 100 W, 220 V), with plexiglas protection screen, with a UV-A component, whose UV intensity was 2 W/cm2. The distance between samples and the light source was 20 cm. The samples were left under UV irradiation for 45 days (Favaro et al. 2006; Male et al. 2005) as shown in Fig. 3.

Morphological analysis of experimental stone samples

The investigation related to the morphological modifications—before and after treatment and after aging—of the experimental stone surface onto which the nanocompounds were applied was performed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The same technique was also used to analyze the behavior of the protective materials on the treated samples and on treated aged samples.

Colorimetry

The application of nanocomposites as protective material and preventive tool in the conservation of cultural heritage and for it should not induce any dramatic variation to the visual aspect of treated surfaces. The color changes induced by protective materials and sample degradation were monitored using a CM-2600d Konica Minolta spectrophotometer. Chromatic values are expressed in CIE L∗a∗b∗ space, where L∗ defines lightness, which can vary from 0 (black) to 100 (white), a∗ denotes red/green values, and b∗ yellow/blue ones, i.e., (+ a) is red, (− a) is green, (+b) is yellow, and (−b) is blue (AA.VV 1993; Schanda 2007).

Characterization of mechanical properties

The archeological carved limestone under study is exposed to the open air, and its surface is always subject to mechanical deterioration. For this reason, the stone surface needs to be reinforced for a better preservation. Two types of mechanical tests mentioned below were conducted.

Compressive strength test

The measurement of compressive strength was carried out using an Amsler compression-testing machine, with the load applied perpendicular to the bedding plane according to ASTM C 170 standard (1976). The test was carried out 1 month after the samples were treated with the protective materials. The average values of compression strength were recorded.

Surface abrasion resistance test

The wide wheel abrasion test was determined according to EN 14157 standard (2004) (Natural Stones—Determination of Abrasion Resistance). Wide wheel abrasion (WWA) tests were applied on samples with dimensions of 10 cm × 10 cm × 2 cm. Samples used in WWA tests were dried at 105 °C for 24 h until they reached a constant weight. The abrasive powder storage hopper was filled with dry powder and placed between the sample and an abrasive rotating disk (Fig. 4). While the abrasive disk rotated at 75 cycles per minute, it was ensured that the flow of friction was uninterrupted. Before starting the experiments, the calibration of the apparatus was checked against a reference sample (Çobanolu et al. 2010). Two surfaces of each sample were tested. At the end of the test, the surface with evidences of abrasion was examined under a loupe and the borders of the abrasion area were depicted. Three measurements were obtained from each abrasion surface, with a 0.01-mm precision digital caliper, and recorded.

Water repellent test

Moisture is considered the most dangerous deterioration factor for outdoor carved limestone, so it is very important that the conservation materials are able to resist the damage caused by water and to reduce water penetration into stone bulk. Therefore, the evaluation of the efficiency of the water repellent treatments is very important and requires the measurement of the static contact angle and of the capillary water absorption.

Static contact angle measurements

Water contact angle measurements of limestone samples were conducted after treatment and artificial aging according to UNI 11207:2007. The test was carried out using distilled water and a custom contact angle measuring instrument made as follows: the stone sample was placed on a sample stage; then, 5 μl water droplets were delivered to the sample from a close distance to the substrate using a graduated micro needle. Then, the needle remained in contact with the liquid droplet and withdrawn with minimal perturbation to the drop. The images of water droplets on the limestone samples were captured using high-resolution Canon camera with a 18–55 lens, and the contact angles were finally calculated and recorded by software program (Helmi and Hefni 2016).

Water absorption test

Moisture is considered the most dangerous deterioration factor for outdoor carved limestone, so it is very important that conservation materials are able to resist to the damage caused by water and reduce water penetration into stone bulk. Therefore, it is very important to evaluate the efficiency of treatments aimed at making the stone water repellent, by measuring its density, its porosity, and its ability to absorb water.

