Abstract

Past research pointed to the idea that right-wing ideology and climate-change skepticism are inherently linked. Empirical reality proves differently however, since right-wing populist parties are starting to adapt pro environmentalist stances. In this paper, we look into two prominent cases of diametrical diverging environmental strategies by right-wing-populist-parties: France’s Rassemblement National and Germany’s Alternative für Deutschland. In order convey this point, we use comparative qualitative content analysis and examine several decisive determinants regarding environmental strategies of right-wing populist parties. We argue that right-wing-populism is remarkably adaptable considering political opportunity structures, even clustering in ideologically diametrical versions of the same issue while each party coherently extends its policy-orientation to its respective alignment of the issue. That means, populism might be far less ideological than assumed in the past.

Zusammenfassung

In der Vergangenheit wurde spekuliert, dass rechter Populismus und die Ablehnung gegenüber „Grüner Politik“ zunehmend konvergieren. In den letzten Jahren zeigte sich jedoch, dass dies keine allgemeingültige These ist, da rechtspopulistische Parteien vermehrt pro-ökologische Positionen vertreten. In dem vorliegenden Beitrag untersuchen wir zwei prominente Fälle divergierender Umweltstrategien rechtspopulistischer Parteien: Frankreichs Rassemblement National und Deutschlands Alternative für Deutschland. Wir untersuchen dabei die Policy-Ausrichtungen der jeweiligen Parteien in Bezug auf politische Gelegenheitsstrukturen und zeigen, dass Rechtspopulismus in diesem Gesichtspunkt weitaus anpassungsfähiger und unideologischer ist als dies in der Vergangenheit vermutet wurde. Die Erkenntnisse der vorliegenden Untersuchung deuten schließlich darauf hin, dass im rechten Populismus sogar ideologisch diametrale Versionen desselben Themas geclustert werden können. Die politische Ausrichtung beider Parteien verbleibt kohärent, während die Orientierung in puncto „Grüner Politik“ zunehmend divergiert. Um dies zu zeigen, nutzen wir eine vergleichende qualitative Inhaltsanalyse und untersuchen einige entscheidende Determinanten von Umweltstrategien rechtspopulistischer Parteien.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 To protect or not to protect? Populism and diverging perspectives on climate policy

Climate-change-policy issues in Europe have often been expressed in terms of a fight between two opposite camps: ‘the green wave’ and right-wing populism. Indeed, since Fridays for Future (FFF) has moved the danger of climate change up the agenda, right-wing populist parties (RWPs) in Europe, such as the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), have positioned themselves more prominently against pro-climate action—or rather against environmentalism more broadly. This is a seemingly obvious choice as movements like FFF and parties that promote policies like the Green Deal are typically located on the political left. RWPs have also often held congruous tendencies in the past, either denying climate change in its entirety or at least its ties to CO2 emissions and ‘manmade’ climate change (Schaller and Carius 2019). Consequently, their leaders and supporters are “often hostile to policy designed to address climate change, and […] express forms of climate skepticism that place them outside the political mainstream” (Lockwood 2018, p. 27). Forchtner et al. (2018, p. 600) even argue that there is an inherent link between right-wing ideology and climate-change skepticism.

There is a growing consensus among scientists as well as the general public that climate change poses one of the biggest challenges of our time but climate change skepticism is also on the rise. Lockwood (2018) argues that climate change skepticism can be explained from two perspectives: First, it can be rooted in the economic and political marginalization of specific groups in post-industrial societies, leaving large numbers of people feeling like they are ‘left behind’ by the effects of globalization and technical change and that policy agendas of mainstream political parties are not representing them. Second, it may be tied to their ideology: they see climate change action as an expression of hostility to liberal cosmopolitan elites, rather than an engagement with the issue of climate change itself. While not disputing these claims, we try to offer a more nuanced picture, especially since the assumption that there is an inherent link between right-wing ideology and climate-change skepticism by Forchtner et al. (2018) is quite compelling—but it clashes with empirical reality.

There are some outliers among RWPs which currently attempt to capture ‘green issues’, making it a priority on their political agenda. Austria’s Freedom Party (FPÖ) or France’s Rassemblement National (RN), for instance, are parties that convey climate-protection policy positions. Other than the inherent-link-thesis might suggest such a standpoint is compatible with right-wing populist ideology as the conservation of regional habitats aligns with their conviction to protect the homeland, for instance (Olwig 2003; Forchtner and Kølvraa 2015). This does not necessarily have to relate to a notion of ‘Heimatschutz’, implying a far-right ideational basis. Though, of course they can be, as we will convey using the AfD as an example. The rationale underlying pro-environment stances by RWP’s may, however, also be grounded in the respective political culture at large, building on a notion of protection of national culture that is not necessarily exclusionary and inherent not just to RWPs but to a broad range of political parties, as is the case with the RN. As a result, environmental issues may well be communicated in positive terms conducive to the right-wing agenda and are not necessarily rejected, though the reasons for doing so may be rather nuanced.

According to Lockwood (2018), the traditionally alleged hostility of RWPs toward climate-change-action can either be traced back to structural determinants or ideology. In this paper, we especially look into structural determinants as the decisive factor regarding environmental strategies of RWPs, rejecting the proposition that these strategies are primarily reliant on ideology. We argue that right-wing-populism is much more flexible regarding climate policies than previously anticipated and convey that RWPs can adapt to contrary standpoints which do not fit the denial-pattern. However, it is essential to employ a nuanced analysis of such apparent differences. Therefore, we make a conceptual differentiation between anti-climate action and anti-environmentalism more broadly. In this way, we can account for positive stances towards environmental policy and rejection of environmental measures related to climate change at the same time. For the analysis, we rely on a political opportunity structure (POS) approach. POS provide a powerful analytical tool, especially with regard to comparative analysis. In this case, we scrutinize structural and institutional conditions in two countries with diverging strategies: Germany and France. Correspondingly, we ask the following research questions:

RQ1

To what extent do the AfD and the RN as ideologically similar and cohesive RWPs convey diverging strategies concerning environmental and climate policy? If so, how can these differences be explained?

RQ2

How do RWPs integrate opposing positions in their overall similar political orientation?

