Abstract

Xylose utilization is one of the key issues in lignocellulose bioconversion. Because of glucose repression, in most engineered yeast with heterogeneous xylose metabolic pathway, xylose is not consumed until glucose is completely utilized. Although simultaneous glucose and xylose utilization have been achieved in yeast by RPE1 deletion, we regulated ZWF1 and PGI1 transcription to improve simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization by controlling the metabolic flux from glucose into the PP pathway. Xylose and glucose consumption increased by approximately 80 and 72%, respectively, whereas ZWF1 was overexpressed by multi-copy plasmids with a strong transcriptional promoter. PGI1 expression was knocked down by promoter replacement; the glucose and xylose metabolism increased when PGI1p was replaced by weak promoters, SSA1p and PDA1p. ZWF1 overexpression decreased while PGI1 down-regulation increased the ethanol yield to some extent in the recombinant strains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Xylose is the second most abundant fermentable monosaccharide released from lignocelluloses biomass [1,2,3]. Efficient xylose utilization in the lignocellulosic hydrolysate is an important issue for economic bioconversion of lignocelluloses [4,5,6,7]. To achieve high product titer, solid-to-solid pretreatments have been preferred to facilitate fermentation with high solid loading of feedstock [8,9,10]. During such pretreatments, xylan (xylose) and glucan (glucose) are usually in the same pot during fermentation [1, 11,12,13]. Simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization would be an efficient approach for lignocellulose bioconversion.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is the most widely used microorganism for industrial ethanol production, and heterogeneous xylose metabolic pathways have been engineered into S. cerevisiae [14, 15]. The following two pathways were extensively explored for xylose utilization: xylose reductase (XR) and xylitol dehydrogenase (XDH) pathway and xylose isomerase (XI) pathway [15]. For the XR-XDH pathway, previous research on co-factor balance and strain evolution significantly improved xylose utilization, although xylitol was always an unavoidable byproduct from xylose [15]. The XI pathway occurred in few eukaryotes and has been engineered and evolved to improve xylose utilization and ethanol yield [16, 17]. However, in most engineered strains, because of glucose repression, xylose is not utilized until glucose is exhausted. This leads to low fermentation efficiency [18,19,20,21].

Simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization is attracting increasing attention. Because of the limited understanding of glucose repression, it is difficult to rationally relieve glucose repression [18, 22]. Therefore, several strategies have been applied to achieve simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization [4]. Xylose-specific transporters and high-affinity transporters of xylose were developed by evolution of xylose-utilizing yeast, directed evolution or rational design of glucose transporters [23,24,25,26,27]. Except for transporter engineering, reconstitution of carbohydrate metabolic networks, such as the phosphoketolase pathway, is another approach to improve xylose utilization [15, 28]. Recently, it has been reported that disruption of some genes in glycolysis and pentose phosphate (PP) pathway resulted in simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization [5, 29]. Although simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization has been achieved in several studies, sugar consumption rate needs to be improved.

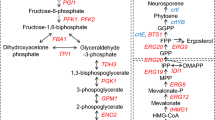

In our previous research, RPE1 deletion achieved simultaneous glucose and xylose utilization by coupling glycolysis and PP pathway in the strain SyBE_Sc17004 [5]. Xylose utilization was closely related with the metabolic flux of glucose into the PP pathway. Metabolic flux analysis revealed the proportions of glucose that entered glycolysis and PP pathway in different culture types [30]. Here we regulated key gene (ZWF1 and PGI1) expression for the metabolic flux of glucose into the PP pathway to increase xylose utilization during simultaneous xylose and glucose fermentation (Fig. 1).

Materials and Methods

Strains and Media

Yeast strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Primers used in this study are listed in Table 2.

Escherichia coli DH5α was used as a cloning host for plasmid replication and was grown in Luria–Bertani medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 5 g/L NaCl) containing 50 mg/L kanamycin at 37 °C and at 250 r/min. The yeast seed was grown in synthetic complete (SC) medium without uracil and tryptophan (SC-Ura-Trp) or SC medium without uracil, tryptophan, and leucine (SC-Ura-Trp-Leu) at 30 °C and at 200 r/min. Yeast fermentation was conducted in YP medium (10 g/L yeast extract, 20 g/L peptone) with desired concentrations of xylose and glucose.