Capillary water absorption measurements were carried out according to UNI 10859 2000, Cultural Heritage—Natural and artificial stones—determination of water absorption by capillarity). Analyses were carried out, in order to assess the coating behavior, on both untreated and treated samples, before and after UV and thermal accelerated aging simulating the solar irradiation—which may lead to a decrease in water resistance. The test was carried out on three samples for each stone species. The limestone samples were completely immersed in deionized water at room temperature. After 24 h, the samples were taken out, wiped with tissue paper carefully, and weighed immediately. The percentage of density, porosity, and absorbed water was calculated using equations (1, 2, and 3, respectively):

where W is the weight and V is the volume

where W1 is the dry weight and W2 is the wet weight

Calculation of water absorption percentage, where W2 is the mass of the sample after immersion in water for 24 h, and W1 is the mass of the sample before immersion.

Results and discussion

Characterization of studied archeological limestone samples

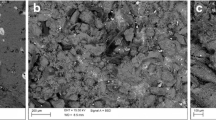

The investigations and analyses of archeological limestone samples, which were carefully collected from fallen fragments in the historic Tebtunis city, are shown in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. The sample investigation confirmed that the archeological limestone sculptures in this area are exposed to dangerous degradation processes. The investigation by thin section of the archeological limestone samples under polarizing light microscope (PLM) showed a large number of fine grained calcite crystals (marked by blue circle), the presence of iron oxides (marked by black circle), quartz crystals (marked by red circle), and clay minerals (marked by green circle) (Fig. 5a). The investigation of archeological sample by SEM (Fig. 5b) showed high ratio of calcite (Ca), quartz (Q), and clay minerals (C.M). Decomposition of calcite crystals and disintegration of the binding materials in stone structure were due to the degradation by physico-chemical weathering and salt crystallization. The charts of X-ray diffraction analysis (Fig. 5c) showed that the archeological limestone sample consists of calcite (CaCO3) and quartz (SiO2) as a major mineralogical constituent, associated with magnesium calcium carbonate CaMg (CO3)2 and hematite (Fe2O3) as impurities.

Investigation of historic limestone samples: a PLM, 100×. The sample consists of calcite crystals (blue circle), quartz crystals (red circle), clay minerals (green circle), clay mineral-rich iron oxides and organic materials (black circle), and b SEM image 3000×. The sample includes calcite (Ca), quartz (Q), clay minerals (CM), and c XRD pattern of archeological limestone sample

The total EDX analysis of the limestone sample (Fig. 6) showed that calcium (Ca) is the dominant element, while sodium (Na), silicon (Si), aluminum (Al), iron (Fe), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), and sulfite (S) were also observed.

Polymer uptake

The polymer uptake values indicated that when nanoparticles are added, the uptake increases probably because of the ability of the nanoparticles to better penetrate within the pores and form a deposit on the limestone samples (Calia et al. 2012; Helmi and Hefni 2016). Following the testing, it was observed that the treatment with Ca(OH)2/polymer nanocomposites achieved the highest value of polymer uptake. This result can be attributed to the higher physical, chemical, and mechanical compatibility with the original stone materials as well as better durability and reversibility. This method has in fact the great advantage of achieving a deeper penetration of the dispersion. Complete data are shown in Table 1.

SEM investigation of stone samples

The surface morphology and distribution of the consolidation materials used in the experimental limestone samples were examined by SEM before and after treatment and after thermal aging. The SEM micrographs of an untreated experimental limestone sample (Fig. 7a) showed pure rounded calcite crystals free from impurities and iron oxides (marked with a red circle). The stone structure appeared to be very fragile and suffered from granular disintegration (marked with a yellow circle). All treatment materials used in this study succeeded in covering the treated limestone grains with a homogenous polymeric networks. However, the high magnification SEM micrographs of samples treated with pure Paraloid B-72 showed that the material has failed to penetrate deep into the stone structure (marked with a yellow circle), and in some areas, the polymer led to the formation of small aggregates (marked with a red circle) (Fig. 7b). The samples treated with Ca(OH)2/polymer nanocomposites (Fig. 7c) showed a more homogenous appearance and was able to penetrate in depth, filling the wide pores between the grains (marked with a blue circle). The Ca (OH) 2/polymer nanocomposites also proved more effective compared to both, the coating with Paraloid B-72 without nanoparticles and the kaolin/polymer nanocomposites. Moreover, no aggregating particles of nanocomposite (marked with blue circle) were observed on the limestone surface. The samples treated with kaolin/polymer nanocomposites (Fig. 7d) also showed a homogeneous and uniform coating on the limestone surface, and the treatment material succeeded in penetrating in depth (marked with a blue circle), but a small aggregation of film coating was noticed in some areas, without any effect on the film uniformity (marked with a red circle). After artificial thermal aging, no significant changes were observed in samples treated with any of the tested products; the film uniformity/homogeneity was affected by aging, which was noted particularly in samples treated with Paraloid B-72 (Fig. 7e). The addition of nanoparticles to the polymer matrix improved the stability of the microstructure of the product under the effect of artificial thermal aging. According to the SEM results, Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles appeared to be the best nanomaterial on limestone, i.e., it filled the polymer matrix, increased the ability of the polymer to penetrate into the stone pores and formed a homogeneous coating. The calcium hydroxide nanoparticles appear to have considerable potential as a consolidating product, achieving a deeper penetration of the dispersion, better stability, and avoiding the formation of white glazing on the treated surface (Ziegenbalg et al. 2010; Ambrosi et al. 2001).

