Abstract

Background

This study aimed to develop an expert consensus regarding the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) in the Middle East.

Methods

A three-step modified Delphi method was utilized to develop the consensus. Fifteen specialized pediatricians participated in the development of this consensus. Each statement was considered a consensus if it achieved an agreement level of ≥ 80%.

Results

The experts agreed that the double-blind placebo-controlled oral challenge test (OCT) should be performed for 2–4 weeks using an amino acid formula (AAF) in formula-fed infants or children with suspected CMPA. Formula-fed infants with confirmed CMPA should be offered a therapeutic formula. The panel stated that an extensively hydrolyzed formula (eHF) is indicated in the absence of red flag signs. At the same time, the AAF is offered for infants with red flag signs, such as severe anaphylactic reactions. The panel agreed that infants on an eHF with resolved symptoms within 2–4 weeks should continue the eHF with particular attention to the growth and nutritional status. On the other hand, an AAF should be considered for infants with persistent symptoms; the AAF should be continued if the symptoms resolve within 2–4 weeks, with particular attention to the growth and nutritional status. In cases with no symptomatic improvements after the introduction of an AAF, other measures should be followed. The panel developed a management algorithm, which achieved an agreement level of 90.9%.

Conclusion

This consensus document combined the best available evidence and clinical experience to optimize the management of CMPA in the Middle East.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is an abnormal immunological response to specific proteins, mainly casein and/or whey proteins, present in either formula or breast milk [1]. The current epidemiological figures highlight that CMPA is the prevalent form of food hypersensitivity in children younger than three years, affecting up to 7.5% of them in the first year of life [2]. In some Middle Eastern countries, the incidence of CMPA among infants younger than 2 years was reported to be 3.4% [3]. Positive family history of atopy and atopic dermatitis in early infancy are distinguished risk factors for CMPA [4, 5]. Based on the type of immunological reactions, the clinical presentation of the CMPA can be broadly divided into immediate and delayed-onset presentations. Eczema and allergic colitis are commonly present in breastfed infants [6].

CMPA is a clinical condition in which proper history taking and physical examination are the cornerstones for accurate identification of the patients [7]. However, the diagnosis of CMPA can be challenging, and further investigations are usually requested [2, 7, 8]. The management of CMPA is usually tailored according to the type of feeding and age of affected patients [8, 9]. Correct identification and management of CMPA are crucial to optimize infant growth and to prevent severe complications.

In the Middle East, it was reported that the practice of exclusive breastfeeding up to 6 months of life is poorly followed [10]. The early introduction of cow's milk can significantly increase the risk of CMPA among infants from the Middle East; in addition, the utilization of other forms of milk, such as goat's milk, is rather common in this region, which may exhibit cross-reactivity with cow's milk [11, 12]. Thus, it is imperative to develop a consensus to aid general practitioners and pediatricians in the diagnosis and management of CMPA in the Middle East region. Although previous consensus documents for the diagnosis and management of CMPA from the Middle East region were published [10, 13], they did not utilize the Delphi-based approach, which offers the advantages of systematic approach and subject anonymity during voting [14].

Thus, we conducted a Delphi method-based study to develop a consensus regarding the epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of CMPA in the Middle East. A three-step Delphi survey was adopted to integrate the opinions of experts and to formulate a clinical pathway algorithm for diagnosis and management of CMPA that presents to primary and advanced healthcare settings in the Middle East. Moreover, we aimed to record the unmet medical needs concerning CMPA management.

Methods

Study design

A three-step modified Delphi method was utilized to develop the present consensus through the period from September to December 2020. This study consisted of two rounds of an anonymous voting and a virtual expert discussion meeting to develop the consensus statements and the clinical pathway algorithm.

Expert panel recruitment

A non-probability purposive sampling technique was conducted to recruit 15 specialized pediatricians from the following countries: Egypt, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Lebanon, Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. All experts were required to have an active research profile in the field of pediatric immunology and gastroenterology, and to be affiliated with an academic institution from the Middle East region. Eligible experts were invited via email to participate and were asked to participate in the three steps of the Delphi method-based study.

Survey development

A systematic literature search was employed on Medline via PubMed from its inception to September 2020 to collect relevant information by the survey development committee. Various combinations of the following keywords were used to identify potentially eligible literature: ("Cow's milk protein allergy" OR "allergy, milk[MeSH Terms]" OR "(allergies, milk[MeSH Terms])") and ("epidemiology" OR "incidence" OR "features" OR "diagnosis" OR "diagnostic tests" OR "Skin prick test" OR "Serum Ig-E" OR "Food challenge" OR "elimination diet" OR "prevention" OR "Management" OR "Extensively hydrolyzed formula" OR "Amino acid–based formula" OR "Formula"). The statements were primarily extracted from studies with level 1 quality of evidence, as classified by Wright et al.[15]. Additional statements were retrieved from studies with a lower quality of evidence whenever deemed required by the survey development committee. All statements were collected in an Excel spreadsheet, and the committee held a meeting to finalize the draft consensus statements.

Voting rounds

The development of the consensus document passed through three steps. In the first step, a draft questionnaire was sent to experts via email. The questionnaire consisted of binary statements for which the experts were asked to choose between “agree” and “disagree” options. Each expert was able to comment on each statement and to provide suggestions. Each statement was considered a consensus if it achieved an agreement level of ≥80% [16]. The statements that did not achieve the agreement level were persevered for step 2 to be modified or omitted by the experts. A virtual advisory board meeting was conducted in the second step and engaged all experts on the 30th of October 2020. The meeting was divided into two parts. In the first part, the statements that achieved ≥80% agreement were presented for full consensus by the panel, while the remaining statements were presented for modification or omission. The second part of the meeting aimed to develop the clinical pathway algorithm for patients presenting with CMPA. In the final step, the list of modified statements and the clinical pathway algorithm were emailed to the experts for voting and followed the same voting process of step 1.

