Abstract

Aims

Estimate the prevalence of symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder (OAB) in women living in the Middle East to describe their demographic characteristics and explore treatment-seeking behavior.

Methods

Cross-sectional, population-based survey of women aged ≥ 40 years resident in Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon or Egypt. Respondents were recruited using computer-assisted telephone interview over approximately 4 months. Eligible respondents were asked to complete the OAB-V8, a validated questionnaire that explores the extent of bother from the key symptoms of OAB without clinical investigations. In addition, information regarding demographics, comorbidities and treatment behavior was collected, and respondents were stratified by age.

Results

A total of 2297 eligible women agreed to participate. Mean age was 54 ± 10 years; over half (59.3%) were aged 40–55 years. Overall, 53.8% of eligible women had symptoms suggestive of OAB (Jordan 58.5%; Egypt 57.5%; Algeria 49.9%; Lebanon 49.0%), with over 90% also reporting symptoms of urinary incontinence. Only 13.0% of women with symptoms suggestive of OAB were currently receiving treatment, while most (74.3%) had never been treated; these data were consistent across country and age categories. Among the untreated subgroup, almost half (48.7%) reported they were ‘not bothered by symptoms,’ while 8.4% considered OAB to be ‘part of normal aging’ and 4.7% did not know it was treatable.

Conclusion

A high prevalence of symptoms suggestive of OAB was observed, and the majority had symptoms of urinary incontinence. Despite the high prevalence, most women had never received treatment. Considering the potential significant impact of OAB symptoms on health, quality of life and productivity, these findings highlight an unmet medical need in the population studied. Strategies to improve treatment-seeking behavior (e.g., through education and tackling the stigma associated with OAB symptoms) may improve the diagnosis, management and health outcomes of women with OAB in the Middle East.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Overactive bladder (OAB) affects millions of people worldwide; symptoms experienced may have a negative impact on quality of life and may lead to some patients not seeking treatment. |

There are few published data describing the prevalence of OAB symptoms and the associated treatment-seeking behavior of patients with OAB residing in the Middle East. |

What was learned from the study? |

A high prevalence of OAB was observed in the Middle East with approximately 50% of the women aged ≥ 40 years reporting symptoms suggestive of OAB and > 90% of these women reporting symptoms of urinary incontinence. |

Despite the high prevalence of symptoms suggestive of OAB, 74% of women had never been treated and only 13% of women were currently receiving treatment. |

There appears to be an unmet medical need in Middle Eastern women aged ≥ 40 years, and strategies to improve treatment-seeking behavior as well as the diagnosis, management and health outcomes may be required. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13296245.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a common condition characterized by urinary urgency, usually accompanied by increased daytime frequency and/or nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence (UUI; OAB-wet or OAB-dry, respectively), in the absence of urinary tract infection or other detectable disease [1, 2].

Some 546 million individuals worldwide were expected to be affected by OAB in 2018 [3], with the overall prevalence increasing with advancing age and highest rates reported in those aged 65–80 years [4,5,6,7]. OAB appears to affect similar proportions of women and men, although some of the available evidence suggests a slightly higher prevalence in women [3,4,5, 8]. The prevalence estimates for women in large population- or community-based epidemiologic studies range from 1.9% in China [9] to 8.1% in Japan [10] and 24.7% in the USA [5]. There is some evidence of an impact of race and ethnicity on the symptoms of OAB (although data are mainly limited to US populations) [11, 12].

The negative impact of OAB symptoms on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) has been well documented [8, 13]. It is expected that daily living and participation in both social and occupational activities can be profoundly affected by OAB symptoms. A number of studies have therefore focused on the physical and emotional dimensions that have the most impact on HRQoL [14]. OAB has also been associated with anxiety and depression [15] and sleep disturbance [8]. Urinary incontinence, in particular, may have severe psychologic and social consequences, for example, an unwillingness to leave home without a familiarity of access to toilets. In addition, OAB represents a heavy socioeconomic burden, affecting both employment and productivity [12, 16,17,18].

A systematic literature review estimated the total national cost of OAB in the USA to be $65.9 billion in 2007, with an estimated increase to $82.6 billion in 2020 [19]. An analysis of six western countries (Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, Sweden and the UK) estimated that the total direct costs of OAB (excluding nursing home and productivity costs) were in excess of €3.5 billion (2005 costs) [20].

