Abstract

Human and animal studies suggest an interaction between the Pro12Ala polymorphism of PPARG and dietary fat. In this randomized crossover clinical trial, we investigated whether subjects with the Pro12Pro and Ala12Ala genotypes of PPARG respond differently to a diet supplemented with high saturated (SAFA) or polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA).We recruited non-diabetic men from a population-based METSIM study (including 10,197 men) to obtain men with the Ala12Ala and the Pro12Pro genotypes matched for age and body mass index. Seventeen men with the Pro12Pro genotype and 14 with the Ala12Ala genotype were randomized to both a PUFA diet and a SAFA diet for 8 weeks in a crossover setting. Serum lipids and adipose tissue mRNA expression were measured during the diet intervention. At baseline, subjects with the Ala12Ala genotype had higher levels of HDL cholesterol and lower levels of LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein B compared to those subjects with the Pro12Pro genotype (P < 0.05, FDR < 0.1). The Ala12Ala genotype also associated with higher mRNA expression of PPARG2, LPIN1, and SREBP-1c compared to participants with the Pro12Pro genotype (FDR < 0.001). On the other hand, PUFA diet resulted in lower levels of fasting glucose, total cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein B (P < 0.05, FDR < 0.1) but did not affect PPARG2 mRNA expression in adipose tissue. We conclude that individuals with the Pro12Pro genotype, with higher triglyceride levels at baseline, are more likely to benefit from the PUFA diet. However, the beneficial effects of dietary PUFA and the Ala12Ala genotype of PPARG on serum lipids are mediated through divergent mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diet and physical activity are the major lifestyle determinants of the risk of type 2 diabetes, as demonstrated in diabetes prevention studies, e.g., in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention study (Knowler et al. 2002; Tuomilehto et al. 2001). Recent genome-wide association analyses have identified >70 gene variants that contribute to type 2 diabetes (Huyghe et al. 2012; Morris et al. 2012) and >30 genes that contribute to obesity (Sandholt et al. 2012). However, none of these variants explain >5 % of the risk of these conditions, and altogether, they explain <10 % of the total disease risk (Manolio et al. 2009). Interactions between gene variants and the environment, i.e., our inherited responses to environmental changes, are likely to be crucial in the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes (Cornelis and Hu 2012). Despite a relatively small sample size, interactions between several genes, including PPARG, and lifestyle intervention have been demonstrated in randomized lifestyle intervention trials (Lindi et al. 2002; Uusitupa 2005).

We were the first to identify the Pro12Ala polymorphism of PPARG as a risk factor for type 2 diabetes. This polymorphism is expressed only in the adipose tissue-specific isoform PPARG2 of PPARG, and the Ala12 allele associates with lower transcriptional activity (Deeb et al. 1998). Low prevalence of type 2 diabetes (Altshuler et al. 2000) and dyslipidemias (Huang et al. 2011) has been associated with the Ala12 allele of PPARG. However, other studies suggest that association between the genotype and BMI may depend on obesity (Ek et al. 1999), age (Pihlajamaki et al. 2004), dietary uptake of monounsaturated fatty acids (Garaulet et al. 2011), and dietary ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acid (P/S ratio) (Luan et al. 2001). Interestingly, dietary P/S ratio has also been shown to have an interaction with PPARG genotype on the effect on serum lipids in cross-sectional studies (Alsaleh et al. 2011; Bouchard-Mercier et al. 2011), and also in an intervention trial in which saturated fatty acid was replaced by monounsaturated fatty acid (AlSaleh et al. 2012). Accordingly, animal studies suggest a complex interaction between PPARG2 and dietary fat. Mice lacking the PPARG2 isoform are more insulin-resistant compared to wild-type mice on normal chow diet but not on high-fat diet (Medina-Gomez et al. 2005). Furthermore, in Pro12Ala knock-in mice, the beneficial effects of the Ala12 allele on adiposity, plasma lipids, and insulin sensitivity are lost with a high-fat diet (Heikkinen et al. 2009).