Results and discussion

Epidemiology

CMPA is the most prevalent food allergy (FA) of young children [17]. In infants less than one year of age, two cohort studies showed that the prevalence of CMPA ranged between 2.2 and 2.8%, which is consistent with the findings of another cohort of approximately 6000 newborns followed for 34 months [18, 19]. Many systematic reviews and meta-analyses were conducted to assess the prevalence of CMPA globally. Rona et al. conducted a pooling analysis of 51 studies to assess the worldwide prevalence of FA [17]. Their findings showed that the prevalence of self-reported CMPA ranged between 1.2 and 17%. This estimate was significantly lower in the studies that reported their prevalence based on symptomatic evaluation (0–2%), food challenge (0–3%), and skin prick test (SPT) sensitization and IgE assessment (2–9%). In the meta-analysis of Nwaru et al. [20], the overall effect estimate of 42 primary articles on CMPA demonstrated that the prevalence of self-reported CMPA was 2.3% (95% CI 2.1–2.5), food challenge was 0.6% (95% CI 0.5–0.8), SPT alone was 0.3% (95% CI 0.03–0.6), and by sIgE alone, it was 4.7% (95% CI 4.2–5.1). A higher prevalence has been shown among younger ages. Both studies concluded that the observed variation is attributed to the varying factors including the study design, source of population, age of participants, geographical region, and diagnosis limitations.

In the Middle East, Katz et al. conducted a single-center prospective study, which identified that the cumulative incidence of CMPA over 2 years of follow-up was 0.5% in Israeli infants. They also showed that the mean age of onset was 4 months [21]. In Oman, sensitization to cow milk was reported in 78/164 patients. This prevalence may be overestimated owing to the small sample size and the diagnostic test used [22]. In Kuwait, a survey of self-reported FA showed that out of 865 participants, 104 reported FA. Of them, 46.7% had CMPA. The prevalence in early childhood was 21.9%, and in late childhood, it was 20.8% [23]. In Lebanon, the prevalence of self-reported CMPA was 14%. It ranked as the fourth common allergen [24]. Zeyrek et al., reported that the prevalence of CMPA was 0.16% in children under 2 years of age in Turkey [25].

The experts stated that the estimated prevalence of CMPA in the Middle East ranges from 1 to 5% (level of agreement = 86.7%, Table 1).

Diagnosis

For CMPA, there is no single test or biomarker that is pathognomonic of the condition [8]. The cornerstones of the CMPA diagnosis are the reliable history and the proper physical examination [26]. A systematic approach is required for an accurate diagnosis and should begin with an allergy-focused history and physical examination. Many differential diagnoses should be considered, including immune deficiency, gastroesophageal reflux disease, infective colitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis [27]. In the case of non-definitive diagnosis, empirical exclusion therapy is not an evidence-based practice and should be avoided.

Clinical presentations of CMPA

Clinical features of CMPA are usually present within a few days or months of life after the introduction of a cow's milk-based formula. Moreover, the same symptoms can occur if the cow’s milk protein (CMP) is transmitted from the maternal diet to the infant through maternal breast milk [28]. Several IgE- and non-IgE-mediated clinical syndromes are found to be associated with CMPA patients. In patients with IgE-mediated, the most common clinical presentations are urticaria, anaphylaxis, angioedema, oropharyngeal or gastrointestinal reactions, and food-associated anaphylaxis [29]. In patients with non-IgE-mediated CMPA, gastrointestinal reflux, colic, constipation, food protein-induced enteropathy are frequent [30]. Atopic dermatitis and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are seen in patients with mixed IgE and non-IgE-mediated CMPA [31].

Investigations

Oral food challenge (OFC)

Diagnostic approaches of CMPA are limited and affect the ability to explain the underlying epidemiology. A double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenge (DBPCFC) is the gold standard and the most specific test for diagnosis [26]. In young children, open OFC is well-validated with some concerns. Clinical allergy and sensitization can be differentiated using OFC [32]. Nevertheless, DBPCFC and OFC require a longer time to perform and should be done under medical observation as they are associated with a risk of anaphylaxis [33]. Therefore, the OFCs are not always ideal for clinical practice. A therapeutic elimination diet should be applied immediately in cases of severe anaphylaxis. After the elimination period, the test should be repeated to confirm the tolerance development [34]. Using OFC, CMPA can be ruled out if the patient remains without symptoms for 2 weeks [35]. Nevertheless, the diagnosis of CMPA is proven if the symptoms arise.

Serum-specific IgE and skin prick test (SPT)

Studies using these approaches may have inadequate evaluations of extremely atopic children owing to parental refusal and safety issues. In both epidemiological and therapeutic trials, targets include serum-specific IgE and SPT [27]. The presence of IgE tissue-bound antibodies and circulating antibodies is detected by SPT and specific IgE (sIgE), respectively [36]. These two measures estimate the probability of reaction but are not diagnostically sufficient alone. The SPT-measured sensitization is also described as at least 3 mm wheel larger than the negative control [37]. IgE binding to specific proteins is calculated by cow's milk-specific IgE, measured by in vitro immunoassay; sensitization is characterized as measurable specific IgE (often sIgE is ≥ 0.35 kU/L, sometimes ≥ 0.10 kU/L) [38]. However, positive IgE neither confirms any allergy nor distinguishes sensitization from clinical allergy [8, 28].

In the diagnosis of non-IgE-mediated CMPA, specific IgE tests are not useful [39]. In terms of SPT, a positive test does not confirm an allergy, especially in infants. Moreover, in non-IgE-mediated CMPA, SPT may lead to false-positive or false-negative diagnosis [40]. A definitive diagnosis of IgE-mediated CMPA is confirmed by the history of an instant reaction with classic allergic symptoms and positive sIgE or SPT tests [41]. CMPA self-reporting and sensitization based only on serum IgE and SPT to detect CMPA seems to overestimate the prevalence [17]. Furthermore, differences in the sIgE tests may result in conflicting interpretations and may restrict comparability.

Endoscopy and biopsy

In infants, CMPA can result in occult blood in stools, which can be detected until 6–12 weeks after avoidance of CMP. After 3 weeks, sigmoidoscopy is indicated if the occult blood is still detected [2]. Other indications for upper and lower endoscopy include persistent malabsorption or malnutrition, nutrient deficiency, inadequate weight gain, malnutrition, persistent anemia, suspected eosinophilic gastroenteropathy or eosinophilic esophagitis, persistent abdominal pain and bloating, hyporexia, and suspected inflammatory bowel disease [42]. CMPA cases may exhibit signs suggestive of eosinophilic esophagitis in the endoscopic examination, such as circular rings and altered vascular patterns. In patients with initial presentation of persistent vomiting, upper endoscopy may be suggested to exclude surgical cases or eosinophilic gastroenteritis. In patients with CMPA accompanied with gastrointestinal manifestations, both sigmoidoscopy and rectal biopsy were reported to be predictive [43]. In the majority of the patients, the histological examination may reveal focal erythema or nodular lymphoid hyperplasia [44]. CMPA is confirmed in the existence of more than 15–20 eosinophils per high power field or more than 60 eosinophils in six high power fields [27].

