Abstract

Introduction

Bipolar I disorder (BD-I) is associated with an increased risk of obesity, but few studies have evaluated the real-world clinical, humanistic, and economic effects associated with obesity in people with BD-I.

Methods

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of responses to the 2016 and 2020 National Health and Wellness surveys. Respondents (18–64 years) with a self-reported physician diagnosis of BD-I were matched to controls without BD-I based on demographic and health characteristics. Respondents were categorized by body mass index as underweight/normal weight (< 25 kg/m2), overweight (25 to < 30 kg/m2), or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2). Multivariable regression models were used to compare obesity-related comorbidities, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity, and indirect and direct costs.

Results

Before matching, the BD-I cohort was younger than the non-BD-I cohort and included more female and white respondents and a greater proportion covered by Medicaid or Medicare. After matching, the BD-I and non-BD-I cohorts had similar characteristics. A total of 5418 respondents (BD-I, n = 1806; matched controls, n = 3612) were analyzed. Obese respondents with BD-I reported the highest adjusted prevalences of high blood pressure (50%), high cholesterol (35%), sleep apnea (27%), osteoarthritis (17%), type 2 diabetes (12%), and liver disease (4%). Obesity in respondents with BD-I was associated with the lowest HRQoL scores. Measures of work impairment were highest in respondents with BD-I and obesity, as was HCRU. Respondents with BD-I and obesity had the highest associated total indirect and direct medical costs ($25,849 and $44,482, respectively).

Conclusion

Obese respondents with BD-I had greater frequencies of obesity-related comorbidities, higher HCRU, lower HRQoL, greater work impairments, and higher indirect and direct medical costs. These findings highlight the real-world burden of obesity in people with BD-I and the importance of considering treatments that may reduce this burden.

Plain Language Summary

Bipolar I disorder (or BD-I) is a serious mental illness that is associated with an increased risk of obesity. Only a few studies have looked at the real-world effects of obesity in people living with BD-I. We used responses from the 2016 and 2020 National Health and Wellness surveys to look at these real-world effects. We matched survey respondents so that those with BD-I had similar characteristics to those without BD-I. We also categorized the respondents by body mass index (underweight/normal weight, overweight, or obese). Then, we compared them across different outcomes. These effects were obesity-related medical conditions, quality-of-life measures, and different types of costs. We found that obese respondents with BD-I had the highest frequencies of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, sleep apnea (a condition where breathing stops while sleeping), osteoarthritis (a condition where joint tissues, such as in the knee or hip, break down over time), type 2 diabetes, and liver disease, along with the lowest scores for health-related quality of life. Obese respondents with BD-I had the highest work impairment scores, and the highest numbers of hospital visits, emergency department visits, and doctor visits in the 6 months before the survey. Finally, obese respondents with BD-I had the highest total costs related to work impairment and to medical care. This study reports the real-world effects of obesity in people living with BD-I. It is important to consider treatments for BD-I that may reduce these unfavorable effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

People living with bipolar I disorder (BD-I) are at an increased risk of obesity. |

This study examined real-world data to better understand and characterize the burden of BD-I and obesity across clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes. |

What was learned from the study? |

Respondents with BD-I and obesity had an increased prevalence of medical comorbidities, higher work impairment and healthcare resource utilization, lower health-related quality of life, and higher indirect and direct medical costs. |

These findings highlight the real-world burden of obesity in people with BD-I across clinical, humanistic, and economic domains and the importance of considering treatments that reduce this burden. |

Introduction

Bipolar I disorder (BD-I) is a serious mental illness characterized by recurrent episodes of mania and depression or mixed mood states [1]. The clinical burden of BD-I is significant because of the presence of potentially severe symptoms and psychiatric comorbidities [2]. Moreover, BD-I is associated with an increased risk of obesity and cardiometabolic conditions such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke [3, 4].

