Abstract

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) leads to metastatic disease in approximately 30% of patients. In patients with newly diagnosed CRC with both liver and lung metastases, curative resection is rarely possible. The aim of this study is to evaluate the overall (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) rates of these patients after resection with curative intent.

Methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of colorectal cancer patients (n=8, median age 54.3 years) with simultaneous liver and lung metastasis undergoing resection with curative intent between May 1st, 2002, to December 31st, 2016, at our institution.

Results

Colon was the primary tumour site in 2 patients and rectum in 6 patients. The median number of liver and lung metastases was 3 and 2, respectively. Patients received various treatment sequences individualized on tumour disease burden. R0 resection was achieved after all but one procedure. Two severe Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb complications were present. Median hospital stay was 9 (3–24) days per procedure. Tumour relapse was observed in all patients with median RFS of 9 (3–28) months and median OS of 40 (17–52) months. In 4 cases, where repeated resection of recurrent metastases (3 liver and 1 lung) was possible, the median OS was 43 months.

Conclusion

Our data suggests that patients seem to benefit from resection with curative intent, with tendency to prolonged OS and with acceptable complication rate. Tumour recurrence occurred in all patients. Repeated resection was beneficial and led to further prolonged OS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) leads to metastatic disease in approximately 30% of patients. The liver and lung are the most frequent sites of metastatic spread in these patients [1, 2]. CRC with synchronous metastasis has an unfavourable prognosis, and the overall survival (OS) is reduced in comparison to metachronous metastases (5-year OS of 39% vs 48%) [3]. Moreover is the definition of “synchronous” broadly used for metastases detected in different period reaching up to 12 months after detection of the primary CRC. However, resection of solitary liver or lung metastases promises a survival benefit, and resection should be considered in these patients [3,4,5,6].

Up to 42% of patients with liver metastases also develop lung metastases. In patients with metachronous liver and lung metastases, resection of metastases is a well-established strategy leading to prolonged survival or even potential cure in some cases [7]. However, the increased number of metastases as well as the sites of the metastatic spread means more systemic disease and decreases the chance for curative resection while also leading to a worse overall prognosis [3, 4, 8].

Despite substantial improvement of oncological therapy through recent years, the combination of oncological therapy with radical surgical treatment remains the only potentially curative strategy [9]. The presence of a newly diagnosed CRC with simultaneous liver and lung metastases which would be possibly radical resectable is rare and the data are scarce [7, 9,10,11,12]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the overall and relapse-free survival rates of patients after resection of truly simultaneously detected hepatic and pulmonary metastases synchronous with primary CRC with curative intent at our centre.

Patients and Methods

Study Cohort

This study is a retrospective analysis from our prospectively maintained lung and liver operation database. The data from all patients undergoing lung resection for colorectal cancer metastases between May 1st, 2002, to December 31st, 2016, at the surgical department of Paracelsus Medical University in Salzburg, Austria, were reviewed. We then identified the patients who had also undergone resection of hepatic metastases. The subgroup of patients with simultaneous liver and lung metastases synchronous with primary tumour was evaluated. The study was performed according to the criteria of the ethics committee of the state of Salzburg.

Indication for Resection

During the preoperative investigation, an endoscopic diagnostic procedure with biopsy and histological verification of the primary tumour as well as a computed tomography of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was performed. PET scan was not standardly used for diagnosis. The levels of the tumour marker carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) were tested in blood samples.

The indication for resection was made on an individual basis and depended on the likelihood to achieve R0 resection for the primary tumour and all metastases, sufficient liver remnant volume after the liver resection, and sufficient cardio-pulmonary function for the planned lung resection.

Patients with non-curative resection of the primary tumour or liver as well as lung metastases or any diagnosis of other than liver and lung site metastases were excluded from analysis.

The surgical resection of the primary site was performed using standard oncological principles of colorectal surgery. Additionally, metastasectomy with the intention of R0 resection was performed.

