Abstract

Results derived from the analysis of small carnivores from a burial chamber at the Late Neolithic Çatalhöyük (TP Area) shed light on the socioeconomic significance of stone martens (Martes foina), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and common weasels (Mustela nivalis). All of these are fur-bearing animals, though only the stone marten remains to show evidence that this animal was exploited for its pelt. The evidence consists of the observed skeletal bias (only the head parts and foot bones were present) and skinning marks. Two of five sets of articulated feet are most likely linked with an almost completely preserved human infant skeleton, one of two well-preserved skeletons that were interred on the burial chamber floor. In contrast to these, other human skeletons were found mostly incompletely preserved, though with evidence of articulation. It seems that the articulated forepaws were deliberately incorporated into the structure, most likely as a part of burial practice and ritual behavior. These distinctive deposits, along with rich grave goods, emphasize the uniqueness in the entire Anatolian Neolithic of the assemblage from the burial chamber, which is decorated by a panel incised with spiral motifs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

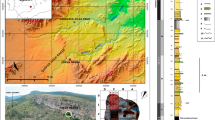

Çatalhöyük (37°23′28″ N, 32°00′10″ E) is a well-documented Neolithic site in Turkey, located in Central Anatolia (Fig. 1). Excavation of the site was initiated in the 1960s by Mellaart (Mellaart 1962, 1963, 1964, 1966) and continues under Hodder to the present day (Hodder 1996, 2000, 2005a, b, c, 2007, 2013a, b). Excavations have focused on the West Mound and the following areas of the East Mound: North, TP, TPC, GDN, Istanbul, and South. The TP Area, discussed here, is located on the southern eminence of the East Mound and comprises the uppermost levels (TP.M–TP.R, Hodder levels) of the mound. Separate strings of levels have been identified for the other areas: South.G–South.T (South Area) and 4040.F–4040.J (North Area) (Farid and Hodder 2014). The main occupational sequence at Çatalhöyük East probably lasted about 950 to 1150 years, beginning in 7100 cal BC and ending between 6200 and 5900 cal BC (e.g., Hodder et al. 2007; Hodder, 2013c with further references; Bayliss et al. 2015). As a result of excavations in the TP Area in 2007, a burial chamber was discovered, containing multiple burials and the small carnivores presented here.

Location of Turkey (outline indicated by black line) in Europe (top) and location of the main sites in Turkey discussed in the text where small carnivore remains were found (bottom). 1: Çatalhöyük (Vulpes vulpes, Martes foina, Mustela nivalis); 2: Sagalassos (M. foina); 3: Ulucak (M. foina, M. nivalis); 4: Karain B and Öküzini caves (V. vulpes, M. foina); 5: Sos Höyük (V. vulpes, M. nivalis); 6: Tilbeşar (V. vulpes); 7: Körtik Tepe (V. vulpes); 8: Göbekli Tepe (V. vulpes, M. nivalis); 9: Troia (M. nivalis)

At Çatalhöyük, carnivores comprise about 2% of the recognizable specimens. Among them, bears, dogs, red foxes, wildcats, leopards, badgers, stone martens, polecats, and weasels are known. The remains of small carnivores from the TP burial chamber reveal the presence of stone martens (Martes foina), red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and common weasels (Mustela nivalis).

Çatalhöyük is well known for its large size (13 ha), complex nature, and animal symbolism, which involves cattle, cervids, boars, and others, as seen in reliefs of animal parts, paintings, and the various configurations of animal parts in relation to the architecture. The most remarkable are the cattle horn cores used as part of the installations and special deposits, as well as in the TP burial, indicating changes in burial rites. Examples of animal parts used as grave goods include bird parts and boar mandibles in two separate burials (Russell et al. 2009a). Foxes, weasels, and even badgers are also present in the animal installations; their purpose might have been apotropaic, since they pose little danger to humans. They are placed almost exclusively on the east wall, where burials often occurred, strongly suggesting some link to the dead, whether to protect the living from ghosts or to keep ancestors safe (Russell and Meece 2005). Mustelids are also found in ritual settings at Çatalhöyük through the deliberate placing of scats within human burials (Jenkins 2012). The role of small carnivores, especially weasels, could also have been more utilitarian, given the abundance of mice. As noted by Jenkins (Jenkins 2012), the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük might have practiced pest control by encouraging small carnivores to enter the site to prey upon rodents, thereby limiting populations.

Today, Turkey is inhabited by several Carnivora species, including wolf (Canis lupus), jackal (Canis aureus), red fox (V. vulpes), brown bear (Ursus arctos), striped hyena (Hyaena hyaena), Anatolian leopard (Panthera pardus tulliana), Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx), caracal (Caracal caracal), jungle cat (Felis chaus), wild cat (Felis silvestris), badger (Meles meles), European polecat (Mustela putorius), marbled polecat (Vormela peregusna), common weasel (M. nivalis), pine marten (Martes martes), stone marten (M. foina), and Egyptian mongoose (Herpestes ichneumon) (Can 2004). The study of Turkish stone martens, of which the first record is known from Tarsus (Mersin province), has revealed that their morphological and biometrical characteristics are consistent with those of Martes foina syriaca (Yiğit et al. 1998). Stone martens are frequently present in human settlements; unlike pine martens, they do not penetrate deeply into forests, preferring the forest edge and open rocky hillsides; other species that live in a very wide range of environments, like the European polecat, generally avoid mountainous areas (Abramov et al. 2016a; Skumatov et al. 2016). Woodland edges and scrub in mixed landscape are also natural habitat of the red fox (Hoffmann & Sillero-Zubiri 2016). The Anatolian red fox (Vulpes vulpes anatolica, Thomas 1920) is present in Anatolia in recent times. Sometimes, a second subspecies, so-called Transcaucasian montaine red fox (Vulpes vulpes kurdistanica Satunin, 1906), is recognized as inhabiting the north-eastern part of Turkey, but is usually synonymized with anatolica. The most fossorial of all weasels, the marbled polecat, is associated with steppe and dry habitats (Abramov et al. 2016b). The common weasel has a wide range of habitats (including forest, cultivated fields, grassy fields and meadows, and scrub) where forms it dens, which is usually related to the local distribution of rodents (for example, medium-sized ground squirrels, such as the Anatolian souslik) (McDonald et al. 2016). Generally, the common weasel in Anatolia differs in size from the European form. Demirbaş and Baydemir (2013) found that specimens from Central Anatolia are larger than European specimens with respect to external and cranial measurements, confirming previous conclusions that extremely large weasels were found in Turkey (Kasparek 1988). The species’ considerable size, and the existence of two types of weasels (nivalis type and minuta type) in Turkey, has often led to the incorrect assumption that the stoat (Mustela erminea) also occurs in Turkey (Kasparek 1988). Interestingly, meat obtained from weasels (local name mangelini), eaten raw or cooked, is a folk remedy for jaundice used today in Central Anatolia, including in Konya province (Sezik et al. 2001). The geographical range of all of these species in Turkey is varied, but is broadest for pine martens, the European polecat, red fox, and common weasel. Stone martens occur only on the outskirts of the country and in the central part, while the marbled polecat is found in the eastern, north-eastern, and central parts of Turkey.