Scoring system for screening

There are many scoring systems for the CMPA; however, Cow’s milk-related symptom score (CoMiSS), a simple, fast, and easy-to-use awareness tool, is the most common [26]. However, until now, there is no consensus on the cut-off values for this tool. Besides this, the sensitivity and specificity of the CoMiSS tool are poor. Therefore, it cannot be recommended as a screening tool until more studies are available.

Diagnostic elimination

In exclusively breastfed infants, CMPA is typically mild and not associated with failure to thrive or anemia [45]. It is recommended to advise the mother to avoid consumption of dairy products and/or bovine milk in the first 6 months. Moreover, mothers should avoid dairy or milk-containing foods in their diet [46]. In response to the elimination of milk and its products, the antigens may disappear within 72 hours from the mother’s breast milk. Following the elimination, if the symptoms improved, it is recommended to re-introduce the suspected allergen to the mother’s diet in the case of a breastfed infant or to re-introduce the previously used formula [41]. The recurrence of symptoms can confirm the diagnosis of CMPA and should be followed by eliminating the allergen and continuous breastfeeding. However, if the previous reaction is severe or life-threatening, this circulation should be omitted until the reaction is consistent or the patient is transferred to an experienced center. The elimination diet should be maintained for at least six months or until 12 months of age [47]. However, in patients with IgE-mediated CMPA, an elimination diet should be maintained for 18 months. In formula-fed cases, the recommended formulas are extensively hydrolyzed formula (eHF), or an AAF in case of severe symptoms [26]. During the diagnostic elimination period, cow’s-milk and cow’s-milk-containing formula and supplementary foods should be strictly forbidden in non-breastfed infants [48]. If the first feed in a formula-fed baby causes signs of CMPA, the formula should be modified, and the elimination should be made in the infant's diet, not in the mother's diet [26].

Many hidden allergens can cause CMPA; therefore, the counseling of an experienced, clinically trained pediatric dietitian is strongly recommended. For children over two years with persistent severe CMPA, solid foods and liquids free of cow’s milk protein should be given unless the child has multiple allergies [8]. Besides these interventions, goat's and sheep's-milk protein should be strictly avoided due to the high cross-reactivity with cow’s milk protein [49]. In cases of highly atopic children or children with eosinophilic digestive tract disorders, if multiple FA is suspected, an exclusive feeding with an AAF may be considered to improve the symptoms before an oral challenge with cow’s milk is performed [48, 50].

The statements regarding the epidemiology and diagnosis of CMPA that achieved a consensus agreement are provided in Table 1. The panel emphasized the importance of early diagnosis and exclusive or partial breastfeeding. The panel agreed that infants with a positive family history of atopy in first-degree relatives are at increased risk of CMPA. Despite the significant impact of early diagnosis on the outcome of CMPA, the experts stated there is an apparent delay in the diagnosis of CMPA in the Middle East, which can be extended up to 6 months. Infants with positive family history, who exhibit allergic symptoms after the introduction of cow’s milk involving at least two systems and not responding to treatment, should be suspected for CMPA. Dermatological and gastrointestinal manifestations commonly present in CMPA, while respiratory manifestations occur in less than one-fourth of the patients. However, general pediatricians and primary healthcare physicians should be aware that unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms may be the only presentation of FA.

Although the experts stated that the CMPA is a clinical diagnosis, they highlighted that a number of available tests could add diagnostic and prognostic values, including specific IgE levels and SPT in infants older than 6 months. However, in highly atopic infants, intradermal testing should not be performed. The existence of persistent or severe unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms is an indication for endoscopy with biopsies if it co-exists with failure to thrive or refractory iron-deficiency anemia.

The diagnostic elimination diet should be continued for 2–4 weeks and should be deprived of CMP or other unmodified animal milk proteins; nonetheless, the confirmatory CMP challenge can be postponed in highly sensitized infants until the child shows reduced levels of specific IgE. In case of persistent or severe symptoms, an AAF should be tried for a maximum of 2 weeks before CMPA is ruled out. Additional indications for an AAF are when the child refuses the taste of the eHF or when the cost–benefit ratio favors the use of an AAF.

During an elimination diet, mothers of exclusively breastfed infants should continue breastfeeding while maintaining a restricted diet. However, in rare cases, if breastfed infants with severe symptoms did not improve after maternal diet elimination, a trial of AAF is recommended for a period of several days to a maximum of 2 weeks.

In addition, the experts agreed that the starting dose during an oral milk challenge in children with a delayed reaction should be increased stepwise to 100 mL. If severe reactions are expected, the challenge should begin with minimal volumes.

Management of at-risk infants and the role of hydrolyzed formulas

Untreated CMPA can increase the risk of allergic disorders later in life [51]. The timing of the development of CMPA is a major determinant of growth retardation, with earlier CMPA development carrying a greater risk of growth retardation [7]. CMPA also can adversely affect the quality of life of infants and their families [52]. Thus, the identification and monitoring of at-risk patients are crucial to optimize the outcomes of CMPA. Several risk factors are incorporated in the development of CMPA, including a positive family history of atopy, prematurity, multi-parity, advanced maternal age, mother's education, formula feeding, and short time of exclusive breastfeeding [10, 53].

Exclusive breastfeeding for 4–6 months is a widely recommended, cost-effective, strategy for at-risk infants. Previous reports showed that exclusive breastfeeding was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of cow's milk sensitization and atopic dermatitis [54,55,56]. Nonetheless, the current body of evidence still shows conflicting results regarding the beneficial role of exclusive breastfeeding in preventing FA [57, 58]. According to the recent European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), there is no recommendation for or against using breastfeeding to prevent FA; nonetheless, exclusive breastfeeding should be universally recommended owing to its outstanding benefits for both mother and infant [59].

On the other hand, modification of maternal diet is not recommended as a general preventive strategy for FA [29]; the current body of evidence demonstrates a negative impact of diet restriction on maternal and fetal weight [60]. Nonetheless, previous systematic reviews have highlighted that an antigen avoidance diet can reduce the risk of allergic diseases in at-risk infants; however, these findings should be interpreted cautiously owing to the low quality of supporting evidence [60]. Nonetheless, a recent review concluded that avoiding potential food allergens may have little to no effect on the risk of CMPA [59].