Several factors are thought to contribute to this increased risk of obesity, including those related to genetics and lifestyle [5,6,7]. Pharmacotherapies may also contribute to obesity in this population, because many agents used for controlling the symptoms of BD-I, including antipsychotic medications, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers, are associated with weight gain [8, 9].

Living with BD-I also affects other aspects of a person’s health and well-being [10]. Evidence suggests that BD-I is associated with increased healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and higher medical costs [3, 4, 11]. Weight gain experienced during the course of the disease and its treatment may have negative effects on these outcomes [12, 13]. For example, antipsychotic-associated weight gain is often cited as a bothersome adverse effect that affects daily functioning [10, 14]. It may also lead some people with BD-I to discontinue their medication, raising the risk of costly episodes of relapse and hospitalization [15,16,17].

Although weight gain and resultant increases in body mass index (BMI) may add to disease burden, the real-world effects associated with obesity in people living with BD-I are not well understood [18]. In this study, we assessed the burden of BD-I across BMI categories in terms of clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes in comparison with matched controls without BD-I.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of responses obtained from adults who participated in the National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) in 2016 and 2020. The NHWS is a self-administered internet-based survey conducted annually among a nationally representative sample of adults in the USA based on age, sex, and race. Data from the 2016 and 2020 NHWS were selected for analysis because respondents provided information about bipolar disorder subtype (e.g., BD-I vs bipolar II disorder) in those years. The survey includes questions on patient-reported health outcomes, HCRU, and medical conditions.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN); an exempt status was obtained for this study per Federal Regulation 45 CFR Subtitle A, Subchapter A, Part 46, Subpart A, §46.104(d)(2), which governs deidentified survey data [19].

Participants

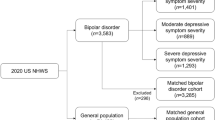

Respondents aged 18 to 64 years residing in the USA and completing either the 2016 or 2020 NHWS were eligible. Those who self-reported a physician diagnosis of BD-I were included in the BD-I cohort, and those who did not were included in the unmatched sample cohort (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for inclusion criteria). Respondents with BD-I were matched to controls using 1:2 greedy propensity-score matching based on age, sex, race, region, alcohol use, smoking status, exercise frequency, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). Matching was stratified by year of NHWS completion (2016 or 2020), age group (18–30, 31–45, or 46–64 years), and BMI (underweight/normal weight, < 25 kg/m2; overweight, 25 to < 30 kg/m2; or obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2). BMI was calculated from respondents’ self-reported height and weight. A total of 47 respondents with BD-I had missing variables and were excluded from propensity-score matching.

Primary Analysis

After matching was conducted, respondents were categorized and outcomes were assessed according to the BMI categories underweight/normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25 to < 30 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2). Clinical outcomes included the prevalences of self-reported obesity-related medical comorbidities, including the presence of high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular events (ministroke, stroke, heart attack, or congestive heart failure), asthma, liver disease, cancer, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea. Healthcare resource utilization, including hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and visits to healthcare professionals in the past 6 months, was also assessed.

Humanistic effects (i.e., health-related quality of life [HRQoL]) were evaluated using the 36-item Short Form Version 2 (SF-36v2) and EuroQol EQ-5D health surveys. Scores on the Mental Component Summary and Physical Component Summary of the SF-36v2 were calculated using a norm-based scoring algorithm with linear T-score transformation and then scaled to 100. On both the SF-36v2 and the EQ-5D, lower scores represent worse HRQoL. For the SF-36v2, a clinically meaningful difference in Mental Component Summary score is 3 points [20], and estimates of the clinically meaningful difference for the EQ-5D range from 0.03 to 0.52 points among different patient populations [21,22,23].

From an economic standpoint, work productivity was evaluated via the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment (WPAI) questionnaire, which is composed of four assessments: absenteeism (missed work in the past 7 days), presenteeism (lost productivity at work in the past 7 days), overall work impairment (absenteeism and presenteeism in the past 7 days combined), and activity impairment (health-related impairment in daily activities in the past 7 days). Only respondents who reported being employed at the time of the survey provided responses to questions about absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment; all respondents answered questions about activity impairment. Estimates of total indirect costs, including indirect costs associated with absenteeism and presenteeism, were derived from 2019 hourly wage data published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics [24]. Direct medical costs were estimated using data from the 2018 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey and based on national cost averages for each type of resource utilized [25].

