Abstract

Objectives

We sought to investigate angiographic indications for the use of the STENTYS technique and evaluated the long-term safety and clinical efficacy of the stent.

Background

Coronary lesions involving complex anatomy, including aneurysmatic, ectatic, or tapered vessel segments often carry a substantial risk of stent malapposition. The self-apposing stent technique may reduce the risk of stent malapposition and therefore improve clinical outcomes.

Methods

A total of 120 consecutive patients treated with the STENTYS stent were included (drug-eluting stent (DES) n = 101, bare-metal stent (BMS) n = 19). All lesions were scored for angiographic indications for the STENTYS stent, including aneurysms, ectasias, tapering, absolute diameters, bifurcation lesions, and saphenous vein grafts. Off-line quantitative coronary angiography analyses were performed pre-procedure and post-procedure. Five years follow-up was obtained including cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI), target vessel revascularisation, stent thrombosis, and the composite endpoint target vessel failure (cardiac death, TV-MI and target vessel revascularisation).

Results

Angiographic indications for STENTYS use were aneurysm (30%), ectasia (19%), tapering (27%), bifurcation lesions (8%), and saphenous vein graft lesions (16%) and absolute diameters (22%). Mean maximal diameter was 4.51 ± 0.99 mm. At 5‑year follow-up target vessel failure rates were 24.1% in the total cohort (DES 22.8% vs. BMS 33%, p = 0.26). Definite stent thrombosis rate was 3.8% at 5‑year follow-up in this cohort with complex and high-risk lesions (DES 4.5% vs. BMS 0%, p = 0.39).

Conclusions

Angiographic indications for the use of the self-apposing stent were complex lesions with atypical coronary anatomy. Our data showed reasonable stent thrombosis rates at 5‑year follow-up, considering the high-risk lesion characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

What’s new

-

This is the first registry reporting on the indications that made interventionalists opt for the use of the STENTYS self-apposing technique in daily clinical practise with a 5-year clinical follow-up.

-

This single-centre registry showed that operators tend to choose this stent technique in complex lesions, including coronary artery disease with aneurysm (30%), ectasia (19%), tapering (27%), bifurcation lesions (8%), saphenous vein graft lesions (16%) and absolute target vessel diameters (22%).

-

At 5‑year follow-up, overall stent thrombosis rate was 3.8%, which is reasonable considering the complexity of this cohort where proper sizing with tubular balloon-expandable stents could be difficult in vessel segments with varying vessel diameters.

-

The multi-centre enrolling SIZING registry will give us insights into the performance of this device in lesions with vessel diameter variance.

Introduction

Percutaneous coronary intervention of coronary lesions involving complex anatomy such as aneurysm, ectasia or tapering, remains challenging in daily clinical practice. Due to the varying vessel diameters within the target vessel, optimal stent sizing can be difficult. Particularly in these complex lesions, in-stent restenosis and late stent thrombosis remain significant problems, even when we use a contemporary drug-eluting stent (DES) [1]. When a stent/vessel size mismatch occurs, incompletely apposed stent struts could delay tissue coverage, and therefore predispose for the occurrence of stent thrombosis [2, 3]. Proper sizing using balloon-expandable stents in lesions with varying vessel diameters can be more difficult, since balloon-expandable stents are tubular by nature and limited to a maximum expansion diameter [4]. The nitinol self-apposing STENTYS stent (STENTYS SA, Paris, France) can adjust to varying lumen diameters (Fig. 1). This technique might improve clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention of vessels involving varying diameters due to its superior strut apposition [5]. Moreover, large vessel diameters often exceed the expansion capacity of currently available balloon-expandable stents [6]. This stent can expand up to 6.0 mm which results in adequate apposition even in absolute vessel diameters. In the present single-centre study, we aimed to evaluate what the operator indication was for the use of the self-apposing stent in daily clinical practice. We report the angiographic indication for the stent, with angiographic and clinical outcomes up to 5‑year follow-up.