Definition

Synchronous metastases were defined as lesions detected at the same time or before the diagnosis of primary colorectal cancer [3]. A metachronous metastasis was defined as metastases detected thereafter. Simultaneous metastases were designated as lesions detected at the same time or within 3 months of each other.

Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time after resection of all tumour sites to any new occurrence of the same cancer. The cancer-specific survival was defined as the time until death caused by the same cancer. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the period from the first tumour diagnosis to the patient’s death, irrespective of cause [13].

Follow-Up

The postoperative follow-up of the patients was performed according to current guidelines for management of colorectal cancer as follows: during the first 2 postoperative years, patients underwent clinical examination, computed tomography of chest and abdomen, and CEA testing every 3 months and, after that, every half a year until 5 years postoperatively. Data regarding tumour recurrence and survival were retrieved from FileMaker Pro database (FileMaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). For the further processing were data pseudo anonymised and saved in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Inc., Redmond, WA, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) computer program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as median, range, minimum, maximum, or percentage. Prognosis was calculated including all types of mortality beginning at the date of diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier plots were used to describe survival distribution. Data are presented as median values (minimum-maximum). The statistical analysis of overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) was estimated as a percentage.

Results

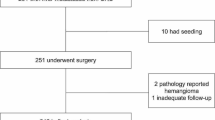

During the study period, 171 colorectal cancer patients had undergone surgery for liver metastases, 64 resection for lung metastases, and 19 for liver and lung metastases. In 8 patients, liver and lung metastases were diagnosed simultaneously and synchronously with a primary tumour. The median age of these patients at diagnosis was 54.3 years (5 female and 3 male). Demographic data and results are presented in Table 1. Decision of treatment and resection strategy was made on individual basis by possible R0 resection of all metastases in biologically fit patients in interdisciplinary agreement in our weekly tumour board. The sequence of resections is shown in Graph 1.

Primary Tumour

The primary tumour was in the colon in 2 patients and in the rectum in 6 patients. The resection of primary tumour was performed as the first line in 1 patient. Simultaneous colorectal and liver resections were performed in 4 patients, and in 3 patients, the primary resection was performed after metastasectomy. A radical resection with lymphadenectomy according to standard oncological principles of colorectal surgery was performed in all patients. The histological analyses revealed adenocarcinoma in 7 cases and goblet cell carcinoma in 1 patient. KRAS analysis was performed in 5 patients, and mutation was detected in 3 cases (one KRAS exon 2 and two KRAS codon 12/13 mutations) and MSI analysis in 2 cases (one MSI high, one MSS). HNPCC was not present in our cohort. Median hospital stay was 11 (6–20) days. There was no 30-day mortality. There was one grade IIIb morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo scoring in patient who developed anastomosis insufficiency.

Liver Resection

The primary resection was the first surgical step in one patient, with subsequent liver metastasectomy performed after 13 months. The liver metastases were resected as a liver first concept in 3 patients with advanced liver findings and the risk of becoming not resectable. The time span between liver metastasectomy and primary resection were 2, 3 and 3 months. Simultaneous colorectal and liver resections were performed in 4 patients. An atypical resection was performed in 5 patients, and segmentectomy was performed in 2 patients. One hemihepatectomy with subsequent atypical resection was performed as a staged resection. There was additional ablative therapy performed in 2 patients with atypical resection. The median number of metastases was 3 (min 1, max 20). There were simultaneous liver and lung resections performed in 1 patient. R0 resection was achieved in all patients. Median hospital stay was 9 (6–24) days. There was no 30-day mortality. There was one grade IIIa morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo scoring in a patient who developed biliary leak and was percutaneously drained.

Lung Resection

One lung resection was performed as the primary surgical therapy as well as diagnostic approach for neoadjuvant treatment with subsequent simultaneous colorectal and liver resection after 3 months. One simultaneous liver and lung resection was performed 13 months after resection of the rectum. The time periods between the liver and lung metastasectomy were 1, 2, 2, 4, 10 and 25 months. All patients were treated with either a wedge or segment resection. Video-assisted thoracoscopic resection (VATS) was performed in 4 patients. The median number of metastases was 2 (min 1, max 3), and there was bilateral disease present in 2 patients. R0 resection was achieved in all but one patient. Median hospital stay was 5 (3–11) days. There was no 30-day mortality. There was grade IIIb morbidity according to Clavien-Dindo scoring in 1 patient with postoperative bleeding that required intervention.