In this study, we hypothesized that subjects with Pro12Pro and Ala12Ala genotypes respond differently to a diet supplemented with high saturated (SAFA) or polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA). This hypothesis was based on the knowledge that polyunsaturated fatty acids are ligands for PPARG (Kliewer et al. 1997; Xu et al. 1999). As opposed to previous studies investigating the putative modifying effect of the PPARG genotype in randomized dietary interventions independent of the genotype, we randomized 17 men with the Pro12Pro genotype and 14 matched controls with the Ala12Ala genotype, from a population-based METSIM study (Stancakova et al. 2012), to receive PUFA and SAFA diets for 8 weeks in a crossover setting. The specific objective of the study was to investigate whether SAFA and PUFA supplementation interferes with genetic regulation of lipid metabolism by Pro12Ala genotype.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We recruited lean and overweight subjects (BMI > 20 kg/m2 < 29 kg/m2) with the Pro12Pro and Ala12Ala genotypes of PPARG from the METSIM study (METabolic Syndrome in Men), including 10,197 men originally identified from the population register of the Kuopio town (Stancakova et al. 2012). Obese individuals were excluded to avoid the confounding effect of PPARG polymorphism on obesity and thus the secondary effects of obesity on serum lipids. One hundred and forty-seven non-diabetic subjects with the Ala12Ala genotype and an equal number of age- and BMI-matched subjects with the Pro12Pro genotype were selected from the METSIM study. A total of 31 subjects (17 with the Pro12Pro genotype and 14 with the Ala12Ala genotype) were willing to participate and were recruited. These participants did not differ from non-participants with respect to anthropometric and laboratory measurements (age 59.2 ± 6.0 vs. 59.0 ± 6.0 years, BMI 26.5 ± 2.9 vs. 27.2 ± 3.1 kg/m2, fasting glucose 6.0 ± 0.6 vs. 5.8 ± 0.7 mmol/l, and fasting insulin 49.1 ± 22.9 vs. 53.2 ± 25.6 pmol/l in participants and non-participants, respectively). There were no dropouts during the study.

Dietary interventions

Both the SAFA diet and the PUFA diet were isocaloric and contained 30 % of energy as fat, 18 % as protein, and 52 % as carbohydrates. The SAFA diet had a polyunsaturated/saturated (P/S) ratio of 0.3 and the PUFA diet 1.0. This was pursued in the SAFA diet by the consumption of medium-fat liquid dairy products, i.e., 1.5 % milk and sour milk, 2–2.5 % yoghurt, and fatty cheese (fat 24–30 %) and by using a butter and vegetable oil mixture as a spread and in cooking. Vegetable oil-based salad dressings were not allowed. Meals made of low-fat fish, e.g., perch and pike, were allowed once per week. In the PUFA diet, the subjects were instructed to use fat-free liquid dairy products (fat less than 1 %) and low-fat cheese (fat max. 17 %). Soft vegetable oil-based margarine was used as a spread and vegetable oil (low erucic acid rapeseed oil) and liquid margarine in cooking. Vegetable oil-based salad dressings were used in salads. Butter and butter-based products were not allowed during this period. Three fish meals per week (150 g of fish) with fatty fish (e.g., rainbow trout, salmon) were to be consumed. Low-fat fish was not recommended. In order to ensure compliance, the participants were given spreads, vegetable oils, liquid margarine, and cheeses free of charge during both periods. The extra costs for fish consumption during the PUFA period were reimbursed.

The two 8-week diet periods were started after a habitual diet and separated by a 2-week washout period with a habitual diet. To monitor the dietary intake, the subjects kept 4-day food records during four predefined consecutive days (Sunday–Wednesday or Wednesday–Saturday) in week 0 and twice during the diet periods (third and seventh week). The food records were checked at return by a clinical nutritionist. The physical activity was instructed to remain unchanged during the study.

The diets were planned, and the nutrient intake during the diet periods was calculated by Diet32 dietary analysis software (AivoFinland Ltd, Turku, Finland).

Clinical measurements and laboratory measurements

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared. Body composition was determined by bioelectrical impedance (RJL Systems) in subjects in the supine position after a 12-h fast. A 2-h OGTT (75 g of glucose) was performed, and samples for plasma glucose and insulin were drawn at 0, 30, and 120 min. Plasma glucose was measured by enzymatic hexokinase photometric assay (Konelab Systems Reagents, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Vantaa, Finland). Serum insulin was determined by immunoassay (ADVIA Centaur Insulin IRI, no 02230141, Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY). The InsAUC30/GluAUC30 ratio and Matsuda Insulin Sensitivity Index (ISI) (Matsuda and DeFronzo 1999) were used as surrogate markers of insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity, as previously reported (Stancakova et al. 2009).

