Abstract

The management of patients affected by moderate-to-severe psoriasis may be challenging, in particular in patients with serious infectious diseases [tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B and C, HIV, COVID-19]. Indeed, these infections should be ruled out before starting and during systemic treatment for psoriasis. Currently, four conventional systemic drugs (methotrexate, dimethyl fumarate, acitretin, cyclosporine), four classes of biologics (anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha, anti-interleukin (IL)12/23, anti-IL-17s, and anti-IL-23], and two oral small molecules (apremilast, deucravacitinib) have been licensed for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Each of these drugs is characterized by a unique safety profile which should be considered before starting therapy. Indeed, some comorbidities or risk factors may limit their use. In this context, the aim of this manuscript was to evaluate the management of patients affected by moderate-to-severe psoriasis with serious infectious diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

The management of patients affected by moderate-to-severe psoriasis may be challenging, in particular in patients with serious infectious diseases. |

Therefore, the infectious risk as well as the presence of a severe infectious disease should be considered in treatment decisions. |

What was learned from the study? |

Patients should be screened for tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV before starting the majority of systemic treatments for psoriasis. |

Our review evaluated the management of patients affected by moderate-to-severe psoriasis with serious infectious disease. |

Each of the currently approved systemic drug for psoriasis (conventional systemic drugs, biologics, oral small molecules) is characterized by a unique safety profile which should be considered before starting therapy. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting up to 3% of the worldwide population, usually presenting as well-defined erythematous-desquamative plaques covered by whitish or silvery scales, predominantly found on elbows, knees, scalp, and the lumbar areas (plaque psoriasis, about 90% of cases) [1,2,3,4]. However, other clinical presentations can be distinguished such as guttate psoriasis, erythrodermic psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, and inverse psoriasis [1,2,3,4].

Recent knowledge on psoriasis has led to the consideration of this disorder as a systemic disease. Indeed, several comorbidities can be associated with psoriasis including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular diseases, neurological and psychiatric disorders, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, and endocrine disorders [5,6,7,8]. In this context, appropriate and well-designed treatment is needed, targeting not only the skin manifestations but the psoriatic disease as a whole.

Although mild psoriasis is usually well controlled with topical prescription therapies based on the combination of calcipotriol and betamethasone, the management of moderate-to-severe forms of the disease may be challenging [9, 10]. Indeed, conventional systemic treatments [methotrexate (MTX), dimethyl fumarate, acitretin, cyclosporine (CsA)] may be contraindicated in cases with comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, hepatic or renal failure, etc.) or risk of adverse events (AEs). Another therapeutic option is phototherapy, which may be limited by logistical issues [9, 10].

Recently, the introduction of biological drugs, specifically targeting interleukins (IL) involved in psoriasis pathogenesis, including anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-17s, and anti-IL-23s, have revolutionized the management of psoriatic disease, with an excellent profile in terms of safety [9, 10]. However, biologics may also have some considerations to be mindful of before initiating treatment, such as the use of anti-TNF-α, which is contraindicated in patients with multiple sclerosis and advanced hearth failure, the risk of reactivating latent infection, or triggering or worsening inflammatory bowel diseases (anti-IL-17 drugs) [11,12,13]. Indeed, routine blood tests should be performed before starting biological treatment, and the risk of hepatitis, tuberculosis, and HIV should be ruled out [11,12,13]. Finally, apremilast and deucravacitinib are two oral small molecules (OSM) approved for psoriasis management. Although apremilast has no contraindication for patients affected by severe infections, deucravacitinib has the same limitations as biological drugs [14, 15].

In this context, the aim of this study was to investigate the management of patients with serious infectious diseases who were affected by moderate-to-severe psoriasis. This review focuses on serious infectious disease [tuberculosis (TB), hepatitis B and C, HIV, COVID-19] which should be considered before starting and during systemic treatment for psoriasis. Moreover, a special focus on COVID-19 infection is discussed. Conventional OSM and biologics were considered, with a special emphasis on the latter. This manuscript is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Tuberculosis

TB is an infectious disease, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and is still one of the 10 leading causes of death worldwide [16]. TB is transmitted by air, through respiratory secretions released into the air by a contagious individual, for example through saliva, sneezing, or coughing. In immunocompetent hosts, the immune system is able to control the infection and an asymptomatic condition called latent tuberculous infection (LTBI) develops, which is estimated to affect about a quarter of the world's population [16]. It is estimated that 5–10% of individuals with LTBI, if untreated, develop active tuberculous disease during their lifetime [16]. The main risk factors for reactivation of LTBI include HIV infection, organ transplantation, silicosis, close contact with individuals with active TB, and the use of therapies that suppress or modulate the immune system [17].