DNA Manipulation and Plasmids Construction

Endogenous genes ZWF1 was cloned from S. cerevisiae L2612 chromosomal DNA according to its sequence information published in Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org). GO488 from Gluconobacteroxydans ATCC621, GO489 from Gluconobacteroxydans DSM3054, and H6PD from Musmusculus were synthesized artificially according to the codon-optimized sequences based on the amino acid sequences from Genebank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) (Table S1). PCR products of ZWF1, GO488, GO489, and H6PD were gel purified using a TIANgel Midi Purification Kit (TIANGEN Biotech, DP209) and digested with BsaI, and the expression cassettes LD10 andLD12 were also digested with BsaI. Then the digested gene segments and expression cassettes were ligated using T4 DNA ligase and transformed into DH5α. Selected clones were verified by colony PCR and restriction enzyme digestion. In this way, the gene expression cassettes LD10-ZWF1, LD10-GO488, LD10-GO489, LD10-H6PD, and LD12-ZWF1 were constructed. The RADOM method was applied to construct LD46-ZWF1 [31]. The fragments used for PGI1p replacement, including YEF3p, RPL8Bp, SSA1p, SSB1p, PDA1p, and the screen label kanMX were synthesized artificially.

Yeast Transformation

Yeast transformation was performed using the lithium acetate/single-stranded carrier DNA/PEG method as described previously [32, 33]. Transformants were selected on SC-Ura-Trp-Leu or SC-Ura-Trp agar plates with neomycin analogue G418 (200 μg/mL).

Yeast Fermentation

The seed cultures were grown in SC-Ura-Trp-Leu or SC-Ura-Trp medium and harvested in the late growth phase. Cells were washed twice using sterile water and inoculated into different fermentation media. The seed cells were grown in 100 mL YPXG medium (yeast extract 10 g/L, peptone 20 g/L with different concentrations of d-xylose and glucose) with an initial optimal density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0 in a 250-mL flask sealed using a rubber stopper with a needle to release CO2 produced during the fermentation process. Fermentations were performed at 30 °C and at 150 r/min. All experiments were conducted in duplicates.

Sugar and Product Analyses

The supernatant was collected for analysis on a HPLC system consisting of Waters 1515 HPLC pump, a Bio-Rad HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and Waters 2414 refractive index detector [12]. The column was eluted at 65 °C with 5 mmol/L sulfuric acid at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min.

Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis

Samples in the late exponential phase of flask cultivation were harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 4000 r/min and at 4 °C, followed by two washes with ice-cold water. Total RNA of cell samples was extracted using a Mini RNA dropout kit (Tiandz Inc., Beijing, China). Reverse transcription was performed using the Reverse Transcription kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The cDNA products were then used for the quantitative PCR reaction using the RealMaster Mix Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). Primers were designed according to sequences in the Saccharomyces Genome Database (http://www.yeastgenome.org). Quantitative RT-PCR was run in an ABI7300 Thermo cycler (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The threshold cycle value (C T) for each sample was determined using the ABI7300 software. Three biological replicates were performed for each gene. Data were normalized using ACT1 as the internal standard and analyzed according to the \( 2^{{ - \Delta \Delta C_{\text{T}} }} \) method [34].

Enzyme Assays

Cell samples in the exponential phase of flask cultivation were harvested by centrifugation for 5 min at 4000 r/min and at 4 °C. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold water and resuspended in the disintegration buffer. Crude protein was prepared by 20-min sonication at 4 °C. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford protein assay kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). The activities of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) and PGI were determined using the method described in previous studies with some modifications [35, 36]. For PGI assay, the standard assay (3 mL) contained 50 mmol/L triethanolamine hydrochloride (neutralized with KOH), 10 mmol/L MgC12 (pH 7.4), 0.4 mmol/L NADP+, 10 mmol/L fructose 6-phosphate, and 3 units of G6PDH. For G6PDH assay, the same procedures as mentioned for PGI were used except that glucose 6-phosphate was used as substrate. One unit (U) of activity of the two enzymes was defined as the amount of enzyme that produces one micromole of NADPH per minute, and the specific activity was defined as units per milligram of total protein.