If conservative management strategies are ineffective, pharmacotherapy with oral antimuscarinics or beta-3 adrenoceptor agonists may result in OAB symptom improvement [21, 22]. Yet, despite the high burden from OAB and the availability of effective treatments, the number of patients with OAB seeking medical advice is consistently limited [23,24,25,26]. Few studies have investigated the prevalence of OAB symptoms and the associated treatment-seeking behavior in the Middle East, and none of the available studies have attempted to establish baseline data at a national or regional level [27,28,29,30].

Methods

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional, population-based telephone survey to identify women residing in Algeria, Jordan, Lebanon or Egypt with symptoms suggestive of OAB as measured by the validated OAB-V8 symptom bother questionnaire [31,32,33] over approximately 4 months in 2018.

Patient Recruitment and Eligibility

Women aged ≥ 40 years who were residing in one of the four countries (Algeria, Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon) during the study and who provided verbal informed consent via telephone were included. Women who reported currently being pregnant and/or had symptoms consistent with other obvious urinary conditions (e.g., fever, dysuria and/or hematuria), including urinary tract infections, were excluded.

Data Collection

Data were collected directly from survey participants using the computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) method [34]. Random Digit Dialing computer software was used to assist in determining telephone numbers to dial for each country from a national public telephone directory. This sampling methodology was utilized to maximize the coverage in all areas in each country (including urban, semi-urban and rural areas), taking landline area code into consideration. Based on our assumptions [30% of phone calls would be answered; 50% of households would have an eligible woman available; 15% of women would be aged ≥ 40 years; 30% would agree to consent and participate; and with a 15% prevalence of OAB (with a uniform prevalence across all countries)], it was estimated that a sample size of 550 women per country (total 2200) would achieve a margin of error of ± 3% with a 95% confidence level (CI). Overall, it was estimated that 2.3% of women contacted would be eligible and willing to participate.

Conduct of the Survey

After providing a brief overview of the study, including the objective (conducting a health-related telephone survey) and the expected duration (< 15 min to complete the interview), the eligibility of each respondent was established (Table S1). Following confirmation of verbal consent, respondents were advised that they were free to withdraw from the study at any point during the call without having to provide any reason(s). Respondents were invited to complete the OAB-V8 questionnaire in their preferred language [English (Table S2), French, or Arabic] and were also asked to provide additional information regarding demographics and treatment behavior.

Data Analysis

Data collected from questionnaires were captured immediately on an electronic case report form electronic system to avoid data transfer errors. Data analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.13 HF3. The OAB-V8 was designed to assess the extent of bother from four hallmark symptoms of OAB: urinary frequency, urgency, nocturia and urge incontinence [32]. Patients responded to eight questions using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (a very great deal), with a maximum possible score of 40. The study was not designed to diagnose OAB patients, as it was not clinic based. However, the odds ratio for having OAB vs. not having OAB among those who scored ≥ 8 on the OAB-V8 questionnaire during its validation process was 95.7 (95% CI 29.3–312.4) [31, 32].

In our analysis, respondents who scored ≥ 8 on the OAB-V8 questionnaire plus scores ≥ 1 for questions 2 (bothered by an uncomfortable urge to urinate), 3 (bothered by a sudden urge to urinate with little or no warning) and 7 (bothered by an uncontrollable urge to urinate) were considered to have symptoms suggestive of OAB. Among respondents with symptoms of OAB, those who scored ≥ 1 on questions 4 (bothered by accidental loss of small amounts of urine) and 8 (bothered by urine loss together with a strong desire to urinate) were considered also to have urinary incontinence (OAB-wet).

Descriptive statistics were performed on qualitative data to summarize all outcome variables, including symptom description, basic demographics, comorbidities and treatment behavior. Respondents were stratified according to age (40–55, 56–64, 65–74 and ≥ 75 years), and there was no cap on any group size. Categorical variables were summarized as the number and proportion of the total study population, and by subgroups where appropriate, and continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD). No formal hypothesis testing was performed.

Ethics Approval

The study was conducted with ethical approval and informed consent, and in accordance to Helsinki Declaration. The ethics approval procedure differed in each country. The review boards for each country and reference numbers are as follows: Egypt: Central IRB at Egyptian Ministry of Health (15-2018/19); Jordan: IRB at School of Medicine, University of Jordan (1692/2018/67); Algeria: IRB at EHU Oran Algeria and Central IRB notification to Algerian Ministry of Health (11-07-2018); Lebanon: IRB at Lebanese Hospital Geitaoui University Medical Centre (2018-IRB-010).