By conceptualizing populism as a strategy, we argue that the endorsement of climate protection or the denial of climate change might be a result of strategic alignments promoted by a window of political opportunity. We furthermore analyze the strategy of right-wing parties in terms of their attitude toward climate-protective policies. We show that it is more likely that systemic variables and POS are playing a leading role considering the respective tendencies than ideology. In particular, we argue that specificities of the party systems in terms of presence and strength of green parties as well as the overall salience of environmental concerns are key factors. Domestic politics, institutional settings and short-term contextual events also seem to play a role.

The AfD and the RN are two of the most prominent cases in Europe and we examine both via a qualitative content analysis (QCA) of mission statements, party manifestos, statements by party leaders as well as Tweets. The QCA is geared towards revealing populist rhetoric as is standard in populism studies (e.g. Rooduijn and Akkerman 2017). Structural determinants are assessed separately. There are no comparable analyses on this topic, therefore we consider this a first exploratory study.

2 Populism and political opportunity

There is a plurality of definitions of populism leading to varying conceptualizations. Populism can be understood as an ideology (e.g. Mudde 2004; Stanley 2008), a discourse (Aslanidis 2016; Laclau 2005), a political logic (Judis 2016; da Silva and Vieira 2019), a political style (Jagers and Walgrave 2007; Moffitt and Tormey 2014), or as a mobilization-strategy (Barr 2019; Taggart 2017; Weyland 2001). Although there are overlaps between the approaches, the interpretation as a mobilization-strategy holds promising explanatory potential for the kind of policy-positioning assessed in this paper. Taggart, for instance, compares RWPs to chameleons: a populist strategy is adapted to its environment in order fit into different constellations and situations (Taggart 2000; Mény and Surel 2002). An ideological characteristic would most likely be more predetermined. Populist mobilization thus describes any sustained political project combining popular mobilization with populist rhetoric (original emphasis, Jansen 2011, p. 82). Following Raschke and Tils, political strategies are usually not unilateral top-down processes. Mostly, they are reactive and thus coordinated with society’s sensitivities (Raschke and Tils 2007, p. 337 f.). Usually, political activities include mobilizational as well as discursive practices. From this perspective, it is not the ideas or promoted policies that count—it is their strategic use that matters. Furthermore, comparing varying national, economic, political and social differences, the concept of populism as a strategy is well suited for comparative analysis (Barr 2017).

Analyzing populist strategies, a political opportunity approach may reveal the conditions under which a party chooses one strategy over another. Political opportunity theory largely originated with social movement scholars aiming to explain the dynamics of emergence and mobilization (Giugni 2011; Meyer and Minkoff 2004). The concept has since been used in different contexts, among them the analysis of party politics (e.g. Koopmans and Muis 2009; Rydgren 2004) and comparative politics (Kriesi et al. 1992, 1995; Kitschelt 1986; Rucht 1996). McAdam et al. see the potential for mobilization determined by three broad sets of factors (McAdam et al. 2011, p. 2):

-

1.

Political opportunities: The structure of political opportunities and the political constraints a movement faces. A change in the problematic situation or in the informal power relations can be identified as a collective goal.

-

2.

Mobilization structures: An informal or formal organizational form can be developed in parallel with the protest potential.

-

3.

Framing processes: “the collective processes of interpretation, attribution, and social construction that mediate between opportunity and action” (McAdam et al. 2011, p. 2).

Studies of RWP mobilization further suggest factors that are of particular importance for right-wing parties (see for instance Kestilä and Söderlund 2007; Koopmans and Muis 2009; Rydgren 2010). The majority of research in this area thus are designed with a two-fold approach to explaining RWP success: more or less fixed institutional settings such as electoral or party system, and short-term contextual events that trigger situational political opportunities.

Spies and Franzman (2011) convey that the structure of the political system is relevant, e.g. mainstream party convergence, the position of the established right, and party system polarization are decisive concerning RWP electoral success. Similarly, Arzheimer and Carter (2006) view long-term institutional and party system variables as well as more short-term volatile variables as crucial.

We suggest that these approaches do not just explain RWP success, however. They are also useful tools to assess why and how RWPs create successful strategies in the first place. In line with prior research, we thus focus on the largely stable party system variable as well as the salience of ‘green issues’. In addition to fitting well into established POS studies of RWP success, these variables have also been proven to be strong determinants of climate policy positions (Marks and McAdam 1996). In this case, policy positions are understood as an openly expressed point of view towards a particular topic. Specifically, we assess RWP environmental policy positions in relation to the recent surge in popularity of green issues and the emergence of green social movements (for instance FFF) as short-term variables, and the position of green parties in the respective countries as institutional variables.

The framing of the issues is another important part of the potential for mobilization (McAdam et al. 2011, p. 2). Frame extensions in particular may show how the respective parties integrate their position with their overall political orientation. This refers to a technique with which an existing frame can strategically be expanded to reach a larger target group (Scheufele and Scheufele 2012, p. 9; Oswald 2020). It extends the constituency thereby making the frame more attractive to an audience whose ideology or interests were not, or not sufficiently, touched upon previously. This may refer to a realignment of specific interests or an expansion to content or values that can appeal to a larger number of people. The strategists are addressing concerns that are in close proximity to the interests of the target-group, but which have not yet appeared relevant to them (Conley and Heery 2007, p. 7; Snow et al. 1986, p. 472; Snow and Benford 1988, p. 478).

We argue, extending a nativist programmatical core to environmental issues is feasible because RWP’s political orientation is compatible with a pro-climate action because of “indissoluble links between the nation and the biological and physical environment” (McCarthy 2019, p. 301). This idea has roots in the ideology of the 19th century political right. But the question of how the extension is rendered compatible—especially considering both pro- and con-positions—has yet to be answered.

3 Method

Bornschier (2012) showed in a compelling argument, that France and Germany show a strong similarity of the structure of political space, which caused the question why until 2015, there was no strong RWP in Germany but in France. The varying success of the right parties might lie in a diverging behavior of the established parties Bornschier concluded—a feature that is not in place anymore in 2020. Accordingly, we decided to conduct this study on the basis of a most-similar systems approach.