Results and Discussion

Glucose 6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Overexpression to Improve Xylose and Glucose Utilization

Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase encoded by ZWF1 catalyzes the rate-limiting NADPH-producing step in the PP pathway [37]. In the strain SyBE_Sc17004, xylose metabolism was coupled with the metabolic flux of glucose into the PP pathway by RPE1 deletion [5]. G6PDH is the key enzyme to control the metabolic flux in the PP pathway from glucose. Therefore, we investigated the effect of G6PDH overexpression on xylose utilization. Several G6PDH encoding genes from different species were overexpressed, including ZWF1 from S. cerevisiae, GO488 from Gluconobacteroxydans ATCC621, GO489 from Gluconobacteroxydans DSM3054, and H6PD from Musmusculus. These G6PDH encoding genes ZWF1, GO488, GO489, and H6PD were separately expressed under the control of TPI1p promoter with a multi-copy plasmid pRS425K in the strain SyBE_Sc17004 to generate the strains SyBE_Sc122001, SyBE_Sc122002, SyBE_Sc122003, and SyBE_Sc122004, respectively. The strain SyBE_Sc122001 exhibited significant increase in simultaneous glucose and xylose utilization, while the other strains exhibited similar sugar utilization ability as the control strain (Fig. 2). The increase of glucose consumption in SyBE_Sc122001 was due to the increase of metabolic flux into the PP pathway from glucose, which drove the increase in xylose consumption due to the coupling by RPE1 deletion. Besides, ZWF1 overexpression also offered more NADPH as the co-factor for xylose reductase to accelerate xylose utilization [38, 39].

Effects of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase overexpression from different species on a glucose and b xylose utilization (The fermentation was conducted under anaerobic conditions in 100 mL YPXG medium containing 20 g/L d-xylose and 40 g/L glucose. The initial cell density was OD600 = 1.0. Data refer to the mean ± standard deviation of duplicate experiments.)

To further improve xylose utilization, we varied the promoters for ZWF1 overexpression. ZWF1 was overexpressed under the control of the promoters TDH1p and TEF1p in the strain SyBE_Sc17004 to generate SyBE_Sc122006 and SyBE_Sc122009, respectively. The engineered strains SyBE_Sc122001, SyBE_Sc122006, and SyBE_Sc122009 exhibited improved glucose and xylose utilization, but similar acceleration of sugar utilization was observed for three different promoters (Fig. 3a, b). We further quantified ZWF1 transcription using qPCR, and significantly different transcriptions for the three promoters were observed. The transcriptional strength order was TDH1p > TPI1p > TEF1p (Fig. 3c). Then the G6PDH activities were assayed in the ZWF1 overexpressed S. cerevisiae strains grown to the exponential phase by flask cultivation. Significant amplification of the G6PDH activities in vitro can be observed for the ZWF1 overexpressed strains. For the strain SyBE_Sc122006, it has been enhanced nearly 30 times compared with the control strain SyBE_Sc122000 (Fig. 3d). The inconsistence of ZWF1 transcription and translation level and sugar utilization may be because of the tight regulation of G6PDH activity. G6PDH is a component of dynamic macromolecular depot structures in S. cerevisiae. The oligomeric state of G6PDH is affected by intracellular NADPH levels; G6PDH activity is under strong feedback inhibition by NADPH [40, 41]. In addition, NADPH is a product of G6PDH. Therefore, G6PDH is a self-control enzyme. Thus, the G6PDH activity in vivo and the gene expression strength are not necessarily in positive correlation [42]. Therefore, the observation in this study is reasonable: when we overexpressed ZWF1, G6PDH activity was improved in varying degrees compared with the control and led to increased sugar utilization. However, when ZWF1 expression was further enhanced, G6PDH activity was inhibited, and no further increased sugar utilization was observed, although ZWF1 transcriptional and translational levels were much higher. Ethanol and xylitol accumulation of these ZWF1 overexpressed strains are shown in Fig. S1. The ethanol yields of ZWF1 overexpressed strains are shown in Table 3. In SyBE_Sc122009, ethanol yield reached 0.423 g/g(sugar) and this was the optimal yield among the ZWF1 overexpressed strains. In other strains the ethanol yields were slightly lower than those in the control strain SyBE_Sc122000. These results were consistent with a previous research that has shown that increasing the G6PDH activity resulted in lower ethanol yield [43]. Thus ZWF1 overexpression did improve the sugar consumption rate and simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization, but lowered ethanol yield.