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable regression models were used to assess differences in outcomes between subgroups. In addition, NHWS year (2016 vs 2020) was included as a covariate in regression models to control for the potential effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on outcomes. Frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical outcomes, whereas SDs/SEMs were reported for continuous outcomes. Study outcomes were summarized descriptively, with no reported formal hypothesis testing between subgroups.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted with obesity further stratified into the following subgroups: underweight/normal weight, overweight, obese class 1 (BMI 30 to < 35 kg/m2), obese class 2 (BMI 35 to < 40 kg/m2), and obese class 3 (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2).

Results

Respondent Demographics

A total of 123,935 respondents completed the 2016 or 2020 NHWS. Of these, 1806 reported having a physician diagnosis of BD-I and were included in the BD-I cohort, while 122,129 respondents did not and were included in the unmatched sample (Table 1).

Before matching, the BD-I cohort was younger than the non-BD-I cohort (mean [SD] = 38.7 [12.3] vs 41.3 [13.6] years) and included more female (65.4% vs 57.8%, respectively) and white (62.1% vs 58.8%, respectively) respondents. In addition, respondents with BD-I were less often married or living with a partner (45.3% vs 54.8%, respectively) and less likely to have commercial insurance coverage (35.2% vs 70%, respectively). The proportions of respondents covered by Medicaid or Medicare were higher in the BD-I cohort compared with the non-BD-I cohort (23.9% vs 8.4% and 22.9% vs 6.7%, respectively). Also, respondents with BD-I were more likely than those in the non-BD-I cohort to report being a current smoker (45.3% vs 14.2%, respectively).

After propensity-score matching, a total of 5418 respondents (BD-I, n = 1806; matched controls, n = 3612) were included in the analysis. Propensity-score matching was successful; the BD-I and non-BD-I cohorts were similar in terms of age, sex, race, region, alcohol use, smoking status, exercise frequency, and modified CCI (Table 1).

Medical Comorbidities and HCRU

Respondents with BD-I who were obese had the highest adjusted prevalence rates of high blood pressure (50%), high cholesterol (35%), and sleep apnea (27%) (Fig. 1). Adjusted prevalence estimates of osteoarthritis (17%), type 2 diabetes (12%), and liver disease (4%) were also highest in respondents with BD-I and obesity. Cardiovascular event prevalence was highest for respondents who were overweight; however, the prevalences were similar between those with BD-I (17%) and matched controls (16%). Prevalence estimates for asthma were highest for respondents with BD-I who were overweight (28%); 22% of obese patients with BD-I had asthma.

Adjusted proportionsa of self-reported medical comorbidities in respondents with BD-I versus matched controls by BMI category. aAdjusted for age, sex, race, residence type, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHWS year. bIncludes ministroke, stroke, heart attack, and congestive heart failure. BD-I bipolar I disorder, BMI body mass index, CV cardiovascular, NHWS National Health and Wellness Survey

In the 6 months before survey completion, HCRU was highest in obese respondents with BD-I (Fig. 2). In respondents with BD-I and obesity, the mean (SEM) numbers of hospitalizations and ED visits were 0.80 (0.18) and 1.87 (0.29), respectively. The number of visits to any healthcare professional was also highest in respondents with BD-I and obesity, with a mean (SEM) of 12.70 (0.99).