To answer RQ1 we conducted a cross-regional comparative qualitative content analysis (QCA) of France’s RN and Germany’s AfD. Both parties are from the right-wing-populist spectrum and belong to the same EU parliamentary group ‘Identity and Democracy’. Even though both parties are ideologically aligned, there are also dissimilarities which limit the study: They are in very different stages of maturity, since the AfD is a very young party and still in a search-strategy-phase. The original context and development of both parties is also quite different given that the AfD used to be a fiscal-conservative party which are usually ideologically oriented towards anti-regulation and pro-business. Also, the FFF movement has had quite a different impact in each country, gaining more influence in Germany than in France. Still, we expect to see at least a similar policy orientation, since for both parties, environmentalism developed into a very prominent issue. Because party manifestos are not regularly updated, we did not only rely on such data to assess strategies and POS behind this environmental turn. We also included speeches and official party Twitter-communication between 01.01.2019 and 31.03.2020Footnote 1; for comparative purposes, we reach back into party programs of 2017 and 2018. Within this time frame, a full sample including all available material was gathered and analyzed. The sample size of all documents included amounts to n = 229. Thus, the unit of analysis is defined as the individual documents analyzed. Accordingly, one program per party was analyzed in 2017 and 2018. In 2019, a total of 74 documents for the AfD and 101 documents for the RN were coded, consisting of tweets and speeches. This was also done for 2020 with 22 documents from the AfD and 28 from the RN.Footnote 2

In order to substantiate research findings as well as increase validity, data triangulation was employed by analyzing material from several different sources. Triangulation refers to the use of different approaches to analyze and describe the same phenomenon (Benoit and Holbert 2008; Flick 2008). To develop inductive categories, the material was firstly examined to review the different positions. The QCA aims towards structuring content (Kuckartz 2018; Schreier 2012) and the coding scheme was built inductively using subsumption (see for instance Schreier 2012). After the first screening of the material, initial codes were developed based on the most common party positions found throughout the material. Because of the different nature of the material, we coded units of meaning (Kuckartz 2018) as opposed to restricting the coding units to a specific number of sentences, in order to be able to fully extract relevant content across different data sources. Coding units could thus span anything from a sentence to an entire paragraph within the respective unit of analysis, the focus being the position conveyed. Units could be coded multiple times and overlappingly. We coded the party’s positioning on the respective topic which in this context refers not to mere references of environmentalism or climate change in the material but rather had to include some evaluation and/or recommended actions. Subsequently, the codes were adapted in an iterative process to create a valid category system. This flexible approach allowed the construction of dominant and coherent patterns within the material (Löblich 2014, p. 67).

We inductively built main categories in accordance with identified environment-related issues discussed in the material: climate change, progressive energy policy, transportation and mobility, development of rural areas, environmental protection, political institutions and international agreements. We then elaborated the coding scheme using inductively derived sub-categories which correspond to a Pro and Contra stance regarding the main categories.Footnote 3 The four main lines of argumentation identified were based on anti-establishment, culture, environmentalist, or economic reasoning. These were further analyzed within the sub-categories. The provisional category system was then applied and adapted with constant addition or adaptation of categories.

Two trained coders fully coded all texts with detailed coding rules. In order to guarantee intra-coder reliability, a pilot study was carried out and the coding scheme revised once more. As each coder was responsible for one empirical example (corresponding to AfD and RN), the quality of the codes was continuously compared between coded sections during the pilot and main coding phase. During the pilot study, both coders were given samples from both parties to ensure that the same texts were coded in the same manner.Footnote 4 Table 1 illustrates how positions were coded based on our category development.

Taking into account the results of the QCA, we turn to the second part of RQ1 Here, the results are examined further in a theoretical analysis of political opportunity structures. In particular, we analyze the outcomes in the context of salience of environmental issues among the population and green party presence. Finally, we interpret the positions of the respective parties in order to answer RQ2. Again, this is largely a theory-guided analysis of the results thus far.

4 Results

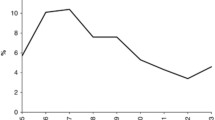

(Fig. 1)

As is evident, AfD and RN convey diverging as well as similar positions. This particularly shows when taking into account the differentiation between positions towards climate action and environmentalism more broadly. The AfD denies man-made climate change, and while the RN very explicitly does not, the pro-environmental measures they promote typically do not relate to climate change specifically, as will become clear in the following. Neither party directly references their stance often. The AfD’s denial of climate change was coded eight times as opposed to the RN’s affirmation of it (four codes). Yet, it is evident in their positions towards specific policy proposals that this appears to be assumed in the respective party output. Overall, the AfD ties its negative stance mostly to economic arguments and the attack on climate change related policies—measures are unnecessary and potentially economically harmful. Contrary to this, the RN advocates for environmental measures especially through alluding to notions of ‘souveraineté’, strengthening and protecting the local (political) culture of France (Lüsebrink 2018, p. 131 f.; Craiutu 1999, p. 481 f.).

Due to these diverging strategies, different foci are set by the parties as is evident considering Table 1. Analyzing specific policies, we found that the AfD strongly emphasizes the topics of energy and transport. Firstly, the AfD is extremely hostile toward progressive energy policies. This is one of their most referenced topics overall as well as part of their current discourse on climate change. Economic reasons are by far the most frequently cited for this position, accounting for 54 out of the 76 codes in the contra-progressive energy policy category. In terms of content, the AfD highlights increasing costs regarding the infrastructural changes necessary for switching from primarily coal and nuclear energy to renewables as well as the price of power that supposedly will rise due to this transition. Surprisingly, the AfD does also cite environmental reasons for opposing progressive energy policies. They exclusively relate to wind energy highlighting its potential harms to nature.

Transport and the future of the automobile industry is just as important in the AfD’s framing as is energy (78 codes for the category contra transformation of the transportation sector). The same line of argumentation is carried on—policies such as carbon taxes are vehemently opposed since they are harmful to the automobile industry which in return is an economically strong sector and dominant employer in Germany. E‑mobility is criticized as being costly and not affordable for the average citizen. This already somewhat indicative of an attack strategy.

