Abstract

Introduction

In the USA, there is a steady rise of atrial fibrillation due to the aging population with increased morbidity. This study evaluated the risk of stroke/systemic embolism (S/SE) and major bleeding (MB) among elderly patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) and multimorbidity prescribed direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Methods

Using the CMS Medicare database, a retrospective observational study of adult patients with NVAF and multimorbidity who initiated apixaban, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban from January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2017 was conducted. High multimorbidity was classified as having ≥ 6 comorbidities. Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate the hazard ratios of S/SE and MB among three 1:1 propensity score matched DOAC cohorts. All-cause healthcare costs were estimated using generalized linear models.

Results

Overall 36% of the NVAF study population had high multimorbidity, forming three propensity score matched (PSM) cohorts: 12,511 apixaban-dabigatran, 60,287 apixaban-rivaroxaban, and 12,567 dabigatran-rivaroxaban patients. Apixaban was associated with a lower risk of stroke/SE and MB when compared with dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Dabigatran had a lower risk of stroke/SE and a similar risk of MB when compared with rivaroxaban. Compared to rivaroxaban, apixaban patients incurred lower all-cause healthcare costs, and dabigatran patients incurred similar all-cause healthcare costs. Compared to dabigatran, apixaban patients incurred similar all-cause healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Patients with NVAF and ≥ 6 comorbid conditions had significantly different risks for stroke/SE and MB when comparing DOACs to DOACs, and different healthcare expenses. This study's results may be useful for evaluating the risk–benefit ratio of DOAC use in patients with NVAF and multimorbidity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

This study addresses a knowledge gap in healthcare cost and effectiveness of oral anticoagulant therapy among an aging population with multiple morbidities and non-valvular atrial fibrillation. |

Global estimates of those who have atrial fibrillation is a population of approximately 33 million which is expected to double by 2050. |

Because of this growing population, there is an interest in safe and effective treatments for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and multiple morbidities. |

What was learned from the study? |

Among direct oral anticoagulants, there were significant differences in risk and associated costs for stroke/systemic embolism and major bleeding. |

This study highlights the various risks and costs of direct oral anticoagulant treatment in a non-valvular atrial fibrillation with multimorbidity. |

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia in the USA [1]. Globally, 33 million people are estimated to have AF, and that number is expected to double by the year 2050 [2]. In the USA, between 2.7 and 6.1 million individuals are estimated to have AF, and current projections expect that number to rise to between 8 and 12 million by the year 2050 [3]. While patients with non-valvular AF (NVAF) have historically been treated with warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), including apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, and rivaroxaban, are now recommended in the treatment guidelines as a non-inferior, safe, and effective treatment alternative for NVAF [4, 5].

Since NVAF frequently coexists with other chronic comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, heart failure, and ischemic heart disease), patients with AF are frequently categorized as having multimorbidity, defined as the coexistence of two or more comorbid conditions [6]. Given the current aging population, there is a growing concern regarding increasing patients with multimorbidity with a reported median number of six comorbid conditions in these patients [1]. An estimated two-thirds of Medicare patients are characterized as living with multimorbidity, and one-third of them having four or more chronic comorbidities and over 50% having six or more chronic comorbidities [7]. Multimorbidity in patients with AF has previously been associated with increased stroke risk (relative to patients without multimorbidity), worse outcomes after stroke, and lower survival [1, 8]. Despite the need for anticoagulants for NVAF therapy, they are often underused in the multimorbid population. It has been estimated that fewer than half of older adults with AF and multimorbidity (without contraindications) are prescribed anticoagulants [1].

While there have been studies comparing DOACs in AF populations, there is a lack of studies evaluating the effectiveness of DOACs and healthcare costs in older populations with multimorbidity (six or more comorbid conditions) [6, 9, 10]. To address this gap in literature, this study aimed to compare the risk of stroke/systemic embolism (SE) and major bleeding (MB) in patients with NVAF and multimorbidity (six or more comorbid conditions) who initiated a DOAC and the differences in healthcare costs, including all-cause and outcome-related healthcare costs.

Methods

Data Sources and Patient Selection

In this retrospective, observational analysis, patients with NVAF and multimorbidity who newly initiated OAC treatments were selected from Medicare fee-for-service data from the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for the study period of January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2017.

