Abstract

Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffolds (BVS) manufactured from poly (l-lactic acid) (PLLA) offer an alternative to metal scaffolds for the treatment of coronary heart disease. One of the key steps in the manufacture of these scaffolds is the stretch blow moulding process where the PLLA is biaxially stretched above glass transition temperature (Tg), inducing biaxial orientation and thus increasing ductility, strength and stiffness. To optimise the manufacture and performance of these scaffolds it is important to understand the influence of temperature and strain rate on the constitutive behaviour of PLLA in the blow moulding process. Experiments have been performed on samples of PLLA on a custom built biaxial stretch testing machine to replicate conditions typically experienced during blow moulding i.e. in a temperature range from 70 °C to 100 °C and at strain rates of 1 s−1, 4 s−1 and 16 s−1 respectively. The data is subsequently used to calibrate a nonlinear viscoelastic material model to represent the deformation behaviour of PLLA in the blow moulding process. The results highlight the significance of temperature and strain rate on the yielding and strain hardening behaviour of PLLA and the ability of the selected model to capture it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

PLLA is a bioresorbable polymer used widely in the medical device industry. One such medical device is a bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS) which is used for the treatment of coronary heart disease. These scaffolds have the potential to replace metal scaffolds (stents) since they have the advantage of supporting the artery for 6 months and of being completely resorbed into the body within 2 years, thus preventing late stent thrombosis and in stent restenosis [1, 2]. Un-oriented PLLA in its natural format is typically a brittle material that does not have the desired mechanical properties to resist the forces experienced during crimping and deployment [3,4,5]. To further enhance its mechanical performance, a change of molecular orientation and crystallinity can be induced by performing biaxial stretching at temperatures above the glass transition temperature (Tg). As a result, stretch blow moulding was introduced as a process to manufacture BVS with the desired mechanical properties [6]. As shown in Fig. 1, in the manufacture of BVS from PLLA via stretch blow moulding [6, 7], a PLLA tube is placed in a closed mould, where the material temperature is gradually increased to above Tg, so that the material achieves a rubbery state. The tube is inflated by applying pressure to align the molecular chains circumferentially whilst the end of tube is simultaneously or sequentially stretched to introduce biaxial orientation of molecular chains.

BVS manufactured by stretch blow moulding have shown significant enhancement of the fracture strength and toughness [3, 8]. In the case of cast PLLA sheets at temperatures ranging from 60 °C to 100 °C showed an increase in elastic modulus and tensile strength of 58.4% and 77.4% respectively following biaxial orientation [9]. These mechanical properties also exhibit dependence on the induced stretch ratio and the temperature of stretch. In another study by Zenkiewicz [10], the effects of blow-up ratio of blow moulding were investigated and a value of 4.0 was recommended to improve the elastic modulus, tensile strength and tensile stress at break. A study on PLLA tubes manufactured via stretch blow moulding [11] demonstrated that the ultimate strength and elongation at break of PLLA tubes after forming are strongly related to the degree of hoop expansion, axial elongation and forming sequence. The data produced from both simultaneous and sequential biaxial stretch showed that the tensile strength increased with higher stretch ratios. The cited work highlights that the process conditions applied in stretch blow moulding strongly influence the mechanical properties of the manufactured products.

The mechanical behaviour of polymer materials above Tg is significantly correlated with the thermal processing conditions. Several authors have previously investigated the uniaxial and biaxial properties of PLLA materials in the processing range of temperatures i.e. between the glass transition temperature (~65 °C) and the cold crystallization temperature (~100 °C). In a biaxial orientation study on PLLA by Chapleau et al. [9], stress vs biaxial drawing ratios curves for three processing temperatures (70 °C, 80 °C and 90 °C) at a strain rate of 0.33 s−1 highlighted significant temperature dependence of the mechanical behaviour. Higher stresses were developed for materials stretched to the same stretch ratios with decreasing temperatures and different maximum biaxial drawing ratios can be reached before failure at different temperatures, e.g. PLLA can be biaxially stretched to 6 × 6 at 90 °C while the maximum biaxial draw ratio at 70 °C was just above 3 × 3. Stoclet et al. [12] studied the mechanical properties of PLLA materials at temperatures ranging from 70 °C to 100 °C under uniaxial deformation with nominal strain rate of 0.04 s−1 where they showed that the strain hardening occurred after a critical true strain between 125% and 280% depending on the temperature of the stretch.

The strain rate effect on the mechanical behaviour of amorphous PLLA under uniaxial testing at 75 °C with strain rates ranging from 0.01 s−1 to 0.2 s−1 showed that at low stretch ratio up to 2, there is no obvious difference on the stress-strain curves [13]. However, when the nominal strain reaches a critical value of 1.3, the influence of strain rate increase is seen through an earlier onset and more pronounced strain hardening behaviour. The same phenomenon was also found in poly (ethylene terephthalate) (PET) [14, 15].

