Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated, chronic, inflammatory disease, which has a substantial humanistic and economic burden. This study aimed to assess the impact of this disease on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity, and direct and indirect costs from a societal perspective among Brazilian patients.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study, enrolling patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis according to physician evaluation. Data collection was performed from December 2015 to November 2016 through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire and five standardized patient-reported outcomes instruments. Direct costs were estimated by multiplying the amount of resources used (12-month recall period) by the corresponding unit cost. Indirect costs were grouped in two time horizons: annual costs (income reduction and absenteeism) and lifetime costs (demission and early retirement).

Results

A total of 188 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis were included, with mean age of 48.0 (SD 13.1). “Anxiety and depression” and “pain and discomfort” were the most impaired dimensions, according to the EuroQol Five-Dimension-Three-Level (EQ-5D-3L). The highest effect was found for “symptoms and feelings” [mean (SD) 2.4 (1.7)] Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) subscale. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) presence and biologic-naïve status were associated with worse HRQoL. Presenteeism was more frequent than absenteeism, according to the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire-General Health (WPAI-GH) [17.4% vs. 6.3%], while physical demands and time management were the most affected Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ) subscales [means (SD) 23.5 (28.5) and 17.7 (24.9), respectively]. The estimated annual cost per patient was USD 4034. Direct medical costs accounted for 87.7% of this estimate, direct non-medical costs for 2.4%, and indirect costs for 9.9%.

Conclusions

Results evidenced that moderate to severe plaque psoriasis imposes substantial costs to society. Our data showed that this disease negatively affects both work productivity and HRQoL of Brazilian patients. Subgroups with PsA and biologic-naïve patients presented lower HRQoL, showing the impact of this comorbidity and the relevance of biologics in psoriasis treatment.

Funding

Novartis Biociências S.A.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated, chronic, inflammatory disease, which usually affects skin but also can affect joints and nails [1,2,3]. Worldwide estimates of the prevalence of psoriasis range from 0.51% to 11.43% in adults and from 0% to 1.37% in children [4]. In Brazil, its prevalence is estimated at 1.31% [5]. The disease may present several forms of clinical manifestation with plaque psoriasis, or psoriasis vulgaris, the most frequent of them, accounting for about 90% of cases [2].

Psoriasis treatment includes topical therapy (corticosteroids, vitamin D3 analogs), phototherapy, conventional systemic drugs (acitretin, methotrexate, or cyclosporine), biologics, over-the-counter medications, and complementary or alternative therapies [6]. About 70% and 80% of patients have mild psoriasis that can be controlled using topical therapies alone [2]. A combination of phototherapy and systemic therapy is needed for patients with moderate to severe disease. Biologics are generally used after phototherapy and when conventional systemic therapies have failed, i.e., either they were not tolerated or were contraindicated [2].

Psoriasis has been associated with substantial humanistic burden, markedly an adverse impact on a patient’s quality of life [7]. In particular, patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis have been consistently described as having physical discomfort, impaired emotional functioning, negative body image and self-image, as well as limitations in daily activities and social interaction [7]. Furthermore, several important diseases occur more often in patients with psoriasis than expected on the basis of their respective prevalence in the general population [2], with special relevance to psoriatic arthritis (PsA), Crohn’s disease, cancer (lymphoma and skin cancer), depression, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disorders [2].

Psoriasis also leads to an economic burden for the patients, their families, the health system, and society in general [6, 8,9,10]. As a chronic disease that runs throughout adulthood and the economically productive time of life, it demands not only costs directly related to its diagnosis and treatment but also societal costs, such as loss of productivity [8]. Studies have shown that patients with moderate to severe psoriasis present productivity losses, comprising absenteeism, presenteeism, early retirement, changes of occupation, and work adaptations [6, 9, 10].

To our knowledge, to date there are few published studies that assessed the humanistic and/or economic impact of psoriasis in Brazil [11, 12]. Hence, this study aimed to assess the impact of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), work productivity, and direct and indirect costs from the societal perspective among Brazilian patients.

Methods

Study Design and Eligibility Criteria

This was a cross-sectional, observational, multicenter study performed in ten dermatology medical centers specialized in the treatment of psoriasis in southern and southeastern regions of Brazil. Patients attending routine follow-up visits were consecutively invited to participate in the study. Eligible patients were those able to provide informed consent and to understand and communicate with the investigator, aged at least 18 years old, and with diagnosis of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis according to physician evaluation. Patients who had been enrolled in clinical trials 12 months prior to study enrollment were excluded.