Serum fatty acid composition

Serum lipids were extracted with chloroform–methanol (2:1), and the lipid classes were separated by solid-phase extraction with an aminopropyl column as a marker of dietary compliance (Agren et al. 1992; Vessby et al. 1980; Vidgren et al. 1997). Fatty acids were analyzed with Agilent GC 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, Wilmington, DE) equipped with a 25-m FFAP column (I = 25 m, ID = 0.2 mm, film thickness 0.33 µm; Agilent Technologies Inc.).

Adipose tissue biopsies

After an overnight fast and 30-min resting, adipose tissue samples were taken as needle biopsies from subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue at baseline, after the first dietary period (8 weeks), and at the end of the study (18 weeks) under local anesthesia (lidocaine 10 mg/ml without adrenaline). Samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Genotyping

PPARG2 polymorphism (rs1801282) was determined with the TaqMan Allelic Discrimination Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The TaqMan genotyping call rate was 100 %, with an error rate of 0 % in 4.5 % of DNA samples genotyped in duplicate.

mRNA expression

Total RNA was extracted using Tri-Reagent [Applied Biosystems (ABI) Foster City, CA, USA] and reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (ABI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out in the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System. PPARG2, ADIPOR1, and ADIPOR2 expressions were determined by the TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems) (Hs01115510_m1, Hs00360422_m1, and Hs00226105_m1, respectively) according to the protocol. PPARG2, ADIPOR1, and ADIPOR2 expressions were normalized to RPLP0 expression (Hs99999902_m1). Expression of LPIN1, FASN, SREBP-1c was determined using SYBR Green (KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit, Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA), and gene expression was normalized to RPLP0. Primer information is presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Variables with non-normal distribution were logarithmically transformed before statistical analysis. Differences between the genotype groups at baseline and after the dietary periods were examined with general linear model using the SPSS version 19 programs (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

To adjust for possible confounding factors, mixed-model analyses were performed using linear mixed effect models (nlme package version 3.1-105) (Pinheiro et al. 2015). Models were fit using a restricted maximum likelihood method ignoring missing observations. For investigating the association of a particular genotype with selected phenotypes, we included type of diet, phase of the intervention period (start or end of the period), and the week of the study (0, 8, 10, or 18) as fixed effects. For investigating the association of diet with selected phenotypes, we examined diet–phase interaction, which includes type of diet, phase of the intervention period, and the week of the study as fixed effects. In all models, subject identifier was used as a random effect. We used Benjamini–Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) to adjust for multiple testing (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). All analyses were performed using R version 2.15.2.

Results

Thirty-one non-diabetic men (17 with the Pro12Pro genotype and 14 with the Ala12Ala genotype) were randomized to receive either the PUFA or SAFA diets for 8 weeks, separated by a 2-week washout period. No significant difference in clinical parameters indicating a carryover effect after the first diet was observed. Therefore, we combined the data for SAFA and PUFA diets from the first and second periods according to the original study design. The calculated intake of energy nutrients, dietary fiber, cholesterol, and sucrose from food records during the SAFA and PUFA diets is presented in Supplementary Table 2. Estimated P/S ratio was 0.25 during the SAFA diet and 0.63 during the PUFA diet. The intake of dietary cholesterol was higher in the SAFA diet due to the use of higher fat dairy products as compared with the PUFA diet, as instructed. The intake of dietary fiber and sucrose did not differ between the diets.

The results of serum fatty acid composition analysis indicated a good compliance of the study subjects with the diets (Supplementary Table 3). Levels of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) increased, as expected in agreement with previous studies (Karvonen et al. 2002; Vessby et al. 1980; Vidgren et al. 1997), both in cholesterol esters (by 32 and 108 %, respectively, P < 1 × 10−4) and in phospholipids (by 32 and 101 %, P < 0.001) during the PUFA diet. In contrast, levels of DHA and EPA decreased in cholesterol esters (by 14 and 16 %, P < 0.001) and in phospholipids (by 12 and 15 %, P < 0.001) during the SAFA diet. In addition, levels of α-linolenic acid (ALA) increased by 11 % in cholesterol esters during the PUFA diet (P = 2 × 10−5). Overall, FDRs for a dietary effect on DHA and EPA were <10−10, verifying that participants followed the instructed diets.