SEM micrographs: a untreated samples, b experimental sample treated with pure Paraloid B72, c experimental sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, d experimental sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, e experimental sample treated with pure Paraloid b72 after artificial aging, f experimental sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging, and g experimental sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging

Colorimetric measurements

Evaluation of color variations of stone samples treated with Paraloid B72 and nanocomposites is expressed by the ΔE parameter, which indicates the difference between each chromatic coordinate (ΔL*, Δa*, and Δb*) in untreated, treated, and treated aged samples. The color variation measurements were performed according to the procedure described in the experimental section. The total color change (ΔE) was calculated using eq. (4):

According to Italian guidelines for the restoration of stone buildings, the ΔE value must be < 5 (NorMal 2017). These parameters are significant for esthetic aspects. In this respect, all the samples after treatment and before artificial aging induced chromatic variations, not visible to the naked eye. However, the ΔE values after exposure to artificial UV and thermal aging had slightly increased compared to the values before aging, especially after thermal aging, the chromatic variations were little higher than after treatment and also after UV aging, but all values were within the acceptable limit (ΔE value < 5), confirming the suitability of the products for conservation purposes. The obtained data are fully listed in Table 2. In order to preserve the original color of surfaces, other authors state that this threshold value should be < 10. The ΔE scale in stone materials conservation is as follows (Limbo and Piergiovanni 2006).

-

ΔE < 0.2: no perceivable difference;

-

0.2 < ΔE < 0.5: very small difference;

-

0.5 < ΔE < 2: small difference;

-

2 < ΔE < 3: fairly perceptible difference;

-

3 < ΔE < 6: perceptible difference;

-

6 < ΔE < 12: strong difference;

-

ΔE > 12: different colors.

Mechanical properties

Compressive strength test

Measurement of mechanical properties of limestone samples in all stages (i.e., untreated, treated, and treated aged) was achieved by the test of compression strength. In Table 3, we can observe the differences in compression strength values for treated and untreated limestone samples. By comparison, it was observed that the results of Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles and kaolin nanoparticles gave the highest values of compressive strength after treatment and following the artificial aging by RH/temperature with significant and acceptable ratio from the conservation point of view. This can be attributed to the effect of the carbonation process on Ca(OH)2 particles in limestone samples, high reactivity, fast reactions in the treated zones, and high compatibility with CaCO3-based substrates (Giorgi et al. 2000; Aldoasri et al. 2017a).The chemical composition of clay, as layered silicates, nanosized-layer-filled polymers can exhibit dramatic improvements in thermal, physical, and mechanical properties at low kaolin contents, because of the strong synergistic effects between the polymer and the silicate platelets on both the molecular and nanometric scales (McNally et al. 2014). The test was carried out on untreated samples only before artificial aging, because after aging, no results were obtained as the sample was too weak to resist (in Table 3, the sample that did not record any results was marked “nd”, i.e., not detected; moreover, the “+” sign refers to improvement in mechanical properties).