Systemic therapies approved for the treatment of psoriasis, both conventional and biological, act by suppressing or modulating the activity of specific cells and/or cytokines that play a key role in the immune response, and thus are associated with possible reactivation of LTBI. Concerning conventional systemic agents, it should be noted that LTBI screening is not recommended in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) of acitretin, CsA, or fumarates [18,19,20]. However, whereas for acitretin and fumarates there have never been reports of LTBI reactivation [21, 22], for CsA, LTBI reactivation has been reported in patients undergoing organ transplantation and treated with high doses of the drug [21]. Screening for LTBI is recommended in the SmPC of MTX, and cases of LTBI reactivation during treatment with MTX have been reported [23, 24]. A new group of drugs for the treatment of psoriasis are OSM, including apremilast and deucravacitinib. Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has shown a good safety profile and can be used without risk of reactivation in patients with LTBI. Indeed, the apremilast clinical trials (ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2) also included seven patients with a history of previously treated Tb, of whom four had LTBI and were enrolled without prophylaxis before starting treatment with apremilast. No cases of Tb reactivation were detected in these patients [25].

Of note, unlike apremilast, screening for TB is required to start deucravacitinib therapy [26]. Among biological drugs, TNF-α inhibitors were the first to be approved for the treatment of psoriasis. Clinical trials and real-life data have amply demonstrated that therapy with anti-TNF-α is a high-risk factor for LTBI reactivation [27, 28]. Early randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on infliximab showed a fourfold increase in the risk of TB infection [29, 30]; subsequently, other studies reported an increased risk of TB in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists relative to a placebo group, with relative risk ranging from 1.6 to 25.1 [31]. Data in the literature show an increased risk of LTBI reactivation with infliximab and adalimumab, followed by etanercept. The increased risk of TB reactivation in patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors may be explained by the immune role of this cytokine. In fact, by increasing the phagocytic activity of macrophages and the production of reactive nitrogen and oxygen intermediates, TNF-α facilitates the intracellular killing of mycobacterium, synergistically with interferon gamma [32]. In addition, TNF-α is involved in the formation and maintenance of the tubercular granuloma, thus preventing the dissemination of mycobacteria in the bloodstream [33]. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting the shared p40 subunit of the cytokines IL-12 and IL-23, has been associated with cases of LTBI reactivation, probably related to the inhibition of IL-12, which plays an important role in the Th1 immune response against M. tuberculosis [34].

Clinical trials conducted on IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors found no safety concerns in relation to an increased risk of TB reactivation in patients with LTBI [35, 36]. In the IMMhance phase 3 clinical trial, 31 patients with LTBI at baseline were treated with risankizumab, an IL-23p19 inhibitor, and none of them developed TB reactivation at 55 weeks of follow-up [37]. In a real-life study of 10 patients with LTBI who did not undergo chemoprophylaxis and were treated with the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab, none of the patients developed TB reactivation during up to 84 weeks of follow-up [38]. Recently, Manzanares et al. conducted a retrospective multicentre study of 35 patients with untreated LTBI undergoing biological therapy for psoriasis with different drugs [risankizumab (21), guselkumab (5), tildrakizumab (5), ixekizumab (2), secukinumab (1), and brodalumab (1)]; no cases of TB reactivation were observed [39]. Finally, Torres et al. conducted a retrospective observational study of 405 patients with psoriasis and diagnosed LTBI treated with biological therapy, of whom 112 did not undergo chemoprophylaxis for LTBI. The authors showed only one case of TB reactivation in a patient with LTBI, who had not undergone chemoprophylaxis, after 14 months of treatment with ixekizumab. The TB reactivation rate was 0.46% and 0% for IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors, respectively [40].

Current guidelines recommend screening for TB infection before starting any biological therapy, regardless of the drug chosen [41]. Screening includes a complete history and physical examination, tuberculin skin test (TST) and/or interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) test, and chest X-ray. If a diagnosis of LTBI is made, anti-TB chemoprophylaxis should be carried out before starting biological therapy [41]. Several treatment regimens are available for the treatment of LTBI. Those most commonly used in clinical practice involve the use of isoniazid (INH) (5 mg/kg; max dose: 300 mg) for 6 months or INH (5 mg/kg; max dose: 300 mg) + rifampicin (RIF) (10 mg/kg; max dose: 600 mg) for 3 months, with the possibility of starting biological therapy after 1 month of chemoprophylaxis [42].

Hepatitis B and C

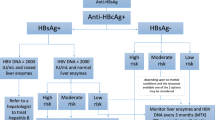

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by a DNA virus of the Hepadnaviridae family. Hepatitis B is a major global health problem. Indeed, it can cause chronic infection and puts people at high risk of death from cirrhosis and liver cancer [43]. The virus can spread through contact with infected body fluids like blood, saliva, vaginal fluids, and semen. It can also be passed from a mother to her baby. In adults, the disease become chronic in about 5–10% of cases. The risk of chronicity increases as the age at which the infection is acquired decreases; in fact, in infants infected shortly after birth, it occurs approximately nine times out of 10. Hepatitis C is caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which belongs to the Flaviviridae family. Transmission occurs mainly via the apparent and inapparent parenteral route. The initial acute HCV infection is in most cases asymptomatic; however, up to 85% of cases will become chronic. In addition, 20–30% of patients with chronic hepatitis C develop cirrhosis and, in approximately 1–4%, subsequent hepatocarcinoma [43]. Systemic therapies for psoriasis can lead to reactivation of chronic viral hepatitis by interfering with cytokines involved in the control of viral infection. Therefore, current guidelines recommend screening for hepatitis B and C before starting both conventional (MTX, CsA) and biological therapies for psoriasis [42]. In contrast, as already seen for LTBI, apremilast does not require screening for hepatitis B and C to initiate treatment. Laboratory screening should include evaluation of the following parameters: (1) for hepatitis B: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B core antibody (HbcAb), and anti-HBs, and in the case of positive HbsAg or HbcAb, also HBV DNA (hepatitis B virus); (2) for hepatitis C: anti-HCV, and by positivity, HCV-RNA [42].