The carnivores of main interest in this study have been noted in archeological research on Turkish sites from various time periods; however, they are usually only listed in species lists, since they constitute a low percentage of assemblages and are typically individual specimens (De Cupere 2001; Howell-Meurs 2001; Peters and Schmidt 2004; Arbuckle and Özkaya 2006; Berthon and Mashkour 2008; Atici 2009; Gündem 2009; Çakırlar 2013; Russell et al. 2013; Pawłowska in press) (Table 1; Fig. 1). One exception is Göbekli Tepe, where fox remains are noted with rather high frequency in the refuse, which could be related to the use of fox pelts and/or the utilization of fox teeth for ornamental purposes (Peters and Schmidt 2004). Against this background, the small carnivores described here are quite numerous and, more importantly, are provided within a single context. The collection’s uniqueness is emphasized by the discovery of small carnivore bones and, regarding the stone martens, by the articulation—along with the evidence of skinning—within the fill of a Late Neolithic burial chamber (TP Area). The aim of this study is to establish the agents most likely responsible for the incorporation of small carnivores into the burial chamber, to evaluate the species diversity, and assess their significance in Neolithic Anatolia. In order to achieve these goals, we combine the taxonomic identification of small carnivores, their body part distribution, evidence of articulation, taphonomic analysis, relationship of their remains to human skeletons in burial chamber, and archeological information on the context. We expect a better understanding of social practices in Late Neolithic Çatalhöyük.

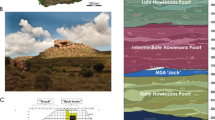

Context

The small carnivores presented in this paper were part of the infill assemblage in the burial chamber of Space 327 (TP.O level) in the TP Area on the East Mound at Çatalhöyük. Space 327 was discovered in 2007 as a rectangular structure, about 2.8 m long and 0.9 m wide (Czerniak and Marciniak 2008) (Fig. 2). The structure had four walls, of which the western wall (as well as the western fragments of the northern and southern walls) was decorated by incised geometric spiral motifs in the form of a rectangular panel. The spiral motif decoration was incised in mud plaster, which was applied to the surface of the mud brick walls (Çamurcuoğlu 2008). The basic pattern of this immobile decorative motif is also seen at the site in portable motifs embodied by stamp seals (Level South.S) (Türkcan 2013). Space 327 is an integral part of Building 74, as suggested by the presence of a doorway between it and another of the building’s spaces (Space 326) (Marciniak and Czerniak 2007). Evidence of burrowing rodents was found, as is the case with most contexts at this site.

At least 10 individuals were interned inside the burial chamber, including at least three infants (Hager and Boz 2008). The bones were densely scattered throughout the northern part of the interior of the structure, with the exception of two nearly complete skeletons (units 17698 and 17622) found in the south part (Czerniak and Marciniak 2008; Hager and Boz 2008). Both skeletons (a female and a child) were found headless. Interestingly, phytolith remains were noted at several places on the female skeleton, including the elbows, suggesting the body was bound prior to interment (Hager and Boz 2008). The head was removed during Neolithic times after the skeleton had fully decomposed (Hager and Boz 2008). In the child skeleton, the presence of the first two cervical vertebrae suggests the deliberate removal of the infant’s head; however, in multiple burials, this might equally be the result of the skeleton being disturbed during other burial events (Hager and Boz 2008). An infant skeleton was lying on its stomach with the right arm bent under the body and the left arm extended by the side of the body. The legs were bent at the knees and crossed under the body (Hager and Boz 2008). Our analysis revealed that the articulated stone marten feet were located exactly by this infant skeleton (unit 17622).

A large number (more than 30) of grave goods were also found in the infill of the structure (Czerniak and Marciniak 2008), including stone beads, flints, obsidian arrowheads, stone axes, a flint dagger, worked bones, pigment, and figurines; none could be associated with any specific individual (Hager and Boz 2008; Carter and Milić 2013; Nakamura and Meskell 2013a). Among the figurines, a notable example is an anthropomorphic miniature figurine delicately carved from stone, possibly marble (Nakamura and Meskell 2013b). The space had some kind of floor, which was not particularly distinct (Czerniak and Marciniak 2008). A foundation was deposited 20 cm underneath, comprising a cluster of animal bones and human bones showing high selectivity by element (Russell et al. 2009b; Pawłowska in press).

According to Marciniak and Czerniak (Marciniak and Czerniak 2007), there are two interpretive possibilities for Space 327: the space was originally built as a dwelling structure and later used as a burial chamber, or it served mortuary purposes from the moment of its construction. It should be emphasized that the emergence of the burial chamber at Çatalhöyük indicates significant changes in burial practice—a departure from burials usually occurring beneath the floors and platforms of houses (Hodder 2014). This is later reinforced by other cases where animal parts are juxtaposed with human remains in burials (Pawłowska in press). In one, a human skull is abutted by a cattle frontlet; in the other, human postcranial parts coincide with goat horn cores (Pawłowska in press, 2014).

Materials and methods

A total of 23,953 animal remains have been investigated from the infill of the burial chamber (Space 327), obtained through dry sieving and flotation. These assemblages were recovered during the 2007 excavation of the TP Area at Çatalhöyük East. Analysis of the flotation samples revealed the presence of the remains of small carnivores (NISP = 56; 0.2% of total assemblage), which were the main focus of our study. They occurred in 11 out of 23 examined samples (Table 2). We attempted to correlate all flotation samples in which small carnivores occurred with human remains found in the burial chamber to determine whether any relation existed (Fig. 3).

The results were based on the number of identified specimens (NISP). Given the minimum number of elements (MNE)—which refers to the minimum number of a particular skeletal portion of a taxon in a particular diagnostic zone (Lyman 1994a)—the specified minimum number of individuals (MNI; White 1953) was calculated. The MNE is the minimum number of skeletal elements necessary to account for an assemblage of specimens of a particular skeletal element (Lyman 1994b). Diagnostic zones are areas on bones that are species-specific in morphology, commonly preserved, used for unfused and fused material, free of age biases, and rarely broken or split (Watson 1979). The MNI was calculated by separating the most abundant element of the species found into right and left components and taking the greater number as the unit of calculation (White 1953).

The dental terminology follows that of Anderson (1970) (Fig. 4). Measurements were made according to the criteria established by Anderson (1970), Ambros (2006), and von den Driesch (1976) (Figs 5 and 6) using an electronic caliper to the nearest 0.1 mm. All measurements are given in mm. The challenge was to compare the measurements of small carnivore bones from the TP Area at Çatalhöyük to measurements from other archeological sites in Turkey. Since these data are scant and selective for various elements of body parts, this was not ultimately possible. For this reason, in this study, all measurements that were possible are offered as guiding data that can be used in future work.

Schematic drawing of marten mandible measurements, following Anderson (1970) and von den Driesch (1976). 1: Total length (condyle to infradentale); 2: angular process to infradentale length; 3: infradentale to anterior margin of masseter fossa; 4: anterior margin of C to posterior margin of M2; 5: cheek teeth row length (anterior margin of P2 to posterior margin of M2); 6: premolar row length (anterior margin of P2 to posterior margin of P4); 7: molar row length (anterior margin of M1 to posterior margin of M2); 8: distance between mental foramens; 9: posterior margin of M2 to condyle length; 10: angular process to coronoid process height; 11: mandible maximal height; 12: mandible body height between P3 and P4; 13: mandible body thickness between P3 and P4; 14: mandible body height between M1 and M2; 15: mandible body thickness between M1 and M2; 16: condyle height; 17: condyle breadth; 18: symphysis maximal diameter; 19: symphysis minimum diameter

Schematic drawing of marten metacarpal measurements, following Anderson (1970), Ambros (2006), and von den Driesch (1976). 1: Greatest length (GL); 2: greatest depth of the proximal end (Dp); 3: greatest breadth of proximal end (Bp); 4: smallest depth of the shaft (DD); 5: smallest breadth of the shaft (SD); 6: greatest depth of the distal end (Dd); 7: greatest breadth of the distal end (Bd)

To determine the age of TP stone martens, they were divided into three age classes (young, juvenile, and adult) based on the degree of wear in the premolar and canine teeth, as established by Albayrak, Özen and Kitchener (2008). For common weasels, age was estimated using King and Powell (2007).