Effect of the Ala12Ala genotype on serum lipids and PPARG2 mRNA expression

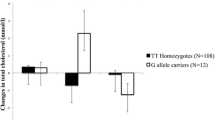

As expected (Huang et al. 2011), individuals with the Ala12Ala genotype had higher levels of HDL cholesterol and lower levels of LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein B at baseline (Table 1; Fig. 1a, P < 0.05, FDR < 0.01). Although we aimed to match individuals with the Pro12Pro and Ala12Ala genotypes for age and BMI, carriers with the Ala12Ala genotype were slightly older than carriers of the Pro12Pro genotype at baseline (P = 0.048, Table 1). No difference in glucose and insulin levels was observed between the genotypes. In Table 1, we also present the effects of the genotypes on serum lipids taking into account all time points during the study. In that analysis, total and LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein were associated with the genotype. More specifically, total and LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein were associated with the genotype at the end of the diets (P < 0.05).

Levels of serum triglycerides (mmol/l) are lower in individuals with the Ala12Ala genotype compared to individuals with the Pro12Pro genotype of PPARG at baseline (a) and lower in response to PUFA diet. The difference between genotypes was observed also after PUFA and SAFA diets (P < 0.01, not shown) (b). Mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001, t test at baseline

The Ala12Ala genotype was associated with higher adipose tissue expression of PPARG2 (Fig. 2a). Levels of adipose tissue PPARG2 mRNA expression were consistently higher in carriers of the Ala12Ala genotype than in carriers of the Pro12Pro genotype regardless of the diet (FDR = 0.001 for genotype effect in mixed-model analysis including all time points). In addition, expression of LPIN1 and SREBP-1c was higher in individuals with the Ala12Ala genotype (P = 0.009 and P = 0.032, respectively) (Fig. 2c, e). Expression of FASN did not associate with the genotype (P = 0.058) (Fig. 2g).

PPARG2 mRNA expression correlated negatively with serum total triglycerides at all three time points (all P < 0.05, Table 2, all time points combined in Supplementary Figure 1). We could not observe a significant difference in the correlation between PPARG2 mRNA expression and serum triglycerides between the genotypes (z = 0.71, P = 0.477, Fisher r-to-z transformation test, Supplementary Figure 1). There was an inverse correlation of PPARG2 mRNA expression with total and LDL cholesterol at 8 weeks but not at baseline or at the end of the study. There was no correlation between adipose tissue PPARG2 mRNA expression and the levels of glucose and insulin (data not shown).

PUFA diet improves lipid profile without affecting adipose tissue mRNA expression

Table 3 demonstrates a decrease in fasting glucose, total cholesterol, and total triglycerides in response to the PUFA diet (P < 0.05). In contrast, the SAFA diet led to a significant increase in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol (P < 0.05). Importantly, at the end of the dietary periods, the levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein B were higher after the SAFA diet compared to the PUFA diet (P < 0.05). To control for multiple testing and for the crossover setting, we also analyzed the data in a mixed model including diet, phase of the study, and the genotype. Diet had an effect on total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, total triglycerides, and apolipoprotein B (FDR < 0.1). The PUFA diet did not affect mRNA expression of PPARG2 (Fig. 2b), LPIN1 (Fig. 2d), SREBP-1c (Fig. 2f), FASN (Fig. 2h), ADIPOR1, and ADIPOR2 (data not shown). There was no interaction between the genotype and diet.