Data Collection

Eligible patients were invited to a face-to-face interview, conducted by a trained healthcare provider. Before the interview, patients received the required information about the study protocol and those who agreed to participate have read and signed the Informed Consent Form. During the interview, the following standardized patient-reported outcomes were used for data collection: Dermatology Life Quality Index questionnaire (DLQI), EuroQol Five-Dimension-Three-Level (EQ-5D-3L), The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire-General Health (WPAI-GH), and Work Limitations Questionnaire (WLQ). In addition, patients answered one questionnaire specifically developed for the study about variables concerning sociodemographic aspects, lifestyle behaviors, clinical characteristics, and health resource utilization/costs. Data collection was performed between December 2015 and November 2016.

HRQoL

HRQoL data were obtained through DLQI and EQ-5D-3L questionnaires. DLQI is composed of ten questions concerning patients’ perception of the impact of skin disease on different aspects of their HRQoL over the last week. Those questions can be categorized (and analyzed) under six subscales as follows: symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work or school, personal relationships, and treatment. Each question is scored on a 0–3 Likert scale that demonstrates the impact of psoriasis on each subscale: “Not at all/Not relevant”, score = 0; “A little”; score = 1, “A lot”, score = 2; “Very much”, score = 3. The summed DLQI score ranges between 0 and 30 and they are categorized as follows: 0–1 = no effect at all on the subject’s life; 2–5 = small effect on the subject’s life; 6–10 = moderate effect on the subject’s life; 11–20 = very large effect on the subject’s life; and 21–30 = extremely large effect on the subject’s life [11, 13, 14].

EQ-5D-3L is a generic instrument to evaluate quality of life, analyzing the impact of health conditions through five domains (mobility, personal care, general activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression). For each domain, the patient uses his/her perception for classification into the following levels: no problems, some problems, or extreme problems [15, 16]. Each of the health states is converted into a utility score between 0 and 1 (representing a scale between death = 0 and perfect health = 1), using the UK algorithm [17]. EQ-5D-3L also contains a visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) which records the patient’s self-reported health status from 0 (worst imaginable) to 100 (best imaginable) [15, 16].

DLQI and EQ-5D-3L data were presented for total sample and also for subgroups of patients according to the use of biologic drugs in the last 12 months (biologic-experienced—patients who reported the use of biologic drugs vs. biologic-naïve patients—patients who did not report the use of biologic drugs) and the diagnosis of PsA.

Presence of Depression and Anxiety

The HADS was used to evaluate the presence of depression and anxiety symptoms. This questionnaire includes 14 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 21. Responses are categorized concerning the levels of observed symptomatology, for both subscales, as follows: normal (0–7 points), mild (8–10 points), moderate (11–14 points), and severe (15–21 points) [18,19,20,21].

Productivity Losses

Productivity losses were assessed by using the WPAI-GH and the WLQ instruments.

WPAI-GH was developed to evaluate the impact of health problems on the subject’s productivity, in paid or unpaid activities, in the last 7 days [22, 23]. This questionnaire contains six questions that can afford four scores expressed in percentages: percentage of working time missed due to the disease (absenteeism); percentage of impairment during work due to the disease (presenteeism); general percentage of impairment score during work due to the disease (absenteeism and presenteeism); and percentage of daily activity impairment due to the disease [24, 26]. High scores indicate greater disease impact on productivity [22, 23]. Only patients with current professional activity were assessed for absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment. All patients were assessed for daily activity impairment.

WLQ evaluates lost productivity through the proportion of time affected by work limitations due to the disease (both presenteeism and absenteeism) in the last 2 weeks [25, 26]. This instrument comprises 25 items, grouped in four subscales: time management (five items addressing difficulty handling time and scheduling demands); physical demands (six items about a person’s ability to perform work tasks that involve bodily strength, movement, endurance, coordination, and flexibility); mental/interpersonal demands (nine items: six items pertain to difficulty performing cognitive job tasks and/or tasks involving the processing of sensory information and three items address challenges in interacting with people at work); and output demands (five items concerning decrements in a person’s ability to meet demands for quantity, quality, and timeliness of completed work) [25, 26].