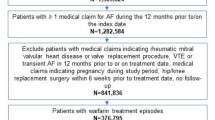

Patients were included in this analysis if they had at least one pharmacy claim for apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or edoxaban during the identification period of January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2017. The first DOAC pharmacy claim during the identification period was designated as the index date [11]. At least one AF diagnosis claim prior to or on the index date was required for all patients, along with continuous medical and pharmacy health plan enrollment for at least 12 months prior to the index date (baseline period). Patients also needed to be at least 65 years of age. Patients prescribed edoxaban were eventually excluded from the final study population because of insufficient sample size. Detailed exclusion criteria are listed in Fig. 1. There was no patient overlap between cohorts as this was an on-treatment analysis, and patients were censored when a switch occurred from their index drug.

Multimorbidity was defined as having concurrent chronic health conditions (Table 1) at baseline, which represent common conditions among patients with AF and conditions that could be related to the outcomes of interest [12]. Only patients with high multimorbidity (six or more concurrent chronic health conditions) were included in this analysis to be consistent with the highest risk group in the literature [1, 7, 8].

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes of interest were time to first stroke/SE and time to first MB among patients with high multimorbidity. Stroke/SE and MB were identified using hospital claims that included the outcome as the primary listed ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code. Stroke/SE was identified as having at least one stroke/SE event during the follow-up period and was stratified into three categories: ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and SE. MB was identified as having at least one MB event during the follow-up period and was also stratified into three categories: gastrointestinal hemorrhage, intracranial hemorrhage, and other major bleeding. The secondary outcomes of interest were follow-up stroke/SE or MB-related medical costs (per patient per month, PPPM) and follow-up all-cause healthcare costs (PPPM) among patients with high multimorbidity. Stroke/SE and MB-related medical costs were defined as the costs from the first stroke/SE- and MB-hospitalization plus all subsequent claims with a stroke/SE and MB diagnosis, respectively. The follow-up period started the day after the index date and continued to the earliest of 30 days after the date of treatment discontinuation, treatment switch, end of continuous medical and pharmacy enrollment, death, or end of the study period.

Statistical Analysis

The study population was initially directly matched on the basis of the level of multimorbidity (low, moderate, high). Subsequently, 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted for each comparison group: DOAC vs. DOAC (apixaban vs. dabigatran, apixaban vs. rivaroxaban, and dabigatran vs. rivaroxaban) [11, 12]. The variables used in PSM included demographics (age, gender, geographic region, race, Medicaid dual eligibility, part D low income subsidy), comorbidities (bleeding history, coagulation defects, alcoholism, all conditions in Table 1), and baseline healthcare utilization (ER visit, inpatient admission). The nearest neighbor method without replacement, and a caliper of 0.01 was used to select matched samples. Furthermore, the balance of covariates between the matched treatment groups was determined using an absolute standardized difference of the mean of 0.10 or less [13].

Cumulative incidence rates were illustrated using Kaplan–Meier curves, and Cox proportional hazard models, with robust sandwich estimates, were used to assess the risk of stroke/SE and MB [14]. Treatment groups were included in the Cox models as independent variables, as matched confounders were balanced after PSM. A p value of 0.05 was used as the cutoff for statistical significance. All-cause, stroke/SE, and MB-related costs were evaluated using generalized linear models with bootstrapping. Two-part models were used for evaluating stroke/SE and MB-related costs.

Ethics Compliance

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. Since this study did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was deemed exempt from institutional review board review by Solutions IRB. Both the data sets and the security of the offices where analysis was completed (and where the data sets are kept) meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

Results

After applying the selection criteria, 22.1% (n = 163,073) of the NVAF population newly initiated on OACs (n = 737,214) had multimorbidity; 87,436 (53.6%) initiated apixaban, 12,587 (7.7%) dabigatran, and 63,050 (38.7%) rivaroxaban, (Fig. 1). Before PSM, ages ranged from 78.1 to 79.6 years, with apixaban patients being the oldest. CCI, CHA2DS2-VASc, and HAS-BLED scores ranged from 5.0 to 5.5, 5.7 to 5.8, and 4.1 to 4.2, respectively, with apixaban patients having higher CCI, CHA2DS2-VASc, and HAS-BLED scores compared to dabigatran and rivaroxaban patients (Supplementary Table 1).

