Abstract

Follicular peripheral T-cell lymphoma (F-PTCL) is a newly recognized provisional entity in the 2017 World Health Organization Classification revision of hematolymphoid neoplasms. It is a rare and under-recognized manifestation of peripheral T-cell lymphoma that is associated with a typically aggressive clinical course. Cases feature a predominantly follicular or perifollicular growth pattern and exhibit strong and consistent expression of T-follicular helper (TFH) markers. These cases distinctly lack histologic features commonly associated with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, such as an associated polymorphous infiltrate, proliferation of high endothelial venules or expanded follicular dendritic meshworks. A relatively specific t(5;9)(q33;q22) rearrangement, leading to ITK-SYK fusion is seen in about 20% of cases. Herein, we summarize key features of F-PTCL and briefly review the evolving relationship to other nodal T-cell lymphomas/lymphoproliferative disorders of TFH-derivation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The most recent World Health Organization (WHO) classification of hematolymphoid neoplasms includes a new category of “Nodal lymphomas of T-follicular helper cell origin” [1]. Within this new category are angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and two additional provisional entities: follicular peripheral T-cell lymphoma (F-PTCL) and nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a T-follicular helper phenotype (PTCL-TFH). Part of the justification for this new classification includes evidence that some cases of PTCL-NOS are associated with an underlying TFH-related molecular signature and/or express a TFH-immunophenotype [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Interestingly, approximately 20–25% of PTCL-NOS have been described to harbor a TFH gene signature [2,3,4]. Immunohistochemical TFH-associated markers include CD10, BCL6, CXCL13, PD-1 and ICOS, although less commonly available markers may also include SAP, CCR5, c-MAF and CD200 [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These markers vary in their respective sensitivity and specificities; therefore, a neoplasm suspected to be derived from T-follicular helper (TFH) cells, the WHO currently recommends demonstration of expression of a minimum of at least two (preferably three) markers. While AITL remains the most-studied example of a TFH-derived neoplasm and shares many clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic and genetic findings with that of F-PTCL, notable differences exist. In this review, we focus on defining the evolving characteristics of F-PTCL and discuss the differential diagnosis, particularly as it relates to AITL and PTCL-TFH.

Clinical features

F-PTCL is one of the rarest subtypes of mature T-cell lymphomas, representing only 1–2% of cases by the current WHO classification [18]. Cases typically occur in the elderly with a slight male predominance [7, 19]. B-symptoms are reported in approximately one-third of cases [7, 19, 20]. Disseminated/advanced stage nodal disease is a typical presentation with occasional hepatosplenomegaly or cutaneous involvement similar to PTCL-NOS. Bone marrow involvement involves approximately 26% of cases [19]. Laboratory findings of a positive Coombs test and/or hypergammaglobulinemia, findings typically associated with AITL can occasionally be seen in FTCL [7, 19, 21].

Histopathology

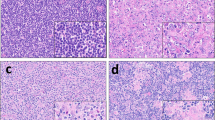

Two main architectural patterns have been described, which include a much more common progressive transformation of germinal center-like pattern and a less common nodular/follicular growth pattern. These architectures loosely approximate more familiar patterns, mainly as the names imply progressive transformation of the germinal centers and classic follicular lymphoma, respectively. Of note, these architectures are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as mixed patterns have also been reported. The progressive transformation of germinal center-like nodules are comprised of mature appearing B-lymphocytes that are IgD-positive admixed with dispersed small aggregates of neoplastic cells (Fig. 1). While, in the follicular pattern, the neoplastic cells are confined exclusively within lymphoid follicles often with attenuated mantle zones. The neoplastic infiltrate typically features a monotonous lymphoid infiltrate exhibiting vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, abundant pale/clear cytoplasm and only mild atypia. Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg (HRS)-like cells and/or epithelioid histiocytes are both seen in most cases [22,23,24,25]. In addition, F-PTCL lack florid hyperplasia of high-endothelial venules (HEV) or a polymorphous cellular infiltrate, including eosinophils and/or plasma cells.