Tumour Relapse

There was tumour relapse diagnosed in all 8 patients. The site of the relapse was in the liver in 8 cases and in the lung in 6 cases. Peritoneum, lymph nodes, bones, and cerebral regions were all sites of lesions in 1 patient. There were multiple sites affected in 6 patients.

In cases with resectable relapse of the metastases of the liver or lung, a re-resection was performed, and this occurred in 3 and 1 patients, respectively. The time intervals from the last resection to re-resection were 12, 14, 19, and 21 months. The surgery achieved R0 status in all of these patients.

Chemotherapy

The patients received various protocols of systemic therapy, and the treatment was performed at the oncological department. Neoadjuvant therapy was performed in 6 patients with 3 to 11 cycles of various schemes (FOLFOX + bevacizumab, Xelox + bevacizumab). Adjuvant therapy after the first resection was performed in all patients (oxaliplatin + Xeloda, FOLFOX + bevacizumab, FOLFIRI, Xeloda, Xeloda + irinotecan + bevacizumab, irinotecan + aflibercept, FOLFIRINOX + bevacizumab, FOLFIRI + panitumumab). Adjuvant therapy was also performed in 6 patients after the second resection (Xeloda + bevacizumab, FOLFOX + bevacizumab (2x), XELOX + bevacizumab, capecitabine, capecitabine + oxaliplatin). After the relapse diagnosis, palliative therapy was given in 6 patients with suitable performance status.

Overall, Cancer-Specific, and Relapse-Free Survival

There was tumour relapse during the study period in all 8 of the patients, and the median relapse-free survival was 9 months (min 3, max 28 months) after the last resection of all primary diagnosed metastases.

There were six patient deaths during the study period after 17, 26, 35, 38, 42, and 44 months. The cause of death was tumour relapse in all patients. Two patients were alive, with tumour relapse 50 and 52 months after diagnosis. The median cancer-specific and overall survival was 40 months (min 17, max 52 months) (Graph 2). In 4 cases with re-resection of the metastases of the liver or lung, the median overall survival was 43 months (min 38, max 50 months) compared to 31 months (min 17, max 52 months) in the not repeatedly resectable group. The 1-year and 3-year relapse-free survival was 25% and 0%, and the overall survival was 100% and 63%, respectively.

Discussion

Published data are inconsistent for cases of simultaneous liver and lung metastases synchronous with primary colorectal cancer, and most reports present subgroup analyses of various studies with insufficient data for OS and relapse-free survival. There is currently no analysis focused only on these patients. Moreover, a definition of synchronous and simultaneous metastases varies considerably, and studies may consider as such metastases diagnosed in the time period of 0–12 months after the primary tumour or of each other, respectively [3, 4, 7, 10,11,12]. This variability can logically lead to discrepancies in patient survival. Defining a synchronous metastasis as occurring 12 months after detection of the primary tumour leads to false positive prognosis predictions and influences the treatment strategy. Therefore, we follow the suggestion presented in multidisciplinary international consensus in year 2015 [3] to managing of synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer. This work suggests that synchronous metastases from colorectal cancer should be considered only if detected at the same time or before the diagnosis of the primary tumour. Synchronous metastases, in comparison to metachronous ones, show difference in mutational pattern and clinical characteristics with inferior overall survival; thus, this definition better corresponds with the severity and prognosis of the disease [14,15,16,17].

