Abstract

The Great Recession was the worst economic downturn in the U.S. since the Great Depression of the 1930s. This research focusses on children in five income-quintile groups before, during, and following the Great Recession by analyzing changing disparities across these groups using a new Index of Parental Employment Insecurity, nine additional well-being indicators, and the overall Child Well-Being Index. The new Index of Parental Employment Insecurity captures employment insecurity more fully than the official U.S. monthly unemployment rate by using a comprehensive approach spanning 15-month periods (combining January-to-December measures for a calendar year with measures for March of the following year), based not only on two traditional unemployment indicators, but also two indicators of “hidden unemployment” and two indicators of “underemployment”. The other nine well-being indicators, also with children or youth as the unit of analysis, are median family income, health insurance coverage, Prekindergarten enrollment, three health indicators – very good or excellent health, obesity, and activity limitations – two indicators reflecting family experience – one-parent families and residential mobility – and idle or disconnected youth. For each of the 10 indicators in 1994, children in the lowest-income, lower-middle-income, and middle-income families had lower levels of well-being, often much lower, than children in the highest-income families. These had gaps narrowed, as of 2014, for all three of the lowest-income groups by about two-thirds for health insurance coverage and by about two-fifths for Prekindergarten enrollment. Compared to the highest-income group, however, the gaps had widened for the middle-income group for most indicators, the direction of changes in gaps was mixed for the lower-middle-income group, and the gaps had narrowed, usually by about one-fourth, for the lowest-income group, leaving gaps for the lowest-income group for seven of the ten indicators in 2014 that were at least three-fourths as large as they had been in 1994. In addition, median family income for the highest-income group grew by $32,500 reaching $173,600 in 2014, and the corresponding disparities expanded for the middle-income, lower-middle-income, and lowest-income groups, respectively, to $113,300, $139,400, and $160,800.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Artiga S., & Cornachione, E. (2016). Trends in Medicaid and CHIP eligibility over time. Exhibit 1.2. from https://www.kff.org/report-section/trends-in-medicaid-and-chip-eligibility-over-time-section-1-eligibility-trends-by-group-2016-update/. Access 15 Feb 2018.

Bailey, M. J., & Dynarski, S. M. (2011). Inequality in postsecondary education. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Marnane (Eds.), Wither opportunity: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 117–132). New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Spencer Foundation.

Barnett, W. S., Carolan, M. E., Squires, J. H., & Clarke-Brown, K. (2014). State of preschool 2013: First look (NCES 2014–078). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014078.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Bivens, J. (2010). Worst economic crisis since the great depression? By a long shot. Economic Policy Institute: Economic Snapshot http://www.epi.org/publication/snapshot_20100127/. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Blumenthal, D., & Collins, S. R. (2014). Health care coverage under the affordable care act–a progress report. New England Journal of Medicine, 371, 275–281.

Brown, E. R., et al. (1999). Access to health insurance and health care for children in immigrant families. In D. J. Hernandez (Ed.), Children of immigrants: Health, adjustment, and public assistance (pp. 126–186). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Card, D. (2011). Origins of the unemployment rate: The lasting legacy of measurement without theory. American Economic Review, 101(3), 552–557.

CDC. (2015). Health measures in the 1997 redesigned National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Page last updated: November 9, 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_redesign.htm. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

CDC. (2018). Childhood obesity facts. Page last updated: January 29, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/obesity/facts.htm. .

Cherlin, A. (1999). Going to extremes: Family structure, children’s well-being, and social sciences. Demography, 36(4), 421–438.

Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (1994). Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Duncan, G.J., Kalil, A., & Ziol-Guest, K.M. (2016). Increasing inequality in parent incomes and children’s schooling. Revised paper presented at 2013 annual meeting of the population Association of America.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1974). Children of the great depression: Social change in life experience. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (1997). America’s children: Key national indicators of well-being. 1997. https://www.childstats.gov/pdf/ac1997/ac_97.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2018.

Flood, S., King, M., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J. R. (2017). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 5.0. [dataset]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V5.