Progressive transformation of germinal center-like pattern of follicular peripheral T-cell lymphoma demonstrates partial effacement of architecture by a nodular proliferation of lymphocytes with expanded mantle zones and regressed germinal centers (a—H&E 2x) (b—H&E 4x). Inset: One neoplastic nodule is featured composed of medium-sized cells with round to oval nuclear contours and ample clear cytoplasm, enclosed by small mature-appearing lymphoid cells (c—H&E, 40x)

By immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2), the neoplastic cells exhibit a T-cell phenotype including CD2 + , CD3 + , CD5 + with common loss of CD7. A helper T-cell phenotype CD4 + CD8- is typical, albeit uncommon CD4(-) CD8(-) cases have been described [7, 23]. Importantly, follicular dendritic cells, highlighted by either CD21, CD23 and/or CD35 remain largely intact within remnant follicles, without evidence for expansion or arborization typical features seen in cases of AITL. CD21 and CD23 may dimly highlight mature B cells associated with areas of progressive transformation of germinal center-like pattern. A TFH-immunophenotype is demonstrated by almost all cases showing positivity for PD-1 or ICOS and most cases positive for CD10, BCL6 and/or CXCL13 [5, 7, 19, 24, 25] (Fig. 3). MUM-1/IRF4 can be positive in some cases. TIA-1 and granzyme-B are negative. As previously mentioned HRS-like cells, which are seen in the majority of cases feature both CD30 and IRF4/MUM1 positivity with expression of PAX5. CD30 expression by the neoplastic T-cell infiltrate occurs with some frequency (up to 75% of cases), which often is variable in intensity, but typically dimmer than that of HRS-like cells [22]. CD20 immunostaining is negative in the T-cell infiltrate, but may help highlight a, “moth-eaten” architecture with negative staining of the T-cell infiltrate. EBV (LMP-1 and/or EBER-ISH) can be demonstrated involving activated B-cells or (HRS)-like cells in a significant portion of studied cases [22, 23, 26, 27]. Ki-67 staining for proliferation is variable with a median value of 45% [23]. The pattern of bone marrow involvement has been described as interstitial and/or paratrabecular [28, 29].

CD4 expression is appreciated in lymphomatous nodules (a – 10x). CD3 immunostain highlights both neoplastic cells and background small mature T-cells (b – 4x). Scattered background T-cells exhibit CD8 expression with absence of labeling of neoplastic cells (c – 10x). CD20 immunostain labels germinal centers and expanded mantle zones (d – 4x). Weak to moderate CD30 expression is seen in neoplastic cell clusters (e – 40x). CD21 demonstrates follicular dendritic cell meshworks with weak staining of mantle zones and negative expression of neoplastic elements in parafollicular zone (f – 10x)

Ancillary studies

A monoclonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor genes is seen in 85–100% of cases [19, 28]. Reports vary in respect to frequency of a clonal immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement, some report 25% of cases, while another review found no evidence of monoclonal IgH gene rearrangements [19, 28]. Positive monoclonal IgH gene rearrangements are an interesting finding as they have been frequently described in cases of AITL [29,30,31]. Conventional cytogenetic studies involving F-PTCL frequently reveal an abnormal, usually complex karyotype [19]. Fluorescent in-situ hybridization studies have demonstrated recurrent translocations of ITK gene on chromosome 5q33 and SYK gene on 9q22 which result in an ITK-SYK fusion transcript in approximately 20% of cases [32]. This translocation has only been reported in a single case of AITL [33].

The mutational status of PTCL-TFH and F-PTCL remain considerably less explored when compared to the more studied counterpart AITL. Although, a recent clinicopathological and molecular analysis by Dobay et al. compared AITL and other nodal PTCLs of TFH origin [10]. They report F-PTCL harbors molecular mutational findings involving TET-2 (3/4 cases), DNMT3A (1/4 cases), and RHOA (G17V) (3/5 cases), with no cases showing IDH2 mutation (0/5 cases). AITL and PTCL-TFH harbored these mutations at similar frequencies with exception of IDH2, being more or less restricted to AITL. They also reported remarkable overlap by gene expression profiling for AITL, F-PTCL and TFH-like PTCLs in both global and specific gene expression patterns. RHOA gene mutations, most commonly involving a substitution of valine for glycine at residue 17 (p.Gly17Val), particularly appear to be associated with significantly higher likelihood of immunohistochemical positivity for two or more TFH markers and a trend toward some AITL clinicopathological characteristics [34].

