Abstract

Meanings of democracy are far more complex than results of standardized survey research imply. They are diverse and intertwined with other individual concepts and subjective experiences. In terms of phenomenological adequacy, they are important first order constructions that can be used for building second order typologies and explanations for political action. Survey-based quantitative research has clear limits in terms of gathering such first order constructions, even if one wants to integrate them. Drawing from a phenomenological perspective of methodology and experience from 389 qualitative interviews conducted in the state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany, we argue that research on meanings of democracy might rather use open, qualitative assessments and consider four methodological aspects. First, we need to have a theoretical and methodological basis for analyzing “everyday philosophies” and root our concepts in these first order constructions. Phenomenology and the concept of lifeworld offer such a guideline. Second, we should not oversimplify analysis. People differ greatly in how they define democracy, and this should be reflected in research. Third, we advocate a qualitative multi-dimensional analysis that separates democracy, politics and actual use of democracy. This can be used to develop a typology of individual, but collectively shared, political lifeworlds. Finally, we argue that insights from this kind of research could be used to compliment standard survey instruments and contribute to developing and frequently testing a comprehensive instrument to assess the meanings of democracy in a more holistic way and to control our scientific second-order constructions of democracy.

Zusammenfassung

Die Bedeutungen von Demokratie sind weitaus komplexer als die Ergebnisse standardisierter Umfrageforschung vermuten lassen. Sie sind vielfältig und mit anderen individuellen Konzepten und subjektiven Erfahrungen verflochten. Im Hinblick auf die phänomenologische Angemessenheit sind sie wichtige Konstruktionen erster Ordnung, die für den Aufbau von Typologien zweiter Ordnung und Erklärungen politischen Handelns genutzt werden können. Umfragebasierte quantitative Forschung hat klare Grenzen hinsichtlich der Erfassung solcher Konstruktionen erster Ordnung. Ausgehend von einer phänomenologischen Perspektive und den Erfahrungen aus 389 qualitativen Interviews, die im Bundesland Baden-Württemberg durchgeführt wurden, argumentieren wir, dass die Forschung zu Bedeutungen von Demokratie auch offene, qualitative Bewertungen verwenden und dabei vier methodologische Aspekte berücksichtigen sollte. Erstens brauchen wir eine theoretische und methodologische Grundlage für die Analyse von „Alltagsphilosophien“ und müssen unsere Konzepte in diesen Konstruktionen erster Ordnung verwurzeln. Phänomenologie und das Konzept der Lebenswelt bieten einen solchen Leitfaden. Zweitens sollten wir die Analyse nicht zu sehr vereinfachen. Die Menschen unterscheiden sich sehr darin, wie sie Demokratie definieren, und dies sollte sich in der Forschung widerspiegeln. Drittens plädieren wir für eine qualitative mehrdimensionale Analyse, die Demokratie, Politik und die tatsächliche Nutzung von Demokratie voneinander trennt. Daraus lässt sich eine Typologie individueller, aber kollektiv geteilter politischer Lebenswelten entwickeln. Schließlich argumentieren wir, dass die Erkenntnisse aus dieser Art von Forschung genutzt werden könnten, um Standardinstrumente für Umfragen zu ergänzen und zur Entwicklung und häufigen Erprobung eines umfassenden Instruments beizutragen, mit dem die Bedeutungen von Demokratie ganzheitlicher bewertet und wissenschaftliche Konzepte von Demokratie zweiter Ordnung kontrolliert werden können.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sidney Verba, one of the doyens of political culture and survey research, argues that “an individual’s beliefs and values relevant to democracy are hard to elicit. They would be revealed only across a range of choice situations, observed over time, in varying contexts. Surveys, with their simple questions asked uniformly of a sample, run the danger of oversimplifying what is there, missing the main points, and perhaps creating rather than recording the reality we are studying.” (Verba 2000, p. 238) Why is that? First, democracy is an essentially contested concept in political science (cf. Bollen 1990; Collier et al. 2006; Coppedge 2012; Gallie 1956). There are numerous, sometimes competing scientific definitions of what democracy actually is. For example, Collier and Levitsky (1997, p. 431) find “hundreds” of different democracies with adjectives, i.e. subtypes of democracy designated by adjectives. And Jean-Paul Gagnon (2018) is even counting a total 2234 descriptors of democracy. These numbers alone call into question whether democracy is a universal value (cf. Andersen et al. 2018, p. 5). Even though there may be a root concept of democracy, which, as Munck and Verkuilen (2002) suggest, includes contestation and participation, there are broad variations that include further attributes and may even question this core definition (cf. McKeon 1951; Naess 1956; Christophersen 1966). For example, Coppedge et al. (2011, p. 253 ff.) elaborate six different concepts of democracy that emphasize different regimes and thus require different institutions and address different questions: electoral, liberal, majoritarian, participatory, deliberative and egalitarian conceptions of democracy. Second, these different conceptions are translated into different variables for measuring democracy, regardless of whether they are used to measure the existence of democracy or to measure people’s consent to these conceptions of democracy (Munck and Verkuilen 2002; Coppedge et al. 2011; Ariely 2015; Shin and Kim 2018). Third, instruments like those developed by the V‑Dem Project using the six concepts of Coppedge et al. (2011) measure democracy almost exclusively on the mnational level and ignore sub-national or associative levels (Gagnon and Fleuss 2020). Consequently, for survey-based research on public opinion, this means that the measurement of people’s attitudes and opinions depends on the instrument used. This implies that rather the approval or rejection of the definitions of democracy given by the researchers is recorded than the people’s original ideas and meanings of democracy (Canache 12,13,a, b; Canache et al. 2001; Schaffer 2014).

If we now assume that these subjective meanings of democracy are central to how people act politically, how satisfied they are with their polity and, as a consequence, how stable their political system is (Almond and Verba 1963; Easton 1965, 1975; Dalton and Klingemann 2007; Verba 2000), then it is all the more important to find appropriate ways to adequately capture these subjective meanings in their own right.

In the wake of Verba, we argue that standardized surveys are unable to capture the various subjective meanings of democracy. And even though there are attempts to enrich surveys with open-ended questions (e.g. Dalton et al. 2007; Bratton 2010; Canache 12,13,a, b), they still are limited in capturing the complexity of meanings of democracy (Schaffer 2014). This poses theoretical, methodological and empirical problems. One theoretical challenge is that individual meanings of democracy are “bounded concepts”. These are deeply rooted in the experiences of individuals and do not necessarily reflect scientific or “objective” notions of democracy (see Schaffer 2014). The methodological problem linked with this is that closed, standardized questionnaires only offer certain elements or definitions of democracy from which the respondents can choose or on which they can give ratings. In this way, the researchers draw the respondents’ attention to certain meanings and initiate processes of priming, social desirability and evaluation. Thus, different methodological approaches are needed. Last but not least, there are practical problems. If public opinion research is unable to register peculiarities and deviations from its own definitions and perspectives, it could run the risk of failing to capture reasons for important social issues and developments, such as populism, distrust and discontent in democracy and democratic institutions.

In the following article, we will therefore elaborate on political culture and developments in the field of measuring meanings of democracy. Using the results of 389 qualitative interviews—conducted in two studies in the German State of Baden-Wuerttemberg in 2014 and 2017—to illustrate our argument, we suggest that research on the meaning of democracy should consider four important methodological aspects beyond survey research:

-

1.