The RN’s position on progressive energy policies and transportation is quite different both in terms of salience and framing. Firstly, it is striking that these topics are not very high on the agenda. Transportation was not coded at all as statements are virtually absent from the debate, and no clear perspective is evident in the entirety of the material. Their stance on progressive energy policies was coded seven times in favor and four times against it, conveying somewhat of an ambivalent position. Secondly, unlike the AfD the RN supports energy transition in terms of renewable energies such as solar energy, biogas and wood. However, overall energy policy does not feature prominently. As will be demonstrated in subsequent sections, the RN strongly promotes non-climate change related environmental measures, whereas the AfD utilizes an attack strategy in particular towards pro-climate measures. It thus appears logical that progressive energy policies are not a prominent topic for the RN but even more so for the AfD. This can also be observed concerning the respective attitudes and importance given to the strengthening of rural communities, which the RN strongly emphasizes. For the AfD, however, favorable attitudes towards strengthening rural areas were only coded a total of seven times, with six out of those seven relating to economic concerns—especially support and advancement of agricultural family businesses are emphasized. EU regulations concerning fertilizers and crop protection are also attacked because they are viewed as economically harmful. Simultaneously, banning certain products is not believed to have a positive effect on the environment; in fact, such regulations are viewed as part of an ‘environmental hysteria’. In contrast, the issue is of utmost importance to the RN, with a total of 71 codes, with 38 containing the sub code environmentalism. Their regional campaign for the postponed municipal election in March 2020 was based on the promise of strengthening ‘le localisme’, promoting the support of localism. It is the second most salient category, mostly utilized in environmentalist terms. Hervé Juvin, RN’s chief strategist, calls for an ecological civilization, promoting regional consumption and the strengthening of agriculture. Within the issue of localism, agriculture is one of the crucial topics, especially in terms of criticism regarding Macron’s supposedly missing support concerning this issue. Le Pen made environmentalism, especially localism, one of her main presidential campaign topics, pleading to leave agriculture out of free trade agreements in order to protect France’s environment. Promoting such rural development does not fit into the AfD’s attack strategy and therefore is not a strong concern. The RN, on the other hand, can capitalize on this topic, especially due to the prominent underlying notion of ‘souveraineté’. Connecting environmental issues to this broadly accepted need to conserve French culture makes the rural-communities argument a particularly strong one within the national context. A similar strategy is evident for regional environmental protection, too.

The most prominent issue is the RN’s desire to protect the (regional) environment, receiving 159 codes. In addition to their support for agriculture, Le Pen demands stricter laws for quality control of foreign produce in order to promote local re-industrialization without reduction of competitiveness due to different ecological standards within the EU. Protectionism is a recurring theme which can be understood as environmental protection but also as protection of the economy, as Le Pen demands to leave agriculture out of free trade agreements. In this context, a notion of ‘souveraineté’ is, again, often asserted, alluding to the need to protect French agricultural industries.

As for regional environmental protection, the AfD is ambivalent but the negative category opposing environmental protection outweighs the positive one (78 codes). Again, the majority of the arguments relate to the economy (48 codes). The AfD, for instance, opposes the climate action plan of the German government as well as respective EU regulations, and what has been referred to as the Green Deal. As with energy policy and transportation, these agreements are portrayed as economically extremely harmful to the citizens who bear most of the costs. This, again, conveys the AfD’s strong attack strategy concerning climate policy. In addition to economic reasons, strong anti-mainstream positions are evident within this category (8 codes). The Greens are primarily criticized given that they are the driving force behind many of the rejected initiatives. But the government is also regularly slammed, especially Angela Merkel and the CDU; they are perceived as bowing to the Greens and their agenda. On the other hand, the AfD does occasionally promote environmental protection, and even use an environmental argumentation in their opposition to windmills, which supposedly further the destruction of the national flora. Overall, 11 such instances were coded. Most of the concerns relate to the conservation of oceans as well as the reduction of plastic waste. Some of the coded segments convey notions of ‘Heimatschutz’ as well. As environmental protection generally does not fit with the attack framing, though, it is not advocated strongly. Note also that the promoted measures do not necessarily relate to climate protection as such. Less ambivalent is the congruence of anti-institutionalism codes between the two parties. This is no surprise, though, as populist parties in general take an anti-institutionalist stance.

5 Discussion

The data results in a mixed picture. Overall, the RN certainly is the more environmentally friendly party—however they largely steer clear of policies that directly combat climate change in spite of acknowledging its existence. Rather, they focus on environmental policies more broadly which can then be harnessed to promote notions of ‘souverainté’—whether those relate to cultural or economic aspects. The AfD on the other hand attacks pro-climate policy outright, particularly on the grounds of potential economic disadvantages. However, they are not necessarily hostile to all environmental measures as long as they do not interfere with the economy and do not contradict their anti-climate change stance. The results then show diverging strategies in dealing with environmental issues and which specific topics to focus on. However, some of the underlying notions appear to be rather similar. The explanation, we suspect, is at least partially the result of political opportunity structure and the nature of populism as a strategy. From this perspective, a political opportunity window opens when an issue is ideologically not clearly defined, and either not sufficiently covered or full-heartedly supported by mainstream or special interest parties. In this case, this refers to either picking up on the negative sentiments towards climate-change-action if the institutional setting allows it—e.g. the mainstream adopted green policies or a strong green party. Hence, positive connotations of environmentalism are already covered. However, in a different institutional setting it may well be beneficial to adopt a pro-environmentalist-stance—e.g. neither a strong green party nor a full-hearted support for such positions is evident among the mainstream. In this case, the RWP can swoop in and capture issues around environmentalism without contradicting, for instance, an anti-mainstream stance.

RWPs differ widely all over Europe, from their programmatic manifestos to alignments due to structural constraints of party systems. Still, the AfD is quite comparable to the French National Rally (RN) considering their political outlook (Betz and Habersack 2020, p. 112). And although European party systems show strong diversity on the one hand, they have powerful commonalities on the other (e.g. Hernández and Kriesi 2016). Examples of the latter are the rise of populist parties in the first place (Halikiopoulou 2018) or the overall salience attributed to environmental issues by many countries’ populations. However, the electoral successes of green parties and the adoption of ‘green’ policies by the political mainstream differ from country to country (Grant and Tilley 2019). Hence underlying political opportunity structures in the respective party systems are quite different while the RWPs themselves convey many similarities. This has led to the development of diverging environmental strategies.