Differential diagnosis

The histopathologic features of F-PTCL requires careful morphologic and immunohistochemical evaluation, as separation between other T-cell neoplasms including AITL and PTCL-NOS can be difficult. This is highlighted in part due to the neoplastic infiltrate in these entities may show similar if not identical cytologic findings of small to medium-sized cells with only minimal to mild atypia. Although, the histologic examination can generally exclude non-lymphoid neoplasms, the separation of reactive etiologies can also be problematic. HRS-like cells can be seen across the spectrum of nodal lymphomas of TFH-cell origin and could be misdiagnosed as either classical Hodgkin lymphoma or nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. Careful detail to architectural and cytological atypia and an aberrant T-cell immunophenotype are crucial for an accurate diagnosis. Of note, TFH marker expression among a particular T-cell population in isolation is not necessarily indicative of T-cell malignancy, as it has been shown that TFH expansion can occur in reactive as well as other neoplastic proliferations [35, 36] . Careful assessment for T-cell clonality in some cases may be helpful to further determine a neoplastic etiology.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

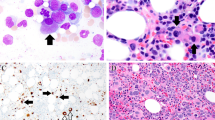

The prototypic TFH-derived neoplasm is AITL, which has undergone numerous historical revisions, but the current definition outlines a neoplasm derived from TFH-cells and further characterized as a systemic disease associated with a histological polymorphous infiltrate usually associated with florid proliferation of HEVs and enlarged follicular dendritic cell meshworks [1] (Fig. 4). AITL has been further characterized as having three distinct histologic nodal patterns [12, 37]. Pattern 1 (20% of cases) is characterized by intact nodal architecture associated with hyperplastic germinal centers frequently surrounded at the margins by neoplastic T-cells. Only a modest expansion of the paracortex is noted, which typically features a polymorphic infiltrate of lymphocytes, transformed lymphoid blasts, plasma cells, eosinophils, macrophages and with or without HRS-like cells within a conspicuously vascular network. Pattern 2 (30% of cases) is characterized by loss of nodal architecture, aside from only occasional retainment of often depleted/atretic appearing follicles associated with concentrically arranged follicular dendritic cells as well as a more robust polymorphous infiltrate extending beyond just the paracortex. Pattern 3 (50% of cases) is defined as overt nodal effacement without any remnant B-cell follicles. It has been suggested that these patterns may correlate with tumor progression with pattern III representing the most advanced disease for AITL [12, 37,38,39]. Patterns 1–2 of AITL particularly can be troublesome to distinguish F-PTCL as both can exhibit similar architecture and cytologic features. The most notable aspects to distinguish these entities involve F-PTCL showing lack of an associated polymorphous infiltrate, proliferation of high endothelial venules or evidence of an expanded follicular dendritic meshwork. Activated B-cells or HRS-like cells can be seen in both AITL and F-PTCL and should not be used to further differentiate.

Typical appearance of AITL, featuring a complete architecture effacement by a neoplastic population of lymphoid cells with pale to clear cytoplasm, accompanied by proliferation of vessels in a polymorphous background (a–b; 4 × and 20x, respectively). Expanded follicular dendritic meshworks, CD21 immunostain (c – 2x). CD4 versus CD8 immunostains, demonstrate predominantly CD4 + population (d–e, respectively; 2x). Neoplastic cells exhibiting positive labeling for PD-1 immunostain (f – 40x)

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a T-follicular helper phenotype

PTCL-TFH are generally characterized as a diffuse neoplastic proliferation as opposed to the nodular/follicular or progressive transformation of germinal center-like architecture associated with F-PTCL. Similar to F-PTCL a prominent polymorphic background, marked vascular proliferation, or expansion of follicular dendritic cell meshworks are not typical findings for PTCL-TFH. Of note, upwards of 41% of PTCL-NOS cases can potentially be reclassified to PTCL-TFH based on immunohistochemical expression ≥ 2 TFH markers [40].