Open up: when we use open questions in surveys or qualitative interview methods, we need a theoretical and methodological basis for how people construct their own basic concepts or “everyday philosophies”. Here phenomenology offers fundamental theoretical and methodological considerations. From a Schützian phenomenological perspective and against the background of our studies, we argue that more differentiated instruments for capturing meanings of democracy in large-n studies can only be derived from open qualitative studies. Since individual meanings of democracy are deeply rooted in people’s everyday experiences, meanings sometimes differ fundamentally between individuals and their political lifeworlds (cf. Schütz and Luckmann 2003).

-

2.

Divide: simply asking about the meaning of democracy can lead to a strong simplification, since people often create complex cross-references and networks to other topics (cf. Schaffer 2014) and thus weave a dense web of meanings. This should be reflected in a study but can only be implemented to a limited extent in surveys. Political lifeworlds are the political “world at hand” of people. As our research shows, people differ greatly in how they define democracy, politics, participation, and community. Nevertheless, these definitions and meanings and their links can be used to group people with similar characteristics.

-

3.

Typologize: we therefore advocate a qualitative multi-dimensional analysis, in which democracy, politics, and political action are analyzed separately, but have to be integrated in order to have a fuller picture. This reflects the idea of democracy as a bounded concept and in addition allows for developing a typology of individually socialized, but collectively shared political lifeworlds. In our studies, we analyzed meanings of democracy, political attitudes, and everyday life experiences in order to identify political lifeworlds (understood as bounded concepts of meaning and acting).

-

4.

Assess: We argue that insights from this kind of research could be used to complement standard survey instruments and contribute to developing and frequently testing a comprehensive instrument to assess the variety of meanings of democracy in a more holistic way. The methodology we propose then can be used in any bounded space, any political level, and cultural context.

1 Political culture and (the importance of) meanings of democracy

Political systems, their institutions, and stability are inextricably intertwined with public opinion and political culture of the respective community (Almond and Verba 1963). The concept of political culture assumes that “a political regime that wants to remain persistent in the long run, requires a political culture that is in congruency with the institutional structure” (Fuchs 2007, p. 163) and that the political culture of a country is shaped by the attitudes of its citizens. Building on Easton (1965, 1975), Fuchs (2007, p. 165 f) further distinguishes between objects of a political system and the respective attitudes of the people towards these objects. At the value level, people’s attitudes towards basic democratic values are crucial for the persistence of a democratic system, whereas at the structural level the support of a democratic regime is the core element of persistence. If we accept the basic assumption of Almond and Verba (1963) and others, “that democracy was based on a supportive public that endorsed a democratic system even in times of tumult” (Dalton and Klingemann 2007, p. 8), one aspect of political culture seems to be crucial: What do people understand democracy to mean? If people are to support a democracy, their evaluation and level of support strongly depend firstly on what they consider a democracy to be, and secondly on the comparison of this subjective definition with what they experience as the “real world democracy” at work in their political system. Interestingly, support of democracy seems to be more or less independent from the “objective” status of a polity as democratic or authoritarian. Several studies show that there is also mass support for democracy in authoritarian countries (cf. Dalton and Shin 2006; Shin and Kim 2018), which can be explained by broadly differing understandings of what democracy is and where it exists (cf. Schaffer 2014). This is closely linked with the problem of instrumentalizing the term democracy. As a contested concept, democracy can serve as an empty signifier for various political purposes. On the one hand, autocrats like Putin with his narrative of “sovereign democracy” and semi-autocrats like Viktor Orban pointing at his “illiberal democracy” offer alternative understandings of democracy that barely hide their depreciation of principles associated with democracy, such as equal representation and equality, separation of powers, or the bindingness of human rights and rule of law. On the other hand, especially in Europe, but also in the US and other political systems classified as democratic, polities face populist contestation from within (Mudde and Kaltwasser 2012, 2013; Taggart 2004; Weyland 1999). Especially right-wing populist parties, movements and their supporters exhibit more or less open authoritarian tendencies and thus can be considered as a threat to democracy. But still they often claim to protect democracy as they allege to defend and articulate the will of the people against detached elites and often strive to establish more direct-democratic institutions (Canovan 1999). Moreover, they seem to “challenge our understanding of democracy” in a profound way, as they “see themselves as true democrats, voicing popular grievances and opinions systematically ignored” and “their professed aim is to cash in democracy’s promise of power to the people” (Canovan 1999, p. 2). Arguments like this suggest that subjective meanings of democracy and evaluations of its successful or failed implementation by the existing (democratic) political system may be one of the driving forces behind successful populist mobilization.

We also witness another development in contemporary democracies that may be rooted in different understandings of democracy. While conventional or traditional forms of political participation—like participating in elections or party membership—decrease, “new forms of engagement and participation expand political participation beyond the boundaries of what it was conventionally viewed to be” (Dalton and Klingemann 2007, p. 15; Theocharis and van Deth 2018). Therefore, shifts in political participation might be an expression of varying lifestyle-politics (De Moor 2017) or different political lifeworlds (Frankenberger and Buhr 2017; Frankenberger et al. 2015) rather than of a de-democratization.

These few examples highlight the importance of assessing individual, subjective meanings of democracy. They serve as a basis for the evaluation of polity, politics, and policies. The respective questions to be asked then are: What does democracy mean to everyday people? A more basic, and genuinely methodological question also arises: How are meanings of democracy measured and are these measurements adequate for capturing differences?

2 Researching meanings of democracy

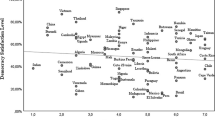

There is a broad literature and empirical research on political culture and democracy. Starting with Almond and Verba’s groundbreaking work on civic culture (1963), an increasingly differentiated field of research has developed. Due to methodological developments in survey research and its intensive use, almost all societies of the world are now being studied, regardless of whether they are democratic or not. Today, surveys such as the World Value Survey, the International Social Survey Project, regional surveys such as the Afrobarometer, the Eurobarometer, the European Value Study, or the Latinobarometro, as well as countless national and local studies produce a huge database for political culture and democracy research. These studies usually use rigorous quantitative methods, including closed questionnaires with standardized items, and thus offer many opportunities for cross-national and regional comparisons. To investigate the degree of support for democracy, they apply different strategies. In some studies, close-ended questions are used to directly inquire about support for democratic rule. In others, the respondents are asked to evaluate elements of democracy and autocracy and from the response patterns, types of support and understanding of democracy are deduced. In a few surveys, open-ended questions are also asked about the importance of democracy. For example, Ronald Inglehart (2003, p. 54) uses a democracy/autocracy index consisting of four items to measure support for democracy and another nine variable items to measure respondents’ ratings of predefined characteristics of democracyFootnote 1. Most surveys use similar strategies to measure the understanding of democracy. For this purpose, taxonomies have been developed to measure “substantive distinctiveness in democratic understanding” (Shin and Kim 2018, p. 229). For example Lu (2013) offers a procedure-based liberal and a substance based “minben” conception of democracy; Fuchs (1999) uses the three categories libertarian, liberal, and socialist; Dalton et al. (2007) employ political freedom, political process, and social benefits as categories; Canache (2012) distinguishes liberty and freedom, political equality, participation, rule of law, economic and social outcomes, negative meaning; and Ferrín and Kriesi (2016) use electoral, liberal, social, direct, inclusive, and representative concepts of democracy as categories. Even though these categories are usually linked to sets of items in surveys that allow for a more detailed analysis of individual meanings of democracy, they still are rooted in the researchers’ ideas about democracy. And the vaguer the formulations for capturing democracy are, the more they allow “different and even controversial meanings to be ascribed to the concept. Some empirical evidence suggests that explicit support for democracy does not reflect a common understanding of the concept of democracy” (Ariely 2015, p. 624; cf. Schedler and Sarsfield 2007; Jamal and Tessler 2008).