In cases of active hepatitis B and/or C, the decision to undertake biological therapy must be evaluated in consultation with a hepatologist in order to assess the safest drug class and concomitant antiviral therapy [44]. In the case of inactive HBV carriers (HbsAg+, anti-HBc+, HBV DNA < 2000 IU/ml, normal transaminase levels) treated with high-to-moderate-risk immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. anti-TNF-α, ustekinumab, CsA), there is a risk of reactivation of viral infection, and patients should undergo prophylactic antiviral treatment with lamivudine or entecavir prior to the initiation of biological therapy. Conversely, inactive HBV carriers who are prescribed low-risk immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. MTX, acitretin, apremilast, IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors) need to be monitored for viral reactivation by determining alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and HBV DNA levels every 3 months [45, 46]. In the case of HbsAg negativity and HbcAb positivity, the choice of antiviral prophylaxis or quarterly monitoring of transaminases and viral markers can be made on the basis of HBV DNA positivity or negativity, possibly after consultation with a hepatologist and/or infectiologist and after considering the patient's risk factors [42]. Of note, HBV prophylaxis should be started at least 2 weeks prior to the administration of a biologic and continued for up to 6 months after discontinuation of the biologic [47]. Current guidelines recommend a hepatological consultation in the event of a positive screening for hepatitis C [42]. However, the risk of reactivation of latent infection (anti-HCV positivity and HCV-RNA negativity) appears to be lower for hepatitis C than for hepatitis B [48], and moreover, definitive and effective treatments for HCV infection are now available. Nevertheless, clinical trials and real-life studies show a significantly different risk of reactivation of hepatitis B and C for the several classes of systemic drugs used to treat psoriasis.

Concerning conventional systemic therapies, MTX has direct hepatic toxicity, and in most international guidelines, the use of MTX is contraindicated in HbsAg+ or HCV+ patients due to the risk of progression to fibrosis or cirrhosis [49,50,51]. However, there are conflicting opinions in the literature, as some real-life studies do not show an increased risk of fibrosis in patients with long-term MTX treatment [52]. Given the availability of alternatives, MTX is not a first choice of treatment in this patient setting today. Similarly, CsA has an important immunosuppressive effect and for this reason is not a first-line option for the treatment of psoriasis in patients with positive screening for HBV and/or HCV [47]. Finally, acitretin is associated with a low risk of reactivation of hepatitis B and C and may be considered a viable alternative in the absence of therapeutic options, with a better efficacy/safety profile for the treatment of psoriasis [42, 49]. As far as OSM are concerned, apremilast has an excellent safety profile, as it can also be used in patients with cancer or active infections, and does not require screening for HBV and HCV before starting therapy [53]. Unlike apremilast, screening for viral hepatitis is mandatory before starting deucravacitinib therapy. Among biological drugs, the risk of viral reactivation or opportunistic infections is reported to be higher with TNF-α inhibitors [54, 55]. Clinical trials show a higher risk of HBV reactivation for infliximab and adalimumab than for etanercept [56].

Given the importance of IL-12 in counteracting infections by intracellular pathogens, the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab is associated with an increased risk of HBV reactivation [57]. A 2018 meta-analysis of 28 HBV+ patients treated with ustekinumab and not receiving antiviral prophylaxis showed three cases of HBV reactivation [58]. However, there is growing evidence that IL-17 and, in particular, IL-23 inhibitors are less likely to cause HBV and HCV reactivation than anti-TNF-α [48, 59, 60]. Nevertheless, a multicentre study of 46 patients treated with secukinumab in the absence of antiviral prophylaxis recorded seven cases (15.2%) of HBV reactivation [61]. Several real-life studies, however, showed a very low risk of HBV reactivation in HbsAg+ patients treated with secukinumab and receiving concomitant antiviral prophylaxis [47]. Regarding HBcAb positivity with HbsAg and HBV DNA negativity, prophylaxis should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Conversely, in the absence of antiviral prophylaxis, the incidence of HCV reactivation is very low but still possible [62]. With regard to IL-23 inhibitors, the risk of reactivation of hepatitis B and C also appears to be very low. Several real-life studies have demonstrated the safety of guselkumab, risankizumab, and tildrakizumab in these patient settings [60, 63, 64]. In any case, the current guidelines provide the same recommendations as for the other biological classes [42].