Foundation for Child Development. (2011). Annual releases of the CWI. http://www.fcd-us.org/our-work/child-well-being-index-cwi/releases. Accessed 17 Jan 2011.

Heckman, J.J., & Materov, D.V. (2007). The productivity argument for investing in young children. http://jenni.uchicago.edu/human-inequality/papers/Heckman_final_all_wp_2007-03-22c_jsb.pdf. Accessed 23 Jan 2009.

Hernandez, D.J, & Marcartney, S.E. (2008). Measuring social disparities: A modified approach to the Index of Child Well-Being (CWI) for race-ethnic, immigrant-generation, and socioeconomic groups with new results for Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics. https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2016/04/FINALFULLReport.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018. See also https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2016/04/DisparitiesBrief.pdf.

Hernandez, D. J., & Marotz, K. G. (2012). Disparities in child well-being across income groups: Trends in the U.S. from 1985 to 2008. Child Indicators Research, 5(1), 93–121.

Hernandez, D.J., Denton, N.A., Macartney, S., & Blanchard, V.L. (2009a). Poverty and human resources for children in the United States and selected Rich countries.” In.J. Qvortrup (Ed.), Structural, historical, and comparative pespectives, Sociological studies of children and youth, Volume 12. (pp. 81-113). Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Hernandez, D.J., Macartney, S., & Blanchard, V.L. (2009b). Children in immigrant families in eight affluent countries: Their family, national, and international context. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (1997). Medicaid’s role for children. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/1997/10/medicaid-facts-medicaid-s-role-for-children-fact-sheet.pdf). Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2017). Where are states today? Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children, pregnant woman, and adults. Fact Sheet, Updated March 2017. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/where-are-states-today-medicaid-and-chip/. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Kalil, A. (2014). Inequality begins at home: The role of parenting in the diverging destinies of rich and poor children. In P. R. Amato, A. Booth, S. M. McHale, & J. Van Hook (Eds.), Diverging destinies: Families in an era of increasing inequality (pp. 63–82). New York: Springer.

Kalil, A., & Wightman, P. (2011). Parental job loss and children’s educational attainment in black and White middle-class families. Social Science Quarterly, 92(1), 57–78.

Kalil, A., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2008). Parental employment circumstances and children’s academic progress. Social Science Research, 37(2), 500–515.

Land, K.C. (2004). The foundation for child development index of Child Well-Being (CWI), 1975–2002, with projections for 2003, NY Foundation for Child Development. https://www.fcd-us.org/assets/2016/04/CWI_Report_2004New.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Land, K.C. (2005a). The foundation for child development index of Child Well-Being (CWI), 1975–2003 with projections for 2004. 2005 Report. New York: Foundation for Child Development. www.fcd-us.org/pdfs/2005cwidraftreport-final.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2005.

Land, K.C. (2005b). The 2005 index of Child Well-Being (CWI): Implications for policy makers. FCD Policy Brief, Series No. 2. New York: Foundation for Child Development.

Land, K.C. (2010). 2010 Child Well-Being Index (CWI). New York: Foundation for Child Development. http://www.fcd-us.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%202010%20CWI%20Annual%20Release.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Land, K. C., Lamb, V., & Mustillo, S. K. (2001). Child and youth well-being in the United States, 1975-1998: Some findings from a new index. Social Indicators Research, 56, 241–320.

Land, K.C. Lamb, V.L., Meadows, S.O., & Taylor, A. (2007). Measuring trends in child well-being: an evidence-based approach. Social Indicators Research, 80, 105–132.

Mashburn, A. J., et al. (2009). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79, 732–749.

McLanahan, S., & Sandefur, G. (1994). Growing up with a single parent: What hurts, what helps. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moiduddin, E., et al. (2012). Child outcomes and classroom quality in FACES 2009. OPRE Report 2012-37a. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Paradise, J. (2014). The impact of the Children’s Health Insurance Program: What does the research tell us? https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-impact-of-the-childrens-health-insurance-program-chip-what-does-the-research-tell-us/. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Reardon, S. F. (2011). The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In G. J. Duncan & R. J. Marnane (Eds.), Wither opportunity: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances (pp. 91–116). New York: Russell Sage Foundation and Spencer Foundation.

