Abstract

Primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma (PEL-LL) shows a unique clinical presentation, characterized by lymphomatous effusions in the body cavities. PEL-LL may be associated with hepatitis C virus infections and fluid overload states; and owing to its rarity, no standard therapies have been established. We report a case of a 55-year-old woman who developed PEL-LL during treatment with dasatinib, for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). She presented to our hospital with dyspnea lasting for approximately a month and showed pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions. The pericardial effusion was exudative, and cytopathological and immunophenotypic examinations showed numerous CD 20-positive, large atypical lymphoid cells, which were also positive for the Epstein-Barr virus gene. No evidence of lymphadenopathy or bone marrow infiltration was found. We diagnosed PEL-LL, immediately discontinued dasatinib, and performed continuous drainage of the pericardial effusions. Complete response was achieved, and remission was maintained for 15 months. Two months after discontinuation of dasatinib, she was administered imatinib and a deep molecular response for the CML was maintained. PEL-LL occurring during dasatinib treatment is rare. We compared the results of previous reports with this case, and found that early diagnosis of PEL-LL, discontinuation of dasatinib, and sufficient drainage can improve the prognosis of PEL-LL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a rare non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that shows unique clinical presentations such as lymphomatous effusions in the pericardium, pleura, and peritoneum without a primary tumor mass. It is also characterized by infection with human herpesvirus type-8 (HHV-8) [1, 2]. On the other hand, HHV-8-negative effusion-based lymphoma is classified as PEL-like lymphoma (PEL-LL). Patients with PEL-LL are generally older and have a better prognosis than those with PEL [3,4,5,6]. Previous reports have shown that PEL-LL may be associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and fluid overload states such as cirrhosis, heart failure, and protein-losing enteropathy [5, 7].

Dasatinib is a multiple tyrosine kinases inhibitor, including BCR-ABL, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-β, c-KIT, SRC, and others. It is specifically effective in BCR-ABL-driven diseases such as chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and acute lymphoblastic leukemia [8, 9]. Pleural and pericardial effusions are common adverse events in patients undergoing dasatinib treatment. The patients are managed by dose interruption, dose reduction, and diuretic and steroid administration [10,11,12].

PEL-LL during dasatinib treatment is very rare, with only four cases reported previously [13,14,15]. Herein, we present the case of a 55-year-old woman who was diagnosed with PEL-LL during treatment of CML with dasatinib and achieved complete remission by continuous drainage alone. The cases reported in literature showed clinical courses different from our case; therefore, we reviewed them and discussed their clinical characteristics.

Case

A 55-year-old woman presented to our hospital with leukocytosis. She was diagnosed with CML in June 2019 and treated with dasatinib (70 mg/day). Mild bilateral pleural effusion was observed in August 2019. She received diuretics without thoracentesis, and the bilateral pleural effusion promptly disappeared. She achieved a deep molecular response (DMR) in January 2020.

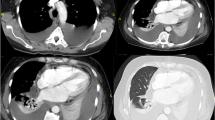

In October 2020, she presented to the emergency room after experiencing dyspnea on exertion for one month. Physical examination revealed sinus tachycardia, hypoxia (oxygen saturation, 93% in air), and lower leg edema. Chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) revealed pericardial and bilateral pleural effusion (Fig. 1A, B). Lymphadenopathy was not observed. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) revealed massive pericardial effusion and right ventricular diastolic collapse. Laboratory examination showed slightly elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels (268 U/L), but the soluble interleukin-2 receptor levels were within the normal range (373 U/mL). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for serum hepatitis B virus, HCV, human immunodeficiency virus, and HHV-8 showed negative results. IgM and IgG anti-viral capsid antigen titers were consistent with previous infection. The patient still maintained the DMR for CML treatment. Subsequently, pericardiocentesis showed a bloody and exudative pericardial effusion. The LDH and adenosine deaminase levels in the pericardial effusion were elevated to 4833 U/L and 169 U/L, respectively. Cytopathological examination showed numerous large atypical lymphoid cells, which were immunohistochemically positive for CD20, Epstein-Barr encoding region (EBER), and the kappa chain, and mildly positive for TP53.The Ki-67 proliferation index was high (Fig. 2A–C). Upon performing PCR, malignant cells showed a rearrangement in the immunoglobulin heavy (IgH) chain genes. No lymphoma cells were found in the peripheral blood or bone marrow. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with PEL-LL.

