Abstract

Introduction

Switching from any statin to another non-equipotent lipid lowering treatment (LLT) may cause a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol increase and has been associated with a higher probability of negative cardiovascular outcomes. The aim of the study was to assess the impact of switching from rosuvastatin to any other LLT on clinical outcomes in primary care.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis based on data from IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database, which is a general practice database including information of more than 1.0 million patients representative of the Italian population by age, and medical conditions. Patients that started on rosuvastatin (10–40 mg/day) between January 2011 and December 2013 were considered. The date of the first prescription was defined as the index date (ID). The observation period lasted from the ID to September 2015 or until LLT discontinuation, or the occurrence of an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), or death.

Results

The primary end point of the study was the occurrence of an AMI during the observation period. The final study population included 10,368 patients. During the observation period, 2452 (23.6%) patients were switched from rosuvastatin to another LLT. The majority of patients (55.6%) were switched to atorvastatin, followed by simvastatin (24.9%), simvastatin/ezetimibe combination (10.0%) and other statins (9.5%). Female gender (HR, hazard ratio, 1.10, 95% CI, confidence interval, 1.02–1.19, p = 0.04) and the presence of chronic kidney disease (HR 1.47, 95% CI 1.16–1.86, p = 0.05) were associated with a higher probability of switch. During the observation period, 113 patients experienced an AMI (incidence of 6.7 AMI/1000 patient-years). Multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards method, including switching as a time-dependent covariate, demonstrated that changing from rosuvastatin to another LLT was an independent predictor of AMI (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4–3.5, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

We conclude that switching from rosuvastatin to another non-equipotent LLT may impart an increased risk of AMI and should be avoided.

Funding

AstraZeneca SpA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Large-scale observational studies have shown that there is a continuous positive correlation between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations and the incidence of clinical manifestations of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease [1].

Back in 2005, the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration reported a meta-analysis of 14 randomized trials of statin therapy versus control [2]. The results of this analysis showed that lowering of LDL-C by about 1 mmol/L (38 mg/dL) with a standard statin treatment safely reduced the 5-year incidence of major coronary events, revascularizations, and ischaemic strokes by about a fifth [2]. An updated meta-analysis of 26 clinical trials from the same research group, published 5 years later showed that additional reductions in LDL-C achieved with more intensive statin therapy, could further reduce the incidence of major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events [3].

As a matter of fact, statins significantly differ in their potency (LDL-C lowering effect/mg), with rosuvastatin being the most effective agent of this pharmacological class in reducing LDL-C [4]. The usual clinical dosage of 10-40 mg/day of rosuvastatin has been shown to achieve a 46-55% reduction in LDL-C [5].

Recently, the introduction of generic statins has enabled highly cost-effective LDL-C reduction in clinical practice and third party payers often recommend substitution of branded agents with generic alternatives [6]. However, even if switching from brand-name drugs to generic equivalents may reduce prescription costs, it may also potentially compromise therapeutic benefits if generic options are not of equivalent efficacy [7]. In fact, switching from a particular statin to another non-equipotent lipid lowering treatment may alter lipid control by causing a significant LDL-C increase [7, 8]. In line with this observation, switching from more effective to less effective lipid lowering agents has been associated with a higher probability of negative clinical outcomes in high risk clinical conditions [8, 9].

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical impact of switching from rosuvastatin treatment to any other lipid lowering therapy on clinical outcomes in the Italian general practice setting.

Methods

The analysis in this article was based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Source

This was a retrospective analysis based on data extracted from the IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database (Intercontinental Marketing Services Health LPD). The IMS Health LPD is an Italian general practice database in place since 1998 covering more than 1 million active patients. These patients are representative of the Italian population by age, gender, medical conditions and death rates, after adjustment for demographics and social deprivation. The database includes clinical and laboratory information of all patients followed by a group of about 900 general practitioners (GPs), uniformly distributed throughout the whole Italian national territory [10, 11]. These GPs have voluntarily agreed to take part in this research panel, attend specific training courses and use standard software to collect data during consultations. Patient demographic details included in IMS Health LPD are linked through the use of an encrypted patient code with medical records (diagnoses, tests, tests results, therapeutic procedures, hospital admissions), information on drug prescriptions, lifestyle information (alcohol, body mass index, smoking habit), and date of death. In the IMS Health LPD, all diseases are classified according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). To be considered for participation in the IMS Health LPD, GPs must meet up to standard quality criteria pertaining to the levels of coding, prevalence of diseases, mortality rates, and years of recording [12]. Quality and consistency of data collected in the database have been demonstrated and validated through several studies in which the retrieved information has been compared with other current data sources or findings from national surveys [10, 11].