In the case of simultaneous liver and lung metastases, analyses of the LiverMetSurvey registry [10] showed that patients who underwent resection of all metastases had similar overall survival in comparison to those who had undergone removal of isolated liver metastases. Data from 149 patients with simultaneous liver and lung metastases of colorectal cancer were analysed. The adjusted 5-year OS and RFS were similar to a group of 9185 patients with resected isolated liver metastases (5-year OS of 51.5% vs 44.5% and RFS of 31.0% vs 12.9% in liver and in liver and lung metastases group, respectively). The benefit of incomplete resection was questioned in the study of a group from MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston [18]. They demonstrated in 203 patients with simultaneous liver and lung CRC metastases, that OS was better after solely liver resection than those for the patients treated with chemotherapy only (3-year OS of 42.9% vs 14.1%). Additional lung resection was associated with further survival benefit (3-year OS 68.9% vs 42.9%). Therefore the authors concluded that the complete resection of all metastasis is the primary goal of treatment in stage IV CRC.

Encompassing altogether 74 patients, a paper published in 2015 [10] represents so far also the largest series with treatment of simultaneous liver and lung metastases synchronous with the primary tumour. The data are presented as a subgroup of aforementioned 149 patients with simultaneous liver and lung metastases. However, the authors defined synchronous metastases as those diagnosed up to 12 months after detection of the primary tumour. The synchronicity of the metastases was a significant factor affecting overall survival. Detailed analysis of the subgroup of patients with simultaneous and synchronous metastases is not presented in the paper. In the whole group with simultaneous metastases, the 5-year OS was 44.5%, and disease-free survival was 12.9%. This seems slightly superior to the results obtained in our series (3-year OS 63% and disease-free survival 0%). We assume that the metachronous metastases present at least in part of these patients have a positive influence on OS.

Another bigger group [11] analyses data of 56 patients with synchronous metastases in the liver or lung present at the time of resection of the primary tumour. There were 12 patients with simultaneous liver and lung metastases. The OS is given only for the whole group. The reported median OS was 3.5 years, which is obviously closer to our results, with an OS of 3.3 years. Similar result are presented [17] with OS of 2.8 years in 109 patients with synchronous liver metastasis after liver resection. This finding indicates that there is a larger negative prognostic importance for synchronicity of the metastases and the primary tumour with respect to OS than simultaneously detected liver and lung metastases.

Colorectal cancer diagnosed at the stage of distant spread has a 5-year OS of 4.5 to 14% and median OS of 9 months (8 to 10 months) for patients with isolate liver metastases not subjected to liver surgery [18,19,20,21]. New oncological therapy regimes combining chemotherapeutics and targeted therapy promise increased OS. A study published in 2014 [22] examined 592 patients with histologically confirmed metastatic colorectal cancer treated with FOLFIRI and cetuximab or bevacizumab. The median overall survival was 28.7 and 25.0 months, respectively. On the other hand, surgical interventions are becoming safer due to advances in operative techniques and the development of intensive care treatment. In our group of patients with multiple surgeries, we identified two severe Clavien-Dindo grade IIIb complications. Indications for resection were based on a multidisciplinary consent. If liver resection first, lung resection first, or primary tumour resection first was an individual decision based on many differing factors but dominantly on symptoms of primary tumour and/or risk of becoming not resectable by progression of metastasis. The single case of a lung first concept in our study was a patient with lung and liver metastases who needed surgical resection of lung metastases to be able to take part in a study with a neoadjuvant chemotherapy concept.

Although multiple resections were necessary to achieve R0 status, median overall survival of 40 months is a clear benefit in comparison to oncological therapy by not resected lesion. We consider median hospital stay of 9 days (3–24 days) per procedure to be appropriate for advanced disease and procedure. However, to evaluate patient’s burden and quality of life (QoL) after multiple procedures, the QoL questionnaire would be required.

The metastatic spread in multiple organs has a significant influence on survival rates. Multiple predictors of the survival rate after metastasectomy have been suggested in a number of studies [4, 7, 8, 10, 23,24,25]. Published data from 2011 [26] examined a cohort of 186 patients with liver and concomitant extrahepatic metastases and found that there were no 5-year survivors if more than one extra hepatic site was present compared with a 5-year OS of 31% in cases with single extra hepatic site metastases. Moreover, in cases of isolated concomitant lung metastases, patients showed significantly better OS than the patients with other isolated metastatic sites. Additionally, in the case of recurrence of extrahepatic disease, the patients with repeated resection showed similar OS rates to those without disease recurrence after complete resection. In our group of 4 patients with repeated resection, 3 patients died, with a median survival of 43 months in comparison to 31 months in those 4 patients where a repeated resection was not possible.

