Abstract

A 57-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of frequent hematochezia. Colonoscopy exhibited a submucosal tumor-like lesion in the lower rectum. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a rectal arteriovenous malformation (AVM) on the right side wall of the lower rectum. The feeder was the superior rectal artery, with early venous return. Embolization of the draining vein and feeding artery of the AVM with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate under balloon occlusion was planned. Angiography of the superior rectal artery showed the nidus in the rectum with early venous return of contrast material. The portal vein was punctured percutaneously under ultrasound guidance, and a balloon catheter advanced to the distal part of the superior rectal vein. Venography under balloon occlusion showed the outflow vein and nidus. Transvenous and transarterial nidus embolization with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate under balloon occlusion was then performed. Since the embolization, there have been no further episodes of bleeding. There is no established treatment for AVMs. Successful treatment requires targeting and eradication of the nidus. We successfully performed embolization therapy for a rectal AVM via a retrograde transvenous approach. This technique may be suitable for completely eradicating the nidus without the risk of embolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intestinal arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are a common cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding [1, 2]. AVMs have generally been treated surgically, either by ligation of the afferent arteries or by attempts at excision. Less invasive treatments such as endoscopic treatment and transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) have been reported; however, additional treatment may be required for recurrence after treatment with these modalities [3, 4]. We report here a case of successful embolization therapy for a rectal AVM via a balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous approach.

Case report

A 57-year-old man was admitted to our hospital because of painless hematochezia after defecation. He had facial and conjunctival pallor consistent with anemia. His medical history included a coronary intervention for myocardial infarction, and he was taking two antiplatelet drugs. Blood tests showed a mild microcytic and hypochromic anemia.

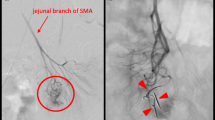

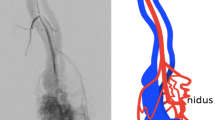

Colonoscopy revealed a pulsating submucosal tumor-like lesion in the lower rectum (Fig. 1a, b). Tortuous enlarged blood vessels were visible on surface of the mucous membrane. The lesion was suspected to be the cause of bleeding; however, no active bleeding was observed during colonoscopy. An abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) showed a collection of dilated blood vessels on the right side wall of the lower rectum. The feeder was the superior rectal artery (SRA), with early venous return (Fig. 2a–c). Given that hemostasis had occurred spontaneously, we decided to perform elective angiography and embolization. During the hospitalization, he had a further episode of hemorrhage and spontaneous hemostasis and required a blood transfusion for his anemia. After discontinuation of the antiplatelet drugs and heparinization, angiography was performed for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment on the seventh day of hospitalization. Angiography of the SRA showed vascular hyperplasia and nidus (Fig. 3a, b), resulting in a definitive diagnosis of a rectal AVM. A percutaneous transhepatic portal vein puncture was performed under ultrasound guidance and a catheter advanced to the distal part of the superior rectal vein (SRV). Venography under balloon occlusion showed the outflow vein and nidus with stasis of blood flow. To achieve an adequate embolic effect, the balloon was dilated upstream of the inflowing artery to reduce arterial blood flow, after which 20% NBCA–lipiodol (1:4) was slowly and retrogradely injected intravenously to embolize the nidus (Fig. 3c). Because a remaining vestige of the vascular malformation was detected by SRA after the retrograde transvenous obliteration procedure, TAE under balloon dilatation in the SRA was performed with 20% NBCA–lipiodol (Fig. 3d). Angiography performed via the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) confirmed that the nidus had disappeared and the early venous return resolved. Following embolization of this patient’s rectal AVM, his bleeding on defecation stopped completely, his symptoms of anemia improved, and his hemoglobin concentration returned to within the normal range. He was discharged on the 11th postoperative day without any adverse events or rebleeding. Lower gastrointestinal endoscopy and CECT performed one month after discharge revealed submucosal tumor-like ridges but no pulsation, sufficient lipiodol accumulation in the region that the AVM had been in, and resolution of the early return of the rectal vein in the arterial phase disappeared (Fig. 4a–c). Six months after the embolization, no further bleeding had occurred.

a Angiography via the IMA (blue arrow, upper panel). SRA were visualized (white arrow, under panel). b Angiography via the SRA (white arrow, lower panel). The nidus and an outflow vein, SRV (arrowhead, upper panel) were visualized. c Venography via the SRV (arrowhead) under balloon occlusion showed outflow vein and nidus; 20% NBCA–lipiodol was retrogradely injected intravenously to embolize the nidus. d Angiography via the SRA after embolization. Only a vestige of the vascular malformation was detected (yellow arrow); additional arterial embolization was therefore performed

Discussion

An AVM is an abnormal connection between arteries and veins that bypasses the capillary system. Histopathologically, AVMs in the gastrointestinal tract are characterized by diffuse vasodilation in all layers from the submucosal to the serosal layer and are composed of an inflow artery (feeder), an abnormal blood vessel assembly (nidus), and an outflow vein (drainer) [5, 6]. Patients typically present with intermittent bloody stools without abdominal pain, and anemia; the differential diagnosis is chronic hemorrhage from diverticulae. The lesions are most often located in the right hemicolon (37%), followed by the jejunum (24%), and ileum (19%), rectal lesions being rare (8%) [4].