In formula-fed infants with a high risk of CMPA, usually defined as a positive family history of atopy among first-degree relatives, it was previously thought that CMP should be avoided in the diets (by using hydrolyzed formula) to prevent CMPA development [10]. According to recent EAACI guideline, the introducing CMP-based formula after the first week of life did not have a consistent impact on the development of CMPA in infancy or early childhood, with no significant harms after three months of age [59].

Hydrolyzed formulas are manufactured by variable degrees of hydrolysis of milk protein to smaller peptides. By exposing the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) to such small peptides, hydrolyzed formulas can induce oral tolerance without sensitization, with a subsequent decrease in the risk of atopic diseases [61]. According to the degree of hydrolysis, these formulas are classified into partially hydrolyzed formulas (pHF; peptides size < 5 kDa) or eHF (peptides size < 3 kDa) [62]. The eHF is characterized by minimum allergenicity and, hence, is more preferred during the treatment of CMPA. On the other hand, pHF is theoretically associated with more immunogenicity and can lead to greater induction of oral tolerance than eHF [63, 64]. In addition, pHF is thought to be easily digested and has the advantages of better gastrointestinal tolerance than cow's milk formula (CMF) or other standard formulas [65]. Several randomized controlled trials showed no significant difference in atopic dermatitis incidence between different hydrolyzed formulas or between hydrolyzed formulas and CMF [61, 66, 67]. According to the recent EAACI guideline, pHF or eHF, whey or casein, may not reduce the risk of CMPA compared with conventional CMF [59]. Therefore, no recommendation exists for or against using pHF or eHF to prevent CMPA in infants. When exclusive breastfeeding is not possible, many substitutes are available to utilize, including hydrolyzed formulas. The EAACI also recommended that supplementation with regular cow's milk formula may be avoided in the first week of life.

In a small set of infants, hydrolyzed formulas can trigger immunological reactions due to residual proteins. In these conditions, the AFF has been proposed as an alternative formula to avoid hypersensitivity [68, 69]. However, there are no data to support its use for preventing allergic diseases in at-risk infants [13].

The current body of evidence demonstrated substantial heterogeneity in the benefits of diet restriction and timing of introduction of solid food on the outcomes of CMPA among at-risk infants [70,71,72]. Delayed introduction of the food can lead to nutritional imbalance and growth deficits [29]. Thus, the previous consensus from the Middle East did not recommend delayed introduction of solid food beyond the first 4–6 months of life [13].

The intestinal microbiome is an integral part of the development process during the first year of life. Previous studies have established a strong association between microbiome dysfunction and the development of allergic diseases [73, 74]. Thus, a growing number of literature evaluated the role of prebiotics-rich formulas and probiotic supplements during pregnancy on the incidence of FA among at-risk infants [75, 76]. Hypothetically, prebiotics can selectively induce the growth of a beneficial gut microbiome, with a subsequent reduction in the risk of eczema and other allergic diseases [73]. Concerning the availability of clinical evidence, previous consensuses highlighted that no data exist to support the use or avoidance of prebiotic supplements during pregnancy and lactation [77]. In exclusively breastfed infants, the prebiotics did not exhibit clear benefits concerning the prevention of allergic diseases [78].

Management of CMPA

Early diagnosis is a major determinant of the course of CMPA. A delay in the diagnosis of CMPA significantly increases the risk of growth retardation, anemia, and hypoproteinemia [79]. In both formula and breastfed infants, strict avoidance of a CMP-containing diet is the cornerstone for the management of CMPA [80]. The management is then tailored according to the age of the patients, type of feeding, type of hypersensitivity reactions, and the severity of clinical symptoms [69].

It is universally recommended to breastfeed infants with CMPA [13]. In exclusively breastfed infants, mothers are instructed to avoid any CMP-containing diet, such as cow’s milk products including cheese and yogurt, due to the excretion of cow's milk peptides in breast milk [81]. If the CMP-containing diet is prolonged, it should be accompanied by nutritional counseling to assess the mother's needs for dietary supplements to replenish micronutrients (e.g., calcium, vitamin D) and energy deficiency [55]. The diet elimination is usually recommended for 2–4 weeks, followed by symptomatic assessment. In case of no symptoms, CMP can be re-introduced, and the infants should be observed closely for symptomatic relapse. A mother of relapsed infants should continue the diet elimination as long as she is breastfeeding [79].

When exclusive breastfeeding is impossible, a "therapeutic formula" is the first-line management option for infants with mild-to-moderate symptoms. This formula is generally characterized by minimal amounts of CMP, in the form of eHF, or complete deprivation of CMP, such as an AAF [63, 64]. While many factors can govern the choice of suitable therapeutic formula, such as cost, palatability, and availability [82], the eHF is well-tolerated by the majority of formula-fed infants, and it has been advocated as the formula of choice by the European and Middle Eastern guidelines [8, 13]. As mentioned previously, it is rather common in the Middle East to utilize other forms of milk, such as goat's milk, which may exhibit cross-reactivity with cow's milk. Thus, primary care physicians and general pediatricians should be aware of other types of milk or diet with cross-reactivity to cow's milk [13]. On the other hand, the pHF is not recommended by many international guidelines for the treatment of CMPA [55, 83].

AAF is primarily reserved for infants exhibiting reactivity to eHF, nearly 2–10% and 40% of uncomplicated and complicated CMPA, respectively [84]. Intolerance to eHF can lead to persistent symptoms, severe complications, delayed diagnosis, and excessive healthcare expenditure [85]. According to the ESPGHAN guideline, the AAF is indicated in cases with severe symptoms, such as anaphylaxis [8]. While the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology (BSACI) defined the criteria for AAF use as eHF intolerance, severe symptoms, enteropathies, severe non-IgE-mediated diseases, faltering growth, multiple food allergies, and exclusively breastfed infants with allergic symptoms or severe atopic eczema [28].