Adjusted HCRU in previous 6 months.a aAdjusted for age, sex, race, residential type, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHWS year. BD-I bipolar I disorder, BMI body mass index, ED emergency department, HCP healthcare professional, HCRU healthcare resource use, NHWS National Health and Wellness Survey

Health-Related Quality of Life

Obese respondents with BD-I reported the lowest mental health and HRQoL scores on the SF-36v2 and the EQ-5D (Fig. 3). The mean (SEM) SF-36v2 Mental Component Summary score for obese respondents with BD-I was 31.1 (0.84). The mean (SEM) score on the SF-36v2 Physical Component Summary was lowest for obese respondents, but the scores in both obese respondents with BD-I (40.4 [0.65]) and their matched controls (40.6 [0.62]) were similar. Overall HRQoL, as assessed by the EQ-5D, was lowest among the obese subgroup of respondents with BD-I, with a mean (SEM) score of 0.57 (0.01).

Adjusted HRQoL scores.a aAdjusted for age, sex, race, residential type, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHWS year. bLower scores represent worse health status. cScaled to 100. BD-I bipolar I disorder, BMI body mass index, HRQoL health-related quality of life, MCS Mental Component Summary, NHWS National Health and Wellness Survey, PCS Physical Component Summary, SF-36v2 36-item Short Form Version 2

Work Productivity and Indirect Costs

A total of 792 respondents with BD-I and 1544 matched controls were employed at the time of the survey and provided data on the work-related items of the WPAI questionnaire (Fig. 4). Mean (SEM) absenteeism scores were highest for respondents with obesity; the scores for obese respondents with BD-I (44.3 [6.59]) and their matched controls (45.6 [6.77]) were similar. Obese respondents with BD-I had the highest mean (SEM) scores for presenteeism (60.6 [4.89]) and overall work impairment (71.2 [5.83]). The mean (SEM) score for activity impairment was highest in those with BD-I and obesity (64.5 [2.47]).

Adjusted WPAI questionnaire scores.a,b aAdjusted for age, sex, race, residential type, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHWS year. bHigher scores represent greater work-related impairment. BD-I bipolar I disorder, BMI body mass index, NHWS National Health and Wellness Survey, WPAI Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

BD-I with comorbid obesity was associated with the highest adjusted mean [SEM] cost estimates from absenteeism ($15,313 [$2413]) and of total indirect costs ($25,849 [$2750]) (Fig. 5). Annual cost estimates for presenteeism were numerically highest among respondents with BD-I who were overweight ($15,632 [$2397]) or obese ($14,761 [$1698]).

Adjusted indirect and direct costs (in USD), annualized.a aAdjusted for age, sex, race, residential type, marital status, education, employment status, insurance status, smoking status, alcohol use, exercise frequency, modified Charlson Comorbidity Index, and NHWS year. bAnalyzed using a zero-inflated model with a negative binomial distribution. cAnalyzed using a generalized linear model with a negative binomial distribution. BD-I bipolar I disorder, BMI body mass index, ED emergency department, HCP healthcare professional, NHWS National Health and Wellness Survey, USD US dollars

Direct Costs

BD-I with comorbid obesity was associated with the highest adjusted mean [SEM] direct medical costs for ED visits ($7931 [$731]) and for visits to any healthcare professional ($8582 [$575]) (Fig. 5). Total direct medical costs per year were estimated to be highest for respondents with BD-I and obesity ($44,482 [$4561]) compared with matched controls with obesity ($29,189 [$2846]).

Sensitivity Analysis

In the sensitivity analysis with obesity stratified by class, the burden associated with obesity tended to increase with BMI (see Supplementary Fig S2 and S3 for details). As a result, those with BD-I who were in obese class 3 had the highest adjusted prevalences of several medical comorbidities, as well as the highest estimates of total direct costs.

Discussion

In this study of patient-reported data from the NHWS, obesity was associated with several clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes that may broadly and negatively affect the lives of people living with BD-I.

After adjustment for demographic and health characteristics, obese respondents with BD-I had the highest prevalence estimates of high blood pressure, hypercholesterolemia, type 2 diabetes, liver disease, osteoarthritis, and sleep apnea among all subgroups evaluated. Adjusted prevalence estimates of asthma were highest in patients with BD-I who were overweight or obese. In addition, prevalence estimates for cardiovascular events were highest for respondents who were overweight, regardless of the presence or absence of BD-I. Overall, obese respondents with BD-I had increased HCRU, as exemplified by the highest average numbers of hospitalizations, ED visits, and visits to any healthcare professional in the 6 months before completing the survey.