Responses for each item are categorized using a 5-point Likert scale that examines the proportion of time with difficulty: “none of the time (0%)”, score = 0; “a slight bit of the time”, score = 1; “some of the time (50%)”, score = 2; “most of the time”, score = 3; “all of the time (100%)”, score = 4; plus a “does not apply to my job” option (treated as missing, no score). The physical demands subscale has reverse instruction and examines the proportion of time without difficulty [26]. The mean value of each dimension is scored separately and converted into a 0–100 scale, in which higher scores represent larger limitations [25]. A conversion table for the WLQ Productivity Loss index was used to calculate the productivity impact of health-related work limitations either in terms of percentage decrease in productivity (compared to healthy individuals) or as a percentage increase in work hours needed to compensate for loss of productivity [26].

Resource Utilization and Costs

During the interview, patients reported their health-related resource utilization (in terms of frequency of use of selected medical resources: outpatient visits, lab tests, treatments for psoriasis, inpatient admissions, etc.), considering a 12-month recall period. Direct costs (medical and non-medical) related to disease management were estimated by multiplying the amount of resources used by the corresponding unit cost.

Indirect costs (those related to productivity losses) were grouped in two time horizons: (1) annual costs: related to the occurrence of health events in which disease impaired the patient’s work productivity during a particular period of time (income reduction and absenteeism); (2) lifetime costs: occurrence of health events in which disease impaired the patient’s work productivity during their lives (demission and early retirement).

Sources of unit costs and equations of costs calculations are described in Table 1. All data were collected in Brazilian real (BRL) and converted to United States dollar (USD), using the exchange rate from 08/Mar/2017—1 USD = 3.15 BRL.

Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was estimated on the basis of the impact of moderate to severe psoriasis on the patient’s HRQoL by using the DLQI questionnaire. A descriptive approach was used, once there is no hypothesis to be tested.

Considering a standard deviation equal to 6.9, based on previous studies which evaluated the impact of psoriasis on patients’ quality of life using the DLQI questionnaire [6, 27], and considering an acceptable error of 1.0 point, 188 patients would be necessary to achieve a robust estimation of the population mean (95% confidence interval, level of significance 0.05).

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained were tested for normal distribution using Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. To compare means, the variables with normal distribution were analyzed by the Student’s t test, and those with non-normal distribution were analyzed by Mann–Whitney nonparametric test. To assess possible differences between frequencies of categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. In 2 × 2 cross-tables, the expected values smaller than 5 may affect an approximation of the chi-square; in this case Fisher’s exact test was used. Stata MP 12® and R Project 3.1.2©statistical software were used, assuming a significance level of 5%.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The research was reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees of each participating research site (see supplementary material). The master ethics committee was at the Hospital do Servidor Público Municipal—SP (the research site was the Hospital do Servidor Público Municipal, São Paulo; approval number 1,317,851). All procedures are in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Results

Sociodemographic Aspects, Lifestyle Behaviors, and Clinical Characteristics

This study included 188 patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and the mean age at study visit was 48 years. Most of them were female, Caucasian/white, and married/stable union.

Among patients who smoke/drink or quit smoking/drinking, the majority of them reported that disease had no impact on these behaviors; the most frequent answers were “My smoking habits changed for another reason” and “I’ve kept my alcohol consumption”.

Regarding clinical characteristics, mean age at diagnosis was 33 years, with mean time between first symptoms and medical diagnosis of 2.1 (SD 3.9) years. The most frequent comorbidities were hypertension, dyslipidemia, PsA, obesity, anxiety, diabetes mellitus and depression. Conventional systemic drugs and biologics were reported to be used by approximately 54% and 30% of patients, respectively.

Details on sociodemographic aspects, lifestyle behaviors and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

HRQoL

All patients answered the DLQI (n = 188) and 76.4% reported some impact of psoriasis on HRQoL. Moderate to extremely large impairment of psoriasis on HRQoL was reported by 68.8% of patients. The highest effect was found for “symptoms and feelings” [mean (SD) 2.4 (1.7)] and the lowest in “work or school” [mean (SD) 0.4 (0.8)] DLQI subscales. The mean DLQI score was 7.2 (SD 6.8) (Table 3).