The guidelines of Binford (1981), Greenfield (2004), and Greenfield & Kolska-Horwitz (2012) were used to identify cut marks. Since small-sized carnivore elements can demonstrate species-specific skinning marks (Trolle-Lassen 1987), an actualistic study of the skinning of foxes, badgers, polecats, pine martens, stone martens, and weasels (Val and Mallye 2011) was considered when analyzing cut marks. All taxa considered here are presented within the framework of Val and Mallye (2011) study, which proved useful.

The nature and quantity of all surface modifications originating from carnivore and rodent gnawing, digestion (Lyman 1994a; Fisher 1995), subaerial weathering (Behrensmeyer 1978), and burning were studied.

Several criteria were considered when choosing samples for radiocarbon dating. The first criterion was the presence of the bone in articulation, which indicates they are in their primary undisturbed position, representing short-life samples. Second, the sequence of flotation samples in the infill was considered; this helped determine the time span between the oldest and youngest remains. Finally, given the low mass of the bones—especially in the case of stone martens and common weasels—the weight of the samples for dating also had to be considered. Samples with a mass of about 0.5 g were considered reliable. For this reason, a sample from the bottommost part of the chamber (8723.s35) that lacked the requisite weight could not be used for dating, despite meeting the first two criteria. As a result, the metacarpal bones of stone martens and the tooth fragments of red foxes were used for radiocarbon dating. The dating was conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit Research Laboratory for Archaeology, and the date results are given as uncalibrated radiocarbon years BP.

The rest of the faunal material is not the focus of our study, but to briefly assess it, caprine and cattle bones dominate. Cranial and postcranial elements are present in their body part distribution, though with no evidence of articulation. The majority of bones are fragmented, and none display human modification in the form of cut marks. These quite homogeneous faunal assemblages served as filling material in the structure’s interior.

The animal bones are stored in the depot at Çatalhöyük, and the raw data are available online in the Çatalhöyük database (http://www.catalhoyuk.com/).

Small carnivores in the TP burial chamber

The small carnivores in the burial chamber are mainly stone martens (M. foina Erxleben, 1777; 85.7%), followed by red foxes (V. vulpes Linnaeus, 1758; 10.7%) and common weasels (M. nivalis Linnaeus, 1766; 3.6%) (Table 2). Only cranial parts and autopodial elements (metacarpals and phalanges) were found. The elements are all very slightly weathered (Behrensmeyer’s Weathering Stage 1, Behrensmeyer 1978; 92.9%, n = 52), except for some fox (n = 2) and stone marten (n = 2) elements, which were slightly and moderately weathered, respectively (Behrensmeyer’s Weathering Stages 2 and 3, Behrensmeyer 1978; Table 3). The slightly and moderately weathered parts were found as isolated elements without articulation, and thus were not particularly used in interpreting the data. None of the elements show gnawing, burning, or digestion marks.

Stone (beech) martens

Stone marten remains are predominant among the carnivore remains of the burial chamber (NISP = 48) and belong to two individuals. The most remarkable aspect is that the stone martens are represented solely by cranial parts and the distal parts of limbs in the body part distributions (Tables 4 and 5).

The maxilla is incompletely preserved but has some features with taxonomic potential, such as the originally present first premolar and the extremely short and narrow protocon of the fourth premolar. The mandible body is relatively short, and both oval mental foramens are situated at a distance of 2.1 mm from each other. Although the lower first molar is heavily worn, it is clear that the trigonid is proportionally long and high, the talonid is narrow and short, and the metaconid is not well developed. At least one mandible is from an average-sized male (length of M1 = +10.3 mm; the mean is 9.4 mm for females and 10.2 mm for males; Anderson 1970) (Table 6). All teeth have nonsharp ridges and cusps that are worn by as much as half the crown height, as with the mandibular canine; this indicates an adult age, using the age classes established by Albayrak, Özen and Kitchener (2008).

The metacarpals and phalanges are well preserved and mostly complete (Tables 4 and 5). The metacarpals are short and robust (Table 7). The ratio of the smallest breadth of the shaft to the greatest length of the Çatalhöyük TP metapodials is much closer to the range for foina than for martes (Table 8).

Distal parts of limbs (n = 37) have been found in five sets of articulated elements (Table 4), representing left forelimbs (Fig. 7), right forelimb, metapodials without proximal ends that preclude accurate identification, and digits (A1–A5, respectively, in Fig. 8). Among these, no selective pattern can be observed since both the left and right paws are present. The minimum number of stone marten individuals is two, based on the complete fourth and fifth right metacarpals. The left paw is the most complete, where, additionally, individual elements show cut marks and evidence of pathology. Cut marks are located on the first and fifth metacarpals (medial and lateral parts of the proximal shaft, respectively), on two of the three indeterminate metapodials (the anterior surface of the middle part of the shaft), and on the first phalange (the posterior surface of the proximal shaft and cut-off proximal end of the phalange) (Table 4). Additionally, the first phalanx also displays cut marks on the posterior surface of its proximal shaft (Table 5), all of which are the result of skinning. Bones from the articulated foot with such marks were dated to 7340 ± 40 BP (OxA-X-2499-7) (Fig. 9). The animal bones at Çatalhöyük have low collagen contents, which is also the case here (the sample gave a slightly lower (3.4 mg) than ideal (5 mg) yield of collagen after ultrafiltration). Pathology can be seen on the distal end of the first phalanx as bone overgrowth that could be associated with exostosis, as well as on the distal end of the right fourth metacarpal as inflammation (Tables 4 and 5).

Çatalhöyük East, TP Area, Space 327 (TP.O level). Body part representation of stone marten found in the burial chamber, marked in gray. Pine marten used as template (drawing Michel Coutureau (Inrap), following Cassandre Barraquand, Atlas radiographique et ostéologique de la martre (Martes martes) et de la fouine (Martes foina), Toulouse, 2010). A1–A5: sets of articulated elements; NA specimens found with no articulation; arrows indicate cut marks

Although stone marten remains were found in nine flotation samples, they occurred in greater quantities in one sample (8683.s23) (Table 2). This sample is associated with the almost completely preserved skeleton of an infant (unit 17622) located in the southeast part of the burial chamber.

Red fox

Foxes are represented by five elements (NISP = 6) (Table 2). All specimens agree well with the morphology of the red fox, exemplified by the long and curved character of the canine crown (15839.F483). An isolated upper tooth (M1; 15839.F229 and .F512) comes from a juvenile individual, while other specimens are from adults (Table 9). The first phalange was radiocarbon dated (7415 ± 40 BP, OxA-27310) since it was the sample from the lowest part of the infills that met the criteria for usefulness (Fig. 9).

Common weasel

The size and morphology of the completely preserved mandibles (NISP = 2), which are also the only elements present in the assemblages, allow them to be identified as belonging to common weasels (Table 9). In both cases, the fourth premolar is erupting, indicating the juvenile age of the individual (MNI = 1)—most likely 8–10 weeks of age (King and Powell 2007).