Abrasion resistance test

Results of the abrasion resistance test were expressed by the width of the resulting groove in mm. According to the European standard of abrasion resistance test for the stone materials, EN 14157 (2004), the stone surface abrasion values should be not more than 24. Table 4 shows the average values for the abrasion resistance of experimental limestone samples, before and after treatment, and after thermal aging. The results revealed that Ca(OH)2 and kaolin nanoparticles added to the polymer matrix performed best and were the more resistant to abrasive action, thanks to their excellent physical, chemical, and mechanical properties, size, and their higher surface area, as mentioned above. After artificial thermal aging, the surface resistance of samples treated with polymer/nanocomposites was not considerably affected and still gave better results compared to the untreated samples and the samples treated with polymer without the inclusion of nanoparticles as shown in Fig. 8. This may be as a result of nanoparticle properties and their role in enhancing the durability of the stone surface, improving also the interaction with the stone grains (Van Hees et al. 2014) (note: in Table 4, the sample that did not record any results was marked “nd”, i.e., not detected. This is mainly due to the weakness of the sample).

Measurement of abrasion surface in the wide wheel abrasion test: a untreated sample, b sample treated with pure Paraloid B72, c sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, d sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, e sample treated with pure Paraloid B72 after artificial aging, f sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging, and g sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging

Measurements of water contact angle

Figure 9 and Table 5 show equilibrium water contact angle measurements (θ) for the various treatments on studied stones. The “θ” measurement is an average rate obtained by measuring 3 drops (Cappelletti and Fermo 2016). The results showed that nanoparticles enhanced the hydrophobic character of Paraloid B72. In comparison, the treatment with Pure Paraloid B72 had the ability to be water repellent, but it was found to be less hydrophobic than Paraloid B72 added to nanoparticles. Furthermore, Ca(OH)2/polymer nanocomposite achieved the best values for contact angle after treatment and artificial aging, due to the effectiveness of carbonation process on Ca(OH)2 particles, faster carbonation rate, and higher physical, chemical, and mechanical compatibility with the original materials. A slightly less effective performance was achieved by the kaolin–polymer nanocomposites: the differences may be attributed to their chemical properties and hydrophobic character. The values registered did not reach the point of super hydrophobicity. Two important conclusions can be drawn from the results (i) the treatment by pure Paraloid B72 induced a slight increase in the surface hydrophobicity and indicated favorable wetting of the surface; after adding nanoparticles, there was a good increase in θ values and that may induce unfavorable wetting of the surface. However, the results are satisfactory and within the acceptable limits in the stone conservation field because the main purpose is to obtain a reduction in water absorption ratios. This was confirmed in the water absorption test, and the water droplets formed almost perfect spheres with contact angles of less than 150°. (ii) The type of nanoparticles had no substantial effect on super hydrophobicity (contact angles greater than 150°). The surface wettability is not usually governed by the chemical composition of materials but is more likely related to the surface topographic structure, which suggested that this property depends on the nanoscale roughness of the surface that led to the trapping of air between the water droplet and the rough surface, as illustrated in the Cassie-Baxter scenario (Cassie and Baxter 1944; Bico et al. 2002). It should be noted that the obtained results are sufficient to make the stone surfaces more protected from the future damage inform humidity sources. Otherwise, the untreated samples did not manifest any values (referred to that in the Table 5 as “nd”, i.e., not detected). This means total absorption (wettability), due to water spread over the surface.

Drops of distilled water on the surface of the limestone for static contact angle measurement: a untreated samples, b sample treated with pure Paraloid B72, c sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, d sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites, e sample treated with pure Paraloid B72 after artificial aging, f sample treated with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging, and g sample treated with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites after artificial aging

Water absorption

Density, porosity, and capillarity water absorption were measured, in order to assess the decrease in wettability. The results of water absorption test revealed that the addition of Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles to the polymer led to enhancing the results of water absorption values. Furthermore, the results revealed that it is preferable to use calcium hydroxide nanoparticles rather than kaolin nanoparticles, also because of the superficial consolidating and protective effect of the treatment based on the carbonation process and the complete conversion of calcium hydroxide into calcium carbonate by reaction with atmospheric carbon dioxide. Last, but not least, calcium hydroxide nanoparticles are considered more compatible with CaCO3-based substrates than other materials. Note that the test was performed on untreated samples only before artificial aging: after aging, no values could in fact be reported because the material was too weak (referred to that in the Tables 5 and 6 as “nd”, i.e., not detected). In addition, the reduction ratio in water absorption value before and after treatment is significant as the important point in reducing the water penetration inside stone does not prevent all water penetration. Tables 6 and 7 show the average values of density, porosity, and water absorption for the limestone samples before and after treatment as well as after aging (negative sign means that there is a reduction in water absorption ratio).

