Abstract

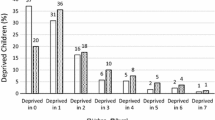

With recognition that poverty affects children in many ways that income-centric measures cannot demonstrate, there is increasing emphasis in multidimensional measurement of child poverty. Unfortunately, Zimbabwe has not kept pace with such important developments. This article applies a multidimensional deprivation approach to examine the extent and depth of child poverty and deprivation among children ages 5 years and below in Zimbabwe using 2015 Demographic and Health Survey data (N = 6418). Fourteen items are selected and tested for validity, reliability and additivity using robust statistical methods. Deprivation estimates are then produced at item level. Thereafter, the items are combined into a deprivation index and relevant deprivation estimates are produced. All deprivation estimates are distributed by gender and location. Results show that the commonest deprivation forms are early childhood development (78%), water (46%), healthcare (44%), sanitation (40%), shelter (30%) and nutrition (13%), respectively. The majority of deprived children in the study are deprived in two items and the least in ten or more items. However, 77% of all the children in the study are ‘absolutely poor’, that is, severely deprived of at least two items. While there are no significant share differences between male and female deprived children, all deprivations are highest in rural areas. Various policy strategies to help address these deprivations are suggested. Overall, the study contributes to the growing emphasis that child poverty is not all about income. It also highlights the importance of routine collection of better statistics to better inform anti-child poverty responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Education for under-five children is usually defined in terms of Early Childhood Development interventions like learning through play, information and stimulation, and social-emotional functioning (Boivin and Hertzman 2012).

Constitutive rights are those that denote material deprivation like lack of food, proper sanitation or safe drinking water. Instrumental rights (e.g., participation or protection) are immaterial, though they can be used to address constitutive rights. For instance, one cannot be said to be ‘poor’ because they were raped or their right to vote was violated. Constitutive rights speak better to child poverty in terms of material deprivation, while instrumental rights are more aligned to measures of child well-being (Abdu and Delamonica 2018; Jones and Sumner 2011).

UNICEF produces and/or regularly updates standard indicators for various aspects of children such as health, HIV and AIDS, nutrition, education and early childhood development, protection, participation, and so on. For in-depth review, see UNICEF Statistics and Monitoring page at https://www.unicef.org/statistics/index_24296.html.

There are different ways of establishing ‘suitability’. Common examples include Mack and Lansley’s (1985) consensual approach, global consensus (e.g., human rights instruments, development frameworks like SDGs and MDGs), existing research, secondary data assessment and expert opinion, among others.

In Townsend’s (1987) theory, poverty is due to sustained lack of resources (including income). In operationalizing resources under the ‘Bristol Approach’, an income variable is normally used simply because it is a good proxy of (but not equal to) resources. In the absence of an income variable in DHS, this study uses two income proxies. The use of two proxies is based on the need to reduce chances of making conclusions based on ‘noisy’ measurements.

Caregivers’ level of education and occupation are used to proxy income since DHS does not collect data on income. The DHS Wealth Index, which would have been an option, has been criticized for its limited theoretical and empirical basis and eugenic bias (Gordon and Nandy 2012). Education level and occupation are justified as they have been widely used in many studies to proxy income, economic status and social class (see Chaudry and Wime 2016; Bishaw 2014; Brewer and O’Dea 2012; Braveman 2010; Galobardes et al. 2006; Fields 1980).

‘Normal’ and ‘abnormal’ here are used for distinction’s and argument’s sakes and not in their strictest senses.

The DHS program collects immunization data only for children ages below 2 years because this tracks reception of the required vaccines in terms of WHO standards better than when looking at children as a whole.

References

Abdu, M., & Delamonica, E. (2018). Multidimensional child poverty: From complex weighting to simple representation. Social Indicators Research, 136, 881–905.

Agarwal, D., Misra, S. K., Chaudhary, S. S., & Prakash, G. (2015). Are we underestimating the real burden of malnutrition? An experience from community-based study. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 40(4), 268–272.

Alkire, S., & Roche, J. M. (2009). ‘Beyond headcount: The Alkire-Foster approach to multidimensional child poverty measurement’, child poverty insights. New York: UNICEF.

Atkinson, T., Cantillon, B., Marlier, E., & Nolan, B. (2002). Social indicators: The EU and social inclusion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Babbie, E. R., & Mouton, J. (2011). The practice of social research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bartlett, S. (2003). Water, sanitation and urban children: The need to go beyond “improved” provision. Environment and Urbanization, 15(2), 57–70.

Bejarano, I. F., Carrillo, A. R., Dipierri, J. E., Román, E. M., & Abdo, G. (2014). Composite index of anthropometric failure and geographic altitude in children from Jujuy (1 to 5 years old). Archivos Argentinos de Pediatría, 112(6), 526–531.