To compensate for these weaknesses of purely quantitative studies and to capture subjective meanings of democracy more precisely, some surveys also use open-ended questions (e.g. Bratton et al. 2005; Dalton et al. 2007; Diamond and Plattner 2008; Canache 12,13,a, b; Canache et al. 2001; Shi 2009; Shin and Kim 2018). The resulting data highlights some of the methodological problems of survey studies and can show that open questions offer significant improvements in drawing the full picture of subjective meanings of democracy. At the same time, however, the use of open-ended questions raises further methodological questions. Canache (2012, p. 1134) argues that we can understand subjective meanings of democracy only if we consider its content and complexity. For we cannot take it for granted that theoretical considerations and concepts of democracy are consistent with life-world meanings of democracy (Canache 2012, p. 1136; Dalton et al. 2007). Using open questions as control variables in surveys, Canache et al. (2012, p. 518) show that the meanings of democracy do not only refer to political areas, but also include economic, political-institutional, and social issues. For example, in studies on Romania and El Salvador, more than 50% of the respondents stated that they associate social and/or economic aspects with democracy. As an effect, “cross-national comparison risks producing misleading results when analysis focuses on data that represent different things in different places” (Canache et al. 2012, p. 524). In another analysis of survey data, Canache (2012, p. 1149) shows that “structure and content of democratic conceptualizations vastly matter for citizens’ attitudes and patterns of political participation”.

But even the use of open-ended questions in surveys is methodologically problematic and can lead to distorted images of subjective meanings of democracy, as Schaffer (2014) argues. Using qualitative and quantitative data on meanings of democracy in the Philippines, he shows that the findings from open-ended survey questions are also inappropriate for capturing subjective meanings of democracy, because “Compression, compartmentalization, and homogenization may strike the reader as necessary concessions that one must make to generate data on meanings of democracy that are globally comparable. The combined effect of these three problems, however, calls into question the value of such data” (Schaffer 2014, p. 326). In his view, the findings of global convergence in the meaning and assessment of democracy are the result of certain measurement and evaluation strategies. Bratton (2010) makes a similar point when he says that “we do not know whether all survey respondents conceive of freedom in the same way … Thus it seems presumptuous to base the comparative study of public attitudes about democracy on the assumption that all people understand democracy simply as freedom” (Bratton 2010, p. 107). Schaffer therefore argues that instead there is a wide range of very complex and multidimensional meanings of democracy that influence the evaluation of politics: “The multivalence, puzzlement, ambivalence, and contradiction that characterize how people understand such terms can be gainfully explored only by providing people expansive opportunities to express their thoughts, and to reflect on the complexity of what they are saying” (Schaffer 2014, p. 328). In order to grasp this complexity, qualitative methods are needed that allow the interviewees to produce “thick descriptions” of their individual meanings of democracy.

Apart from Schaffer’s work on meanings of democracy in Senegal (Schaffer 2000) and the Philippines (Schaffer 2014), there are comparatively few studies on local meanings of democracy that use interpretative or ethnographic methods and tools. These include studies on meanings of democracy in the Arab World (Browers 2006), Russia (Carnaghan 2011), and the Buganda region in Uganda (Karlström 1996). All these studies are based on variants of qualitative interviews for data collection and interpretative-inductive phenomenological, hermeneutic, or discourse-analytical procedures for data analysis. They reveal a variety of meanings of democracy among the interviewees. These meanings often differ greatly in complexity, dimensionality, and content. As Schaffer (2014) says, these findings have an impact on the plausibility and validity of the findings of standardized and internationally comparative surveys, which are unable to reflect this complexity or even to capture it. However, the studies differ with respect to the degree of systematization of the findings and the requirements to create taxonomies for further research. The latter is particularly systematic in studies that use the Q‑methodologyFootnote 2, such as the studies on the USA by Dryzek and Berejikian (1993), 13 post-communist states in Europe (Dryzek and Holmes 2002), or Estonia (Andersen et al. 2018). Andersen et al. (2018) analyze differences between defined and lived democracy. Their work showed that there are three different discourses on democracy in Estonia: “a libertarian democracy as freedom; a participatory democracy as empowerment; and a populist democracy as the utopia of good policies” (Andersen et al. 2018, p. 4). They use focus group interviews from which they derive statements about democracy, which are then evaluated by the respondents in a Q-Methodology Survey. They emphasize the inductive character and reliability as particular advantages of their method, which allows to aggregate individual meanings of democracy into discourses without reducing their complex nature. They argue that “conventional quantitative and qualitative methods (…) allow limited scope for surprise. Whether implicitly or explicitly, they inevitably rely on prior concepts as guides in specifying the empirical input and as points of reference when interpreting the analytical output” (Andersen et al. 2018, p. 16).

Even though we see the strengths of this approach, we do not agree with this last assessment. We claim that narrative interviews and hermeneutic evaluation methods can very well discover new and surprising results and that even the findings, despite all heterogeneity, can be structured at a higher level of the ladder of abstraction without losing complexity. A phenomenological perspective of analysis can help to control one’s own assumptions, to grasp and contextualize individual meanings of democracy, and to create more complex taxonomies.

To illustrate this, we will use the data and findings of two qualitative studies on democracy and participation (Frankenberger et al. 2015; Frankenberger, Gensheimer und Buhr 2019) for which we conducted 275 face-to-face qualitative interviews in the period from January to July 2014 and 114 qualitative interviews by telephone and face-to-face in the period from March to September 2017 with residents of the state of Baden-Württemberg (Table 1).

Even if the sample of people interviewed is not representative, its breadth covers most age, educational, and occupational groups and provides deep insights into individual lifeworlds. The interviews, which lasted between 20 and 110 min, were each recorded with the consent of the respondents and transcribed verbatim. The analysis of the data was carried out using the analysis software MaxQDA.

2.1 Evoking the respondents’ “world at hand”—a phenomenological perspective on meanings of democracy

Phenomenology as a philosophical and methodological approach is “rooted in the notion that all of our knowledge and understanding of the world comes from our experience” (Spencer et al. 2014, p. 88). If we want to understand and explain social phenomena from the perspective and actions of individuals, we need to refer “back to the subjective meaning which these actions have for the actors themselves” (Hitzler and Eberle 2004, p. 68). However, pure phenomenological research in political science is rare. It has rather been applied in sociology, psychology, social psychology (cf. Langdridge 2008), ethnography (cf. Eberle 2015), and archeology (cf. Hamilton et al. 2006). As we will show, making use of phenomenologist methodology offers more detailed insights in subjective meanings of democracy.