The unadjusted incidence rates of stroke/SE per 100 person-years were 1.7 (apixaban), 2.0 (dabigatran), and 1.8 (rivaroxaban). The unadjusted rates for MB per 100 person-years were 6.2 (apixaban), 7.0 (dabigatran), and 9.2 (rivaroxaban).

After PSM, patient pairs were evaluated, including: 12,511 patient apixaban-dabigatran, 60,287 apixaban-rivaroxaban, and 12,567 dabigatran-rivaroxaban pairs (Fig. 1). The mean number of comorbidities ranged from 7.6 to 7.7 across the drug cohorts. Coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were among some of the most prevalent comorbid conditions (Table 2). Initial baseline characteristics of the matched populations and detailed information on comorbidities and concomitant medications are shown in Table 2. Baseline healthcare utilization and cost are in Table 3.

DOAC vs. DOAC Comparisons

Compared to rivaroxaban, apixaban was associated with a lower risk of stroke/SE (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81–1.00), while dabigatran was associated with a similar risk of stroke/SE (HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.84–1.28). Compared to dabigatran, apixaban was associated with a lower risk of stroke/SE (HR 0.71, 95% CI 0.57–0.89). Compared to rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran were associated with lower risks of MB (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.59–0.65; HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.71–0.87, respectively), and apixaban was associated with a lower risk of MB (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.72–0.90) when compared with dabigatran (Fig. 2).

Healthcare Costs

Compared to rivaroxaban, apixaban was associated with lower all-cause hospitalization costs PPPM ($2371 vs. $2652, p < 0.001) and all-cause medical costs PPPM ($3589 vs. $3806, p < 0.001) and dabigatran was associated with similar costs (inpatient: $2448 vs. $2564, p = 0.330; total medical: $3541 vs. $3729, p = 0.107). All-cause hospitalization costs PPPM and all-cause medical costs PPPM were similar among apixaban when compared to dabigatran (inpatient: $2344 vs. $2450, p = 0.265; total medical costs: $3509 vs. $3542, p = 0.711). Compared to rivaroxaban, apixaban and dabigatran had lower MB-related medical costs PPPM (apixaban: $209 vs. $309, p < 0.001; dabigatran: $240 vs. $294, p = 0.045). MB-related medical costs PPPM were similar for apixaban and dabigatran patients ($192 vs. $241, p = 0.141). Stroke/SE-related medical costs PPPM were similar among apixaban ($70 vs. $69, p = 0.940) and dabigatran ($64 vs. $74, p = 0.469) when compared with rivaroxaban, and apixaban when compared with dabigatran ($55 vs. $64, p = 0.562) (Table 4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of Medicare patients with NVAF analyzed to evaluate the effectiveness, safety, and healthcare costs of DOAC treatment among patients with at least six comorbid conditions. In our analysis, DOACs were associated with differing risks of stroke/SE and MB in addition to varying healthcare costs.

Since multimorbidity is frequently associated with other comorbidities, multimorbidity is common in patients with NVAF [15]. The number of patients with NVAF in the context of multimorbidity is only expected to increase in the future. Multimorbidity has previously been associated with an increased risk of stroke, bleeding, poor recovery after a stroke, and death [15]. Our current results are consistent and reinforce our previous analysis of administrative claims databases [9]. In that study, we also included patients from four commercial claims databases, along with Medicare patients. While that study found varying risks of stroke/SE and MB among patients, they found dabigatran to be associated with a higher risk of stroke/SE compared to rivaroxaban, while we found similar risk. These differences may have been due to our Medicare population consisting of older patients and the longer follow-up in this study. A prior ARISTOTLE post hoc analysis also found that multimorbid apixaban patients trended toward a lower risk of stroke/SE and MB compared to warfarin, which is consistent with the main trial results [6]. In that study, patients were classified by the number of comorbidities into the following groups: as no multimorbidity (0–2 comorbidities), moderate multimorbidity (3–5 comorbidities), and high multimorbidity (at least 6 comorbidities). The risks of stroke/SE and MB were elevated for patients in the high and moderate multimorbidity groups compared with the no multimorbidity group.