Selection of Study Population and Observation Period

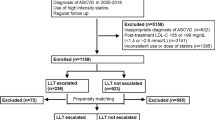

New patients that started on rosuvastatin (10–40 mg/day) between January 2011 and December 2013 were included in the analysis. The date of the first prescription was defined as the index date (ID). For every single patient, the observation period lasted from the ID to September 2015 or until statin treatment discontinuation (i.e., non-exposure to statin therapy for more than 90 days), or the occurrence of an acute myocardial infarction (AMI; ICD-9-CM code 410), or death. To limit the study to initial rosuvastatin prescriptions, patients who had a prescription of rosuvastatin during the 6 months preceding the ID were preliminary excluded. As the Italian Medicines Agency recommends the prescription of high-dose atorvastatin in patients with previous major adverse cardiovascular events, other exclusion criteria were the history of a prior AMI, of a prior stroke, and of any prior revascularization procedure [13]. Besides, “sporadic” patients, i.e., patients with only one prescription of any statin over the entire period of observation, as well as patients treated with low-dose rosuvastatin (i.e., 5 mg/day) were also excluded from the analysis.

Primary End Point

The primary end point of the study was the occurrence of an AMI during the observation period.

Patients were considered to have experienced an AMI (ICD-9-CM code 410) when such an event was recorded in the IMS Health LPD. This specific end point was chosen as it is clinically relevant, easily ascertainable from clinical records and hospital discharge documents [14], and potentially sensitive to more intensive lipid lowering therapy [3, 15]. Besides, a “universal definition” for AMI is currently available, which has also been endorsed by all Italian scientific and professional associations [16]. Other major cardiovascular events do not share the same degree of reliability in terms of clinical diagnosis and coding in primary care and could be underreported [17].

Statistical Analysis

Means (±standard deviation) were calculated for continuous variables, while frequencies were measured for categorical variables.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were applied to identify clinical and demographic variables associated with rosuvastatin therapy switching over the observation period.

Multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were also used to assess the impact of switching from rosuvastatin to any other lipid lowering therapy on the occurrence of the primary end point. As patients could switch from the initially prescribed treatment (rosuvastatin 10–40 mg/day) to any other lipid lowering treatment at any moment during the observation period, Cox models for the association of switching with the primary end point included switching as a time-dependent covariate. This approach has already been employed in similar previous studies [8, 18] because patients can be moved from one risk class to another at the moment of documented modification of pharmacological treatment. Besides, in multivariable analyses, Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to assess the independent association between rosuvastatin switching and the primary end point adjusting for patient demographics (age and gender), clinical history features [hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (CKD)] and pharmacological treatments [insulin, oral hypoglycemic agents, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, anti-platelet, beta blockers, angiotensin II receptor blockers and calcium blockers].

The assumption of proportionality for Cox models was tested and met for all covariates. The results of the Cox proportional hazards models are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

All the analyses have been performed using SAS® software version 9.4, Copyright © [2002–2012] SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Results

The final study population included 10,368 new patients that started on “high-intensity statin treatment” [19] with rosuvastatin (10–40 mg/day) in the period between January 2011 and December 2013 according to the inclusion criteria.