Hodgkin lymphoma

The presence of activated B-cells or HRS-like cells can be seen across the spectrum of nodal lymphomas of TFH-cell origin [22, 23, 41]. Therefore, the differential diagnosis commonly includes classical Hodgkin lymphoma and/or nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (Fig. 5). As previously mentioned, the presence of HRS-like cells is not an infrequent finding and in fact has been reported in most F-PTCL cases [22]. These HRS-like cells frequently express CD30 and are EBV-positive, with less frequent expression of CD20 and/or CD15. In fact, the immunophenotype of the HRS-like cells in F-PTCL has even been shown to so closely approximate classical Hodgkin lymphoma that it is not recommended to differentiate these entities. In addition, rosetting T-cells around HRS (-like) cells has been noted to be a common finding in follicular T-cell lymphoma as well as classical and nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphomas. It has, therefore, been proposed that the assessment of the neoplastic T-cell population for expression of CD10, CD30 and/or the presence of a T-cell clone represent more reliable elements to suggest F-PTCL.

An example of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, exhibiting a typical nodular architectural pattern with areas of progressive transformation (a – 4x). The nodules demonstrate scattered LP cells in the background of abundant mature lymphocytes and histiocytes (b – 40x). Both expanded and intact germinal centers highlighted by CD23 immunostain (c – 40x)

Follicular lymphoma

F-PTCL, as the name implies, could be confused with follicular lymphoma, particularly featuring exclusively a follicular/nodular pattern at low magnification (Fig. 6). In addition, features that are well described in follicular lymphoma, such as partial effacement of architecture by poorly defined disorganized/non-polarized follicles with attenuated or absent mantle zones, infrequent mitotic activity and lack of tangible body macrophages are findings that can accompany F-PTCL. In addition, immunohistochemical staining may reveal that the neoplastic cells express BCL-6, BCL-2 and/or CD10 positivity. Histology favoring a diagnosis of F-PTCL would include cytologic features of a monotonous lymphoid infiltrate with abundant pale/clear cytoplasm and only mild atypia with notable absence of centrocytic/centroblastic morphology. Immunohistochemical staining for evidence of a T-cell CD4 + predominating infiltrate within follicles as well as evidence of a TFH immunophenotype including CXCL13, PD-1 and/or ICOS would exclude follicular lymphoma.

Follicular lymphoma, low grade, demonstrating typical back-to-back follicles with attenuated mantle zones (a – 2x), composed mostly by centrocytes with occasional scattered centroblasts (b – 100x), which demonstrate strong labeling for CD10 (c – 10x), CD20 (d – 4x) with no expression of CD3 (e – 4x). CD21 immunostain highlights follicular dendritic meshworks confined to the follicles (f – 10x)

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders/lymphomas

Primary cutaneous CD4 + small/medium lymphoproliferative disorder (PCSM-LPD) is characterized as a solitary cutaneous lesion mostly located around the head and neck region without clinical evidence of patches or plaques that are typical of mycosis fungoides [1]. Histologically, it features a dense, pleomorphic T-cell infiltrate within the dermis classically associated with a rich inflammatory background of B-cells, plasma cells and/or histiocytes. Epidermotropism is not a typical finding. The pleomorphic T-cell infiltrate commonly expresses TFH-markers including BCL6, PD1 and CXCL13, although CD10 appears to be a less common finding [1, 42]. EBV is invariably negative. F-PTCL cutaneous involvement has been reported [7, 19, 43], which in contrast to primary cutaneous CD4 + small/medium lymphoproliferative disorder, CD10 + is typically positive and follicular dendritic meshworks are frequently present. CD30 is often negative in PCSM-LPD, but increased expression has been reported, albeit rarely exceeding 30% [44]. Distinguishing cutaneous lesions exclusively on a histologic basis between F-PTCL and other entities such as PCSM-LPD may be difficult and correlation with the presence of systemic features, lymphadenopathy and clinical course may be necessary to further differentiate. It should also be noted that a TFH immunophenotype has also been described in cutaneous neoplasms including mycosis fungoides and Sezary Syndrome [45].