Effect of ZWF1 overexpression on the engineered strains. a Glucose, b xylose, c ZWF1 relative expression in different strains, and d G6PDH activity in different strains (The fermentation was conducted under anaerobic conditions in 100 mL YPXG medium containing 20 g/L d-xylose and 80 g/L glucose. Significance levels of Student’s t test: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.)

Effect of PGI1 Down-Regulationon Xylose and Glucose Utilization

As mentioned above, glucose 6-phosphate is the key node for the metabolic flux into the glycolysis and PP pathways. Thus, we hypothesized that the down-regulation of PGI1, encoding phosphoglucose isomerase, would be helpful to increase the metabolic flux into the PP pathway from glucose. However, phosphoglucose isomerase–deficient (pgi1) strains of S. cerevisiae exhibited growth defect on glucose [44]. Here, to knockdown PGI1 expression, we designed the replacement of PGI1 promoter in SyBE_Sc17004 with several weak promoters, including YEF3p, RPL8Bp, SSB1p, SSA1p, and PDA1p. In this order, the strains SyBE_Sc122037, SyBE_Sc122038, SyBE_Sc122039, SyBE_Sc122040, and SyBE_Sc122041 were obtained. Promoter replacements were confirmed by a diagnostic PCR. As shown in Fig. 4, the knockdown by YEF3p, RPL8Bp, and SSB1p resulted in the decrease of glucose and xylose utilization. However, the knockdown by SSA1p and PDA1p led to a slight increase of glucose and xylose utilization. The knockdown of PGI1 in all the strains was verified using qPCR and the transcriptional strengths were in the following order: PGI1p > YEF3p > RPL8Bp > SSB1p > SSA1p > PDA1p (Fig. 4c), which is consistent with data derived from GFP intensity [45]. At the same time, PGI activities were also assayed in these recombinant S. cerevisiae strains grown to the exponential phase in flask fermentation (Fig. 4d). Ethanol and xylitol accumulation were detected during cultivation of these recombinant strains (Fig. S2). The ethanol yields of these recombinant strains are listed in Table 4. All of the PGI1 down-regulation strains showed higher ethanol yields than the control strain SyBE_Sc17004. These results indicated that glucose and xylose utilization can increase lightly when PGI1 is knocked down significantly. This was consistent with the conclusion of a previous research that down-regulation of PGI1 alone synergistically assisted xylitol production [36]. When the glycolysis pathway was blocked by pgi deletion in E. coli, xylose and glucose were consumed in the ratio of 1:1 at a relative slow rate [29]. In pgi1 mutant S. cerevisiae, some extra cofactor transforming genes, such as GDH2 coding for NAD(+)-specific glutamate dehydrogenase or gapB encoding NADPH-utilizing glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, are essential for the growth on glucose [44]. But these strains often did not tolerate glucose very well. So, further improvements to these yeast strains for glucose and xylose co-fermentation are needed, such as up-regulation of the non-oxidative PP pathway flux and improvement of xylose metabolic capacity.

Effect of Sugar Concentration on Xylose and Glucose Utilization

In S. cerevisiae there are no specific xylose transporters, and xylose enters the cell through native hexose transporters. Transporter engineering for xylose significantly improved xylose utilization by increasing the affinity of the transporter for xylose [5]. If the transporter is the limiting step for xylose utilization in present biosystems, sugar concentration and the ratio of xylose and glucose would influence xylose utilization significantly. We designed several fermentation experiments with different sugar concentrations, and the strains SyBE_Sc122009 and SyBE_Sc122000 were used as examples. As shown in Fig. 5, the ratio of co-consumed xylose/glucose was almost stable for each strain at different sugar concentrations and ratios. Compared with SyBE_Sc122000, both xylose consumption and glucose metabolism were enhanced in SyBE_Sc122009 under all the conditions. Previous research has revealed that the increase in the concentrations of glucose decreased xylose consumption and that hexose transporter overexpression Hxt7 partially relieved the inhibitory effects of increasing glucose concentration [46]. Ishola et al. [47, 48] reported that glucose concentration affected xylose uptake in SSFF or in reverse membrane bioreactors. In recombinant flocculent S. cerevisiae the best ratio of glucose/xylose for the highest xylose consumption rate was 2:3 among different ratios [49]. But our results showed that the ratio of co-consumed xylose/glucose was independent on sugar ratio and concentration both in the chassis strain SyBE_Sc17004 [5] and in the ZWF1 overexpressed strain SyBE_Sc122009. Hence, we inferred that sugar transporters may not be the limiting factor for xylose utilization in our strains. On the other hand, these results were just the consequence of the coupling of glycolysis and PP pathway by RPE1 deletion, as the PP pathway is the major source of NADPH that is necessary in S.cerevisiae [50]. The PP pathway network needs xylulose 5-phosphate as substrate and in our strains xylose is the only source of it. Thus, it is the metabolism request that drives the xylose utilization.