Few other studies have evaluated the effectiveness of OAC treatment for patients with NVAF in the context of multimorbidity. A previous study evaluated a cohort of newly diagnosed AF Medicare patients initiating 150 mg dabigatran, 20 mg rivaroxaban, or warfarin therapy [10]. Instead of using an actual number of comorbidities, CHA2DS2VASc, HAS-BLED, and Gagne comorbidity scores were used as a proxy for multimorbidity. The authors found rivaroxaban to be associated with a higher risk of MB across the three comorbidity scores when compared to dabigatran, which was consistent with our results. Any differences in some of our findings may be due to their use of comorbidity scores to measure multimorbidity as opposed to our use of number of comorbidities.

In addition to the enormous healthcare burden of multimorbid patients, they also carry a significant economic burden [16, 17]. In our study, apixaban use was associated with lower healthcare costs when compared to rivaroxaban but similar costs when compared to dabigatran. Our results are partially consistent with those of a prior Medicare study comparing cost differences between apixaban and other OACs, which found that apixaban patients were associated with lower healthcare costs when compared to dabigatran and rivaroxaban [17]. The differences in our apixaban vs. dabigatran outcomes may be due to our longer study period (2012–2019 vs. 2012–2014) and longer mean follow-up (265.5–283.4 days vs. 144.6–185.2 days). Other work using data from the Department of Defense [18] showed that apixaban had lower cost in patients with NVAF compared to warfarin ($2277 vs. $2498, p = 0.148), dabigatran ($2142 vs. $2372, p = 0.150), and rivaroxaban ($2200 vs. $2546, p < 0.001) after PSM. Though our results are limited to those with multimorbidity they are consistent with this prior work and observed differences are due to differences in the data source used and the inclusion of non-multimorbid patients.

While this study focuses on patients with multimorbidity, previous subgroup analyses for renal insufficiency, cancer, and concomitant use of antiplatelet drugs and NSAIDs among others have been published [19,20,21]. Additionally, a systematic literature review found DOACs to be associated with improved safety and efficacy in patients with AF and liver cirrhosis [22]. Compared to previous studies, this study provides a large data set of NVAF Medicare patients over the age of 65 with multimorbidity. The results of this study are consistent with that of prior real-world evidence studies in that DOACs are associated with varying risk profiles.

Limitations

For this retrospective observational study, only statistical associations could be concluded, not causal relationships. Although cohorts were matched through PSM, there were potential residual confounders. As a result of the nature of claims studies, outcome measures could only be based on ICD-9/10-CM codes without further adjustment with precise clinical criteria. In addition, clinical data, such as creatinine clearance and weight, were not available in this administrative claims data source; therefore, this study was unable to identify appropriate and inappropriate use of low-dose regimens. Also, laboratory values, such as hemoglobin, are not available in the data set.

This study used both the distribution of comorbidities at baseline and previously published ARISTOTLE trial subgroup analyses to define multimorbidity, but the definition of multimorbidity differs from some other studies and presents a challenge to compare our findings with those of other studies. While all patients were required to have at least six comorbidities, the severity of conditions remained unknown and may not be equal among patients. Moreover, unobserved heterogeneity may exist across the five data sources. Finally, the results only reflect the Medicare multimorbid NVAF population and may not represent other multimorbid NVAF populations such as those with commercial insurance.

Conclusion

Patients with NVAF and at least six comorbid conditions have varying risks for stroke/SE and MB when comparing DOACs to DOACs. The observed variation in costs when comparing DOACs to DOACs indicates another factor that could be considered when choosing a treatment for NVAF in the multimorbid population. The results of this study may be helpful for evaluating the risk–benefit ratio of DOAC use in patients with NVAF and multimorbidity.

References

Parks AL, Fang MC. Anticoagulation in older adults with multimorbidity. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):331–46.

Kumar S, de Lusignan S, McGovern A, et al. Ischaemic stroke, haemorrhage, and mortality in older patients with chronic kidney disease newly started on anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a population based study from UK primary care. BMJ. 2018;360:k342.

Chamberlain AM, Alonso A, Gersh BJ, et al. Multimorbidity and the risk of hospitalization and death in atrial fibrillation: a population-based study. Am Heart J. 2017;185:74–84.

Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955–62.

January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/ HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104–32.

Alexander KP, Brouwer MA, Mulder H, et al. Outcomes of apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation and multi-morbidity: insights from the ARISTOTLE trial. Am Heart J. 2019;208:123–31.

Chen MA. Multimorbidity in older adults with atrial fibrillation. Clin Geriatr Med. 2016;32(2):315–29.

