Abstract

The attraction and retention of volunteers are vital components to the operation of a nonprofit organization (NPO). Understanding the motivations of volunteers is an important step to recruiting and retaining them. To add to our understanding of volunteer motivation, this research seeks to contribute to the nonprofit literature by applying an updated version of Vroom’s (1964) expectancy theory of motivation to volunteerism to determine whether individuals who regularly volunteer and who volunteer in groups feel less powerlessness and have more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and toward helping others. Analysis of 210 surveyed consumers in a metropolitan area of approximately one million people in the midwestern U.S. found that individuals that volunteer on a regular, ongoing basis have significantly more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and toward helping others in general. The results also indicated that individuals that volunteered as part of a group held more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations. Implications of these findings, limitations of the study, and directions for future research are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Given their limited resources and desire to do more with less, nonprofit organizations (NPOs) rely on volunteers who share their goals and values to help execute their missions. While overall volunteer hours and fundraising totals have hit record highs in recent years, research by the University of Maryland’s Do Good Institute has also indicated that the percentage of Americans who volunteer and donate to nonprofits is at its lowest in twenty years (Ahmad 2018). These results were culled by an analysis of data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics and included in a report titled “Where are America’s Volunteers?” Even more concerning is their finding that volunteerism’s decline is “surprisingly more prevalent in states historically rich in social capital” (p. 1). The group norms provided by social networks would be thought to generally buck the decline of volunteerism trend; however, this is currently not the case.

Reliance on a smaller number of volunteers is not likely to be a winning strategy for the long-term. Additionally, over one-third of volunteers don’t return to any nonprofit due to poor management and lack of recognition, adding up to an estimated $38 billion worth of labor (Eisner et al. 2009). Among the management failings cited were not matching volunteers’ skills with appropriate assignments, not recognizing the contributions of volunteers, not measuring the impact of volunteers, not providing volunteers with training, and not training paid staff to work with volunteers. Given their limited promotion budgets to attract new volunteers, keeping the ones they have is vital for nonprofits. Retention of volunteers has likely become more difficult and an even higher priority for all NPOs, since Covid-19 has negatively impacted nearly all charitable organizations, according to a survey conducted by Charities Aid Foundation of America (The Nonprofit Times 2020).

All of the above, taken together, underscores the importance of finding and maintaining a regular group of committed volunteers. To better recruit and retain volunteers, we must have a thorough understanding of their motivations. To add to this understanding, this research seeks to contribute to the nonprofit literature by applying Vroom’s (1964) well-known expectancy theory of motivation to volunteerism to determine whether individuals who regularly volunteer and who volunteer in groups feel less powerlessness and have more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and toward helping others. This study represents a novel application of expectancy theory and has also adopted subsequent researchers’ suggestions regarding its application. First of these is that, per Van Eerde and Thierry (1996), the components of expectancy theory have been adopted, but not the multiplicative model. Also, this study acknowledges the often intrinsic nature of valence and rewards in volunteerism (Galbraith and Cummings 1967; Porter and Lawler 1968). Finally, in comparing those who volunteer alone and in groups, this study examines the social component of expectancy theory suggested by Lloyd and Mertens (2018).

2 Background

2.1 Volunteerism

The Cambridge Dictionary (2020) defines volunteerism as “the practice of doing work for good causes, without being paid for it.” Wymer Jr. et al. (1996) discuss the generally agreed upon opinion that altruistic motivations (e.g. to help those less fortunate) and egoistic motivations (e.g. enjoyment or to develop skills to help their career) are not necessarily mutually exclusive, and that most individuals who volunteer because of a genuine desire to help others still want to have a rewarding experience. In a systematic review of thirty-three studies on volunteerism motives, Dunn et al. (2016) found that common motives were helping others and socializing. Diversity in friendships and more education have been found to increase the likelihood of volunteering, while greater intensity of religious belief increases level of volunteerism (Forbes and Zampelli 2014). These authors also found that both likelihood to volunteer and level of volunteerism were increased for those with more informal social networking, formal group involvement, and greater religious participation. Nichols and Ralston (2012) found that individuals felt status and identity-based benefits as a result of their volunteer activities. Other-oriented motives are positively associated with satisfaction and intention to continue volunteering, while self-oriented motives were negatively associated with the same (Stukas et al. 2016). In their study of “Super-Volunteers” (defined as individuals who volunteer 10+ hours per week), Einolf and Yung (2018) found that shared values was the most important factor in choosing a volunteer opportunity.