During the entire period of observation, 2452 (23.6%) patients were switched from rosuvastatin to another lipid lowering treatment. Most of the patients were switched to atorvastatin (55.6%), followed by simvastatin (24.9%), simvastatin/ezetimibe (10.0%) combination and other statins (9.5%). Besides, in the vast majority of cases this therapeutic substitution could be considered as non-equipotent in terms of LDL-C reduction and according to current definitions [19], most patients (1777; 72.4%) were switched to “medium” or “low intensity” statin treatment (10–20 mg/day of atorvastatin in 1042 patients; 42.5%; 10–20 mg/day of simvastatin in 502 patients; 20.4%; other low-potency statin agents, such as pravastatin and lovastatin in 233 patients; 9.5%).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population at baseline are reported in Table 1 showing significantly higher percentages in switched patients for most of the analyzed variables; in particular, more patients in the switch group had a history of hypertension or CKD, were taking ACE inhibitors, diuretics or antiplatelet drugs (p value <0.0001).

According to multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards method, factors independently associated with a higher probability of switch during the observation period were female gender (HR = 1.10, 95% CI: 1.02–1.19) and the presence of chronic kidney disease (HR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.16–1.86).

As to the primary end point, during the observation period, 113 patients experienced an AMI, with an overall incidence of 6.7 AMI/1000 patient-years.

The incidence of AMI in patients remaining on rosuvastatin was 6.3 AMI/1000 patients-years (87 events), while it was 8.3 AMI/1000 patient-years (27 events) in patients switched to other lipid lowering therapies.

Multivariate analysis with Cox proportional hazards method, including switching as a time-dependent covariate demonstrated that after adjustment for all available demographic and clinical variables, treated hypertension (HR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9, p = 0.02), female gender (HR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8, p = 0.002) and changing from rosuvastatin to another lipid lowering therapy (HR 2.2, 95% CI 1.4–3.5, p = 0.001) were independent predictors of AMI.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the rate and potential clinical risk of switching from the most effective available statin agent to another lipid modifying intervention in a primary care setting.

The analysis of a large primary care electronic medical record data resource revealed a surprisingly high rate of treatment substitution. More than 23% of patients were switched from the initially prescribed rosuvastatin 10–40 mg/day to another lipid lowering treatment during the observation period, without any evident clinical explanation. Actually, the decisions to switch from rosuvastatin to a potentially less effective intervention were taken by GPs, while the reasons for such a course of action in individual patients are not reported in the database. The only demographic and clinical factors associated with a higher probability of switching were female gender and presence of CKD. In particular, the higher likelihood of switch in patients with CKD suggests that safety concerns may have played a role in some instances [20]. Still, owing to the relatively low prevalence of renal disease in the study population (only 2%), such condition may have had just a limited impact on the overall results. As to female gender, published reports indicate that women may show an increased risk of developing muscle-related adverse symptoms associated with statin use [21]. Consequently, it is quite conceivable that some of the therapeutic substitutions, at least in women, may have been driven by side effects. Anyway, when considering the overall frequency of switching in the study population, it seems clear that the decision to change lipid- lowering therapy cannot be solely explained by plain clinical reasons. This appears even more evident when we take into account both the efficacy and the reassuring safety of rosuvastatin in clinical studies [22]. Moreover, no major potentially statin-related adverse clinical events (i.e., rhabdomyolysis or acute renal failure) have been recorded in the database for the study population.

In Italy, medication costs for cardiovascular prevention are covered by the National Health Service. However, similar to other European countries [23], Italian national and local Health Authorities have promoted specific policies in favor of switching from branded statins to generic alternatives during the study period (2011–2015) [13, 24]. It seems highly probable that these cost-cutting policies may have had a role in encouraging GPs to switch from rosuvastatin to other pharmacological agents, even in the absence of any significant clinical issue.

Another point of major interest emerging from this study is that switching from rosuvastatin treatment to other lipid lowering therapies was associated with a twofold higher probability of AMI during the observation period. Such relevant increase in cardiovascular risk was independent from all major demographic and clinical features. This result is consistent with previously reported observations supporting the notion that switching from more effective to less effective lipid lowering interventions may impart a higher probability of negative clinical outcomes in high risk clinical conditions [8]. Moreover, this evidence is also coherent with data from specific computer simulated clinical trials on rosuvastatin [9]. Overall, clinical studies have clearly shown that both LDL-C levels and cardiovascular outcomes are directly related to statin potency and dosing [2, 3].

