Abstract

Introduction

Few studies have compared adherence between long-acting injectable antipsychotics, especially for newer agents like aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400; aripiprazole monohydrate) and oral antipsychotics, in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder (BD-I) in a real-world setting.

Methods

Two separate retrospective cohort analyses using Truven MarketScan data from January 1, 2012 to June 30, 2016 were conducted to compare medication adherence and discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia or BD-I who initiated treatment with AOM 400 vs. patients changed from one oral antipsychotic monotherapy to another. Adherence was defined as proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 0.80 in the year following the index date. Linear regression models examined the association between AOM 400 and oral antipsychotic cohorts and medication adherence. Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression estimated time to and risk of discontinuation, while adjusting for baseline covariates. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using a combination of propensity score matching and exact matching to create matched cohorts.

Results

Final cohort sizes were as follows—Schizophrenia: AOM 400 n = 408, oral antipsychotic n = 3361; BD-I: AOM 400 n = 413, oral antipsychotic n = 15,534. In patients with schizophrenia, adjusted mean PDC was higher in patients in the AOM 400 cohort vs. the oral antipsychotic cohort (0.57 vs. 0.48 P < 0.001), and patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had a higher risk of discontinuing treatment vs. the AOM 400 cohort (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.29–1.64). For patients with BD-I, adjusted mean PDC was higher for the AOM 400 cohort (0.59 vs. 0.44, P < 0.001), and patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had a higher risk of discontinuation (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.53–1.92).

Conclusions

In a real-word setting, AOM 400 resulted in a significantly higher percentage of patients with a PDC ≥ 0.80 and significantly longer time to treatment discontinuation compared to patients with schizophrenia or BD-I who received treatment with an oral antipsychotic.

Funding

Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder (BD-I) are both chronic psychiatric disorders that affect approximately 2.7 and 5.7 million people, respectively, in the USA [1, 2]. For both disorders, antipsychotic therapy has remained the standard treatment, and effective management of either disorder hinges on the persistent use of antipsychotic medications. As it is the case with many chronic conditions, adherence in patients with psychiatric disorders is often poor [3,4,5]. Estimates for the percentage of nonadherent patients vary considerably and range from 34% to 81% for patients with schizophrenia [6,7,8,9,10,11,12] and 20% to 60% for patients with BD-I [10]. Nonadherence to treatment has the potential to lead to serious consequences, including relapse, increased risk for hospitalization, increased costs, and increased rates of suicide [13, 14].

The advent of newer antipsychotic medications over the last decade has altered the treatment landscape and provided alternatives for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) were developed in part to help address the issues associated with adherence in patients with these disorders [15,16,17]. Currently eight LAI agents are FDA approved for the treatment of schizophrenia [first-generation LAIs: fluphenazine decanoate, haloperidol decanoate; second-generation LAIs: aripiprazole monohydrate (Abilify Maintena®; AOM 400) [18], olanzapine pamoate, paliperidone palmitate 4 week (Invega Sustenna®) [19], risperidone microspheres (Risperdal Consta®) [20], aripiprazole lauroxil (Aristada®) [21], and paliperidone palmitate 12 week (Invega Trinza®) [22] ], and of these, AOM 400 and risperidone LAI are approved for the maintenance treatment of BD-I. AOM 400 is the more recently approved of the two agents (2013 for schizophrenia, 2017 for BD-I) and offers patients a once-monthly alternative that has been shown to be both effective and well-tolerated [23,24,25]. Current treatment guidelines for schizophrenia recommend that clinicians consider LAIs, not only in patients who are inadequately adherent to pharmacological therapy [26,27,28,29,30], but also in patients who prefer such treatment [31]. To date, limited studies exist comparing adherence between the LAIs—especially for the newer agents like AOM 400—and oral antipsychotics, particularly in a real-world setting [32].

To evaluate adherence and time to discontinuation in a real-world setting, two separate retrospective cohort analyses using healthcare insurance claims data were conducted: the first focusing on patients with schizophrenia, and the second on patients with BD-I. The purpose of the study was to compare medication adherence and discontinuation between patients who initiated treatment with AOM 400 and those who changed from one oral antipsychotic monotherapy to another.