Although overweight and obesity were related to a higher risk of comorbidities, lower overall HRQoL, and lower physical health outcomes, BMI was not linearly related to mental health outcomes in either the BD-I or matched control cohort. For both cohorts, those with obesity scored the lowest on mental health outcomes overall. However, the differences among BMI categories were small and not considered clinically meaningful. Instead, it appears that the more impactful difference in mental health scores between the BD-I and matched control cohorts was the presence of BD-I. These results suggest that obesity may impact physical health outcomes more directly in the presence or absence of BD-I but might have a lesser overall effect on mental health outcomes.

Among respondents who were employed at the time of the survey, BD-I with comorbid obesity was associated with greater losses of work productivity resulting from presenteeism and with higher scores of overall work impairment. Health-related activity impairment in the previous 7 days was also reported to be highest in respondents with BD-I and obesity. As a result of higher work productivity loss and greater HCRU, respondents with BD-I and obesity had the highest total indirect and direct medical costs of all the subgroups.

The results of this analysis align and extend the findings of previous studies that reported on the burden of BD-I and obesity on clinical, humanistic, and economic outcomes [3, 12, 26]. Compared with the general population, people living with BD-I are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality resulting from cardiovascular disease [4, 27]. A significant risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease is increased body weight, and obesity is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and premature mortality [27,28,29]. The presence of obesity-related comorbidities in people with BD-I has been reported to increase HCRU and associated medical costs [3, 30,31,32].

Although genetic and lifestyle factors play roles in the increased risk of obesity in patients with BD-I, many medications used to manage the symptoms of BD-I also confer a risk for treatment-associated weight gain [5,6,7,8,9]. Previous studies have reported that treatment-associated weight gain is among the most common and bothersome adverse effects of antipsychotic medications [10, 14]. Increases in body weight during the course of treatment may have negative effects on work and social functioning and may persist despite discontinuation or switching of medications [14, 18]. The outcomes observed in this study help to identify important future areas of research in this regard, such as how antipsychotic medications may influence the association between obesity and patient well-being. These findings can inform the development of treatment strategies that better align with patient priorities, potentially leading to improved disease management and overall health outcomes.

An important consideration in the management of BD-I is finding pharmacotherapies that minimize treatment-associated weight gain and adverse effects while maintaining symptom control. A current challenge in this regard is that patients and clinicians must often make tradeoffs between a medication’s benefits (e.g., clinical efficacy) and its risks (e.g., the potential for weight gain and other adverse effects) when choosing an antipsychotic treatment [33, 34]. The burden of adverse effects is particularly important, as they can impact patients’ willingness and ability to continue treatment [14]. Understanding the features of an antipsychotic medication that patients with BD-I value the most, and the adverse effects that they want to avoid, may encourage clinicians to prescribe treatments that align with their patients’ preferences.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study are worth noting. The NHWS is conducted annually among a nationally representative sample of US adults who are stratified on the basis of age, sex, and race, and therefore the results from this analysis may be generalizable to the larger population of obese people living with BD-I in the USA. The timeliness of NHWS data permitted us to analyze recent outcomes among people living with BD-I. The broad scope of demographic and health questions in the NHWS enabled comprehensive matching of survey respondents with BD-I to those without BD-I. Likewise, the availability of a wide range of patient-reported outcomes allowed for a robust analysis of the association between BD-I and obesity.

Some limitations that are inherent to the data source and study design apply. This analysis was cross-sectional. No causal links between the effect of BD-I or obesity on the outcomes reported herein can be made. The NHWS is a self-reported survey, so responses could not be validated and BD-I diagnoses could not be verified. Because respondents self-reported their weight status, inaccurate BMI categorizations and underestimation of the relationship between obesity and study outcomes are possible. Patient-reported assessments (e.g., WPAI, SF-36v2) may be subject to biases inherent to survey research methods, including recall bias [35, 36].