According to the use of biologics, 42.2% (n = 24/57) of patients who experienced treatment with biologics presented no disease effect on HRQoL, compared to 19.8% (n = 26/133) of biologic-naïve patients (p = 0.014). The highest effect was found for the “symptoms and feelings” DLQI subscale [biologic-experienced mean (SD) 2.0 (1.8); biologic-naïve mean (SD) 2.5 (1.7)], with a statistically significant difference between both groups (p = 0.017) (Table 3).

The subgroup of psoriasis patients with PsA concomitantly presented a worse HRQoL when compared with the subgroup of patients without this comorbidity, with a statistically significant difference in the DLQI scores [PsA patients mean (SD) (n = 45) 9.4 (7.6); non-PsA patients mean (SD) (n = 143) 6.5 (6.4); p = 0.026].

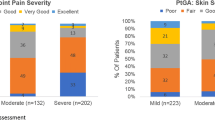

The EQ-5D-3L obtained valid responses for 176 patients (93.6%). Mean EQ-5D-3L index was 0.70 (SD 0.27), with “anxiety and depression” and “pain and discomfort” as the most impaired domains (Fig. 1 and Table 4). Overall score of EQ-5D VAS was 68.7 (SD 22.3). Biologic-experienced patients presented numerically higher EQ-5D-3L index compared to biologic-naïve patients, although without statistical significance [means (SD) 0.76 (0.23) vs. 0.67 (0.28), respectively; p = 0.089]. Exposure to biologic treatment was not associated with statistically significant differences in the proportion of problems in the EQ-5D-3L dimensions, but only biologic-naïve patients were reported to have extreme problems in “usual activities”, “self-care”, and “mobility” (Fig. 2). In addition, biologic-experienced patients showed better results in EQ-VAS overall score than biologic-naïve patients [means (SD) 73.4 (17.5) vs. 66.6 (23.9), p = 0.150].

Presence of Depression and Anxiety

Specifically regarding anxiety and depression, all patients completed the HADS questionnaire (n = 188). Anxiety mean score was 8.1 (SD 4.6), and 96 patients (51%) presented anxiety symptoms. Depression symptoms were reported by 27.1% of patients and the mean score was 5.3 (SD 4.1). In terms of severity, frequencies of normal, mild, moderate, and severe symptoms were 49.0%, 18.6%, 23.4%, and 9.0% for anxiety and 72.9%, 15.4%, 9.0%, and 2.7% for depression, respectively.

Productivity Losses

The mean daily activity impairment was 25.7% (SD 29.5). Work impairment was more attributable to presenteeism [mean (SD) 17.4% (5.5%)] than to absenteeism [mean (SD) 6.3% (13.8%)]. Considering WLQ answers (n = 112), physical and time demands were the most affected subscales [means (SD) 23.5 (28.5) and 17.7 (24.9), respectively). The mean WLQ index was 4.7 (SD 5.4), which means that patients in this sample would need to increase approximately 5% in work hours to compensate for productivity losses (compared to healthy population) (Table 5).

Health Resources Utilization and Costs

The estimated total annual costs of moderate to severe psoriasis were USD 758,467, with a mean of USD 4034 per patient (Table 6). Direct medical costs accounted for the highest proportion of the total costs (87.7%), followed by indirect costs (9.9%) and direct non-medical costs (2.4%).

Direct annual medical costs summed USD 665,167 (USD 3538 per patient), drug therapy being responsible for 97.6% of those costs. Regarding frequency of utilization, drug therapy and outpatient visits were the most consumed direct medical resources (99.5% and 96.3%, respectively). The majority (99.4%) of patients reported having visited physicians and 22.1% other healthcare providers. Dermatologist was the most frequent outpatient visit (98.9%; n = 178/180) among physicians, with a mean of 5.4 visits per year per patient; while psychologist was the most frequent (42.5%; n = 17/40) outpatient visit among other healthcare providers. Despite the high frequency of outpatient visits, this resource accounted for only 0.7% of total medical direct costs.

Direct non-medical costs were USD 122 per patient (total costs of USD 18,350—2.4%), transportation accounting for 70.5% of the costs, summing USD 12,929 (USD 87 per patient). In terms of frequency of utilization, transportation and food expenses were the non-medical resources reported by the most of patients (78.7% and 75.5%, respectively).