Volunteerism has been studied along demographic and psychographic lines. Briggs et al. (2007) found that even if teens think highly of an organization, the nature of the volunteer task is the key to participation and quality of their work. Young people also feel that volunteer activities are beneficial only if they’re chosen freely (Warburton and Smith 2003). Additionally, while age has been found to be negatively related among older consumers, materialism, physical health, and subjective well-being are all positively related to volunteerism (Wei et al. 2012). This study also found the volunteerism rate to be lowest among individuals 65-years old and higher. The practice of volunteering has been found to be associated with both greater life satisfaction and better physical health for individuals who volunteer, when compared to those who do not (Van Willigen 2000). Older volunteers were found to experience greater increases in satisfaction and health than younger volunteers. Wymer Jr. (2003) examined segmentation of volunteers and found the sub-segment of literacy volunteers to be different from other volunteers along demographic, social-lifestyle, personality, and value domains, with the exception of empathy and self-esteem from the personality domain. Dolnicar and Randle (2007) also created a typology of volunteer types based on a positioning analysis. Their segments were labelled altruists, leisure volunteers, political volunteers, and church volunteers.

Of the many contexts that have served as a backdrop for the study of volunteerism are Ajzen’s (1988) Theory of Planned Behavior in which behavior is preceded by intentions, which is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. For instance, Brayley et al. (2015) found that motives for volunteering were, in order of strength, subjective norms, attitude, understanding, and perceived behavioral control. Another is the functional approach to volunteering which posits that individuals will volunteer if one or more of six motivational functions (altruistic value expression, understanding, career, social, protective and esteem) are perceived to be fulfilled (Clary et al. 1992). Greenslade and White’s (2005) study supported both of these approaches. In their qualitative study of online volunteering, Silva et al. (2018) found that altruistic motivations, learning, and career rewards are the most common motivations for volunteerism in that medium. This study applies another well-respected theory in motivation, Vroom’s Expectancy Theory (Vroom 1964), to volunteerism. Expectancy theory is similar to these other mentioned theories in that they all account for attitudes (e.g., values in the functional approach) and a social component as prescribed for expectancy theory by Lloyd and Mertens (2018) (e.g., subjective norms in the theory of planned behavior). However, one area in which expectancy theory differs is in its inclusion of the instrumentality factor that takes motivation a step further. That is the belief that performance will lead to the desired outcome. In this study, this is represented by the attitude toward the nonprofit in the belief that volunteerism efforts will be translated by the NPO into the ultimate goal of helping others.

2.2 Expectancy theory

Vroom’s Expectancy Theory of Motivation (Vroom 1964) posits that the individual evaluates choices and makes decisions based on the choice that is believed will lead to the most desirable personal outcome to optimize pleasure and minimize pain. As a cognitive theory of motivation, expectancy theory focuses on subjectively rational human behavior and is based on three core concepts: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence that combine to create motivational force (MF). The initial motive for creating expectancy theory was to explain motivation, and specifically the voluntary choice made by an individual when options were available. It was geared toward work roles and focused on choices made, satisfaction with roles, and level of performance in the chosen work role.

The three core concepts of expectancy theory warrant additional discussion. Expectancy has been referred to as an effort-performance relation (Harris et al. 2017; Lunenburg 2011), or the perceived likelihood that you can successfully execute and attempted behavior (Baumann and Bonner 2017). Expectancy is the subjective belief of the probability of an outcome occurring based on the effort an individual puts forth. It is a cognitive evaluation that is influenced by the individual’s own experiences and personal attributes. Vroom asserted that individual choices and external events influence specific outcomes (Vroom 1964). Instrumentality represents the influence of a given behavior on an outcome (Baumann and Bonner 2017) and essentially posits that if you perform well, the anticipated outcome will occur. Finally, Vroom defined valence as an affective orientation toward a specific outcome; put differently, it is the perceived value an individual links to a specific outcome or reward at a given point in time minus the assumed costs associated with taking a given set of actions. A positive valence exists when the individual prefers achieving the result versus not achieving it. Examples of positive valances may include compensation, desired work, job promotions, etc. (Baciu 2017). A zero valence indicates indifference to attaining an outcome or not. A negative valence exists when the individual would prefer to not achieve the outcome as it doesn’t fulfill a need or personal goal, or if a potential negative consequence such as disciplinary action or termination outstripped the positive gain from the reward (Baciu 2017).