Relatively low strain rates (< 1 s−1) was used in the previous research to highlight the temperature [9, 12] and strain rate sensitivity [13] of PLLA materials under uniaxial and biaxial conditions. However, the stretch blow moulding process typically involves biaxial deformation at high strain rates. In previous research on stretch blow moulding of PET containers at 110 °C [16] it was found that strain rates of the order of 49 s−1 and 35 s−1 were experienced in the hoop and axial directions respectively. In the blow moulding of polyamide-12 angioplasty balloons at 150 °C [17], the average strain rate in the radial direction can reach up to 133 s−1. For amorphous polymer materials at temperatures above Tg, strain rate also has a marked effect on the relaxation behaviour of the molecular chains. At low strain rates (< 1 s−1), it is reported that the strain induced crystallization of PLLA occurred during the deformation process [13, 18, 19]. However, at higher strain rates above Tg, the applied strain is faster than the rate of the chain retraction which delays the onset of crystallization. The crystallization behaviour of PLLA under biaxial stretch at a strain rate of 4 s−1 and at temperatures ranging from 80 °C to 100 °C showed that the onset of crystallization was close to the point where the deformation stopped and a final crystallinity of about 25% was measured and no clear morphology were detected within the time duration (~10 s) [20]. The phenomenon of delayed onset of crystallisation from orientation until the accomplishment of deformation was also found in the fast drawing process of PET at 15–30 °C above Tg [21].

Typically the optimum process parameters to fabricate the BVS products with better mechanical performance are found by trial and error. The aim of this work is to better understand the influence of temperature, strain rate and mode of deformation on the processing behaviour of PLLA and subsequently use this data to calibrate a mathematical model of the nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour. The material model chosen is one developed by Buckley et al. known as a ‘Glass-rubber’ (GR) model [22]. In this model, the mechanical behaviour of amorphous polymers is based on the assumed additivity of free energy of bond distortion and conformation perturbation of molecules under elongation. The model has been applied to studies on the hot-drawing of PET under biaxial stress in the temperature/strain rate regime relevant to industrial film drawing where it is able to describe the yield, flow and strain-hardening behaviour of PET [23, 24].

Furthermore, the GR model has been adopted to predict the mechanical behaviour of PET in the stretch blow moulding process for containers [25,26,27,28], which are formed in a similar manner to that of PLLA BVS. The GR model can capture the strain-hardening behaviour through the temperature range and has also been used to describe the nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour of polymers, such as polystyrene (PS), poly-methyl methacrylate (PMMA) [23, 29, 30]. The observed mechanical behaviour of PLLA [31] at temperatures above Tg under biaxial stretch shows similar features to PET [14], suggesting that this model is also a good choice to simulate the constitutive behaviour of PLLA.

In this study, the PLLA material was initially characterized by DSC and DMA to determine the available temperature window for the manufacture process whilst the mechanical behaviour was studied by biaxial stretch testing experiments at temperatures between 70 °C and 100 °C at strain rates of 1 s−1, 4 s−1 and 16 s−1 respectively i.e. at conditions mimicking the stretch blow moulding process. Finally, the GR model with the parameters calibrated from the experimental data was adopted to simulate the mechanical response of PLLA during deformation above the Tg.

Experimental characterisation of the materials

The material was supplied by Corbion with brand name PURAPOL LX175. It is a high viscosity, low flow, amorphous, transparent resin suitable for film extrusion, thermoforming or fibre spinning. It is in crystalline white pellets form with minimum 96% L-isomer of stereochemical purity, i.e. mostly PLLA and with specific gravity of 1.24 g/cm3. The average molecular weight (Mw) is 231,131 g/mol. The pre-dried PLLA pellets were processed by an extruder at melting state and quenched on a casting roll to form sheets with thickness of 0.5 mm. Thermal analysis of the extruded PLLA sheets was performed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). Using a Model DSC 6 developed by PerkinElmer, PLLA sheet samples of 6 to 10 mg were put into aluminium pans and heated at 5 °C/min, i.e. the lowest heating rate of the equipment, in the temperature range of 30 °C to 190 °C. The glass transition temperature (Tg), onset of cold thermal crystallization temperature (Tcc) and melting temperature (Tm) were obtained from the heating curves. The crystallinity of the samples (Xc) was calculated based on Eq. (1):

where, ΔHmelting is the enthalpy induced by melting, ΔHcold is the heat of fusion induced by cold thermal crystallization, ΔH0 is the enthalpy of fusion of PLLA material with 100% crystallinity, which is 93 J/g [32]. The results obtained are plotted and shown in Fig. 2. The Tg, Tcc and Tm were observed to be approximately 57 °C, 101.69 °C and 151.58 °C, close to the reported results of amorphous PLLA materials by DSC at the same heating rate [33]. By the measured results of ΔHcold = 21.24 J/g and ΔHmelting = 22.90 J/g, the initial crystallinity was found to be 1.7%, i.e. the extruded PLLA sheet can be assumed amorphous. Regarding to the double melting peak, it can be explained by the slow rate of crystallisation and recrystallization of PLLA materials observed at low heating rates [34].

A DMA TRITEC2000 instrument was used to conduct the dynamic mechanical thermal analysis (DMA). The dimension of the amorphous PLLA specimen used was 8.0 mm × 7.0 mm × 0.5 mm and the test was set to tension mode. The displacement was set to 0.05 mm (1% nominal strain) and measurements were taken at a frequency of 1 Hz. The temperature ramp rate was set to 2.0 °C/min starting at 25 °C, increasing to a final temperature of 110 °C when crystallisation happens and the molecular structure changes. The storage modulus (E’), loss modulus (E”) and the ratio between loss and storage modulus (tanδ) from the DMA test are shown in Fig. 3. The Tg obtained by the peak of the loss modulus and the half height value of the drop in storage modulus (E’) is 63 °C thus indicating a change of physical properties [35]. This is 6 °C higher than that observed by the DSC and the discrepancy between the values of the glass transition measured by the two methods can be explained by the fact the Tg is strongly influenced by the frequency of deformation [36]. As the frequency of the test increases, the molecular relaxations can only occur at higher temperatures and therefore, Tg increases with the increasing frequency. Below 50 °C, the PLLA shows mechanical properties of a glassy polymer with a relatively high storage modulus of ~1.4 GPa. Beyond the glass transition region, the storage modulus shows a rubbery plateau at 84 °C until the modulus increases at 98 °C indicating the onset of cold crystallization [33, 37].