In 2014, environmental issues did not feature prominently on the AfD’s agenda: the election program for that year’s European election contains almost no references to climate or environmental policy. It does include a somewhat suspicious attitude towards man-made climate change; however, these positions do not compare to todays. At that time, the party’s ideological core was mainly a fiscal-conservative one and the salient issues revolved around the Euro, an emphasis on economic competitiveness, the rejection of the European Union, immigration and social policy (AfD 2014). In the meantime, electoral environmentalism had become quite popular: between 2014 and 2018, the Greens were able to increase their share of voters by up to eight percentage points at the polls, reaching 25% by June of 2019 (Infratest Dimap 2020). Also, the ruling parties CDU/CSU and SPD have been in favor of policies combating climate change for a while now, but a crescendo was reached when FFF and the talk of a Green Deal was dominating news coverage in 2019. A similar development can be observed among the electorate. Environmental issues generally rank high on the population’s agenda according to a 2020 German Environment Agency survey, with 68% naming it as an important challenge (Umweltbundesamt 2020). Simultaneously, 52% of the electorate perceives FFF’s influence on policy as substantial; With 63%, an even greater share of AfD voters believe so (ARD-DeutschlandTrend 2019). From an AfD perspective, this might evoke a necessity to take sides. And with 25% of the population in favor of prioritizing the economy over climate change, at least one fourth of the population may be susceptible to the AfD’s appeal (ARD-DeutschlandTrend 2019). Among FDP and CDU voters this share increases to 37 and 29%, respectively. Additionally, only 15% of the German public supports prohibition-based approaches to environmental policy such as CO2 taxes or Diesel bans (Hofmann 2019). Thus, there clearly is strategic potential to be ceased by the AfD. Opposing pro-environmental policy is not only sensible because a positive stance on the issue is already occupied by a strong green party; there is also clearly mobilization potential for a negative framing of the topic there. Hence, it was not much of a surprise, when the AfD’s then party-leader Alexander Gauland announced that opposing the government’s climate policies will become a new priority and a central theme for the 2021 election campaign (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung 2019). This development was already foreseeable within the 2017 party manifesto, although the issues environment as well as nature and wildlife protection, consumer protection and agriculture are addressed only at the end of the 74 pages manifesto—covering 2.5 pages.

With opposition to environmental policies, the AfD is in line with the most popular strategy of RWPs: evoking a threat to the national economy and thus framing the entire issue overwhelmingly negative (Schaller and Carius 2019, p. 24). Economic reasons are by far the most frequently mentioned—especially increasing costs regarding the infrastructural changes necessary for switching from primarily coal and nuclear energy to renewables as well as the price of energy itself, and the transformation of the transport sector. This extension of the politico-economic dimension of environmental issues centers around representing ‘the people’ since citizens are thought to be the ones bearing all the costs, yet not benefitting from the changes. This is not merely a reinforcement of the idea of the ‘people vs. the elite’ but an augmentation of the ‘green-issue’ as a threat to the ‘ordinary man’ who might be forced to replace his car, oil-based central heating and maybe even pay a higher price for his steak. This also carries the notion that a Green Deal is not only a financial burden for German citizens but also for the economy as a whole. Similar economic arguments are used to justify the prolonged use of coal and nuclear energy—especially the potential loss of jobs. This non-renewable-energies stance is in line with the party’s fiscal conservative imprint, but it also appears to be a strategic extension of the party’s predominant policy orientations. An important factor is, however, also certainly the popularity of the FFF movement and its frequent media coverage. Thus, the backlash against such policies may—at least to some extent—function as a response to these developments. Another factor may however also be a delimitation concerning the Greens.

When it comes to the environment, the election program of the German Green party is quasi-inverse compared to that of the AfD. They address the same issues but offer a reverse interpretation from economics to energy, transport or food production (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen 2017, pp. 17, 35). But as the results show, this holds also true for the RN—a politically and ideologically aligned party and also a member of the AfD’s parliamentary group. This reorientation not only seems to be a strategic reaction, the AfD also created a unique selling point for itself since even the most business-friendly German party, the FDP, supports environmental protection. Hence, the AfD is the only party that combines a business-friendly stance with a rejection of pro-climate and to large extent pro-environmental policy as well.

With the AfD’s heavy stance on anti-institutionalism, it becomes clear that this position is also a reinforcement of its core to criticize the establishment and the power of the EU. The assumption that a Green Deal would take too many national competences is another coherent continuation of the party’s predominant position. Still, many attacks by party members are directed against the Greens and the governing parties, as previously stated. This is in line with the party’s overall anti-institutionalist stance.

The three factors of potential mobilization are such that (1) the structure of political opportunities offers a unique selling point and potential collective goal that is promising in regard to power relations (McAdam et al. 2011, p. 2). The representative system in particular leaves potential for opposition to mainstream and anti-environmental sentiments. The mobilization structures (2) are latent in the case of the AfD since the protest potential was stronger for FFF in Germany. However, there are opportunities for counter-protest. Polling for the AfD did remain quite similar after Gauland announced to make climate and environmental policy a priority on the party’s agenda (Infratest Dimap 2020). Still, this change in strategy does strengthen the AfD’s overall message. Collective processes of interpretation, attribution, and social construction (3) provided a chance to connect climate and environmental issues to important issues of the AfD in general. The AfD’s strategy in reaction to the surge of climate and environmental protection is not only an extension of the RWP-position with an anti-climate stance, it is an amplification of the idea of assuming a truly representative function regarding the people because the AfD supposedly protects them from unnecessary costs and further harm to the economy. In this regard, the automobile industry and the energy sector are definitively relevant for the AfD’s policy positions since they are also large employers in Germany—thus also the greater importance of ‘old’ fossil industries. The connectedness to potentially economically harmful EU regulations regarding the environment is strongly tied to fear of economic harm.

As for France and the RN, the Europe Écologie—Les Verts (EELV) did not fare well in the 2017 elections, leaving a very weak Green party with only one seat in the national legislature and no candidate for the presidency. Although each party included environmental protection in their party programs, there were hardly any clear positions. While Jean-Luc Melenchon (La France insoumise) was the only candidate who really addressed environmental protection, public debates about environmentalism were less prominent. Le Pen raised the issue in her 144-points-program, mainly referring to stricter laws in order to protect French agriculture, thereby alluding to localism (Le Pen 2017).