Alongside eHF and AAF, other formulas are available as alternatives or to fulfill the nutritional requirements of specific subpopulations. For example, a nutritionally complete formula with its fat source being predominantly medium chain triglycerides (MCT) can be used in infants with malabsorptive enteropathy to ensure adequate fat absorption and energy intake [86]. The use of soy-based formula is common in some regions [13]. Soy-based formula is thought to reduce the incidence of allergic disorders compared to other CMP-based formulas [87, 88]. Besides, the cost of soy-based formula is lower than the eHF and, the former is regarded to be more palatable [89]. Recent evidence also has highlighted that soy-based formula did not exhibit adverse effects on the growth and physiological functions of the infants [90]. However, cross-reactivity between soy and CMP has been reported, and nearly 10–15% of the infants aged less than 6 months may be sensitized to soy [13]. In addition, there are concerns regarding the harmful impacts of phytoestrogens content of the soy-based formula on the sexual and endocrine development of the infants, although the current evidence is doubtful [91]. Also, the eHF leads to greater oral tolerance towards CMP than soy-based formula. Thus, the soy-based formula can be considered in infants older than six months in cases of unaffordable eHF or when infants rejected the taste of eHF [92].

Rice-based formula is another CMP-free alternative, with the advantage of affordable cost, good palatability, and nutritional adequacy [93, 94]. However, rice-based formula is available in limited centers within the Middle East, and there is no strong evidence to support the use of rice-based formula, owing to limited data regarding its efficacy and concerns over the arsenic levels [13, 95].

Weaning of infants with confirmed CMPA should be based on a CMP-free diet until a challenge test confirms the tolerance acquisition. However, it is critical to emphasize the importance of not delaying supplementary foods and the gradual introduction of these foods, preferably while the mother is still breastfeeding. Nutritional supervision is crucial during the weaning until CMP-containing food is introduced [55]. New methods of weaning are evolving, such as spoonable yogurt-consistency or semi-solid AAF formula to enhance energy intake, nutritional intake (especially calcium), and tolerability, which was found to be comparable to AAF in children above 6 months of age [96].

Nearly half of the infants with CMPA tolerate CMP by the first year of life; this percentage increases to 75% by the end of the third year of life [89]. Previous guidelines and consensus documents recommended that the eHF should be continued for at least 6 months, alongside nutritional counseling, before re-challenging [55, 82]. However, infants with severe IgE-mediated reactions or high IgE titer usually stay on the eHF for a longer duration (up to 18 months) [8, 29]. A challenge with cow's milk may be performed after maintaining a therapeutic diet for at least three months in a specific IgE negative test or mild symptoms, and at least 12 months in a high-positive IgE test or severe reaction [13]. A recent consensus from the Middle East has proposed a step-down approach in which the pHF-whey (pHF-W) can be used as a bridge between therapeutic formulas and intact CMP in the challenge test. The proposed benefits of this approach include a decrease in the misuse of pHF in the treatment of CMPA and proper management of functional gastrointestinal disorders [10]. Nonetheless, this approach is still not supported by solid clinical evidence, and further trials are required to assess its clinical benefits.

The addition of prebiotics and synbiotics to therapeutic formulas was found to improve tolerance rate at the end of the first year of life [97, 98]. Among infants with non-IgE-mediated reaction, the combination of AAF and synbiotics resulted in improved gut microbiota comparable to that of healthy infants [97].

The statements regarding the management of CMPA that achieved a consensus agreement are provided in Table 2. The panel emphasized the importance of early diagnosis and exclusive or partial breastfeeding. In formula-fed infants, eHF is the first option, while AAF is preserved for infants with red flag signs or reactions to eHF. Therapeutic formula containing MCT is recommended for infants with CMPA and with malabsorptive enteropathy. The CMP re-challenge should be pursued only after a minimum of 6 months for confirmed cases, and this period should be extended to 12–18 months in cases with severe immediate IgE-mediated reactions. The use of AAF with specific synbiotics is recommended.

Management algorithm

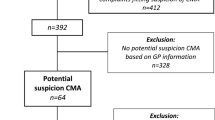

The panel agreed that in formula-fed infants or children with suspected CMPA, the DBPCFC should be performed for 2–4 weeks using AAF. Formula-fed infants with confirmed CMPA should be offered a therapeutic formula. The eHF with MCT is indicated with no red flag signs. At the same time, the AAF is offered for infants with red flag signs (severe anaphylactic reactions, severe gastrointestinal symptoms, severe eczema, faltering growth, and multiple food allergies). Infants on eHF, who exhibit resolution of symptoms within 2–4 weeks, should continue eHF, with special attention to the growth and nutritional status. On the other hand, AAF should be considered for infants with persistent symptoms. In infants with red flag signs, who are offered AAF, the AAF should be continued if the symptoms resolve within 2–4 weeks, with particular attention to the growth and nutritional status. In contrast, in cases with no symptomatic improvements after AAF, other measures should be followed, including the exclusion of CMPA, a repeat of unrestricted diet, or referral to a specialized center. This algorithm achieved an agreement level of 90.9% (Fig. 1).

Strengths and limitations

Previously, it was suggested that a minimum of 12 experts was required to ensure the reliability of the Delphi-based consensus [99]. The present survey successfully recruited 15 experts from various Middle East countries, which improved the validity of the final consensus statement. We also utilized a purposive sampling technique to ensure adequate group dynamics during the virtual meeting [100]. The high response rates during each step of the Delphi process was another strength. However, the current process has certain limitations. Although incorporating the virtual meeting in the Delphi process allowed more feedback from the expert and exchange of information, it might have impacted the subject's anonymity and led to the "dominant individuals" effect [14]. Some statements were not supported by level 1 evidence, representing another limitation of the present consensus. The possibility of selection bias during the panel recruitment phase was present as well.

Conclusions

The estimated prevalence of CMPA in the Middle East ranges from 1 to 5%. The present Delphi-based study combined the best available evidence and clinical experience to optimize the diagnosis and management of CMPA presenting to the healthcare settings in the Middle East. The experts developed several statements and a clinical pathway algorithm to aid primary healthcare physicians and general pediatricians in diagnosis and management of CMPA presenting to primary and advanced healthcare settings in the Middle East. Multidisciplinary collaboration is needed to develop regional consensus regarding the diagnosis and treatment of CMPA in infants and children. The consensus should be comprehensive and should involve all specialties and key players that deal with CMPA to share their ideas and suggestions. Another interesting idea is to develop a national day for CMPA in which experts get together and hence move forward.

Data availability statement

Not applicable.

References

Fiocchi A, Schünemann HJ, Brozek J, Restani P, Beyer K, Troncone R, et al. Diagnosis and rationale for action against cow’s milk allergy (DRACMA): a summary report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:1119–28.

