Abstract

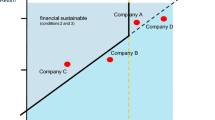

This paper empirically investigates the performance of portfolio screening strategies based on ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) scores, by testing three main hypotheses motivated by the introduction of sustainability considerations within portfolio theory: i) ESG screened portfolios overperform the benchmark in the long term only if the exclusion threshold is low; ii) ESG screened portfolios do not overperform the benchmark in the short term independently of the exclusion threshold; iii) ESG screened portfolios overperform the benchmark in terms of systemic risk in periods of financial distress. To this end, negative and positive screening strategies based on Bloomberg ESG disclosure scores and different screening thresholds are set up from the 559 stocks belonging to the EURO STOXX index in the period 2007–2021. The risk-adjusted performance of the ESG screened portfolios is compared with the benchmark-passive one based on Sharpe Ratio (SR) and alphas (from both a one-factor model and the Carhart four-factor model) so as to test performance over total and systemic risk respectively. Two main results emerge. First, we prove overperformance of screened portfolios only in the long run and in the presence of negative screening strategies with a low screening threshold. Second, we do not find clear evidence of over-compensation for systemic risk in all periods of financial distress, thus the alleged safe-haven property of ESG portfolios is not always there. Given the increasing attention for sustainability, our results have relevant implications for both individual investors and the asset management industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available as they contain proprietary information that the authors acquired through a license. Information on how to obtain them and reproduce the analysis is available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

For an excellent review of the early literature on SRI see Renneboog et al. (2008).

Overall, in 2020 total assets committed to sustainable and responsible investment strategies reached $17 trillion in the US (95% increase from 2016) and $12 trillion in EU substantially stable, mainly because of stricter sustainability standards introduced in the EU (Technical Expert Group 2020). Sustainable assets can be equity-type (e.g. stocks with high ESG rating/score) or debt-type (e.g. green bonds, social bonds). Green bonds have been mostly investigated for the existence of a green premium and its determinants (Zerbib 2019; Fatica et al. 2021), whereas the literature on social bonds is still scant and Torricelli and Pellati (2023) is the first study on the social premium.

In this connection, the European debt crisis (2010–2011) had a major effect in Greece, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, but not all over the EU.

Unlike Pástor et al. (2021), we do not assume that shocks in the demand for sustainable assets average to zero over the long term, at least not in the period we consider (2007–2021) characterized by a significant growth in sustainable investments following initiatives promoted by both the United Nations and new requirements by Regulatory authorities. Therefore, until a new normal, in which ESG shocks average to zero, we cannot see a complete reconciliation between the realized long term overperformance of sustainable assets and their expected underperformance according to financial theory.

This is also consistent with an agency perspective, executives are opportunist agents, who tend to make decisions that are consistent with their self-interest, hence a long-term perspective is able to align executives’ interests with those of society (Jensen and Meckling 1976).

According to Van Duuren et al. (2016) SRI has several similarities with active management since most ESG investors also aim to beat the benchmark.

The mean–variance approach can be reconciled with the expected utility theory by assuming investors with a quadratic utility function (for any return distribution) and/or normally distributed returns (for any expected utility function).

The relationship between ESG portfolio returns and its systemic risk is not necessarily straightforward, in fact Varmaz et al. (2022) discuss that in the literature there are two competing approaches about ESG dimension: ESG affecting portfolio returns by means of systemic risk and ESG bringing portfolio additional returns without changing the covariance structure among the assets. They also propose a test to identify the approach explaining stock returns in a specific investment universe, but the latter goes beyond the scope of the present study.

While the literature lacks a universal definition of an asset's safe-haven properties, most studies associate the “safe-haven” label with risk, often referring to assets that exhibit negative (or no) correlation with other assets during extreme market conditions (Baur and Lucey 2010). However, this paper takes a different perspective by focusing on portfolio returns and adopting a risk-adjusted performance viewpoint, as supported by more recent research (e.g. Singh 2020; Lins et al. 2017).

The EURO STOXX is a broad and liquid subset of the STOXX Europe 600 and represents large, mid and small capitalization companies of 11 Eurozone countries: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain.

Sustainalytics, for example, has a low coverage before 2014 because before 2014, it was driven by the needs of Sustainalytics clients (Auer 2016).

The objective of the paper is to compare strategies which do not require the achievement of a minimum ESG score, but rather selecting stocks according to their ESG scores in a comparative manner. Hence, by screening on the distribution of ESG scores, we can accommodate potential variations and trends over time such as the ESG market becoming more mature.

Each year we consider only stocks belonging to the EURO STOXX in January of that year and only those with an ESG score in order to precisely sort them. The latter condition implies that in the first years of the period analysed a smaller number of stocks is included in each portfolio since from 2007 to 2021 Bloomberg gradually increased the number of stocks covered by an ESG score.