Treatment and prognosis

Comprehensive data regarding the clinical course and prognosis of F-PTCL is lacking, but of the reported cases, there is considerable variability with occasional descriptions noting an indolent/protracted often localized presentation, while an aggressive course similar to AITL appears to be more common [7, 19, 22]. Currently, the diagnosis of F-PTCL as opposed to PTCL-NOS has little to no impact on clinical management, although targeted therapy based on mutational status, including hypomethylating agents remain therapeutic possibilities [46, 47].

Conclusion

The origin and relationship of F-PTCL to AITL and PTCL-NOS have been of considerable debate and controversy to the precise diagnostic borders and minimal criterion to establish an accurate diagnosis. Historically, the first descriptions of peripheral T-cell lymphomas associated with a predominating nodular/follicular architecture were first reported in 1988 [48]. It was then later recognized that these neoplasms often exhibit distinct immunophenotypic findings and was first hypothesized by de Leval et al. that perhaps these represent derivation from T follicular helper cells [49]. Subsequently, the 2008 WHO classification of hematopoietic neoplasms defined F-PTCL as a variant of PTCL-NOS, in contrast to the current classification as previously mentioned in the 2017 revision as a subtype of, “Nodal lymphomas of TFH-cell origin”. Currently, it remains to be determined if F-PTCL is best characterized as a distinct entity or if perhaps a different histologic depiction on a continuum of a single biological process. Further complicating precise categorization of F-PTCL, as it not only shares some similar underlying molecular findings and immunophenotype to other nodal lymphomas of T-follicular helper cell origin, but on occasion, patients may even switch histology from AITL or F-PTCL over the course of their disease [7, 22]. In conclusion, F-PTCL is an aggressive TFH-derived neoplasm with a t(5;9)(q33;q22) ITK-SYK rearrangement seen in about 20% of cases. Histologically, it is characterized by exhibiting a follicular or perifollicular growth pattern with distinct lack of histologic features commonly associated with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma including an associated polymorphous infiltrate, proliferation of HEVs or expanded follicular dendritic meshworks.

Data and materials availability

All data and materials as well as software application or custom code support their published claims and comply with field standards.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J, (Eds.) (2017) WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, Revised 4th ed.; IARC: Lyon, France

De leval L, Rickman DS, Thielen C et al (2007) The gene expression profile of nodal peripheral T-cell lymphoma demonstrates a molecular link between angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL) and follicular helper T (TFH) cells. Blood 109(11):4952–4963

Piccaluga PP, Agostinelli C, Califano A et al (2007) Gene expression analysis of angioimmunoblastic lymphoma indicates derivation from T follicular helper cells and vascular endothelial growth factor deregulation. Cancer Res 67(22):10703–10710

Iqbal J, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC et al (2010) Molecular signatures to improve diagnosis in peripheral T-cell lymphoma and prognostication in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood 115(5):1026–1036

Agostinelli C, Hartmann S, Klapper W et al (2011) Peripheral T cell lymphomas with follicular T helper phenotype: a new basket or a distinct entity? Revising Karl Lennert’s personal archive. Histopathology 59(4):679–691

Pileri SA (2015) Follicular helper T-cell-related lymphomas. Blood 126(15):1733–1734

Huang Y, Moreau A, Dupuis J et al (2009) Peripheral T-cell lymphomas with a follicular growth pattern are derived from follicular helper T cells (TFH) and may show overlapping features with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 33(5):682–690

Lemonnier F, Couronné L, Parrens M et al (2012) Recurrent TET2 mutations in peripheral T-cell lymphomas correlate with TFH-like features and adverse clinical parameters. Blood 120(7):1466–1469

Palomero T, Couronné L, Khiabanian H et al (2014) Recurrent mutations in epigenetic regulators, RHOA and FYN kinase in peripheral T cell lymphomas. Nat Genet 46(2):166–170

Dobay MP, Lemonnier F, Missiaglia E et al (2017) Integrative clinicopathological and molecular analyses of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and other nodal lymphomas of follicular helper T-cell origin. Haematologica 102(4):e148–e151