According to expectancy theory, to be motivated and individual must believe that a certain level of effort leads to performance (expectancy), that performance leads to particular rewards (instrumentality), and the rewards received outweigh the costs associated with the effort (valence) (Purvis et al. 2015). Vroom defined motivational force as the product of the three cores factors. Being a multiplicative model, if any one of the factors were zero, so would motivation. Further, if valence were negative, the motivation would be to avoid the reward. The theory has been the basis of extensive research, though concern has been identified with the mathematical equation (Lawler and Suttle 1973), with Vroom (1995) sharing that more focus was placed on the equation than what he had intended. As more of an inspirational, rather than literal framework for this research, we have not adopted the mathematical formula of the expectancy theory. Further, Van Eerde and Thierry (1996) conducted a meta-analysis evaluating seventy-seven studies on expectancy theory. They found that different studies interpreted the model differently and techniques were not all accurately applied. Their suggestion was to use the individual components of the model instead of the model itself. We have followed this suggestion for this study.

Subsequent expectancy theory work in the literature focused on variables related to work motivation (Sayeed 1985), occupational choice (Brooks and Betz 1990), pre-employment test performance (Sanchez et al. 2000), sales coaching (Pousa and Mathieu 2010), and entrepreneurship (Renko et al. 2012). Specific industries examined include construction (Ghoddousi et al. 2014) and healthcare (Bilkovski and Delis 2004). The testing and the applicability of the theory over the past fifty years has expended to other areas including project management (Purvis et al. 2015), networking (Porter and Woo 2015), academic settings (Geiger and Cooper 1996; Fagbohungbe 2012), energy efficient home refurbishment (Baumhof et al. 2017), blogging (Liao et al. 2011), pro-environmental behavior (Kiatkawsin and Han 2017), and intentions to implement social media to support knowledge exchange (Behringer and Sassenberg 2015).

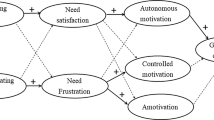

Vroom asserted that the strength or aversion of a desire was based on extrinsic factors. However, as House (1971) pointed out, Galbraith and Cummings (1967) extended expectancy theory by including that valences associated with a specific behavior can be intrinsic to the behavior itself. Porter and Lawler (1968) likewise theorized that individual motivation included both intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. With this extension included, expectancy theory lends itself nicely to studies within the nonprofit sector. Volunteers make choices and decisions as to which nonprofit to support, how often, and in what ways to support them based on an assessment of the ultimate reward, which they asses to deem as desirable or non-desirable. Consistent with the above literature, and most relevant to this study, volunteerism is often rewarded intrinsically rather than extrinsically. This study examines differences between regular and sporadic volunteers in terms of their levels of powerlessness, their attitudes toward charitable organizations, and their attitudes toward helping others. Consistent with the addition of the social component to expectancy theory (Lloyd and Mertens 2018), this study also examines across the same variables those who voluntary solo versus in groups. As represented in fig. 1, these volunteerism attitudes reflect the three primary factors of expectancy theory: expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

3 Hypotheses

3.1 Attitudes

Seeman (1959) conceptualized powerlessness as one of five parts of alienation, along normlessness, meaninglessness, social isolation, and self-estrangement. Specifically, Seeman defines powerlessness as “the expectance or probability held by the individual that his own behavior cannot determine the occurrence of outcomes or reinforcements, he seeks” (p. 784). According to Krishnan (2008, p. 22), “This socio-psychological view of powerlessness as an expectancy makes it closely related to Rotter’s (1966) notion of external control of reinforcements. According to Rotter, an individual’s belief in the external locus of control of reinforcements demonstrates one’s expectancy that outcomes of situations are determined by forces external to one’s self- such as by powerful others, chance, or fate.” So, if expectancy is the belief that one’s efforts will result in the attainment of desired performance, this powerlessness factor seems to capture the opposite of this value of effort. In this case the effort is volunteering for nonprofits. Those who volunteer often would likely believe that their actions have the power to make a difference by providing one input (effort) into the work needed by NPOs. Hence, we propose:

-

H1a:

Individuals who volunteer on an ongoing, regular basis are lower in powerlessness.