Conclusions

Living with BD-I is associated with significant clinical, humanistic, and economic burden, and, on the basis of these results, obesity adds to that burden. In this study, respondents with self-reported BD-I and obesity had an increased prevalence of medical comorbidities, higher HCRU, lower HRQoL, and higher indirect and direct medical costs. These findings highlight the real-world burden of obesity in people with BD-I across clinical, humanistic, and economic domains and the importance of considering treatments that reduce this burden.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to Cerner Enviza, an Oracle company, providing these data through a third-party license.

References

Goes FS. Diagnosis and management of bipolar disorders. BMJ. 2023;381:e073591.

Nabavi B, Mitchell AJ, Nutt D. A lifetime prevalence of comorbidity between bipolar affective disorder and anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of 52 interview-based studies of psychiatric population. EBioMedicine. 2015;2(10):1405–19.

Bessonova L, Ogden K, Doane MJ, O’Sullivan AK, Tohen M. The economic burden of bipolar disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:481–97.

Crump C, Sundquist K, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: a Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(9):931–9.

Baskaran A, Cha DS, Powell AM, Jalil D, McIntyre RS. Sex differences in rates of obesity in bipolar disorder: postulated mechanisms. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(1):83–92.

Goldstein BI, Liu SM, Zivkovic N, et al. The burden of obesity among adults with bipolar disorder in the United States. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(4):387–95.

Holt RI, Peveler RC. Obesity, serious mental illness and antipsychotic drugs. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(7):665–79.

Bak M, Fransen A, Janssen J, van Os J, Drukker M. Almost all antipsychotics result in weight gain: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94112.

McElroy SL. Obesity in patients with severe mental illness: overview and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 3):12–21.

Doane MJ, Raymond K, Saucier C, et al. Unmet needs with antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder: patient perspectives from qualitative focus groups. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):245.

Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 bipolar I disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions—III. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;84:310–7.

Doane MJ, Thompson J, Jauregui A, Gasper S, Csoboth C. Clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes associated with obesity among people with bipolar I disorder in the United States: analysis of National Health and Wellness Survey data. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2023;15:681–9.

Kolotkin RL, Corey-Lisle PK, Crosby RD, et al. Impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring Md). 2008;16(4):749–54.

Bessonova L, Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, et al. Antipsychotic treatment experiences of people with bipolar I disorder: patient perspectives from an online survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):354.

Doane MJ, Ogden K, Bessonova L, O’Sullivan AK, Tohen M. Real-world patterns of utilization and costs associated with second-generation oral antipsychotic medication for the treatment of bipolar disorder: a literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:515–31.

Weiden PJ, Mackell JA, McDonnell DD. Obesity as a risk factor for antipsychotic noncompliance. Schizophr Res. 2004;66(1):51–7.

Johnson FR, Ozdemir S, Manjunath R, et al. Factors that affect adherence to bipolar disorder treatments: a stated-preference approach. Med Care. 2007;45(6):545–52.

Doane MJ, Bessonova L, Friedler HS, et al. Weight gain and comorbidities associated with oral second-generation antipsychotics: analysis of real-world data for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):114.

US Department of Health and Human Services. §46.104 Exempt research. Code of Federal Regulations. 1982. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-45/subtitle-A/subchapter-A/part-46/subpart-A/section-46.104#p-46.104(d)(7).

Yarlas A, Rubin DT, Panés J, et al. Burden of ulcerative colitis on functioning and well-being: a systematic literature review of the SF-36® Health Survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(5):600–9.

Coretti S, Ruggeri M, McNamee P. The minimum clinically important difference for EQ-5D index: a critical review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14(2):221–33.