Jani BD, Nicholl BI, McQueenie R, et al. Multimorbidity and co-morbidity in atrial fibrillation and effects on survival: findings from UK Biobank cohort. Europace. 2018;20(3):329–36.

Deitelzweig S, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Use of non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and multimorbidity. Adv Ther. 2021;38(6):3166–84.

Mentias A, Shantha G, Chaudhury P, Vaughan Sarrazin MS. Assessment of outcomes of treatment with oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation and multiple chronic conditions: a comparative effectiveness analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182870.

Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):e003725. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003725.

Lopes RD, Alexander JH, Al-Khatib SM, et al. Apixaban for reduction in stroke and other thromboembolic events in atrial fibrillation (ARISTOTLE) trial: design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2010;159(3):331–9.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3697.

Austin PC. The use of propensity score methods with survival or time-to-event outcomes: reporting measures of effect similar to those used in randomized experiments. Stat Med. 2014;33(7):1242–58.

Proietti M, Marzona I, Vannini T, et al. Long-term relationship between atrial fibrillation, multimorbidity and oral anticoagulant drug use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(12):2427–36.

Hajat C, Siegal Y, Adler-Waxman A. Clustering and healthcare costs with multiple chronic conditions in a US study. Front Public Health. 2021;8:607528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.607528.

Amin A, Keshishian A, Trocio J, et al. A real-world observational study of hospitalization and health care costs among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients prescribed oral anticoagulants in the US Medicare population [published correction appears in J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020 May;26(5):682]. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(5):639–651.

Gupta K, Trocio J, Keshishian A, et al. Real-world comparative effectiveness, safety, and health care costs of oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients in the US department of defense population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(11):1116–27. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2018.17488s.

Deitelzweig S, Keshishian AV, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients with active cancer. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(3):411–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccao.2021.06.004.

Shrestha S, Baser O, Kwong WJ. Effect of renal function on dosing of non-vitamin K antagonist direct oral anticoagulants among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(2):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028017728295.

Lip GYH, Keshishian A, Kang A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral anticoagulants among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients with polypharmacy. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2021;7(5):405–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa117.

Lee ZY, Suah BH, Teo YH, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants and vitamin K antagonists in patients with atrial fibrillation and concomitant liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2022;22(2):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-021-00482-w.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was funded by Pfizer, Inc. and Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. The study sponsors are also funding the journal’s Rapid Service and Open Access Fees.

Medical Writing, Editorial and Other Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Christopher Moriarty and Michael Moriarty, employees of STATinMED, LLC which is a paid consultant to the study sponsors. Support for this assistance was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer.

Author Contributions

ADD: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. MF: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. AK: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing, visualization. CR: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing, visualization. NA: methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. CG: formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. BE: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. HY: conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. MDF: conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review & editing, visualization.

Disclosures

This study was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer. Amol Dhamane, Mauricio Ferri, and Nipun Atreja are paid employees and shareholders of Bristol Myers Squib; Huseyin Yuce is an employee of the City University of New York; Manuela Di Fusco, Cristina Russ and Birol Emir are paid employees and shareholders of Pfizer; at the time the study was conducted, Allison Keshishian and Cynthia Gutierrez were paid employees of STATinMED, LLC, which is a paid consultant to Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb in connection with the development of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments. Since this study did not involve the collection, use, or transmittal of individually identifiable data, it was deemed exempt from institutional review board review by Solutions IRB. Both the data sets and the security of the offices where analysis was completed (and where the data sets are kept) meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. Solutions IRB determined this study to be EXEMPT from the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)’s Regulations for the Protection of Human Subjects (45 CFR 46) under Exemption 4: Research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects. The HIPAA Authorization Waiver was granted in accordance with the specifications of 45 CFR 164.512(i). This project was conducted in full accordance with all applicable laws and regulations, and adhered to the project plan that was reviewed by Solutions Institutional Review Board.

Data Availability

The raw insurance claims data used for this study originate from Medicare data, which are available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid through ResDAC (https://www.resdac.org/). Other researchers could access the data through ResDAC, and the inclusion criteria specified in the Methods section would allow them to identify the same cohort of patients we used for these analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dhamane, A.D., Ferri, M., Keshishian, A. et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Among Patients with Non-valvular Atrial Fibrillation and Multimorbidity. Adv Ther 40, 887–902 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02387-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-022-02387-9