Discussion

Taxonomic significance

The carnivore assemblage from the burial chamber in the TP Area at Çatalhöyük consists of stone martens, red foxes, and common weasels—species that have been previously noted at the site. However, common weasels, for example, have been positively identified in a small number of cases (comprising 2% of the total taxa in the microfauna assemblage, according to Jenkins (Jenkins 2005), and less than 0.05% in the faunal analysis by Russell et al. 2013), all exclusively from earlier levels. Thus, our results extend the knowledge regarding the contribution of small carnivores to the faunal composition of the Late Neolithic.

Stone marten remains can be easily misidentified as belonging to pine martens (or even other mustelids). In our results, the morphological features and metrical data for the cranial parts and metapodials—where the completeness of the specimens is striking—allow us to conclude with certainty that they came from stone martens. This is best illustrated by the distance between both oval mental foramens of the mandible (2.1 mm), which clearly falls into the stone marten range (2.0–3.4 mm) and outside the pine marten range (5.9–9.6 mm) (Anderson 1970). This feature is very distinctive and useful in species identification, since the ranges for these two species do not overlap and are thus mutually exclusive. In addition, the metapodials of the stone marten are proportionally shorter and stouter (Anderson 1970), as is the case here, than for the pine marten. In addition, the size of the metacarpals corresponds to that of an average-sized stone marten (Anderson 1970).

The potential of taxonomic distinction manifests itself in the possibility of using the evidence of stone martens as a bioindicator of Neolithic economy. Southwest Asia and Anatolia are considered the ancestral areas for stone martens, which were already present in this area during the Late Pleistocene. It was from here that the species slowly spread into Europe (Vekua 1994). Zooarchaeological and paleontological records indicate that, while the pine marten is a genuine element of European fauna, the stone marten is a recent colonizer (a post-6 ky BC), whose invasion was fostered by the spread of Neolithic economies. The common marten might have benefited from landscape transformations fostered by Neolithic agropastoral communities (Llorente-Rodríguez et al. 2015). As a result, the species is a faunal bioindicator of the existence of a Neolithic economy in southern Europe (the Iberian Peninsula) (Llorente, Montero and Morales 2011). To our knowledge, the radiocarbon date obtained for the Çatalhöyük stone marten (7340 ± 40 BP) is the first for Neolithic Turkey, indicating the presence of this species in Anatolia at that time—much earlier than the earliest known presence in Europe (6255 ± 35 BP). This date can serve as a starting point for research on the timespan of the stone marten in the archeological record of Turkey.

Fur-bearing value of TP small carnivores

The observed skeletal bias—with only the head parts and foot bones being present—is usually associated with the preparation of game skins. Likewise, in this case, it results from the use of martens for their pelts. In such cases, the foot bones are often attached to the pelts—as, for example, with the red fox evidence from Göbekli Tepe (layer III; Peters and Schmidt 2004). The patterns, however, differ among various fur-bearing animals. At a Mesolithic site in Denmark (Tybrind Vig), for example, it seems that pine martens and otters were skinned differently—the pine martens are represented by complete skeletons, but there is evidence of the head and foot bones being removed from the otter (Trolle-Lassen 1987). Thus, the fur of the feet and snout might have been left on the pine marten carcasses, while the head and foot bones were left with the pelt of the otter (Fairnell and Barrett 2007).

The effect of taphonomic processes on the representation of the elements observed here—in the form of the selective preservation of elements—can be excluded given the low rate of weathering of their bones, which were largely deposited intact. The evidence of the articulations may suggest that there were no significant alterations that could have affected the preservation of the stone marten feet. A well-preserved set of stone martens paws suggests that abiotic factors—such as a soil chemistry or the weight of the overlying sediment—were not destructive, allowing the elements to survive in the assemblage.

The processing of the TP stone martens for their pelts is also corroborated by the evidence of cut marks. Val and Mallye (2011) point out that different cut mark patterns on the anatomical elements of small carnivores are produced depending on the elements that remain in the fur. If all the elements are removed, it is likely that cut marks will be seen on potentially all parts of the distal limbs (phalanges, metapods, carpals, and tarsals). However, when the phalanges remain in the fur, they will not show cut marks on these elements, though the rest of the distal limbs will. In the case of the stone martens from the TP burial chamber, it seems that the foot bones were left in the fur, given the presence and nature of the cut marks on the metacarpals. This is especially true for the paws in A1 and A3 (Fig. 10). This usually occurred when the pelt was used to produce a “trophy” or skin (Fairnell and Barrett 2007). The same breakage pattern is observed in the example of the two metapodials (NA in Fig. 10), which could have come from the same paw. Unfortunately, the lack of proximal ends on all of them precludes accurate identification. Given that stone martens have little or no fur on their feet, especially on the soles (Carter 2004), removing it would be extremely difficult and demand great skill. Thus, the cut marks on some phalanges (A4 and lose finds; n = 2; Fig. 10) seem to have been made incidentally, rather than proving that they were removed from the fur. The fur-bearing value of this species is similar to that of the red fox. Examples of the hunting of martens (mainly pine martens) for fur are also known from Mesolithic sites, which is also associated with the lower value of their meat (Degerbøl 1933; Grundbacher 1992; Stubbe 1993a, b; Richter 2005; Aaris-Sørensen 2009).

Çatalhöyük East, TP Area, Space 327 (TP.O level). Distribution of skinning marks and breakage patterns in articulated sets of paw bones (A1–A5) and bones with no articulation (NA). Arrows indicate cut marks and cross marks indicate missing parts of bones. Mustelid foot (Ambros (2006) with modification) used as template

Although we noted only a few fox elements in the context examined here, foxes are represented at the Neolithic Çatalhöyük by all body parts, with some bias toward heads, which might indicate that skins were brought to the site in addition to whole carcasses. Foxes might have been killed either for their skins or to protect lambs, suggesting that herds were kept closer to the site (Russell et al. 2013). In addition, recent research on a Late Neolithic assemblage at Çatalhöyük (TP Area) revealed that foxes were not numerous (0.3% NISP; 0.5% DZ), and in one case they appeared in an abandonment deposit, where a fox canine was part of the cluster of items spread throughout the interior of the building (Pawłowska in press; Barański et al. 2015). At sites where foxes are observed as the dominant carnivore, or in particular contexts, it is usually the case that they were hunted for their valuable fur, for their ritual significance, or because of their threat to livestock and game (e.g., Russell et al. 2009b; Maher et al. 2011).

The fur-bearing value of the common weasel is not great due to its very small size. However, Fairnell (2003) noted a factor in favor of the value of weasel fur—namely, its distinctive white color in the winter, which is also when it is at its thickest.

Symbolic significance

To understand the small carnivores in the burial chamber, multiple interpretations must be considered, in terms of both natural and cultural factors. The main focus here is on stone martens, which are predominant among the small carnivores and display distinctive patterns, as discussed above.

If the stone martens accidentally fell into the burial chamber and were trapped there, complete skeletons would be expected. Instead, highly selective patterns in the head and feet were observed. It is also hard to imagine this would have happened to two individuals, as shown in our results. Moreover, stone martens are excellent climbers and can jump—their jumping stride can be up to 1 m (Grzimek 1990; Sidorovich 2009)—which ultimately invalidates this hypothesis.

Another potential factor is rodents. There are some signs of burrowing in this context, which might suggest that the presence of stone martens was an effect of rodent activity. Rodents can displace artifacts and ecofacts—as is well recognized in archeological sites, including Çatalhöyük—and thereby have an effect on archeological deposits (Kelly and Thomas 2012). Although rodents can also be responsible for taphonomic bias by removing some skeletal parts from the specific context or even from the site (Wood and Johnson 1978; Bocek 1986), this is unlikely in our case. The selective nature of the stone marten skeletons is more likely result of human factors, as discussed above. For the same reason, this deposit could not represent a den containing dead stone martens. Moreover, this would be inconsistent with the behavior of stone martens, who do not dig burrows or use those made by other animals, such as rodents (Heptner and Naumov 2002).