Moreover, the equally weighting approach is very common in actively managed mutual funds (Block and French 2002).

Equally weighted portfolios have equal weights (1/N) in period t = 1 when portfolios are set up, then stocks weights might change due to price movements and active management decisions. Hence transaction costs may arise because of portfolio rebalancing towards target equal weights and screening decisions. According to DeMiguel et al. (2009) portfolio turnover over month t + 1 is calculated as one-half times the sum of the absolute value of the trades across the N assets:

$$\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j=1}^{N}|{\widehat{w}}_{j,t+1}-{\widehat{w}}_{j,{t}^{+}}|$$where \({\widehat{w}}_{j,t+1}\) is the percentage target weight of stock j at time t + 1 in the portfolio after rebalancing and \({\widehat{w}}_{j,{t}^{+}}\)is the percentage weight of stock j at time t + 1 in the portfolio before rebalancing. Then we average over time in order to get an indicator of average turnover for a portfolio.

References

Ainsworth A, Corbett A, Satchell S (2018) Psychic dividends of socially responsible investment portfolios. J Asset Manag 19(3):179–190

Alessandrini F, Jondeau E (2020) ESG investing: From sin stocks to smart beta. J Portfolio Manage 46(3):75–94

Auer B (2016) Do Socially Responsible Investment Policies Add or Destroy European Stock Portfolio Value? J Bus Ethics 135(2):381–397

Baker M, Bergstresser D, Serafeim G, Wurgler J (2018) Financing the response to climate change: The pricing and ownership of US green bonds. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Papers N. 25194, pp 1−42

Bauer R, Derwall J, Otten R (2007) The ethical mutual fund performance debate: New evidence from Canada. J Bus Ethics 70(2):111–124

Baur DG, Lucey BM (2010) Is gold a hedge or a safe haven? An analysis of stocks, bonds and gold. Financ Rev 45(2):217–229

Beal DJ, Goyen M, Philips P (2005) Why do we invest ethically? J Investing 14(3):66–78

Bénabou R, Tirole J (2010) Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica 77(305):1–19

Benson KL, Humphrey JE (2008) Socially responsible investment funds: Investor reaction to current and past returns. J Bank Finance 32(9):1850–1859

Block SB, French DW (2002) The effect of portfolio weighting on investment performance evaluation: the case of actively managed mutual funds. J Econ Finance 26(1):16–30

Bollen NP (2007) Mutual fund attributes and investor behavior. J Financ Quant Anal 42(3):683–708

Bolton P, Kacperczyk M (2021) Do investors care about carbon risk? J Financ Econ 142(2):517–549

Bolton P, Kacperczyk M (2023) Firm commitments. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Papers N. 31244, pp 1–66

Broadstock DC, Chan K, Cheng LT, Wang X (2020) The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ Res Lett 38:101716

Capelle-Blancard G, Monjon S (2014) The performance of socially responsible funds: Does the screening process matter? Eur Financ Manag 20(3):494–520

Carhart MM (1997) On persistence in mutual fund performance. J Financ 52(1):57–82

Demers E, Hendrikse J, Joos P, Lev B (2021) ESG did not immunize stocks during the COVID-19 crisis, but investments in intangible assets did. J Bus Financ Acc 48(3–4):433–462

DeMiguel V, Garlappi L, Uppal R (2009) Optimal versus naive diversification: How inefficient is the 1/N portfolio strategy? Rev Financ Stud 22(5):1915–1953

Derwall J, Koedijk K (2009) Socially responsible fixed-income funds. J Bus Financ Acc 36(1–2):210–229

Edmans A (2011) Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. J Financ Econ 101(3):621–640

European Commission (2018) Action plan: financing sustainable growth, COM/2018/097 final. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52018DC0097&from=EN. Accessed Apr 2022

Fama EF, French KR (1993) Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J Financ Econ 33(1):3–56

Fatica S, Panzica R, Rancan M (2021) The pricing of green bonds: Are financial institutions special? J Financ Stab 54:100873

Galema R, Plantinga A, Scholtens B (2008) The stocks at stake: Return and risk in socially responsible investment. J Bank Finance 32(12):2646–2654

Girard EC, Rahman H, Stone BA (2007) Socially responsible investments: Goody-two-shoes or bad to the bone? J Investing 16(1):96–110

Glode V (2011) Why mutual funds “underperform.” J Financ Econ 99(3):546–559

Glück M, Hübel B, Scholz H (2020) Currency Conversion of Fama-French Factors: How and Why. J Portfolio Manage 47(2):157–175

GSIA (2021) 2020 global sustainable investment review. http://www.gsi-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/GSIR-20201.pdf. Accessed Mar 2022