Costs per patient segmented by direct medical costs, direct non-medical costs, and indirect costs are shown in Table 6. Costs related to lifetime productivity loss were not included in the figure, as they are not calculated on a yearly basis. However, lifetime productivity losses for the sample summed USD 649,691 (considering demission—USD 131,428 and early retirement—USD 518,263).

Discussion

In order to assess the impact of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis on HRQoL and its associated costs among Brazilian patients, this study interviewed 188 patients from ten dermatology medical centers specialized in the treatment of psoriasis in southern and southeastern regions of Brazil.

Our findings from the EQ-5D-3L instrument are consistent with other psoriasis studies as reported by Møller et al. in their systematic review to understand the disutility of patients with plaque psoriasis [28]. They included 12 studies, nine of which evaluated patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis; EQ-5D utility index scores ranged from 0.52 (SD 0.39) to 0.9 (SD 0.1), corroborating our findings [mean (SD) 0.70 (0.27)]. Moreover, considering the use of previous biologic agents, biologic-experienced patients had a slightly higher score than biologic-naïve patients; however, no statistical significance was found [means (SD) 0.76 (0.23) vs. 0.67 (0.28), respectively; p = 0.089]. Comparing with the Brazilian general population, our psoriasis patients showed a worse HRQoL in terms of EQ-VAS results (means 82.1 vs. 68.7, respectively) [29].

DLQI mean score [mean (SD) 7.2 (6.8)] is also in line to what has been observed in other international studies [30,31,32,33]. It is important to note that according to the defined classes of DLQI (0–1, no effect; 2–5, slight effect; 6–10, moderate effect; 11–20, very large effect; 21–30, extremely large effect), the impact of moderate to severe psoriasis on patients’ quality of life was on average moderate. Meyer et al., who performed a cross-sectional study with 590 French patients with psoriasis, found a mean DLQI score of 8.5 for patients with severe psoriasis and 6.4 for patients with mild psoriasis (p = 0.002) [34]. Another study that included 100 patients from Serbia, 40% with severe and 25% with moderate psoriasis, found a mean DLQI score of 10.5 (SD 7.2) [31]. Similarly, the highest effect was found for “symptoms and feelings”, endorsing that emotional aspects play an important role in the quality of life of psoriasis patients, since skin is responsible in large part for an individual’s presentation [30, 31, 34].

This study also pointed out that biologic-naïve patients show a reduced quality of life as compared to biologic-experienced patients. However, the difference among groups was not statistically significant, which may be justified by the sample size in each group. Furthermore, in agreement with overall sample, the highest effect was found for “symptoms and feelings” in both subgroups of patients (biologic-experienced and biologic-naïve), with the patients treated with biologics presenting significant lower values as compared to biologic-naïve patients, reinforcing the importance of biologics in the reduction of the emotional impact of psoriasis. In fact, the use of biologics has been associated with the reduction of DLQI score and, consequently, with the improvement in patients’ quality of life [35].

PsA was reported as comorbidity by approximately one-third of the sample, in accordance with international studies that have shown a range between 6% and 41% [36,37,38]. In agreement with international literature [36, 37], the subgroup of PsA patients presented reduced HRQoL when compared with patients without this comorbidity, highlighting the relevance of this comorbidity in the course of psoriasis [38].

According to the HADS questionnaire, patients presented a higher frequency of symptoms of anxiety than depression (51% vs. 27%, respectively). Moreover, the prevalence of anxiety found in these psoriasis patients was higher than in the Brazilian general population. A study conducted in a primary care setting in Brazil observed that the prevalence of anxiety using the HADS questionnaire ranged from 35.4% to 43.0% in four state capitals (Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, Fortaleza, and Porto Alegre) [39]. In our study, anxiety and depression were also reported as comorbidities by 25.5% and 16.6% of patients, respectively; these values were lower than those found by using the HADS instrument, which may indicate an underdiagnoses of these conditions among this psoriasis sample.

The total annual cost of this psoriasis cohort was estimated at USD 4034 per patient (USD 758,467 for total sample). This data is consistent with the results found in a systematic review of psoriasis costs among five European countries (Germany, Spain, France, Italy, and the UK), which showed that the total annual cost per patient ranged from USD 2077 to USD 13,132 [40]. Although it is important to consider the differences in methodologies when comparing costs with other studies, the cited systematic review reported that the majority of included studies used a methodological approach similar to ours. In this systematic review direct costs accounted for the greatest part of the total cost [40], like in our study.