In addition, the lack of digestion marks in the form of corrosion or pitting excludes the possibility that they came from scats. Since all these natural factors seem unreasonable in assemblage formations, human activity is most likely the cause.

Certainly, none of these features, such as could be the evidence of plaster, indicate that the stone martens’ feet are remnants of a dismantled installation, as is known to be the case with large carnivores based on the example of a bear’s paw at the site (Russell and Martin 2005).

Since burial fill at Çatalhöyük generally contains everyday refuse items (Bennison–Chapman 2013), it would seem unlikely that pelts—which were carefully processed and required effort and skill to produce—would be regarded and rejected as worthless, significantly weakening the other hypothesis that stone marten paws could be a part of the material used to backfill the chamber. Much of this material clearly differs in both composition (ruminants predominating) and characteristics (no articulation or butchery marks, low completeness of the bone) from the stone marten assemblages, indicating the use of general site refuse as fill material. This is also an argument in favor of their intentional placement here.

The interpretation of the stone marten bones as grave goods seems the most plausible. Our results show, as indicated by the coordinates, that in one case the bones could be related to the infant individual. This is even more likely, considering that the infant skeleton is almost complete (Czerniak and Marciniak 2008; Hager and Boz 2008), indicating a relatively undisturbed burial, clearly standing out among the other human remains. Unfortunately, no data exist from the excavation stage showing a detailed relationship between the stone marten remains and the infant skeleton; the evidence of stone marten paws was exclusively revealed as a result of our analysis. Therefore, it is difficult to say whether the articulated stone marten paws were intentionally placed in relation to this individual—to mark identity, for example—or whether they appeared coincidentally. It is certainly telling that the marten feet occurred in the southeastern part of the chamber, in exactly the same place as the infant—despite the fact that human remains, mostly scattered, were present in the northern part of the structure. It does not help that the rare artifacts—which were part of the infilling material of the chamber and deemed to be grave goods—could not be attributed to specific individuals (Hager and Boz 2008).

Accounting for various scenarios, our study of the stone martens leads us to the conclusion that they were deliberately incorporated into the burial chamber, possibly in connection with infant interment. This could then be interpreted as potential personal items or gifts from the mourners, or a combination of the two, as has been suggested for the burial goods (Hamilton 2005; Nakamura and Meskell 2013a). Animal parts as grave goods are not very common in Çatalhöyük burials, with only a few examples: two babies buried with bird parts and a woman buried with three boar mandibles (Russell et al. 2009a). Russell (2012) provided an extensive overview of animal parts in human burials across sites and time periods, along with the social factors shaping animal bone assemblages. She suggested they might function as food offerings for the afterlife, result from funerary feasts or sacrifices, or have symbolic value. The former two are limited to domestic animals, in which case mostly meaty parts should be present (Russell 2012)—which is inconsistent with our results. Instead, nonmeaty parts were present in our study—that is, those parts usually related to symbolism in burial contexts. We suggest, therefore, that stone marten paws were included for their symbolic value as ritual paraphernalia, most likely in connection with the significance of a particular place—specifically, the multiple burials in a decorative burial chamber. This has not previously been observed at the site, and so this association adds to our knowledge of social practices in late Neolithic Çatalhöyük. In addition, there is no evidence for the utilitarian use of small carnivore skins at Çatalhöyük, even though some animal skins were used (leopard, hare, caprine) (Russell 2012 with further references), which also allows us to assume they played a symbolic role in the burial chamber. This is consistent with other evidence of burials where selective animal body parts are present. A ritual connection is postulated in such cases, regardless of the time periods they represent (e.g., Horwitz and Goring-Morris 2004; Grosman, Munro and Belfer-Cohen 2008).

The link between human and animal remains is attested in two subsequent TP burial contexts, indicative of new burial rites (Hodder 2014). In one, a human skull is abutted by a cattle frontlet; in the other, human postcranial parts coincide with goat horn cores (Pawłowska in press, 2014). The architectural dimension of the changes in burial practice is manifested in the chamber construction. This was a departure from burials usually being placed underneath the floors or platforms of houses (Hodder 2014). In this regard, these TP burials are unlike any Çatalhöyük burial.

Two other small carnivore species differ from stone martens in the patterns of body parts and butchery marks. The presence of isolated fox elements in the burial chamber does not point to any symbolic meaning, which aligns with our current general knowledge of the site. Specifically, there is no indication of the symbolic relevance of foxes at Çatalhöyük, despite the generally rich animal symbolism; this contrasts with their frequent depiction in the Levant and southeast Anatolia (Russell et al. 2013 with further references). An example of fox remains in a burial chamber was found in the Van-Yoncatepe necropolis in eastern Anatolia, where five adult foxes, along with human skeletal remains, were found in chamber M4; this, however, is much more recent, dating from the beginning of the first millennium BCE (Onar, Belli and Owen 2005).

The weasel mandibles in the burial chamber are not unusual in terms of the body parts present at Çatalhöyük—namely, cranial material dominates, despite the fact that all body parts are present at the site (Russell et al. 2013). Although our results are not sufficient to suggest any symbolic significance for weasels in the examined context, this aspect is well known for the site. It is manifested in the deliberately placed scats of small carnivores (possibly weasels) in the burials by human inhabitants as part of a ritualistic practice (Jenkins 2012). In addition, a complete weasel skeleton was evidently placed in a burial with carnivore scat (Jenkins 2005; Russell and Meece 2005; Jenkins and Yeomans 2013). Furthermore, Mellaart (1964) found a weasel skull plastered and protruding from the wall, suggesting a ritualized and symbolic association within the community (Nakamura and Meskell 2013a). In that case, however, a lack of access to the specimen complicated identification. Based on its size and proportions, Russell and Meece (2005) regarded it as a mustelid and a member of the weasel family, most likely a badger.

In summary, our results strongly suggest that stone martens had some symbolic value in the burial chamber of the TP Area at Çatalhöyük East as part of the social practices of the Late Neolithic. The articulated feet of the stone marten, resulting from skinning activities, seem to have been intentionally incorporated in the infilled deposits of the structure. If that is the case, they were likely a part of the rituals involved in the mortuary practice.

Factors affecting the presence of small carnivores at Çatalhöyük

The use of martens in such a context raises questions about their procurement, which can be considered in relation to their environmental habitats and behaviors. Martens as a species are strongly associated with rocky and stone habitats, which are not present around the Çatalhöyük settlement since the site is located on the alluvial sediments of a paleolake. However, martens are also among the most synanthropic of carnivorous mammals. Therefore, their distribution has been strongly correlated with human dispersion and occupation, from the Holocene to the present. It seems that the occurrence of stone martens at Çatalhöyük—like the appearance of two other small mustelids, the polecat and the weasel—can be explained by the fact that might have actually lived on the site or entered it at night to hunt (Russell et al. 2013). The use of traps has been suggested as a way of hunting martens (Richter 2005). However, given the absence of complete skulls (only maxilla) in our assemblage, which might be expected to contain lesions, this scenario could not be confirmed. One factor that might explain the presence of stone martens in human habitations is the occurrence in such places of their potential prey—especially rodents (Stubbe 1993a, b). Some of the recent data (concentrations of microfauna from scat assemblages, which appear to have been in situ accumulations) suggests that there were enough mice in the vicinity of Çatalhöyük to sustain the carnivores (Jenkins and Yeomans 2013). Mice, which comprise 96.2% of the total species among the microfauna found at the site (Jenkins 2005), were attracted to the site and took full advantage of the scavenging opportunities provided by the storage food and refuse, as shown by Jenkins and Yeomans (2013), themselves becoming suitable prey for small carnivores. Mice and other rodents might have lived in the narrow spaces between buildings at Çatalhöyük. Although the stone marten prefers animal prey, it is an omnivorous species whose diet also includes honey (its immunity to bee and wasp stings allowing it to obtain this without injury), and even carrion when food is scarce (Carter 2004; Grzimek 1990; Zhou et al. 2011).