Gutsche G, Ziegler A (2019) Which private investors are willing to pay for sustainable investments? Empirical evidence from stated choice experiments. J Bank Finance 102(C):193–214

Hartzmark SM, Sussman AB (2019) Do investors value sustainability? A natural experiment examining ranking and fund flows. J Financ 74(6):2789–2837

Herremans IM, Akathaporn P, McInnes M (1993) An investigation of corporate social responsibility reputation and economic performance. Acc Organ Soc 18(7–8):587–604

Hübel B, Scholz H (2020) Integrating sustainability risks in asset management: the role of ESG exposures and ESG ratings. J Asset Manag 21(1):52–69

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360

Kempf A, Osthoff P (2007) The effect of socially responsible investing on portfolio performance. Eur Financ Manag 13(5):908–922

Lins KV, Servaes H, Tamayo A (2017) Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J Financ 72(4):1785–1824

Nagy Z, Giese G (2020) MSCI ESG indexes during the coronavirus crisis. https://www.msci.com/www/blog-posts/msci-esg-indexes-during-the/01781235361. Accessed Mar 2022

Ortas E, Moneva JM, Salvador M (2014) Do social and environmental screens influence ethical portfolio performance? Evidence from Europe. BRQ Bus Res Q 17(1):11–21

Pástor L, Stambaugh RF, Taylor LA (2021) Sustainable investing in equilibrium. J Financ Econ 142(2):550–571

Pástor L, Stambaugh RF, Taylor LA (2023) Green Tilts. National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Papers N. 31320, pp 1–76

Pástor L, Vorsatz MB (2020) Mutual fund performance and flows during the COVID-19 crisis. Rev Asset Pricing Studies 10(4):791–833

Pedini L, Severini S (2022) Exploring the hedge, diversifier and safe haven properties of ESG investments: A cross-quantilogram analysis. Munich Personal RePEc Archive, MPRA Paper N. 112339, pp 1–24

Principles for Responsible Investment (2017) The SDG investment case. https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=5909. Accessed Apr 2022

Renneboog L, Horst J, Zhang C (2008) Socially responsible investments: Institutional aspects, performance and investor behaviour. J Bank Finance 32(9):1723–1742

Revelli C, Viviani JL (2015) Financial performance of socially responsible investing (SRI): what have we learned? A meta-analysis. Business Ethics: Eur Rev 24(2):158–185

Rossi MC, Sansone D, van Soest A, Torricelli C (2019) Household preferences for Socially Responsible Investments. J Bank Finance 105(C):107–120

Rubbaniy G, Khalid AA, Rizwan MF, Ali S (2022) Are ESG stocks safe-haven during COVID-19? Stud Econ Financ 39(2):239–255

Sharpe WF (1994) The Sharpe Ratio. J Portfolio Management 21(1):49–58

Singh A (2020) COVID-19 and safer investment bets. Finance Research Letters 36(C):101729

Takahashi H, Yamada K (2021) When the Japanese stock market meets COVID-19: Impact of ownership, China and US exposure, and ESG channels. Int Rev Financ Anal 74:101670

Technical Expert Group (TEG) (2020) Taxonomy: Final report of the Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/business_economy_euro/banking_and_finance/documents/200309-sustainable-finance-teg-final-report-taxonomy_en.pdf

Torricelli C, Pellati E (2023) Social Bonds and the “Social Premium.” J Econ Finance 47(3):600–619

Van Duuren E, Plantinga A, Scholtens B (2016) ESG integration and the investment management process: Fundamental investing reinvented. J Bus Ethics 138(3):525–533

Varmaz A, Fieberg C, Poddig T (2022) Portfolio optimization for sustainable investments. Available at SSRN 3859616, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3859616. Accessed Sept 2022

Verheyden T, Eccles RG, Feiner A (2016) ESG for all? The impact of ESG screening on return, risk, and diversification. J Appl Corp Financ 28(2):47–55

Willis A (2020) ESG as an equity vaccine. Morningstar Market Insights. https://www.morningstar.ca/ca/news/201741/esg-as-an-equity-vaccine.aspx. Accessed Mar 2022

Zerbib OD (2019) The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. J Bank Finance 98(C):39–60

Acknowledgements

Authors wish to thank for helpful comments and suggestions: the Editor and two anonymous referees, participants to the 24th International Conference on Computational Statistics (Bologna, 2022) and participants to the 4th Corporate Governance & Risk Management in Financial Institutions International Conference (Rome, 2023).

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Financial interests

The authors declare they have no financial interests.

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bertelli, B., Torricelli, C. The trade-off between ESG screening and portfolio diversification in the short and in the long run. J Econ Finan (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-023-09652-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-023-09652-9

Keywords

- Sustainable finance

- Socially Responsible Investments (SRI)

- Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG)

- Positive and negative screening strategies

- Portfolio performance measures