The main limitation of our study is the relatively small patient cohort and the absence of a control group. Although our results show a tendency to recurrence and prolonged OS, the analysis of a larger study group of patients would be very valuable for improving survival prediction and treatment planning.

Conclusion

Our data regarding surgical resection for simultaneous lung and liver metastases synchronous with primary colorectal cancer are well in line with other published surgical series. Patients seem to have benefit from curative resection, with tendency to prolonged overall survival. The patients fit for surgery, with possibility of R0 resection of all tumours should be offered this option and should be considered for the resection. Together with systemic therapy offers surgery further overall survival benefit. It appears to be obvious in comparison to published data of the oncological therapy. However, tumour recurrence occurred in all patients. Repeated resection was beneficial and led to further prolonged overall survival. Nevertheless, surgical intervention should be critically considered on an individual basis by the multidisciplinary tumour board.

References

Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J et al (2016) Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci Rep 6:29765. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep29765

Nordholm-Carstensen A, Krarup PM, Jorgensen LN, Wille-Jørgensen PA, Harling H, Danish Colorectal Cancer Group (2014) Danish Colorectal Cancer Group. Occurrence and survival of synchronous pulmonary metastases in colorectal cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Cancer 50:447–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2013.10.009

Adam R, de Gramont A, Figueras J, Kokudo N, Kunstlinger F, Loyer E, Poston G, Rougier P, Rubbia-Brandt L, Sobrero A, Teh C, Tejpar S, van Cutsem E, Vauthey JN, Påhlman L, of the EGOSLIM (Expert Group on OncoSurgery management of LIver Metastases) group (2015) Managing synchronous liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Cancer Treat Rev 41:729–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.06.006

Kumar R, Price TJ, Beeke C, Jain K, Patel G, Padbury R, Young GP, Roder D, Townsend A, Bishnoi S, Karapetis CS (2014) Colorectal cancer survival: an analysis of patients with metastatic disease synchronous and metachronous with the primary tumor. Clin Colorectal Cancer 13:87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2013.11.008

Kim HK, Cho JH, Lee HY, Lee J, Kim J (2014) Pulmonary metastasectomy for colorectal cancer: how many nodules, how many times? World J Gastroenterol 20:6133–6145. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i20.6133

Pfannschmidt J, Dienemann H, Hoffmann H (2007) Surgical resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published series. Ann Thorac Surg 84:324–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.02.093

Rajakannu M, Magdeleinat P, Vibert E, Ciacio O, Pittau G, Innominato P, SaCunha A, Cherqui D, Morère JF, Castaing D, Adam R (2018) Is cure possible after sequential resection of hepatic and pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer? Clin Colorectal Cancer 17:41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clcc.2017.06.006

Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH (1999) Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg 230:309–318; discussion 18-21. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004

Sourrouille I, Mordant P, Maggiori L, Dokmak S, Lesèche G, Panis Y, Belghiti J, Castier Y (2013) Long-term survival after hepatic and pulmonary resection of colorectal cancer metastases. J Surg Oncol 108:220–224. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23385

Andres A, Mentha G, Adam R, Gerstel E, Skipenko OG, Barroso E, Lopez-Ben S, Hubert C, Majno PE, Toso C (2015) Surgical management of patients with colorectal cancer and simultaneous liver and lung metastases. Br J Surg 102:691–699. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.9783

Miller G, Biernacki P, Kemeny NE, Gonen M, Downey R, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, DeMatteo RP (2007) Outcomes after resection of synchronous or metachronous hepatic and pulmonary colorectal metastases. J Am Coll Surg 205:231–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.04.039