HIV

Human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV-1 and HIV-2) belong to the genus Lentivirus, and the infection that they cause, if left untreated, is responsible for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [65]. HIV remains a major global public health issue, with an estimated 39.0 million [33.1–45.7 million] people living with HIV at the end of 2022 [66]. The prevalence of psoriasis in the HIV+ population ranges from 1 to 3%, a rate very similar to that in the general uninfected population [67]. The treatment of psoriasis in HIV-infected patients is challenging, given the profound state of immunosuppression that the infection causes. Psoriasis in HIV+ patients is often severe and resistant to first-line therapy represented by topical agents, phototherapy, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), and acitretin, which, while presenting no safety problems, prove ineffective in almost all cases. In addition, HIV infection may be responsible for flare-ups of pre-existing psoriasis, and recalcitrant psoriasis in patients with no history of the disease can also be the initial clinical presentation of the HIV infection [68].

Since HIV-positive patients are excluded from clinical trials, the totality of data on the proper therapeutic management of psoriasis in HIV patients comes from real-life studies. With regard to conventional systemic therapies, MTX and CsA have an important immunosuppressive effect, and consequently their use in this patient setting should not be considered in view of the immunodepressed state caused by HIV infection. As already seen for LTBI and viral hepatitis, apremilast also represents an effective and safe therapeutic option in HIV+ patients, as evidenced in several case reports in the literature, despite having considerably lower efficacy than biological drugs. [69,70,71]. Most of the cases in the literature concern HIV patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors [72]. Myers et al. analysed 39 HIV+ patients suffering from psoriasis and treated with anti-TNF-α, showing therapeutic success in the majority of cases, without the occurrence of serious AEs. Only six patients experienced serious AEs or opportunistic infections [72]. Real-life data for ustekinumab also seem to demonstrate good efficacy and excellent safety in the treatment of psoriasis in HIV+ patients [72]. Indeed, therapeutic success was achieved in the majority of patients, and in some studies it was shown that the CD4+ count not only remained stable but even improved [73]. Furthermore, there are case reports of HIV+ patients successfully treated with ustekinumab after loss of efficacy of adalimumab or etanercept.

Interleukin 17 and IL-23 inhibitors have shown promising results and a good safety profile in the treatment of psoriasis in patients with chronic infections, such as viral hepatitis and LTBI [40, 51, 59]. Likewise, data in the literature seem to confirm the same results in terms of efficacy and safety in HIV+ patients. The American Academy of Dermatology and National Psoriasis Foundation (AAD-NPF) guidelines recommend the use of anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibodies in HIV patients who have been receiving antiretroviral therapy and have a well-controlled viral load [44]. Specifically, with regard to IL-17 inhibitors, there are several case reports in the literature showing that these are an effective and safe therapeutic option for the treatment of psoriasis in HIV+ patients [74, 75]. Similarly, data on the use of IL-23 inhibitors in HIV+ patients are reassuring. Orsini et al. reported four cases of HIV-infected patients treated with risankizumab; in all four cases, therapeutic success was achieved, with no evidence of viral reactivation and no serious AEs, with two out of four patients being treated with risankizumab over a 2-year follow-up period [76]. Finally, regardless of the therapy practised, periodic laboratory monitoring of the CD4+ count and multidisciplinary collaboration with an HIV specialist infectiologist is of crucial importance given the complex management of these patients [77].

COVID-19

COVID-19 is a highly contagious respiratory tract infection caused by the novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2). The first confirmed cases occurred in China in December 2019, and since then over 760 million cases and 6.9 million deaths have been recorded, with these numbers constantly increasing [78]. The COVID-19 pandemic, officially declared on 11 March 2020, had a devastating impact on health, society, and the economy worldwide [79]. Fortunately, the massive worldwide vaccination campaign was a success and minimized the impact of the pandemic on human life [80]. Dermatological clinical practice has also been profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, not only because the infection is often accompanied by skin manifestations [81], but also because SARS-CoV2 infection can induce flare-ups of chronic inflammatory skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [82]. The most important issue, however, was to establish the correct therapeutic management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic, since, at least theoretically, both conventional systemic therapy and biological drugs, by interacting with the immune system, may lead to an increased risk of SARS-CoV2 infection as well as a more severe course of COVID-19. Psoriasis is also often accompanied by comorbidities such as obesity and increased cardiovascular risk, which are clear risk factors for severe COVID-19 [83].

Today, after 4 years of real-life experience in the management of moderate-to-severe psoriasis during the COVID-19 pandemic, we can conclude that patients treated with biological therapy have infection rates comparable to those of the general population and a low rate of hospitalization for COVID-19 [84,85,86]. In particular, the use of TNF-α inhibitors as monotherapy for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMIDs) showed a lower rate of hospitalization and/or death due to COVID-19 than other commonly used therapies such as azathioprine, MTX, and JAK-inhibitors [87]. These findings could be explained by the fact that in patients with severe COVID-19, a cytokine storm is present, characterized among other things by elevated TNF-α levels, which seem to correlate directly with organ damage and a worse disease outcome [88]. These hypotheses are confirmed by several cases of patients with COVID-19 and treated with TNF-α inhibitors with favourable outcomes [89]. Similarly, as shown in the study conducted by Kridin et al., IL-17 inhibitors also did not increase the risk of SARS-CoV2 infection or COVID-19 complications (hospitalization and death) in psoriatic patients, either in comparison with psoriasis patients treated with MTX or relative to those treated with non-systemic/non-immunomodulating therapies [90]. Similar evidence is available for IL-23 inhibitors; in fact, as highlighted by Hu et al., these drugs appear to reduce the risk of COVID-19 and long COVID in patients treated for psoriasis [91].