Mousan G, Kamat D. Cow’s milk protein allergy. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;55:1054–63.

Maksoud HMA, Al-Seheimy LA, Hassan KA, Salem M, Elmahdy EA. Frequency of cow milk protein allergy in children during the first 2 years of life in Damietta Governorate. Al-Azhar Assiut Med J Medknow. 2019;17:86.

Hill DJ, Hosking CS. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis in infancy: an epidemiologic study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2004;15:421–7.

Hill DJ, Hosking CS, De Benedictis FM, Oranje AP, Diepgen TL, Bauchau V, et al. Confirmation of the association between high levels of immunoglobulin E food sensitization and eczema in infancy: an international study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:161–8.

Host A, Halken S. Cow’s milk allergy: where have we come from and where are we going? Endocr Metab Immune Disord Targets. 2014;14:2–8.

Vandenplas Y, Brueton M, Dupont C, Hill D, Isolauri E, Koletzko S, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. Arch Dis Child. 2007;92:902–8.

Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow’s-milk protein allergy in infants and children: Espghan gi committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:221–9.

Dupont C, Chouraqui JP, De Boissieu D, Bocquet A, Bresson JL, Briend A, et al. Dietary treatment of cows’ milk protein allergy in childhood: a commentary by the Committee on Nutrition of the French Society of Paediatrics. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:325–38.

Vandenplas Y, Al-Hussaini B, Al-Mannaei K, Al-Sunaid A, Helmi-Ayesh W, El-Degeir M, et al. Prevention of allergic sensitization and treatment of cow’s milk protein allergy in early life: the middle-east step-down consensus. Nutrients. 2019;11:1444.

Restani P, Beretta B, Fiocchi A, Ballabio C, Galli CL. Cross-reactivity between mammalian proteins. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:11–5.

Sheehan WJ, Gardynski A, Phipatanakul W. Skin testing with water buffalo’s milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. Pediatr Asthma Allergy Immunol. 2009;22:121–5.

Vandenplas Y, Abuabat A, Al-Hammadi S, Aly GS, Miqdady MS, Shaaban SY, et al. Middle east consensus statement on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of cow’s milk protein allergy. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2014;17:61–73.

Eubank BH, Mohtadi NG, Lafave MR, Wiley JP, Bois AJ, Boorman RS, et al. Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:56.

Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Jt Surg Ser A. 2003;85:1–3.

Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986;35:382–6.

Rona RJ, Keil T, Summers C, Gislason D, Zuidmeer L, Sodergren E, et al. The prevalence of food allergy: a meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol US. 2007;120:638–46.

Hill DJ, Hosking CS, Heine RG. Clinical spectrum of food allergy in children in Australia and South-East Asia: identification and targets for treatment. Ann Med Engl. 1999;31:272–81.

Schrander JJ, van den Bogart JP, Forget PP, Schrander-Stumpel CT, Kuijten RH, Kester AD. Cow’s milk protein intolerance in infants under 1 year of age: a prospective epidemiological study. Eur J Pediatr Germany. 1993;152:640–4.

Nwaru BI, Hickstein L, Panesar SS, Roberts G, Muraro A, Sheikh A. Prevalence of common food allergies in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy Denmark. 2014;69:992–1007.

Katz Y, Rajuan N, Goldberg MR, Eisenberg E, Heyman E, Cohen A, et al. Early exposure to cow’s milk protein is protective against IgE-mediated cow’s milk protein allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol US. 2010;126:77-82.e1.

Al-Tamemi S, Naseem SUR, Tufail-Alrahman M, Al-Kindi M, Alshekaili J. Food allergen sensitisation patterns in omani patients with allergic manifestations. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:e483–8.

Ali F. A survey of self-reported food allergy and food-related anaphylaxis among young adult students at Kuwait University, Kuwait. Med Princ Pract Int J Kuwait Univ Heal Sci Cent. 2017;26:229–34.

Irani C, Maalouly G. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy in Lebanon: a middle-eastern taste. Int Sch Res Not. 2015;2015:639796.

Zeyrek D, Koruk I, Kara B, Demir C, Cakmak A. Prevalence of IgE mediated cow’s milk and egg allergy in children under 2 years of age in Sanliurfa, Turkey: the city that isn’t almost allergic to cow’s milk. Minerva Pediatr Italy. 2015;67:465–72.

Vandenplas Y, Al-Hussaini B, Al-Mannaei K, Al-Sunaid A, Ayesh WH, El-Degeir M, et al. Prevention of allergic sensitization and treatment of cow’s milk protein allergy in early life: the middle-east step-down consensus. Nutrients. 2019;11:1444.

Centre MM, Nadu T, Kamoti K, Trust C, Nadu T, Pradesh U, et al. Guidelines on diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy. 2020.

Luyt D, Ball H, Makwana N, Green MR, Bravin K, Nasser SM, et al. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of cow’s milk allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:642–72.

Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: Report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126.

Gupta RS, Dyer AA, Jain N, Greenhawt MJ. Childhood food allergies: current diagnosis, treatment, and management strategies. Mayo Clin Proc Engl. 2013;88:512–26.

Campbell RL, Hagan JB, Manivannan V, Decker WW, Kanthala AR, Bellolio MF, et al. Evaluation of national institute of allergy and infectious diseases/food allergy and anaphylaxis network criteria for the diagnosis of anaphylaxis in emergency department patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol US. 2012;129:748–52.

Nicolaou N, Poorafshar M, Murray C, Simpson A, Winell H, Kerry G, et al. Allergy or tolerance in children sensitized to peanut: prevalence and differentiation using component-resolved diagnostics. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:191-7.e1.

Kowalski ML, Ansotegui I, Aberer W, Al-ahmad M, Akdis M, Ballmer-weber BK, et al. Risk and safety requirements for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in allergology: World Allergy Organization Statement. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:1–42.

Yue D, Ciccolini A, Avilla E, Waserman S. Food allergy and anaphylaxis. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:111–20.

Zeng Y, Zhang J, Dong G, Liu P, Xiao F, Li W, et al. Assessment of Cow’s milk-related symptom scores in early identification of cow’s milk protein allergy in Chinese infants. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:191.

Wachholz PA, Dearman RJ, Kimber I. Detection of allergen-specific IgE antibody responses. J Immunotoxicol. 2005;1:189–99.

Sicherer S. The diagnosis of food allergy. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010;24:439–43.