Marafioti T, Paterson JC, Ballabio E et al (2010) The inducible T-cell co-stimulator molecule is expressed on subsets of T cells and is a new marker of lymphomas of T follicular helper cell-derivation. Haematologica 95(3):432–439

Attygalle A, Al-jehani R, Diss TC et al (2002) Neoplastic T cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma express CD10. Blood 99(2):627–633

Dorfman DM, Shahsafaei A (2011) CD200 (OX-2 membrane glycoprotein) is expressed by follicular T helper cells and in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 35(1):76–83

Dupuis J, Boye K, Martin N et al (2006) Expression of CXCL13 by neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL): a new diagnostic marker providing evidence that AITL derives from follicular helper T cells. Am J Surg Pathol 30(4):490–494

Krenacs L, Schaerli P, Kis G, Bagdi E (2006) Phenotype of neoplastic cells in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma is consistent with activated follicular B helper T cells. Blood 108(3):1110–1111

Roncador G, Garcíaverdes-montenegro JF, Tedoldi S et al (2007) Expression of two markers of germinal center T cells (SAP and PD-1) in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Haematologica 92(8):1059–1066

Rodríguez-pinilla SM, Atienza L, Murillo C et al (2008) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with follicular T-cell markers. Am J Surg Pathol 32(12):1787–1799

Weisenburger DD, Savage KJ, Harris NL et al (2011) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified: a report of 340 cases from the International Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma Project. Blood 117(12):3402–3408

Hu S, Young KH, Konoplev SN, Medeiros LJ (2012) Follicular T-cell lymphoma: a member of an emerging family of follicular helper T-cell derived T-cell lymphomas. Hum Pathol 43(11):1789–1798

Macon WR, Williams ME, Greer JP, Cousar JB (1995) Paracortical nodular T-cell lymphoma. Identification of an unusual variant of peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 19(3):297–303

Federico M, Rudiger T, Bellei M et al (2013) Clinicopathologic characteristics of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: analysis of the international peripheral T-cell lymphoma project. J Clin Oncol 31(2):240–246

Hartmann S, Goncharova O, Portyanko A et al (2019) CD30 expression in neoplastic T cells of follicular T cell lymphoma is a helpful diagnostic tool in the differential diagnosis of Hodgkin lymphoma. Mod Pathol 32(1):37–47

Moroch J, Copie-bergman C, De leval L et al (2012) (2012) Follicular peripheral T-cell lymphoma expands the spectrum of classical Hodgkin lymphoma mimics. Am J Surg Pathol. 36(11):1636–1646

Bacon CM, Paterson JC, Liu H et al (2008) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a follicular growth pattern: derivation from follicular helper T cells and relationship to angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 143:439–441

Goto N, Tsurumi H, Sawada M et al (2011) Follicular variant of peripheral T-cell lymphoma mimicking follicular lymphoma: a case report with a review of the literature. Pathol Int 61:326–330

Mathas S, Hartmann S, Küppers R (2016) Hodgkin lymphoma: pathology and biology. Semin Hematol 53(3):139–147

Miyoshi H, Sato K, Niino D et al (2012) Clinicopathologic analysis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma, follicular variant, and comparison with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma: Bcl-6 expression might affect progression between these disorders. Am J Clin Pathol 137(6):879–889

Ikonomou IM, Tierens A, Troen G et al (2006) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with involvement of the expanded mantle zone. Virchows Arch 449(1):78–87

Ortiz-Muchotrigo N, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Ramos R et al (2009) Follicular T-cell lymphoma: description of a case with characteristic findings suggesting it is a different condition from AITL. Histopathology 54(7):902–904

Zaki MA, Wada N, Kohara M et al (2011) Presence of B-cell clones in T-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol 86(5):412–419

Tan BT, Warnke RA, Arber DA (2006) The frequency of B- and T-cell gene rearrangements and epstein-barr virus in T-cell lymphomas: a comparison between angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified with and without associated B-cell proliferations. J Mol Diagn 8(4):466–475