In addition, numerous studies have shown that biological drugs such as adalimumab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, and guselkumab can reduce the risk of SARS-CoV2 infection as well as prevent the evolution to severe COVID-19 [92,93,94]. Apremilast has also shown a significant protective effect against SARS-CoV2 infection, and therefore this OSM can be considered a safe therapeutic alternative in COVID-19 patients due to its unique and selective mechanism of action [95, 96]. In conclusion, it is clear from the multitude of data in the literature that biological drugs for the treatment of psoriasis do not lead to an increased risk of SARS-CoV2 infection or a worse outcome for COVID-19. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite initial uncertainties and fears, adherence rates to psoriasis therapy were higher among patients treated with biological drugs than among those treated with conventional therapies or topical agents [97, 98]. Therefore, in patients with COVID-19, it is possible to continue current biological therapy by evaluating the individual case in accordance with good clinical practice guidelines. Finally, it was shown that biological treatment did not alter the immune response to the COVID-19 vaccine [99].

Discussion

The risk of severe infection should be ruled out before and during systemic treatment for psoriasis [100]. In this context, we performed a review of the current literature to evaluate the impact of TB, hepatitis B and C, HIV, and COVID-19 infection on psoriasis treatment. As regards TB, LTBI screening is not necessary before starting acitretin, CsA, and fumarates. However, cases of LTBI reactivation during treatment with CsA have been reported. Conversely, LTBI should be ruled out before starting MTX. As regards biological drugs and OSM, LTBI should be ruled out before starting treatment, except for apremilast. However, it should be emphasized that the latest approved classes of biologics (anti-IL-17 and anti-IL-23) do not seem to carry an increased risk of TB reactivation, found in patients treated with anti-TNF-α and ustekinumab.

Similarly, hepatitis B and C should be screened before initiating treatment with conventional (MTX, CsA), OSM (excluded apremilast) and biological therapies for psoriasis. It should be emphasized that in the case of inactive HBV carriers, patients receiving high-to-moderate-risk immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. TNF-α inhibitors, ustekinumab, CsA), prophylactic antiviral treatment is required, whereas inactive HBV carriers who are prescribed low-risk immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. MTX, acitretin, apremilast, IL-17 inhibitors, IL-23 inhibitors) need to be monitored for viral reactivation by determining ALT and HBV DNA levels every 3 months. Nevertheless, consultation with a hepatologist and/or infectiologist, also considering the patient's risk factors, is mandatory.

The treatment of psoriasis in HIV-infected patients is challenging, given the profound state of immunosuppression that the infection causes. On one hand, psoriasis in HIV+ patients is often severe and resistant to first-line therapy; on the other hand, HIV infection may be responsible for flare-ups of pre-existing psoriasis, and recalcitrant psoriasis in patients with no history of the disease can be the initial clinical presentation of the HIV infection. As far as conventional systemic therapies are concerned, MTX and CsA have an important immunosuppressive effect, and consequently their use in this patient setting should not be considered. Also in this case, apremilast is an effective therapeutic option. As regards biologics, data are scant. However, data on the use of use of IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors in HIV+ patients are reassuring. Certainly, a multidisciplinary collaboration with an HIV specialist infectiologist is of crucial importance given the complex management of these patients.

Finally, despite initial doubts on systemic treatment for psoriasis at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, apremilast and biologics were shown to be safe, regardless of the mechanism of action.

It should be emphasized that bimekizumab, the most recently approved monoclonal antibody targeting IL-17A and IL-17F [101], has not been discussed in our manuscript. Despite increasing real-life data showing its effectiveness and safety [102,103,104], there are no data about the use of this drug in patients with serious infectious disease. However, drug insert package reported that careful consideration is necessary when contemplating the utilization of bimekizumab in individuals with a chronic infection or a background of recurrent infection [105]. Moreover, treatment with bimekizumab should be avoided in patients with any clinically significant active infection until the infection has subsided or has been appropriately addressed [105].

To sum up, the management of psoriasis patients with severe infections may be challenging. Excluding the risk of these severe infections, as well as learning to manage them to ensure patients’ access to the right systemic drug, is crucial for offering patients a tailored approach. Certainly, other specialists such as infectiologists and hepatologists should be considered to manage patients with severe infections.

Data Availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–94.

Langley RG, Krueger GG, Griffiths CE. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(Suppl 2):ii18–25.

Potestio L, Camela E, Cacciapuoti S, et al. Biologics for the management of erythrodermic psoriasis: an updated review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:2045–59.

Petit RG, Cano A, Ortiz A, et al. Psoriasis: from pathogenesis to pharmacological and nano-technological-based therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4983.

Yamazaki F. Psoriasis: comorbidities. J Dermatol. 2021;48(6):732–40.

Megna M, Ocampo-Garza SS, Potestio L, et al. New-onset psoriatic arthritis under biologics in psoriasis patients: an increasing challenge? Biomedicines. 2021;9(10):1482.