Results

Study Population

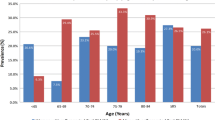

A total of 32,261 households (Algeria, n = 4704; Egypt, n = 5799; Jordan, n = 6475; Lebanon, n = 15,283) were contacted by telephone. From these interactions, a total of 2297 women (Algeria, n = 573 [response rate: 12.2%]; Egypt, n = 600 [10.3%]; Jordan, n = 561 [8.7%]; Lebanon, n = 563 [3.7%]) met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the telephone interview (an overall response rate of 7.1%). Demographics and lifestyle characteristics of the study respondents are shown in Table 1. Overall, the mean (SD) age was 54 (9.8) years, with lowest mean age (49.2 [8.6] years) in Algeria. Most respondents (59.3%) were in the 40–55 year age stratum, with < 3% aged ≥ 75 years (Fig. 1).

The mean (SD) score on the OAB-V8 questionnaire in the overall population was 10.9 (9.2), ranging from 9.7 (8.8) in Lebanon to 12.0 (9.9) in Egypt (Table 2). Overall, the prevalence of women with symptoms suggestive of OAB (i.e., scoring ≥ 8 on the questionnaire overall, plus scoring ≥ 1 for the urgency questions 2, 3, and 7) was 1235 (53.8%), with the highest prevalence in Jordan (328 [58.5%]), followed by Egypt (345 [57.5%]), Algeria (286 [49.9%]) and Lebanon (276 [49.0%]). The overall prevalence of OAB-wet (i.e., scoring ≥ 8 on the questionnaire overall, plus scoring ≥ 1 for questions 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8) was 1128 (49.1%)—91.3% of those with OAB symptoms.

The prevalence of women with symptoms suggestive of OAB did not notably differ by age category (Table 3), with a consistently high prevalence of OAB-wet among women with symptoms suggestive of OAB across age categories (n = 676 [91.1%] for 40–55 years and n = 32 [94.1%] for ≥ 75 years; Table 3). Almost half of the women with symptoms suggestive of OAB reported at least one comorbidity (Table 4), with hypertension (n = 398 [32.2%]) and diabetes (n = 272 [22.0%]) being most commonly reported across all regions.

The treatment-seeking behavior of women with symptoms suggestive of OAB who were actively on therapy, who had been previously treated or had never been treated is summarized by country and age group in Table 5. Overall, only 101 (8.2%) women with symptoms suggestive of OAB had been previously treated, and only 161 (13.0%) women were currently receiving therapy, ranging from 35 (12.7%) among women in Lebanon to 53 (15.4%) among women in Egypt. Most women with symptoms suggestive of OAB had never been treated (n = 918 [74.3%]). Almost half of those who had never been treated (n = 447 [48.7%]) reported they were ‘not bothered by symptoms’ (Table 6). Of note, Algeria and Egypt had the highest proportion of respondents who ‘did not know it was treatable’ (n = 18 [9.9%] and n = 17 [6.5%], respectively) and thought it ‘part of normal aging’ (n = 20 [11.0%] and n = 28 [10.6%], respectively).

In addition, 320 (34.9%) women reported ‘other reasons’ (not specified) for not receiving treatment.

Discussion

The results of this population-based telephone survey suggest there is a high prevalence (53.8%) of OAB symptoms among women aged ≥ 40 years in the Middle Eastern setting, with > 90% of women with symptoms suggestive of OAB also reporting OAB-wet symptoms. OAB prevalence estimates have been shown to vary considerably among studies, ranging from approximately 3–43% [4]. However, it is challenging to directly compare the results of this study with those of other prevalence studies, largely because of differences in methodology, e.g., inclusion of both men and women, differences in the definition of OAB, inclusion of individuals of varying age groups, and differences in treatment practices and patient perception across regions/countries.

Only a few studies have investigated the prevalence of OAB in the Middle East. One community-based study conducted by El-Azab et al. in Egypt (n = 1652 women) reported a prevalence of 40% for OAB symptoms [29], which is lower than the prevalence estimated in this study for Egypt (57.5%). A possible explanation for this difference may be the inclusion of younger women (≥ 20 years) in the El-Azab et al. study [29], and it is well-established that OAB symptoms are more common in individuals of advanced age [4].