The threat weasels pose to livestock is generally exaggerated, but all “weasel-like” animals were (and are) strongly persecuted for this reason (Reichstein 1993a, b; Yalden 1999). The main reason for the presence of weasels in human settlements is rodents; the distribution and abundance of weasels is clearly related to the local population of rodents, since weasel populations are capable of enormous sudden increases, usually associated with “mouse years” (King 1980; King and Powell 2007). Since the weasel is a highly specialized rodent killer (Heidt 1972), it is possible that weasels were attracted to the site by the abundance of house mice (Jenkins 2005). It is also possible that weasels were tolerated at Çatalhöyük because they helped control the mouse population (Hodder 2013c), which is widely known to be the main benefit of this species (e.g., Erlinge 1975; Sullivan and Sullivan 1980). Recently, some evidence for considering small mustelids—such as weasels and polecats—as rodent predators at Çatalhöyük was proposed by Jenkins and Yeomans (Jenkins and Yeomans 2013), who noted the existence of puncture marks on mouse bones.

Conclusion

The reconstruction of mortuary practices helps us understand how people buried their dead and provides insight into mortuary rituals, seen as actively constructing social orders and not as passively reflecting prehistoric societies (Kuijt et al. 2011). Our results show that there is a strong indication that—unlike the other two recognized species, the red fox and the common weasel—the stone marten had some symbolic value in the burial chamber in TP Area at Çatalhöyük East. The articulated feet of the stone marten, resulting from skinning activity, seems to be intentionally incorporated into the infilled deposit of structure, and if so, as part of the rituals that were likely a part of the mortuary practice. They are also highly selective in nature in regards to the animal parts, indicating processing of the animal for its pelt, and not excluding the possibility of funerary use. It is likely that at least two of the paws of the stone marten are associated with a specific human individual. The findings we present here are in line with the other unusual grave goods interred in the TP burial chamber. Several explanations for such grave goods are known. They might be mourner’s gifts to the dead, be selected to serve as reminders of a person’s deeds or character, serve to equip the dead for the world of the afterlife or to prevent the dead coming back to haunt the living, or reflect the position of the deceased (Parker Pearson 1999). Our analysis showed a distinct pattern in the use of small carnivores in the burial context, clearly pointing to burial practice, and thus to social practices, in late Neolithic Çatalhöyük. The role of ritual in the formation of faunal assemblages (Russell 2012) has also been demonstrated.

References

Aaris-Sørensen K (2009) Diversity and dynamics of the mammalian Fauna in Denmark throughout the last glacial–interglacial cycle, 115-0 kyr BP. In: Fossils and Strata Monograph Series 57. Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken

Abramov AV, Kranz A, Herrero J, Choudhury A, Maran T (2016a) Martes foina. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T29672A45202514.en. Accessed 20 May 2017

Abramov AV, Kranz A, Maran T (2016b) Vormela peregusna. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T29680A45203971.en. Accessed 20 May 2017

Albayrak I, Özen AS, Kitchener AC (2008) A contribution to the age-class determination of Martes foina Erxleben, 1777 from Turkey (Mammalia: Carnivora). Turk J Zool 32:147–153

Ambros D (2006) Morphologische und metrische Untersuchungen an Phalangen und Metapodien quartärer Musteliden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Unterscheidung von Baum- und Steinmarder (Martes martes (Linné 1758) und Martes foina (Erxleben 1777)). Der Andere Verlag, Erlangen

Anderson E (1970) Quaternary evolution of the genus Martes (Carnivora, Mustelidae). Acta Zool Fenn 130:1–132

Arbuckle BS, Özkaya V (2006) Animal exploitation at Körtik Tepe: an early aceramic Neolithic site in southeastern Turkey. Paléorient 32:113–136

Atici L (2009) Implications of age structures for epipaleolithic hunting strategies in the western Taurus Mountains, southwest Turkey. Anthropozoologica 44:13–39

Barański MZ, García-Suárez A, Klimowicz A, Love S, Pawłowska K (2015) The architecture of neolithic Çatalhöyük as a process: complexity in apparent simplicity. In: Hodder I, Marciniak A (eds) Assembling Çatalhöyük: themes in contemporary archaeology 1. Maney Publishing, Leeds, pp 111–126

Bayliss A, Brock F, Farid S, Hodder I, Southon J, Taylor RE (2015) Getting to the bottom of it all: a Bayesian approach to dating the start of Çatalhöyük. J World Prehist 28:1–26

Behrensmeyer AK (1978) Taphonomic and ecologic information from bone weathering. Paleobiology 4:150–162

Bennison-Chapman L (2013) Geometric clay objects. In: Hodder I (ed) Substantive Technologies at Çatalhöyük: Reports from the 2000–2008 Seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 48, Monumenta Archaeologica 31, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 253–276

Berthon R, Mashkour M (2008) Animal remains from Tilbeşar excavations, southeast Anatolia, Turkey. Anat Ant 16:23–51

Binford LR (1981) Bones: ancient men and modern myths. Academic Press, New York

Bocek B (1986) Rodent ecology and burrowing behavior: predicted effects on archaeological site formation. Am Antiq 51:589–603

Çakırlar C (2013) Zooarchaeology of neolithic Ulucak: primary dataset. Canan Çakırlar (ed) Open Context. https://opencontext.org/persons/67303C62-0129-48BF-45D3-A15172495D61. Accessed 5 February 2015. Open Context, Web-based research data publication doi: 10.6078/M7KS6PHV

Çamurcuoğlu D (2008) Conservation. Çatalhöyük Research Project, Çatalhöyük 2008, Archive Report, Çatalhöyük, pp 249–256

Can OE (2004) Status, conservation and management of large carnivores in Turkey. In:, Convention on the Natural Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats, 24th meeting, Strasbourg, 29 November-3 December 2004, pp 1–28

Carter K (2004) Martes foina. Animal Diversity Web. http://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Martes_foina/. Accessed 3 February 2015

Carter T, Milić M (2013) The chipped stone. In: Hodder I (ed) Substantive technologies at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons. British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 48, Monumenta Archaeologica 31, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 417–478

Czerniak L, Marciniak A (2008) The excavations of the TP (Team Poznań) Area in the 2008 season. Çatalhöyük Research Project, Çatalhöyük 2008 Archive Report, Çatalhöyük, pp 73–82

De Cupere B (2001) Animals at ancient Sagalassos: evidence of the faunal remains. Studies in eastern Mediterranean archaeology IV. M. Waelkens, Turnhout, Brepols

Degerbøl M (1933) Danmarks Pattedyr i Fortiden i Sammenligning med recente Former. Vidensk Medd fra Dansk Naturh Foren 96:357–641

Demirbaş Y, Baydemir NA (2013) The least weasel (Mustela nivalis) (Mammalia, Carnivora) from central Anatolia: an overview on some biological characteristics. Hacet Bull Nat Sci Eng Ser B 41:365–370