Based on these results, the temperature window for the biaxial stretch testing was set between 70 °C and 100 °C, i.e. in the regime between Tg and Tcc.

Biaxial stretch testing

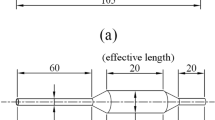

The biaxial stretching of the PLLA sheet samples was conducted using customized equipment at Queen’s University Belfast, UK [14]. As shown in Fig. 4a, a 76 mm × 76 mm square sample was fixed by four groups of grips in two directions. The sample was heated to above Tg by two hot air heaters placed directly above and below the sample resulting in convective heat transfer. Two thermocouples were placed on the top and bottom surfaces of the sheet to monitor and control the temperature. Two-directional stretch with controlled speeds in both directions was achieved by a mechanism which was actuated by two servomotors. Both equal biaxial (EB) and constant-width (CW) stretch can be achieved by controlling the movement in two in-plane directions (Fig. 4b). By using this equipment setup, thermal homogeneity of testing samples was found by a thermal imaging camera and an average temperature of 109.3 °C was measured at the temperature set of 110 °C, indicating an error of 0.64% (Fig. 4c) [38]. A testing sheet marked with crossed lines forming 10 mm × 10 mm grids before stretch (Fig. 4d) exhibited uniformly-spaced lines forming 35 mm × 35 mm grids after applying the stretch ratio of 3.5, confirming the homogeneous deformation in the process [38]. During deformation, the forces were measured by two load cells with a maximum measurement of 250 N placed on a single grip on each axis. The measured force can be transformed to the overall force on the PLLA samples [39]. The data was recorded using a LabView interface. The change in speed of the servomotor helped to achieve average nominal strain rates of 1 s−1, 4 s−1 and 16 s−1. The PLLA sheet samples were stretched until break, slip out from the grips or until they reached a maximum nominal strain level of 3.0. Three repeat tests were conducted for each test conditions and the results presented in this work are the average readings obtained from the three tests. The stress-strain curves were obtained by processing the data of force and displacement, to calculate the true stress, by assuming the material to be incompressible.

Glass-rubber model

In the modified GR model [24], viscous behaviour was incorporated in the conformational part to capture distinct strain hardening behaviour at different processing temperatures, proposing two Maxwell networks to represent the viscoelastic behaviour (Fig. 5).

The total stress σ consists of a bond-stretching stress σb and a conformational stress σc as shown in Eq. (2). More details on the splitting of bond-stretching stress and conformational stress can be found in [22]:

In the three principal directions, only normal stress exists and the total stress can be expressed by Eq. (3) assuming that the deformation starts from a stress-free state:

Where sib is the deviatoric bond-stretching stress, Kb is bulk modulus and ej is the principal natural strain.

The differential equations for bond-stretching stress and conformational stress of the two networks in three principal directions can be expressed by the Maxwell relation. In Eq. (4) for bond-stretching stress, sib is the deviatoric bond stretching stress, where Hooke elasticity is incorporated in the Maxwell network by shear modulus (Gb). Based on the assumption of incompressibility, sib is equal to the bond stretching stress σb. Non-Newtonion viscosity in Eq. (4) arises from the relaxation time τ (defined in Eq. (5)) and μ is the viscosity with dependence on process temperature, structural temperature and stress level [22]. In Eq. (6), the conformational stress incorporates hyper-elasticity through an Edwards-Vilgis strain energy function (Ac), where J is the determinant of the deformation gradient tensor. The total stretch is split into two components, the principal network stretch (λin) and the principal slippage stretch (λis) (Eq. (7)) [24]. The slippage stretch is calculated assuming a non-Newtonian relationship with a slippage viscosity (γ) and deviatoric conformational stress (sic) (Eq. (8)). Further details of the model are already detailed by Buckley et al. [22,23,24].

The stretching process is considered as homogeneous deformation with constant nominal strain rate under equal biaxial stretch (EB) or constant-width stretch (CW). An explicit integration method was used to solve Eq. (4) and obtain the evolution of stress under different strain rates [40].

Results and discussion

Mechanical behaviour

The mechanical behaviour of PLLA under biaxial stretch above Tg is investigated as a function of temperature and strain rate during two deformation modes. The data incorporates the critical conditions of the stretch blow moulding process, where the temperature range spans from just above Tg (70 °C) to near Tcc (100 °C), the strain rates range from 1 s−1 to 16 s−1 and the mode of deformation varies between equal biaxial and constant-width stretch.

Alongside other properties, the anisotropy of the PLLA sheets above Tg was also studied. For this purpose, the data along two directions, namely, the machine direction (MD) and transverse direction (TD) of the extrusion process is compared. The results at temperatures of 80 °C and 90 °C under two critical strain rates (1 s−1 and 16 s−1) under equal biaxial stretch (EB) conditions are plotted to compare the MD and TD and are shown in Fig. 6. A nearly coincident mechanical response is evident in the two directions, suggesting the effect on the morphology of molecular chains for PLLA sheets from the extrusion process under equal biaxial stretch (EB) can be neglected. For clarity of presentation, the mean stress values of three repeats in the MD direction of PLLA sheet will only be presented in the following sections.