Effect of glucose concentration on sugar utilization. The fermentation was conducted under anaerobic conditions in 100 mL YPXG medium containing 10 g/L d-xylose and a 10 g/L glucose, b 20 g/L glucose and c 40 g/L glucose, and d the ratio of simultaneously consumed xylose/glucose in different concentrations of glucose

Conclusions

We developed several approaches to increase simultaneous xylose and glucose utilization in the xylose-utilizing S. cerevisiae with the deletion of RPE1. We made the following conclusions according to our results: (1) ZWF1 overexpression can increase glucose and xylose utilization, but G6PDH is under tight regulation when ZWF1 transcription is too high; (2) down-regulation of PGI1 is not efficient to increase xylose utilization; (3) ZWF1 overexpression decreased the ethanol yield while PGI1 down-regulation can increase it slightly; (4) the ratio of simultaneously consumed xylose/glucose is independent on the concentration and ratio of xylose and glucose in the medium.

Abbreviations

- GO488 :

-

Glucose6-phosphate dehydrogenase of GluconobacteroxydansATCC621

- GO489 :

-

Glucose6-phosphate dehydrogenase of GluconobacteroxydansDSM3054

- H6PD :

-

Hexose6-phosphate dehydrogenase of Musmusculus

- KLSB lab:

-

Key Laboratory of Systems Bioengineering (Ministry of Education of China), School of Chemical Engineering and Technology, Tianjin University

- XYL1 :

-

Xylose reductase

- XYL2 :

-

Xylitol dehydrogenase

- XKS :

-

Xylulokinase

- RPE :

-

Ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase

- RKI :

-

Ribose-5-phosphate ketol-isomerase

- TAL :

-

Transaldolase

- TKL :

-

Transketolase

- ZWF1 :

-

Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- SOL :

-

6-Phosphogluconolactonase

- GND :

-

6-Phosphaogluconate dehydrogenase

- PGI1 :

-

Phosphoglucoseisomerase

- Ga-3-P:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

- G-6-P:

-

Glucose 6-phosphate

- DHAP:

-

Dihydroxyacetone phosphate

- S-7-P:

-

Sedoheptulose 7-phosphate

- F-6-P:

-

Fructose 6-phosphate

- F-1,6-BP:

-

1,6 Fructose diphosphate

- E-4-P:

-

Erythrose 4-phosphate

- Gl-6-P:

-

Glucono-1,5-lactone 6-phosphate

- Gn-6-P:

-

Gluconate 6-phosphate

- Ru-5-P:

-

Ribulose 5-phosphate

- Ri-5-P:

-

Ribose 5-phosphate

- X-5-P:

-

Xylulose 5-phosphate

References

Li BZ, Balan V, Yuan YJ et al (2010) Process optimization to convert forage and sweet sorghum bagasse to ethanol based on ammonia fiber expansion (AFEX) pretreatment. Bioresour Technol 101(4):1285–1292

Qin L, Liu ZH, Jin MJ et al (2013) High temperature aqueous ammonia pretreatment and post-washing enhance the high solids enzymatic hydrolysis of corn stover. Bioresour Technol 146:504–511

Liu ZH, Qin L, Jin MJ et al (2013) Evaluation of storage methods for the conversion of corn stover biomass to sugars based on steam explosion pretreatment. Bioresour Technol 132:5–15

