Abstract

There are around 2,500 new cases of oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) reported yearly within Australia. Resection often leads to substantial defects, requiring complex reconstruction. The aim of this study was to examine how reconstruction at a dedicated head and neck cancer unit has evolved over a 30-year period. A retrospective review was conducted of all OSCC carcinoma cases performed from 1988 to 2017. Data was analysed in six-time periods; pre-1995, 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009, 2010–2014, and 2015 and above. A total of 903 patients were identified, of which 56.1% (n = 507) underwent free flap reconstruction including 426 (84.0%) soft tissue free flaps (STFF) and 81 (16.0%) bony free flaps (BFF). STFF usage remained stable over time. The radial forearm was the most common free flap but declined over time with increasing use of the anterolateral thigh flap. The number of BFF increased from 5.0% before 1995 to 20.4% in 1995–2015. The tongue was the most common subsite, followed by the floor of mouth. Free flaps were utilised in more than 50% of OSCC reconstructions at each time period. Over time, the proportion of different STFF evolved towards increased use of the ALT flap and BFF within our institution. Level of evidence: Level four.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common mucosal malignancy in the head and neck region, accounting for over 300,000 new cases globally in 2012 [1]. It is the 11th most common cancer worldwide, and approximately 30% of those affected will die of locoregional recurrence or distant metastases [2]. Common risk factors for the development of OSCC include smoking, alcohol consumption, and betel nut chewing [3]. Whilst the incidence of OSCC is declining overall, there has been an increase in incidence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the mobile tongue in young adults [4, 5]. The driving mechanisms behind this increase remain unclear [6].

The mainstay of treatment for OSCC is surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy [7]. Patients often require wide surgical resections that result in large defects. Reconstructive surgery is used to optimise healing, assist speech and swallowing, and improve aesthetic outcomes [8]. The choice of closure is largely dependent on the size of the surgical defect, location of the resected primary, and type of tissue required, as well as institutional and patient factors. Options range from primary closure, local flaps, and regional flaps to free flaps [9]. Microvascular free tissue transfer is the preferred approach for large and complex surgical defects. With advances in microvascular surgery, more radical operations for larger tumours have become possible, with improvements in oncological outcomes and quality of life [10,11,12]. The aim of this paper is to review the choice of reconstruction for oral cavity defects over a 30-year period at a quaternary head and neck referral centre.

Methods

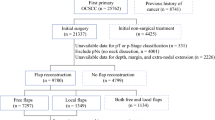

Ethics for this project were approved by the Sydney Local Health District (SLHD Ethics Protocol No X16-0367). Historical patient records from the Sydney Head and Neck Cancer database were analysed, searching for all oral cavity resections for OSCC performed at our institution between 1988 and 2018. The cases were grouped in 5-year block: “pre-1995”, “1995–1999”, “2000–2004”, “2005–2009”, “2010–2014”, and “post-2015”. Information regarding age, sex, stage, location of cancer, and type of reconstruction was extracted.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM, Armonk, New York). Categorical variables and trends over time were compared with chi-square test.

Results

There were 903 patients identified, including 553 males (61.2%) and 350 females (38.8%). The median age was 63.7 years (IQR = 53.6–72.8 years). The most common subsite was the oral tongue (43.4%, n = 392) (Table 1), followed by floor of mouth (25.2%, n = 228). The hard palate was the least common subsite with only 15 cases (1.7%). Over time, there was a non-significant increase in the number of cases involving the alveolus and hard palate (p = 0.092). The number and percentage of floor of mouth declined, from 45 (32.4%) in pre-1995 to 20 (18.5%) in the 2015 and above group (p < 0.05).

Cancer staging was recorded for 851 of the 903 cases in the series. The most common T category was T2 (35.9%), followed by T1 (31.4%), T4 (21.9%), and finally, T3 (10.8%). T1 tumours were closed primarily in 71.3% (n = 191) of cases. T2 to T4 tumours were most frequently closed with soft tissue free flaps, ranging from 51.8% of T4 tumours to 82.2% of T3 tumours. Bone flaps were only used for T4 tumours, with 40.8% of T4 tumours closed utilising bone containing free flaps. Bone flaps included the fibular free flap, osteocutaneous lateral scapula flaps, deep circumflex iliac bone flaps, and in one case, a radial bone containing forearm free flap.