Influence of temperature

The stress-strain data of PLLA during EB stretch at temperatures ranging from 70 °C to 100 °C in increments of 10 °C with strain rates of 1 s−1, 4 s−1 and 16 s−1 are shown in Fig. 7. It is observed that the maximum nominal strain before failure at the lower temperatures is significantly lower at 70 °C (1.5) and 80 °C (2.5) compared to tests at the higher temperatures of 90 °C and 100 °C, which don’t fail when stretched to the maximum strain of 3.0. From Fig. 7, it can be seen that the stress-strain behaviour of PLLA shows strong temperature dependence under different strain rates above Tg where it gives a stiffer response as the temperature decreases. Near Tg at 70 °C, when the strain rate reaches 16 s−1 (Fig. 7c), four distinct regions of the stress-strain curve can be identified: an initial elastic response followed by yielding, stress viscous flow and strain hardening. The amount of viscous flow increases with increasing temperature and decreases with increasing strain rate. A similar strain hardening slope at temperatures of 70 °C and 80 °C can be found at different strain rates whilst the slope decreases at temperatures between 90 °C and 100 °C, indicating the onset of entanglement slippage. The entanglement slippage arises due to the strain hardening being delayed with increasing temperature and is thought to be caused by stress relaxation as a result of axial diffusion of entire molecules at the higher temperatures [22, 24].

Influence of strain rate

Based on the data obtained under the same temperature conditions, the influence of strain rate on PLLA sheets under EB deformation is shown in Fig. 8. Due to the big difference in stress induced across the temperature range, for ease of comparison, the data for 70 °C and 80 °C is presented in Fig. 8a whilst the data for 90 °C and 100 °C is presented in Fig. 8b. The data in Fig. 8a indicates strong strain rate dependence at different stages of deformation for the two temperature conditions, 70 °C and 80 °C. A similar strain hardening slope is visible for all strain rates. At a temperature of 70 °C, strain hardening occurs at a nominal strain of approximately 0.5 at all three strain rates. At a temperature of 80 °C, the nominal strain for the onset of strain hardening is approximately 1.7, 1.5 and 1.0 for strain rates of 1 s−1, 4 s−1 and 16 s−1 respectively. At higher temperatures (Fig. 8b), the strain rate dependence still exists but to a lesser extent. Comparing the 90 °C and the 100 °C data, at the same strain rate, strain hardening at the temperature of 90 °C is more distinct with the gradient of strain hardening being significantly steeper. The strain hardening behaviour at 100 °C is limited, indicating that the material needs to be stretched beyond a nominal strain at 3.0 to induce it. It can be seen at strain rates of 16 s−1, at temperatures of 70 °C, 80 °C and 90 °C that the slope of the strain hardening curve is significantly reduced. This can be explained by the self-heating caused by viscous dissipation that has also been observed in the biaxial stretch of PET [14].

Influence of deformation mode

Equal biaxial (EB) testing provides a deformation with the same in-plane stretch ratios in each direction. However, during the stretch blow moulding process, the material experiences a range of deformation modes [41]. As highlighted in Fig. 4b, constant-width (CW) stretch testing involves stretching in one direction whilst being fixed in the transverse direction. The comparison for stress-strain data of PLLA under CW and EB at different conditions is shown in Fig. 9. Similar to an EB deformation, the deformation occurring during the CW conditions also shows strong temperature dependence and there is not a big difference on the initial stiffness for the two types of deformation modes. It can therefore be assumed that the contribution of the bond-stretching component of stress due to the intermolecular interaction is independent of the deformation mode. The extent of stress viscous flow for constant width (CW) deformation is much wider than the equal biaxial (EB) deformation at the same processing condition. For example, at strain rate of 1 s−1 and temperature of 70 °C, CW deformation covers a stress viscous flow range of 0.2 to 1.2 compared to 0.2 to 0.7 for equal biaxial (EB) deformation. The strain hardening behaviour is also obviously different for the two kinds of deformation. The strain hardening occurs at a lower strain and more rapidly under EB deformation compared to CW deformation. It can be concluded that under finite strain, the contribution of conformational interaction is significantly affected by the deformation mode. These results suggest that the effect of deformation mode, temperature and strain rate of PLLA has similar characteristics to PET, especially above Tg [14], thus providing confidence that the GR model is a good option for representing the mechanical behaviour of PLLA.

Constitutive modelling of PLLA

From the experimental data, the material parameters for PLLA in the GR model shown in equations (2) to (5) can be calibrated based on a step-by-step approach as presented by Buckley et al. for PET [23, 24]. Material parameters controlling the initial slope of stress-strain curves need to be found first to represent the elastic behaviour under small strain. In the GR model, the value of the shear modulus near Tg determines the slope for the initial stiff stress-strain response within the nominal strain ranging from 0 to 0.2. By considering incompressibility, the tensile elastic modulus under small strain is three times the shear modulus. From Fig. 3, the storage modulus corresponding to the value of Tg was found to be 112.5 MPa at 63 °C, similar to previous measurement from the literature for amorphous PLLA materials (~80 MPa) [18], thus giving an estimated shear modulus of 37.5 MPa.