Webb et al. (2000, p. 300) define attitudes toward charitable organizations as “global and relatively enduring evaluations with regard to the nonprofit organizations (NPOs) that help individuals.” Among the factors most frequently cited as having an impact on attitudes toward charitable organizations are familiarity (Bendapudi et al. 1996; Schlegelmilch 1988), and perceived efficiency and effectiveness (Bendapudi et al. 1996; Harvey 1990; Schlegelmilch et al. 1992). Instrumentality refers to the belief that the reward will be received if the performance expectation is met. This attitude reflects the belief that volunteerism with nonprofits, as the intermediary for charitable efforts (Bendapudi et al. 1996), will result in the goal of helping people. People who volunteer on a regular basis likely believe, not only that their actions can make a difference, but also that the input they provide to NPOs is then converted by the charitable organization(s) into the goal of helping others. Hence:

-

H1b:

Individuals who volunteer on an ongoing, regular basis have more positive attitudes toward nonprofit organizations.

Webb, et al. (2000, p. 300) define attitudes toward helping others as “global and relatively enduring evaluations with regard to helping or assisting other people.” Research consensus cites personal norms (Piliavin and Charng 1990; Schwartz 1970; Schwartz and Howard 1982) and internalized values (Schwartz and Howard 1984) as the sources of helping behavior. Meanwhile, research has suggested that both empathic (Batson 1987) and egoistic (Cialdini et al. 1981) motives for helping behavior exist. Research has specifically found that individual’s attitudes are positively related to donation behavior (Burnkrant and Page Jr. 1982; LaTour and Manrai 1989; Mclntyre et al. 1986). If valence refers to the value placed on the rewards of the outcome (helping others), an individual’s attitude toward helping others serves as proxy of this value. That is, regardless of their motivation, people who regularly volunteer value helping others.

-

H1c:

Individuals who volunteer on an ongoing, regular basis have more positive attitudes toward helping others.

3.2 Group volunteerism

Lloyd and Mertens (2018) proposed inclusion of social context as an additional element of expectancy theory. They contend that expectancy, instrumentality, and valence are influenced by social factors within an organization as well as across sectors; that an individual worker’s motivational force is influenced by relationships with other workers. These social factors can have a positive or negative effect on the worker. Nesbit (2013) found that individuals are more likely to volunteer if their family members do and that volunteerism often requires a catalyst and that often happens in the home. Further, Garver et al. (2009) found that students volunteer for certain organizations when they know current volunteers or that organization, Dunn et al. (2016) found that socializing was noted as among the common motives for volunteerism. Brayley et al. (2015) found that subjective norms were the strongest predictor of willingness to volunteer. All of these findings seem to corroborate the impact that social influence can have on individuals’ volunteerism behavior. Regardless of motive, we contend that volunteering in a group, through social influence, can impact the attitudes of the volunteer in the following ways:

-

H2a:

Individuals who volunteer with groups are lower in powerlessness.

-

H2b:

Individuals who volunteer with groups have more positive attitudes toward nonprofit organizations.

-

H2c:

Individuals who volunteer with groups have more positive attitudes toward helping others.

4 Method

4.1 Sample

Study respondents were recruited via email from a list purchased from a mailing list broker of individuals residing in a midwestern U.S. metropolitan area with a population of approximately 1 million. Not including undeliverable emails, the overall systematic random sample included 10,142 consumers in the metropolitan area. From these, 220 responded for a response rate of 2.2%. After removing cases for missing items, the resulting sample consisted of 210 responses. The sample was 53% female, with 55% of respondents falling within the ages of 50–69. The sample was 73% Caucasian, 10% African-American, 7% Native American, 2% Asian-American, 1% Hispanic, and 7% was divided among other ethnicities. The sample was quite diverse in terms of both education and income levels. While 23% indicated a high school education and/or some college, 11% indicated an associate degree, 36% indicated a four-year college degree and/or some graduate work, and 26% reported having completed a graduate degree. Income was below $60,000 for 36% of respondents, 34% reported within the $60,000 to $120,000 range, and 21% reported income over $120,000. The sample reported a wide range of occupations.