RN’s electoral strategy in the 2019 European elections was successful, reaching a 23.42% share of the vote and surpassing Macron’s coalition. But France’s Green Party also was successful with a 13.47% share of votes, indicating an increasing salience of environmental issues. However, they were not able to maintain their success and currently, polls for the EELV range between six and nine percent (Politico 2020). This new discourse on environmentalism will most likely strongly affect the presidential election in 2022, and with a growing demand for green policies French parties are adjusting their strategies. Due to the two-round system for presidential and legislative elections, the EELV faces disadvantages as opposed to the RN, as the systemic predispositions in France will favor the RN. Sometimes, Le Pen polls only slightly behind Macron, one or two percent at the most (Politico 2020). The founder of the RN’s predecessor, Front National, Jean-Marie Le Pen, ignored environmental policies and viewed ecology as an interest of urban bohemians. He may have a point, suggesting that the urban-green-clientele is not be interested in voting for the FN (now RN). But the movement around José BovéFootnote 5 combines environmentalism with anti-free trade and anti-establishment beliefs—this might also appeal to the group of voters that Marine Le Pen now aims for.

By portraying the RN as the only true defender of an ‘ecological civilization’ (Le Pen 2019), Le Pen not only emphasizes environmental protection, she also ties this to the idea of France First in order to create sustainability through adequate policies and the abandonment of some trade agreements. This is an extension of its protectionist-orientation. An outcome of this strategy appears to be that, unlike the majority of the RWPs, the RN portrays itself as a strong advocate for environmentalism—through conveniently leaving climate change out of the equation. The promotion of regional consumption and production of goods can be understood as a search for a common ecological standard within the EU, represented in their demand to exclude competition that does not adhere to the same regulations. But still, Le Pen’s environmentalism is another version of her anti-free trade and protectionist stance.

Furthermore, the protectionist orientation of the RN merges with their belief in French ‘souveraineté’ which does not only consist of protecting France’s nature and economy but also its culture. One of this strategy’s prime examples is the city of Hénin-Beaumont, where the RN has been governing since 2014 with its “own brand of down-to-earth environmentalism” (Onishi 2019). In Hénin-Beaumont, sheep graze public fields, all lamps have been changed to environmentally friendly LEDs and the city plants trees free of charge. In this way RN manages to include environmentalism in a way conducive to their agenda with a strong potential for resonance due to the generally high support for these protectionist stances among the electorate. At the same time, this is an attempt to counter Macron’s supposedly missing support for French agriculture. There is generally a strong connection to its anti-establishment stance, especially when criticizing the French government as well as the EU for their alleged hypocrisy concerning environmentalism. The ‘elite against the citizens’ dichotomy aligns with the center-periphery cleavage in the French case where the centralism of Paris has been a long-standing conflict.

Adapting environmentalism appears to be promising given the issue’s salience: Ecology was named the number one priority among French voters (Ipsos/Sopra Steria 2019). The reasons named are increasing heat waves, sudden temperature fluctuations throughout the year, urban air pollution and loss of biodiversity, among others (Le Monde 2019). Accordingly, 69% of French citizens are pessimistic about the future of the planet, and 72% say they have increased their interest in environmental issues in 2019. Also 57% expressed doubts about the sincerity of Macron’s commitment to the environment (Harris Interactive 2019). The criticism of the RN concerning environmental policies is therefore in line with what a majority of French people believe.

The three factors of potential mobilization regarding the RN are that (1) the political opportunity structures offer potential resonance with an adaption of environmental issues given that the establishment faces strong criticism around this topic, and the EELV is quite weak while environmentalism is extremely salient for the public. The mobilization structures (2) are also promising due to the yellow vests’ criticism of the government and to a lesser degree FFF as well as society generally raising the importance of the issue. The collective processes of interpretation, attribution, and social construction (3) provide the opportunity to connect environmentalism with other important RN policies. In return, the party is able to extend its belief of French ‘souveraineté’ and localism to a pro-environmentalist stance. In doing so, RN merged the idea that free trade, especially concerning food, is a threat for France and French culture, and protecting the environment is in return a duty in order to preserve the country.

6 Conclusion

Right-wing-populism seems to be much more flexible regarding climate and environmental policies than previously anticipated, particularly in terms of strategies used to harness these issues for the benefit of the respective party. As was demonstrated, these strategies can be considered to be—at least partially—a product of underlying political opportunity structures. Party strategies are certainly not only reactions to the conditions of political competition. Taking this into account, the idea that ideology is not important for populism cannot be rejected given that both stances on climate-change and environmentalism are path-dependent. But we can also see that many political opportunity structures are in line with the party’s chosen path. In this context, our study is limited because the national political context in which these parties perform are different. Apart from the different structure of the economy, the different policy beliefs of RN and AfD due to the fiscal-conservative imprint of the AfD also make a difference. These alternative factors need to be assessed further. However, the results are still intriguing as we convey that the strength of the Greens, the structure of electoral systems and especially societal changes do have a strong impact on party behavior. We convey that there are different POS at play, both systemically and party-wise. Especially the status of green parties in the respective party system, the party system itself, the representation of environmental issues by the government and mainstream parties as well as public salience of the issue are likely to be predetermining factors for RWPs.

Although we do not deny a sincere motivation for each alignment, POS and the changes in party alignments suggest at least a strategic advantage in both cases. In the case of the RN, the extension of the RWP-position to a pro-climate stance is coupled with integrating the idea that free trade, especially in terms of food, is a threat to the French nation and culture. The AfD’s reaction to the surge of environmental protection is an extension of the already existing position with a much stronger focus on anti-climate-action. Stressing the importance of this previously marginalized issue offers the opportunity to assert the AfD’s claim to be the peoples’ only representative that offers protection from transitional costs and from harm to the economy generally. The AfD thereby strengthened its fiscal-conservative stance whereas the RN chose to rather stress the belief of regionalism, protectionism and ‘Heimatschutz’. These re-alignments do appear to be strategically motivated as the adoption of green policies may deliver an electoral advantage to the RN in the winner-takes-all system. The German party system with its representative structure leaves much more room for an RWP to oppose green policies, especially with a strong green party whose clientele is also both rather leftist and pro-migration. This demonstrates that right-wing-populism is quite adaptable in terms of strategies concerning environmentalism.