Reynolds, A. J., Temple, J. A., White, B. A. B., Ou, S.-R., & Robertson, D. L. (2011). Age 26 cost-benefit analysis of the child-parent center early education program. Child Development, 82(1), 379–404.

Rich, R. J. (2013). The great recession: December 2007–June 2009. Federal Reserve History. https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great_recession_of_200709. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

Ross, D. C., & Cox, L. (2000). Making it simple: Medicaid for children and CHIP income eligibility guidelines and enrollment procedures. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2000/09/2166.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Sandstrom, H., & Huerta, S. (2013). The negative effects of instability on child development: A research synthesis. Low-Income Working Families Discussion Paper 3, September 2013. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/412899-The-Negative-Effects-of-Instability-on-Child-Development-A-Research-Synthesis.PDF/. Accessed 19 November 2015.

Stevens, A. H., & Schaller, J. (2011). Short-run effects of parental job loss on children’s academic achievement. Economics of Education Review, 30(2), 289–299.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (1997). Chapter 1. Labor force data derived from the Current Population Survey. BLS Handbook of Methods. Bulletin 2490. https://www.bls.gov/opub/hom/pdf/homch1.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2015). U.S. Inflation Calculator, Consumer Price Index Data from 1913 to 2015. http://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/consumer-price-index-and-annual-percent-changes-from-1913-to-2008/. Accessed 27 Oct 2015.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018a). Data bases, tables & calculators by subject. Data tools. https://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018b). Consumer Price Index Research Series Using Current Methods (CPI-U-RS). https://www.bls.gov/cpi/research-series/alllessfe.pdf. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018c). The employment situation—December 2014 New Release, USDL-15-0001, Table A-15. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_01092015.pdf. Accessed 8 Feb 2018.

U.S. Census Bureau (2015). Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014. Current Population Reports, P60–252, Issued September 2015, by C. DeNavas-Walt &Proctor, B.D.

U.S. Census Bureau (2018a). Historical Income Tables: Families. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-income-families.html. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

U.S. Census Bureau (2018b). POV01. Age and Sex of All People, Family Members and Unrelated Individuals Iterated by Income-to-Poverty Ratio and Race. 2014. Below 200 Percent of Poverty. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-pov/pov-01.2014.html#par_textimage_30. Accessed 15 Feb 2018.

Yoshikawa, H., et al. (2013). Investing in our future: The evidence based on preschool education. Washington, DC/New York: Society for Research in Child Development and Foundation for Child Development.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge assistance provided by Suzanne Macartney, Hui-Shien Tsao, and Jean Mullin, access to computing resources provided by the Center for Social and Demographic Analysis at the University of Albany, State University of New York, and funding provided by the Foundation for Children Development. The authors have sole responsibility for the content and interpretation of the results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendixes

1.1 Appendix A: Comparing Components of Index of Parental Employment Insecurity

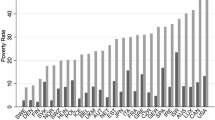

Results for specific components of the Index of Parental Employment Insecurity are presented in Appendix Table 2 and Fig. 13. Appendix Table 2 shows that children were more likely to have a parent who was unemployed during 2014 than to have a parent who was unemployed during March 2015, with differences for various income-quintile groups of 3–5% points. Similarly, children were more likely to have a parent who was underemployed during 2014 than to have a parent who was unemployed during March 2015, with differences for various income-quintile groups of 3–8% points. Thus, children in specific income-quintile groups were nearly or more than twice as likely to have unemployed parent or an underemployed parent in 2014 than to have a parent who was unemployed during March 2015. In addition, children in each income-quintile group were nearly as likely to have a hidden unemployed parent and nearly as likely to have an underemployed parent in March 2015 as to have an officially unemployed parent in March 2015.

