Abstract

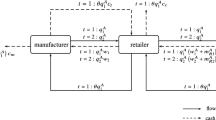

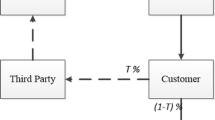

A closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) is the process of restoring the used product to useful life. The quantity of returned products has environmental and economic impacts on the CLSC. But, for the implementation of CLSC, one of the major barriers is the uncertain quantity of returned products. Therefore, we examine a two-period CLSC model with a dual collection channel under uncertainty in return quantity. In the model, a third party and a manufacturer compete to collect used products based on the acquisition prices offered to consumers in the second period. During the first period, the manufacturer relies solely on raw materials to produce a new product. In the second period, the manufacturer produces an improved product using both raw materials and used products. Because an improved new version of the product is now available, some consumers decide to return their first-period purchases for the improved product. The problem is formulated as a two-period newsvendor model and solved using the backward induction approach. It is shown that the acquisition price and transfer price offered by the manufacturer increase the quantity of the returned product. The acquisition price offered by the third party first increases and then decreases if the competition between the collectors is low, but the acquisition price increases when the competition is high.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Agrawal VV, Ferguson M, Toktay LB, Thomas VM (2012) Is leasing greener than selling? Manage Sci 58(3):523–533

Aras N, Boyaci T, Verter V (2004) The effect of categorizing returned products in remanufacturing. IIE Trans 36(4):319–331

Atasu A, Souza GC (2013) How does product recovery affect quality choice? Prod Oper Manag 22(4):991–1010

Bakal IS, Akcali E (2006) Effects of random yield in remanufacturing with price-sensitive supply and demand. Prod Oper Manag 15(3):407–420

Cao K, He P, Liu Z (2020) Production and pricing decisions in a dual-channel supply chain under remanufacturing subsidy policy and carbon tax policy. J Oper Res Soc 71(8):1199–1215

Cetin CB, Zaccour G (2023) Remanufacturing with innovative features: a strategic analysis. Eur J Oper Res 310(2):655–669

Chen JM, Chi CY (2019) Reverse channel choice in a closed-loop supply chain with new and differentiated remanufactured goods. J Ind Prod Eng 36(2):81–96

Chen X, Li K, Wang F, Li X (2020) Optimal production, pricing and government subsidy policies for a closed loop supply chain with uncertain returns. J Ind Manag Optim 16(3):1389

Ciftci K, Tanai Y, Wilson GR (2023) An optimal pricing and quality assessment model for consumer returns in a multi-period closed-loop supply chain. Int J Oper Res 47(3):273–296

Das K, Chowdhury AH (2012) Designing a reverse logistics network for optimal collection, recovery and quality-based product-mix planning. Int J Prod Econ 135(1):209–221

De Giovanni P, Zaccour G (2019) Optimal quality improvements and pricing strategies with active and passive product returns. Omega 88:248–262

Debo LG, Toktay LB, Van Wassenhove LN (2005) Market segmentation and product technology selection for remanufacturable products. Manage Sci 51(8):1193–1205

Dobos I, Richter K (2006) A production/recycling model with quality consideration. Int J Prod Econ 104(2):571–579

Dong J, Sun S, Gao G, Yang R (2021) Pricing and strategy selection in a closed-loop supply chain under demand and return rate uncertainty. 4OR 19(4):501–530

Dou G, Cao K (2020) A joint analysis of environmental and economic performances of closed-loop supply chains under carbon tax regulation. Comput Ind Eng 146:106624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2020.106624

El Saadany AM, Jaber MY (2010) A production/remanufacturing inventory model with price and quality dependent return rate. Comput Ind Eng 58(3):352–362

Ferguson M, Guide VD Jr, Koca E, Souza GC (2009) The value of quality grading in remanufacturing. Prod Oper Manag 18(3):300–314

Ferrer G, Swaminathan JM (2006) Managing new and remanufactured products. Manage Sci 52(1):15–26

Fleischmann M, Kuik R (2003) On optimal inventory control with independent stochastic item returns. Eur J Oper Res 151(1):25–37

Fleischmann M, Bloemhof-Ruwaard JM, Dekker R, Van der Laan E, Van Nunen JA, Van Wassenhove LN (1997) Quantitative models for reverse logistics: a review. Eur J Oper Res 103(1):1–17