Discussion

In this study, we used a unique recruit-by-genotype approach to study the effect the Pro12Pro and Ala12Ala genotypes of PPARG on serum lipids in a dietary intervention trial. Similar approach has earlier been used to demonstrate an effect of the PPARG genotype on adipose metabolism (Tan et al. 2006). We demonstrated that the Ala12Ala genotype associated with lower levels of serum lipids at the baseline and at the end of the PUFA and SAFA diets and higher expression of PPARG2 mRNA in adipose tissue compared to the Pro12Pro genotype, independent of the diet (Figs. 1, 2; Table 1). In contrast, the PUFA diet improved serum lipids without affecting PPARG2 expression in adipose tissue. These results suggest that dietary PUFAs and the PPARG genotype regulate serum triglycerides through divergent pathways. More specifically, our results suggest that individuals with Pro12Pro genotype, with higher triglyceride levels, are more likely to benefit from the PUFA diet (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Our hypothesis was that the effects of the PUFA diet on glucose and lipid metabolism could depend on the PPARG genotype. This hypothesis was based on the knowledge that polyunsaturated fatty acids, including derivatives of DHA and EPA, are ligands for PPARG (Kliewer et al. 1997; Xu et al. 1999). Therefore, we assumed that the modification of the fatty acid composition in the diet changes the ligands, i.e., PUFAs, for PPARG and thus modifies PPARG2 function depending on the genotype. Given the low frequency of the Ala12Ala genotype in the population (<1 %), we recruited the participants with either the Pro12Pro or the Ala12Ala genotypes of PPARG from a large population-based METSIM cohort including 10,197 participants (Stancakova et al. 2009, 2012). However, there was no effect of the PUFA diet on the expression of PPARG2, and we could also not observe any diet–genotype interaction effect on PPARG2 expression. In addition, we did not observe any significant interaction in the effects of the PPARG genotype and the PUFA diet on serum lipids, or on glucose metabolism, which could be due to our small sample size. The correlation analysis between PPARG2 mRNA expression and serum triglycerides suggested a difference between genotypes (Supplementary Figure 1). More importantly, the beneficial effect of PUFA diet on serum triglycerides was observed in individuals with Pro12Pro genotype, with higher triglyceride levels at baseline. Together with the earlier findings that dietary fat intake correlates with the components with the metabolic syndrome in individuals with the Pro12Pro genotype but not in those with Ala12Ala genotype (Robitaille et al. 2003), our results suggest that although dietary effect on serum lipids is not mediated through PPARG2 mRNA expression in adipose tissue, PPARG genotype may still modify the effects of dietary fat on serum lipids.

The Ala12Ala genotype did associate with higher mRNA expression of PPARG2 which correlated with serum triglyceride levels. These results suggest that the effects of the PPARG genotype on serum lipid levels are mediated through altered PPARG2 expression in adipose tissue (Deeb et al. 1998), while the effect of the PUFA diet on serum triglyceride levels is independent of the PPARG genotype and PPARG2 expression in adipose tissue. The mechanisms how the Ala12 allele, which leads to lower transcriptional activity (Deeb et al. 1998) and associates with higher mRNA expression (Kolehmainen et al. 2003), contributes to lower levels of serum triglycerides remain unknown. However, these mechanisms may include secondary responses in adipose tissue, such as higher expression of LPIN1 and SREBP-1c and potential other targets. Secondary effects also outside the subcutaneous adipose tissue, e.g., in the visceral depot and in the liver, are possible, but cannot be investigated in a dietary intervention. We acknowledge that PCR-based gene expression analysis is always affected by the selection of endogenous control genes, and that the use of other control genes than RPLP0 could have slightly modified the results.

In summary, our study suggests that the beneficial effects of dietary PUFA and Ala12Ala genotype of PPARG on serum lipids are mediated through divergent pathways. Ultimately, larger randomized intervention trials based on genetic background will be needed to fully evaluate the significance of interactions between Pro12Ala polymorphism and environmental factors.

Abbreviations

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PPARG:

-

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma

- PUFA:

-

Polyunsaturated fatty acid

- SAFA:

-

Saturated fatty acid

- DHA:

-

Docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA:

-

Eicosapentaenoic acid

- ALA:

-

α-Linolenic acid

References

Agren JJ, Julkunen A, Penttila I (1992) Rapid separation of serum lipids for fatty acid analysis by a single aminopropyl column. J Lipid Res 33:1871–1876

Alsaleh A, O’Dell SD, Frost GS, Griffin BA, Lovegrove JA, Jebb SA, Sanders TA, RISCK Study investigators (2011) Interaction of PPARG Pro12Ala with dietary fat influences plasma lipids in subjects at cardiometabolic risk. J Lipid Res 52:2298–2303

AlSaleh A, Sanders TA, O’Dell SD (2012) Effect of interaction between PPARG, PPARA and ADIPOQ gene variants and dietary fatty acids on plasma lipid profile and adiponectin concentration in a large intervention study. Proc Nutr Soc 71:141–153

Altshuler D, Hirschhorn JN, Klannemark M, Lindgren CM, Vohl MC, Nemesh J, Lane CR, Schaffner SF, Bolk S, Brewer C, Tuomi T, Gaudet D, Hudson TJ, Daly M, Groop L, Lander ES (2000) The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 26:76–80

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 57:289–300

Bouchard-Mercier A, Godin G, Lamarche B, Perusse L, Vohl MC (2011) Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, dietary fat intakes and gene-diet interactions on peak particle diameters of low-density lipoproteins. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics 4:36–48

