Abstract

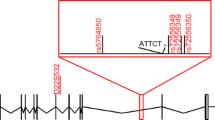

Relative frequency of hereditary ataxias remains unknown in many regions of Latin America. We described the relative frequency in spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA) due to (CAG)n and to (ATTCT)n expansions, as well as Friedreich ataxia (FRDA), among cases series of ataxic individuals from Peru. Among ataxic index cases from 104 families (38 of them with and 66 without autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance), we identified 22 SCA10, 8 SCA2, 3 SCA6, 2 SCA3, 2 SCA7, 1 SCA1, and 9 FRDA cases (or families). SCA10 was by far the most frequent one. Findings in SCA10 and FRDA families were of note. Affected genitors were not detected in 7 out of 22 SCA10 nuclear families; then overall maximal penetrance of SCA10 was estimated as 85%; in multiplex families, penetrance was 94%. Two out of nine FRDA cases carried only one allele with a GAA expansion. SCA10 was the most frequent hereditary ataxia in Peru. Our data suggested that ATTCT expansions at ATXN10 might not be fully penetrant and/or instability between generations might frequently cross the limits between non-penetrant and penetrant lengths. A unique distribution of inherited ataxias in Peru requires specific screening panels, considering SCA10 as first line of local diagnosis guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

15 January 2020

The original version of this article unfortunately contained some mistakes in Table 2. The additional row (just above SCA2) with the following information “SCA1, 1(1), 1, 50, 74, 24, 46 and 0/1” should be inserted.

References

Jayadev S, Bird TD. Hereditary ataxias: overview. Genet Med. 2013;15:673–83.

Bird TD. Hereditary ataxia overview. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, et al., editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1138/.

Sequeiros J, Martins S, Silveira I. Epidemiology and population genetics of degenerative ataxias. Handb Clin Neurol. 2012;103:227–51.

Durr A. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxias: polyglutamine expansions and beyond. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:885–94.

Gheno TC, Furtado GV, JAM S, Donis KC, AMV F, Emmel VE, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: common haplotype and disease progression rate in Peru and Brazil. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24:892–e36.

Campuzano V, Montermini L, Moltò MD, Pianese L, Cossée M, Cavalcanti F, et al. Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science. 1996;271:1423–7.

Bidichandani SI, Delatycki MB. Friedreich Ataxia. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, et al., editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1281/.

Hagerman P. Fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS): pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:1–19.

Ruano L, Melo C, Silva MC, Coutinho P. The global epidemiology of hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;42:174–83.

de Castilhos RM, Furtado GV, Gheno TC, Schaeffer P, Russo A, Barsottini O, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Brazil – frequencies and modulating effects of related genes. Cerebellum. 2014;13:17–28.

Molecular epidemiology of spinocerebellar ataxias in Cuba: insights into SCA2 founder effect in Holguin. - PubMed - NCBI [Internet]. [cited 2019 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19429075.

Alonso E, Martínez-Ruano L, De Biase I, Mader C, Ochoa A, Yescas P, et al. Distinct distribution of autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia in the Mexican population. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1050–3.

Teive HAG, Munhoz RP, Arruda WO, Raskin S, Werneck LC, Ashizawa T. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 – a review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011;17:655–61.

Paradisi I, Ikonomu V, Arias S. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Venezuela: genetic epidemiology and their most likely ethnic descent. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:215–22.

van de Warrenburg BPC, van Gaalen J, Boesch S, Burgunder J-M, Dürr A, Giunti P, et al. EFNS/ENS consensus on the diagnosis and management of chronic ataxias in adulthood. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:552–62.

Miller SA, Dykes DD, Polesky HF. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1215.

Cagnoli C, Michielotto C, Matsuura T, Ashizawa T, Margolis RL, Holmes SE, et al. Detection of large pathogenic expansions in FRDA1, SCA10, and SCA12 genes using a simple fluorescent repeat-primed PCR assay. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:96–100.

Harris DN, Song W, Shetty AC, Levano KS, Cáceres O, Padilla C, et al. Evolutionary genomic dynamics of Peruvians before, during, and after the Inca empire. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E6526–35.

Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo de Pueblos Andinos, Amazónicos y Afroperuanos (INDEPA). Ethnolinguistic map of Peru. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2010;27:288–91.

Cintra VP, Lourenço CM, Marques SE, de Oliveira LM, Tumas V, Marques W. Mutational screening of 320 Brazilian patients with autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 2014;347:375–9.

Teive HAG, Munhoz RP, Raskin S, Arruda WO, de Paola L, Werneck LC, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: frequency of epilepsy in a large sample of Brazilian patients. Mov Disord. 2010;25:2875–8.

Cornejo-Olivas M, Cornejo-Herrera I, Lindo-Samanamud S, Castilhos R, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Jardim L, et al. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 10 or SCA10 in Peruvian Population. First Report of Three Families (IN6–1.007). Neurology [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Mar 7];80:IN6–1.007-IN6–1.007. Available from: https://n.neurology.org/content/80/7_Supplement/IN6-1.007.

Wang K, McFarland KN, Liu J, Zeng D, Landrian I, Xia G, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 in Chinese Han. Neurol Genet. 2015;1:e26.