In this study, most patients experienced a non-equipotent switch to less effective doses of less potent agents, clearly moving from “high” to “medium” or even “low” intensity statin therapy [19]. Even if LDL-C levels are not available in our series, it is reasonable to assume that this undue therapeutic modification may have altered lipid profile, thereby favoring a negative outcome. However, given the wide variety of different agents and dosages used for the therapeutic substitution, it is difficult to speculate about the real amount of LDL-C rise occurring in patients switched from rosuvastatin to other lipid lowering interventions.

Current clinical guidelines for cardiovascular prevention are clear in their recommendations regarding statin therapy and treatment targets [25]. In fact, clinical trials have shown that statins are more effective than placebo in reducing cardiovascular events, while for the same purpose an intensive statin therapy is more effective than a moderate one [2, 3]. Besides, the lowest risk is associated with the lowest LDL-C levels [2, 3, 15]. However, in clinical practice, patients at high cardiovascular risk are prone to be undertreated, while observational studies suggest that mandatory statin substitution may increase the gap between achieved and recommended therapeutic targets [23, 26]. In general, all statin interchange programs promoting the use of non-equipotent agents have been invariably associated with unfavorable patient outcomes [26–28].

Overall, the results of this study confirm all the previous observational studies on the negative implications of non-equipotent switch on clinical cardiovascular outcomes.

Limitations of the Study

This study has some limitations. First, although this study was conducted using detailed patient and prescription data, patient exposure to the drugs was obtained from the prescription records of GPs. Consequently, it is possible that medication use in the study population was overestimated.

Second, information on LDL-C levels before and after rosuvastatin switch were not available in the database. For this reason we can only hypothesize that switching from a high-intensity rosuvastatin therapy to another less effective agent was associated with a rise in LDL-C. Moreover, as already pointed out, specific reasons for switch are not known and can only be inferred.

Third, the size of the study population was based on the availability of patients with specific features in an already existing database, rather than on statistical considerations. We attempted to account for the potential selection bias as much as possible using multivariable time-dependent covariate adjustment models. Actually, in our multivariable models we considered more than 12 variables, including demographic characteristics, and clinical historical features. However, several other potentially relevant variables that could affect outcomes were not collected or evaluated, while there is just no assurance that any statistical adjustment can be guaranteed as fully precise. As a matter of fact, as in all observational investigations, we cannot exclude that our results might have been partially conditioned by some form of unmeasured confounding.

Finally, as a retrospective observational study, it is not possible to demonstrate a cause-effect relation between switch and AMI.

Conclusions

We conclude that switching from rosuvastatin to another, potentially less effective, lipid lowering treatment may impart an increased risk of experiencing an AMI and should be avoided unless strictly necessary on clinical grounds. Moreover, this analysis supports the assertion that cost-containing therapeutic substitution programs should always employ clinically equivalent treatment alternatives.

References

Prospective Studies Collaboration. Blood cholesterol and vascular mortality by age, sex, and blood pressure: a meta-analysis of individual data from 61 prospective studies with 55.000 vascular deaths. Lancet. 2007;370:1829–39.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90.056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005; 366:1267–78.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170.000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010; 376:1670–81.

ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–818.

Adams SP, Sekhon SS, Wright JM. Lipid-lowering efficacy of rosuvastatin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 11:CD010254.

Willey VJ, Reinhold JA, Willey KH, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes in patients switched to simvastatin in a community-based family medicine practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64:1235–8.

Hess G, Sanders KN, Hill J, Liu LZ. Therapeutic dose assessment of patient switching from atorvastatin to simvastatin. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(Suppl 3):S80–5.

Colivicchi F, Tubaro M, Santini M. Clinical implications of switching from intensive to moderate statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2011;152:56–60.

Colivicchi F, Sternhufvud C, Gandhi SK. Impact of treatment with rosuvastatin and atorvastatin on cardiovascular outcomes: evidence from the Archimedes-simulated clinical trials. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:555–65.

Cricelli C, Mazzaglia G, Samani F, et al. Prevalence estimates for chronic diseases in Italy: exploring the differences between self-report and primary care databases. J Public Health Med. 2003;25(3):254–7.