A high proportion of direct costs in the total cost was also observed in studies performed in Canada [6], Hungary [32], and the USA [41]. Additionally, as has been previously observed [42], despite the high utilization of conventional systemic drugs and topical therapies, considered less expensive treatment, drug treatment was the main healthcare cost driver; whereas emergency visits and hospitalizations accounted for the minor proportions of costs. Some authors argue that the introduction of biologics imposed an economic burden on treatment costs; on the other hand, they seem to have led to a reduction of inpatient admissions; thus they might have a cost-saving effect despite their high unit prices [40, 42, 43]. Driessen et al. conducted a study to assess the economic impact of psoriasis before and after the introduction of biologics. Although a significant increase in total costs was described, a significant decrease in direct costs related to day-care admission was also observed [43]. In the present study, a comparison of costs before and after introduction of biologics was not planned, making it unfeasible to perform this type of analysis.

Transportation was the most cost-consuming direct non-medical resource (70.5% of total direct non-medical costs). This is explained by the utilization of treatments that demand a commute to health services for administration, such as phototherapy and some biologics [30].

Indirect costs accounted for approximately 10% of the total annual costs. These costs have not been frequently recognized by payers; however, according to Boccuzzi, payers should always look beyond the direct costs to measure the total impact of a disease on society [44].

The burden of psoriasis on a patient’s professional life has already been shown in different populations. Psoriasis affects patients’ productivity, work capacity, absenteeism, and job maintenance [8,9,10]. In fact, many patients need to change their job area, responsibilities, and even professions because of prejudice related to psoriasis [10]. In agreement with previous data [12, 45], we observed that presenteeism contributes more to productivity loss than absenteeism. Presenteeism also appeared to be relevant in the study performed by DiBonaventura et al. who assessed the work productivity associated with experiencing psoriasis vs. not experiencing psoriasis, along with varying levels of psoriasis severity, by using the Brazil National Health and Wellness Survey [12]. They found high rates of presenteeism in the population with moderate (23.3%) and severe psoriasis (45.5%) in comparison with mild psoriasis (21.4%), suggesting an economic burden [12]. However, our methodology did not include costs related to presenteeism in the total annual costs. Nevertheless, our study outlined that psoriasis can lead to demission and early retirement, the latter mostly driving lifetime costs.

The main limitations of this study are related to generalization of results because it has included patients treated in specialized psoriasis centers of treatment from south and southeast regions of Brazil and data may not be fully representative of all levels of assistance and may not represent all geographic regions of the country. In addition, the study focused on patients actively seeking care or referred by their primary care medical service provider and may not be extended to those in the general population who are untreated.

Despite these limitations, our study addressed both the humanistic and economic impact of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in a sample of Brazilian patients, being able to give a comprehensive overview of the disease burden for patients, their families, the healthcare system, and society.

Conclusions

This study represents an effort to estimate the economic burden of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Brazil in a real-world setting and it provides valuable health economic information to healthcare decision makers for the determination of resource allocation.

The results evidenced that moderate to severe plaque psoriasis imposes substantial costs to society. Our data showed that this disease negatively affects both work productivity and HRQoL of Brazilian patients. Subgroups with PsA and biologic-naïve patients presented lower HRQoL, showing the impact of this comorbidity and the relevance of biologics in psoriasis treatment.

Emotional aspect was the most impaired domain in both specific and general HRQoL instruments, accompanied by high prevalence of anxiety symptoms in HADS analysis. These findings highlight the importance of mental health in psoriasis patients and the need for investment in a proper and comprehensive treatment.

References

Liang Y, Sarkar MK, Tsoi LC, Gudjonsson JE. Psoriasis: a mixed autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2017;49:1–8.

Boehncke WH, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386:983–94.

Romiti R, Fabrício LHZ, Souza CS, et al. Assessment of psoriasis severity in Brazilian patients with chronic plaque psoriasis attending outpatient clinics: a multicenter, population-based cross-sectional study (APPISOT). J Dermatolog. 2018;17:1–11.

Michalek IM, Loring B, John SM. A systematic review of worldwide epidemiology of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:205–12.