Eyring plot

The Eyring process can be used to estimate the yield stress at the same temperature under different strain rates. The bond-stretching yield stress can be arranged in an explicit expression by Eq. (9) [23], where σy is the yield stress at yield stretch λy, dλ/dt is the stretch rate, ξ is the ratio of bond-stretching stress of the two in-plane directions that can be obtained by Eq. (10) [23], where θ is the ratio of in-plane natural strain-rates (θ = 1 for EB deformation and θ = 0 for CW deformation), μ0 is the viscosity at temperature T, Vp and Vs are pressure and shear activation volume respectively and R is the gas constant. The unit of temperature (T) used in all equations is in Kelvin. The relationship can also be expressed linearly between the ratio of yield stress to temperature and the ratio of extension rate to yield stretch by Eq. (11) [23]. The yielding point is more distinct for the mechanical behaviour at temperatures near the glass transition region, hence a temperature of 70 °C is chosen to determine the sensitivity of yield stress to strain rate. For EB deformation at 70 °C, the nominal stress-strain curves at strain rates from 1 s−1 to 16 s−1 are shown in Fig. 10a. The yield point is considered as the peak of the nominal stress. The peak is clearly identifiable at strain rates of 16 s−1 and 8 s−1 at a nominal strain of 0.2 and this same value of strain is used for defining the value of yield stress at the lower strain rates where there is no obvious peak. The resulting data points with a fitted linear regression are shown in Fig. 10b with R2 = 0.96556, where R2 is the coefficient of determination. The slope of the line (m = 0.0116) in Eq. (11) is used to determine Vp and Vs in Eq. (9). An equation giving the relationship between Vp and Vs needs to be also determined. In the GR model, the ratio between Vp and Vs determines the value of viscosity for the bond-stretching component at small strains. From the DMA test, at a frequency of 1 s−1 (ω') the tensile loss modulus (E”) at temperature of 70 °C is found to be 2.75 MPa and using Eq. (12) [42], a shear viscosity (μ0) of 0.9167 MPa·s can be calculated. By combining Eq. (9) and the calculated bond-stretching stress of 1.865 MPa at 70 °C in Eq. (13) (see section 5.2.2), a viscosity of 0.9167 MPa·s can be used to obtain Vp and Vs.

Bond-stretching stress

To allow the bond stretching stress to fully relax over the timescale of the biaxial experiment, the yield stress at the lowest strain rate (1 s−1) over the temperature range 70 °C to 100 °C is chosen to obtain the bond stretching stress parameters. By assuming that the bond stretching stress has fully relaxed at the highest temperature (100 °C), from Eq. (2) it can therefore be assumed that the total stress is equivalent to the conformational stress. At this temperature at a strain of 0.2, the total stress was found to be 0.698 MPa. This value is therefore subtracted from the total stress for temperatures less than 100 °C to obtain the bond-stretching stress ranging from 70 °C to 90 °C (Table 1).

By applying Eq. (13) [23], the viscosity at these temperatures can also be deduced. The relationship between viscosity and temperature in Eq. (14) [22, 43] can be used to obtain the Cohen-Turnbull constant Cv, Vogel temperature Tvogel and Activation Enthalpy H0, reference temperature T*, the viscosity μ0* at reference temperature and fictive temperature Tf through a least-squares curve fitting method. The data and corresponding fitted curve are shown in Fig. 11 with R2 = 0.99823. From the figure, it can be seen that the viscosity of PLLA at 70 °C is about 0.9196 MPa·s, which is in accordance with the DMA test (0.9167 MPa·s). For temperatures higher than 90 °C, the bond-stretching viscosity is extrapolated based on Eq. (14).

By an explicit numerical solution of Eq. (4) [29], the bond-stretching stress with respect to temperature and strain rate can be obtained, which is plotted in Fig. 12. It can be seen that this model is able to describe the temperature dependence as well as the strain rate dependence for bond-stretching viscoelasticity. In Fig. 12a, the bond-stretching stress at different temperatures with a strain rate of 1 s−1 shows that at the same strain rate, there is big difference in the mechanical response between 70 °C and 80 °C due to the change of viscosity near the glass transition. It can be also seen that at a strain rate of 1 s−1 the contribution of the bond-stretching stress temperatures at 90 °C and above is negligible. In Fig. 12b, it can be seen that at 70 °C, the bond-stretching yield stress increases with the strain rate and induces steeper relaxation behaviour.

Conformational stress

With the bond stretching stress now calculated, the conformational stress can be found by subtracting it from the total stress available from the experiment, in accordance with Eq. (2). The conformational stress during equal biaxial (EB) deformation at temperatures between 70 °C and 100 °C is shown in Fig. 13a. The free energy function of the conformational stretch is based on the Edwards-Vilgis (EV) model expressed by Eq. (15), where Ac is the energy function, Ne is material density of slip-links for entanglement, kb is Boltzmann constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, η is slip-link looseness factor, λi is the principal stretch. It can be seen that the EV model is primarily dependent on the stretch in the principal direction and since T is the temperature in Kelvin, the influence of temperature is minimum. However, the conformational stress-strain curves in Fig. 13a show a strong dependence on temperature, indicating that a viscous effect also exists [24]. The conformational data at the lowest processing temperature (70 °C) where the slippage can be assumed to be negligible [23, 24] is therefore used to fit the EV model at different strain rates for both EB and CW deformation. The constants Ns, α and η in the EV model are calibrated through a least-squares curve fitting method to obtain the deviatoric conformational stress (sic) based on Eq. (16), where hydrostatic stress (p) is assumed to be zero due to the incompressibility, i.e. sic = σic. The comparison between data and model for the two deformation modes is shown in Fig. 13b. It can be seen that a good prediction for conformational stress for both EB and CW deformation at the temperature of 70 °C is achieved.