Methods

Data Sources and Study Design

The Truven Health MarketScan® Medicaid, commercial, and supplemental Medicare databases were used to identify patients with schizophrenia and BD-I. The MarketScan Medicaid Database contains healthcare claims from approximately 40 million Medicaid enrollees from multiple states. The database includes claims information for inpatient and outpatient services, outpatient prescription drug claims, and information on enrollment/eligibility, long-term care, and other aspects of medical care. In addition to standard demographic variables such as age and gender, the database also includes variables of value to researchers investigating Medicaid populations (e.g., ethnicity, maintenance assistance status, and Medicare eligibility). The MarketScan commercial database includes medical and pharmacy claims for approximately 65 million individuals and dependents covered through employer-sponsored private health insurance plans. The MarketScan Supplemental Medicare Database contains records on approximately 5.3 million retired employees and spouses at least 65 years of age who are enrolled in Medicare with supplemental Medigap insurance paid by former employers. The data used for both analyses were from January 1, 2012 through June 30, 2016. All databases are Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) compliant. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. As this study utilized de-identified administrative claims, IRB approval was not required.

Study Sample

To be included in the schizophrenia cohort, patients were required to have at least one inpatient claim or at least two outpatient claims for schizophrenic disorders [International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code: 295.xx, excluding 295.4x and 295.7x; or 10th Revision (ICD-10-CM) code: F20x, excluding F20.81x] in any diagnosis field of a claim during the study period [identification (ID) period was from January 1, 2013 to June 30, 2015]. Both existing and newly diagnosed patients were eligible for inclusion.

Two mutually exclusive cohorts of patients with schizophrenia were established: the aripiprazole once-monthly 400 mg (AOM 400) cohort and the oral antipsychotic cohort. For the AOM 400 cohort, patients with at least one claim for AOM 400 were identified during the ID period. The earliest occurrence (first date) of a claim for AOM 400 in the ID period was considered the index date. Patients with claims for AOM 400 in the year prior to the index date were excluded. The oral antipsychotic cohort consisted of patients with no claim for an LAI, but who changed from one oral antipsychotic to another oral antipsychotic monotherapy during the ID period [as evidenced by at least one pharmacy claim for an oral antipsychotic drug (see Supplementary Table S1) during the study ID period]. The index date for the oral antipsychotic cohort was the earliest date of the new oral antipsychotic prescription after switching from a previously different oral psychotic agent. The new monotherapy used on the index date was the index oral therapy.

To ensure patients had pre-existing mental illness, the first diagnosis of schizophrenia had to be before or on the index date. Patients were required to be at least 18 years of age and have continuous plan enrollment for the 12-month baseline period and at least 12 months after the index date. Patients were excluded if they had a prescription claim for clozapine during the study period as clozapine is indicated for the treatment of severely ill patients with schizophrenia who fail to respond adequately to standard antipsychotic therapy [33,34,35]. For the Medicaid-specific database, Medicare and Medicaid dual-eligible patients were also excluded, as were patients who did not have pharmacy coverage, did not have mental health coverage information, or had capitated plans, as data for these patients may have been incomplete. Patients were followed for at least 1 year and until the end of enrollment or study end, whichever occurred first.

An analogous identification and selection criteria was applied to patients with BD-I. ICD-9-CM codes used to identify BD-I included 296.0x, 296.1x, 296.4x, 296.5x, 296.6x, 296.7x, 296.8x (excluding 296.82), and ICD-10-CM codes F30.x and F31.x (excluding F31.81).

Baseline Measures

Baseline variables were measured in the 1-year pre-index baseline period. These included age, gender, race (available in Medicaid claims only), insurance type (commercial, Medicare supplemental, and Medicaid), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [36, 37], number of chronic condition indicators [38], somatic comorbidities [obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), hyperlipidemia, and hypertension], somatic medication use (antidiabetic, antianxiety medications, and sedatives or hypnotics), and baseline inpatient hospitalizations or emergency department (ED) visits. The presence of claims for other psychiatric conditions was also evaluated (at least one claim required for depression, anxiety, personality disorder, substance abuse disorder, bipolar disorder for schizophrenia patients, and schizophrenia for bipolar disorder patients).