Materials and methods

Study patients and setting

All consecutive patients treated with the STENTYS stent since the introduction of the device in our centre from April 2010 until January 2016 were evaluated for this registry. Patients were excluded if they presented with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or were enrolled in a randomised trial. All other clinical indications for percutaneous coronary intervention were allowed. Percutaneous coronary intervention involving the STENTYS device was in the setting of routine clinical care. The choice for a drug-eluting stent or bare-metal stent (BMS) was at the discretion of the operator. Pre-implantation sizing was done by visual estimation. All patients provided written informed consent for this registry. All patients were pre-loaded with aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, if not already on chronic therapy. Patients received 5,000 IU of unfractionated heparin at the start of the procedure. The use of peri-procedural glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitors was left at the discretion of the operator.

Study device

The STENTYS stent is a new generation self-expanding device, made of a nitinol platform, a biocompatible nickel and titanium alloy. The stent is 6 French-compatible and is delivered using a rapid-exchange delivery system over a conventional 0.014″ guidewire. It is available in 3 lengths (17 mm, 22 mm and 27 mm), and in three diameter sizes: small (2.5–3.0 mm), medium (3.0–3.5 mm), and large (3.5–4.5 mm). The strut thickness is 102 microns (small size) or 133 microns (medium and large sizes). The large STENTYS can expand over 6.0 mm suitable for absolute vessel diameters of >4.5 mm. The stent is available as bare-metal stent and drug-eluting stent (paclitaxel or sirolimus). Since apposition is possible in large and variable vessel diameters of, for example, proximal and distal main branches, the stent can be used safely and effectively in bifurcation lesions [7,8,9] and in saphenous vein grafts [10]. Moreover, the nitinol platform can enlarge further after implantation. Therefore, the STENTYS device is extensively evaluated in patients with acute myocardial infarction in the APPOSITION trials [5, 11,12,13], which revealed lower rates of strut mal-apposition as compared with balloon-expandable stents and favourable clinical results. During the present study, the novel balloon-based delivery system Xposition was not yet available for commercial use.

Angiographic data acquisition and definitions

An experienced interventional cardiologist (KTK) retrospectively reviewed the procedural report and procedural angiograms of all lesions treated with STENTYS to obtain lesion characteristics and to access the angiographic indication for this device if it was not stated in the report. The following angiographic indications were specified; aneurysm; ectasias; tapering; absolute reference vessel diameter 4.0–5.0 mm, bifurcation lesions and lesions located in saphenous vein grafts. Aneurysm was defined as localised or segmental dilatation which exceeds the diameter of normal adjacent segments by 1.5 times [14]. Ectasia was defined as irregular diffuse dilatation (>1.5 times the normal diameter) that involves more than one third of the length of the coronary artery [15, 16]. Tapering was defined as a significant diameter change of ≥1 mm from the proximal to the distal vessel segment. Offline quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) analyses were performed using dedicated software (QAngioXA version 7.3; Medis, Leiden, the Netherlands). Standardised QCA methodology was used including a bifurcation algorithm for bifurcation lesions. Pre- and post-procedural reference vessel diameter, minimal luminal diameter and percentage diameter stenosis (%DS) were obtained. Pre-implantation D‑max is obtained to assess maximal luminal diameters at baseline. Acute gain was defined as the difference between pre-procedural and post-procedural minimal luminal diameter. Longitudinal geographic mismatch on QCA was defined as the entire length of the lesion (as defined by QCA) not completely covered by the stent. Angiographic success was defined as final residual stenosis of less than 20% by offline QCA and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 3 flow on the final angiogram without geographic mismatch.

Follow-up and outcomes

Patients were contacted individually to obtain follow-up data. Hospital records and coronary angiograms were reviewed to complete information. Reported clinical outcomes included cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction (TV-MI), non-TV-MI, clinically indicated target lesion revascularisation, target vessel revascularisation (TVR), non-TVR, and definite/probable stent thrombosis according to the Academic Research Consortium definitions [17]. Target vessel failure was defined as the composite of cardiac death, TV-MI or TVR. Procedural success was defined as angiographic success without in-hospital target vessel failure.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, categorical variables as frequencies. We performed comparisons of variables using the two-sided Student-t test, chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Event rates were assessed by Kaplan-Meier estimates and compared with the log-rank test. Follow-up was censored at 5 years or at the last known date of follow-up, whichever came first. We used the SPSS software package (version 24, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline patient characteristics and procedural characteristics