The patient discontinued dasatinib and underwent continuous pericardial drainage for 4 days. TTE revealed that the pericardial effusion had almost disappeared the following day. Dyspnea on exertion and lower leg edema improved; chest radiography showed that bilateral pleural effusion had disappeared without drainage; and the patient was discharged on the sixth day after admission. In November 2020, whole-body positron emission tomography-CT showed a complete metabolic response for the PEL-LL. Imatinib was started in December 2020, and the DMR for CML treatment was maintained in April 2022, without relapse of PEL-LL (Fig. 1C).

Discussion

The findings of this case suggest that immediate discontinuation of dasatinib and continuous drainage could be an effective treatment for PEL-LL. In addition, pleural and pericardial effusions related to dasatinib could induce PEL-LL.

To the best of our knowledge, only four cases have reported a diagnosis of PEL-LL in patients showing effusions following dasatinib treatment for CML (Table 1) [13,14,15]. EBER was positive only in one case (case 3). In three cases (cases 1–3) treatment with dasatinib was continued for more than 1 year prior to effusion appearance. In one case (case 4), PEL-LL was incidentally diagnosed during thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer, and the disease duration of PEL-LL was not described. The patients in cases 1 and 3 were treated with systemic chemotherapy resulting in complete response and complete metabolic response, respectively. However, in cases 2 and 4, the patients were treated with only drainage and steroids, resulting in relapse. The patient in case 4 died due to coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia during treatment for relapsed PEL-LL. The patient in case 1 achieved DMR before tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) discontinuation and lost major molecular response for CML during treatment of PEL-LL. In contrast, in cases 3 and 4, the withdrawal period of TKIs was short and DMR was maintained after the treatment of PEL-LL.

Our case showed two primary differences from the previous cases. First, our patient was treated with continuous drainage for 4 days until the absence of pericardial effusion was confirmed. Some studies have reported that PEL-LL is treated successfully with drainage alone [16,17,18,19]. In these cases, three patients received continuous drainage similar to the patient in our case [16, 17]. These reports suggest that continuous drainage would lead to a sufficient reduction in lymphoma cells. PEL-LL is often diagnosed in older individuals; therefore, treatment with drainage alone is advantageous in terms of fewer complications. Second, dasatinib was immediately discontinued in our patient because she experienced dyspnea and pericardial effusion. Early diagnosis of PEL-LL and immediate withdrawal of dasatinib can improve the prognosis for PEL-LL and reduce the time required to restart TKIs, leading to a good prognosis for CML.

The mechanism underlying the onset of PEL-LL induced by dasatinib treatment remains unclear. Pleural and pericardial effusions are common dasatinib-associated adverse events. Some studies have reported that these adverse events may occur through the inhibition of PDGFR-β [20, 21]. 2 reports have suggested a relationship between PEL-LL and fluid overload [5, 6]. In this case, fluid overload caused by dasatinib might have led to the development of PEL-LL. Next, in this case, immunostaining revealed that the lymphoma cells were positive for EBER. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent infection contributes to EBV-mediated B cell transformation and lymphomagenesis [22]. Although large atypical lymphoid cells that were positive for CD20 and EBER disappeared only by drainage, these cells were also positive for IgH rearrangement and immunoglobulin light-chain restriction, and we thus diagnosed with PEL-LL based on their clonality. Dasatinib has been shown to suppress effector memory T-cell function in vitro [23, 24], and some reports have described EBV activation and the development of lymphoproliferative disorder (LPD) during treatment with dasatinib [25, 26]. The immunosuppression caused by dasatinib may lead to the development of EBV-positive PEL-LL-like LPD. In addition, some studies have reported that effusion-related dasatinib has an immune-related pathogenesis based on the high lymphocyte count in pleural fluid, lymphocytic infiltration in pleural biopsy, lymphoproliferation in peripheral blood, and response to steroids [27, 28]. Localized immunosuppression induced by chronic inflammatory stimulation has the potential to cause growth of EBV-infected B cells [29]. In this case, immune-related pericardial effusion might have caused chronic inflammation, localized immunodepression, and growth of EBV-infected B cells, resulting in PEL-LL.