Outcome Measures

Adherence was measured by proportion of days covered (PDC) in the year immediately following the index date. PDC was determined by taking the number of available days of index therapy and dividing by 365 [39]. For AOM 400, the days supply was set to the minimum time between injections or the labeled dosing schedule (30 days), whichever was lower. For patients receiving oral antipsychotic agents, the days supply as reported on the prescription claim was used for the PDC calculation. Adherence was defined as a PDC ≥ 0.80. Discontinuation was defined as either a switch or gap of at least 60 days of available days supply during the entire follow-up period. Switching was defined as a claim for a non-index therapy within 60 days after index therapy discontinuation date.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to evaluate differences in baseline characteristic between AOM 400 and oral antipsychotic users. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate differences for proportions of categorical variables, and two-sample t tests were used to evaluate differences in means of continuous variables. Linear regression models were used to examine the association between AOM 400 and oral antipsychotic cohorts and medication adherence. Models adjusted for baseline covariates [age, gender, race (white vs. non-white)], CCI, number of chronic indicators, any baseline inpatient hospitalization, presence of psychiatric comorbidities, and any baseline psychiatric or somatic medication use. Kaplan–Meier curves and Cox regression were employed to estimate time to and risks of medication discontinuation, respectively, while adjusting for the baseline covariates mentioned previously.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted and used a combination of propensity score matching and exact matching to identify matched AOM 400 vs. oral cohorts. Each AOM 400 user was matched with two oral antipsychotic users. Specifically, nearest neighbor matching with a caliper of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score [40] was performed, with propensity score estimated using a logistic regression model with AOM 400 user as dependent variable and demographics (age group, gender, and insurance type) and various baseline clinical characteristics as independent variables. The baseline clinical characteristics included modified CCI (excluding DM), number of HCUP chronic conditions, BD-I (or schizophrenia, depending on the condition under consideration), major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety, personality disorder, substance abuse disorder, obesity, type 2 DM, inpatient hospitalization, selected psychiatric medication use, and selected somatic medication use. The psychiatric medications included were antidepressants, antianxiety medications, sedatives or hypnotics, and mood stabilizers (e.g., lithium). The somatic medications included were antidiabetic, lipid-lowering, and antihypertensive medications. Each AOM 400 user was exactly matched with two oral users on age group, gender, and insurance type. AOM 400 users without two matched oral antipsychotic users were excluded. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4.

Results

Patient Selection and Baseline Characteristics

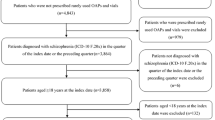

Of the 95,151 patients identified with schizophrenia, 1174 were identified as having a prescription for AOM 400. Once additional inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied, 408 patients remained in the AOM 400 cohort. There were 48,400 patients who received an oral antipsychotic in the ID period and no LAI. After additional study criteria were applied to this cohort, 3361 patients remained. Of the 521,450 patients identified with BD-I, 1117 patients were identified as having a prescription for AOM 400. Once additional study criteria were applied, 413 patients remained in the cohort. Of the 218,733 patients who received an oral antipsychotic in the ID period, 15,534 remained after additional study criteria was applied (Fig. 1). The duration of follow-up was statistically different between cohorts [schizophrenia, mean (SD) days: AOM 400 631.9 (211.7) vs. oral antipsychotic 773.6 (262.6), P < 0.001; BD-I: 625.6 (204.3) vs. 746.7 (260.7), P < 0.001].

Sample selection. After study inclusion/exclusion were applied to identified patients with schizophrenia, 408 (AOM 400 cohort) and 3361 (oral antipsychotic cohort) patients were included in the study sample. In bipolar I disorder, 413 (AOM 400 cohort) and 15,534 (oral antipsychotic cohort) patients were included in the study sample

Differences in baseline characteristics were noted between the AOM 400 cohorts and oral antipsychotic cohorts for both schizophrenia and BD-I patients. Among patients with schizophrenia, AOM 400 patients were significantly younger compared to oral antipsychotic patients (37.3 vs. 43.6 years, P < 0.001). The AOM 400 cohort had a lower percentage of women, but a higher percentage of white and African American patients compared to the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001 for all comparisons; note: race is only available for patients with Medicaid). In both cohorts the majority of patients were on Medicaid. In terms of clinical characteristics, patients with schizophrenia receiving AOM 400 had a significantly lower CCI and fewer chronic conditions, psychiatric comorbidities, and somatic comorbidities than patients receiving oral antipsychotics (P < 0.05 for all). Baseline medication use for psychiatric and somatic conditions was also lower for the AOM 400 cohort with schizophrenia (75.5% vs. 81.8%, P = 0.002), as were hospitalizations in the baseline period (44.6% vs. 54.5%, P < 0.001).