4.2 Measures

The study constructs were all measured using reliable, established scales or subsets thereof found in the marketing/sociology literature. The scales employed were all multi-item, and responses were recorded via a 5-point Likert-type format with endpoints of strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Powerlessness was measured using a four-item subscale of Neal and Rettig’s (1967) scale to measure alienation (of which powerlessness is a subset). An example item is “It is only wishful thinking to believe that one can really influence what happens in society at large.” The scale exhibited acceptable reliability (α = .71). Attitude Toward Charitable Organizations (4-item subset) and Attitude Toward Helping Others (2-item subset) were measured via scales established by Webb et al. (2000). An example attitude toward charitable organizations item, that touches on the effectiveness of NPOs is “Charitable organizations have been quite successful in helping the needy.” An example attitude toward helping others item is “People should be more charitable towards others in society.” The reliability for these scales was also found to be acceptable (α = .80 and α = .70, respectively). The descriptive statistics and correlations among these variables can be examined in Table 1. Volunteerism was measured using the following item: “On what occasions have you volunteered?” The first response option was “on an ongoing, regular basis,” continuing through “special events,” and “sporadically.” This resulted in a dichotomous variable in that the first response equaled an active volunteer, which the subsequent responses did not and were hence combined into one category of lower level of volunteerism. Respondents were also asked if they volunteered alone, with formal groups, or with informal groups of family and/or friends.

4.3 Results

Mean comparisons were executed in SPSS 26 to test our hypotheses. Via t-test, the means of the volunteerism variables were compared across whether respondents were regular volunteers or not. Hypothesis 1 predicted that individuals who volunteer on an ongoing, regular basis are a) lower in powerlessness, and have more positive attitudes toward b) nonprofit organizations, and c) helping others. With significant mean differences of .283 (p = .016) and .218 (p = .029), the data provided support for hypotheses 1b and 1c, respectively. That is, individuals who volunteer on a regular, ongoing basis report more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and helping others than those who do not. While the means differed as hypothesized, the difference in powerlessness from those who volunteered regularly and those who did not (−.146) was not significantly large. So, hypothesis 1a was not supported. These results can be examined in Table 2.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that individuals who volunteer with groups are a) lower in powerlessness and have more positive attitudes toward b) nonprofit organizations, and c) helping others. With a significant mean difference of .385 (p = .002), the data provided support for hypothesis 2b. That is, individuals who volunteer in groups report more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations than those who volunteer solo. While the means differed as hypothesized, the difference in attitude toward helping others from those who volunteered in groups and those who volunteered solo (.130) was not significantly large. So, hypothesis 2c was not supported. Finally, powerlessness was also not significantly different for those who volunteered in groups versus alone. So, hypothesis 2a was not supported. These results can also be examined in Table 2.

A post hoc one-way ANOVA was run to further explore these attitudes across a wider range of options. Specifically, we compared means across groups that volunteered either a) solo, b) as part of a formal group, c) as part of an informal group (family/friends), or d) some combination of these. These results proved to be quite interesting. First, the overall ANOVA test of the null hypothesis of equality of all means was conducted to control the inflation of family-wise error rate. The overall null hypothesis of equal means was rejected for attitude toward both charitable organizations and helping others (see Table 3 for further details), so multiple comparisons could then be examined using the Duncan procedure. In both cases, the most positive attitudes were held by those who volunteer as part of a formal group. Further, these means, along with those for individuals who indicated a combination of options, were significantly greater than attitude values for those who volunteered alone or with an informal group. These values can be examined in Table 4.

5 Discussion and implications

This research examined volunteerism from an expectancy theory perspective. Specifically, we compared the attitudes of powerlessness (representing expectancy), attitude toward charitable organizations (representing instrumentality), and attitude toward helping others (representing valence) across individuals based on how often they volunteer and whether they volunteer in groups or by themselves. This study represents a novel application of expectancy theory, exhibited by its adoption of the components but not the multiplicative model (Van Eerde and Thierry 1996), the intrinsic nature of valence and rewards in volunteerism (Galbraith and Cummings 1967; Porter and Lawler 1968), and (by comparing solo and group volunteerism) the social component of expectancy theory (Lloyd and Mertens 2018).

The data indicate that individuals that volunteer on a regular, ongoing basis have significantly more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and toward helping others in general. These findings suggest that in our expectancy model of volunteerism, instrumentality and valence are more influential than is expectancy for motivating individuals to volunteer. The link between regular volunteerism and positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and helping others are likely recursive relationships. Individuals who value helping others and the organizations that do so, are more likely to volunteer. Further, the experience of volunteering likely increases the positivity of their attitudes toward NPOs and helping others. This could happen through various means. For example, the experience of volunteering and thereby helping others could be rewarding extrinsically and, more likely, intrinsically for the volunteer. They would then want to continue volunteering, regardless of whether their motivation was altruistic or egoistic. Meanwhile, it could be that the experience of volunteering is also quite eye-opening in that they are able to see the considerable need of the NPOs firsthand, considering the razor thin budgets and staff with which many of these organizations function. Realizing that the need is indeed more dire than they might have initially perceived, the volunteering experience helps increasingly motivate the individual to do their part to help others through their chosen NPO(s). Relatedly, given some of the reasons for volunteer defection, the volunteer experience is also an opportunity for NPOs to properly train volunteers, match them with appropriate work for their skills and interests, and recognize their contributions. All of these examples of proper management of volunteers (and more) can result in increasingly positive attitudes toward the organization among volunteers, which can lead to more consistent volunteerism among current volunteers and also help recruit new ones as needed.