Microvascular free flap reconstruction was used in 56.1% of all cases (n = 507), of which soft tissue free flaps (STFF) accounted for 84.0% (n = 426) and bony free flaps (BFF) accounted for the remaining 16.0% (n = 81). Local and regional flaps were used in 9.7% (n = 63), and primary closure was used in 33.6% (n = 303). The proportion of patients undergoing free flap reconstruction remained stable from 1995 to 2014 between 51 and 57% but increased to 78% after 2015. BFF increased over time from 5.0% pre-1995 to 20.4% post-2015 (p < 0.001), whilst the use of STFF remained between 40.1 and 54.5% for each time-period (Table 2).

The choice of free flaps over this period is presented in Fig. 1. The most common STFF overall was the radial forearm free flap (RFFF) at 67.1% (n = 340). However, there was a steady decline in the use of RFFF over time (p < 0.001) from 89.7% pre-2005 to 46.4% after 2005. The variety of free flaps expanded during the 2005–2009 period, including the anterolateral thigh flap (ALT), ulnar forearm free flap superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap, medial sural flap, gastro-omental flap, and free flaps of the subscapular axis.

Choice of free flaps at a dedicated head and neck unit over a 30-year period. RFFF, radial forearm free flap; ALT, anterolateral thigh; UFFF, ulnar forearm free flap. Other flaps include the superficial circumflex iliac artery perforator (SCIP) flap, medial sural flap, gastro-omental flap, and free flaps of the subscapular axis

For the two most common subsites, the tongue and the floor of mouth, we investigated the different reconstructive approaches used over time (Table 3). There were 392 cases of oral tongue SCC and 223 cases of floor of mouth SCC. Over half of the tongue defects were reconstructed with primary closure (52.8%, n = 207), whilst most floor of mouth defects were reconstructed utilising free flaps (73.2%, n = 167). Over time, the type of free flap reconstruction remained relatively constant (p = 0.90 and p = 0.86, respectively). The most popular free flap for the tongue was the RFFF, with increasing use of the ALT in later time periods. A similar trend was noted for floor of mouth reconstruction.

Tumour stage and reconstructive choice was analysed for the tongue and floor of mouth (Table 4). As the T category increased, STFFs became more prevalent, used in 83.3% of T3 and 75% of T4 tongue tumours. T1 tongue cancers were mainly closed with primary closure (85.7%). For floor of mouth, T1 tumours were reconstructed mainly with either primary closure (42%) or STFFs (30%). STFFs were used in 81.4% of T2 and 72.2% T3 tumours. BFFs were used in 50.0% of T4 floor of mouth tumours.

Discussion

This study describing the trends in oral cancer reconstruction in 903 patients over a 30-year period is the largest published single centre series in Australia. Over time, we observe BFF reconstructions were used more frequently and the RFFF was used less often.

The tongue is the most common subsite of oral cancer, representing 43.4% of all cases in this series (Table 1), consistent with international studies [13,14,15,16]. The tongue is a mobile structure with tissue suitable for primary closure, especially for early lesions, with resections up to 30% able to be closed primarily without significant impairment on swallow and speech intelligibility [17]. In keeping with this, around half of all oral tongue defects were repaired with primary closure in this series (Table 3). Smaller lesions in the gingivobuccal sulcus also are amenable to this. In contrast, primary closure of tumours occurring in the floor of mouth leads to tethering of the tongue to the mandible and loss of the normal lingual sulcus causing functional impairment. For this reason, free flaps are often used to reconstruct defects in this region [18, 19] and were used in 73.2% of all floor mouth cases in this series.

The ALT free flap is well known for its versatility in head and neck reconstruction and the ability to close the donor site primarily [20]. The ALT was first described by Song et al. [21] and was shown to have comparable outcomes to the RFFF with less donor site morbidity, whilst still maintaining a two-team approach [22,23,24]. The above benefits, combined with improved training for perforator dissection [25, 26] and increased international trends towards microvascular reconstruction as a standard component of head and neck surgical training [27, 28], are likely responsible for the increasing use of the ALT free flap for oral reconstruction. This is seen in Fig. 1, where decreasing use of the RFFF was noted with replacement mainly by the ALT after the 2005–2009 period. Tension-free closure and tailored volume restoration achieved by free flaps often results in better functional outcomes [19] as well as improvements in quality of life [9,10,11,12]. Of relevance, the ALT is particularly useful in volume restoration, being less suited to smaller defects. This is likely reflected in Table 4 with larger proportions of soft tissue free flaps used for more advanced tongue tumours. This is in comparison to centres in India, where the pectoralis major myocutaneous flap remains the workhorse, with one series identifying it used for 60% of all flaps for oral cancer reconstruction [29].