Similar demographic trends were noted for patients with BD-I. Patients in the AOM 400 cohort were younger compared to patients receiving oral antipsychotics (34.0 years vs. 41.5 years, P < 0.001). The AOM 400 cohort also had a lower percentage of women, but a higher percentage of white and African American patients (P < 0.001 for each; note: race is only available for patients with Medicaid, therefore the percentage of patients with “unknown” is higher due to the mix of patients with Medicaid, Commercial, and Medicare Supplemental coverage). The majority of patients in the AOM 400 cohort were on Medicaid (AOM 400 72.9% vs. oral antipsychotic 34.7%), while the majority of patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had commercial coverage (AOM 400 25.9% vs. oral antipsychotic 59.1%, P < 0.001). BD-I patients in the AOM 400 cohort had a higher percentage of patients with psychiatric comorbidities (80.4% vs. 75.5%, P = 0.021), but a lower use of selected psychiatric medications (87.2% vs. 93.5%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Unadjusted Adherence Measures and Time to Discontinuation

During the 1-year post-index follow-up period, patients with schizophrenia in the AOM 400 cohort had a significantly higher percentage of patients adherent to their index medication compared to patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort (33.6% vs. 28.4%, P < 0.001). Unadjusted mean PDC was also significantly higher for the AOM 400 cohort (0.56 vs. 0.45, P < 0.001), and the percentage of patients who switched therapy was significantly lower (75.2% vs. 85.0%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median time to discontinuation was 193 days for the AOM 400 cohort compared to 89 days for the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

The same trends were noted among patients with BD-I. The percentage of patients categorized as adherent was significantly higher for the AOM 400 cohort compared to the oral antipsychotic cohort (35.8% vs. 23.8%, P < 0.001), and the unadjusted PDC was also significantly higher for the AOM 400 cohort (0.58 vs. 0.44, P < 0.001). The percentage of patients who discontinued or switched therapy was significantly lower for the AOM 400 cohort (74.8% vs. 87.7%, P < 0.001) (Table 2). The median time to discontinuation was 224 days for the AOM 400 cohort compared to 84 days for the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Adjusted Adherence Measures and Risk of Discontinuation

In patients with schizophrenia, linear regression and Cox regression models confirmed that after adjusting for differences in covariates, the adjusted mean PDC remained higher in patients in the AOM 400 cohort when compared to the oral antipsychotic cohort (0.57 vs. 0.48, P < 0.001), and patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had a higher risk of discontinuing treatment than patients in the AOM 400 cohort (HR 1.45, 95% CI 1.29–1.64) (Table 3).

Similarly, for patients with BD-I, the adjusted mean PDC was higher for the AOM 400 cohort (0.59 vs. 0.44, P < 0.001), and patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort had a higher risk of discontinuing treatment than patients in the AOM 400 cohort (HR 1.71, 95% CI 1.53–1.92) (Table 3).

Sensitivity Analyses

In the matched cohort analyses for patients with schizophrenia, there were 397 patients in the AOM 400 cohort and 794 in the oral antipsychotic cohort. For BD-I, there were 404 in the AOM 400 cohort and 808 in the oral antipsychotic cohort. After matching, no significant differences were noted for age, gender, or comorbidities for schizophrenia or BD-I, indicating that the matching parameters were successful (Supplementary Table S2).

As was the case in the main analyses, patients with schizophrenia in the AOM 400 cohort had a significantly higher percentage of patients adherent to their index medication compared to patients in the oral antipsychotic cohort (33.0% vs. 27.1%, P < 0.001). Mean PDC was also significantly higher the AOM 400 cohort vs. the oral antipsychotic cohort (0.56 vs. 0.47 P < 0.001). The percentage of patients who discontinued or switched medication followed the same trends, with a lower percentage of patients in the AOM 400 cohort switching or discontinuing (76.1% vs. 86.4%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S3). The median time to discontinuation was 186 days for the AOM 400 cohort vs. 89 days for the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Similar trends were also noted with BD-I patients. The AOM 400 cohort had a significantly higher percentage of patients adherent to index medication vs. the oral antipsychotic cohort (36.4% vs. 22.3%, P < 0.001). Mean PDC for the AOM 400 cohort was 0.58 vs. 0.42 for the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001). A lower percentage of patients discontinued or switched in the AOM 400 cohort vs. the oral antipsychotic cohort (74.5% vs. 87.6%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S3). The median time to discontinuation was 226 days for the AOM 400 cohort vs. 74 days for the oral antipsychotic cohort (P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