The results also indicated that individuals that volunteered as part of a group held more positive attitudes toward charitable organizations. So, where group volunteerism is concerned, instrumentality is central to motivation to volunteer. This is logical since the group in which one may volunteer may be the NPO itself. These results underscore the power of social influence in groups. Further post hoc analyses indicated that the most positive attitudes toward charitable organizations and helping others were held by those individuals whom volunteered with a formal group, when compared to those who volunteered by themselves or with an informal group of friends and family. Among the implications here for charitable organizations, is the benefit of partnering with organizations in their promotion and volunteer events. Many organizations have been doing this for years, whether they have joined forces with churches, civic organizations, or even fraternity and sorority organizations at universities. The additional social influence provided by these partner groups can go a long way in increasing participation in volunteerism within their ranks of members. Since many studies have also found that many individuals do volunteer for social reasons in addition to doing good, the relationships within the group can also improve retention of volunteers.

6 Limitations and future research directions

As with all research efforts, there are some notable limitations of this study. One such limitation is the self-report, cross-sectional nature of our survey. Biases such as social desirability can arise with self-report measures and a longitudinal study would be desirable for this research in order to determine how volunteerism attitudes evolve over time. A second limitation is the low response rate of our sample. There is a chance that nonresponse bias exists in our data. Perhaps only those interested in nonprofit volunteerism participated in the study. However, since we measured the degree to which individuals were involved in volunteerism and those that weren’t interested weren’t of interest to the study, this bias would seem to have very little if any impact on our research. Finally, this study is limited to the constructs included in our model. There are myriad of potential areas of study that can impact volunteerism.

Among the areas ripe for a deeper investigation are the social influence on volunteerism within groups, both formal and informal, building on Dolnicar and Randle’s (2007) market segmentation of the international volunteering market. For instance, are religious or political organizations more interested in volunteerism and do they differ in terms of motivation? Also of interest would be further examination into the retention of volunteers, given their churn rate (Eisner et al. 2009). Finally, the study on online volunteerism by Silva et al. (2018) brings a multitude of directions for further study. Especially, given the impact of Covid-19 on society, the study of alternative methods of volunteerism is certainly warranted going forward.

Data Availability

Data is available upon request.

References

Ahmad, K. (2018). Fewer Americans are volunteering and giving than any time in the last two decades. https://phys.org/news/2018-11-americans-volunteering-decades.html. Accessed 10 June 2020.

Ajzen, I. (1988). Attitudes, personality, and behavior. Chicago: Dorsey.

Baciu, L. E. (2017). Expectancy theory explaining civil servants’ work motivation: Evidence from a Romanian city hall. USV Annals of Economics and Public Administration, 17(2(26)), 146-160.

Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 65–122). New York: Academic Press.

Baumann, M., & Bonner, B. (2017). An expectancy theory approach to group coordination: Expertise, task features, and member behavior. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 30(2), 407–419.

Baumhof, R., Decker, T., Röder, H., & Menrad, K. (2017). An expectancy theory approach: What motivates and differentiates German house owners in the context of energy efficient refurbishment measures? Energy & Buildings, 152, 483–491.

Behringer, N., & Sassenberg, K. (2015). Introducing social media for knowledge management: Determinants of employees’ intentions to adopt new tools. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 290–296.

Bendapudi, N., Singh, S. N., & Bendapudi, V. (1996). Enhancing helping behavior: An integrative framework for promotion planning. Journal of Marketing, 60(3), 33–49.

Bilkovski, R. N., & Delis, S. (2004). Work force motivation, a novel application of expectancy theory in emergency medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 44(4), S130.

Brayley, N., Obst, P. L., White, K. M., Lewis, I. M., Warburton, J., & Spencer, N. M. (2015). Examining the predictive value of combining the theory of planned behaviour and the volunteer functions inventory. Australian Journal of Psychology, 67(3), 149–156.

Briggs, E., Landry, T., & Wood, C. (2007). Beyond just being there: An examination of the impact of attitudes, materialism, and self-esteem on the quality of helping behavior in youth volunteers. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 18(2), 27–45.

