Abstract

Rapid advances in digital technology are revolutionizing the financial landscape. The rise of fintech has the potential to make financial systems more efficient and competitive and broaden financial inclusion. With greater technological complexity, however, fintech also poses potential systemic risks. In this paper, I use a novel dataset to trace the development of fintech (excluding cryptocurrencies) and empirically assess its impact on financial stability in a panel of 198 countries over the period 2012–2020. The analysis provides interesting insights into how fintech correlates with financial stability: (1) the impact magnitude and statistical significance of fintech depend on the type of instrument (digital lending vs. digital capital raising); (2) the overall effect of all fintech instruments together turns out to be negative because of the overwhelming share of digital lending in total, albeit statistically insignificant; and (3) while digital capital raising is estimated to have a positive effect on financial stability in advanced economies, its effect is negative in developing countries. Fintech is still small compared to traditional institutions, but rapidly expanding in riskier segments of the financial sector and creating new challenges for policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Rapid advances in digital technology are certainly revolutionizing the financial landscape, with a global surge in products and companies that employ innovative productivity-enhancing technologies to improve and automate traditional financial services. The total value of start-up investments into fintech—financial technology—worldwide increased from US$1 billion in 2008 to US$247 billion in 2022 (Fig. 1). This unabating rise of fintech is creating new opportunities and challenges in the financial services sector—from consumers to financial institutions and policymakers across the globe. It certainly has the transformative potential to make financial systems more efficient and competitive and broaden financial inclusion to the under-served populations. These prospective gains from fintech, however, are conditional on an appropriate regulatory framework. Furthermore, with greater technological complexity and exposure to cybersecurity threats, fintech also poses significant potential systemic risks to financial stability and integrity. In view of that, policymakers need to proactively assess the adequacy of regulatory frameworks for fintech to harness its benefits while mitigating risks to financial stability.

Fintech is still small compared to traditional financial institutions, but rapidly expanding, especially in riskier segments of the financial sector. There is a scarce but growing literature on fintech and its implications for financial stability, with mixed results on whether it is a threat or opportunity (Minto et al. 2017; Pantielieieva et al. 2018; Fung et al. 2020; Pieri and Timmer 2020; Vucinic 2020; Feyen et al. 2021; Daud et al. 2022; Nguyen and Dang 2022). Some of these papers conclude that fintech could mitigate financial risks by enhancing decentralization and diversification, deepening financial markets, and enhancing efficiency and transparency in the delivery of financial services. Others, however, find that that fintech could become vulnerable to cybersecurity risks, amplify market volatility, compound aggregate risk-taking and contagious behavior among both consumers and financial institutions, and thereby undermine financial stability. As shown in Fig. 2, this ambiguity in the relationship between fintech and financial stability is consistent with the findings of a broader literature on how financial innovation affects financial stability (Merton 1992; Allen and Gale 1994; Mishkin 1999; Caminal and Matutes 2002; Berger 2003; Dynan et al. 2006; Rajan 2006; Chou 2007; Claessens 2009; Gubler 2011; Henderson and Pearson 2011; Gennaioli et al. 2012; Beck et al. 2014, 2016; Laeven et al. 2015; Goetz 2018).

This paper contributes to the literature by using a novel cross-country dataset to trace the development of fintech (excluding cryptocurrencies) and conducting an analysis to empirically identify its impact on financial stability in a large panel of countries over the period 2012–2020. The analysis provides interesting insights into how fintech correlates with financial stability as gauged by the bank z-score, but also with mixed results. First, the impact magnitude and statistical significance of fintech on financial stability depend on the type of instrument (digital lending vs. digital capital raising). While digital lending as a percent of GDP has a statistically insignificant negative effect on the z-score, digital capital raising as a percent of GDP has a large and statistically significant positive effect on financial stability. Second, the impact of all fintech instruments altogether turns out to be negative because of the overwhelming share of digital lending in total, albeit statistically insignificant at conventional levels. Third, while digital capital raising is estimated to have a positive effect on financial stability in advanced economies, its effect remains negative among developing countries. These findings suggest that lending activity facilitated by fintech platforms may involve greater financial risk due to concentration and over-reliance on data-driven algorithms, while capital raising opportunities provided by fintech institutions help decentralize and diversify risk in the financial system, at least in advanced economies. It is also important to take into account that new financial technologies with complex network structures, especially on the lending front, are yet to be tested in economic downturns.