This was a large retrospective study that compared medication adherence and discontinuation between patients receiving AOM 400 and patients who changed to a new oral antipsychotic monotherapy in patients with schizophrenia or BD-I in a real-world setting. Patients with schizophrenia who received AOM 400 had a significantly higher PDC and significantly higher percentages of patients who were adherent to therapy during the 1-year follow-up period, had a 104-day-longer median time to medication discontinuation, and were significantly less likely to discontinue their medication during the entire follow-up period than patients who changed to another oral antipsychotic therapy. These trends were also noted in patients with BD-I. Patients receiving AOM 400 had significantly higher PDC, a greater proportion adherent, a 140-day-longer median time to discontinuation, and were significantly less likely to discontinue medication during follow-up. A propensity score matched cohort analysis showed that results were consistent across matched cohorts.

Real-world studies comparing individual LAIs to oral antipsychotics are sparse, particularly for second-generation LAIs. Pilon et al. evaluated the second-generation LAIs (paliperidone palmitate LAI, risperidone LAI, aripiprazole LAI, and olanzapine LAI) with oral antipsychotic agents in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Patients receiving a second-generation LAI were more likely to reach PDC ≥ 0.80 (OR 1.28, P < 0.001) and be persistent (i.e., no gap 60 days or longer) (OR 1.45, P < 0.001) than patients who received oral antipsychotic agents. Comparisons for individual agents varied by agent and by the definition of gap used [41].

Marcus et al. evaluated LAIs on a class level, generation level, and individual agent level (fluphenazine decanoate, haloperidol decanoate, risperidone LAI, and paliperidone palmitate—as the study was published in 2015) as compared to oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia following hospital discharge. Primary outcomes measures were nonadherence (PDC < 0.80), discontinuation, and rehospitalization all in the 6 months following discharge. A significantly smaller percentage of patients receiving LAIs were nonadherent (51.8% vs. 67.7%, P < 0.001). Both first-generation and second-generation LAIs had lower percentages of patients who were nonadherent when evaluated separately compared with patients receiving oral antipsychotics. When individual agents were assessed, patients who initiated paliperidone palmitate had significantly lower rates of rehospitalization [42].

There are several studies that evaluate LAIs as a class versus oral agents that have been published over the years [32, 43,44,45], but many of these studies had a limited follow-up time (within a 1-year period) or small sample sizes. Greene et al. evaluated PDC and time to discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, and found that as a class, LAI users had a 5% higher adjusted mean adherence and were 20% less likely to discontinue medication during follow-up when compared to patients receiving oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia. Similar results were noted in a bipolar disorder population, with patients receiving LAIs having 5% better adherence and being 19% less likely to discontinue therapy [32].

Large, real-world database studies of LAIs consistently show trend towards improved adherence, and many also show reduced resource utilization. However, efficacy results from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been mixed [26, 46]. While some RCTs suggest that treatment with LAIs leads to significant better medication adherence than orals [47, 48], other RCTs suggest that there are no differences in treatment duration or discontinuation between LAIs and orals [49, 50]. Even though RCTs are often considered gold standards for comparing efficacy of different treatments, they may not be best suited for studies of adherence. Compared to real-world studies, patients recruited in RCTs may be less severely ill, have their medication use more closely monitored, and are more likely to be motived to be adherent regardless of treatment [46]. Additionally, RCTs generally have small samples and durations too short to provide meaningful information about drugs that must be taken indefinitely [26].

This study had limitations. First, this is a retrospective, observational study based on pre-existing data. Variables not captured in the database may have influenced the study results. For example, intolerability of the new oral antipsychotic may be responsible for some of the adherence advantage observed in AOM 400. In contrast, patients’ fear or hesitation about injections may have attenuated the advantage of AOM 400. Lack of data on other confounding variables, such as clinical diagnosis of disease, duration of illness, psychometrics, and clinical symptom status, may have also contributed to the differences in adherence to treatment between AOM 400 and oral users. Furthermore, as a result of the observational nature of the study, no causal relationship should be drawn on the basis of the study findings. Second, claims data used for this analysis are generated for reimbursement, not research, and coding errors, misclassification, diagnostic uncertainty, and/or omissions could affect the reliability of the findings. Nevertheless, health insurance claims data remain a valuable source of information because they contain a large and valid sample of patient characteristics in a real-world setting. Third, despite the fact that PDC is a preferred method for measuring medication adherence [32], it has its limitations. For instance, because it requires at least two dispensings, it excludes most nonadherent patients [51]. Additionally, even though the 80% cutoff level is commonly used to define medication adherence in the literature, it is somewhat arbitrary. Further clinical investigation is needed to define appropriate PDC cutoffs for various medications. Finally, a claim for an oral medication is only indicative that a prescription was filled, not that it was actually taken (or taken as prescribed). However, a claim of LAIs is much more reliable than that of oral antipsychotics to indicate that the drug has been actually delivered to the body, which is critical in interpreting any LAI versus oral comparisons.