Cornelis MC, Hu FB (2012) Gene-environment interactions in the development of type 2 diabetes: recent progress and continuing challenges. Annu Rev Nutr 32:245–259

Deeb S, Fajas L, Nemoto M, Pihlajamäki J, Mykkänen L, Kuusisto J, Laakso M, Fujimoto W, Auwerx J (1998) A Pro12Ala substitution in the human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma 2 is associated with decreased receptor activity, lower body mass index and improved insulin sensitivity. Nat Genet 20:284–287

Ek J, Urhammer S, Sörensen T, Andersen T, Auwerx J, Pedersen O (1999) Homozygosity of the Pro12Ala variant of the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor-gamma2 (PPAR-gamma2): divergent modulating effects on body mass index in obese and lean Caucasian men. Diabetologia 42:892–895

Garaulet M, Smith CE, Hernandez-Gonzalez T, Lee YC, Ordovas JM (2011) PPARgamma Pro12Ala interacts with fat intake for obesity and weight loss in a behavioural treatment based on the Mediterranean diet. Mol Nutr Food Res 55:1771–1779

Heikkinen S, Argmann C, Feige JN, Koutnikova H, Champy MF, Dali-Youcef N, Schadt EE, Laakso M, Auwerx J (2009) The Pro12Ala PPARgamma2 variant determines metabolism at the gene-environment interface. Cell Metab 9:88–98

Huang X, Zhao J, Zhao T (2011) Effects of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-gamma 2 gene Pro12Ala polymorphism on fasting blood lipids: a meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 215:136–144

Huyghe JR, Jackson AU, Fogarty MP, Buchkovich ML, Stancakova A, Stringham HM, Sim X, Yang L, Fuchsberger C, Cederberg H, Chines PS, Teslovich TM, Romm JM, Ling H, McMullen I, Ingersoll R, Pugh EW, Doheny KF, Neale BM, Daly MJ, Kuusisto J, Scott LJ, Kang HM, Collins FS, Abecasis GR, Watanabe RM, Boehnke M, Laakso M, Mohlke KL (2012) Exome array analysis identifies new loci and low-frequency variants influencing insulin processing and secretion. Nat Genet

Karvonen HM, Aro A, Tapola NS, Salminen I, Uusitupa MI, Sarkkinen ES (2002) Effect of alpha-linolenic acid-rich Camelina sativa oil on serum fatty acid composition and serum lipids in hypercholesterolemic subjects. Metabolism 51:1253–1260

Kliewer SA, Sundseth SS, Jones SA, Brown PJ, Wisely GB, Koble CS, Devchand P, Wahli W, Willson TM, Lenhard JM, Lehmann JM (1997) Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:4318–4323

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, Nathan DM (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Kolehmainen M, Uusitupa MI, Alhava E, Laakso M, Vidal H (2003) Effect of the Pro12Ala polymorphism in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma2 gene on the expression of PPARgamma target genes in adipose tissue of massively obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:1717–1722

Lindi VI, Uusitupa MI, Lindstrom J, Louheranta A, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Tuomilehto J (2002) Association of the Pro12Ala polymorphism in the PPAR-gamma2 gene with 3-year incidence of type 2 diabetes and body weight change in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Diabetes 51:2581–2586

Luan J, Browne PO, Harding AH, Halsall DJ, O’Rahilly S, Chatterjee VK, Wareham NJ (2001) Evidence for gene-nutrient interaction at the PPARgamma locus. Diabetes 50:686–689

Manolio TA, Collins FS, Cox NJ, Goldstein DB, Hindorff LA, Hunter DJ, McCarthy MI, Ramos EM, Cardon LR, Chakravarti A, Cho JH, Guttmacher AE, Kong A, Kruglyak L, Mardis E, Rotimi CN, Slatkin M, Valle D, Whittemore AS, Boehnke M, Clark AG, Eichler EE, Gibson G, Haines JL, Mackay TF, McCarroll SA, Visscher PM (2009) Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature 461:747–753

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470

Medina-Gomez G, Virtue S, Lelliott C, Boiani R, Campbell M, Christodoulides C, Perrin C, Jimenez-Linan M, Blount M, Dixon J, Zahn D, Thresher RR, Aparicio S, Carlton M, Colledge WH, Kettunen MI, Seppanen-Laakso T, Sethi JK, O’Rahilly S, Brindle K, Cinti S, Oresic M, Burcelin R, Vidal-Puig A (2005) The link between nutritional status and insulin sensitivity is dependent on the adipocyte-specific peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 isoform. Diabetes 54:1706–1716

Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, Ferreira T, Segre AV, Steinthorsdottir V, Strawbridge RJ, Khan H, Grallert H, Mahajan A, Prokopenko I, Kang HM, Dina C, Esko T, Fraser RM, Kanoni S, Kumar A, Lagou V, Langenberg C, Luan J, Lindgren CM, Muller-Nurasyid M, Pechlivanis S, Rayner NW, Scott LJ, Wiltshire S, Yengo L, Kinnunen L, Rossin EJ, Raychaudhuri S, Johnson AD, Dimas AS, Loos RJ, Vedantam S, Chen H, Florez JC, Fox C, Liu CT, Rybin D, Couper DJ, Kao WH, Li M, Cornelis MC, Kraft P, Sun Q, van Dam RM, Stringham HM, Chines PS, Fischer K, Fontanillas P, Holmen OL, Hunt SE, Jackson AU, Kong A, Lawrence R, Meyer J, Perry JR, Platou CG, Potter S, Rehnberg E, Robertson N, Sivapalaratnam S, Stancakova A, Stirrups K, Thorleifsson G, Tikkanen E, Wood AR, Almgren P, Atalay M, Benediktsson R, Bonnycastle LL, Burtt N, Carey J, Charpentier G, Crenshaw AT, Doney AS, Dorkhan M, Edkins S, Emilsson V, Eury E, Forsen T, Gertow K, Gigante B, Grant GB, Groves CJ, Guiducci C, Herder C, Hreidarsson AB, Hui J, James A, Jonsson A, Rathmann W, Klopp N, Kravic J, Krjutskov K, Langford C, Leander K, Lindholm E, Lobbens S, Mannisto S, Mirza G, Muhleisen TW, Musk B, Parkin M, Rallidis L, Saramies J, Sennblad B, Shah S, Sigurethsson G, Silveira A, Steinbach G, Thorand B, Trakalo J, Veglia F, Wennauer R, Winckler W, Zabaneh D, Campbell H, van Duijn C, Uitterlinden AG, Hofman A, Sijbrands E, Abecasis GR, Owen KR, Zeggini E, Trip MD, Forouhi NG, Syvanen AC, Eriksson JG, Peltonen L, Nothen MM, Balkau B, Palmer CN, Lyssenko V, Tuomi T, Isomaa B, Hunter DJ, Qi L, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related traits Consortium (MAGIC) Investigators, Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium, Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network-Type 2 Diabetes (AGEN-T2D) Consortium, South Asian Type 2 Diabetes (SAT2D) Consortium, Shuldiner AR, Roden M, Barroso I, Wilsgaard T, Beilby J, Hovingh K, Price JF, Wilson JF, Rauramaa R, Lakka TA, Lind L, Dedoussis G, Njolstad I, Pedersen NL, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi SM, Saaristo TE, Korpi-Hyovalti E, Saltevo J, Laakso M, Kuusisto J, Metspalu A, Collins FS, Mohlke KL, Bergman RN, Tuomilehto J, Boehm BO, Gieger C, Hveem K, Cauchi S, Froguel P, Baldassarre D, Tremoli E, Humphries SE, Saleheen D, Danesh J, Ingelsson E, Ripatti S, Salomaa V, Erbel R, Jockel KH, Moebus S, Peters A, Illig T, de Faire U, Hamsten A, Morris AD, Donnelly PJ, Frayling TM, Hattersley AT, Boerwinkle E, Melander O, Kathiresan S, Nilsson PM, Deloukas P, Thorsteinsdottir U, Groop LC, Stefansson K, Hu F, Pankow JS, Dupuis J, Meigs JB, Altshuler D, Boehnke M, McCarthy MI, DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium (2012) Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet 44:981–990

Pihlajamaki J, Vanhala M, Vanhala P, Laakso M (2004) The Pro12Ala polymorphism of the PPAR gamma 2 gene regulates weight from birth to adulthood. Obes Res 12:187–190

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team (2015) nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-122. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme

Robitaille J, Despres JP, Perusse L, Vohl MC (2003) The PPAR-gamma P12A polymorphism modulates the relationship between dietary fat intake and components of the metabolic syndrome: results from the Quebec Family Study. Clin Genet 63:109–116