Altogether, the analysis presented in this paper finds that fintech—even at its infancy—could have significant effects on financial stability. While the magnitude and direction of this impact depends on the type of fintech instrument, the overall effect still appears to be statistically insignificant, since the average volume of fintech instruments amounts to 0.1 percent of GDP during the period 2012–2020, compared to 55 percent of GDP in domestic credit to the private sector. Looking forward, however, fast-growing and evolving fintech will have a greater effect on financial stability and consequently important policy implications, especially with increase in adaptation by large established institutions and big-tech companies. Not only do fintech firms tend to take on more risks themselves, but they also exert pressure on traditional financial institutions by degrading profitability, loosening lending standards improperly, and increasing risk-taking in operations and transactions (Cornaggia et al. 2018; FSB 2019; Baba et al. 2020; An and Rau 2021; Wang et al. 2021; Ben Naceur et al. 2023; Haddad and Hornuf 2023). Furthermore, as shown by recent developments, systemic financial risks can arise from institutions that individually are not systemically important for the financial system. Therefore, maintaining financial stability and integrity requires strong regulatory institutions, better use of technology in regulation, extensive cross-border coordination and appropriately calibrated prudential regulations for a level playing field and effective monitoring and supervision of traditional and emerging financial institutions (Arner et al. 2017; He et al. 2017; Magnuson 2018; Boot et al. 2021; Adrian et al. 2023; Bains and Wu 2023).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section II provides an overview of the data used in the empirical analysis. Section III describes the econometric methodology and presents the findings. Finally, Section IV summarizes and provides concluding remarks.

2 Data overview

The empirical analysis presented in this paper is based on a panel dataset of annual observations covering 198 countries over the period 2012–2020. The dependent variable is financial stability as measured by the country-level bank z-score, which is a widely used measure of “distance to default” (Laeven and Levine 2009; Demirguc-Kunt and Huizinga 2010; Beck et al. 2013). Most indicators of financial stability focus on the absence of systemic episodes during which the financial system fails to function, but it is also important to capture systemic resilience to stress. To this end, comparing financial buffers against risk, the bank z-score provides an explicit measure of the banking system’s solvency risk on a continuous basis. The ratio is calculated as follows:

in which \({{\text{ROA}}}_{it}\), \({{\text{CAR}}}_{it}\), and \(\sigma \left({{\text{ROA}}}_{it}\right)\) denote return on assets, the capital/asset ratio, and the standard deviation of return on assets, respectively, in country i and time t. Accordingly, the higher the value of z-score, the higher the level of financial stability.Footnote 1

The key explanatory variable of interest in this analysis is the volume of fintech transactions (excluding cryptocurrencies) as a share of GDP. The primary fintech data is obtained from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF) database that covers more than 4400 fintech entities across the world and divides fintech developments into two main categories: (1) digital lending and (2) digital capital raising (CCAF, 2021; Ran et al. 2022). Fintech refers to the use of technology to deliver financial services and products, encompassing a wide range of innovations and business models that aim to improve and automate traditional financial products and processes. In this paper, however, I use measures of alternative finance from the CCAF dataset, which consist of financial channels and instruments outside of the traditional finance system as described in detail at https://ccaf.io/. Digital lending is the volume of lending instruments through digital platforms, including balance sheet lending, peer-to-peer and marketplace lending, debt-based lending, and invoice trading. Digital capital raising refers to the volume of capital raising instruments through digital platforms, including investment-based crowdfunding such as real estate crowdfunding, and non-investment-based crowdfunding such as donation-based or reward-based crowdfunding. To have a broad measure of fintech developments, I combine digital lending and digital capital raising with other types of fintech (such as micro finance and pension-led funding) and scale it by GDP.Footnote 2

I also introduce a range of control variables, including real GDP per capita, real GDP growth, consumer price inflation, trade openness as measured by the share of exports and imports in GDP, financial development as measured by domestic credit to the private sector as a share of GDP, and government stability and bureaucratic quality as measured by composite indices constructed by the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG). These series are drawn from the World Bank’s Global Financial Development (GFD) and World Development Indicators (WDI) databases and the ICRG database.