Conclusions

Medication adherence and persistence are vital to the success in the treatment of patients with psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia and BD-I. Finding alternative therapies and ways to improve adherence can lead to improved outcomes in these populations. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the LAIs have the potential to result in better adherence and lower discontinuation rates. The results of the current study showed that in a real-word setting, an individual LAI agent—AOM 400—resulted in a significantly higher percentage of patients with a PDC ≥ 0.80 and a significantly longer time to treatment discontinuation when compared to patients with schizophrenia or BD-I who received treatment with an oral antipsychotic.

References

The National Institute of Mental Health. Schizophrenia [Internet]. health & education—statistics. 2018. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/schizophrenia.shtml. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

The National Institute of Mental Health. Bipolar disorder [Internet]. Health & education—statistics. 2017. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/bipolar-disorder-among-adults.shtml. Accessed 30 Nov 2017.

Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381:1672–82.

Anderson IM, Haddad PM, Scott J. Bipolar disorder. BMJ. 2012;345:e8508.

Zullig LL, Peterson ED, Bosworth HB. Ingredients of successful interventions to improve medication adherence. JAMA. 2013;310:2611.

Lafeuille M-H, Frois C, Cloutier M, et al. Factors associated with adherence to the HEDIS quality measure in Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016;9:399–410.

Velligan DI, Weiden PJ, Sajatovic M, Scott J, Carpenter D, Ross R, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: adherence problems in patients with serious and persistent mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 4):1–46 (quiz 47–8).

Bright CE. Measuring medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia: an integrative review. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017;31:99–110.

Yang J, Ko Y-H, Paik J-W, et al. Symptom severity and attitudes toward medication: impacts on adherence in outpatients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134:226–31.

García S, Martínez-Cengotitabengoa M, López-Zurbano S, et al. Adherence to antipsychotic medication in bipolar disorder and schizophrenic patients: a systematic review. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;36:355–71.

El-Mallakh P, Findlay J. Strategies to improve medication adherence in patients with schizophrenia: the role of support services. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1077.

De las Cuevas C, de Leon J, Peñate W, Betancort M. Factors influencing adherence to psychopharmacological medications in psychiatric patients: a structural equation modeling approach. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:681–90.

Higashi K, Medic G, Littlewood KJ, Diez T, Granström O, De Hert M. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: factors influencing adherence and consequences of nonadherence, a systematic literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3:200–18.

Sun SX, Liu GG, Christensen DB, Fu AZ. Review and analysis of hospitalization costs associated with antipsychotic nonadherence in the treatment of schizophrenia in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2305–12.

Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, Kramata P, Docherty J. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449–68.

Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14:2–44.

Kane JM, Kishimoto T, Correll CU. Non-adherence to medication in patients with psychotic disorders: epidemiology, contributing factors and management strategies. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:216–26.

Abilify Maintena (aripiprazole) Prescribing Information [Internet]. Rockville: Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2018. https://www.otsuka-us.com/media/static/Abilify-M-PI.pdf.

Invega Sustenna (paliperidone palmitate) Prescribing Information [Internet]. Titusville: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2018. http://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/INVEGA+SUSTENNA-pi.pdf.

Risperdal Consta (risperidone) Prescribing Information. Titusville, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2007.

Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) Prescribing Information [Internet]. Waltham: Alkermes; 2018. https://www.aristadahcp.com/downloadables/ARISTADA-INITIO-PI.pdf.

Invega Trinza (paliperidone palmitate) Prescribing Information [Internet]. Titusville: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2018. https://www.janssenmd.com/pdf/invega-trinza/invega-trinza_pi.pdf.

Biagi E, Capuzzi E, Colmegna F, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: literature review and practical perspective, with a focus on aripiprazole once-monthly. Adv Ther. 2017;34:1036–48.