The use of free flaps has remained relatively stable between the pre-1995 group and the 2010–2014 group at 51%–57% of oral cavity reconstructions. However, from 2015 onwards, the use of free flaps increased to 72.2%, mainly due to a rise in the number of BFFs (Table 2). Over this period, we also noted an increase in T4 tumours, and alveolar or hard palate tumours referred to our centre (Table 1). Whilst there is no evidence of increased incidence in alveolar or hard palate malignancies globally [30], our unit has a special interest in mandibular and maxillary reconstruction, with a multidisciplinary team established to provide dental and prosthetic rehabilitation utilising complex 3D modelling [31, 32]. This increase likely reflects a referral bias to our unit given this focus of our unit. We have shown excellent dental rehabilitation within these cases and with increasing experience in the use of zygomatic implant perforated free flaps, the requirement for BFF maxillary reconstruction may decrease in time.

Limitations

This is a single-centre series of a dedicated head and neck referral centre over a 30-year period. As such, observations should not be generalised to reflect trends in the wider society. Our observations may reflect referral bias and biases in practices of appointment of staff to the unit. Changes in staff over time could also impact with changes in surgical preference, such as our increased focus on virtual surgical planning and dental rehabilitation for oromandibular pathology.

Conclusion

The choice for reconstruction of oral cavity lesions at our institution have changed over a 30-year period, incorporating more BFFs. The choice of STFF has also changed, with increasing use of the ALT free flap replacing the RFFF. It is likely our trend to free flap utilisation will remain given current referral patterns to our centre.

References

Bray F, Ren JS, Masuyer E, Ferlay J (2013) Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer 132(5):1133–1145

Ahmadi N, Gao K, Chia N, Kwon MS, Palme CE, Gupta R et al (2019) Association of PD-L1 expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma with smoking, sex, and p53 expression. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 128(6):631–638

Gupta N, Gupta R, Acharya AK, Patthi B, Goud V, Reddy S et al (2016) Changing trends in oral cancer - a global scenario. Nepal J Epidemiol 6(4):613–619

Patel SC, Carpenter WR, Tyree S, Couch ME, Weissler M, Hackman T et al (2011) Increasing incidence of oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma in young white women, age 18 to 44 years. J Clin Oncol 29(11):1488–1494

Oliver RJ, Dearing J, Hindle I (2000) Oral cancer in young adults: report of three cases and review of the literature. Br Dent J 188(7):362–366

Mohideen K, Krithika C, Jeddy N, Bharathi R, Thayumanavan B, Sankari SL (2019) Meta-analysis on risk factors of squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue in young adults. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 23(3):450–457

Wolff KD, Follmann M, Nast A (2012) The diagnosis and treatment of oral cavity cancer. Dtsch Arztebl Int 109(48):829–835

Kolokythas A. Long-term surgical complications in the oral cancer patient: a comprehensive review. Part I. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2010;1(3):e1.

Hartig GK (2007) Free flaps in oral cavity reconstruction: when you need them and when you don’t. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 69(2 Suppl):S19-21

Hanasono MM, Friel MT, Klem C, Hsu PW, Robb GL, Weber RS et al (2009) Impact of reconstructive microsurgery in patients with advanced oral cavity cancers. Head Neck 31(10):1289–1296

Villaret AB, Cappiello J, Piazza C, Pedruzzi B, Nicolai P (2008) Quality of life in patients treated for cancer of the oral cavity requiring reconstruction: a prospective study. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 28(3):120–125

de Vicente JC, Rodriguez-Santamarta T, Rosado P, Pena I, de Villalain L (2012) Survival after free flap reconstruction in patients with advanced oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70(2):453–459

Auluck A, Hislop G, Bajdik C, Poh C, Zhang L, Rosin M (2010) Trends in oropharyngeal and oral cavity cancer incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-related and HPV-unrelated sites in a multicultural population: the British Columbia experience. Cancer 116(11):2635–2644