Brooks, L., & Betz, N. (1990). Utility of expectancy theory in predicting occupational choices in college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37(1), 57–64.

Burnkrant, R., & Page Jr., T. (1982). An examination of the convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity of Fishbein's behavioral intention model. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 550–561.

Cambridge Dictionary. (2020). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/volunteerism. Accessed 5 June 2020.

Cialdini, R. B., Baumann, D. J., & Kenrick, D. T. (1981). Insights from sadness: A three-step model of the development of altruism as hedonism. Developmental Review, 1(3), 207–223.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Ridge, R. D. (1992). A functional strategy for the recruitment, placement and retention of volunteers. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 2, 333–350.

Dolnicar, S., & Randle, M. (2007). The international volunteering market: Market segments and competitive relations. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12(4), 350–370.

Dunn, J., Chambers, S., & Hyde, M. (2016). Systematic review of motives for episodic volunteering. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 27(1), 425–464.

Einolf, C. J., & Yung, C. (2018). Super-volunteers: Who are they and how do we get one? Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47(4), 789–812.

Eisner, D., Grimm, R. T., Jr., Maynard, S. & Washburn, S. (2009). The new volunteer workforce. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter, 32–37.

Fagbohungbe, B. O. (2012). Students’ performance in core and service courses: A test of valence-instrumentality expectancy theory. Journal of Management and Sustainability, 2(2), 236–240.

Forbes, K. F., & Zampelli, E. M. (2014). Volunteerism: The influences of social, religious, and human capital. Nonprofit & Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(2), 227–253.

Galbraith, J. R., & Cummings, L. L. (1967). An empirical investigation of the motivational determinants of task performance: Interactive effects between instrumentality-valence and motivation-ability. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 2, 237–257.

Garver, M. S., Divine, R. L., & Spralls, S. A. (2009). Segmentation analysis of the volunteering preferences of university students. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(1), 1–23.

Geiger, M., & Cooper, E. (1996). Using expectancy theory to assess student motivation. Issues in Accounting Education, 11(1), 113.

Ghoddousi, P., Bahrami, N., Chileshe, N., & Hosseini, M. R. (2014). Mapping site-based construction workers’ motivation: Expectancy theory approach. Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, 14(1), 60–77.

Greenslade, J. H., & White, K. M. (2005). The prediction of above-average participation in volunteerism: A test of the theory of planned behavior and the volunteers functions inventory in older Australian adults. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(2), 155–172.

Harris, K., Murphy, K., Dipietro, R., & Line, N. (2017). The antecedents and outcomes of food safety motivators for restaurant workers: An expectancy framework. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 63, 53–62.

Harvey, J. W. (1990). Benefit segmentation for fund raisers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18(1), 77–86.

House, R. (1971). A path goal theory of leader effectiveness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 16(3), 321–339.

Kiatkawsin, K., & Han, H. (2017). Young travelers' intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tourism Management, 59, 76–88.

Krishnan, P. (2008). Consumer alienation by brands: Examining the roles of powerlessness and relationship types (thesis). Winnipeg: University of Manitoba.

LaTour, S. A., & Manrai, A. K. (1989). Interactive impact of informational and normative influence on donations. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(3), 327–335.

Lawler, E. E., & Suttle, J. L. (1973). Expectancy theory and job behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 9(3), 482–503.

Liao, H., Liu, S., & Pi, S. (2011). Modeling motivations for blogging: An expectancy theory analysis. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 39(2), 251–264.

Lloyd, R., & Mertens, D. (2018). Expecting more out of expectancy theory: History urges inclusion of the social context. International Management Review, 14(1), 24–37.

Lunenburg, F. C. (2011). Expectancy theory of motivation: Motivating by altering expectations. International Journal of Management, Business, and Administration, 15, 1.

Mclntyre, P., Bamett, M. A., Harris, R. J., Shanteau, J., Skowronski, J., & Klassen, M. (1986). Psychological factors influencing decisions to donate organs. In M. Wallendorf and P. Anderson (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research (pp. 331-334), 14, Provo, UT: Combined proceedings Association for Consumer Research.

Neal, A. G., & Rettig, S. (1967). On the multidimensionality of alienation. American Sociological Review, 32(1), 54–64.

Nesbit, R. (2013). The influence of family and household members on individual volunteer choices. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 42(6), 1134–1154.