Calabrese JR, Sanchez R, Jin N, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly in the maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, 52-week randomized withdrawal study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:324–31.

Kane JM, Sanchez R, Perry PP, et al. Aripiprazole intramuscular depot as maintenance treatment in patients with schizophrenia: a 52-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73:617–24.

Correll CU, Citrome L, Haddad PM, et al. The use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: evaluating the evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:1–24.

Jarema M, Wichniak A, Dudek D, Samochowiec J, Bieńkowski P, Rybakowski J. Guidelines for the use of second-generation long-acting antipsychotics. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49:225–41.

Malla A, Tibbo P, Chue P, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics: recommendations for clinicians. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:30S–5S.

Brissos S, Veguilla MR, Taylor D, Balanzá-Martinez V. The role of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a critical appraisal. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4:198–219.

Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management [Internet]. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178.

Greene M, Yan T, Chang E, Hartry A, Touya M, Broder MS. Medication adherence and discontinuation of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. J Med Econ. 2018;21:127–34.

Jing Y, Kim E, You M, Pikalov A, Tran Q-V. Healthcare costs associated with treatment of bipolar disorder using a mood stabilizer plus adjunctive aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine or ziprasidone. J Med Econ. 2009;12:104–13.

Kim E, You M, Pikalov A, Van-Tran Q, Jing Y. One-year risk of psychiatric hospitalization and associated treatment costs in bipolar disorder treated with atypical antipsychotics: a retrospective claims database analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:6.

Berger A, Edelsberg J, Sanders KN, Alvir JMJ, Mychaskiw MA, Oster G. Medication adherence and utilization in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder receiving aripiprazole, quetiapine, or ziprasidone at hospital discharge: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:99.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP chronic condition indicator [Internet]. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). 2015. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp.

Nau D. Proportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence. Alexandria: Pharmacy Quality Alliance; 2012.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399–424.

Pilon D, Tandon N, Lafeuille M-H, et al. Treatment patterns, health care resource utilization, and spending in medicaid beneficiaries initiating second-generation long-acting injectable agents versus oral atypical antipsychotics. Clin Ther. 2017;39:1972.e2–1985.e2.

Marcus SC, Zummo J, Pettit AR, Stoddard J, Doshi JA. Antipsychotic adherence and rehospitalization in schizophrenia patients receiving oral versus long-acting injectable antipsychotics following hospital discharge. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:754–68.

Brnabic AJM, Kelin K, Ascher-Svanum H, Montgomery W, Kadziola Z, Karagianis J. Medication discontinuation with depot and oral antipsychotics in outpatients with schizophrenia: comparison of matched cohorts from a 12-month observational study: medication discontinuation in outpatients with schizophrenia. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:945–53.

Zhu B, Ascher-Svanum H, Shi L, Faries D, Montgomery W, Marder SR. Time to discontinuation of depot and oral first-generation antipsychotics in the usual care of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:315–7.

Kirson NY, Weiden PJ, Yermakov S, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of depot versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: synthesizing results across different research designs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:568–75.

Suzuki T. A further consideration on long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a narrative review and critical appraisal. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13:253–64.

Green AI, Brunette MF, Dawson R, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral risperidone for schizophrenia and co-occurring alcohol use disorder: a randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1359–65.

Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:822.

Buckley PF, Schooler NR, Goff DC, et al. Comparison of SGA oral medications and a long-acting injectable SGA: the PROACTIVE study. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:449–59.

Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:192–213.

Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care. 2013;51:S11–21.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Funding for the study, the open access fee and the article processing charges were received from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. and Lundbeck. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Meg Franklin, PharmD, PhD.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Tingjian Yan is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Michael S. Broder is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Eunice Chang is an employee of PHAR, LLC, which was paid by Otsuka and Lundbeck to perform the research described in this manuscript. Mallik Greene is an employee of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. Ann Hartry is an employee of Lundbeck. Maëlys Touya is an employee of Lundbeck.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Truven Health Analytics but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Truven Health.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital content

To view enhanced digital content for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7028222.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, T., Greene, M., Chang, E. et al. Medication Adherence and Discontinuation of Aripiprazole Once-Monthly 400 mg (AOM 400) Versus Oral Antipsychotics in Patients with Schizophrenia or Bipolar I Disorder: A Real-World Study Using US Claims Data. Adv Ther 35, 1612–1625 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0785-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0785-y