Salt migration to stone surface

The migration and efflorescence of salts on the surface of a porous stone are one of the serious deterioration factors on stone structure and surface. The conservators always seek to develop the applied techniques and materials to completely and permanently prevent salt efflorescence and protect the archeological stone from the effect of salt weathering (Aldoasri et al. 2016; Marzal and Scherer 2010). The visual investigation of the surface by stereo microscopy showed that treated samples exhibited more resistance than untreated samples. The results also showed that the samples treated with Ca(OH)2 and kaolin nanoparticles had a smoother surface with less visible deteriorations. The treatment with Ca(OH)2/polymer nanocomposite gave the best results in resistance to salt efflorescence on stone surfaces compared to those coated with pure polymer without the nanoparticles. In fact, the nanomaterials in these additives can be up to 100,000 times smaller than even the smallest sand particles and binding materials in stone structure (see Fig. 10a–d).

Conclusions

Outdoor carved limestone monuments are prone to being affected by weathering and environmental deterioration factors. In this study, kaolin and Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles were added to an acrylic-based polymer (EMA/MA) in order to improve its physico-chemical and mechanical properties and determine comparatively what are the best materials to use in the consolidation and protection of the outdoor carved limestone artworks, which can prevent any future damage. The results obtained on the investigation of archeological limestone showed that the samples consist mainly of fine calcite crystals, aluminum, iron, potassium, magnesium, and trace amounts of halite. Samples treated with pure polymer and nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposites were tested under artificial aging. The results showed that the addition of nanoparticles to the acrylic-based polymers improved the ability of polymers to consolidate and protect the limestone samples. The results obtained by colorimetric test, values of polymer uptake, and hydrophobic measurements showed that the treatment by Ca(OH)2 and kaolin/polymer nanocomposites achieved the highest values. However, the experimental evidence showed an effective consolidating action of Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles. The results obtained by SEM microscopic investigation indicated that Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles were the best nanomaterial, which filled the polymer matrix, increased the polymer ability to penetrate into stone pores, and form a homogeneous coating. Moreover, it is observed that the results of Ca(OH)2 and kaolin/polymer nanocomposites achieved the best results in improving the mechanical properties of the polymer and improved its interaction with the stone grains. This can be attributed to the effect of the nanosized filled polymers which exhibited dramatic improvements in mechanical and physio-chemical properties of polymers and their applications. The polymer containing Ca(OH)2 and kaolin nanoparticles could significantly reduce the water absorption rates inside stone bulk, in addition to enhancing the stone durability as compared to pure acrylic polymer. The study confirmed that Ca(OH)2 and kaolin nanoparticles can be considered good candidates for improving the polymers that are used in the consolidation and protection of outdoor limestone monuments. The above can be summarized as: treatment with Ca(OH)2 nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposite is the best treatment in the case of outdoor carved limestone monuments, followed by the treatment with kaolin nanoparticles/polymer nanocomposite. These treatments, respectively, can protect the historic limestone in open air and prevent future damage.

References

AA.VV (1993) Raccomandazioni NorMal 43/93, Misure Colorimetriche strumentali di Superfici opache, Roma, CNR-ICR

Aboushook M, Park, H.D, Gouda, M, Mazen, O, El-Sohby, M (2006) Determination of the Durability of Some Egyptian Monument Stones Using Digital Image Analysis; IAEG 2006, Paper number 80; The Geological Society of London: London, pp 1–10

Aldoasri MA, Darwish SS, Adam MA, Elmarzugi NA, Ahmed SM (2017a) Protecting of marble stone facades of historic buildings using multifunctional TiO2 Nanocoatings. Sustainability 9(2002):2–15

Aldoasri MA, Darwish SS, Adam MA, Elmarzugi NA, Ahmed SM (2017b) Enhancing the durability of calcareous stone monuments of ancient Egypt using CaCO3 nanoparticles. Sustainability 9(1392):1–17

Aldoasri MA, Darwish SS, Adam MA, Elmarzugi NA, Al-Mouallimi NA, Ahmed SM (2017c) Ca (OH)2 nanoparticles based on acrylic copolymers for the consolidation and protection of ancient Egypt calcareous stone monuments. J Phys Conf Ser 829(1):1–8