Between April 2010 and January 2016, 120 patients were included in our registry including 19 STENTYS bare-metal stents, and 101 STENTYS drug-eluting stents. We report the outcome separately. Baseline clinical characteristics are summarised in Table 1 of the online supplementary material. Mean age was 65 ± 12 years in the group with a drug-eluting stents vs. 67 ± 13 in the group with a bare-metal stent. In the group with a drug-eluting stent, 46% of patients had stable angina, 16% unstable angina and 39% non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). In the group with a bare-metal stent, 53% of patients had stable angina, 26% unstable angina and 21% NSTEMI.

Lesion and procedural characteristics are shown in Table 2 of the online supplementary material. A total of 124 lesions were treated (study lesions). Of this total, 104 lesions were treated with the STENTYS drug-eluting stent and 20 with the STENTYS bare-metal stent. D‑max was 4.51 ± 0.99 mm in the group with a drug-eluting stent and 4.63 ± 1.05 mm in the group with a bare-metal stent (p = 0.64). A considerable number of patients had a pre-implantation D‑max of ≥4.0 to ≤5.0 mm (38% vs. 37% respectively, p = 0.95). In both groups, there was even a pre-implantation D‑max of ≥5.0 mm in approximately one third of cases (28% vs. 37% respectively, p = 0.42). Geographic mismatch occurred in 2% in the group with a drug-eluting stent vs. 5% in the group with a bare-metal stent (p = 0.46). Angiographic success was 69% in the group with a drug-eluting stent vs. 68% in the group with a bare-metal stent (p = 0.94), similar to the procedural success due to no in-hospital target vessel failure.

Angiographic indications and results

Angiographic indications for operators to choose the STENTYS stent, were aneurysm (30%), ectasia (19%), tapering (27%), bifurcation lesions (8%), saphenous vein graft lesions (16%) and absolute target vessel diameters (22%) (Tab. 1). More than 1 angiographic indication could apply, for example, tapering and absolute target vessel diameter (Fig. 2). QCA results are summarised in Tab. 2. Reference vessel diameter, %DS and the minimal luminal diameter of all angiographic indications are shown separately illustrating the angiographic differences between the groups. In tapering, the reference vessel diameter of the proximal edge is remarkably larger than the reference vessel diameter in the distal edge of the treated segment. Angiographic outcomes for the bifurcation lesions are shown in Table 3 of the online supplementary material.

Examples of STENTYS cases. Pre-procedural and post-procedural coronary angiograms of 4 cases from our cohort including a pre-procedural angiogram of an aneurysmatic vessel, e result after STENTYS placement, b pre-procedural angiogram of an ectatic vessel, f result after STENTYS placement, c pre-procedural angiogram of saphenous vein graft lesion, g result after STENTYS placement, d pre-procedural angiogram of a tapered left main lesion, (H) result after STENTYS placement

Clinical outcomes

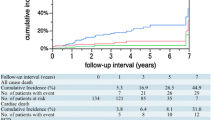

Clinical follow-up was obtained for all patients with a median follow-up of 51 months (IQR 42–60). One patient was lost to follow-up due to emigration to Suriname 2 years after baseline percutaneous coronary intervention and is censored from the date of emigration. Target vessel failure was observed in 25 patients (24.1%), 19 (22.8%) in the group with a drug-eluting stent vs. 6 (33%) in the group with a bare-metal stent (Tab. 3). Landmark analysis at 2‑year up to 5‑year follow-up revealed an incremental target vessel failure rate of 13.3% in the group with a drug-eluting stent and 15.2% in the group with a bare-metal stent (p = 0.73) (Fig. 3). In the total cohort, definite stent thrombosis occurred in 4 cases (3.8%). Stent thrombosis characteristics are shown in Table 4 of the online supplementary material. Individual clinical endpoints are shown in Tab. 3 and Fig. 4. Clinical outcomes per angiographic indication are shown in Table 5 of the online supplementary material. Comparison between the bare-metal stent group and the drug-eluting stent group should be interpreted with caution due to the non-randomised design and the small sample size.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularisation, and probable and definite stent thrombosis. a Cumulative event rate of individual endpoint cardiac death by Kaplan-Meier estimates. b Cumulative event rate of the individual endpoint target vessel myocardial infarction by Kaplan-Meier estimates. c Cumulative event rate of the individual endpoint target lesion revascularisation by Kaplan-Meier estimates. d Cumulative event rate of the individual endpoint probable and definite stent thrombosis by Kaplan Meier estimates