As it is assumed that there is no conformational slippage at 70 °C, the traditional GR model [22] without the viscous effect in the conformational part can be used to predict the stress-strain relations at this temperature. By using the material parameters obtained from the previous procedure, the modelling results are plotted in Fig. 14. The prediction of the model shows good results for both EB and CW deformation at all strain rates. The strain rate dependence of the initial stiff response, the stress flow and strain hardening regions can all be captured.

Conformational slippage

As expressed in Eq. (7), the total stretch is split into two components of network stretch (λn) and slippage stretch (λs), where λ = λn λs. At higher temperatures and at the same stretch as that of 70 °C, the decrease in conformational stress is assumed to be as a result of the slippage stretch, which has no contribution on stress. The network stretch can be obtained by taking 70 °C as a reference temperature where no slippage occurs. The slippage stretch can be deduced for higher temperatures by calculating the difference in stretch for corresponding stresses between 70 °C and the stress at the temperature of interest. This is highlighted in Fig. 15a, where a calculation is shown for a single stress point at 80 °C. By using this method, the slippage stretch at temperatures of 80 °C, 90 °C and 100 °C at EB deformation modes is obtained and is shown in Fig. 15b. It shows that there are different evolutions of slippage stretch at each temperature. At temperatures of 80 °C and 90 °C, after a certain stress, the slippage stretch becomes stable, indicating the arrest of the viscous effect, corresponding to the strain hardening stage, this is known as the critical slippage stretch (λscrit). At a temperature of 100 °C, no obvious arrest of slippage stretch is found and the peak slippage stretch value is used to identify the critical stretch. In Fig. 15b, the adopted critical slippage stretch λscrit for 80 °C, 90 °C and 100 °C was 1.29, 1.75 and 2.68 respectively indicated by the dashed line.

During the deformation, as the maximum principal slippage stretch λsmax at any time t increases to the critical value λscrit, the slippage viscosity (γ) will increase to infinity. This is shown in Eq. (17), where γ0 is the initial slippage viscosity at different temperatures without deformation and γ is the slippage viscosity during deformation. The evolution of the ratio between the real-time slippage viscosity and the original slippage viscosity at different temperatures is shown in Fig. 16a. To minimise the effect of self-heating, a strain rate of 1 s−1 is chosen to characterise the slippage viscosity at temperatures from 75 °C to 100 °C by determining the parameters that gave the best fit between the experimental stress-strain data and the prediction from the full constitutive model. The dependence of slippage viscosity on temperature is expressed by the Fulcher Equation (18) [42], where γ0* is slippage viscosity at the reference temperature, Cs is slippage Cohen-Turnbull constant, Ts* is slippage reference temperature and Tvogels is the slippage Vogel temperature. The data for slippage viscosity and the corresponding fit with Eq. (18) are shown in Fig. 16b with R2 = 0.99469.

Model predictions and comparisons with experiments

From the calibration process, all the constitutive parameters of the PLLA material are deduced and shown in Table 2.

With the parameters provided in Table 2, the GR model can be used to predict the constitutive behaviour of PLLA under the same experimental conditions as that of the biaxial stretch testing, the results of which are shown in Fig. 17. It can be seen the simulation results are found to corroborate with the experiments and the dependence of mechanical behaviour of PLLA on temperature, strain rate and deformation mode at temperatures above Tg is replicated. The ability of the GR model in capturing the elasticity, stress flow and strain hardening characteristics of PLLA is demonstrated as well.

In order to evaluate the accuracy between the results from simulation (\( {\widehat{y}}_i \)) and experiment (yi) over the whole data points (n) quantitatively, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) can be calculated based on Eq. (19). By introducing the maximum value (ymax) and minimum value (ymin) from experiment, the normalized root mean square deviation (NRMSD) is used to compare the accuracy at different processing conditions based on Eq. (20).

The results of NRMSD at each processing condition are shown in Fig. 18. The calculated overall average NRMSD is approximately 7.2% (EB deformation) and 15.5% (CW deformation) respectively, which clearly indicates the high accuracy of modelling results and excellent performance of the constitutive model. Under EB deformation, most cases have a NRMSD lower than 10% except for the case of strain rate equal to 16 s−1 at a temperature of 100 °C. At this condition, the simulation from the GR model shows a bigger viscous flow region compared with experiment and a late onset of strain hardening. This is probably due to the slippage viscosity only being temperature dependent and not strain rate dependent. Since the slippage parameters including viscosity and critical slippage stretch are fitted at a strain rate of 1 s−1 it is unable to accurately capture the high strain rate data.

Discussion

In contrast to the mechanical tests of PLLA above Tg at low strain rate conditions (<1 s−1) already in the literature [13] which concluded limited influence of strain rate, we have demonstrated that biaxial stretching at high strains (1 s−1 to 16 s−1) shows strong strain rate dependence especially on the yield stress. This is therefore an important feature that needs to be captured in simulating PLLA behaviour in stretch blow moulding where preliminary studies in our lab have demonstrated that the strain rate reaches an average value of 15 s−1. The results of these stretch blow moulding experiments and the use of the model developed here to predict the behaviour will be presented in a future publication. One of the issues we have not addressed in this paper is the sequential deformation behaviour whereby the polymer is stretched initially in one direction and subsequently in a second direction. The literature shows that this has a significant effect on the microstructure evolution [31, 44] and hence on the constitutive behaviour of the materials after stretch [11]. We have generated the relevant data and explored the ability of the model to fit it in a previous study [45] and have demonstrated its capability of capturing this behaviour.