Aldoasri MA, Darwish SS, Adam MA, Elmarzugi NA, Al-Mouallimi NA, Ahmed SM (2016) Effects of adding Nanosilica on performance of Ethylsilicat (TEOS) as consolidation and protection materials for highly porous artistic stone. J Mater Sci Eng A 6(7–8):192–204

Ambrosi M, Dei L, Giorgi R, Neto C, Baglioni P (2001) Colloidal particles of ca(OH)2: properties and applications to restoration of frescoes. Langmuir 17:4251–4255

Arce LP, Indart ZA (2015) Carbonation acceleration of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles: induced by yeast fermentation. Appl Phys A Mater Sci Process 120(4):1475–1495

Arizzi A, Villalba GLS, Arce PL, Cultrone G, Fort R (2015) Lime mortar consolidation with nanostructured calcium hydroxide dispersions: the efficacy of different consolidating products for heritage conservation. Eur J Mineral 27:311–323

Ashurst J (1990) Methods of Repairing and Consolidating Stone Buildings. In Ashurst J, and Dimes, F.G, Conservation of Building and Decorative Stone, Butterworth-Heinemann 2, London, p 17

ASTM C. American Society for Testing (1976) And protection of stone Monuments.Standard test methods for compressive strength of natural building stone, ASTM C 170; UNESCO: Paris

Baglioni P, Giorgi R, Chelazzi D (2012) Nano-materials for the conservation and preservation of movable and immovable artworks. Int J Herit Digital Era (Progress in Cultural Heritage Preservation–EUROMED) 1(IS1):313–318

Bakr AM (2011) Evaluation of the reliability and durability of some chemical treatments proposed for consolidation of so called-marble decoration used in 19th century cemetery (Hosh Al Basha), Cairo, Egypt. J Gen Union Arab Archaeol 12:75–96

Belfiore C, Fichera VG, La Russaa FM, Ruffolo AS, Pezzino A (2012) The baroque architecture of Scicli (South-Eastern Sicily): characterization of degradation materials and testing of protective products. Periodico di Mineralogia 81(1):19–33

Bico J, Thiele U, Quéré D (2002) Wetting of textured surfaces. Colloids Surf. A 206:41–46

Brewer JD (1987) Seasonality in the prehistoric Fayoum based on the incremental growth structures of the Nile catfish (Pisces: Clarias). J Archaeol Sci 14:459–472

BS EN 12370 (1999) Natural Stone Test Methods – Determination of Resistance to Salt Crystallisation

Buasri A, Chaiyut N, Borvornchettanuwat K, Chantanachai N, Thonglor K (2012) Thermal and mechanical properties of modified CaCO3/PP nanocomposites. Int J Chem Mol Nucl Mater Metall Eng 6:1–4

Calia A, Masieri M, Baldi G, Mazzotta C (2012) The evaluation of nanosilica performance for consolidation treatment of an highly porous calcarenite, 12th international congress on the deterioration and conservation of stone, Columbia University, New York, pp2–11

Cappelletti G, Fermo P (2016) Hydrophobic and superhydrophobic coatings for limestone and marble conservation. In Smart Composite Coatings and Membranes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, the Netherlands, pp 421–452.

Carbó MT (2008) Novel analytical methods for characterising binding media and protective coatings in artwork. Anal Chim Acta 621(2):109–139

Cassar J (2002) Deterioration of the Globigerina limestone of the Maltese islands. In: Siegesmund S, Weiss T, Vollbrecht A (eds) Natural stone, weathering phenomena, conservation strategies and case studies 205. Geological Society London, London, pp 33–49

Cassie ABD, Baxter S (1944) Wettability of porous surfaces. Trans. Faraday Soc 40:546–551

Cessari L, Cenzia B, Elena G, Maria G (2009) sustainable technologies for diagnostic analysis and restoration techniques: the challenges of the green conservation. Proceedings of the 4th international congress science and Technology for the Safeguard of cultural heritage of the Mediterranean Basin, Cairo, Egypt

Ciabach J (1983) Investigation of the cross-linking of thermoplastic resins affected by ultraviolet radiation. In: Tate JO, Tennent NH, Townsend JH (eds) Proceedings of the symposium resins in conservation. Scottish Society for Conservation and Restoration, Edinburgh, pp 51–58