Survey research with its positivistic and objectifying understanding of science produces “second-order understandings of the world” that are already transformed and interpreted through and by theoretical considerations. Phenomenological research, on the other hand, aims “to provide a first-order understanding through concrete description” (Brinkmann 2014, p. 287). Phenomenologists are “primarily concerned with questions around the nature of our subjective experience. Attention is on the specific ways in which individuals consciously reflect on and experience their lifeworld. The person is viewed as a conscious actor who actively constructs meaning” (Langdridge 2008, p. 1128). Phenomenological research thus relies on people’s articulations of experiences and knowledge. One core task is to “get as close an understanding of the participants’ lived experiences, as is possible. This involves us in becoming aware of our own beliefs, biases and assumptions and setting them to one side in order that we can see the world through our participants’ eyes” (Langdridge 2008, p. 1129; see also Spencer 2014, p. 88). Following this argumentation, bracketing or “époché” are the most important methodological claims in phenomenology. We first have to explore our own biases and assumptions before we can uncover the assumptions and biases of others.

For interviewers, this means becoming aware of their own meaning of democracy—ideally in a group—and, when interviewing, always remember that they should not let their own ideas flow into the interview, but only ask open and critical questions, which in turn can be checked for bias using the interview transcripts and, if necessary, corrected for in further interviews. In this way, one of the initially criticized problem areas of survey research can be controlled and corrected. Through successful bracketing researchers can ensure that one does not measure agreement with one’s own ideas of democracy, but rather the original views of the interviewees. In an interview, this is reflected in an open-ended question like “What does democracy mean to you?” or “What do you understand by democracy?”, which may be followed by further questions to clarify concepts and terms.

One phenomenological attempt to discover the structures and meanings of individual experiences is the lifeworld approach developed by Alfred Schütz (Schütz 1966, 1970; Schütz and Luckmann 2003). For Schütz everyday life constitutes the horizons of experience that create specific knowledge. Schütz argues that the “world of daily life” constitutes “a biographically determined situation (…) within which man has his position, not merely his position in terms of physical space and outer time or of his status and role within the social system but also his moral and ideological position (…) this biographically determined situation includes certain possibilities of future practical or theoretical activities which shall be briefly called the ’purpose at hand” (Schütz 1970, p. 73). For Schütz, it is clear that a normal adult develops their interests and preferences as a member of a historical community (Schütz and Luckmann 2003, p. 506). Experiences in the lifeworld determine and guide action, as they provide a specific set of reality, meaning, and a stock of knowledge. It represents the reality that modifies our action, and that is modified through action (Schütz and Luckmann 2003, p. 33). Action in this context is the execution or actualization of a pre-designed experience that is rooted in the experiences made within each respective lifeworld (Hitzler 1997, p. 115).

One of the main purposes of Alfred Schütz’ phenomenological analysis is to find out how we can understand other people without having any direct access to their consciousness. It is only possible to understand the other “through the signs and indications” that this other person uses (Hitzler and Eberle 2004, p. 69). Understanding therefore is always interpretive and fragmentary, and as such only an approximation of subjective meaning. As Hitzler and Eberle (2004, p. 69) point out, Schütz’ methodological reflection is based on two postulates. First the posit of subjective interpretation, and second the posit of adequacy. The former means that social science explanation has be rooted in subjective meaning, whereas the latter requires constructions of social scientists to be consistent with the constructions of ordinary people acting in their lifeworld. So, the only guarantee that social reality is not substituted by a non-existing, fictional world constructed by a scientific observer is to use the subjective perspective as the last point of reference, even though adequacy might never be fully reached (Hitzler and Eberle 2004, p. 69).

3 Methodology and core findings 1: gathering data

When interviewees actively name, describe and define areas of their lifeworld, then they are presenting their “world at hand” (Schütz and Luckmann 2003). In doing so, they describe the stratifications of their everyday world, the stores of knowledge, subjective experiences, and social relations as central sources of their construction of the lifeworld. Methodologically, phenomenological research has to draw on methods that emphasize gathering data on lived experience from the participants’ perspective, like ethnomethodology or narrative analysis (cf. Spencer et al. 2014, p. 89). For the purpose of gathering relevant information on political lifeworlds, qualitative, semi-structured interviews are probably more adequate than pure narration. Semi-structured interviews make use of the “knowledge-producing potentials of dialogues” and at the same time avoid a driftage away from the themes the interviewer is interested in, as the “interviewer has a greater say in focusing the conversation on issues that he or she deems important in relation to the research project” (Brinkmann 2014, p. 286). Such qualitative interviewsFootnote 3 are conducted to produce knowledge: “In line with a widespread phenomenological perspective, interviewers are normally seeking descriptions of how interviewees experience the world, its episodes and events, rather than speculations about why they have certain experience. Good interview questions thus invite interviewees to give descriptions” (Brinkmann 2014, p. 287).

In our research we used semi-structured interviews to evoke episodes concerning the dimensions of interest, namely meanings of democracy and polity/politics. The interviews were structured by open questions that address the various dimensions of everyday life with a focus on democracy and politics (cf. Table 2). To get an overview of important lifeworld references beyond democracy, polity, politics, and policy, we also asked for statements on the eight dimensions of everyday experiences, which constitute the lifeworld: work world, family life, leisure behavior, social contacts, consumption wishes and goals, perspectives of life, basic political attitude, and reverie (Flaig et al. 1994).

Interviewers had instructions to let people elaborate on their perspectives, to encourage them to add details, and to ask follow-up questions in order to clarify definitions and concepts as well as to add examples in order to get thick descriptions of individual lifeworlds.

Almost all respondents were able to answer the question of their meanings of democracy with more than one keyword, such as equality, freedom, freedom of opinion, or popular sovereignty. Many respondents told longer and more elaborate stories about what they associate with democracy. The analysis also revealed that respondents made references to democracy at other points in the interviews and added further details about their individual meanings of democracy. The following interview passages, originally recorded in German, illustrate the sometimes rich and detailed responses of the respondents.

Interviewee 4 from sample 2 is a 33-year-old working man who considers himself to be middle class, conservative to right-wing, and describes himself as honest and direct. His meaning of democracy is strongly focused on individual norms, and he sees these norms as endangered:

I: And when you think of the concept of democracy—what comes to your mind spontaneously?

R4: Yes, of course the basic principles of separation of powers and the rule of law are part of it, and by democracy I also understand that extreme opinions must be endured, no matter in which direction they go. That everyone has the right to express himself freely and without fear.

I: So, you have now put the focus on freedom of expression. Are there any other qualities or values that are important to you in a democracy or what you understand by democracy?

R4: Yes, exactly what I mentioned at the beginning, the basic principles. But apart from that, yes, my focus is also on freedom of opinion. Access to public office should be open to every citizen, regardless of skin color, age or whatever. Yes, actually also very self-evident things.

I: Okay, and if you think of Germany as a democracy—what do you like? What do you dislike more?

R4: I’m not even that satisfied with the political system. In my opinion, it has deteriorated considerably in recent years. Precisely what I said, that even opinions that are perhaps not shared by the broadest section of the population, that they are simply not tolerated and are quasi, yes, systematically almost suppressed.

When asked for possibilities of participation later in the interview, he adds more details to his meaning of democracy:

R4: No, I don’t think there are a great many opportunities for the average citizen. Personally, I wouldn’t wish for much more either, because I think that in democracy it is not the citizens’ task to intervene in a very concrete way, but that we have a lot of politicians in all kinds of bodies who should take over this task. That is their job.