Descriptive statistics for the variables used in the empirical analysis are provided in Table 1. There is a great degree of dispersion across countries and over time in terms of financial stability. The mean value of the bank z-score is 16.8 over the sample period, but it shows significant variation from a minimum of -0.3 to a maximum of 62.4. The main explanatory variable of interest is fintech, measured by (1) digital lending, (2) digital capital raising, and (3) total including all fintech instruments as a percent of GDP. These fintech measures exhibit substantial cross-country heterogeneity during the sample period. With an upward trend in the amount of fintech transactions, the mean value of digital lending is 0.1 percent of GDP with a minimum of nil and a maximum of 3.4 percent. Likewise, the volume of digital capital raising as a percent of GDP ranges from a minimum of nil to a maximum of 0.5 percent, with a mean value close to 0 percent over the sample period. Other explanatory variables show analogous patterns of considerable variation across countries, highlighting the importance of economic and institutional differences.

3 Empirical strategy and results

The empirical objective of this paper is to investigate the impact of fintech (excluding cryptocurrencies) on financial stability in a large panel of 198 countries over the period 2012–2020. Taking advantage of the panel structure in the data, I estimate the following baseline specification:

where \({z}_{it}\) denotes financial stability as measured by the logarithm of the z-score of the banking system in country i and time t; \({{\text{fintech}}}_{it}\) represents (1) the volume of digital lending as a percent of GDP, (2) the volume of digital capital raising as a percent of GDP, or (3) the volume of all fintech instruments as a percent of GDPFootnote 3; \({X}_{it}\) represents a vector of control variables including the logarithm of real GDP per capita, real GDP growth, inflation, trade openness, domestic credit to the private sector, and measures of government stability and bureaucratic quality. The \({\eta }_{i}\) and \({\mu }_{t}\) coefficients denote the time-invariant country-specific effects and the time effects controlling for common shocks that may affect financial stability across all countries in a given year, respectively. \({\varepsilon }_{it}\) is the idiosyncratic error term. I account for possible heteroscedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence within the data by using the Driscoll-Kraay (1998) standard errors, which are particularly robust in a panel with a shorter time dimension.

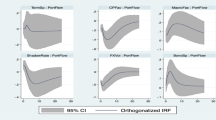

The empirical analysis provides interesting insights into how fintech endeavors affect financial stability across countries and over time. The impact magnitude and statistical significance of fintech on financial stability varies according to the type of instrument (digital lending vs. digital capital raising) when the model with control variables is estimated for the entire sample of countries. As presented in Table 2, the estimated coefficient on the volume of digital lending as a share of GDP in column [1] has a statistically insignificant negative effect on financial stability as gauged by the bank z-score, whereas the coefficient on the volume of digital capital raising as a share of GDP in column [2] is positive and statistically highly significant. In other words, an increase in digital lending is associated with a reduction the bank z-score and thereby an increase in the risk of financial instability. On the other hand, an increase in digital capital raising is associated with strengthening financial stability—with a greater magnitude compared to digital lending. The overall impact of fintech including all instruments in column [3], however, appears to be negative and statistically insignificant because of the overwhelming share of digital lending in the total amount of fintech instruments. These findings suggest that lending activity facilitated by fintech platforms may involve greater financial risk due to concentration and over-reliance on data-driven algorithms, while capital raising opportunities provided by fintech institutions help decentralize and diversify risk in the financial system.

For robustness and to obtain a better understanding of how the level of economic development influences the impact of fintech on financial stability, I estimate the model separately for different income groups—advanced economies (in Table 3) and developing countries (in Table 4).Footnote 4 This disaggregation reveals striking differences in how fintech developments affect financial stability in advanced and developing economies. First, the impact of fintech on the bank z-score becomes statistically insignificant across all specifications when the model is estimated for country subsamples, which have lower number of observations. Second, the impact of digital lending on financial stability is negative in both advanced and developing countries. Third, the impact of digital capital raising on the z-score is positive in advanced economies, but negative in developing countries. As a result, the overall effect of fintech (including all instruments) becomes positive in advanced economies but still remains in developing countries, albeit still statistically insignificant. In other words, capital raising facilitated by fintech platforms does not appear to strengthen financial stability through decentralization and diversification risks in developing countries.