Romiti R, Amone M, Menter A, Miot HA. Prevalence of psoriasis in Brazil—a geographical survey. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e167–8.

Levy AR, Davie AM, Brazier NC, et al. Economic burden of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Canada. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1432–40.

Korte J, Sprangers MAG, Mombers FMC, Bos JD. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:140–7.

Wu Y, Mills D, Bala M. Impact of psoriasis on patientsʼ work and productivity: a retrospective, matched case-control analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:407–10.

Horn EJ, Fox KM, Patel V, Chiou CF, Dann F, Lebwohl M. Association of patient-reported psoriasis severity with income and employment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:963–71.

Chan B, Hales B, Shear N, et al. Work-related lost productivity and its economic impact on Canadian patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:192–7.

Tejada CS, Mendoza-Sassi RA, Almeida HL Jr, Figueiredo PN, Tejada VFS. Impact on the quality of life of dermatological patients in southern Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1113–21.

Dibonaventura M, De Carvalho AVE, Souza CS, Squiassi HB, Ferreira CN. The association between psoriasis and health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health care resource use in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:197–204.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)—a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6.

Martins GA, Arruda L, Mugnaini ASB. Validation of life quality questionnaires for psoriasis patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2004;79:521–35.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of the health-based quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16:199–208.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37:53–72.

Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care. 1997;35:1095–108.

White D, Leach C, Sims R, Atkinson M, Cottrell D. Validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale for use with adolescents. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:452–4.

Hermann C. International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale—a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42:17–41.

Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression (HADS) scale. Qual life Newsl. 1993;6:5.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70.

Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment measure. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4:353–65.

Ciconelli RM, De Soárez PC, Kowalski CCG, Ferraz MB. The Brazilian Portuguese version of the work productivity and activity impairment: general health (WPAI-GH) questionnaire. Sao Paulo Med J. 2006;124:325–32.

Reilly Associates. WPAI Scoring. 2016. http://www.reillyassociates.net/WPAI_Scoring.html. Accessed 18 Oct 2018.

Lerner D, Amick BC, Rogers WH, Malspeis S, Bungay K, Cynn D. The work limitations questionnaire. Med Care. 2000;39:72–85.

Tang K, Beaton DE, Boonen A, Gignac MAM, Bombardier C. Measures of work disability and productivity: rheumatoid arthritis specific work productivity survey (WPS-RA), workplace activity limitations scale (WALS), work instability scale for rheumatoid arthritis (RA-WIS), work limitations questionnaire (WLQ), and work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire (WPAI). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:S337–49.

Martins BDL, Torres FN, De Oliveira MLW. Impact on the quality of life of patients with Hansen’s disease: correlation between dermatology life quality index and disease status [Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2008;83:39–43.

Møller AH, Erntoft S, Vinding GR, Jemec GBE. A systematic literature review to compare quality of life in psoriasis with other chronic diseases using EQ-5D-derived utility values. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:167–77.

Santos M, Cintra MACT, Monteiro AL, et al. Brazilian valuation of EQ-5D-3L health states: results from a saturation study. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:253–63.

Meyer N, Paul C, Feneron D, et al. Psoriasis: an epidemiological evaluation of disease burden in 590 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1075–82.

Timotijević ZS, Janković S, Trajković G, et al. Identification of psoriatic patients at risk of high quality of life impairment. J Dermatol. 2013;40:797–804.

Balogh O, Brodszky V, Gulácsi L, et al. Cost-of-illness in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: a cross-sectional survey in Hungarian dermatological centres. Eur J Heal Econ. 2014;15:S101–9.

Moradi M, Rencz F, Brodszky V, Moradi A, Balogh O, Gulácsi L. Health status and quality of life in patients with psoriasis: an Iranian cross-sectional survey. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18:153–9.

Kossakowska MM, Cieścińska C, Jaszewska J, Placek WJ. Control of negative emotions and its implication for illness perception among psoriasis and vitiligo patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:429–33.

Norris D, Photiou L, Tacey M, et al. Biologics and dermatology life quality index (DLQI) in the Australasian psoriasis population. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28:731–6.

Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology. 2012;51:571–6.

Puig L, Strohal R, Husni ME, et al. Cardiometabolic profile, clinical features, quality of life and treatment outcomes in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26(1):7–15.

Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2015;41:545–68.

Gonçalves DA, Mari JJ, Bower P, et al. Brazilian multicentre study of common mental disorders in primary care: rates and related social and demographic factors. Cad Saude Publica. 2014;30:623–32.

Burgos-Pol R, Martínez-Sesmero JM, Ventura-Cerdá JM, Elías I, Caloto MT, Casado MÁ. The cost of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in 5 European countries: a systematic review. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:577–90.

Schaefer CP, Cappelleri JC, Cheng R, et al. Health care resource use, productivity, and costs among patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:585–93.

Carrascosa JM, Pujol R, Dauden E, et al. A prospective evaluation of the cost of psoriasis in Spain (EPIDERMA project: Phase II). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:840–5.

Driessen RJB, Bisschops LA, Adang EMM, Evers AW, Van De Kerkhof PCM, De Jong EMGJ. The economic impact of high-need psoriasis in daily clinical practice before and after the introduction of biologics. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162:1324–9.

Boccuzzi SJ. Indirect health care costs. In: Weintraub WS, editor. Cardiovascular health care economics. Totowa: Human; 2003. p. 63–9.

Vanderpuye-Orgle J, Zhao Y, Lu J, et al. Evaluating the economic burden of psoriasis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:961–7.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to patients and to staff professionals for their participation in the study.

Funding

Novartis Biociências S.A. (São Paulo, Brazil) funded this study as well as expenses related to the Rapid Service Fee. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Pamela Santana and Arthur Orlando Corrêa Schilithz from ANOVA Health Consulting Group (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) provided assistance with medical writing and statistical analysis, respectively. Services were funded by Novartis Biociências S.A.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Nilcéia Lopes is a full-time employee of, and declares stock holdings and/or stock options in, Novartis Biociências S.A.; Luna Azulay-Abulafia, MD is/has served as a consultant/researcher of Abbvie, Galderma, Janssen, La Roche Posay, Lilly, LeoPharma, Natura, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche; Maria Victoria Suarez, MD participated in Novartis’ CLEAR competition as a group coordinator in 2017 and 2018, she received from Novartis a fee for the classes ministered during the two competitions and will receive a fee for competition manuscript writing of CLEAR, and she has done consulting for Biolab; her site received a fee for conducting the PSIL study, sponsored by Novartis, and participated in conducting clinical studies sponsored by Galderma; Lincoln Fabricio, MD has served as speaker for Abbott/AbbVie, Bayer, Bioderma, Biolab, Boticário, Galderma, Hypermarcas, Isdin, Janssen, La Roche-Posay, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and Stiefel/GSK; has received sponsorship for scientific events from Abbott/AbbVie, Bayer, Bioderma, Galderma, Isdin, Janssen, La Roche-Posay, Leo Pharma, Pfizer MSD, and Novartis, and has participated in advisory boards for Bayer, Janssen, La Roche-Posay, Leo Pharma, and MSD; Clarice Marie Kobata, MD is/has served as a clinical study investigator and participates in preceptorships of Novartis, attends congress and preceptorships of Janssen, drafts manuscripts for AbbVie; Tania Cestari, MD and/or her first-degree relative currently has a financial interest/arrangement, affiliations, or other relationships with a commercial interest, including Grants/Research Funding as Principal Investigator and to her Institution from AbbVie and Vichy Laboratories, honoraria as Speaker from Avène and as Investigator form Janssen-Cilag, Fees as Speaker from Sanofi; Cid Y. Sabbag, MD participates in congress with Janssen and AbbVie; Ricardo Romiti, MD is/has served as a scientific consultant, speaker, or clinical study investigator for AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB; Patricia C. Pertel is a full-time employee of Novartis. Leticia L. S. Dias, Luiza K. M. Oyafuso, Bernardo Gontijo, and João R. Antonio have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The research was reviewed and approved by independent ethics committees of each participating research site (supplementary material). The master ethics committee was at the Hospital do Servidor Público Municipal—SP (the research site was the Hospital do Servidor Público Municipal, São Paulo; Approval number 1.317.851). All procedures are in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9197534.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lopes, N., Dias, L.L.S., Azulay-Abulafia, L. et al. Humanistic and Economic Impact of Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis in Brazil. Adv Ther 36, 2849–2865 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01049-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01049-7