Of course, some children are included in more than one of these categories either because one parent was included in the same or different categories in both 2014 and March 2015, or because a second parent in the home was included in the same or different categories during a period when the first parent was not included as employment insecure. Fig. 13 presents results which disentangle these categories. The results indicate for various income-quintile groups that the annual parental unemployment rate in 2014 (excluding children with a parent who was unemployed in March 2015) was nearly as larger than the rate of official parental unemployment in March 2015. Similarly, the rate of parental underemployment for 2014 and/or March 2015 (excluding children with an unemployed or hidden unemployed parent in 2014 and/or March 2015) was as larger or larger than the rate of official parental unemployment in March 2015. Finally, the rate of parental hidden unemployment for 2014 and/or March 2015 (excluding children with an unemployed parent in 2014 or March 2015) was nearly as large as the rate of official parental unemployment in March 2015. Thus, both this annual parental unemployment measure and this hidden parental underemployment measure contribute as much or more to the overall magnitude of the Index of Parental Employment Insecurity than does the official parental unemployment measure.

Appendix B: Calculating the Child Well-Being Index

The overall measure of child-well being presented here extends the approach of Land and colleagues to provide the basis for assessing both the magnitude and trends in disparities across children in the five income groups. Based on data for 28 key national indicators of child well-being that measure seven quality of life domains, the numerical value of the CWI for a given year is calculated in the four following steps (Land et al. 2001; Land 2005a, b).

First, assign a value of 100 to each indicator for the baseline year. Second, for each subsequent year calculate the percentage change from the baseline year for that indicator. Third, for a specific year equally weight the values for the indicators in a domain (calculate the arithmetic mean) to obtain the percentage average change for the domain as a whole. Fourth, for a specific year equally weight the values of each domain (calculated as the arithmetic mean of the values for the seven domains) to obtain the overall CWI value for the year. Thus, the CWI is an evidence-based measure indicating the average amount of change that was experienced by children across the seven domains between a baseline year and a subsequent year.

A corresponding set of CWIs can be calculated for each of the five child income-quintile groups by applying the same procedures to each group separately (Land et al. 2001; Land 2005a, b). Using this method, the results measure the average percentage change experienced by each group, using its own starting point as the baseline. However, because the baseline for each group is set to a value of 100, disparities cannot be assessed at the baseline year or subsequent years.

To directly assess the magnitude of disparities, and their trends through time, this research uses an alternative approach for specific income-quintile groups. A value of 100 is assigned to each indicator for the baseline year for the total population. Then for each specific group, the percent difference between that group and the total population is calculated for the baseline year. Thus, differences in values across income-quintile groups in the baseline year reflect their deviation from the mean, which is used to compare groups and measure disparities.

Using these results as the starting point, the subsequent steps in the original procedure are followed to calculate a modified CWI for each specific group. Thus, the value for a group-specific CWI for any subsequent year using this method reflects the extent to which that group differs on average in the quality of life from the total population in the baseline year, that is, the total population in the baseline year serves as a benchmark for measuring disparities. Furthermore, differences across groups in a specific year reflect the extent to which these groups differ from each other in that year, using the indicator values for the total population in the baseline year as the starting point. Two groups will, therefore, have CWI values that are equal in a given year, only if they are experiencing the same average quality of life. However, their CWI values will differ as long as there is a disparity between the groups in their average quality of life.

Results from this new approach contrast with the approach developed by Land et al. (2001), which leads to identical CWI values for two groups in a given year if these groups have experienced similar percent changes since the baseline year, even if disparities across groups remain large. But the new approach leads to identical CWI values for two groups in a given year only if the groups have identical levels of well-being.

For the present analysis, 10 indicators can be included in the CWI, because data are available only for these indicators to calculate rates for specific income groups. Three are indicators of family economic resources (median income, parental employment insecurity, and health insurance coverage), three are indicators of health (obesity, activity limitations, and very good or excellent health), two are indicators of social relations (one parent family and moved during the past year), and two are indicators of community engagement (Prekindergarten enrollment and idle or disconnected youth). These ten indicators and four domains of well-being are used to calculate values of the CWI for the present research.