Galbreth MR, Boyacı T, Verter V (2013) Product reuse in innovative industries. Prod Oper Manag 22(4):1011–1033

Gan SS, Pujawan IN, Widodo B (2018) Pricing decisions for short life-cycle product in a closed-loop supply chain with random yield and random demands. Oper Res Perspect 5:174–190

Gaula AK, Jha JK (2023) Pricing and quality improvement strategies in a closed-loop supply chain with dual collection channel. Int J Syst Sci: Oper Logist 10(1):2244416

Giri BC, Masanta M (2022) A closed-loop supply chain model with uncertain return and learning-forgetting effect in production under consignment stock policy. Oper Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-020-00571-9

Giri BC, Sharma S (2016) Optimal production policy for a closed-loop hybrid system with uncertain demand and return under supply disruption. J Clean Prod 112:2015–2028

Gong X, Zhou SX (2013) Optimal production planning with emissions trading. Oper Res 61(4):908–924

Gu Q, Tagaras G (2014) Optimal collection and remanufacturing decisions in reverse supply chains with collector’s imperfect sorting. Int J Prod Res 52(17):5155–5170

He Y (2015) Acquisition pricing and remanufacturing decisions in a closed-loop supply chain. Int J Prod Econ 163:48–60

He P, Dou G, Zhang W (2017) Optimal production planning and cap setting under cap-and-trade regulation. J Oper Res Soc 68:1094–1105

He P, He Y, Xu H (2019) Channel structure and pricing in a dual-channel closed-loop supply chain with government subsidy. Int J Prod Econ 213:108–123

Hosseini-Motlagh SM, Nematollahi M, Ebrahimi S (2022) Tri-party reverse supply chain coordination with competitive product acquisition process. J Oper Res Soc 73(2):382–393

Hosseini-Motlagh SM, Johari M, Nematollahi M, Pazari P (2023) Reverse supply chain management with dual channel and collection disruptions: supply chain coordination and game theory approaches. Ann Oper Res 324(1–2):215–248

Inderfurth K (2004) Optimal policies in hybrid manufacturing/remanufacturing systems with product substitution. Int J Prod Econ 90(3):325–343

Inderfurth K (2005) Impact of uncertainties on recovery behavior in a remanufacturing environment: a numerical analysis. Int J Phys Distrib Logist Manag 35:318–336

Jena SK, Sarmah SP (2014a) Optimal acquisition price management in a remanufacturing system. Int J Sustain Eng 7(2):154–170

Jena SK, Sarmah SP (2014b) Price competition and co-operation in a duopoly closed-loop supply chain. Int J Prod Econ 156:346–360

Ketzenberg M (2009) The value of information in a capacitated closed loop supply chain. Eur J Oper Res 198(2):491–503

Ketzenberg ME, Van Der Laan E, Teunter RH (2006) Value of information in closed loop supply chains. Prod Oper Manag 15(3):393–406

Keyvanshokooh E, Ryan SM, Kabir E (2016) Hybrid robust and stochastic optimization for closed-loop supply chain network design using accelerated benders decomposition. Eur J Oper Res 249(1):76–92

Krikke H, Blanc IL, van de Velde S (2004) Product modularity and the design of closed-loop supply chains. Calif Manage Rev 46(2):23–39

Lee DH, Dong M (2009) Dynamic network design for reverse logistics operations under uncertainty. Transp Res Part e: Logist Transp Rev 45(1):61–71

Levi MD, Nault BR (2004) Converting technology to mitigate environmental damage. Manage Sci 50(8):1015–1030

Li X, Li Y, Cai X (2015) Remanufacturing and pricing decisions with random yield and random demand. Comput Oper Res 54:195–203

Li G, Reimann M, Zhang W (2018) When remanufacturing meets product quality improvement: the impact of production cost. Eur J Oper Res 271(3):913–925

Li L, Liao H, Zhou J, Wang Y (2022) Sustainability and optimization methods under uncertainties in closed-loop supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 171:108396

Liang Y, Pokharel S, Lim GH (2009) Pricing used products for remanufacturing. Eur J Oper Res 193(2):390–395

Liao H, Zhang Q, Li L (2023) Optimal procurement strategy for multi-echelon remanufacturing systems under quality uncertainty. Transp Res Part e: Logist Transp Rev 170:103023