Naito H, Takahashi T, Kamada M, Morino H, Yoshino H, Hattori N, et al. First report of a Japanese family with spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: the second report from Asia after a report from China. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177955.

Bampi GB, Bisso-Machado R, Hünemeier T, Gheno TC, Furtado GV, Veliz-Otani D, et al. Haplotype study in SCA10 families provides further evidence for a common ancestral origin of the mutation. NeuroMolecular Med. 2017;19:501–9.

Schmitz-Hübsch T, du Montcel ST, Baliko L, Berciano J, Boesch S, Depondt C, et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: development of a new clinical scale. Neurology. 2006;66:1717–20.

Kieling C, Rieder CRM, Silva ACF, JAM S, Cecchin CR, Monte TL, et al. A neurological examination score for the assessment of spinocerebellar ataxia 3 (SCA3). Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:371–6.

Matsuura T, Fang P, Pearson CE, Jayakar P, Ashizawa T, Roa BB, et al. Interruptions in the expanded ATTCT repeat of spinocerebellar ataxia type 10: repeat purity as a disease modifier? Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:125–9.

Alonso I, Jardim LB, Artigalas O, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Matsuura T, Ashizawa T, et al. Reduced penetrance of intermediate size alleles in spinocerebellar ataxia type 10. Neurology. 2006;66:1602–4.

Gatto EM, Gao R, White MC, Uribe Roca MC, Etcheverry JL, Persi G, et al. Ethnic origin and extrapyramidal signs in an Argentinean spinocerebellar ataxia type 10 family. Neurology. 2007;69:216–8.

Schüle B, McFarland KN, Lee K, Tsai Y-C, Nguyen K-D, Sun C, et al. Parkinson’s disease associated with pure ATXN10 repeat expansion. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2017;3:27.

Jonker MA, Rijken JA, Hes FJ, Putter H, Hensen EF. Estimating the penetrance of pathogenic gene variants in families with missing pedigree information. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;962280218791338.

Galea CA, Huq A, Lockhart PJ, Tai G, Corben LA, Yiu EM, et al. Compound heterozygous FXN mutations and clinical outcome in Friedreich ataxia. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:485–95.

Fussiger H, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Leistner-Segal S, Jardim LB. Friedreich Ataxia: diagnostic yield and minimal frequency in South Brazil. Cerebellum. 2019;18:147–51.

Pujana MA, Corral J, Gratacòs M, Combarros O, Berciano J, Genís D, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in Spanish patients: genetic analysis of familial and sporadic cases. The Ataxia Study Group. Hum Genet. 1999;104:516–22.

Jardim LB, Silveira I, Pereira ML, Ferro A, Alonso I, do Céu Moreira M, et al. A survey of spinocerebellar ataxia in South Brazil – 66 new cases with Machado-Joseph disease, SCA7, SCA8, or unidentified disease-causing mutations. J Neurol. 2001;248:870–6.

Maruyama H, Izumi Y, Morino H, Oda M, Toji H, Nakamura S, et al. Difference in disease-free survival curve and regional distribution according to subtype of spinocerebellar ataxia: a study of 1,286 Japanese patients. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:578–83.

Wang J, Shen L, Lei L, Xu Q, Zhou J, Liu Y, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxias in mainland China: an updated genetic analysis among a large cohort of familial and sporadic cases. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2011;36:482–9.

Koutsis G, Pemble S, Sweeney MG, Paudel R, Wood NW, Panas M, et al. Analysis of spinocerebellar ataxias due to expanded triplet repeats in Greek patients with cerebellar ataxia. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:178–80.

Shimazaki H, Takiyama Y, Sakoe K, Amaike M, Nagaki H, Namekawa M, et al. Meiotic instability of the CAG repeats in the SCA6/CACNA1A gene in two Japanese SCA6 families. J Neurol Sci. 2001;185:101–7.

Laffita-Mesa JM, Rodríguez Pupo JM, Moreno Sera R, Vázquez Mojena Y, Kourí V, Laguna-Salvia L, et al. De novo mutations in ataxin-2 gene and ALS risk. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70560.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank patients and families affected from inherited ataxias that kindly contributed to research on ataxias in Peruvian population. We would also thank Diego Veliz-Otani for critical review of the manuscript. We are grateful to RIBERMOV “Red Iberoamericana Multidisciplinar para el Estudio de los Trastornos de Movimiento” for providing the initial environment for collaborative research studies, as this one, among Latin Americans.

Funding

EPM, GVF, GBB, SLS, MLSP, and LBJ were supported by the National Council for Research and Development (CNPq), Brazil. LBJ received grants from Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (FIPE 2006-0384) and Pesquisa para o SUS/Fundo de Apoio à Pesquisa do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (PPSUS-FAPERGS, PROCESS 07-00832), for performing the laboratory procedures. MCO, MIM, VM, and PM are partially supported by research funds provided by Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Neurológicas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article was revised: The additional row (just above SCA2) with the following information “SCA1, 1(1), 1, 50, 74, 24, 46 and 0/1” were inserted.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 1544 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cornejo-Olivas, M., Inca-Martinez, M., Castilhos, R.M. et al. Genetic Analysis of Hereditary Ataxias in Peru Identifies SCA10 Families with Incomplete Penetrance. Cerebellum 19, 208–215 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01098-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-019-01098-2