The biggest discrepancy of the model occurs at conditions of high temperature and a constant width (CW) mode of deformation. We believe the main cause of this is primarily due the viscosity in the bond stretching component (which primarily determines the yield behaviour and its dependence on strain rate) and the slippage viscosity (which primarily determines the strain hardening behaviour) are both found though equal biaxial (EB) data alone. At high temperatures of CW deformation with the stress levels being low, the sensitivity of these viscosities on the model behaviour is high. An alternative approach of fitting the viscosity parameters using data from both modes of deformation and having a strain history dependent viscosity will be required to resolve this [38].

Conclusions

PLLA has been biaxially stretched at conditions relevant for stretch blow moulding above Tg (~60 °C) and below Tcc (~100 °C) in the strain rate range of 1 s−1 to 16 s−1. The results have demonstrated nonlinear viscoelastic behaviour with strong dependence on temperature, strain rate and mode of deformation. We have also demonstrated the capability of the glass-rubber (GR) model to capture this complex biaxial stress-strain behaviour over a wide range of process conditions with an average deviation of 7.2% and 15.5% in EB and CW deformation respectively. Some limitations have been observed in the modelling at higher temperatures thought to be caused by the strain history dependence of the slippage and bond stretching viscosity not currently captured in the model. The model has the potential to be implemented in forming simulations of PLLA BVS and thus optimise their design and manufacture.

References

Garg S, Serruys P (2009) Biodegradable and non-biodegradable stents. Minerva Cardioangiol 57:537–565

Onuma Y, Serruys PW (2011) Bioresorbable scaffold: The advent of a new era in percutaneous coronary and peripheral revascularization? Circulation 123:779–797. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.971606

Ailianou A, Ramachandran K, Kossuth MB et al (2016) Multiplicity of morphologies in poly (l-lactide) bioresorbable vascular scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113(42):11670–11675. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1602311113

Naseem R, Zhao L, Liu Y, Silberschmidt VV (2017) Experimental and computational studies of poly-L-lactic acid for cardiovascular applications: recent progress. Mech Adv Mater Mod Process 3(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40759-017-0028-y

Schiavone A, Qiu T-Y, Zhao L-G (2017) Crimping and deployment of metallic and polymeric stents -- finite element modelling. Vessel Plus 1(1). https://doi.org/10.20517/2574-1209.2016.03

Glauser T, Gueriguian V, Steichen B, et al (2013) Controlling Crystalline Morphology of a Bioabsorbable Stent

Huang B, Gale DC, Gueriguian V (2012) Method of Fabricating Stents from Blow Molded Tubing

Wang P-J, Ferralis N, Conway C et al (2018) Strain-induced accelerated asymmetric spatial degradation of polymeric vascular scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci:201716420. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1716420115

Chapleau N, Huneault MA, Li H (2007) Biaxial orientation of polylactide/thermoplastic starch blends. Int Polym Process 22:402–409. https://doi.org/10.3139/217.2070

Zenkiewicz M, Richert J, Rózański A (2010) Effects of blow molding ratio on mechanical properties of polylactide nanocomposite films. Polimery/Polymers 55:869–876

Løvdal A, Andreasen JW, Mikkelsen LP et al (2016) Characterization of biaxial strain of poly(l-lactide) tubes. Polym Int 65:133–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/pi.5040

Stoclet G, Seguela R, Lefebvre JM et al (2010) Strain-induced molecular ordering in polylactide upon uniaxial stretching. Macromolecules 43:1488–1498. https://doi.org/10.1021/ma9024366

Zhang X, Schneider K, Liu G et al (2011) Structure variation of tensile-deformed amorphous poly(l-lactic acid): effects of deformation rate and strain. Polymer (Guildf) 52:4141–4149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2011.07.003

Menary GH, Tan CW, Harkin-Jones EMA et al (2012) Biaxial deformation and experimental study of PET at conditions applicable to stretch blow molding. Polym Eng Sci 52:671–688. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.22134

Salem DR (1992) Development of crystalline order during hot-drawing of poly(ethylene terephthalate) film: influence of strain rate. Polymer (Guildf) 33:3182–3188. https://doi.org/10.1016/0032-3861(92)90232-L

Yan S, Menary G, Nixon J (2017) A novel methodology to characterize the constitutive behaviour of polyethylene terephthalate for the stretch blow moulding process. Mech Mater 104:93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2016.10.006

Menary GH, Armstrong CG (2006) Experimental study and numerical modelling of injection stretch blow moulding of angioplasty balloons. Plast Rubber Compos 35:348–354. https://doi.org/10.1179/174328906X143877

Stoclet G, Seguela R, Vanmansart C et al (2012) WAXS study of the structural reorganization of semi-crystalline polylactide under tensile drawing. Polymer (Guildf) 53:519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2011.11.063

Zhou C, Li H, Zhang W et al (2016) Direct investigations on strain-induced cold crystallization behavior and structure evolutions in amorphous poly(lactic acid) with SAXS and WAXS measurements. Polym (United Kingdom) 90:111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2016.03.014

Mahendrasingam A, Blundell DJ, Parton M et al (2005) Time resolved study of oriented crystallisation of poly(lactic acid) during rapid tensile deformation. Polymer (Guildf) 46:6009–6015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2005.05.081