In addition to age, other risk factors for OAB symptoms were common in this sample population of women. For example, the mean body mass index was 28.9 kg/m2 (overweight), and most women were post-menopausal (60.8% of respondents). Additionally, approximately half of all women with symptoms suggestive of OAB experienced at least one comorbidity (48.9%), and diabetes was the second most common comorbidity overall (22.0% of respondents). These data are consistent with other studies, which have shown an association between OAB and multiple factors including age, body mass index, marital status, high parity rate, smoking, diabetes, previous hysterectomy and post-menopausal status [26, 35,36,37]. These results suggest that women in the Middle East have a range of risk factors that may increase their likelihood of experiencing OAB symptoms. These findings are in line with those from a global study, which estimated a higher prevalence of OAB in Asia compared with Europe, Africa, and North and South America [3].

Despite the high prevalence of OAB symptoms and > 90% of women having symptoms of OAB-wet, our study revealed that only 13% were currently receiving treatment and 8% were previously treated; 74% of respondents had never received treatment, with the most common specified reason being ‘not bothered by symptoms.’ A previous survey of six European countries reported a treatment rate of approximately 27% and that the most common reason for not seeking help, for both men and women (61% and 56%, respectively), was the belief that no effective treatment was available [4]. In addition, a small study conducted in Egypt (n = 91) showed that only 4% of women with UUI sought medical advice [29].

It has previously been suggested that many individuals with OAB are reluctant to seek medical care, a characteristic that has been attributed to social stigma and/or embarrassment associated with an inability to control the bladder; these individuals often endure the inconvenience and unpleasantness of symptoms [4]. UUI in particular may have a severe impact on HRQoL, self-esteem, relationships and fear/anxiety. The severity of OAB symptoms appears to be associated with the adoption of non-medical coping strategies (e.g., controlling fluid intake and use of pads) rather than consulting a healthcare professional [38, 39].

For individuals with OAB symptoms, the impetus to seek medical treatment may be multifactorial, e.g., the number of and/or bother from OAB symptoms and the age of the patient [5]. It also appears that patients often consider the condition a normal part of aging or that they are unaware that effective treatment is available [4, 40,41,42]. Indeed, there are currently several treatment modalities available, including education and lifestyle modification plus pharmacotherapy with oral antimuscarinic or beta-3 adrenoceptor agonist agents [21, 22].

In 2018, the population in the Middle East region approached 450 million, with approximately 35% resident in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon [43]. Considering the significant impact that OAB symptoms can have on HRQoL, these findings suggest that there is an unmet medical need in a significant number of women in the Middle East region. Strategies to improve treatment-seeking behavior (e.g., through reassurance, education and addressing the stigma associated with urinary symptoms) may therefore improve the management and health outcomes of women in the Middle East with OAB.

Limitations

In this cross-sectional survey, all data collected on symptoms were based on self-report without medical validation. In this disease area, the diagnosis of conditions involving lower urinary tract symptoms, including OAB, is often driven by patient self-report. The under-reporting of urinary symptoms has been observed in published research due to social stigma from inability to control the bladder [40,41,42]. Therefore, participants may not have been comfortable sharing their symptoms with interviewers. However, the CATI method is considered more anonymous than a face-to-face interview; incontinence was assessed by responses to the OAB-V8 questionnaire meaning that women did not have to explicitly describe their symptoms. The methodology used here may have allowed for participants to be more open about their urinary symptoms without the worry of social stigma.

Of all the households contacted, 7.1% were identified as eligible and agreed to participate in the study. As participants were informed that it was a health-related telephone survey prior to consenting it is possible that unwell women were more engaged and likely to agree to participate in this survey (perhaps as an outlet to discuss their symptoms) compared with women who had good health. Additionally, most women who participated were aged 40–55 years (59.3%), and thus the generalizability of the results is somewhat limited to this age category.

Since self-reported information is susceptible to recall bias, there may also have been systematic errors caused by differences in the accuracy of the recollections retrieved by participants (regarding symptom bother during the past 4 weeks). In addition, some symptoms may not have been fully recognized by participants as being suggestive of OAB, a particular concern in developing countries. Furthermore, data for some demographic characteristics, including a history of gynecologic surgeries and deliveries associated with an increased risk of OAB symptoms, were not available in this survey. Finally, barriers to treatment and coping strategies were not explored in this study, nor was the compliance with treatment in those receiving current therapy.