Berger, M. R., Fields-Gardner, C., Wagle, A., & Hollenbeck, C. B. (2008). Prevalence of malnutrition in human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome orphans in the Nyanza province of Kenya: A comparison of conventional indexes with a composite index of anthropometric failure. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(6), 1014–1017.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). ‘Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices, 2nd Edition’, Textbooks Collection: Book 3.

Bishaw, A. (2014). ‘Changes in areas with concentrated poverty: 2000 to 2010’, American Community Survey Reports, June 2014, ACS-27. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/acs/acs-27.pdf. Accessed 22 Mar 2018.

Boivin, M. and Hertzman, C. (2012). Early childhood development: Adverse experiences and developmental health. Royal society of Canada – Canadian academy of health sciences expert panel (with Barr, R., Boyce, T., Fleming, A., MacMillan, H., Odgers, C., Sokolowski, M. and Trocmé, N.). Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada.

Braveman, P. (2010). Measuring socioeconomic status/position (SES) in health research: We can do better. Presented at the IOM Workshop on Food Insecurity & Obesity, November 16, 2010. San Francisco, CA: Centre on Social Disparities in Health, University of San Francisco.

Brett, E. A. (2005). From corporatism to liberalization in Zimbabwe: Economic policy regimes and political crisis, 1980–97. International Political Science Review, 26(1), 91–106.

Brewer, M., & O’Dea, C. (2012). Measuring living standards with income and consumption: Evidence from the UK (IFS working paper W12/12). London: Economic and Social Research Council.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chaudry, A., & Wime, C. (2016). Poverty is not just an indicator: The relationship between income, poverty, and child well-being. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3), S23–S29.

Chikukwa, J. W. (2013). Zimbabwe: The end of the first republic. London: Author-House, UK Limited.

Chirisa, I., Mukarwi, L., & Matamanda, A. R. (2018). Sustainability in Africa: The service delivery issues of Zimbabwe. In R. Brinkmann & S. Garren (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of sustainability. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Coltart, D. (2008). A decade of suffering in Zimbabwe economic collapse and political repression under Robert Mugabe. Washington, DC: The Cato Institute.

Cresswell, J. W., & Plano-Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed method research (2nd ed.). SAGE: Thousand Oaks.

de Neubourg, C., Chai, J., de Milliano, M., Plavgo, I.,Wei, Z. (2012). Step-by-step guidelines to the multiple overlapping deprivation analysis (MODA). Working paper 2012–10. Florence: UNICEF Office of Research.

Ezeh, O. K., Agho, K. E., Dibley, M. J., Hall, J., & Page, A. N. (2014). Determinants of neonatal mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health, 14(521), 1–10.

Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

Fields, G. S. (1980). Education and income distribution in developing countries: A review of the literature. In T. King (Ed.), Education and income: A background study for world development (pp. 231–315). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Fink, G., Günther, I., & Hill, K. (2011). The effect of water and sanitation on child health: Evidence from the demographic and health surveys 1986–2007. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(5), 1196–1204.

Galobardes, B., Shaw, M., Lawlor, D. A., Lynch, J. W., & Smith, G. D. (2006). Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(1), 7–12.

Gold, O. P., & Ejughemre, U. J. (2013). Accelerating empowerment for sustainable development: The need for health systems strengthening in sub-Saharan Africa. American Journal of Public Health Research, 1(7), 152–158.

Gordon, D. (2006). The concept and measurement of poverty. In C. Pantazis, D. Gordon, & R. Levitas (Eds.), Poverty and social exclusion in Britain: The millennium survey. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Gordon, D., & Nandy, S. (2012). Measuring child poverty and deprivation. In A. Minujin & S. Nandy (Eds.), Global child poverty and well-being: Measurement, concepts, policy and action (pp. 57–101). Bristol: Policy Press.

Gordon, D., & Nandy, S. (2016). The extent, nature and distribution of child poverty in India. Indian Journal of Human Development, 10(1), 64–84.

Gordon, D., Nandy, S., Pantazis, C., Pemberton, S., & Townsend, P. (2003). Child poverty in the developing world. Bristol: The Policy Press.

Gordon, D., Nandy, S., Pantazis, C., Pemberton, S., & Townsend, P. (2016). Using multiple Indicator cluster survey (MICS) and demographic and health survey (DHS) data to measure child poverty. Bristol: University of Bristol and London School of Economics.

Government of Zimbabwe (2012). Zimbabwe 2012 millennium development goals progress report. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/english/MDG%20Country%20Reports/Zimbabwe/MDGR%202012final%20draft%208.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2015.

Government of Zimbabwe. (2013). Constitution of Zimbabwe of 2013. Harare: Government Printers. Retrieved from https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Zimbabwe_2013.pdf. Accessed 02 Aug 2018.