Erlinge S (1975) Predation as a control factor of small rodent populations. Ecol Bull 19:195–199

Fairnell EH (2003) The utilisation of fur-bearing animals in the British Isles. The University of York, York, A zooarchaeological hunt for data. MSC in Zooarchaeology

Fairnell EH, Barrett JH (2007) Fur-bearing species and Scottish islands. J Archaeol Sci 34:463–484

Farid S, Hodder I (2014) Excavation, recording and sampling methodologies. In: Hodder I (ed) Çatalhöyük Excavations: the 2000-2008 Seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 46, Monumenta Archaeologica 29, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 35–51

Fisher JJW (1995) Bone surface modifications in zooarchaeology. J Archaeol Method Th 2:7–68

Greenfield HJ (2004) The butchered animal bone remains from Ashqelon, Afridar-Area G. Antiqot 45:243–261

Greenfield HJ, Kolska-Horwitz L (2012) Reconstructing animal-butchering technology: slicing cut marks from the submerged pottery Neolithic site of neve yam, Israel. In: Seetah K, Gravina B (eds) Bones for tools-tools for bones: the interplay between objects and objectives. University of Cambridge, Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, pp 53–65

Grosman L, Munro ND, Belfer-Cohen A (2008) A 12,000-year-old shaman burial from the southern Levant (Israel). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105:17665–17669

Grundbacher BV (1992) Nachweis des Baummarders, Martes martes, in der neolitischen Ufersiedlung von Twann (Kanton Bern, Sweiz) sowie Anmerkungen zur osteometrischen Unterscheidung von Martes martes und M. foina. Z Säugetierk 57:201–210

Grzimek B (ed) (1990) Animal life encyclopedia. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York

Gündem CY (2009) Animal based economy in Troia and the Troas during the maritime Troy culture (c. 3000-2200 BC.) and a general summary for west Anatolia. Dissertation, Universität Tübingen

Hager LD, Boz B (2008) Human remains archive report 2008. Çatalhöyük Research Project, Çatalhöyük 2008 Archive Report, Çatalhöyük, pp 128–139

Hamilton N (2005) Social aspects of burial. In: Hodder I (ed) Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 38, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London, pp 301–306

Heidt GA (1972) Anatomical and behavioral aspects of killing and feeding by the least weasel, Mustela nivalis L. Ark Acad Sci Proc 26:53–54

Heptner VG, Naumov NP (eds) (2002) Mammals of the Soviet Union, vol II, part 1b, Carnivora (Weasels; Additional Species). Smithsonian Institution Libraries and National Science Foundation, Washington

Hodder I (ed) (1996) On the surface: Çatalhöyük 1993-95. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 22, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2000) Towards reflexive method in archaeology: the example at Çatalhöyük. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 28, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2005a) Çatalhöyük perspectives: reports from the 1995-99 seasons. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 40, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2005b) Changing materialities at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 39, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2005c) Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 38, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2007) Excavating Çatalhöyük: south, north and KOPAL area reports from the 1995-99 seasons. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 37, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London

Hodder I (ed) (2013a) Humans and landscapes of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000–2008 seasons. British Institute at Ankara Monograph No, 47, Monumenta Archaeologica, vol 30. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles

Hodder I (ed) (2013b) Substantive technologies at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000–2008 seasons. British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 48, Monumenta Archaeologica, vol 31. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles

Hodder I (2013c) Dwelling at Çatalhöyük. In: Hodder I (ed) Humans and landscapes of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 47, Monumenta Archaeologica 30. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 1–29

Hodder I (ed) (2014) Religion at work in a Neolithic society: vital matters. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hodder I, Cessford C, Farid S (2007) Introduction to methods and approach. In: Hodder I (ed) Excavating Çatalhöyük: south, north and KOPAL area reports from the 1995-99 seasons, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 37, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, London: British Institute at Ankara, Cambridge, pp 3–24

Hoffmann M, Sillero-Zubiri C (2016) Vulpes vulpes. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T23062A46190249.en. Accessed 20 May 2017

Horwitz LK, Goring-Morris N (2004) Animals and ritual during the Levantine PPNB: a case study from the site of Kfar Hahoresh, Israel. Anthropozoologica 39:165–178

Howell-Meurs S (2001) Archaeozoological evidence for pastoral systems and herd mobility: the remains from Sos Höyük and Büyüktepe Höyük. Int J Osteoarchaeol 11:321–328

Jenkins E (2005) The Çatalhöyük microfauna: preliminary results and interpretations. In: Hodder I (ed) Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 38, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London, pp 111–116

Jenkins E (2012) Mice, scats and burials: unusual concentrations of microfauna found in human burials at the Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük, central Anatolia. J Soc Archaeol 12:380–403

Jenkins E, Yeomans L (2013) The Çatalhöyük microfauna. In: Hodder I (ed) Humans and landscapes of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 47, Monumenta Archaeologica 30. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 259–269

Kasparek M (1988) On the occurrence of the weasel, Mustela nivalis, in Turkey. Zool Middle East 2:8–11

Kelly RL, Thomas DH (2012) Archaeology. Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont

King CM (1980) Population biology of the weasel Mustela nivalis on British game estates. Holarct Ecol 3:160–168

King CM, Powell RA (2007) The natural history of weasels and stoats. In: Ecology, Behavior, and Management. Oxford University Press, New York

Kuijt I, Guerrero E, Molist M, Anfruns J (2011) The changing Neolithic household: household autonomy and social segmentation, Tell Halula, Syria. J Anthropol Archaeol 30:502–522

Llorente L, Montero C, Morales A (2011) Earliest occurrence of the beech marten (Martes foina Erxleben, 1777) in the Iberian Peninsula. In: Brugal J, Gardeisen A, Zucker A (eds) Actes de les XXXIe Rencontres Internationales d’Archeologie et d’Histoire d’Antibes. Prédateurs dans tous les états. Editions APDCA, Antibes, pp 189–209

Llorente-Rodríguez L, Nores-Quesada C, López-Sáez JA, Morales-Muñiz A (2015) Hidden signatures of the Mesolithic–Neolithic transition in Iberia: the pine marten (Martes martes Linnaeus, 1758) and beech marten (Martes foina Erxleben, 1777) from Cova Fosca (Spain). Quat Int 403:174–186

Lyman RL (1994a) Vertebrate taphonomy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lyman RL (1994b) Relative abundances of skeletal specimens and taphonomic analysis of vertebrate remains. PALAIOS 9:288–298

Maher LA, Stock JT, Finney S, Heywood JJN, Miracle PT, Banning EB (2011) A unique human-fox burial from a pre-Natufian cemetery in the Levant (Jordan). PLoS One 6:e15815

Marciniak A, Czerniak L (2007) The excavations of the TP (Team Poznań) Area in the 2007 season. Çatalhöyük Research Project, Çatalhöyük 2007 Archive report, Çatalhöyük, pp 113–123

McDonald RA, Abramov AV, Stubbe M, Herrero J, Maran T, Tikhonov A, Cavallini P, Kranz A, Giannatos G, Kryštufek B, Reid F (2016) Mustela nivalis. 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T70207409A45200499.en. Accessed 20 May 2017

Mellaart J (1962) Excavations at Çatal Hüyük: first preliminary report, 1961. Anat St 12:41–65

Mellaart J (1963) Excavations at Çatal Hüyük: 1962, second preliminary report. Anat St 13:43–103

Mellaart J (1964) Excavations at Çatal Hüyük 1963: third preliminary report. Anat St 14:39–119