Conclusions

Approximately 50% of women aged ≥ 40 years in the Middle Eastern setting had symptoms suggestive of OAB. The majority of these women described symptoms suggestive of urinary incontinence, and most women had never received treatment. These data suggest an unmet medical need and highlight the requirement for strategies to improve treatment-seeking behavior in this region.

References

D’Ancona C, Haylen B, Oelke M, et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:433–77.

Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:116–26.

Irwin DE, Kopp ZS, Agatep B, Milsom I, Abrams P. Worldwide prevalence estimates of lower urinary tract symptoms, overactive bladder, urinary incontinence and bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2011;108:1132–8.

Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, et al. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–6.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, et al. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology. 2011;77:1081–7.

Funada S, Kawaguchi T, Terada N, et al. Cross-sectional epidemiological analysis of the Nagahama Study for correlates of overactive bladder: genetic and environmental considerations. J Urol. 2018;199:774–8.

Chuang YC, Liu SP, Lee KS, et al. Prevalence of overactive bladder in China, Taiwan and South Korea: results from a cross-sectional, population-based study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2019;11:48–55.

Stewart WF, Van Rooyen JB, Cundiff GW, et al. Prevalence and burden of overactive bladder in the United States. World J Urol. 2003;20:327–36.

Wen JG, Li JS, Wang ZM, et al. The prevalence and risk factors of OAB in middle-aged and old people in China. Neurourol Urodyn. 2014;33:387–91.

Ninomiya S, Naito K, Nakanishi K, Okayama H. Prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder in Japanese Women. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2018;10:308–14.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Bell JA, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and overactive bladder (OAB) by racial/ethnic group and age: results from OAB-POLL. Neurourol Urodyn. 2013;32:230–7.

Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Kopp ZS, Kaplan SA. Racial differences in the prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States from the epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. Urology. 2012;79:95–101.

Irwin DE, Milsom I, Hunskaar S, et al. Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol. 2006;50:1306–14 (discussion 14–5).

Bartoli S, Aguzzi G, Tarricone R. Impact on quality of life of urinary incontinence and overactive bladder: a systematic literature review. Urology. 2010;75:491–500.

Vrijens D, Drossaerts J, van Koeveringe G, et al. Affective symptoms and the overactive bladder - a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2015;78:95–108.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Irwin DE, et al. The impact of overactive bladder, incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life, work productivity, sexuality and emotional well-being in men and women: results from the EPIC study. BJU Int. 2008;101:1388–95.

Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Kopp ZS, et al. The impact of overactive bladder on mental health, work productivity and health-related quality of life in the UK and Sweden: results from EpiLUTS. BJU Int. 2011;108:1459–71.

Sexton CC, Coyne KS, Vats V, et al. Impact of overactive bladder on work productivity in the United States: results from EpiLUTS. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:S98–107.

Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, et al. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:130–40.

Irwin DE, Mungapen L, Milsom I, et al. The economic impact of overactive bladder syndrome in six Western countries. BJU Int. 2009;103:202–9.

American Urological Association. Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults: AUA/SUFU guideline. 2019. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/overactive-bladder-(oab)-guideline Accessed Sep 2020.

Nambiar AK, Bosch R, Cruz F, et al. EAU guidelines on assessment and nonsurgical management of urinary incontinence. Eur Urol. 2018;73:596–609.

Jimenez-Cidre M, Costa P, Ng-Mak D, et al. Assessment of treatment-seeking behavior and healthcare utilization in an international cohort of subjects with overactive bladder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:1557–64.

Kogan MI, Zachoval R, Ozyurt C, Schafer T, Christensen N. Epidemiology and impact of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms: results of the EPIC survey in Russia, Czech Republic, and Turkey. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30:2119–30.

Cornu JN, Amarenco G, Bruyere F, et al. Prevalence and initial management of overactive bladder in France: a cross-sectional study. Prog Urol. 2016;26:415–24.

Sarici H, Ozgur BC, Telli O, et al. The prevalence of overactive bladder syndrome and urinary incontinence in a Turkish women population; associated risk factors and effect on Quality of life. Urologia. 2016;83:93–8.

Al-Badr A, Brasha H, Al-Raddadi R, Noorwali F, Ross S. Prevalence of urinary incontinence among Saudi women. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117:160–3.

Al-Handhl BAKY. Epidemiology of urinary incontinence of women in Tikrit city. Tikr Med J. 2012;18:154–65.