Elwood JM, Youlden DR, Chelimo C, Ioannides SJ, Baade PD (2014) Comparison of oropharyngeal and oral cavity squamous cell cancer incidence and trends in New Zealand and Queensland. Australia Cancer Epidemiol 38(1):16–21

Krishna Rao SV, Mejia G, Roberts-Thomson K, Logan R (2013) Epidemiology of oral cancer in Asia in the past decade–an update (2000–2012). Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 14(10):5567–5577

Weatherspoon DJ, Chattopadhyay A, Boroumand S, Garcia I (2015) Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer incidence trends and disparities in the United States: 2000–2010. Cancer Epidemiol 39(4):497–504

McConnel FM, Pauloski BR, Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Colangelo L, Shedd D, et al. (1998) Functional results of primary closure vs flaps in oropharyngeal reconstruction: a prospective study of speech and swallowing. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 124(6):625–30.

Vincent A, Kohlert S, Lee TS, Inman J, Ducic Y (2019) Free-flap reconstruction of the tongue. Semin Plast Surg 33(1):38–45

Ji YB, Cho YH, Song CM, Kim YH, Kim JT, Ahn HC, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after resection of tongue cancer: determining the optimal reconstruction method. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2017;274(10):3751–6.

Park CW, Miles BA (2011) The expanding role of the anterolateral thigh free flap in head and neck reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 19(4):263–268

Song YG, Chen GZ, Song YL (1984) The free thigh flap: a new free flap concept based on the septocutaneous artery. Br J Plast Surg 37(2):149–159

Chien CY, Su CY, Hwang CF, Chuang HC, Jeng SF, Chen YC (2006) Ablation of advanced tongue or base of tongue cancer and reconstruction with free flap: functional outcomes. Eur J Surg Oncol 32(3):353–357

Camaioni A, Loreti A, Damiani V, Bellioni M, Passali FM, Viti C. Anterolateral thigh cutaneous flap vs. radial forearm free-flap in oral and oropharyngeal reconstruction: an analysis of 48 flaps. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica: organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2008;28(1):7–12.

Chen H, Zhou N, Huang X, Song S (2016) Comparison of morbidity after reconstruction of tongue defects with an anterolateral thigh cutaneous flap compared with a radial forearm free-flap: a meta-analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54(10):1095–1101

Chang CC, Shen JH, Chan KK, Wei FC (2016) Selection of ideal perforators and the use of a free-style free flap during dissection of an anterolateral thigh flap for reconstruction in the head and neck. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 54(7):830–832

Wong CH, Wei FC (2010) Anterolateral thigh flap. Head Neck 32(4):529–540

Bennion DM, Dziegielewski PT, Boyce BJ, Ducic Y, Sawhney R (2019) Fellowship training in microvascular surgery and post-fellowship practice patterns: a cross sectional survey of microvascular surgeons from facial plastic and reconstructive surgery programs. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 48(1):19

Spiegel JH, Polat JK (2007) Microvascular flap reconstruction by otolaryngologists: prevalence, postoperative care, and monitoring techniques. Laryngoscope 117(3):485–490

Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti PR, Desai SM, Agrawal D, Mehta DY, Pancholi M (2015) Reconstruction in oral malignancy: factors affecting morbidity of various procedures. Annals of maxillofacial surgery 5(2):191–197. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0746.175748

Ellington TD, Henley SJ, Senkomago V, O’Neil ME, Wilson RJ, Singh S et al (2020) Trends in incidence of cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx - United States 2007–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69(15):433–438

Diab J, Leinkram D, Wykes J, Cheng K, Wallace C, Howes D et al (2021) Maxillofacial reconstruction with prefabricated prelaminated osseous free flaps. ANZ J Surg 91(3):430–438

Leinkram D, Wykes J, Palme C, Deshpande S, McLaughlin M, Garg P et al (2021) Occlusal-based planning for dental rehabilitation following segmental resection of the mandible and maxilla. ANZ J Surg 91(3):451–452

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayler, R., Sudirman, S.R., Clark, J. et al. Oral Cavity Reconstruction over a 30-Year Period at a Dedicated Tertiary Head and Neck Cancer Centre. Indian J Surg 85, 33–38 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-022-03336-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-022-03336-0