Interviewee 21, also from sample 2, is a 58 year-old woman. She works as a kindergarten teacher. For her, democracy is …

R21: Hew, democracy. Actually, that everyone has the right to be the way they want to be. Unless she breaks boundaries or rise above boundaries that hurt others or go too far for others.

I: So it is what exactly?

R21: That would be democracy for me, and that of course if ten people (laughs) have an opinion and ten people want something, for example, that a single person can’t go over the ten people. That would be democracy for me.

I: So democracy is part of everyday life?

R21: Yes.

I: So that everyone has the right, as you said, everyone has the right to be as they want to be, and that now a minority does not hinder a majority.

R21: Exactly.

I: And may the majority hinder the minority?

R21: You can discuss it (laughs), you can exchange ideas. Yes, I think as long as it doesn’t restrict the others, it’s okay that the minorities survive too (laughs).

In our interviews we received different statements about what democracy means to individuals. However, one aim of the study was to find out whether patterns or types of meaning of democracy could be identified in the interviews. From a phenomenological perspective, such analysis must take into account that the subjectivity of the statements made in the interviews forms the basis for any abstraction. We must always control and reflect our “second-order explanations” on the statements of ordinary people to ensure their adequacy. Classifications of meanings of democracy must therefore be strictly derived from the statements of the interviewees.

4 Methodology and core findings II: analysing and aggregating data

We used a multi-step approach based on the basic assumptions of qualitative content analysis (see Kracauer 1952; Merten 1981; Lamnek 1995) to evaluate the data. By mixing the structure and openness of qualitative content analysis, it is possible both to analyze the respondents’ meanings of democracy and, going beyond that, to find connections between the individual concepts and dimensions of life, and to develop a typology of political life worlds.

In a first step, the interviews were thematically coded according to the dimensions of the lifeworld asked for in the interviews (Hopf et al. 1995; Hopf and Hopf 1997). For this purpose, the questions were used to define categories along which the text material was roughly coded. The smallest coding unit was a single word, and the largest coding unit was a section of content that is meaningfully connected—i.e., refers to the relevant category in terms of content and language. Table 3 shows a selection of the superordinate categories coded in the first step with the respective coding rules and frequencies:

In a second analysis step, the text passages of each main category were fine-coded. The object of the detailed analysis was, on the one hand, to grasp the semantic breadth and variance within the main categories with the aim of capturing different meanings of democracy and the other concepts we asked for. For example, in the category democracy, different meanings of democracy were fine-coded. References to individual norms such as freedom of opinion or separation of powers as well as to elections and plebiscites were found as procedures. These were usually used as in vivo codes for the fine coding. With 150 codes, elections were coded most frequently, followed by direct decisions/plebiscites (81), deliberative procedures (65), and then freedom of speech (59). Table 4 gives a complete overview of the codes and their frequencies.

On the other hand, the aim of the detailed analysis was to structure and reduce the material. In the process, the coded text passages were compiled, arranged in terms of content and systematized (Kuckartz 2014, p. 84). On this basis, we condensed these detailed codes and merged them into six more abstract categories of meanings of democracy (Table 5). These abstract categories were then used were formed, in order to differentiate various dimensions of the main categories and to enable the formation of types.

In our initial study (Frankenberger et al. 2015) we were able to identify six different categories of meanings of democracy. Only 26 out of 275 persons (9.45%) were unable (or unwilling) to actively produce an individual meaning of democracy. 36 interviewees (13.09%) just mentioned single issues like power, plebiscites or sovereignty without any further elaboration during the interviews. They formulated a rudimentary meaning of democracy. Eighty out of 275 interviewees (29%) referred to one or several norms as their core meaning of democracy. Freedom of expression, other civil liberties, basic political rights, and equality were mentioned and explained by the interviewees. This category comes closest to what Canache (2012) or Dalton et al. (2007) identified as the liberal understanding of democracy. The following three meanings are different from those found by Canache (2012) or Dalton et al. (2007). The largest portion of interviewees (96, or 34.9%) expressed representative meanings of democracy. They produced elaborated notions of general elections, representatives and parliaments that make decisions for the people. It might also be interpreted as an elitist meaning of democracy. Another 43 (15.6%) defined democracy in a deliberative way. For them democracy means a political system where people can express their interests within the policy process and that these interests find their way into the political decisions usually made by representatives. 51 of the interviewees (18.5%) highlighted direct democracy and plebiscitarian elements. Meanings of democracy as “power by the people” and decision-making by the people with explicit references to plebiscitarian procedures were typical for these interviewees. In the follow up study (Frankenberger et al. 2019), we again asked for individual meanings of democracy and these categories remained quite stable even though they were distributed differently (no meanings of democracy: 18, or 15.7%; rudimentary: 50, or 43.8%; norm-oriented: 77, or 67.5%; representative: 44, or 38.6%; deliberative 15, or 13.2%; direct: 24, or 21%).Footnote 4 We did not find new substantial meanings of democracy meaning that for at least the last five years in the state of Baden-Wuerttemberg, existing forms of meanings of democracy were quite stable.

5 Methodology and core findings III: building typologies by linking concepts

To work phenomenologically does not mean that one has to or should work without typologies or causal argumentations. However, one should be particularly careful when constructing typologies. Thomas Eberle (2010, p. 125 f), for example, argues that explanations and typologies must satisfy the criteria relevance, logical consistency, subjective interpretation, adequacy, and rationality. He argues that adequacy of meaning can only be achieved if the explanatory understanding is evident and causally adequate. Alfred Schütz rejected the idea of causal adequacy (Schütz 1967, p. 232) and saw in it only a special case of meaning adequacy. Eberle argues that Schütz therewith “dropped the requirement of empirical verification from the postulate of adequacy” (Eberle 2010, p. 128). In the sense of an empirical analysis of the meanings of democracy, this is a shortcoming since democracy researchers are particularly interested in empirical verification of theoretical explanations. Eberle (2010, p. 131) thus proposes a more restrictive interpretation of adequacy that includes empirical appropriateness in order to avoid over-simplification: “The postulate of adequacy means that the constructs of the social scientist describe and explain a concrete course of action empirical appropriately in the actor’s perspective”. He highlights the empirical appropriateness of theoretical concepts that should be related to concrete experiences of actors: “This does not mean that scientific ideal types must relate to the actors’ common-sense typifications, but (…) that scientific constructions must relate to how actors actually make sense in their everyday life. Schütz’ analysis of meaning constitution in the social world provides the link between the constructions of the first and second order” (Eberle 2010, p. 133).

The construction of types of individual lifeworlds based on individual meanings of democracy is an example of such an approach that meets the criterion of adequacy. The qualitative interviews showed that the individually expressed meanings of democracy are linked to other concepts such as politics and participation. With regard to the concept of politics, the interviews repeatedly revealed cross-referenced, delimited, and connected definitions.