Liu K, Wang C (2024) Production and recycling of new energy vehicle power batteries under channel encroachment and government subsidy. Environ Dev Sustain 26(1):1313–1339

Liu H, Lei M, Deng H, Leong GK, Huang T (2016) A dual channel, quality-based price competition model for the WEEE recycling market with government subsidy. Omega 59:290–302

Liu L, Pang C, Hong X (2022) Patented product remanufacturing and technology licensing in a closed-loop supply chain. Comput Ind Eng 172:108634

Mawandiya BK, Jha JK, Thakkar JJ (2020) Optimal production-inventory policy for closed-loop supply chain with remanufacturing under random demand and return. Oper Res Int J 20:1623–1664

Mukhopadhyay SK, Ma H (2009) Joint acquisition and production decisions in remanufacturing under quality and demand uncertainty. Int J Prod Econ 120(1):5–17

Nie J, Liu J, Yuan H, Jin M (2021) Economic and environmental impacts of competitive remanufacturing under government financial intervention. Comput Ind Eng 159:107473

Örsdemir A, Kemahlıoğlu-Ziya E, Parlaktürk AK (2014) Competitive quality choice and remanufacturing. Prod Oper Manag 23(1):48–64

Pan W, Huynh CH (2023) Optimal operational strategies for online retailers with demand and return uncertainty. Oper Manag Res 16(2):755–767

Petruzzi NC, Dada M (1999) Pricing and the newsvendor problem: a review with extensions. Oper Res 47(2):183–194

Pishvaee MS, Torabi SA (2010) A possibilistic programming approach for closed-loop supply chain network design under uncertainty. Fuzzy Sets Syst 161(20):2668–2683

Pishvaee MS, Rabbani M, Torabi SA (2011) A robust optimization approach to closed-loop supply chain network design under uncertainty. Appl Math Model 35(2):637–649

Pokharel S, Liang Y (2012) A model to evaluate acquisition price and quantity of used products for remanufacturing. Int J Prod Econ 138(1):170–176

Robotis A, Boyaci T, Verter V (2012) Investing in reusability of products of uncertain remanufacturing cost: the role of inspection capabilities. Int J Prod Econ 140(1):385–395

Salema MIG, Barbosa-Povoa AP, Novais AQ (2007) An optimization model for the design of a capacitated multi-product reverse logistics network with uncertainty. Eur J Oper Res 179(3):1063–1077

Sarada Y, Sangeetha S (2022) Coordinating a reverse supply chain with price and warranty dependent random demand under collection uncertainties. Oper Res Int Journal 22(4):4119–4158

Savaskan RC, Van Wassenhove LN (2006) Reverse channel design: the case of competing retailers. Manage Sci 52(1):1–14

Savaskan RC, Bhattacharya S, Van Wassenhove LN (2004) Closed-loop supply chain models with product remanufacturing. Manage Sci 50(2):239–252

Shi J, Zhang G, Sha J, Amin SH (2010) Coordinating production and recycling decisions with stochastic demand and return. J Syst Sci Syst Eng 19(4):385–407

Shi J, Zhang G, Sha J (2011a) Optimal production and pricing policy for a closed loop system. Resour Conserv Recycl 55(6):639–647

Shi J, Zhang G, Sha J (2011b) Optimal production planning for a multi-product closed loop system with uncertain demand and return. Comput Oper Res 38(3):641–650

Steeneck DW, Sarin SC (2017) Determining end-of-life policy for recoverable products. Int J Prod Res 55(19):5782–5800

Taleizadeh AA, Moshtagh MS, Moon I (2018) Pricing, product quality, and collection optimization in a decentralized closed-loop supply chain with different channel structures: game theoretical approach. J Clean Prod 189:406–431

Taleizadeh AA, Alizadeh-Basban N, Niaki STA (2019) A closed-loop supply chain considering carbon reduction, quality improvement effort, and return policy under two remanufacturing scenarios. J Clean Prod 232:1230–1250

Thomas VM (2011) The environmental potential of reuse: an application to used books. Sustain Sci 6(1):109–116

Van Wassenhove LN, Zikopoulos C (2010) On the effect of quality overestimation in remanufacturing. Int J Prod Res 48(18):5263–5280