Del Corral T, Fabero-Garrido R, Plaza-Manzano G, et al. Minimal clinically important differences in EQ-5D-5L index and VAS after a respiratory muscle training program in individuals experiencing long-term post-COVID-19 symptoms. Biomedicines. 2023;11(9):2522.

Zheng M, Hakim A, Konkwo C, et al. Advancing diagnosis and management of liver disease in adults through exome sequencing. EBioMedicine. 2023;95:104747.

US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Highlights of women's earnings in 2019. Report 1089. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2020. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2019/home.htm. Accessed 6 Sept 2022.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mean expenditure per event by event type and age groups, United States. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2018. https://datatools.ahrq.gov/meps-hc. Accessed 19 Oct 2022.

Bond DJ, Kunz M, Torres IJ, Lam RW, Yatham LN. The association of weight gain with mood symptoms and functional outcomes following a first manic episode: prospective 12-month data from the Systematic Treatment Optimization Program for Early Mania (STOP-EM). Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(6):616–26.

De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77.

Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129(25 Suppl 2):S102–38.

McElroy SL, Keck PE Jr. Obesity in bipolar disorder: an overview. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(6):650–8.

Centorrino F, Mark TL, Talamo A, Oh K, Chang J. Health and economic burden of metabolic comorbidity among individuals with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(6):595–600.

Correll CU, Ng-Mak DS, Stafkey-Mailey D, et al. Cardiometabolic comorbidities, readmission, and costs in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a real-world analysis. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:9.

Guo JJ, Keck PE Jr, Li H, Jang R, Kelton CM. Treatment costs and health care utilization for patients with bipolar disorder in a large managed care population. Value Health. 2008;11(3):416–23.

Katz EG, Hauber B, Gopal S, et al. Physician and patient benefit-risk preferences from two randomized long-acting injectable antipsychotic trials. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2127–39.

Markowitz MA, Levitan BS, Mohamed AF, et al. Psychiatrists’ judgments about antipsychotic benefit and risk outcomes and formulation in schizophrenia treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(9):1133–9.

Prusoff BA, Merikangas KR, Weissman MM. Lifetime prevalence and age of onset of psychiatric disorders: recall 4 years later. J Psychiatr Res. 1988;22(2):107–17.

Wittchen HU, Burke JD, Semler G, et al. Recall and dating of psychiatric symptoms. Test-retest reliability of time-related symptom questions in a standardized psychiatric interview. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(5):437–43.

Acknowledgements

We thank the NHWS participants.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Omar H. Cabrera, PhD, and John H. Simmons, MD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Alkermes, Inc.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Alkermes, Inc. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Alkermes, Inc. Alkermes, Inc., also funded the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access fees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Michael J. Doane contributed to conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, original draft preparation, review and editing, and supervision. Adam Jauregui contributed to formal analysis and investigation, original draft preparation, and review and editing. Hemangi R. Panchmatia contributed to formal analysis and investigation and review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Michael J. Doane and Hemangi R. Panchmatia are or were employees of Alkermes, Inc., and may own stock/options in the company. Adam Jauregui is or was employed by Cerner Enviza, an Oracle company, which received payment from Alkermes, Inc., for participation in conducting this research.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles derived from the Declaration of Helsinki. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Pearl Institutional Review Board (Indianapolis, IN); an exempt status was obtained for this study per Federal Regulation 45 CFR Subtitle A, Subchapter A, Part 46, Subpart A, §46.104(d)(2), which governs deidentified survey data.

Additional information

Prior Presentation: Portions of this work were previously presented in posters at AMCP-Nexus 2023, Orlando, FL, Oct 16–19, 2023; Psych Congress 2023, Nashville, TN, Sep 6–10, 2023; and 2023 Neuroscience Education Institute Congress, Colorado Springs, CO, Nov 9–12, 2023.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doane, M.J., Jauregui, A. & Panchmatia, H.R. Matched Comparison Examining the Effect of Obesity on Clinical, Economic, and Humanistic Outcomes in Patients with Bipolar I Disorder. Adv Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02953-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02953-3