Discussion

This study evaluates the angiographic indications for the use of the STENTYS device according to experienced interventionalists with the report of 5‑year clinical outcome in a subgroup of complex patients. Indications for STENTYS use was coronary aneurysm, ectasia, tapering, absolute vessel diameters, bifurcation lesions and lesions located in saphenous vein grafts. Our QCA data demonstrates that this device is effective in large variable reference vessel diameters in a cohort with high-risk complex coronary anatomy.

Clinical experience with the STENTYS stent

Several theoretic advantages of the nitinol self-apposing platform were previously evaluated in selected cohorts. Naber et al. observed a definite stent thrombosis rate of 1% at 6‑month and 0% at 12-month follow-up in bifurcation lesions [7]. A large STEMI registry with STENTYS bare-metal stent and paclitaxel-eluting stent (PES) revealed definite stent thrombosis rates of 3.3% at 2‑year follow-up [13]. Less data is available for the stent performance in all-comer populations. An evaluation of a small real-world cohort reveals that interventionalists chose the STENTYS device in a comparable selection of angiographic situations, including bifurcation lesions, acute coronary syndrome and ectatic coronaries, with a stent thrombosis rate of 2.5% at 21 ± 13 months [18]. Another real-world single-centre experience with both STENTYS bare-metal stent and paclitaxel-eluting stent from Italy reported a stent thrombosis rate of 1.8% at 23.6 ± 12.6 months [19]. A larger multicentre cohort reported stent thrombosis rates of 2.6% at 2.5 years in all-comer patients, based on usage of STENTYS bare-metal stent, paclitaxel-eluting stent and sirolimus-eluting stent [20]. In the present study, we observed a geographic mismatch in 2% in the group with a drug-eluting stent and 5% in the group with a bare-metal stent (p = 0.46), and overall stent thrombosis rate of 3.8% at 5‑year follow-up. Considering the complexity of our cohort including both STENTYS bare-metal stent and paclitaxel-eluting stent, these indicators for device performance are acceptable. The low angiographic success rates of 69% in the group with a drug-eluting stent and 68% in the group with a bare-metal stent is partly explained by the fact the we incorporated a geographic mismatch and measured the residual stenosis on off-line QCA. These success rates should be interpreted with caution since QCA analyses might overestimate residual stenosis in aneurysmatic and ectatic lesions.

Comparison with contemporary balloon expandable stents

It is well-known that complex target lesion anatomy is associated with an increased risk of adverse outcome [21, 22]. Using the SYNTAX score, an angiographic scoring system quantifying the complexity of coronary artery disease, it is possible to identify high-risk patients based on angiographic characteristics [23, 24]. Unprotected left main, multi-vessel disease, longer lesions, bifurcation or trifurcation lesions and large thrombus load are incorporated and considered more complex. A recent pooled analysis evaluating new-generation balloon-expandable drug-eluting stents, including stents eluting everolimus and zotarolimus, and biodegradable polymer stents eluting biolimus and sirolimus, demonstrated a definite stent thrombosis rate of 1.0% at 2‑year follow-up in patients with a higher coronary complexity (SYNTAX score > 11) [25]. The RESOLUTE all-comers trial comparing the Resolute zotarolimus-eluting stent with the Xience V everolimus-eluting stent revealed definite stent thrombosis rates of 1.2% vs. 0.4% (p = 0.14) respectively in a pre-specified subgroup of complex patients at 1‑year follow-up [26]. The same trial reported definite stent thrombosis rates of 1.6% vs. 0.8% (p = 0.08) respectively at 5‑year follow-up in an all-comers population [27]. Our observations of much higher stent thrombosis rates could partially be explained by the atypical complexities including aneurysms, ectasia and large tapering. Moreover, the patients were treated with the STENTYS bare-metal stent or paclitaxel-eluting stent delivered with the conventional delivery system. The Xposition delivery system with the sirolimus-eluting STENTYS device, where precise stent delivery is made possible by a delivery balloon which is retracted after stent delivery, might improve clinical outcome in complex coronary anatomy [28].