Barlow AD, Nakas A, Pattenden C, Martin-Ucar AE, Dennison AR, Berry DP, Lloyd DM, Robertson GS, Waller DA (2009) Surgical treatment of combined hepatic and pulmonary colorectal cancer metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol 35:307–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2008.06.012

Punt CJ, Buyse M, Hohenberger P et al (2007) Endpoints in adjuvant treatment trials: a systematic review of the literature in colon cancer and proposed definitions for future trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:998–1003. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djm024

Tsai MS, Su YH, Ho MC, Liang JT, Chen TP, Lai HS, Lee PH (2007) Clinicopathological features and prognosis in resectable synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 14:786–794. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-006-9215-5

Zheng P, Ren L, Feng Q, Zhu D, Chang W, He G, Ji M, Jian M, Lin Q, Yi T, Wei Y, Xu J (2018) Differences in clinical characteristics and mutational pattern between synchronous and metachronous colorectal liver metastases. Cancer Manag Res 10:2871–2881. https://doi.org/10.2147/CMAR.S161392

Manfredi S, Lepage C, Hatem C et al (2006) Epidemiology and management of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 244:254–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000217629.94941.cf

Reding D, Pestalozzi BC, Breitenstein S, Stupp R, Clavien PA, Slankamenac K, Samaras P (2017) Treatment strategies and outcome of surgery for synchronous colorectal liver metastases. Swiss Med Wkly 147:w14486. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14486

Mise Y, Kopetz S, Mehran RJ, Aloia TA, Conrad C, Brudvik KW, Taggart MW, Vauthey JN (2015) Is complete liver resection without resection of synchronous lung metastases justified? Ann Surg Oncol 22:1585–1592. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4207-3

Noren A, Eriksson HG, Olsson LI (2016) Selection for surgery and survival of synchronous colorectal liver metastases; a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer 53:105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.055

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Ahnen DJ, Meester RGS, Barzi A, Jemal A (2017) Colorectal cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 67:7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21395

Noone AM, Howlader N, Krapcho M et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2015, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015/, based on November 2017 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2018.

Heinemann V, von Weikersthal LF, Decker T, Kiani A, Vehling-Kaiser U, al-Batran SE, Heintges T, Lerchenmüller C, Kahl C, Seipelt G, Kullmann F, Stauch M, Scheithauer W, Hielscher J, Scholz M, Müller S, Link H, Niederle N, Rost A, Höffkes HG, Moehler M, Lindig RU, Modest DP, Rossius L, Kirchner T, Jung A, Stintzing S (2014) FOLFIRI plus cetuximab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (FIRE-3): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:1065–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70330-4

Dexiang Z, Li R, Ye W, Haifu W, Yunshi Z, Qinghai Y, Shenyong Z, Bo X, Li L, Xiangou P, Haohao L, Lechi Y, Tianshu L, Jia F, Xinyu Q, Jianmin X (2012) Outcome of patients with colorectal liver metastasis: analysis of 1,613 consecutive cases. Ann Surg Oncol 19:2860–2868. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2356-9

Spelt L, Andersson B, Nilsson J, Andersson R (2012) Prognostic models for outcome following liver resection for colorectal cancer metastases: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol 38:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2011.10.013

Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, Balladur P, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Jaeck D, Association Française de Chirurgie (1996) Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie Cancer 77:1254–1262. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1254::AID-CNCR5>3.0.CO;2-I

Adam R, de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Vibert E, Salloum C, Azoulay D, Castaing D (2011) Concomitant extrahepatic disease in patients with colorectal liver metastases: when is there a place for surgery? Ann Surg 253:349–359. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318207bf2c

Acknowledgements

We hereby confirm that our research project was undergone without any financial assistance, and there are no relationships that may pose conflict of interest.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Paracelsus Medical University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The protocol for the research project has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Salzburg.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singhartinger, F.X., Varga, M., Jäger, T. et al. Outcome of Radical Surgery for Simultaneous Liver and Lung Metastases Synchronous with Primary Colorectal Cancer. Indian J Surg 84, 141–148 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-02848-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-02848-5