Kamata M, Tada Y. Efficacy and safety of biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis and their impact on comorbidities: a literature review. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1690.

Camela E, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Megna M. Paradoxical reactions to biologicals for psoriasis. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(12):1435–7.

Megna M, Camela E, Battista T, et al. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecules for psoriasis in pediatric and geriatric populations. Part I: focus on pediatric patients. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(1):25–41.

Megna M, Camela E, Battista T, et al. Efficacy and safety of biologics and small molecules for psoriasis in pediatric and geriatric populations. Part II: focus on elderly patients. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(1):43–58.

Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: Implications for management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(3):393–403.

Rusiñol L, Camiña-Conforto G, Puig L. Biologic treatment of psoriasis in oncologic patients. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(12):1567–78.

Ibrahim S, Amer A, Nofal H, Abdellatif A. Practical compendium for psoriasis management. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(2): e13243.

Carrascosa JM, Del-Alcazar E. Apremilast for psoriasis treatment. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2020;155(4):421–33.

Vu A, Maloney V, Gordon KB. Deucravacitinib in moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Immunotherapy. 2022;14(16):1279–90.

MacNeil A, Glaziou P, Sismanidis C, Maloney S, Floyd K. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis and progress toward achieving global targets—2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(11):263–6.

Ai J-W, Ruan Q-L, Liu Q-H, Zhang W-H. Updates on the risk factors for latent tuberculosis reactivation and their managements. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5(2): e10.

European Medicines Agency. Acitretin 25mg Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). In.

European Medicines Agency. Neoral Soft Gelatin Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). In.

European Medicines Agency. Skilarence 30 mg Gastro-resistant Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). In.

Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43–53.

Fox RJ, Kita M, Cohan SL, et al. BG-12 (dimethyl fumarate): a review of mechanism of action, efficacy, and safety. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:251–62.

European Medicines Agency. Methotrexate 2.5mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). In.

Cantini F, Niccoli L, Capone A, Petrone L, Goletti D. Risk of tuberculosis reactivation associated with traditional disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs and non-anti-tumor necrosis factor biologics in patients with rheumatic disorders and suggestion for clinical practice. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18:415–25.

Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for ≥ 156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

European Medicines Agency. Sotykty 6mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc). In.

Zhang Z, Fan W, Yang G, et al. Risk of tuberculosis in patients treated with TNF-α antagonists: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3): e012567.

Cantini F, Nannini C, Niccoli L, et al. Guidance for the management of patients with latent tuberculosis infection requiring biologic therapy in rheumatology and dermatology clinical practice. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(6):503–9.

Maini R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group Lancet. 1999;354:1932–9.

Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, et al. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098–104.

Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET Consensus Statement. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:1185–206.

Bekker LG, Freeman S, Murray PJ, et al. TNFα controls intracellular mycobacterial growth by both inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent and inducible nitric oxide synthase-independent pathways. J Immunol. 2001;166:6728–34.

Kindler V, Sappino AP, Grau GE, et al. The inducing role of tumor necrosis factor in the development of bactericidal granulomas during BCG infection. Cell. 1989;56:731–40.

Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, et al. Long-term safety of Ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:844–54.

Winthrop KL, Mariette X, Silva JT, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) Consensus Document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (Soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(Suppl 2):S21-s40.

Crowley JJ, Warren RB, Cather JC. Safety of selective IL-23p19 inhibitors for the treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1676–84.

Huang Y-W, Tsai T-F. A drug safety evaluation of risankizumab for psoriasis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(4):395–402.

Megna M, Patruno C, Bongiorno MR, et al. Lack of reactivation of tuberculosis in patients with psoriasis treated with secukinumab in a real-world setting of latent tuberculosis infection. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(5):2629–33.

Manzanares N, Vilarrasa E, López A, et al. No tuberculosis reactivations in psoriasis patients initiating new generation biologics despite untreated latent tuberculosis infection: multicenter case series of 35 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(1):e26–8.

Torres T, Chiricozzi A, Puig L, et al. Treatment of psoriasis patients with latent tuberculosis using IL-17 and IL-23 inhibitors: a retrospective, multinational, multicentre study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25(2):333–42.

Smith CH, Yiu ZZN, Bale T, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2020: a rapid update. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):628–37.

Nast A, Smith C, Spuls PI, et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of Psoriasis vulgaris—part 2: specific clinical and comorbid situations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(2):281–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.16926.

Cui F, Blach S, Manzengo Mingiedi C, et al. Global reporting of progress towards elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):332–42.

Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029–72.

Piaserico S, Messina F, Russo FP. Managing psoriasis in patients with HBV or HCV infection: practical considerations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(6):829–45.

Gisondi P, Altomare G, Ayala F, Bardazzi F, Bianchi L, Chiricozzi A, et al. Italian guidelines on the systemic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:774–90.

Piaserico S, Messina F, Russo FP. Managing psoriasis in patients with HBV or HCV infection: practical considerations. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20:829–45.

Chiu HY, Chiu YM, Chang Liao NF, Chi CC, Tsai TF, Hsieh CY, et al. Predictors of hepatitis B and C virus reactivation in patients with psoriasis treated with biologic agents: a 9-year multicenter cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:337–44.