Study limitations

This study is limited by its observational design. It is a small, single-centre cohort study of complex lesions. A matched control group with such atypical anatomical high-risk lesions treated with balloon-expandable stents was not available. The STENTYS use, including the choice for STENTYS drug-eluting stent or bare-metal stent was at the discretion of the operator. The angiograms were reviewed by a single expert only. No routine angiographic follow-up was performed in these patients. Finally, clinical outcomes were not adjudicated by an independent clinical endpoint committee.

Conclusion

This single-centre registry showed that operators tend to choose this stent technique in complex lesions. Considering the high-risk lesion characteristics, stent thrombosis rates are reasonable at 5‑year follow-up. The STENTYS platform seems safe and effective in patients with an atypical anatomy. The enrolling SIZING registry will give us insights into the performance of this device in lesions with vessel diameter variance [29].

References

Cook S, Eshtehardi P, Kalesan B, et al. Impact of incomplete stent apposition on long-term clinical outcome after drug-eluting stent implantation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1334–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehr484.

Gutierrez-Chico JL, Regar E, Nuesch E, et al. Delayed coverage in malapposed and side-branch struts with respect to well-apposed struts in drug-eluting stents: in vivo assessment with optical coherence tomography. Circulation. 2011;124:612–23. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014514.

Cook S, Ladich E, Nakazawa G, et al. Correlation of intravascular ultrasound findings with histopathological analysis of thrombus aspirates in patients with very late drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Circulation. 2009;120:391–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.854398.

Foin N, Alegria E, Sen S, et al. Importance of knowing stent design threshold diameters and post-dilatation capacities to optimise stent selection and prevent stent overexpansion/incomplete apposition during PCI. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:755–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.09.170.

van Geuns RJ, Tamburino C, Fajadet J, et al. Self-expanding versus balloon-expandable stents in acute myocardial infarction: results from the APPOSITION II study: self-expanding stents in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1209–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2012.08.016.

Foin N, Sen S, Allegria E, et al. Maximal expansion capacity with current DES platforms: a critical factor for stent selection in the treatment of left main bifurcations? EuroIntervention. 2013;8:1315–25. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV8I11A200.

Naber CK, Pyxaras SA, Nef H, et al. Final results of a self-apposing paclitaxel-eluting stent fOr the PErcutaNeous treatment of de novo lesions in native bifurcated coronary arteries study. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:356–8. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJY15M06_02.

Verheye S, Grube E, Ramcharitar S, et al. First-in-man (FIM) study of the Stentys bifurcation stent – 30 days results. EuroIntervention. 2009;4:566–71.

Verheye S, Ramcharitar S, Grube E, et al. Six-month clinical and angiographic results of the STENTYS(R) self-apposing stent in bifurcation lesions. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:580–7. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV7I5A94.

IJsselmuiden AJJ, Simsek C, van Driel AG, et al. Comparison between the STENTYS self-apposing bare metal and paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents for the treatment of saphenous vein grafts (ADEPT trial). Neth Heart J. 2018;26:94–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-017-1066-0.

van Geuns RJ, Yetgin T, La Manna A, et al. STENTYS Self-Apposing sirolimus-eluting stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the randomised APPOSITION IV trial. EuroIntervention. 2016;11(11):e1267–e74. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV11I11A248.

Grundeken MJ, Lu H, Vos N, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction caused by bifurcation culprit lesions treated with the Stentys self-apposing coronary Stent: results from the APPOSITION III study. J Invasive Cardiol. 2017;29:253–8.

Lu H, Grundeken MJ, Vos NS, et al. Clinical outcomes with the STENTYS self-apposing coronary stent in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: two-year insights from the APPOSITION III (A Post-Market registry to assess the STENTYS self-exPanding COronary Stent In AcuTe MyocardIal InfarctiON) registry. EuroIntervention. 2017;13(5):e572–e7. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-16-00676.