Wang X, Han S (2020) Optimal operation and subsidies/penalties strategies of a multi-period hybrid system with uncertain return under cap-and-trade policy. Comput Ind Eng 150:106892

Wang Q, Zhao D, He L (2016) Contracting emission reduction for supply chains considering market low-carbon preference. J Clean Prod 120:72–84

Wang Z, Huo J, Duan Y (2019) Impact of government subsidies on pricing strategies in reverse supply chains of waste electrical and electronic equipment. Waste Manage 95:440–449

Wang Y, Yu Z, Shen L, Dong W (2021) Impacts of altruistic preference and reward-penalty mechanism on decisions of E-commerce closed-loop supply chain. J Clean Prod 315:128132

Wei J, Wang Y, Zhao J, Gonzalez EDS (2019) Analyzing the performance of a two-period remanufacturing supply chain with dual collecting channels. Comput Ind Eng 135:1188–1202

White AL, Stoughton M, Feng L (1999) Servicizing: the quiet transition to extended product responsibility. Tellus Institute, Boston, p 97

Xia X, Lu M, Wang W (2023) Emission reduction and outsourcing remanufacturing: a comparative study under carbon trading. Expert Syst Appl 227:120317

Xiong Y, Li G (2013) The value of dynamic pricing for cores in remanufacturing with backorders. J Oper Res Soc 64(9):1314–1326

Xiong Y, Zhou Y, Li G, Chan HK, Xiong Z (2013) Don’t forget your supplier when remanufacturing. Eur J Oper Res 230(1):15–25

Xiong Y, Zhao P, Xiong Z, Li G (2016) The impact of product upgrading on the decision of entrance to a secondary market. Eur J Oper Res 252(2):443–454

Xu X, Li Y, Cai X (2012) Optimal policies in hybrid manufacturing/remanufacturing systems with random price-sensitive product returns. Int J Prod Res 50(23):6978–6998

Xu J, Chen Y, Bai Q (2016) A two-echelon sustainable supply chain coordination under cap-and-trade regulation. J Clean Prod 135:42–56

Yenipazarli A (2016) Managing new and remanufactured products to mitigate environmental damage under emissions regulation. Eur J Oper Res 249(1):117–130

Yoo SH (2014) Product quality and return policy in a supply chain under risk aversion of a supplier. Int J Prod Econ 154:146–155

Zhang Z, Liu S, Niu B (2020) Coordination mechanism of dual-channel closed-loop supply chains considering product quality and return. J Clean Prod 248:119273

Zhao J, Wei J, Li M (2017) Collecting channel choice and optimal decisions on pricing and collecting in a remanufacturing supply chain. J Clean Prod 167:530–544

Zhou J, Deng Q, Li T (2018) Optimal acquisition and remanufacturing policies considering the effect of quality uncertainty on carbon emissions. J Clean Prod 186:180–190

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Proof of Proposition 1

2.1 The second period

In the second period, the decision is made by the manufacturer first, then by the retailer, and finally by the third party. Based on the former choices made by the manufacturer and retailer, we determine the third party's reaction. After that, given the manufacturer's prior choices, the retailer's optimal reaction is determined. Finally, the manufacturer's second-period response is calculated.

The third party determines the optimal acquisition price \({p}_{t}\) by optimising its expected profit during the second period \(E\left[{\pi }_{t}\left({p}_{t}\right)\right]\) in Eq. (9), the first derivative of \(E\left[{\pi }_{t}\left({p}_{t}\right)\right]\) w.r.t. \({p}_{t}\) is obtained as

Since \(E\left[{\pi }_{t}\left({p}_{t}\right)\right]\) is concave in \({p}_{t}\) for \(\alpha >0\) as

\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{t}\left({p}_{t}\right)\right]}{\partial {p}_{t}^{2}}= -2\alpha <0.\)

Hence, by setting \(\frac{\partial E\left[{\pi }_{t}\left({p}_{t}\right)\right]}{\partial {p}_{t}}=0\), we get

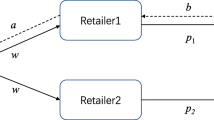

The retailer decides the optimal price \({p}_{2}\) by maximising its expected profit in the second period,

\(E\left[{\pi }_{r,2}\left({p}_{2}\right)\right]=\left({p}_{2}-{w}_{2}\right)\left(a-b{p}_{2}+\upsilon Q\right).\)