Amatore F, Villani A-P, Tauber M, et al. French guidelines on the use of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:464–83.

Nast A, Amelunxen L, Augustin M, et al. S3 guideline for the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, update: short version part 2. Special patient populations and treatment situations. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:806–13.

Warren RB, Weatherhead SC, Smith CH, et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the safe and effective prescribing of methotrexate for skin disease 2016. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:23–44.

Tang KT, Chen YM, Chang SN, Lin CH, Chen DY. Psoriatic patients with chronic viral hepatitis do not have an increased risk of liver cirrhosis despite long-term methotrexate use: real-world data from a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:652–8.

European Medicines Agency (EMA). Otezla product information. http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2018/20180802142022/anx_142022_en.pdf.

Abramson A, Menter A, Perrillo R. Psoriasis, hepatitis B, and the tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitory agents: a review and recommendations for management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:1349–61.

Cannizzaro MV, Franceschini C, Esposito M, Bianchi L, Giunta A. Hepatitis B reactivation in psoriasis patients treated with anti-TNF agents: prevention and management. Psoriasis. 2017;7:35–40.

Calabrese LH, Zein NN, Vassilopoulos D. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation with immunosuppressive therapy in rheumatic diseases: assessment and preventive strategies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:983–9.

Koskinas J, Tampaki M, Doumba PP, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during therapy with ustekinumab for psoriasis in a hepatitis B surface-antigen-negative anti-HBs-positive patient. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:679–80.

Bonifati C, Lora V, Graceffa D, Nosotti L. Management of psoriasis patients with hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6444–55.

Bevans SL, Mayo TT, Elewski BE. Safety of secukinumab in hepatitis B virus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:e120–1.

Huang YH, Yen JS, Li SH, Chiu HY. Safety profile of guselkumab in treatment of patients with psoriasis and coexisting hepatitis B or C: a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024:S0190-9622(24)00156-7.

Chiu HY, Hui RC, Huang YH, Huang RY, Chen KL, Tsai YC, Lai PJ, Wang TS, Tsai TF. Safety profile of secukinumab in treatment of patients with psoriasis and concurrent hepatitis B or C: a multicentric prospective cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:829–34.

Megna M, Patruno C, Bongiorno MR, et al. Hepatitis virus reactivation in patients with psoriasis treated with secukinumab in a real-world setting of hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection. Clin Drug Investig. 2022;42(6):525–31.

Ciolfi C, Balestri R, Bardazzi F, et al. Safety profile of risankizumab in the treatment of psoriasis patients with concomitant hepatitis B or C infection: a multicentric retrospective cohort study of 49 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(10):e1203–7.

Potestio L, Piscitelli I, Fabbrocini G, Martora F, Ruggiero A, Megna M. Efficacy and safety of tildrakizumab in a patient with chronic HBV infection. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:369–73.

Weiss RA. How does HIV cause AIDS? Science. 1993;260(5112):1273–9.

HIV and AIDS. (2023, July 13). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids?gad_source=1&gclid=Cj0KCQiA5-uuBhDzARIsAAa21T9VVjMabayRVFugyzRW9PhVEYKecgAl0rw9Wl0RrKYAryBc7ZyIq_MaAu99EALw_wcB

Mallon E, Bunker CB. HIV-associated psoriasis. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2000;14(5):239–46.

Nakamura M, Abrouk M, Farahnik B, Zhu TH, Bhutani T. Psoriasis treatment in HIV-positive patients: a systematic review of systemic immunosuppressive therapies. Cutis. 2018;101(1):38;42;56.

Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64(3):242–4.

Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193.

Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, Bianchi L, Giunta A. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131(3):239–40.

Myers B, Thibodeaux Q, Reddy V, et al. Biologic treatment of 4 HIV-positive patients: a case series and literature review. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2021;6(1):19–26.

Saeki H, Ito T, Hayashi M, et al. Successful treatment of ustekinumab in a severe psoriasis patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1653–5.

Pangilinan MCG, Sermswan P, Asawanonda P. Use of Anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibodies in HIV patients with erythrodermic psoriasis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12(2):132–7.

Qian F, Yan Y, Huang J, et al. Use of ixekizumab in an HIV-positive patient with psoriatic arthritis. Int J STD AIDS. 2022;33(5):519–21.

Orsini D, Maramao FS, Gargiulo L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of risankizumab in HIV patients with psoriasis: a case series. Int J STD AIDS. 2024;35(1):67–70.

Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. CME Part II Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43–53.

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2023 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19).

Lytras T, Tsiodras S. Lockdowns and the COVID-19 pandemic: What is the endgame? Scand J Public Health. 2021;49:37–40.

Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald C-J, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:202–21.

Martora F, Villani A, Battista T, Fabbrocini G, Potestio L. COVID-19 vaccination and inflammatory skin diseases. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(1):32–3.

Shah H, Busquets AC. Psoriasis flares in patients with COVID-19 infection or vaccination: a case series. Cureus. 2022;14(6): e25987.

Birlutiu V, Neamtu B, Birlutiu RM. Identification of factors associated with mortality in the elderly population with SARS-CoV-2 infection: results from a longitudinal observational study from Romania. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17(2):202.