Zhang GC, Liu JJ, Kong II et al (2015) Combining C6 and C5 sugar metabolism for enhancing microbial bioconversion. Curr Opin Chem Biol 29:49–57

Shen MH, Song H, Li BZ et al (2015) Deletion of d-ribulose-5-phosphate 3-epimerase (RPE1) induces simultaneous utilization of xylose and glucose in xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Lett 37(5):1031–1036

Zha J, Hu ML, Shen MH et al (2012) Balance of XYL1 and XYL2 expression in different yeast chassis for improved xylose fermentation. Front Microbiol 3:355

Zha J, Li BZ, Shen MH et al (2013) Optimization of CDT-1 and XYL1 expression for balanced co-production of ethanol and xylitol from cellobiose and xylose by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 8(7):e68317

Jin M, Gunawan C, Balan V et al (2012) Consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) of AFEX™-pretreated corn stover for ethanol production using Clostridium phytofermentans at a high solids loading. Biotechnol Bioeng 109(8):1929–1936

Zhang J, Hou WL, Bao J (2015) Reactors for high solid loading pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 152:1–16

Qin L, Li WC, Zhu JQ et al (2015) Ethylenediamine pretreatment changes cellulose allomorph and lignin structure of lignocellulose at ambient pressure. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:174

Zhu JQ, Qin L, Li BZ et al (2014) Simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation of aqueous ammonia pretreated corn stover with an engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae SyBE005. Bioresour Technol 169:9–18

Zhu JQ, Qin L, Li WC et al (2015) Simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation of dry diluted acid pretreated corn stover at high dry matter loading: overcoming the inhibitors by non-tolerant yeast. Bioresour Technol 198:39–46

Liu ZH, Chen HZ (2016) Simultaneous saccharification and co-fermentation for improving the xylose utilization of steam exploded corn stover at high solid loading. Bioresour Technol 201:15–26

Cam Y, Alkim C, Trichez D et al (2016) Engineering of a synthetic metabolic pathway for the assimilation of (d)-xylose into value-added chemicals. ACS Synth Biol 5(7):607–618

Kim SR, Park YC, Jin YS et al (2013) Strain engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for enhanced xylose metabolism. Biotechnol Adv 31(6):851–861

Qi X, Zha J, Liu GG et al (2015) Heterologous xylose isomerase pathway and evolutionary engineering improve xylose utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Front Microbiol 6:1165

Lee SM, Jellison T, Alper HS (2012) Directed evolution of xylose isomerase for improved xylose catabolism and fermentation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol 78(16):5708–5716

Kim JH, Block DE, Mills DA (2010) Simultaneous consumption of pentose and hexose sugars: an optimal microbial phenotype for efficient fermentation of lignocellulosic biomass. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 88(5):1077–1085

Zaldivar J, Nielsen J, Olsson L (2001) Fuel ethanol production from lignocellulose: a challenge for metabolic engineering and process integration. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56(1/2):17–34

Kötter P, Ciriacy M (1993) Xylose fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 38(6):776–783

Hahn-Hagerdal B, Karhumaa K, Fonseca C et al (2007) Towards industrial pentose-fermenting yeast strains. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 74(5):937–953

Gancedo JM (1998) Yeast carbon catabolite repression. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62(2):334–361

Wang M, Yu CZ, Zhao HM (2016) Identification of an important motif that controls the activity and specificity of sugar transporters. Biotechnol Bioeng 113(7):1460–1467

Shin HY, Nijland JG, de Waal PP et al (2015) An engineered cryptic Hxt11 sugar transporter facilitates glucose-xylose co-consumption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:176

Farwick A, Bruder S, Schadeweg V et al (2014) Engineering of yeast hexose transporters to transport d-xylose without inhibition by d-glucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(14):5159–5164

Young EM, Tong A, Bui H et al (2014) Rewiring yeast sugar transporter preference through modifying a conserved protein motif. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(1):131–136

Nijland JG, Shin HY, de Jong RM et al (2014) Engineering of an endogenous hexose transporter into a specific d-xylose transporter facilitates glucose-xylose co-consumption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels 7:168

Liu L, Zhang L, Tang W et al (2012) Phosphoketolase pathway for xylose catabolism in Clostridium acetobutylicum revealed by C-13 metabolic flux analysis. J Bacteriol 194(19):5413–5422