Çobanolu I, Çelik SB, Alkaya D (2010) Correlation between wide wheel abrasion (capon) and Bohme abrasion test results for some carbonate rocks. Sci Res Essays 5:3398–3404

Daniele V, Taglieri G, Quaresima R (2008) The nanolimes in cultural heritage conservation: characterization and analysis of the carbonatation process. J Cult Herit 39:294–301

Davoli P (2012) The archaeology of Fayoum. In: Rigg C (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt. Oxford Handbooks Online, pp 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199571451.001.0001

de Ferri L, Lottici PP, Lorenzic A, Monteneroc A, Mariani SE (2011) Study of silica nanoparticles – polysiloxane hydrophobic treatments for stone-based monument protection. J Cult Herit 12:356–363

Dei L, Salvadori B (2006) Nanotechnology in cultural heritage conservation: nanometric slaked lime saves architectonic and artistic surfaces from decay. J Cult Herit 7:110–115

Eirasa D, Pessan AL (2009) Mechanical properties of polypropylene/calcium carbonate nanocomposites. Mater Res 12(4):517–522

El-Gohary M (2015) Effective roles of some deterioration agents affecting edfu royal birth house “Mammisi”. Int J Conserv Sci 6(3):349–368

EN 14157 (2004) Natural stones—determination of abrasion resistance, European standard–wide wheel abrasion resistance BS. Czech Republic, European Standard (EN), p p19

Fadzil AM, Muhd Nurhasri SM, Norliyati AM, Hamidah SM, Wan Ibrahim HM, Assrul ZR (2017) Characterization of Kaolin as Nano Material for High Quality Construction. MATEC Web of Conf 103(09019):1–9

Favaro M, Mendichi R, Ossola F, Russo U, Simon S, Tomasin P, Vigato PA (2006) Evaluation of polymers for conservation treatments of outdoor exposed stone monuments. Part I: photo-oxidative weathering. Polym Degrad Stab 91:3083–3096

Giorgi R, Ambrosi M, Toccafondi N, Baglioni P (2010) Nanoparticles for cultural heritage conservation: calcium and barium hydroxide nanoparticles for wall painting consolidation. Chem Eur J 16:9374–9382

Giorgi R, Dei L, Baglioni P (2000) A new method for consolidating wall paintings based on dispersions of lime in alcohol. Stud Conserv 45:154–161

Griffin SP, Indictor N, Koestler JR (1991) The biodeterioration of stone: a review of deterioration mechanism, conservation case histories and treatment. Int Biodeterior 28:187–207

Hassan AF (1986) Holocene lakes and prehistoric settlements of the Western Fayoum. Egypt J Archaeol Sci 13(5):483–501

Helmi MF, Hefni AY (2016) Using nanocomposites in the consolidation and protection of sandstone. Int J Conserv SCI 7(1):29–40

Ibrahim RK, Hayyan M, AlSaadi MA, Hayyan A, Ibrahim S (2016) Environmental application of nanotechnology: air, soil, and water. Environ. Sci Pollut Res Int 14:13754–13788

Kaboorani A, Riedl B (2011) Effects of adding nano-clay on performance of polyvinyl acetate (PVA) as a wood adhesive. Compos Part A 42:1031–1039

La Russaa FM, Barone G, Belfiore MC, Mazzoleni P, Pezzino A (2011) Application of protective products to "Noto" calcarenite (South-Eastern Sicily): a case study for the conservation of stone materials. Environmental. Earth Sci 62(6):1263–1272

La Russaa FM, Ruffolo AS, Rovellaa N et al (2012) Multifunctional TiO2 coatings for cultural heritage. Prog Org Coat 74:186–191

Limbo S, Piergiovanni L (2006) Shelf life of minimally processed potatoes part 1 Effects of high oxygen partial pressures in combination with ascorbic and citric acids on enzymatic browning. Postharvest Biol Technol 39:254–264

Lopez-Arce P, Zornoza-Indart A, Gomez-Villalba LS, Fort R (2013) Short- and longer-term consolidation effects of Portlandite (CaOH)2 nanoparticles in carbonate stones. J Mater Civ Eng 25:1655–1665

Mabrook B, Sweilm F, El Sheikh Shoheib R (1981) Ground water resources in fayoum area. Egypt Desalination 39:295