Streubel B, Vinatzer U, Willheim M, Raderer M, Chott A (2006) Novel t(5;9)(q33;q22) fuses ITK to SYK in unspecified peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia 20(2):313–318

Attygalle AD, Feldman AL, Dogan A (2013) ITK/SYK translocation in angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol 37(9):1456–1457

Miyoshi H, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Shimono J et al (2020) RHOA mutation in follicular T-cell lymphoma: clinicopathological analysis of 16 cases. Pathol Int 70(9):653–660

Egan C, Laurent C, Alejo JC et al (2020) Expansion of pd1-positive t cells in nodal marginal zone lymphoma: a potential diagnostic pitfall. Am J Surg Pathol 44(5):657–664

Abukhiran I, Syrbu SI, Holman CJ (2021) Markers of follicular helper T cells are occasionally expressed in T-cell or histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma, classic hodgkin lymphoma, and atypical paracortical hyperplasiaA diagnostic pitfall for T-cell lymphomas of T follicular helper origin. Am J Clin Pathol 156(3):409–426

Ree HJ, Kadin ME, Kikuchi M et al (1998) Angioimmunoblastic lymphoma (AILD-type T-cell lymphoma) with hyperplastic germinal centers. Am J Surg Pathol 22(6):643–655

Dogan A, Attygalle AD, Kyriakou C (2003) Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. (Review). Br J Haematol 121:681–691

Attygalle AD, Kyriakou C, Dupuis J et al (2007) Histologic evolution of angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma in consecutive biopsies: clinical correlation and insights into natural history and disease progression. Am J Surg Pathol 31(7):1077–1088

Basha BM, Bryant SC, Rech KL et al (2019) Application of a 5 marker panel to the routine diagnosis of peripheral T-cell lymphoma with T-follicular helper phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 43(9):1282–1290

Nicolae A, Pittaluga S, Venkataraman G, Vijnovich-Baron A, Xi L, Raffeld M et al (2013) Peripheral T-cell lymphomas of follicular T-helper cell derivation with Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells of B-cell lineage: both EBV-positive and EBV-negative variants exist. Am J Surg Pathol 37:816–826

Gru AA, Wick MR, Eid M (2018) Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder-clinical and histopathologic features, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Cutan Med Surg 37(1):39–48

Le tourneau A, Audouin J, Molina T, et al (2010) Primary cutaneous follicular variant of peripheral T-cell lymphoma NOS. A report of two cases. Histopathology 56(4):548–551

Magro CM, Olson LC, Fulmer CG (2017) CD30+ T cell enriched primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium sized pleomorphic T cell lymphoma: a distinct variant of indolent CD4+ T cell lymphoproliferative disease. Ann Diagn Pathol 30:52–58

Meyerson HJ, Awadallah A, Pavlidakey P, Cooper K, Honda K, Miedler J (2013) Follicular center helper T-cell (TFH) marker positive mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. Mod Pathol 26(1):32–43

Cheminant M, Bruneau J, Kosmider O et al (2015) Efficacy of 5-azacytidine in a TET2 mutated angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 168(6):913–916

Lemonnier F, Dupuis J, Sujobert P et al (2018) Treatment with 5-azacytidine induces a sustained response in patients with angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Blood 132(21):2305–2309

van den Oord JJ, de Wolf-Peeters C, O’Connor NT, de Vos R, Tricot G, Desmet VJ (1988) Nodular T-cell lymphoma. Report of a case studied with morphologic, immunohistochemical, and DNA hybridization techniques. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 112(2):133–138

de Leval L, Savilo E, Longtine J, Ferry JA, Harris NL (2001) Peripheral T-cell lymphoma with follicular involvement and a CD4+/bcl-6+ phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 25(3):395–400

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Given the retrospective nature and absence of protected health information, IRB approval was not sought.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramos, J., Ward, N. Follicular T-cell lymphoma: a short review with brief discussion of other nodal lymphomas/lymphoproliferative disorders of T-follicular helper cell origin. J Hematopathol 14, 261–268 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-021-00460-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-021-00460-w