With regard to control variables, I obtain consistent and intuitive estimation results. The level of real GDP per capita is inversely correlated with the bank z-score, suggesting that the level of financial stability tends to be lower in higher income countries. However, disaggregated estimations show that the coefficient on real GDP per capita is positive in advanced economies, but negative in developing countries. In other words, the relationship between income and financial stability is complex as economies develop over time. This is consistent with the stabilizing effect of real GDP growth across all countries, while inflation is found to have a significant negative impact on financial stability. Trade openness—a measure of international economic integration and development—does not appear to have statistically significant effect on the bank z-score, except in the case of advanced economies where it has a marginal positive impact. The overall level of financial development as measured by domestic credit to the private sector as a share of GDP is an important factor in determining cross-country differences in financial stability. The coefficient on financial development indicates a strong and statistically significant positive relationship with the z-score across all countries. Finally, I introduce a series of institutional and political variables, which have the expected effects on financial stability. Both measures of government stability and bureaucratic quality strengthen financial stability, with greater statistical significance in developing countries.

4 Conclusion

Rapid advances in digital technology are undoubtedly transforming the financial landscape, with a global surge in products and companies that employ innovative technologies to improve and automate traditional financial services. The total value of investments into fintech—financial technology—worldwide increased from US$1 billion in 2008 to US$247 billion in the first half of 2023. This unabating rise of fintech is creating new opportunities and challenges for the financial sector—from consumers to financial institutions and regulators. It has the transformative potential to make financial systems more efficient and competitive and broaden financial inclusion to the under-served populations. However, with greater technological complexity and exposure to cybersecurity threats, fintech also poses significant potential system-wide risks to financial stability and integrity. In this context, policymakers need to proactively assess the adequacy of regulatory frameworks for fintech to harness its benefits while mitigating risks to financial stability.

Fintech is still small compared to traditional financial institutions in many countries, but developing fast, especially in riskier business segments. There is a scarce but growing literature on fintech and its implications for financial stability, with mixed results on whether it is a threat or opportunity. On the one hand, fintech could mitigate risks to financial stability by enhancing decentralization and diversification, deepening financial markets, and enhancing efficiency and transparency in the delivery of financial services. On the other hand, fintech could become vulnerable to cybersecurity risks, amplify market volatility, increase risk-taking and contagious behavior among both consumers and financial institutions, and thereby undermine financial stability. This ambiguity in the relationship between fintech and financial stability is consistent with the findings of a broader literature on how financial innovation affects macro-financial stability.

In this paper, I use a novel cross-country dataset to trace the development of fintech (excluding cryptocurrencies) and conduct an analysis to empirically identify its impact on financial stability in a panel of 198 countries over the period 2012–2020. The analysis provides interesting insights into how fintech correlates with financial stability as gauged by the bank z-score. First, the impact magnitude and statistical significance of fintech on financial stability depends on the type of instrument (digital lending vs. digital capital raising). While digital lending as a percent of GDP has a statistically insignificant negative effect on the z-score, digital capital raising as a percent of GDP has a large and statistically significant positive effect on financial stability. Second, the impact of all fintech instruments altogether turns out to be negative because of the overwhelming share of digital lending in total, albeit statistically insignificant at conventional levels. Third, while digital capital raising is estimated to have a positive effect on financial stability in advanced economies, its effect remains negative among developing countries. These findings suggest that lending activity facilitated by fintech platforms may involve greater financial risk due to concentration and over-reliance on data-driven algorithms, while capital raising opportunities provided by fintech institutions help decentralize and diversify risk in the financial system, at least in advanced economies. It is also important to take into account that new financial technologies with complex network structures, especially on the lending front, are yet to be tested in economic downturns.