Nichols, G., & Ralston, R. (2012). The rewards of individual engagement in volunteering: A missing dimension of the big society. Environment & Planning A: Economy and Space, 44(12), 2974–2987.

Piliavin, J. A., & Charng, H. (1990). Altruism: A review of recent theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 16, 27–65.

Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. E. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Homewood: Irwin-Dorsey Press.

Porter, C., & Woo, S. (2015). Untangling the networking phenomenon: A dynamic psychological perspective on how and why people network. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1477–1500.

Pousa, C., & Mathieu, A. (2010). Sales managers’ motivation to coach salespeople: An exploration using expectancy theory. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 8(1), 34–50.

Purvis, R. L., Zagenczyk, T. J., & McCray, G. E. (2015). What's in it for me? Using expectancy theory and climate to explain stakeholder participation, its direction and intensity. International Journal of Project Management, 33(1), 3–14.

Renko, M., Kroeck, K., & Bullough, A. (2012). Expectancy theory and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(3), 667–684.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal vs. external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–28.

Sanchez, R., Truxillo, D., & Bauer, T. (2000). Development and examination of an expectancy-based measure of test-taking motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 739–750.

Sayeed, O. (1985). Work motivation and employee performance: A review of VIE theory. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 21(2), 147–172.

Schlegelmilch, B. B. (1988). Targeting of fund-raising appeals: How to identify donors. European Journal of Marketing, 22(1), 31–40.

Schlegelmilch, B. B., Diamantopoulos, A., & Love, A. (1992). Determinants of charity giving: An interdisciplinary review of the literature and suggestions for future research. In C. T. Allen et al. (Eds.), Marketing theory and applications (pp. 507–516). Chicago: Combined Proceedings, American Marketing Association.

Schwartz, S. H. (1970). Elicitation of moral obligation and self-sacrificing behavior: An experimental study of volunteering to be a bone marrow donor. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(4), 283–293.

Schwartz, S. H., & Howard, J. (1982). Helping and cooperation: A self-based motivational model. In V. J. Derlega & J. Grzelak (Eds.), Cooperation and helping behavior: Theories and research (pp. 327–353). New York: Academic Press.

Schwartz, S. H., & Howard, J. (1984). Internalized values as motivators of altruism. In E. Staub, D. Bar-Tal, J. Karylowski, & J. Reykowski (Eds.), Development and maintenance of Prosocial behavior: International perspectives on positive morality (pp. 229–256). New York: Plenum.

Seeman, M. (1959). On the meaning of AliQUdXion. American Sociological Review, 24(6), 58–91.

Silva, F., Proenca, T., & Ferreira, M. R. (2018). Volunteers’ perspective on online volunteering- a qualitative approach. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 15(4), 531–552.

Stukas, A., Hoye, R., Nicholson, M., Brown, K., & Aisbett, L. (2016). Motivations to volunteer and their associations with volunteers’ well-being. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 112–132.

The Nonprofit Times (2020). Covid-19 negatively impacting nearly all charities. https://www.thenonprofittimes.com/donors/covid-19-negatively-impacting-nearly-all-charities/. Accessed 10 June 2020.

Van Eerde, W., & Thierry, H. (1996). Vroom's expectancy models and work-related criteria: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 575–586.

Van Willigen, M. (2000). Differential benefits of volunteering across the life course. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55B(5), S308–S318.

Vroom, V. H. (1964). Work and motivation. New York: Wiley.

Vroom, V. H. (1995). Work and motivation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Warburton, J., & Smith, J. (2003). Out of the generosity of your heart: Are we creating active citizens through compulsory volunteer programmes for young people in Australia? Social Policy & Administration, 37(7), 772–786.

Webb, D. J., Green, C. L., & Brashear, T. G. (2000). Development and validation of scales to measure attitudes influencing monetary donations to charitable organizations. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 299–309.

Wei, Y., Donthu, N., & Bernhardt, K. (2012). Volunteerism of older adults in the United States. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 9(1), 1–18.

Wymer Jr., W. W. (2003). Differentiating literacy volunteers: A segmentation analysis for target marketing. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 8(3), 267–285.

Wymer Jr., W. W., Riecken, G., & Yavas, U. (1996). Determinants of volunteerism: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 4(1), 3–26.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zboja, J.J., Jackson, R.W. & Grimes-Rose, M. An expectancy theory perspective of volunteerism: the roles of powerlessness, attitude toward charitable organizations, and attitude toward helping others. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 17, 493–507 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00260-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-020-00260-5