We therefore examined the meanings of the term “Politik” analogous to the term democracy.Footnote 5 Overall, we found six different meanings of “Politik”, that crosscut the categories of meanings of democracy, as they were outlined above (Dalton et al. 2007; Canache 2012; Canache et al. 2012). In both studies, we found a small portion of interviewees who were unable or unwilling to elaborate on “Politik” (9.5 and 15.8%). They either did not reflect the topic or used empty signifiers (like democracy) to express their concepts and these signifiers stayed empty even if interviewers asked for explanations. 41.4 and 32.1% respectively expressed governmental meanings that highlighted variations of “politics is what the governments do”. Another portion of respondents in both studies (25.4% vs. 57.9%) referred to rules and procedures that underly the organization of the community or polity. They highlighted the regulation of common interests and the formation of the public sphere. The fourth meaning of “Politik” comprised all kinds of political institutions on local, regional and national (and even supra-national) levels as a point of reference (31.3% vs. 21%). 24 and 8.7% showed emancipatory notions of “Politik” such as “I am political when I am trying to change society”. Last but not least, a small portion of interviewees see all of life as political (14.1 and 13.1%) and consequently interpret most of their own actions as political.

These results taken together with our results on democracy, provide evidence that disentangling and then linking these two dimensions adds value to studies of democracy and democratization, as they allow researchers to discriminate between meanings of democracy versus meanings of “Politik”. It offers explanations for why so many people a) want political democracy—often because of very specific and subjective expectations concerning what democracy should be and can deliver—and b) become dissatisfied with democracy when their expectations are not met, even though they rather might be discontent with the actual regime than with the polity as such. Especially in our interviews with dissatisfied people, we found many such cases. Many of these interviewees had a governmental orientation and compounded dissatisfaction with the performance of the current German Federal government and its actual policies and policy outcomes (especially refugee and migration policies) with their subjective meanings of democracy. They related their dissatisfaction directly to a crisis of representative democracy and advocated for more direct democracy. If we only asked for meanings of democracy or satisfaction with democracy, we might have misleadingly captured their dissatisfaction with policies and governments as dissatisfaction with democracy as such, given that we then would not have had the opportunity to ask further questions. These and other findings clearly highlight the assets of qualitative research on meanings of democracy.

In our studies (Frankenberger et al. 2015; Buhr et al. 2019) we used meanings of democracy and meanings of “Politik” as well as individual patterns of participation to build a second order typology of political lifeworlds. The common appearance of political and democratic meanings in the interviews serves as a basis, as Table 6 illustrates.

Political lifeworlds can be briefly grouped into three clusters: distant, delegative and participatory lifeworlds. Politically distant lifeworlds show rudimentary knowledge of democracy and generally comes with distance to politics and almost no participatory behavior. “People from politically distant lifeworlds scarcely participate and if they do so, only punctually and rather in a social setting. (…) They contain the apolitical und distant lifeworlds” (Frankenberger and Buhr 2017, p. 81). Delegative lifeworlds are characterized by strong orientations on norms, rules and institutions of political life. Representative and norm-oriented meanings of democracy are strongly linked with government and rule based fixed terms of politics. They are the backbone of representative democracy and include electorate as well as elected officials and representatives. People in these lifeworlds often are politically and/or socially active, even though the level of participation usually is low or medium and focused on individually and directly relevant aspects. These delegative lifeworlds can be differentiated into Carers, Electorate, and Doers. Participatory lifeworlds are defined by a participatory meaning of democracy and emancipatory approaches to politics: “The belief that active influence and shaping is possible is a core element of this group. Following that, people in these lifeworlds are politically and socially especially active and advocate for themes and persons. (…) These are the co-creators and co-deciders.” (Frankenberger and Buhr 2017, p. 81)Footnote 6. Such a multi-dimensional construct not only takes complexity of everyday life into account, but also the notion of lifeworld as a bounded whole that hardly can be reduced to a single indicator or item in a survey. Or as Brinkmann (2014, p. 288) puts it: “lifeworld phenomena are rarely transparent and “monovocal” but are rather “polyvocal” and sometimes even contradictory, permitting multiple readings and interpretations”. Carefully constructed, such a typology of political lifeworld can be used as independent variable for explaining political opinions as well as action and still represent this polyvocality. Our political lifeworld is the mindset that guides our perceptions of the world and forms the ground on which we build our future beliefs and actions. This does not mean that individual political lifeworlds are static (e.g. think of critical junctures or key moments in the lifecycle that can vastly influence and radically change our individual constructions of politics [cf. Frankenberger et al. 2015]), but at the moment of concern it is the major precondition and driving force that makes us act or not.

6 Conclusion

In this article we argued that survey research produces incomplete results in measuring meanings of democracy due to methodological limits associated with standardized research. Even open questions included in survey research cannot fully solve this problem. Drawing from a phenomenological perspective of methodology and experience from 389 qualitative interviews conducted using this approach, we argued that evoking the “world at hand” of interviewees might be possible through open questions in surveys, but they still cannot reveal much more than a curtate meaning of democracy.

Meanings of democracy are far more complex than results of survey research imply as they are intertwined with other individual concepts and subjective experiences. In terms of phenomenological adequacy, they are important first order constructions that can be used for building second order typologies and explanations for political action. Survey-based quantitative research has clear limits in terms of gathering such first order constructions, even if one wants to integrate them. As the examples discussed above have shown, introducing one or two open questions is one possibility to broaden the perspective and leverage for causal inference, as there are at least some subjective notions of democracy included. Qualitative analyses of meanings of democracy meet the standards of phenomenological methodology, especially adequacy, but in turn are difficult to implement in survey research.

Furthermore, subjective meanings of democracy are important parts of the respondents’ “world at hand” or political lifeworld that guides political cognition and action. Methodologically speaking, political lifeworlds are “bounded wholes”, that might be separated into different spheres for analytical purposes. In terms of adequacy, they must be carefully interpreted, rebuilt and constructed by using the first order constructions of individuals. Therefore, we suggest using open, qualitative methods inspired by phenomenological methodology to get as close as possible to subjective first order constructions of meanings of democracy. These in turn can be used to formulate phenomenologically adequate second order constructions of meanings of democracy.

Such a multi-dimensional analysis then offers further and more detailed opportunities to develop a typology of political lifeworlds that can be used as an independent variable for explaining political opinions as well as political behavior. The findings of this research can also be used for more standardized research. If second order constructions of meanings of democracy are adequate phenomenologically, we can use in-vivo codes generated from qualitative data that are considered typical for a certain meaning of democracy by both scientists and interviewees as items in standardized surveys and frequently triangulate them by using corresponding open questions. Using the answers from these standardized items and open questions may yield better data than simply asking an open question. Similar to the study by Andersen et al. (2018), these in-vivo codes could be used in surveys implementing q‑methodology. They could also be used directly for cluster analysis like the one implemented by Schedler and Sarsfield (2007).

Finally, if we want to measure meanings of democracy in a substantive way that also accounts for changes and variance in meanings of democracy over time and space and between respondents, we would be well advised to use qualitative measurements at least in regular turns in order to detect current subjective meanings and potential changes in first-order constructions of democracy.

Change history

27 September 2021

An Erratum to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-021-00493-6

Notes

The index includes the following four items on political preferences: A‑Having a democratic political system is a good way of governing this country; B‑democracy may have problems but it’s better than any other form of government; C‑Having experts, not the government, make decisions according to what they think is best for the country; and D‑Having a strong leader who does not have to bother. The values of the answer are computed as (A + B) − (C + D) to get the index-value. This points at a main shortcoming of such measurements: they do not really take into account any differentiation of what people associate with democracy, even though the WVS offers nine attributes that people shall evaluate in terms of whether these attributes are essential characteristics of democracy or not. For wave 6 of the WVS this includes variables 131 to 139 (redistribution, secularization, free elections, unemployment compensation, Interventionism by armed forces, protection from state oppression, income equality, obedience, and equal rights; cf. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp).