Gawand P, Hyland P, Ekins A et al (2013) Novel approach to engineer strains for simultaneous sugar utilization. Metab Eng 20:63–72

Gombert AK, dos Santos MM, Christensen B et al (2001) Network identification and flux quantification in the central metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae under different conditions of glucose repression. J Bacteriol 183(4):1441–1451

Lin QH, Jia B, Mitchell LA et al (2014) RADOM, an efficient in vivo method for assembling designed DNA fragments up to 10 kb long in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. ACS Synth Biol 4(3):213–220

Wang X, Bai X, Chen DF et al (2015) Increasing proline and myo-inositol improves tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to the mixture of multiple lignocellulose-derived inhibitors. Biotechnol Biofuels 8:142

Gietz RD, Schiestl RH, Willems AR et al (1995) Studies on the transformation of intact yeast cells by the LiAc/SS-DNA/PEG procedure. Yeast 11(4):355–360

Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ (2008) Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3(6):1101–1108

Maitra PK, Lobo Z (1971) A kinetic study of glycolytic enzyme synthesis in yeast. J Biol Chem 246(2):475–488

Oh YJ, Lee TH, Lee SH et al (2007) Dual modulation of glucose 6-phosphate metabolism to increase NADPH-dependent xylitol production in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Catal B Enzym 47(1/2):37–42

Nogae I, Johnston M (1990) Isolation and characterization of the ZWF1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Gene 96(2):161–169

Jo JH, Oh SY, Lee HS et al (2015) Dual utilization of NADPH and NADH cofactors enhances xylitol production in engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol J 10(12):1935–1943

Zha J, Shen MH, Hu ML et al (2014) Enhanced expression of genes involved in initial xylose metabolism and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway in the improved xylose-utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae through evolutionary engineering. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 41(1):27–39

Saliola M, Tramonti A, Lanini C et al (2012) Intracellular NADPH levels affect the oligomeric state of the glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Eukaryot Cell 11(12):1503–1511

Tramonti A, Saliola M (2015) Glucose 6-phosphate and alcohol dehydrogenase activities are components of dynamic macromolecular depots structures. Biochim Biophys Acta 1850(6):1120–1130

Au SWN, Naylor CE, Gover S et al (1999) Solution of the structure of tetrameric human glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase by molecular replacement. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 55:826–834

Jeppsson M, Johansson B, Jensen PR et al (2003) The level of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity strongly influences xylose fermentation and inhibitor sensitivity in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. Yeast 20(15):1263–1272

Toivari MH, Maaheimo H, Penttilä M et al (2010) Enhancing the flux of d-glucose to the pentose phosphate pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of d-ribose and ribitol. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 85(3):731–739

Peng BY, Williams TC, Henry M et al (2015) Controlling heterologous gene expression in yeast cell factories on different carbon substrates and across the diauxic shift: a comparison of yeast promoter activities. Microb Cell Fact 14:91

Subtil T, Boles E (2012) Competition between pentoses and glucose during uptake and catabolism in recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Biofuels 5:14

Ishola MM, Brandberg T, Taherzadeh MJ (2015) Simultaneous glucose and xylose utilization for improved ethanol production from lignocellulosic biomass through SSFF with encapsulated yeast. Biomass Bioenerg 77:192–199

Ishola MM, Ylitervo P, Taherzadeh MJ (2015) Co-utilization of glucose and xylose for enhanced lignocellulosic ethanol production with reverse membrane bioreactors. Membranes 5(4):844–856

Matsushika A, Sawayama S (2013) Characterization of a recombinant flocculent Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain that co-ferments glucose and xylose: I. Influence of the ratio of glucose/xylose on ethanol production. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 169(3):712–721

Jamieson DJ (1998) Oxidative stress responses of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14(16):1511–1527

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (“973” Program, No. 2013CB733601), the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (“863” Program, No. 2012AA02A701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21390203), and the Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Committee (No. 13RCGFSY19800).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Li, B., Li, C. et al. Enhancement of Simultaneous Xylose and Glucose Utilization by Regulating ZWF1 and PGI1 in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae . Trans. Tianjin Univ. 23, 201–210 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12209-017-0048-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12209-017-0048-z