Mellaart J (1966) Excavations at Çatal Hüyük, 1965: fourth preliminary report. Anat St 16:165–191

Nakamura C, Meskell L (2013a) The Çatalhöyük burial assemblage. In: Hodder I (ed) Humans and landscapes of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 47, Monumenta Archaeologica 30, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 441–466

Nakamura C, Meskell L (2013b) Figurine worlds at Çatalhöyük. In: Hodder I (ed) Substantive technologies at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 48, Monumenta Archaeologica 31. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 201–234

Onar V, Belli O, Owen RP (2005) Morphometric examination of red fox (Vulpes vulpes) from the Van-Yoncatepe necropolis in eastern Anatolia. Int J Morphol 23:253–260

Parker Pearson M (1999) The archaeology of death and burial. Sutton Publishing, Gloucestershire

Pawłowska K (2014) The smells of Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey: time and space of human activity. J Anthropol Archaeol 36:1–11

Pawłowska K (in press) Animals at late Neolithic Çatalhöyük: subsistence, food processing, and depositional practices. In: Czerniak L, Marciniak A (eds) Late Neolithic at Çatalhöyük east: excavations of upper levels in the team Poznań area. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles

Peters J, Schmidt K (2004) Animals in the symbolic world of pre-pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: a preliminary assessment. Anthropozoologica 39:179–218

Reichstein H (1993a) Mustela erminea. In: Niethammer J, Krapp F (ed) Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas. Band 5: Raubsäuger: Carnivora (Fissipedia). Teil II: Mustelidae 2, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae, AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 533–571

Reichstein H (1993b) Mustela nivalis. In: Niethammer J, Krapp F (ed) Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas. Band 5: Raubsäuger: Carnivora (Fissipedia). Teil II: Mustelidae 2, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae. AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 571–627

Richter J (2005) Selective hunting on pine marten, Martes martes, in late Mesolithic Denmark. J Archeol Sci 32:1223–1231

Russell N (2012) Social Zooarchaeology: humans and animals in prehistory. University Press, Cambridge

Russell N, Martin L (2005) The Çatalhöyük mammal remains. In: Hodder I (ed) Inhabiting Çatalhöyük: reports from the 1995-99 seasons, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 38, Cambridge, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London, pp 355–398

Russell N, Meece S (2005) Animal representations and animal remains at Çatalhöyük. In: Hodder I (ed) Çatalhöyük perspectives: reports from the 1995-99 seasons, British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara Monograph No. 40, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge, British Institute at Ankara, London, pp 209–245

Russell N, Martin L, Twiss KC (2009a) Building memories: commemorative deposits at Çatalhöyük. Anthropozoologica 44:103–125

Russell N, Twiss K, Orton D, Pawłowska K (2009b) Çatalhöyük animal bones 2009. In: Çatalhöyük research project, Çatalhöyük 2009 archive report. Cultural and Environmental Materials Reports, Çatalhöyük, pp 62–73

Russell N, Twiss KC, Orton DC, Demirergi A (2013) More on the Çatalhöyük mammal remains. In: Hodder I (ed) Humans and landscapes of Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons. British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 47, Monumenta Archaeologica 30, Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 213–258

Sezik E, Yeşilada E, Honda G, Takaishi Y, Takeda Y, Tanaka T (2001) Traditional medicine in Turkey X. Folk medicine in central Anatolia. J Ethnopharmacol 75:95–115

Sidorovich V (2009) Guide to mammal and bird activity signs. Zimaletto, Miensk

Skumatov D, Abramov AV, Herrero J, Kitchener A, Maran T, Kranz A, Sándor A, Saveljev A, Savour-Soubelet A, Guinot-Ghestem M, Zuberogoitia I, Birks JDS, Weber A, Melisch R, Ruette S (2016) Mustela putorius. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T41658A45214384.en. Accessed 20 May 2017

Stubbe M (1993a) Martes martes. In: Niethammer J, Krapp F (ed) Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas. Band 5: Raubsäuger: Carnivora (Fissipedia). Teil II: Mustelidae 2, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae. AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 374–427

Stubbe M (1993b) Martes foina. In: Niethammer J, Krapp F (ed) Handbuch der Säugetiere Europas. Band 5: Raubsäuger: Carnivora (Fissipedia). Teil II: Mustelidae 2, Viverridae, Herpestidae, Felidae. AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden, pp 427–481

Sullivan TP, Sullivan DS (1980) The use of weasels for natural control of mouse and vole populations in a coastal coniferous forest. Oecologia 47:125–129

Trolle-Lassen T (1987) Human exploitation of fur animals in Mesolithic Denmark a case study. Archaeozoologica 1:85–102

Türkcan AU (2013) Çatalhöyük stamp seals from 2000-2008. In: Hodder I (ed) Substantive technologies at Çatalhöyük: reports from the 2000-2008 seasons, British Institute at Ankara Monograph No. 48, Monumenta Archaeologica 31. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, Los Angeles, pp 235–246

Val A, Mallye JB (2011) Small carnivore skinning by professionals: skeletal modifications and implications for the European upper Palaeolithic. J Taphon 9:221–243

Vekua A (1994) Die Wirbeltierfauna der Villafranchium von Dmanisi und ihre biostratigraphische Bedeutung. Jahrb Röm-Germ Zent 41:77–180

von den Driesch A (1976) A guide to the measurement of animal bones from archaeological sites. Peabody Museum Press, Harvard

Watson JP (1979) The estimation of the relative frequencies of mammalian species: Khirokitia 1972. J Archaeol Sci 6:127–137

White TE (1953) A method of calculating the dietary percentage of various food animals utilized by aboriginal peoples. Am Antiq 18:396–398

Wood WR, Johnson DL (1978) A survey of disturbance processes in archaeological site formation. In: Schiffer MB (ed) Advances in archaeological method and theory. Academic Press, New York, San Francisco, London, pp 315–381

Yalden DW (1999) The history of British mammals. Poyser, London

Yiğit N, Çolak E, Sözen M, Özkurt Ş (1998) Contribution to the taxonomy, distribution and karyology of Martes foina (Erxleben, 1777) (Mammalia: Carnivora) in Turkey. Turk J Zool 22:297–301

Zhou YB, Newman C, Xu WT, Buesching CD, Zalewski A, Kaneko Y et al (2011) Biogeographical variation in the diet of Holarctic martens (genus Martes, Mammalia: Carnivora: Mustelidae): adaptive foraging in generalists. J Biogeogr 38:137–147

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank those who assisted in the correlation of flotation samples: Marek Z. Barański, Agata Czeszewska, Patrycja Filipowicz, Arkadiusz Klimowicz, and Arkadiusz Marcinik. Additionally, special thanks go to Marek Z. Barański for working on Fig. 3. We are thankful to the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism for permission to carry out the fieldwork.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KP; performed the experiments: KP, AM; analyzed the data: KP; contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: KP, AM; wrote the paper: KP, AM (taxonomic part only); performed the figures: KP (Figs 2, 7, 8, 9, and 10), AM (Figs 1, 4, 5, and 6).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial disclosure

Financial support for the archeological and zooarchaeological work as well as for radiocarbon dating was provided by Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (http://amu.edu.pl) (KP) and the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (http://www.nauka.gov.pl/en/) (0501/B/P01/2010/39) (KP). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Pawłowska, K., Marciszak, A. Small carnivores from a Late Neolithic burial chamber at Çatalhöyük, Turkey: pelts, rituals, and rodents. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 10, 1225–1243 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0526-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-017-0526-1