Flom JD, Sicherer SH. Epidemiology of cow’s milk allergy. Nutrients. 2019;11:1051.

Venter C, Brown T, Shah N, Walsh J, Fox AT. Diagnosis and management of non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy in infancy—a UK primary care practical guide. Clin Transl Allergy. 2013;3:23.

Maksoud HM, Al Seheimy LA, Hassan KA, Salem M, Elmahdy EA. Frequency of cow milk protein allergy in children during the first 2 years of life in Damietta Governorate. Al-Azhar Assiut Med J. 2019;17:86–95.

Brill H. Approach to milk protein allergy in infants. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1258–64.

María Catalina Bagés M, Carlos Fernando Chinchilla M, Catalina Ortiz P, Clara Eugenia Plata G, Enilda Martha Puello M, Óscar Javier Quintero H, et al. Expert recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of cow’s milk protein allergy in the Colombian pediatric population. Rev Colomb Gastroenterol [Internet]. Asociacion Colombiana de Gastroenterologia; 2020;35:54–64. Available from: https://revistagastrocol.com/index.php/rcg/article/view/405. Accessed 13 Sep 2021.

Poddar U, Yachha SK, Krishnani N, Srivastava A. Cow’s milk protein allergy: an entity for recognition in developing countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:178–82.

Tătăranu E, Diaconescu S, Ivănescu CG, Sârbu I, Stamatin M. Clinical, immunological and pathological profile of infants suffering from cow’s milk protein allergy. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:1031–5.

Lai F, Yang Y. The prevalence and characteristics of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants and young children with iron deficiency anemia. Pediatr Neonatol. 2018;59:48–52.

World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. World Health Organization 2009. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44117.

Mazigh S, Yahiaoui S, Ben Rabeh R, Fetni I, Sammoud A. Diagnosis and management of cow’s protein milk allergy in infant. Tunis Med. 2015;93:205–11.

Sackesen C, Altintas DU, Bingol A, Bingol G, Buyuktiryaki B, Demir E, et al. Current trends in tolerance induction in cow’s milk allergy: from passive to proactive strategies. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:372.

Rodríguez-del-Rio P, Sánchez-García S, Escudero C, Pastor-Vargas C, Hernández J, Pérez-Rangel I, et al. Allergy to goat’s and sheep’s milk in a population of cow’s milk-allergic children treated with oral immunotherapy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:128–32.

Berni Canani R, Ruotolo S, Discepolo V, Troncone R. The diagnosis of food allergy in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:584–9.

Kjaer HF, Eller E, Andersen KE, Høst A, Bindslev-Jensen C. The association between early sensitization patterns and subsequent allergic disease. The DARC birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20:726–34.

Warren CM, Gupta RS, Sohn MW, Oh EH, Lal N, Garfield CF, et al. Differences in empowerment and quality of life among parents of children with food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:117-125.e3.

Sardecka I, Los-Rycharska E, Ludwig H, Gawryjołek J, Krogulska A. Early risk factors for cow’s milk allergy in children in the first year of life. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2018;39:e44-54.

Yang YW, Tsai CL, Lu CY. Exclusive breastfeeding and incident atopic dermatitis in childhood: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:373–83.

Kansu A, Yüce A, Dalgıç B, Şekerel E, Çullu-Çokuğraş F, Çokuğraş H. Consensus statement on diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of cow’s milk protein allergy among infants and children in Turkey Consensus Statement. Turk J Pediatr. 2016.

Liao SL, Lai SH, Yeh KW, Huang YL, Yao TC, Tsai MH, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding is associated with reduced cow’s milk sensitization in early childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:456–61.

Saarinen KM, Juntunen-Backman K, Järvenpää AL, Kuitunen P, Lope L, Renlund M, et al. Supplementary feeding in maternity hospitals and the risk of cow’s milk allergy: a prospective study of 6209 infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:457–61.

Kim J, Chang E, Han Y, Ahn K, Lee S II. The incidence and risk factors of immediate type food allergy during the first year of life in Korean infants: a birth cohort study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2011;22:715–9.

Halken S, Muraro A, de Silva D, Khaleva E, Angier E, Arasi S, et al. EAACI guideline: preventing the development of food allergy in infants and young children (2020 update). Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32:843–58.

Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child. Evid-Based Child Heal. 2014;9:447–83.

Cabana MD. The role of hydrolyzed formula in allergy prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2017;70:38–45.

Nutten S. Proteins, peptides and amino acids: role in infant nutrition. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2016;86:1–10.

Pecquet S, Bovetto L, Maynard F, Fritsché R. Peptides obtained by tryptic hydrolysis of bovine β-lactoglobulin induce specific oral tolerance in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:514–21.

Fritsché R, Pahud JJ, Pecquet S, Pfeifer A. Induction of systemic immunologic tolerance to β-lactoglobulin by oral administration of a whey protein hydrolysate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:266–73.

Billeaud C, Guillet J, Sandler B. Gastric emptying in infants with or without gastro-oesophageal reflux according to the type of milk. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990.

Halken S, Hansen KS, Jacobsen HP, Estmann A, Christensen AEF, Hansen LG, et al. Comparison of a partially hydrolyzed infant formula with two extensively hydrolyzed for allergy prevention: a prospective, randomized study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2000;11:149–61.

Osborn DA, Sinn JKH, Jones LJ. Infant formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018.

Dupont C. Cow’s milk allergy: protein hydrolysates or amino acid formula? AAPS Adv Pharm Sci Ser. 2014;12:359–71.

Allen KJ, Davidson GP, Day AS, Hill DJ, Kemp AS, Peake JE, et al. Management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants and young children: an expert panel perspective. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45:481–6.

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Shannon FT. Early solid feeding and recurrent childhood eczema: a 10-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1990;86:541–6.

Morgan J, Williams P, Norris F, Williams CM, Larkin M, Hampton S. Eczema and early solid feeding in preterm infants. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:309–14.

Snijders BEP, Thijs C, Van Ree R, Van Den Brandt PA. Age at first introduction of cow milk products and other food products in relation to infant atopic manifestations in the first 2 years of life: The KOALA birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e115-122.

Wopereis H, Sim K, Shaw A, Warner JO, Knol J, Kroll JS. Intestinal microbiota in infants at high risk for allergy: effects of prebiotics and role in eczema development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:1334-1342.e5.