Talamonti M, Galluzzo M, Chiricozzi A, PSO-BIO-COVID study group, et al. Characteristic of chronic plaque psoriasis patients treated with biologics in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: risk analysis from the PSO-BIO-COVID observational study. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21(2):271–7.

Baniandrés-Rodríguez O, Vilar-Alejo J, Rivera R, BIOBADADERM Study Group, et al. Incidence of severe COVID-19 outcomes in psoriatic patients treated with systemic therapies during the pandemic: a biobadaderm cohort analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):513–7.

Gelfand JM, Armstrong AW, Bell S, et al. National psoriasis foundation COVID-19 task force guidance for management of psoriatic disease during the pandemic: version 2—advances in psoriatic disease management, COVID-19 vaccines, and COVID-19 treatments. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(5):1254–68.

Izadi Z, Brenner EJ, Mahil SK, Psoriasis Patient Registry for Outcomes, Therapy and Epidemiology of COVID-19 Infection (PsoProtect); the Secure Epidemiology of Coronavirus Under Research Exclusion for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (SECURE-IBD); and the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Allianc, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and the risk of hospitalization or death among patients with Immune-Mediated inflammatory disease and COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2129639-17.

Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang HH, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020;26(10):1636–43.

Stallmach A, Kortgen A, Gonnert F, Coldewey SM, Reuken P, Bauer M. Infliximab against severe COVID-19–induced cytokine storm syndrome with organ failure—a cautionary case series. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):444. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03158-0.

Kridin K, Schonmann Y, Solomon A, et al. Risk of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality in patients with psoriasis treated by interleukin-17 inhibitors. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(4):2014–20.

Hu Y, Huang D, Jiang Y, Yu Q, Lu J, Ding Y, Shi Y. Decreased risk of COVID-19 and long COVID in patients with psoriasis receiving IL-23 inhibitor: a cross-sectional cohort study from China. Heliyon. 2024;10(2): e24096.

Benhadou F, Del Marmol V. Improvement of SARS-CoV-2 symptoms following Guselkumab injection in a psoriatic patient. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(8):e363–4.

Wu JJ, Liu J, Thatiparthi A, Martin A, Egeberg A. The risk of COVID-19 in patients with psoriasis: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87(6):1395–8.

Conti A, Lasagni C, Bigi L, Pellacani G. Evolution of COVID-19 infection in four psoriatic patients treated with biological drugs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(8):e360–1.

Queiro Silva R, Armesto S, González Vela C, Naharro Fernández C, González-Gay MA. COVID-19 patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis on biologic immunosuppressant therapy vs apremilast in North Spain. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6): e13961.

Armesto S, González Vela C, González López MA. Opportunistic virus infections in psoriasis patients: the safer alternative of apremilast in the COVID-19 era. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(4): e13618.

Kartal SP, Çelik G, Yılmaz O, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on psoriasis patients, and their immunosuppressive treatment: a cross-sectional multicenter study from Turkey. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(4):2137–44.

Tilotta G, Pistone G, Caruso P, et al. Adherence to biological therapy in dermatological patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Western Sicily. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(2):248–9.

Megna M, Potestio L, Battista T, et al. Immune response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in patients with psoriasis undergoing treatment with biologics. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47(12):2310–2.

Camela E, Potestio L, Fabbrocini G, Pallotta S, Megna M. The holistic approach to psoriasis patients with comorbidities: the role of investigational drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2023;32(6):537–52.

Ruggiero A, Potestio L, Martora F, Villani A, Comune R, Megna M. Bimekizumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a drug safety evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2023;22(5):355–62.

Gargiulo L, Narcisi A, Ibba L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of bimekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: a real-life multicenter study-IL PSO (Italian landscape psoriasis). Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1243843.

Megna M, Battista T, Potestio L, et al. A case of erythrodermic psoriasis rapidly and successfully treated with Bimekizumab. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2023;22(3):1146–8.

Orsini D, Malagoli P, Balato A, et al. Bimekizumab for the treatment of plaque psoriasis with involvement of genitalia: a 16-week multicenter real-world experience - IL PSO (Italian Landscape Psoriasis). Dermatol Pract Concept. https://doi.org/10.5826/dpc.1402a52

European Medicines Agency. Bimekizumab – Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/bimzelx-epar-product-information_en.pdf. Last accessed on April 4, 2024.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Matteo Megna: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Giuseppe Lauletta: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Nello Tommasino: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Antonia Salsano: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Teresa Battista: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Angelo Ruggiero: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Fabrizio Martora: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing. Luca Potestio: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Matteo Megna, Giuseppe Lauletta, Nello Tommasino, Antonia Salsano, Teresa Battista, Angelo Ruggiero, Fabrizio Martora, and Luca Potestio is an Editorial Board member of Dermatology and Therapy. Luca Potestio was not involved in the selection of peer reviewers for the manuscript nor any of the subsequent editorial decisions.

Ethical Approval

Not required. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Megna, M., Lauletta, G., Tommasino, N. et al. Management of Psoriasis Patients with Serious Infectious Diseases. Adv Ther 41, 2099–2111 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02873-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02873-2