Male S, Kolar J, Strli CM, Koˇcar D, Fromageotc D, Lemaire J, Haillant O (2005) Photo-Induced Degradation of Cellulose. Polym Degrad Stab 89:64–69

Mamalis AG (2007) Recent advances in nanotechnology. J Mater Process Technol 181:52–58

Manoudis P, Karapanagiotis I, Tsakalof A, Zuburtikudis I, Panayiotou C (2008) Super-hydrophobic polymer/nanoparticle composites for the protection of marble monuments. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on NDT of Art, Jerusalem, Israel, 25–30 May, pp 1–8

Marzal EMR, Scherer WG (2010) Advances in understanding damage by salt crystallization. Acc Chem Res 43(6):897–905

McNally T, Murphy RW, Lew YC, Turner JR, Brennan PG (2014) Polyamide-12 layered silicate nanocomposites by melt blending. Polymer 44:2761–2772

Nanni A, Dei L (2003) Ca (OH) 2 nanoparticles from W/O microemulsions. Langmuir 19(3):933–938

NorMal R (2017) Misure Colorimetric he Strumentali di Superfici opache. Available online:http://www.architettiroma.it/fpdb/consultabc/File/ConsultaBC/Lessico_NorMal-Santopuoli

Pinho L, Mosquera JM (2013) Photocatalytic activity of TiO2–SiO2 nanocomposites applied to buildings: influence of particle size and loading. Appl Catal B Environ 134:205–221

Ray SS, Okamoto M (2003) Polymer/layered silicate nanocomposites: a review from preparation to processing. Prog Polym Sci 28(11):1539–1641

Ruffolo AS, La Russaa FM, Ricca M, Belfiore MC et al (2017) New insights on the consolidation of salt weathered limestone: the case study of Modica stone. B Eng Geol Environ 1:11–20

Schanda J (2007) Colorimetry, Wiley-Interscience John Wiley & Sons Inc, p. 56

Slížková Z, Drdácký M (2015) Consolidation of weak lime mortars by means of saturated solution of calcium hydroxide or barium hydroxide. J Cult Herit 16:452–460

UNI 10859 (2000) Cultural Heritage—Natural and artificial stones—Determination of water absorption by capillarity

Van Hees JPR, Lubelli B, Nijland T, Bernardi A (2014) Compatibility and performance criteria for nanolime consolidants, in: proceedings of the 9th international symposium on the conservation of monuments in the Mediterranean Basin - Monubasin, Ankara

Wilkie C (2002) Recent advanced in fire retardancy of polymer–clay nanocomposite. In: Lewin M, editor. Recent advances in flame retardancy of polymers. Norwalk, CT: Business Communications Co Inc 13, pp 155–160

Yang L, Wang LP, Wang P (2007) Investigation of photo-stability of acrylic polymer Paraloid B72 used for conservation. Sciences of conservation and archaeology 19:54–58

Ziegenbalg G, Brümmer K Pianski J (2010) Nano-lime - a new material for the consolidation and conservation of historic mortars. In: Historic mortars – HMC, and RILEM TC 203-RHM final workshop; edited by Válek J, Groot C, Hughes, J.J, pp 1301 – 1309

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude sincere to King Abdulalziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for the valuable and continuous scientific and moral support. The authors acknowledge the valuable assistance given by Sagita Mirjam Sunara, Vice-Dean for Arts, Science, International Collaboration and ECTS Split, Croatia; Dr. Graham, McMaster, Split, Croatia, and Mr. Hussein Abd El-Kader, Ministry of antiquities, Egypt for their valuable technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sawsan S. Darwish, Sayed M. Ahmed, and Mohammad A. Aldosari conceived and designed the experiments; Sayed M. Ahmed and Mahmoud A. Adam performed the experiments; Sawsan S. Darwish, Nagib A. Elmarzugi, and Mahmoud A. Adam analyzed the data; Mohamed A. Aldosari and Nagib A. Elmarzugi contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; Sawsan S. Darwish and Sayed M. Ahmed wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldosari, M.A., Darwish, S.S., Adam, M.A. et al. Evaluation of preventive performance of kaolin and calcium hydroxide nanocomposites in strengthening the outdoor carved limestone. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 11, 3389–3405 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0741-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-018-0741-4