El-Azab A. Clinical and epidemiological criteria of overactive bladder (OAB) among women: a population based study. 2007. https://www.ics.org/Abstracts/Publish/45/000309.pdf. Accessed Sep 2020.

Bahloul M AA, Abo-Elhagag MA, Elsnosy E, Youssef AA. Bahloul M, Abbas AM, Abo-Elhagag MA, Elsnosy E, Youssef AA. Prevalence of overactive bladder symptoms and urinary incontinence in a tertiary care hospital in Egypt. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6:2132–6.

Coyne K, Revicki D, Hunt T, et al. Psychometric validation of an overactive bladder symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire: the OAB-q. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:563–74.

Coyne KS, Zyczynski T, Margolis MK, Elinoff V, Roberts RG. Validation of an overactive bladder awareness tool for use in primary care settings. Adv Ther. 2005;22:381–94.

Shy M, Fletcher SG. Objective Evaluation of Overactive Bladder: Which Surveys Should I Use? Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep. 2013;8:45–50.

Ketola E, Klockars M. Computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) in primary care. Fam Pract. 1999;16:179–83.

Wang Y, Xu K, Hu H, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and impact on health related quality of life of overactive bladder in China. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1448–55.

Zhu J, Hu X, Dong X, Li L. Associations Between Risk Factors and Overactive Bladder: A Meta-analysis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25:238–46.

Milsom I, Stewart W, Thuroff J. The prevalence of overactive bladder. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:S565–73.

Blasco P, Valdivia MI, Ona MR, et al. Clinical characteristics, beliefs, and coping strategies among older patients with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:774–9.

Ricci JA, Baggish JS, Hunt TL, et al. Coping strategies and health care-seeking behavior in a US national sample of adults with symptoms suggestive of overactive bladder. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1245–59.

Burgio KL, Ives DG, Locher JL, Arena VC, Kuller LH. Treatment seeking for urinary incontinence in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:208–12.

Cunningham-Burley S, Allbutt H, Garraway WM, Lee AJ, Russell EB. Perceptions of urinary symptoms and health-care-seeking behaviour amongst men aged 40–79 years. Br J Gen Pract. 1996;46:349–52.

Wyman JF, Harkins SW, Fantl JA. Psychosocial impact of urinary incontinence in the community-dwelling population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:282–8.

WorldBank. Total population, Middle East and North Africa. 2019. https://data.worldbank.org/region/middle-east-and-north-africa?view=chart. Accessed Sep 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for their involvement in the during study.

Funding

This study was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc. Astellas Pharma Inc. funded the rapid service and open access fees required for publication.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing/editorial support for this manuscript was provided by K. Ian Johnson, BSc, and Tyrone Daniel, PhD, of Bioscript, Macclesfield, UK; this support was funded by Astellas Pharma Inc.

Authorship

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, provided critical review of the manuscript and its contents, and approved the final manuscript. In addition, all authors act as guarantors for its contents.

Prior Presentation

This study was presented in part at the 35th Annual EAU Congress, Virtual, 17–26 July 2020.

Disclosures

Prof. Yousfi Mostafa Jamal has received professional fees from Astellas Pharma Inc. At the time of study preparation, conduct and writing of this manuscript, Mohamed Soliman was a full-time employee working in Medical Affairs Department at Astellas Pharma Inc. Dr. Al Edwan, Dr. Mohamed Salah Abdelazim and Dr. Salim E. Salhab have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted with ethical approval and informed consent, and in accordance to Helsinki Declaration. The ethics approval procedure differed in each country. The review boards for each country and reference numbers are as: (1) Egypt: Central IRB at Egyptian Ministry of Health; 15–2018/19; (2) Jordan: IRB at School of Medicine, University of Jordan; 1692/2018/67; (3) Algeria: IRB at EHU Oran Algeria and Central IRB notification to Algerian Ministry of Health; 11–07-2018; (4) Lebanon: IRB at Lebanese Hospital Geitaoui University Medical Centre; 2018-IRB-010. No patients were involved in the study trial design or dissemination of results.

Data Availability

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant level data, trial level data and protocols from Astellas sponsored clinical trials at www.ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com. For the Astellas criteria on data sharing see: https://ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Al Edwan, G., Abdelazim, M.S., Salhab, S.E. et al. The Prevalence of Overactive Bladder Symptoms in Women in Algeria, Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon: A Cross-Sectional Population-Based Survey. Adv Ther 38, 1155–1167 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01588-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01588-4