Sandholt CH, Hansen T, Pedersen O (2012) Beyond the fourth wave of genome-wide obesity association studies. Nutr Diabetes 2:e37

Stancakova A, Javorsky M, Kuulasmaa T, Haffner SM, Kuusisto J, Laakso M (2009) Changes in insulin sensitivity and insulin release in relation to glycemia and glucose tolerance in 6,414 Finnish men. Diabetes 58:1212–1221

Stancakova A, Civelek M, Saleem NK, Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Cederberg H, Paananen J, Pihlajamaki J, Bonnycastle LL, Morken MA, Boehnke M, Pajukanta P, Lusis AJ, Collins FS, Kuusisto J, Ala-Korpela M, Laakso M (2012) Hyperglycemia and a common variant of GCKR are associated with the levels of eight amino acids in 9,369 Finnish men. Diabetes 61:1895–1902

Tan GD, Neville MJ, Liverani E, Humphreys SM, Currie JM, Dennis L, Fielding BA, Karpe F (2006) The in vivo effects of the Pro12Ala PPARgamma2 polymorphism on adipose tissue NEFA metabolism: the first use of the Oxford Biobank. Diabetologia 49:158–168

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, Keinanen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Rastas M, Salminen V, Uusitupa M (2001) Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 344:1343–1350

Uusitupa M (2005) Gene-diet interaction in relation to the prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes: evidence from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 15:225–233

Vessby B, Lithell H, Gustafsson IB, Boberg J (1980) Changes in the fatty acid composition of the plasma lipid esters during lipid-lowering treatment with diet, clofibrate and niceritrol. Reduction of the proportion of linoleate by clofibrate but not by niceritrol. Atherosclerosis 35:51–65

Vidgren HM, Agren JJ, Schwab U, Rissanen T, Hanninen O, Uusitupa MI (1997) Incorporation of n-3 fatty acids into plasma lipid fractions, and erythrocyte membranes and platelets during dietary supplementation with fish, fish oil, and docosahexaenoic acid-rich oil among healthy young men. Lipids 32:697–705

Xu HE, Lambert MH, Montana VG, Parks DJ, Blanchard SG, Brown PJ, Sternbach DD, Lehmann JM, Wisely GB, Willson TM, Kliewer SA, Milburn MV (1999) Molecular recognition of fatty acids by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Mol Cell 3:397–403

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaija Kettunen, Tuomas Onnukka, Päivi Turunen, and Sirkku Karhunen for their careful work in patient recruitment and laboratory analyses; Taisa Venäläinen for instructing the subjects and analyzing dietary intake; and Marketta Puttonen for practical assistance during the study.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Kuopio University Hospital (JPI, EVO project); the Academy of Finland (Contract No. 138006 JPI, 124243 ML and 141069 ML/MU); the Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation (JPI, MU, and ML); the Finnish Heart Foundation (ML); TEKES (ML, Contract No. 1510/31/06); and Commission of the European Community (ML, Contract No. LSHM-CT-2004-512013 EUGENE2). We thank Skånemejerier Ltd, Maitokolmio cooperative, Riitan Herkku Ltd, and Bunge Finland Ltd. for providing food items.

Authorship

JPI designed the research, analyzed data, wrote paper, and had primary responsibility for final content. US was responsible for planning the diets, conduction of the dietary intervention, supervision of nutrient intake calculations and data entering, and analyzed data. DK conducted RNA analyses, analyzed data, and participated in writing the paper. JÅ was responsible for the fatty acid composition analysis. MK contributed to the study design and discussion. JPA was responsible for the statistical analysis. ML and JK are responsible for the METSIM study and contributed to statistical analyses and discussion. MU was responsible for the study design with JPI and contributed to the analysis and discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Jussi Pihlajamäki, Ursula Schwab, Dorota Kaminska, Jyrki Ågren, Johanna Kuusisto, Marjukka Kolehmainen, Jussi Paananen, Markku Laakso, and Matti Uusitupa declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

In this study protocol, all procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the Northern Savo Hospital District (28/2010; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01274091) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pihlajamäki, J., Schwab, U., Kaminska, D. et al. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and the Pro12Ala polymorphisms of PPARG regulate serum lipids through divergent pathways: a randomized crossover clinical trial. Genes Nutr 10, 43 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-015-0493-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-015-0493-z