Q‑Methodology is used to analyze human subjectivity. It is implementing Q‑type factor analysis for finding correlations between subjects across a sample of variables. It reduces individual viewpoints down to some factors that represent shared ways of thinking. Data for analysis is generated by so called “Q-sorts” where individuals have to rank predefined statements according to predefined instructions. (cf. Andersen et al. 2018; Stephenson 1982).

Qualitative Interviews are defined as “an Interview with the purpose of obtaining descriptions of the lifeworld of the interviewee in order to interpret the meaning of the described phenomena” (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009, p. 3).

Some people expressed more than one meaning. Therefore, the absolute numbers of expressions exceed the numbers of participants. Different distributions in the two studies are caused by different target groups. In the first study we aimed at compiling a more representative sample than in the second study, where we explicitly recruited people that are discontent with democracy (as they understand or experience it).

Research was conducted in German and we therefore here use the German word “Politik”.

References

Cited Literature

Almond, Gabriel, and Sidney Verba. 1963. The civic culture. Political attitudes and democracy in five nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Andersen, Rune Holmgaard, Jennie L. Schulze, and Külliki Seppe. 2018. Pinning down democracy: a Q‑method study of lived democracy. Polity 1(50):4–42.

Ariely, Gal. 2015. Democracy-assessment in cross-national surveys: a critical examination of how people evaluate their regime. Social Indicators Research 121(3):621–635.

Bollen, Kenneth A. 1990. Political democracy: conceptual and measurement traps. Studies in Comparative International Development 25(1):7–24.

Bratton, Michael. 2010. Anchoring the “D-Word” in comparative survey research. Journal of Democracy 21(4):106–113.

Bratton, Michael, Robert Mattes, and Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi. 2005. Public opinion, democracy, and market reform in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brinkmann, Svend. 2014. Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing. In The Oxford handbook of qualitative research, ed. Patricia Leavy, 277–299. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Browers, Michaelle L. 2006. Democracy and civil society in Arab political thought: transcultural possibilities. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Buhr, Daniel, Rolf Frankenberger, and Tim Gensheimer. 2019. Mehr Demokratie ertragen? In Demokratie-Monitoring Baden-Württemberg 2016/17, ed. Baden-Württemberg Stiftung, 85–102. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Canache, Damarys. 2012a. Citizens’ conceptualizations of democracy: structural complexity, substantive content, and political significance. Comparative Political Studies 45(9):1132–1158.

Canache, Damarys. 2012b. The meanings of democracy in Venezuela: Citizen perceptions and structural change. Latin American Politics and Society 54(3):95–122.

Canache, Damarys, Jeffery J. Mondak, and Mitchell A. Seligson. 2001. Meaning and measurement in cross-national research on satisfaction with democracy. Public Opinion Quarterly 65(4):506–528.

Canovan, Margaret. 1999. Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy. Political studies 47(1):2–16.

Carnaghan, Ellen. 2011. The difficulty of measuring support for democracy in a changing society: evidence from Russia. Democratization 18(3):682–706.

Christophersen, Jens. 1966. The meaning of democracy as used in European ideologies from the French to the Russian revolution. Oslo: Oslo University Press.

Collier, David, and Steven Levitsky. 1997. Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Politics 49(3):430–451.

Collier, David, Fernando Daniel Hidalgo, and Andra Olivia Maciuceanu. 2006. Essentially contested concepts: debates and applications. Journal of Political Ideologies 11(3):211–246.

Coppedge, Michael. 2012. Democratization and research methods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, Steven Fish, Allen Hicken, Matthew Kroenig, I. Lindberg Staffan, Kelly McMann, Pamela Paxton, Holli A. Semetko, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, and Jan Teorell. 2011. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: a new approach. Perspectives on Politics 9(2):247–267.

Dalton, Russell J., and Hans-Dieter Klingemann. 2007. The Oxford handbook of political behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dalton, Russell J., and Doh Chull Shin. 2006. Citizens, Democracy and Markets around the Pacific Rim. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Dalton, Russell J., Doh Chull Shin, and Willy Jou. 2007. Understanding democracy: data from unlikely places. Journal of Democracy 18(4):142–156.

De Moor, Joost. 2017. Lifestyle politics and the concept of political participation. Acta Politica 52(2):179–197.

Diamond, Larry, and Marc F. Plattner. 2008. How people view democracy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dryzek, John S., and Jeffrey Berejikian. 1993. Reconstructive democratic theory. American Political Science Review 87(1):48–60.

Dryzek, John S., and Leslie Templeman Holmes. 2002. Post-communist democratization: political discourses across thirteen countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Easton, David. 1975. A re-assessment of the concept of political support. British Journal of Political Science 5(4): 435–457.

Easton, David. 1965. A systems analysis of political life. New York: Wiley

Eberle, Thomas S. 2010. The phenomenological life-world analysis and the methodology of the social sciences. Human Studies 33(2–3):123–139.

Eberle, Thomas S. 2015. Exploring another’s subjective life-world: a phenomenological approach. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 44(5):563–579.

Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2016. How Europeans view and evaluate democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flaig, Bodo B., Thomas Meyer, and Jörg Ueltzhöffer. 1994. Alltagsästhetik und Politische Kultur. Zur ästhetischen Dimension politischer Bildung und politischer Kommunikation. Bonn: Dietz Verlag.

Frankenberger, Rolf, and Daniel Buhr. 2017. Political Lifeworlds in Baden-Württemberg. In Local politics in a comparative perspective, ed. Rolf Frankenberger, Elena Chernenkova, 77–88. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Frankenberger, Rolf, Daniel Buhr, and Josef Schmid. 2015. Politische Lebenswelten. In Demokratie-Monitoring Baden-Württemberg 2013/2014, ed. Baden-Württemberg Stiftung, 151–221. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Frankenberger, Rolf, Tim Gensheimer, and Daniel Buhr. 2019. Zwischen Mitmachen und Dagegen sein. Politische Lebenswelten in Baden-Württemberg. In Demokratie-Monitoring Baden-Württemberg 2016/17, ed. Baden-Württemberg Stiftung, 149–172. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Fuchs, Dieter. 1999. The democratic culture of united Germany. In Critical citizens, ed. Pippa Norris, 123–145. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuchs, Dieter. 2007. The political culture paradigm. In The Oxford handbook of political behavior, ed. Russell J. Dalton, Hans-Peter Klingemann, 161–184. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gagnon, Jean-Paul. 2018. 2,234 Descriptions of democracy. An update to democracy’s ontological pluralism. Democratic Theory 5(1):92–113.

Gagnon, Jean-Paul, and Danica Fleuss. 2020. The case for extending measures of democracy in the world “Beneath”, “Above”, and “Outside” the national level. Political Geography 83:102276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102276.

Gallie, Walter Bryce. 1956. Essentially contested concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian society 1955–1956:167–198.