AVMs are generally treated by surgical excision of the nidus. However, being highly invasive, this procedure may be contraindicated in older patients who are in poor general condition. In addition, if the lesion is located in the rectum, as in the present case, a permanent colostomy is required, prejudicing the patient’s quality of life. One alternative approach to small lesions is endoscopic hemostasis with clips and coagulation [4]. However, achieving hemostasis by this means is reportedly difficult and, even when it has been achieved, and the recurrence rate is high because it is not easy to reliably block the inflow artery of an AVM via an endoscopic approach [3].

An Interventional Radiology (IVR) method is efficient because it can achieve both diagnosis and treatment of AVMs. Embolization of an AVM requires complete embolization of the nidus without causing infarction of the organ [7]. If only the inflowing artery is embolized, development of collateral vessels is promoted, resulting in reestablishment of blood flow and reconstruction of a nidus [8, 9]. Therefore, recurrences also occur after TAE, resulting in it being considered a palliative form of treatment [10, 11]. There have been nine reports of intestinal AVMs treated with IVR in Japan. Although different embolic substances were used, all patients underwent TAE, and three of the nine (33%) subsequently had recurrences (Table 1) [3, 11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. There are some reports of TAE performed outside of Japan, but most of them are performed as neoadjuvant embolization, with TAE followed by surgery for radical cure [19, 20]. In addition, when embolic material passes through the nidus during arterial embolization, there is a risk of infarction occurring in other organs. In the present case, we considered that there would be a risk of hepatic ischemia if the embolic substance escaped into the blood vessels of the portal system, whereas transvenous nidus embolization after arrest of blood flow by a balloon might prevent unintentional embolism to, and ischemia of, other organs. The combined use of transvenous and transarterial embolization could achieve more complete eradication of the nidus and therefore prevent recurrence.

In conclusion, we consider that embolization of a rectal AVM by a retrograde transvenous approach may achieve complete eradication of the nidus without the adverse event of unexpected embolism.

References

Meyer CT, Troncale FJ, Galloway S, et al. Arterovenous malformation of the bowel: an analysys of 22 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1981;60:36–48.

Trudel JL, Fazio VW, Sivak MV. Colonoscopic diagnosis and treatment of arteriovenous malformation in chronic lower gastrointestinal bleeding: clinical accuracy and efficacy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:107–10.

Yasui T, Oyama K, Nakano T. A case of rectal arteriovenous malformation treated successfully with transarteral embolization. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2007;49:1433–9.

Kobayashi K, Igarashi M, Katsumata B, et al. Anteriovenous malformation of the intestine: review of 230 cases reported in Japan. Stomach Intest. 2000;35:753–61.

Moore JD, Thompson NW, Appelman HD, et al. Arteriovenous malformation of the gastrointentestinal tract. Arch Surg. 1976;111:381–9.

Iwashita A, Oishi T, Yao T, et al. Pathological differential diagnosis of vascular diseases of gastrointestinal tract. Stomach Intest. 2000;35:771–84.

Goto K, Ito O. Embolization of cerebral areteriovenous malformation present status and near future. Stroke. 1999;21:473–6.

Palmaz J, Newton T, Reiuter S, et al. Particulate intraarterial embolization in pelvic arteriovenous malformation. AJR. 1981;137:117–22.

Catherine E, Joseph P, Daniel M, et al. Balloon-occluded retrogrda transvenous obliteration of a gastric vascular malformation: an innovative approach to treatment of a rare condition. Cardiovasc Intervent. 2017;40:310–4.

Mallios A, Laurian C, Houbballah R, et al. Curative treatment of pelvic arteriovenous malformation-an alternative strategy: transvenous intra-operative embolization. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:548–53.

Sho I, Shoichiro M, Yuzo H, et al. Rectal arteriovenous malformation treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2020;14:7–14.

Sekine C, Matsui S, Iwamatsu H, et al. A case report of arteriovenous malformation of the transverse colon treated successfully by transcateter arterial embolization. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2003;45:1144–9.

Tsutikawa T, Hasegawa N, Sugano N, et al. A case of arteriovenous malformation of the colon resected by right colectomy after repeated treatment with arterial embolization. J Japan Surg Assoc. 2003;64:1939–43.

Okura K, Sekoguti T, Yuasa H, et al. A case report of arteriovenous malformation of the ascending colon treated successfully by transcatheter arterial embolization. J Abdom Emerg Med. 2007;27:731–4.

Yamada N, Okuyama Y, Tomatsuri N. A case of colorectal arteriovenousu malformation treated by embolization. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2010;52:1438–9.

Fujisawa T, Nishikawa M, Ueyama S, et al. Colonic areterovenous malformation with the diagnosis based on video capsule endoscopy: report of a case. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2012;54:275–80.

Matsuura G, Mukai S, Nakamura S, et al. A case of rectal areteriovenous malformation treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2014;56:49–55.

Komekami Y, Konishi F, Makita K, et al. Rectal arteriovenous malformation with bleeding of an internal hemorrhoid. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:22–6.

Liu KL, Lee CW, Wang HP, et al. Pre-operative localization and embolization for jejunal arteriovenous malformation with massive haemorrhage. Br J Radiol. 2007;80:159–61.

Pierce J, Matthews J, Stanley P, et al. Perirectal arteriovenous malformation treated by angioembolization and low anterior resection. J Pediater Surg. 2010;45:1542–5.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Trish Reynolds, MBBS, FRACP, from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

No specific grants from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors were received for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights

All procedures followed have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

The patients gave informed consent to publication of details of his case.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jubashi, A., Yamaguchi, D., Nagatsuma, G. et al. Successful retrograde transvenous embolization under balloon occlusion for rectal arteriovenous malformation. Clin J Gastroenterol 14, 594–598 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-020-01335-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-020-01335-w