Visentin E, Nieri D, Vagaggini B, Peruzzi E, Paggiaro P. An observation of prescription behaviors and adherence to guidelines in patients with COPD: real world data from October 2012 to September 2014. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;24:1–10.

Lawrenson R, Williams T, Farmer R. Clinical information for research; the use of general practice databases. J Public Health Med. 1999;21:299–304.

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Modifica alla Nota 13 di cui alla Determina del 26 marzo 2013. Gazzetta Ufficiale—Serie Generale, n. 156 del 08/07/2014.

Cicala S, de Simone G, Gerdts E, Dahlöf B, Lindholm LH, Kjeldsen SE, Devereux RB. Are coronary revascularization and myocardial infarction a homogeneous combined endpoint in hypertension trials? The Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:1134–40.

Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, Darius H, Lewis BS, Ophuis TO, Jukema JW, De Ferrari GM, Ruzyllo W, De Lucca P, Im K, Bohula EA, Reist C, Wiviott SD, Tershakovec AM, Musliner TA, Braunwald E. Califf RM; IMPROVE-IT investigators. ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2387–97.

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR. White HD; Writing Group on the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–67.

Di Carlo A, Inzitari D, Galati F, Baldereschi M, Giunta V, Grillo G, Furchi A, Manno V, Naso F, Vecchio A, Consoli D. A prospective community-based study of stroke in southern Italy: the Vibo Valentia incidence of Stroke Study (VISS): methodology, incidence and case fatality at 28 days, 3 and 12 months. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;16:410–7.

Colivicchi F, Bassi A, Santini M, Caltagirone C. Discontinuation of statin therapy and clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2007;38:2652–7.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification (CG 181). Clinical guideline, published: July 2014; updated: July 2016. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181. Accessed July 2016.

de Zeeuw D, Anzalone DA, Cain VA, Cressman MD, Heerspink HJ, Molitoris BA, Monyak JT, Parving HH, Remuzzi G, Sowers JR, Vidt DG. Renal effects of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin in patients with diabetes who have progressive renal disease (PLANET I): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:181–90.

Bhardwaj S, Selvarajah S, Schneider EB. Muscular effects of statins in the elderly female: a review. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:47–59.

Jones PH, Davidson MH, Stein EA, Bays HE, McKenney JM, Miller E, Cain VA, Blasetto JW, STELLAR Study Group. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of rosuvastatin versus atorvastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin across doses: STELLAR Trial. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:152–60.

Atar D, Carmena R, Clemmensen P, et al. Clinical review: impact of statin substitution policies on patient outcomes. Ann Med. 2009;41:242–56.

The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre. National Report on Medicines use in Italy. Year 2015. Rome: Italian Medicines Agency, 2016.

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016; 23:NP1–NP96.

Thomas M, Mann J. Increased thrombotic vascular events after change of statin. Lancet. 1998;352:1830–1.

Butler R, Wainwright J. Cholesterol lowering in patients with CHD and metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2007;369:27.

Phillips B, Aziz F, O’Regan CP, Roberts C, Rudolph AE, Morant S. Switching statins: the impact on patient outcomes. Br J Cardiol. 2007;14:280–5.

Acknowledgments

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by AstraZeneca SpA. Astrazeneca was not responsible for the study, data analysis, data interpretation, or construction of the manuscript. IMS Health Information Solutions Italy srl was responsible for data extraction, data analysis, medical writing and editorial assistance; this assistance was funded by AstraZeneca.

All authors were responsible for data interpretation and critically revised and approved the final manuscript. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Furio Colivicchi, Michele Massimo Gulizia, Laura Franzini, Giuseppe Imperoli, Lorenzo Castello, Alessandro Aiello, Claudio Ripellino, Nazarena Cataldo have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/41E6F0604FED8324.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Colivicchi, F., Gulizia, M.M., Franzini, L. et al. Clinical Implications of Switching Lipid Lowering Treatment from Rosuvastatin to Other Agents in Primary Care. Adv Ther 33, 2049–2058 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0412-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0412-8