Hamilton, Sue, Ruth Whitehouse, Keri Brown, Pamela Combes, Edward Herring, Mike Seager Thomas, (2006) Phenomenology in practice: towards a methodology for a ‘subjective’ approach. European Journal of Archaeology 9 (1):31–71

Hitzler, Ronald. 1997. Politisches Wissen und politisches Handeln: einige phänomenologische Bemerkungen zur Begriffsklärung. In Soziologie und politische Bildung, ed. Siegfried Lamnek, 115–132. Leverkusen: Leske + Budrich.

Hitzler, Ronald, and Thomas S. Eberle. 2004. Phenomenological life-world analysis. In A companion to qualitative research, ed. Uwe Flick, Ernst von Kardorff, and Ines Steinke, 67–71. London: SAGE.

Hopf, Christel, and Wulf Hopf. 1997. Familie, Persönlichkeit, Politik. Eine Einführung in die politische Sozialisation. Weinheim: Beltz.

Hopf, Christel, Peter Rieker, Martina Sanden-Marcus, and Christiane Schmidt. 1995. Familien und Rechtsextremismus. Familiale Sozialisation und rechtsextreme Orientierungen junger Männer. Weinheim: Juventa.

Inglehart, Ronald. 2003. How solid is mass support for democracy—and how can we measure it? PS: Political Science & Politics 36(1):51–57.

Jamal, Amaney, and Mark Tessler. 2008. How people view democracy: attitudes in the Arab world. Journal of Democracy 19(1):36–47.

Karlström, Mikael. 1996. Imagining democracy: political culture and democratisation in Buganda. Africa 66(4):485–505.

Kracauer, Siegfried. 1952. The challenge of qualitative content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly 16(4):631–642.

Kuckartz, Udo. 2014. Qualitative text analysis: A guide to methods, practice and using software. London: Sage

Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2009. Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Thousands Oaks: SAGE.

Lamnek, Siegfried. 1995. Methoden und Techniken. Qualitative Sozialforschung, Vol. 2. Weinheim: Beltz.

Langdridge, Darren. 2008. Phenomenology and critical social psychology: directions and debates in theory and research. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2(3):1126–1142.

Lu, Jie. 2013. Democratic conceptions in East Asian societies: a contextualized analysis. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 9(1):117–145.

McKeon, Richard. 1951. Democracy in a world of tensions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Merten, Klaus. 1981. Inhaltsanalyse als Instrument der Sozialforschung. Analyse & Kritik 3(1):48–63.

Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2012. Populism in europe and the americas: threat or corrective for democracy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. Exclusionary vs. inclusionary populism: comparing contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition 48(2):147–174.

Munck, Gerardo L., and Jay Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy: evaluating alternative indices. Comparative Political Studies 35(1):5–34.

Naess, Arne. 1956. Democracy, ideology and objectivity. Oslo: Oslo University Press.

Schaffer, Frederic Charles. 2000. Democracy in Translation: understanding politics in an unfamiliar culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Schaffer, Frederic Charles. 2014. Thin descriptions: the limits of survey research on the meaning of democracy. Polity 46(3):303–330.

Schedler, Andreas, and Rodolfo Sarsfield. 2007. Democrats with adjectives: linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. European Journal of Political Research 46(5):637–659.

Schütz, Alfred. 1966. Some structures of the lifeworld. In Collected papers vol. III: studies in phenomenological philosophy, ed. Ilse Schütz, 116–132. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schütz, Alfred. 1967. Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press

Schütz, Alfred. 1970. On Phenomenology and social relations. Selected writings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schütz, Alfred, and Thomas Luckmann. 2003. Strukturen der Lebenswelt. Konstanz: UKV.

Shi, Tianjian. 2009. Is there an asian value? Popular understanding of democracy in Asia. In China’s reforms at 30: challenges and prospects, ed. L. Yang Dali, Litao Zhao, 167–194.

Shin, Doh Chull. 2007. Democratization: Perspectives from global citizenries. In The Oxford handbook of political behavior, ed. Russell J. Dalton, Hans-Peter Klingemann, 259–282. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shin, Doh Chull, and Hannah June Kim. 2018. How global citizenries think about democracy: an evaluation and synthesis of recent public opinion research. Japanese Journal of Political Science 19(2):222–249.

Spencer, Renée, Julia M. Pryce, and Jill Walsh. 2014. Philosophical approaches to qualitative research. In The Oxford handbook of qualitative research, ed. Patricia Leavy, 81–98. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stephenson, William. 1982. Q‑methodology, interbehavioral psychology, and quantum theory. Psychological Record 32:235–248.

Taggart, Paul. 2004. Populism and representative politics in contemporary Europe. Journal of Political Ideologies 9(3):269–288.

Verba, Sidney. 2000. Representative democracy and democratic citizens: philosophical and empirical understandings. Tanner Lectures on Human Values 21:229–288.

Weyland, Kurt. 1999. Neoliberal populism in Latin America and eastern Europe. Comparative Politics 31(4):379–401.

Yannis Theocharis, Jan W. van Deth, (2018) The continuous expansion of citizen participation: a new taxonomy. European Political Science Review 10 (1):139–163

Further Reading

Hopf, Christel, and Christiane Schmidt. 1993. Zum Verhältnis von innerfamiliären sozialen Erfahrungen, Persönlichkeitsentwicklung und politischen Orientierungen. Hildesheim: Institut für Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hildesheim.

Osterberg-Kaufmann, Norma. 2016. How People View Democracy: Messprobleme und mögliche Alternativen. In “Demokratie” Jenseits des Westens Politische Vierteljahresschrift, Sonderheft 51., ed. Sophia Schubert, Alexander Weiß, 343–365.

Pye, Lucian W. 1968. Political culture. International encyclopedia of the social sciences 12:218.

Reisinger, William M. 1995. The renaissance of a rubric: political culture as concept and theory. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 7(4):328–352.

Sandel, Michael J. 1998. Democracy’s discontent: America in search of a public philosophy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schütz, Alfred, and Talcott Parsons. 1978. The theory of social action: the correspondence of Alfred Schutz and Talcott Parsons. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Schütz, Alfred. 1962. The problem of social reality. Collected papers, Vol. I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schütz, Alfred. 1964. Studies in social theory. The problem of rationality in the social world. In Collected papers, Vol. II, 64–88. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schütz, Alfred. 1972. Gesammelte Aufsätze. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff.

Schütz, Alfred. 1981. Theorie der Lebensformen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Shin, Doh Chull, and Youngho Cho. 2010. How East Asians understand democracy: From a comparative perspective. Asien 116:21–40.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahnemann. 1973. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology 5(2):207–232.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Norma Osterberg-Kaufmann, Toralf Stark and Christoph Mohamad-Klotzbach for their support and for initiating the workshop “Measuring Understanding of Democracy” in Berlin in August 2018. Credits go to all participants of the workshop for comments and stimulative discussions. We thank two anonymous reviewers for their excellent support and advice to improve the first version of the article. Field research would not have been possible without Benjamin Kummer, Stewart Gold and Tim Gensheimer. Matthew McCormick proofread the article and played a major role in improving the article linguistically. We are responsible for the remaining errors.

Funding

The data referred to in this article were generated in two projects on political lifeworlds within the framework of the “Demokratie-Monitoring Baden-Württemberg” funded by the Baden-Württemberg Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

R. Frankenberger and D. Buhr declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Frankenberger, R., Buhr, D. “For me democracy is …” meanings of democracy from a phenomenological perspective. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 14, 375–399 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-020-00465-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-020-00465-2