The first derivative of \(E\left[{\pi }_{r,2}\left({p}_{2}\right)\right]\) w.r.t. \({p}_{2}\) can be written as

and \(E\left[{\pi }_{r,2}\left({p}_{2}\right)\right]\) is concave in \({p}_{2}\) for \(b>0\) since \(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{r,2}\left({p}_{2}\right)\right]}{\partial {p}_{2}^{2}}=-2b<0.\)

Hence, by setting \(\frac{\partial E\left[{\pi }_{r,2}\left({p}_{2}\right)\right]}{\partial {p}_{2}}=0\), the retailer’s best reaction is obtained as

Finally, the manufacturer maximises its second-period expected profit in Eq. (4), considering the reactions of the third-party collector and retailer to obtain the optimal response. Therefore, using Eq. (4), the partial derivatives of \(E\left[{\pi }_{m,2}\right]\) w.r.t. \({w}_{2}, {p}_{m},{b}_{t},Q\) and \(z\) can be obtained, respectively, as

and

It can be demonstrated that the Hessian matrix provided below is negative definite if \(\delta >\frac{b\left(3\alpha +\beta \right){\gamma }^{2}+\alpha \left(\alpha -\beta \right){\upsilon }^{2}}{4b\alpha \left(\alpha -\beta \right)}\).

By setting the first-order derivatives in Eqs. (25)–(29) to zero and solving them simultaneously to obtain the manufacturer's second-period best reaction, we get

and

The first period

Based on all members' second-period reactions and the manufacturer's first-period decision, we calculate the retailer's best first-period reaction. The retailer sets \({p}_{1}\) to maximise the expected profit. Thus, the total expected profit of the retailer in Eq. (7) is expressed as a function of \({p}_{1}\) and \({w}_{1}\) using Eqs. (22), (24) and (30)–(34), and then differentiating \(E\left[{\pi }_{r}\right]\) w.r.t. \({p}_{1}\), we get

and again differentiating \(E\left[{\pi }_{r}\right]\) w.r.t. \({p}_{1}\), we obtain.

\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{r}\right]}{ \partial {p}_{1}^{2}}=-2b\le 0.\)

By setting \(\frac{\partial E\left[{\pi }_{r}\right]}{ \partial {p}_{1}}\) to zero and solving for \({p}_{1}\), the retailer’s optimal first-period reaction is obtained as

Based on the best first-period response of the retailer, the manufacturer will maximise its total expected profit in Eq. (5) by optimising the wholesale price \({w}_{1}\), which is subjected to a constraint that the return quantity in the second period should not exceed the demand in the first period, i.e.

\(2q+\left(\alpha -\beta \right)\left({p}_{m}+{p}_{t}\right)+2\gamma Q+\epsilon \le a-b{p}_{1}.\)

On substituting the second-period responses of all members from Eqs. (22), (24), (30) to (34) and the retailer's reaction from Eq. (36) into Eq. (5), and applying the KKT conditions, we obtain

and

Again differentiating \(E\left[{\pi }_{m}\left({w}_{1}\right)\right]\) w.r.t. \({w}_{1}\), we get

\(\frac{{\partial }^{2}E\left[{\pi }_{m}\left({w}_{1}\right)\right]}{\partial {w}_{1}^{2}}= -b<0.\)

By solving Eqs. (37) and (38) for \({w}_{1}\), the manufacturer's first-period optimal wholesale price is obtained as

Also, to satisfy the non-negativity requirement of the decision variables, the conditions are obtained as.

\(q\le \left(\alpha -\beta \right)\tau \Delta -{Q}^{*}\gamma\) and \(q\le \frac{\left({\alpha }^{2}-{\beta }^{2}\right)\tau \Delta }{3\alpha -\beta }-{Q}^{*}\gamma\).

Here, both the above conditions will be satisfied if

\(q\le \frac{\left({\alpha }^{2}-{\beta }^{2}\right)\tau \Delta }{3\alpha -\beta }-{Q}^{*}\gamma.\)

Therefore, on substituting the expression of \({Q}^{*}\) from Eq. (14) in the above condition, we get

Hence, in order to obtain a unique optimal solution, \(q\) should satisfy constraint (40) along with constraint (5).