Future research will have to determine whether the alignment to green policies and the extension of the party position creates resonance with a new clientele. Put differently: Do these strategies pay off? Larger studies should also establish which alignments other European countries may enter into in the future, thereby investigating if left/right and pro/contra environmentalism positions are transforming into a cross-cutting cleavage in Europe.

Notes

We analyzed speeches from the main spokespeople of the respective parties. This includes Alice Weidel and Jörg Meuthen from the AfD, and Marine Le Pen from RN.

For the years of 2019 and 2020, a majority of the documents were Tweets opposed to speeches.

As explained in Table 1.

The quantitative part is of purely indicative value since we did not calculate reliability using ICR statistics.

Joseph (José) Bové is a farmer, politician for the EELV, and member of the alter-globalization movement.

References

AfD. 2014. Mut zu Deutschland. Für ein Europa der Vielfalt. AfD-Cottbus.de. https://www.afd-cottbus.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/AfD-Europaprogramm_Langfassung.pdf. Accessed 30 May 2020.

ARD. ARD-DeutschlandTrend. September 20, 2019. Klima toppt Wirtschaft. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/deutschlandtrend-1749.html (Created 1 Aug 2019). Accessed 30 May 2020.

Arzheimer, Karl, and Elisabeth Carter. 2006. Political opportunity structures and right-wing extremist party success. European Journal of Political Research 45(3):419–443.

Aslanidis, Paris. 2016. Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies 64(1):88–104.

Barr, Robert R. 2017. The resurgence of populism in latin America. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Barr, Robert R. 2019. Populism as a political strategy. In Routledge handbook of global populism, ed. Carlos de la Torre, 44–56. London, New York: Routledge.

Benoit, W. L., & Holbert, R. L. (2008). Empirical intersections in communication research: Replication, multiple quantitative methods, and bridging the quantitative-qualitative divide. Journal of Communication 58(4):615–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00404.x

Betz, Hans-Georg, and Fabian Habersack. 2020. Regional nativism in East Germany: the case of the AfD. In The people and the nation: populism and ethno-territorial politics in europe, ed. R. Heinisch, E. Massetti, and O. Mazzoleni, 110–134. London: Routledge.

Bornschier, Simon. 2012. Why a right-wing populist party emerged in France but not in Germany: cleavages and actors in the formation of a new cultural divide. European Political Science Review 4:121–145.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen. 2017. Bundestagswahlprogramm. Gruene.de. https://cms.gruene.de/uploads/documents/BUENDNIS_90_DIE_GRUENEN_Bundestagswahlprogramm_2017_barrierefrei.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2020.

Conley, Hazel, and Edmund Heery. 2007. Frame extension in a mature social movement: British trade unions and part-time work, 1967–2002. Journal of Industrial Relations 49:5–29.

Craiutu, Aurelian. 1999. Tocqueville and the political thought of the french doctrinaires (Guizot, Royer-collard, Remusat). History of Political Thought 20(3):456–493.

Flick, Uwe. 2008. Triangulation. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: VS.

Forchtner, Bernhard, and Christoffer Kølvraa. 2015. The nature of nationalism: populist radical right parties on countryside and climate. Nature and Culture 10(2):199–224.

Forchtner, Bernhard, Andreas Kroneder, and David Wetzel. 2018. Being skeptical? Exploring far-right climate-change communication in Germany. Environmental Communication 12:589–604.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. 2019. Gauland erklärt Kampf gegen Klimaschutzpolitik zum Hauptthema. FAZ.de. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/afd-will-kampf-gegen-klimaschutz-zum-hauptthema-machen-16408499.html (Created 29 Sept 2019). Accessed 30 May 2020.

Giugni, Marco. 2011. Political opportunity: still a useful concept? In Contention and trust in cities and states, ed. M. Hanagan, C. Tilly. Dordrecht: Springer.

Grant, Zack P., and James Tilley. 2019. Fertile soil: explaining variation in the success of Green parties. West European Politics 42:495–516.

Halikiopoulou, Daphne. 2018. A right-wing populist momentum? A review of 2017 elections across Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies 56:63–73.

Hernández, Enrique, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2016. The electoral consequences of the financial and economic crisis in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 55(2):203–224.

Hofmann, Frederieke. 2019. Klimaschutz – nur 15 % für Verbote. ARD. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/deutschlandtrend-1749.html (Created 1 Aug 2019). Accessed 30 May 2020.

Infratest Dimap. 2020. Sonntagsfrage bundesweit vom 17. Mai 2014–15. Mai 2020. https://www.infratest-dimap.de/umfragen-analysen/bundesweit/sonntagsfrage/. Accessed 30 May 2020.

Interactive, Harris. 2019. Les Français et l’écologie. Paris: Métropole Télévision.

Ipsos, Sopra Steria. 2019. Fractures Françaises 2019. Paris: Le Monde, la Fondation Jean Jaurès and l’Institut Montaigne.

Jagers, Jan, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2007. Populism as political communication style: an empirical study of political parties’ discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research 46(3):319–345.

Jansen, Robert S. 2011. Populist mobilization: a new theoretical approach to populism. Sociological Theory 29(2):75–96.

Judis, John B. 2016. The populist explosion: how the great recession transformed American and European politics. New York: Columbia Global Reports.

Kestilä, Elina, and Peter Söderlund. 2007. Subnational political opportunity structures and the success of the radical right: evidence from the March 2004 regional elections in France. European Journal of Political Research 46(6):773–796.

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1986. Political opportunity structures and political protest: anti-nuclear movements in four democracies. British Journal of Political Science 16(1):57–85.

Koopmans, Ruud, and Jasper Muis. 2009. The rise of right-wing populist Pim Fortuyn in the Netherlands: a discursive opportunity approach. European Journal of Political Research 48(5):642–664.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Ruud Koopmans, Jan W. Duyvendak, and Marco G. Guigni. 1992. New social movements and political opportunities in western Europe. European Journal of Political Research 22:219–244.