Altogether, the analysis presented in this paper finds that fintech—even at its infancy—could have significant effects on financial stability. While the magnitude and direction of this impact depends on the type of fintech instrument, the overall effect still appears to be statistically insignificant, since the average volume of fintech instruments amounts to 0.1 percent of GDP during the period 2012–2020, compared to 55 percent of GDP in domestic credit to the private sector. Looking forward, however, fast-growing fintech will have a greater effect on financial stability and consequently important policy implications, especially with increase in adaptation by large established institutions and big-tech companies.Footnote 5 Not only do fintech firms tend to take on more risks themselves, but they also exert pressure on traditional financial institutions to engage in riskier operations and transactions.

As shown by recent developments, systemic financial risks can arise from institutions that individually are not systemically important for the financial system. Maintaining financial stability and integrity requires strong regulatory institutions, better use of technology in regulation, extensive cross-border coordination and appropriately calibrated prudential regulations for a level playing field and effective monitoring and supervision of traditional and emerging financial institutions. Therefore, policymakers across the world must consider modernizing legal principles and macroprudential policies, as well as expanding the scope of existing regulations, in order to prevent a build-up of systemic risks in the financial sector by fast-growing fintech. Furthermore, given the international nature of fintech, effective supervision requires greater collaboration and coordination in developing common standards and regulatory principles.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study is obtained from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance database, the World Bank’s Global Financial Development and World Development Indicators databases, and the International Country Risk Guide database.

Notes

The bank z-score is calculated for country-years with no less than five bank-level observations and country-level aggregate figures based on bank-by-bank unconsolidated data from Bankscope and Orbis. Accordingly, it covers financial institutions with banking license, which may exclude some fintech enterprises.

The CCAF dataset excludes mobile money and internet banking, which are also operated by traditional financial institutions.

The results remain broadly unchanged when I estimate the model using the volume of digital lending or capital raising on a per capita basis.

As an additional robustness check, I estimate the model for the pre-pandemic period and obtain similar results, which are available upon request.

References

Adrian T, Moretti M, Carvalho A, Chon H, Seal K, Melo F, Surti J (2023) Good supervision: lessons from the field. IMF Working Paper No. 23/181. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Allen F, Gale D (1994) Financial innovation and risk sharing. MIT Press, Cambridge

An J, Rau R (2021) Finance, technology and disruption. Eur J Financ 27:334–345

Arner D, Zetzsche D, Buckley R, Barberis J (2017) FinTech and RegTech: enabling innovation while preserving financial stability. Georgetown J Int Affairs 18:47–58

Baba C, Batog C, Flores E, Gracia B, Karpowicz I, Kopyrski P, Roaf J, Shabunina A, van Elkan R, Xu X (2020) Fintech in Europe: promises and threats. IMF Working Paper No. 20/241. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Bains P, Wu C (2023) Institutional arrangements for Fintech regulation: supervisory monitoring. IMF Fintech Notes No. 2023/004. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Beck T, De Jonghe O, Schepens G (2013) Bank competition and stability: cross-country heterogeneity. J Financ Intermed 22:218–244

Beck T, Georgiadis G, Straub R (2014) The finance and growth nexus revisited. Econ Lett 124:382–385

Beck T, Chen T, Lin C, Song F (2016) Financial innovation: the bright and the dark sides. J Bank Finance 72:28–51

Ben Naceur S, Candelon B, Elekdag S, Emrullahu D (2023) Is FinTech eating the bank’s lunch? IMF Working Paper No. 23/239. International Monetary Fund, Washington

Berger A (2003) The economic effects of technological progress: evidence from the banking industry. J Money Credit Bank 35:141–176

Boot A, Hoffmann P, Laeven L, Ratnovski L (2021) “Fintech: what’s old, what’s new? J Financ Stabil 53:100836

Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (2021) The Global Alternative Finance Market Benchmarking Report. University of Cambridge, Cambridge

Caminal R, Matutes C (2002) Market power and banking failures. Int J Ind Organ 20:1341–1361

Chou Y (2007) Modeling financial innovation and economic growth: why the financial sector matters to the real economy. J Econ Educ 38:78–91

Claessens S (2009) Competition in the financial sector: overview of competition policies. World Bank Res Observ 24:83–118

Cornaggia J, Wolfe B, Yoo W (2018) Crowding out banks: credit substitution by peer-to-peer lending. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000593