Mahendrasingam A, Blundell DJ, Martin C et al (2000) Influence of temperature and chain orientation on the crystallization of poly(ethylene terephthalate) during fast drawing. Polymer (Guildf) 41(21):7803–7814. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00129-4

Buckley CP (1995) Glass-rubber constitutive model for amorphous polymers near the glass transition. Polymer (Guildf) 36:3301–3312. https://doi.org/10.1016/0032-3861(95)99429-X

Buckley CP, Jones DC, Jones DP (1996) Hot-drawing of poly(ethylene terephthalate) under biaxial stress: application of a three-dimensional glass-rubber constitutive model. Polymer (Guildf) 37:2403–2414. https://doi.org/10.1016/0032-3861(96)85352-3

Adams AM, Buckley CP, Jones DP (2000) Biaxial hot drawing of poly(ethylene terephthalate): measurements and modelling of strain-stiffening. Polymer (Guildf) 41(2):771–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(98)00834-9

Yang ZJ, Harkin-Jones EMA, Armstrong CG, Menary GH (2004) Finite element modelling of stretch–blow moulding of PET bottles using Buckley model: plant tests and effects of process conditions and material parameters. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part E J Process Mech Eng 218:237–250. https://doi.org/10.1243/0954408042466990

Menary GH, Tan CW, Armstrong CG et al (2010) Validating injection stretch-blow molding simulation through free blow trials. Polym Eng Sci 50:1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/pen.21555

Nixon J, Menary GH, Yan S (2017) Finite element simulations of stretch-blow moulding with experimental validation over a broad process window. Int J Mater Form 10:793–809. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-016-1320-9

Zimmer J, Stommel M (2013) Method for the evaluation of stretch blow molding simulations with free blow trials. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 48. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/48/1/012004

Li HX, Buckley CP (2009) Evolution of strain localization in glassy polymers: a numerical study. Int J Solids Struct 46:1607–1623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2008.12.002

Dooling PJ, Buckley CP, Rostami S, Zahlan N (2002) Hot-drawing of poly(methyl methacrylate) and simulation using a glass - rubber constitutive model. Polymer (Guildf) 43:2451–2465

Ou X, Cakmak M (2008) Influence of biaxial stretching mode on the crystalline texture in polylactic acid films. Polymer (Guildf) 49:5344–5352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2008.09.053

Fischer EW, Sterzel HJ, Wegner G (1973) Investigation of the structure of solution grown crystals of lactide copolymers by means of chemical reactions. Kolloid-Zeitschrift Zeitschrift für Polym 251:980–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01498927

Tábi T, Sajó IE, Szabó F et al (2010) Crystalline structure of annealed polylactic acid and its relation to processing. Express Polym Lett. https://doi.org/10.3144/expresspolymlett.2010.80

Yasuniwa M, Tsubakihara S, Sugimoto Y, Nakafuku C (2004) Thermal analysis of the double-melting behavior of poly(L-lactic acid). J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys 42(1):25–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/polb.10674

Shalaby SW (1981) {CHAPTER} 3 - thermoplastic polymers. In: TURI EA (ed) Thermal Characterization of Polymeric Materials. Academic Press, pp 235–364

Bai Y, Jin L (2008) Characterization of frequency-dependent glass transition temperature by Vogel–Fulcher relationship. J Phys D Appl Phys 41(15):152008. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/41/15/152008

Martin O, Averous L (2001) Poly(lactic acid): plasticization and properties of biodegradable multiphases systems. Poly(lactic acid) 42:6209–6219

Yan S (2014) Modelling the constitutive behaviour of poly ( ethylene terephthalate ) for the stretch blow Moulding process. Queen’s University Belfast

O’Connor C (2010) Development of thermoforming process simulations and constitutive models of polypropylenes. Queen’s University Belfast

Li H, Nie W, Deng C et al (2009) Crystalline morphology of poly(l-lactic acid) thin films. Eur Polym J 45(1):123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.10.008

Nixon J, Menary GH, Yan S (2016) Free-stretch-blow investigation of poly(ethylene terephthalate) over a large process window. Int J Mater Form:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-016-1318-3

Ferry JD (1980) Viscoelastic properties of polymers, 3rd edn. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Macedo PB, Litovitz TA (1965) On the relative roles of free volume and activation energy in the viscosity of liquids. J Chem Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1695683

Ramachandran K, Miscioscia R, De Filippo G et al (2018) Tube expansion deformation enables in situ synchrotron X-ray scattering measurements during extensional flow-induced crystallization of poly L-lactide near the glass transition. Polymers (Basel) 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym10030288

Wei H, Menary G, Yan S, Buchanan F (2018) Experiment and modelling on biaxial deformation of PLLA materials under designed strain history for stretch blow Moulding. In: Recent Advances in Intelligent Manufacturing. Springer Singapore, pp 228–238

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Dr. Lukasz Figiel for extruding the PLLA sheets. The PhD scholarship was funded by Queen’s University Belfast and China Scholarship Council. Saurav Goel acknowledges partial support of the European COST Action CA15102 of the Horizon 2020.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 691238 involving Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development (Italy), University of Warwick (UK), Queen’s University Belfast (UK) and California Institute of Technology (US).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, H., Yan, S., Goel, S. et al. Characterization and modelling the mechanical behaviour of poly(l-lactic acid) for the manufacture of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds by stretch blow moulding. Int J Mater Form 13, 43–57 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-018-01463-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12289-018-01463-2