Syed M, Lesch M. Coronary artery aneurysm: a review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1997;40:77–84.

Manginas A, Cokkinos DV. Coronary artery ectasias: imaging, functional assessment and clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1026–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi725.

Yavuz S, Eris C, Surer S, et al. eComment. Coronary artery dilatation: ectasia or aneurysm. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2013;17:636–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivt335.

Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.685313.

Pastormerlo LE, Ciardetti M, Coceani M, et al. Self-expanding stent for complex percutaneous coronary interventions: A real life experience. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17:186–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carrev.2016.02.005.

Silenzi S, Grossi P, Mariani L, et al. A real world single centre experience using the STENTYS self-expanding coronary stent. Int J Cardiol. 2016;209:57–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.02.010.

Gaede L, Liebetrau C, Dorr O, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after implantation of the self-expandable STENTYS stent in a large, multicenter cohort. Coron Artery Dis. 2017;28:588–96. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000533.

Genereux P, Redfors B, Witzenbichler B, et al. Angiographic predictors of 2‑year stent thrombosis in patients receiving drug-eluting stents: Insights from the ADAPT-DES study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;89:26–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.26409.

Yeh RW, Kereiakes DJ, Steg PG, et al. Lesion complexity and outcomes of extended dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2213–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.09.011.

Wykrzykowska JJ, Garg S, Girasis C, et al. Value of the SYNTAX score for risk assessment in the all-comers population of the randomized multicenter LEADERS (Limus Eluted from A Durable versus ERodable Stent coating) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:272–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.044.

Sianos G, Morel MA, Kappetein AP, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2005;1:219–27.

Piccolo R, Pilgrim T, Heg D, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of new-generation versus early-generation drug-eluting stents according to complexity of coronary artery disease: a patient-level pooled analysis of 6,081 patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1657–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2015.08.013.

Stefanini GG, Serruys PW, Silber S, et al. The impact of patient and lesion complexity on clinical and angiographic outcomes after revascularization with zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents: a substudy of the RESOLUTE All Comers Trial (a randomized comparison of a zotarolimus-eluting stent with an everolimus-eluting stent for percutaneous coronary intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2221–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.036.

Iqbal J, Serruys PW, Silber S, et al. Comparison of zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting coronary stents: final 5‑year report of the RESOLUTE all-comers trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(6):e2230. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.002230.

Lu H, IJsselmuiden AJ, Grundeken MJ, et al. First-in-man evaluation of the novel balloon delivery system STENTYS Xposition S for the self-apposing coronary artery stent: impact on longitudinal geographic miss during stenting. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:1341–5. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJY15M05_07.

Den Heijer P, Simsek C, Weevers A, et al. Worldwide everyday practice registry assessing the Xposition S Self-Apposing stent in challenging lesions with vessel diameter variance (SIZING registry). Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics; Denver. 2017.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

H. Lu, R.J. Bekker, M.J. Grundeken, P. Woudstra, J.J. Wykrzykowska, J.G.P. Tijssen, R.J. de Winter and K.T. Koch declare that they have no competing interests.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

12471_2018_1111_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Fig. 1 IVUS post-stenting showing apposition of the STENTYS stent in a tapered left main coronary artery. The proximal section of the stent, which was located in the left main coronary artery, has a larger diameter (4.4 mm) and tapers to the distal section of the stent, located in the left ascending descending coronary artery, with a diameter of 2.6 mm (right panel), with good overall stent apposition in both vessel segments

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics

Table 2. Lesion and procedural characteristics

Table 3. Quantitative coronary angiography results (QCA) Bifurcation table

Table 4. Characteristics of patients with stent thrombosis

Table 5. Clinical outcomes by angiographic indication

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, H., Bekker, R.J., Grundeken, M.J. et al. Five-year clinical follow-up of the STENTYS self-apposing stent in complex coronary anatomy: a single-centre experience with report of specific angiographic indications. Neth Heart J 26, 263–271 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-018-1111-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12471-018-1111-7