Crisanto J, Ehrentraud J, Fabian M (2021) Big techs in finance: regulatory approaches and policy options. FSI Briefs No. 12. Bank for International Settlements, Basel

Daud S, Ahmad A, Khalid A, Azman-Saini W (2022) FinTech and financial stability: threat or opportunity? Finance Res Lett 47:102667

Demirguc-Kunt A, Huizinga H (2010) Bank activity and funding strategies: the impact on risk and returns. J Financ Econ 98:626–650

Driscoll J, Kraay A (1998) Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Stat 80:549–560

Dynan K, Elmendorf D, Sichel D (2006) Can financial innovation help to explain the reduced volatility of economic activity? J Monet Econ 53:123–150

Feyen E, Frost J, Gambacorta L, Natarajan H, Saal M (2021) Fintech and the digital transformation of financial services: implications for market structure and public policy. BIS Papers No. 117. Bank for International Settlements, Basel

Financial Stability Board (2019) BigTech in finance. Financial Stability Board, Basel

Fung D, Lee W, Yeh J, Yuen F (2020) Friend or foe: the divergent effects of FinTech on financial stability. Emerg Markets Rev 45:100727

Gennaioli N, Shleifer A, Vishny R (2012) Neglected risks, financial innovation, and financial fragility. J Financ Econ 104:452–468

Goetz M (2018) Competition and bank stability. J Financ Intermed 35:57–69

Gubler Z (2011) The financial innovation process: theory and application. Del J Corp Law 36:55–119

Haddad C, Hornuf L (2023) How do Fintech start-ups affect financial institutions’ performance and default risk? Eur J Financ 29:1761–1792

He D, Leckow R, Haksar V, Mancini-Griffoli T, Jenkinson N, Kashima M, Khiaonarong T, Rochon C, Tourpe H (2017) Fintech and financial services: initial considerations. IMF Staff Discussion Note No. 17/05. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Henderson B, Pearson N (2011) The dark side of financial innovation: a case study of the pricing of a retail financial product. J Financ Econ 100:227–247

Laeven L, Levine R (2009) Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. J Financ Econ 93:259–275

Laeven L, Levine R, Michalopoulos S (2015) Financial innovation and endogenous growth. J Financ Intermed 4:12–22

Magnuson W (2018) Regulating Fintech. Vanderbilt Law Rev 71:1167–1226

Merton R (1992) Financial innovation and economic performance. J Appl Corp Financ 24:1–24

Minto A, Voelkerling M, Wulff M (2017) Separating apples from oranges: identifying threats to financial stability originating from Fintech. Capital Markets Law J 12:428–465

Mishkin F (1999) Global financial instability: framework, events, issues. J Econ Perspect 13:3–20

Nguyen Q, Dang V (2022) The effect of FinTech development on financial stability in an emerging market: the role of market discipline. Res Global 5:100105

Pantielieieva N, Krynytsia S, Khutorna M, Potapenko L (2018) Fintech, transformation of financial intermediation and financial stability. Presented at the 2018 international scientific-practical conference problems of infocommunications

Pierri N, Timmer Y (2020) Tech in Fin before FinTech: blessing or curse for financial stability? IMF Working Paper No. 20/14. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC

Rajan R (2006) Has finance made the world riskier? Eur Financ Manag 12:499–533

Ran Z, Rau P, Ziegler T (2022) Sometimes, always, never: regulatory clarity and the development of digital financing. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3797886

Restoy (2021) Fintech regulation: how to achieve a level playing Field. FSI Occasional Paper No. 17. Bank for International Settlements, Basel

Vucinic M (2020) Potential influence of Fintech on financial stability: risks and benefits. J Cent Bank Theory Pract 9:43–66

Wang R, Liu J, Luo H (2021) Fintech development and bank risk taking in China. Eur J Financ 27:397–418

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank three anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions that led to marked improvements in the paper. An earlier version of this article benefited from comments by Parma Bains, German Villegas Bauer, Borja Gracia, Tao Sun, and Jeanne Verrier. The author is also grateful to Can Ugur for excellent research assistance. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), its Executive Board, or IMF management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cevik, S. The dark side of the moon? Fintech and financial stability. Int Rev Econ 71, 421–433 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-024-00449-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-024-00449-8