Wopereis H, Oozeer R, Knipping K, Belzer C, Knol J. The first thousand days—intestinal microbiology of early life: establishing a symbiosis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:428–38.

Bindels LB, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Walter J. Opinion: towards a more comprehensive concept for prebiotics. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12:303–10.

Moro G, Arslanoglu S, Stahl B, Jelinek J, Wahn U, Boehm G. A mixture of prebiotic oligosaccharides reduces the incidence of atopic dermatitis during the first six months of age. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:814–9.

Cuello-Garcia CA, Fiocchi A, Pawankar R, Yepes-Nuñez JJ, Morgano GP, Zhang Y, et al. World Allergy Organization-McMaster University guidelines for allergic disease prevention (GLAD-P): prebiotics. World Allergy Organ J. 2016;9:10.

Muraro A, Werfel T, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Roberts G, Beyer K, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;69:1008–25.

De Greef E, Hauser B, Devreker T, Veereman-Wauters G, Vandenplas Y. Diagnosis and management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants. World J Pediatr. 2012;8:19–24.

Hill DJ, Hosking CS, Heine RG. Clinical spectrum of food allergy in children in Australia and South-East Asia: Identification and targets for treatment. Ann Med. 1999;272–81.

Restani P, Gaiaschi A, Plebani A, Beretta B, Velonà T, Cavagni G, et al. Evaluation of the presence of bovine proteins in human milk as a possible cause of allergic symptoms in breast-fed children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2000;84:353–60.

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: a review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141:41–58.

Høst A, Koletzko B, Dreborg S, Muraro A, Wahn U, Aggett P, et al. Dietary products used in infants for treatment and prevention of food allergy. Joint statement of the European Society for Paediatric Allergology and Clinical Immunology (ESPACI) Committee on hypoallergenic formulas and the European Society for Paediatric. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:80–4.

Hill DJ, Murch SH, Rafferty K, Wallis P, Green CJ. The efficacy of amino acid-based formulas in relieving the symptoms of cow’s milk allergy: a systematic review. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:808–22.

Vanderhoof J, Moore N, De Boissieu D. Evaluation of an amino acid-based formula in infants not responding to extensively hydrolyzed protein formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;63:531–3.

Łoś-Rycharska E, Kieraszewicz Z, Czerwionka-Szaflarska M. Medium chain triglycerides (MCT) formulas in paediatric and allergological practice. Prz Gastroenterol. 2016;4:226–31.

Bhatia J, Greer F. Use of soy protein-based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1062–8.

Katz Y, Gutierrez-Castrellon P, González MG, Rivas R, Lee BW, Alarcon P. A comprehensive review of sensitization and allergy to soy-based products. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2014;46:272–81.

Matthai J, Sathiasekharan M, Poddar U, Sibal A, Srivastava A, Waikar Y, et al. Guidelines on Diagnosis and Management of Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy , Gautam Ray, S Geetha and SK Yachha for the Indian Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; Pediatric Gastroenterology Chapter of Indian Academy of Pediat. Indian Pediatr. 2020.

Vandenplas Y, Castrellon PG, Rivas R, Gutiérrez CJ, Garcia LD, Jimenez JE, et al. Safety of soya-based infant formulas in children. Br J Nutr. 2014;111:1340–60.

Testa I, Salvatori C, Di Cara G, Latini A, Frati F, Troiani S, et al. Soy-based infant formula: are phyto-oestrogens still in doubt? Front Nutr. 2018;5:110.

Pedrosa Delgado M, Pascual CY, Larco JI, Martín EM. Palatability of hydrolysates and other substitution formulas for cow’s milk-allergic children: a comparative study of taste, smell, and texture evaluated by healthy volunteers. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2006;16:351–6.

D’Auria E, Sala M, Lodi F, Radaelli G, Riva E, Giovannini M. Nutritional value of a rice-hydrolysate formula in infants with cow’s milk protein allergy: a randomized pilot study. J Int Med Res. 2003;31:215–22.

Vandenplas Y, De Greef E, Hauser B. Safety and tolerance of a new extensively hydrolyzed rice protein-based formula in the management of infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173:1209–16.

Lai PY, Cottingham KL, Steinmaus C, Karagas MR, Miller MD. Arsenic and rice: translating research to address health care providers’ needs. J Pediatr. 2015;167:797–803.

Payot F, Lachaux A, Lalanne F, Kalach N. Randomized trial of a yogurt-type amino acid-based formula in infants and children with severe cow’s milk allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66:135–40.

Candy DCA, Van Ampting MTJ, Oude Nijhuis MM, Wopereis H, Butt AM, Peroni DG, et al. A synbiotic-containing amino-acid-based formula improves gut microbiota in non-IgE-mediated allergic infants. Pediatr Res. 2018;83:677–86.

Berni Canani R, Nocerino R, Terrin G, Frediani T, Lucarelli S, Cosenza L, et al. Formula selection for management of children with cow’s milk allergy influences the rate of acquisition of tolerance: a prospective multicenter study. J Pediatr. 2013;163:771–7.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2:i-iv, 1-88.

Vogel C, Zwolinsky S, Griffiths C, Hobbs M, Henderson E, Wilkins E. A Delphi study to build consensus on the definition and use of big data in obesity research. Int J Obes. 2019;43:2573–86.

Acknowledgements

Medical writing support in the development of this manuscript was provided by Dr. Ahmed Elgebaly of Clinart MENA and funded by Nutricia Middle East.

Funding

The consensus recommendations and algorithms presented in this manuscript were discussed and formulated through a two-stage Delphi consensus, involving virtual advisory board meeting on the 30th of October 2020. The meeting was facilitated by the Nutricia Middle East. Medical writing support in the development of this manuscript was provided by Dr. Ahmed Elgebaly of Clinart MENA and funded by Nutricia Middle East.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAEl-H, MHFEl-S, and SAl-H contributed to the conceptualization, data curation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. MAEl-H and MHFEl-S contributed equally to this work. All other authors contributed to the methodology, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors confirm their final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Mostafa El-Hodhod has received honoraria for delivering scientific talks sponsored by Nutricia, Nestle, and Danone. All other authors report no financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Hodhod, M.A., El-Shabrawi, M.H.F., AlBadi, A. et al. Consensus statement on the epidemiology, diagnosis, prevention, and management of cow's milk protein allergy in the Middle East: a modified Delphi-based study. World J Pediatr 17, 576–589 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-021-00476-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-021-00476-3