Kriesi, Hanspeter, Ruud Koopmans, Jan W. Duyvendak, and Marco G. Giugni. 1995. New Social Movements in Western Europe: a comparative analysis. London: UCL Press.

Kuckartz, Udo. 2018. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung, 4th edn., Weinheim: Beltz Juventa.

Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. Populism: what’s in a name? In Populism and the mirror of democracy, ed. F. Panizza, 32–49. London: Verso.

Le Monde. 2019. L’écologie, une préoccupation désormais majeure pour les Français. LeMonde.fr. https://www.lemonde.fr/politique/article/2019/09/16/l-ecologie-une-preoccupation-desormais-majeure-pour-les-francais_5510924_823448.html (Created 16 Sept 2019). Accessed 7 May 2020.

Le Pen, Marine. 2017. 144 Engagements Présidentiels. Paris: Rassemblement National.

Le Pen, Marine. 2019. Fréjus – Discours de Marine Le Pen. RassemblementNational.fr. https://rassemblementnational.fr/videos/frejus-discours-de-marine-le-pen/. Accessed 15 Feb 2020.

Politico. 2020. Polls of Polls. Politico.eu. https://www.politico.eu/europe-poll-of-polls/france/. Accessed 28 Mar 2020.

Löblich, Maria. 2014. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse von Medienframes. Kategoriengeleitetes Vorgehen am Beispiel der Presseberichterstattung über den 12. Rundfunkänderungsstaatsvertrag. In Framing als politischer Prozess. Beiträge zum Deutungskampf in der politischen Kommunikation, ed. F. Marcinkowski, 63–76. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Lockwood, Matthew. 2018. Right-wing populism and the climate change agenda: exploring the linkages. Environmental Politics 27(4):712–732.

Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen. 2018. Frankreich. Wirtschaft, Gesellschaft,Politik, Kultur, Mentalitäten. Stuttgart: Springer.

Marks, Gary, and Doug McAdam. 1996. Social movements and the changing structure of political opportunity in the European Union. West European Politics 19:249–278.

McAdam, Doug, John D. McCarthy, and N. Zald Mayer. 2011. Introduction: opportunities mobilizing structures and framing processes—toward a synthetic, comparative perspective on social movements. In Comparative perspectives on social movements, ed. D. McAdam, J.D. McCarthy, and M. Zald, 1–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, James. 2019. Authoritarianism, populism, and the environment: comparative experiences, insights, and perspectives. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109(2):301–313.

Mény, Yves, and Yves Surel. 2002. The constitutive ambiguity of populism. In Democracies and the populist challenge, ed. Y. Mény, Y. Surel, 1–21. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Meyer, David, and Debra Minkoff. 2004. Conceptualizing political opportunity. Social Forces 82(4):1457–1492.

Moffitt, Benjamin, and Simon Tormey. 2014. Rethinking populism: politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies 62(2):381–397.

Mudde, Cas. 2004. The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39(4):542–563.

Olwig, Kenneth. 2003. Natives and aliens in the national landscape. Landscape Research 28(1):61–74.

Onishi, Norimitsu. 2019. France’s far right wants to be an environmental party, too. The New York Times. www.nytimes.com/2019/10/17/world/europe/france-far-right-environment.html. (Created 17 Oct 2019). Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Oswald, Michael. 2020. Strategisches Framing. Eine Einführung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Raschke, Joachim, and Ralf Tils. 2007. Politische Strategie. Eine Grundlegung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Akkerman Tjitske. 2017. Flank attacks: populism and left-right radicalism in western Europe. Party Politics 23(3):193–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815596514.

Rucht, Dieter. 1996. The impact of national contexts on social movement structures: a cross-movement and cross-national perspective. In Comparative perspectives on social movements, ed. D. McAdam, J. McCarthy, and Z. Mayer Zald, 185–204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rydgren, Jens. 2004. Explaining the emergence of radical right-wing populist parties: the case of Denmark. West European Politics 27(3):474–502.

Rydgren, Jens. 2010. Radical right-wing populism in Denmark and Sweden: explaining party system change and stability. SAIS Review 30(1):57–71.

Schaller, Stella, and Alexander Carius. 2019. Convenient Truths. Mapping climate agendas of right-wing populist parties in Europe. Berlin: adelphi.

Scheufele, Bertram T., and Dietram A. Scheufele. 2012. Framing and priming effects. In International companions to media studies The International Encyclopedia of Media Studies, Vol. V, ed. Erica Scharrer, 89–107. Malden: Blackwell.

Schreier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

da Silva, Filipe, and Mónica Vieira. 2019. Populism as a logic of political action. European Journal of Social Theory 22(4):497–512.

Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford. 1988. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Resolution 1:197–218.

Snow, David A., E. Burke Rochford, Steven K. Worden, and Robert D. Benford. 1986. Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review 51(4):464–481.

Spies, Dennis, and Simon T. Franzmann. 2011. A two-dimensional approach to the political opportunity structure of extreme right parties in western europe. West European Politics 34(5):1044–1069.

Stanley, Ben. 2008. The thin ideology of populism. Journal of Political Ideologies 13(1):95–110.

Taggart, Paul. 2000. Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Taggart, Paul. 2017. Populism in western Europe. In The oxford handbook of populism, ed. C.R. Kaltwasser, P. Taggart, P. Ochoa Espejo, and P. Ostiguy, 248–264. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Umweltbundesamt. 2020. Umweltbewusstsein und Umweltverhalten. Umweltbundesamt.de. https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/daten/private-haushalte-konsum/umweltbewusstsein-umweltverhalten#das-umweltbewusstsein-in-deutschland (Created 19 Feb 2020). Accessed 30 May 2020.

Weyland, Kurt. 2001. Clarifying a contested concept: populism in the study of latin American politics. Comparative Politics 34(1):1–22.

Funding

No funding for this research was received.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.T. Oswald, M. Fromm and E. Broda declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Oswald, M.T., Fromm, M. & Broda, E. Strategic clustering in right-wing-populism? ‘Green policies’ in Germany and France. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 15, 185–205 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-021-00485-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-021-00485-6