Appendix B

Proof of comparison between single collection channel and dual collection channel

5.1 Proof of Corollary

For the dual collection channel, differentiating Eq. (14) w.r.t. \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(b\) and \(\tau\), we get

and

For the single collection channel with the manufacturer as the collector and the conditions \(\beta =0, {\mu }_{t}=0\), the first hand derivative of Eq. (14) w.r.t. \(\alpha\), \(b\) and \(\tau\), are obtained as

and

For the single collection channel with the third party as the collector and the conditions \(\beta =0, {\mu }_{m}=0\), on differentiating Eq. (14) w.r.t \(\alpha\), \(b\) and \(\tau\), we obtain

and

Proof of Proposition 2

For the comparison between the single collection channel with the third party as the collector and the dual collection channel with no collection competition, we get equivalent return quantity as \({\widehat{q}}_{t}=2q+\alpha {p}_{t}+2\gamma Q+{\epsilon }_{t}\) and \(\beta =0\) in Eqs. (10)–(18) and obtain.

if \(a\ge \frac{3b\alpha \gamma \upsilon {c}_{m}+\left(4b\alpha \delta -9b{\gamma }^{2}-\alpha {\upsilon }^{2}\right){\mu }_{m}-\alpha \left(\left(3q+{\mu }_{t}\right)\left(4b\delta -{\upsilon }^{2}\right)+9b{\gamma }^{2}\tau \Delta \right)}{3\alpha \gamma \upsilon }\), then

and

Based on above results, \(E\left[{\pi }_{t}^{D*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{t}^{S*}\right]\le 0\),\(E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{D*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{S*}\right]\ge 0\) and \(E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{D*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{S*}\right]\ge 0\).

Hence, Proposition 2 is proved.

Proof of Proposition 3

For the comparison between the single collection channel with the manufacturer as the collector and the dual collection channel with no collection competition, we get equivalent return quantity as \({\widehat{q}}_{m}=2q+\alpha {p}_{t}+2\gamma Q+{\epsilon }_{m}\) and \(\beta =0\) in Eqs. (10)–(18) and obtain.

If \(a\ge \frac{\alpha \left(5q+\alpha \tau \Delta \right){\upsilon }^{2}+5b\alpha \gamma \upsilon {c}_{m}+\left(4b\alpha \delta -8b{\gamma }^{2}-\alpha {\upsilon }^{2}\right){\mu }_{t}-4b\alpha \left(5q\delta +\left(3{\gamma }^{2}+\alpha \delta \right)\tau \Delta \right)-\left(4b\left({\gamma }^{2}+2\alpha \delta \right)-2\alpha {\upsilon }^{2}\right){\mu }_{m}}{5\alpha \gamma \upsilon }\), then

and

Based on above results, \(E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{D*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{S*}\right]\le 0\) and \(E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{D*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{S*}\right]\le 0\).

Hence, Proposition 3 is proved.

Proof of Proposition 4

For the comparison between two single collection channels with the manufacturer as the collector and the third party as the collector, we get equivalent return quantity as \({\widehat{q}}_{t}=2q+\alpha {p}_{t}+2\gamma Q+{\epsilon }_{t}\) and \({\widehat{q}}_{m}=2q+\alpha {p}_{t}+2\gamma Q+{\epsilon }_{m}\) and obtain.

If \(a\ge \frac{4\left(4b\alpha \delta -9b{\gamma }^{2}-\alpha {\upsilon }^{2}\right){\mu }_{m}+\alpha \left(4b\delta -{\upsilon }^{2}\right)\left(\alpha \tau \Delta -q\right)-3\left(4b\alpha \delta -8b{\gamma }^{2}-\alpha {\upsilon }^{2}\right){\mu }_{t}-\left(12\gamma \tau \Delta -\upsilon {c}_{m}\right)b\alpha \gamma }{\alpha \gamma \upsilon }\), then

and

Based on the above results, \(E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{m*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{r}^{t*}\right]\ge 0\) and \(E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{m*}\right]-E\left[{\pi }_{m}^{t*}\right]\ge 0\).

Hence, Proposition 4 is proved.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaula, A.K., Jha, J.K. Pricing strategy with quality improvement in a dual collection channel closed-loop supply chain under return uncertainty. Oper Res Int J 24, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-024-00836-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12351-024-00836-7