Guio, A. C., Gordon, D., Najera, H., & Pomati, M. (2017). Revising the EU material deprivation variables. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Hallerod, B., Rothstein, B., Nandy, S., & Daoud, A. (2013). Bad governance and poor children: A comparative analysis of government efficiency and severe child deprivation in 68 low- and middle-income countries. World Development, 48, 19–31.

Hamdok, A. A. (1999). A poverty assessment exercise in Zimbabwe. African Development Review, 11(2), 290–306.

Jones, N., & Sumner, A. (2011). Child poverty, evidence, and policy: Mainstreaming children in international development. Bristol: Policy Press.

Mack, J., & Lansley, S. (1985). Poor Britain. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Malaba, J. (2006). Poverty measurement and gender: Zimbabwe’s experience. Paper prepared for the inter-agency and expert group meeting on the development of gender statistics, 12–14 December 2006. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Manjengwa, J., Feresu, F., & Chimhowu, A. (2012a). Understanding poverty, promoting wellbeing and sustainable development – A sample survey of 16 districts of Zimbabwe. Harare: Institute of Environmental Studies.

Manjengwa, J., Kasirye, I. and Matema, C. (2012b). Understanding poverty in Zimbabwe: A sample survey in 16 Districts. Paper prepared for presentation at the Centre for the Study of African economies conference 2012 ‘Economic Development in Africa’, Oxford, United Kingdom, March 18–20, 2012.

Matutu, V. (2014). Zimbabwe agenda for sustainable socio-economic transformation (ZIMASSET) (2013–2018): A pipeline dream or reality? A reflective analysis of the prospects of the economic blue print. Research Journal of Public Policy, 1(1), 1–10.

Munro, L. T. (2015). Children in Zimbabwe after the long crisis: Situation analysis and policy issues. Development Southern Africa, 32(4), 477–493.

Nandy, S., & Miranda, J. (2008). Overlooking under-nutrition? Using a composite index of anthropometric failure to assess how underweight misses and misleads the assessment of under-nutrition in young children. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1963–1966.

Nandy, S., & Pomati, M. (2015). Applying the consensual method of estimating poverty in a low income African setting. Social Indicators Research, 124, 693–726.

Nandy, S., Irving, M., Gordon, D., Subramanian, S. V., & Davey-Smith, G. (2005). Poverty, child undernutrition and morbidity: New evidence from India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 83, 210–216.

Nunnally, J. C. (1981). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw Hill.

Pemberton, S. A., Gordon, D., Nandy, S., Pantazis, C., & Townsend, P. B. (2005). The relationship between child poverty and child rights: The role of indicators. In A. Minujin, E. Delamonica, & M. Komarecki (Eds.), Human rights and social policies for children and women: The multiple Indicator cluster survey (MICS) in practice (pp. 47–61). New York: New School University.

Pemberton, S., Gordon, D., & Nandy, S. (2012). Child rights, child survival and child poverty: The debate. In A. Minujin & S. Nandy (Eds.), Global child poverty and well-being: Measurement, concepts, policy and action (pp. 19–37). Bristol: Policy Press.

Pickering, A. J., & Davis, J. (2012). Freshwater availability and water fetching distance affect child health in sub-Saharan Africa. Environmental Science and Technology, 46(4), 2391–2397.

Reddy, S., & Pogge, T. (2008). How not to count the poor. In S. Anand, P. Segal, & J. E. Stiglitz (Eds.), Debates in the measurement of global poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rispel, L. C., Palha de Sousa, C. A. D., & Molomo, B. G. (2009). Can social inclusion policies reduce health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa? – A rapid policy appraisal. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 27(4), 492–504.

Roushdy, R., Sieverding, M., & Radwan, H. (2012). The impact of water supply and sanitation on child health: Evidence from Egypt. Cairo: Population Council.

Ruggeri Laderchi, C., Saith, R., & Stewart, F. (2003). Does it matter that we do not agree on the definition of poverty: A comparison of four approaches. Oxford Development Studies, 31(3), 233–274.

Rutstein, S. O., & Johnson, K. (2004). DHS comparative reports no. 6 – The DHS wealth index. Calverton: The DHS Program, ORC Macro.

Rutstein, S.O. and Rojas, G. (2006). Guide to DHS statistics: Demographic and Health Surveys Methodology. Calverton: ORC macro demographic and health surveys. Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/DHSG1/Guide_to_DHS_Statistics_29Oct2012_DHSG1.pdf. Accessed 06 Dec 2017.

Schaay, N., & Sanders, D. (2011). International perspective on primary healthcare over the past 30 years. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape, School of Public Health.

Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107–120.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. Middlesex: Penguin Books Ltd.

Townsend, P. (1987). Deprivation. Journal of Social Policy, 16(2), 125–146.