Appendix C: Measuring Income Quintiles, Index of Parental Employment Insecurity, and Housing Costs

1.1 Income Quintiles

The March Current Population Survey (CPS) and its Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ACES) collect very detailed income data that provide the basis for precisely calculating family-income quintile values for children which are used in this report to assign each child to a specific family-income quintile group. The authors calculated these results for income quintiles from March CPS data provided by Flood et al. (2017). The most recent data analyzed for this report were collected in March 2015 for annual income in calendar 2014. March CPS data provide the basis for the analyses of income variables.

1.2 Index of Parental Employment Insecurity: Six Component Measures

The new Index of Parental Employment Insecurity is based on six specific employment concepts using data collected in the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the March Current Population Survey. The most recent data analyzed for this report were collected in March 2015. The index is calculated as the percent of children with at least one parent who, as indicated below, was classified as unemployed, as hidden unemployed, or as underemployed. March CPS data used by the authors to calculate these results were obtained from Flood, et al. (2015).

The first concept is official unemployment as of March, which classifies persons as unemployed, if they were not employed at the time of the March interview, and they had been looking for work during the past 4 weeks. The authors used the EMPSTAT variable to identify parents as officially unemployed in March.

The second concept is hidden unemployment as of March, which classifies persons as hidden unemployed, if they were not employed at the time of the March interview and had not looked for work during the past 4 weeks, but did want a job. The authors used the WANTJOB variable to identify parents as hidden unemployed in March.

The third concept is underemployment as of March, which classifies persons as underemployed, if they are working part-time but want a full-time job. The authors used the WHYPTLW variable to identify parents as underemployed if they reported working part time because they could only find part-time work or they worked part time because of slack work.

The fourth concept is unemployment during a calendar year, which classifies persons as unemployed, if they report looking for work or being on layoff for at least 1 week during the preceding calendar year. The authors used the WKSUNEM1 variable to identify parents as unemployed during a calendar year.

The fifth concept is hidden unemployment during a calendar year, which classifies persons as hidden unemployed, if they looked for work (and were not employed or on layoff) for at least 1 week during the preceding calendar year. The authors used the NWLOOKWK variable to identify parents as hidden unemployed during a calendar year.

The sixth concept is underemployment during a calendar year, which classifies persons as underemployed, if they are working part-time but want a full-time job. The authors used the variable WHYPTLY to identify parents as underemployed if they reported working part time because they could not find a full-time job or because of slack work during a calendar year.

1.3 Housing Costs

Housing costs were calculated with data from the 2013 American Housing Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau (2015), retrieved with assistance from Jean Mullin. Housing costs include mortgage or rent and utilities. Housing costs were reported in broad categories. The housing cost for the lowest-income group was calculated as the mean housing cost for households with incomes of Less Than $10,000 and with incomes of $10,000 to $19,000. The housing cost for the lower-middle-income group was calculated as the mean housing cost for households with incomes of $20,000 to $29,999, with incomes of $30,000 to $39,999, and with incomes of $40,000 to $49,999. The housing cost for the middle-income group was calculated as the mean housing cost for households with incomes of $50,000 to $59,000 and with incomes of $60,000 to $79,000. The most recent available data from the American Housing Survey were collected for 2013.

To measure income values across time that reflect real purchasing power, and to present housing costs consistent with income data, all results in this report are adjusted for inflation using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and presented as 2014 dollar values (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015).

It should be noted that monthly housing costs may be more volatile than annual housing costs because, for example, of differences in the cost of utilities during various months of the year, which introduces some noise into the annual estimates of housing costs calculated by multiplying monthly housing costs by 12. Such statistical noise is dampened, however, by the use of broad income categories in the American Housing Survey. It should also be noted that housing costs may change differentially depending on labor market conditions and other factors. The aim here is not, however, to assess the nature and magnitude of changes in housing costs, but instead to provide a contextual measure to shed light of the relative importance that changes in median family income had for various income-quintile groups, focusing on one of the most important expenditure categories of families.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, D.J., Napierala, J.S. Disparities in U.S. Parental Employment Insecurity and Child Well-Being Across Income Groups: Before, During, and After the Great Recession. Child Ind Res 13, 741–775 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09713-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09713-8