Townsend, P. (2002). Poverty, social exclusion and social polarisation: The need to construct an international welfare state. In P. Townsend & D. Gordon (Eds.), World poverty: New policies to defeat an old enemy (pp. 3–24). Bristol: The Policy Press.

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 769.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2007). Global study on child poverty and disparities 2007–2008 guide. New York: UNICEF Global Policy Section, Division of Policy and Planning.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2017a). The state of the world’s children 2016: A fair chance for every child. New York: UNICEF.

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2017b). UNICEF data: Monitoring the situation of children and women. New York: UNICEF Retrieved from http://data.unicef.org. Accessed 11 Apr 2018.

United Nations Children’s fund and World Bank. (2016). Ending extreme poverty: A focus on children. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Ending_Extreme_Poverty_A_Focus_on_Children_Oct_2016.pdf. Accessed 09 Jan 2018.

United Nations Children’s Fund–United Kingdom. (2014). Child rights partners: Putting children’s rights at the heart of public services – Information booklet. London: UNICEF-UK Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org.uk/child-rights-partners/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2016/11/Unicef-UK_CRP-information-booklet_14.11.16.pdf. Accessed 29 Sept 2016.

United Nations Children’s Fund–Zimbabwe. (2016). The child poverty in Zimbabwe: A multiple overlapping deprivation analysis of multiple Indicator cluster survey 2014. Harare, UNICEF Zimbabwe. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/esaro/2016-UNICEF-Zimbabwe-Child-Poverty.pdf. Accessed 25 July 2017.

United Nations Children’s Fund–Zimbabwe. (2018). Investing in Zimbabwe’s children: Building resilience and accountability for a brighter future. Harare: UNICEF Zimbabwe Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/UNICEF_in_Zimbabwe_web.pdf. Accessed on 13 June 2018.

United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. (1991). General comment 3: The nature of States parties’ obligations. Report on the fifth session, Supp. No. 3, annex III, U.N. doc. E/1991/23.

United Nations Economic, & Social Council. (2016). Report of the inter-agency and expert group on sustainable development goal indicators E/CN.3/2016/2. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Council Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/47th-session/documents/2016-2-iaeg-sdgs-e.pdf. Accessed 19 Mar 2018.

United Nations General Assembly. (1996). Report of the world summit for social development, Copenhagen 6–12 march 1995. New York: United Nations Retrieved from https://undocs.org/A/CONF.166/9. Accessed 11 Dec 2015.

United Nations General Assembly. (2007). Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 19 December 2006 – The rights of the child (a/RES/61/146). New York: United Nations Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_61_146.pdf. Accessed 07 Sept 2016.

White, H., Leavy, J., & Masters, A. (2002). Comparative perspectives on child poverty: A review of poverty measures. Working paper no 1. London: Young lives and Save the Children Fund UK.

World Bank. (2017). Country poverty brief: Sub-Saharan Africa: Zimbabwe, October 2017. Washington, DC: World Bank Retrieved from http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Archives-2017/Global_POV_SP_CPB_ZWE.pdf. Accessed 16 Feb 2018.

World Health Organization. (2006). WHO multicentre growth reference study group: WHO child growth standards: Length/ height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. Geneva: WHO Retrieved from http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/technical_report/en/index.html. Accessed 21 Aug 2013.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2012). Zimbabwe population census 2012 national report. Harare: Population Census Office Retrieved from http://www.zimstat.co.zw/sites/default/files/img/publications/Population/National_Report.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2018.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2015). Zimbabwe multiple Indicator cluster survey 2014: Final report. Harare: ZIMSTAT Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/Zim_MICS5_Final_Report_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2017.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2016). Poverty analysis: Poverty datum lines – July 2016. Harare: ZIMSTAT. Retrieved from https://t3n9sm.c2.acecdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/poverty_07_2016.pdf. Accessed 10 Feb 2017.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency. (2018). Zimbabwe GDP annual growth rate, 1961–2018. Trading economics application programming interface. Retrieved from https://tradingeconomics.com/zimbabwe/gdp-growth-annual. Accessed 03 June 2018.

Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency and ICF International. (2016). Zimbabwe demographic and health survey 2015: Final report. Rockville: ZIMSTAT and ICF International Retrieved from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR322/FR322.pdf. Accessed 03 June 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

This study was conducted with financial and material support from OPEC Fund for International Development (OFID) in Vienna, Austria, through the 2017 OFID Scholarship Annual Award (Grant No:13034GR). Access and permission to use the 2015 Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey for purposes of this study was granted by ICF International’s Demographic and Health Survey Program in Maryland, USA. Otherwise, I have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 115 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Musiwa, A.S. Extent and Depth of Child Poverty and Deprivation in Zimbabwe: a Multidimensional Deprivation Approach. Child Ind Res 13, 885–915 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09656-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09656-0