Dasatinib-related pleural and pericardial effusion were often improved by reduction of dasatinib and administration of diuretics and steroids. When repeated pleural and pericardial effusion are observed during dasatinib treatment, PEL-LL should be considered as a differential diagnosis. When thoracentesis is performed, it is important to confirm the results of cytological and immunophenotypic examinations. Early diagnosis of PEL-LL, discontinuation of dasatinib, and sufficient drainage could improve the prognosis of both PEL-LL and CML, as noted in our patient. More cases and data are needed to understand the mechanisms and risks of PEL-LL onset during dasatinib.

References

Gaidano G, Carbone A. Primary effusion lymphoma: a liquid phase lymphoma of fluid-filled body cavities. Adv Cancer Res. 2001;80:115–46.

Yiakoumis X, Pangalis GA, Kyrtsonis MC, Vassilakopoulos TP, Kontopidou FN, Kalpadakis C, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma in two HIV-negative patients successfully treated with pleurodesis as first-line therapy. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:271–6.

Nussinson E, Shibli F, Shahbari A, Rock W, Elias M, Elmalah I. Primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:857–62.

Kaji D, Ota Y, Sato Y, Nagafuji K, Ueda Y, Okamoto M, et al. Primary human herpesvirus 8-negative effusion-based lymphoma: a large B-cell lymphoma with favorable prognosis. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4442–50.

Alexanian S, Said J, Lones M, Pullarkat ST. KSHV/HHV8-negative effusion-based lymphoma, a distinct entity associated with fluid overload states. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:241–9.

Wu W, Youm W, Rezk SA, Zhao X. Human herpesvirus 8-unrelated primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma report of a rare case and review of 54 cases in the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140:258–73.

Paner GP, Jensen J, Foreman KE, Reyes CV. HIV and HHV-8 negative primary effusion lymphoma in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:1811–4.

Rousselot P, Coudé MM, Gokbuget N, Passerini CG, Hayette S, Cayuela JM, et al. Dasatinib and low-intensity chemotherapy in elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive all. Blood. 2016;128:774–82.

Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, Mayer J, Boqué C, et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the dasatinib versus imatinib study in treatment-naïve chronic myeloid leukemia patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2333–40.

Masiello D, Gorospe G, Yang AS. The occurrence and management of fluid retention associated with TKI therapy in CML, with a focus on dasatinib. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:1–6.

Hughes TP, Laneuville P, Rousselot P, Snyder DS, Rea D, Shah NP, et al. Incidence, outcomes, and risk factors of pleural effusion in patients receiving dasatinib therapy for philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia. Haematologica. 2019;104:93–101.

Tinsley SM. Safety profiles of second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:1207–18.

Kojima M, Nakamura N, Amaki J, Numata H, Miyaoka M, Motoori T, et al. Human herpesvirus 8-unrelated primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma following tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment for chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2017;57:69–73.

Miyagi D, Chen WY, Chen BJ, Su YZ, Kuo CC, Karube K, et al. Dasatinib-related effusion lymphoma in a patient treated for chronic myeloid leukaemia. Cytopathology. 2020;31:602–6.

Fiori S, Todisco E, Ramadan S, Gigli F, Falco P, Iurlo A, et al. HHV8-negative effusion-based large B cell lymphoma arising in chronic myeloid leukemia patients under dasatinib treatment: a report of two cases. Biology (Basel). 2021;10:1–7.

Terasaki Y, Yamamoto H, Kiyokawa H, Okumura H, Saito K, Ichinohasama R, et al. Disappearance of malignant cells by effusion drainage alone in two patients with HHV-8-unrelated HIV-negative primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2011;94:279–84.

Terasaki Y, Okumura H, Saito K, Sato Y, Yoshino T, Ichonohasama R, et al. HHV-8/KSHV-negative and CD20-positive primary effusion lymphoma successfully treated by pleural drainage followed by chemotherapy containing rituximab. Intern Med. 2008;47:2175–8.

Nakatsuka SI, Kimura H, Nagano T, Fujita M, Kanda T, Iwata T, et al. Self-limited effusion large B-cell lymphoma: two cases of effusion lymphoma maintaining remission after drainage alone. Acta Haematol. 2013;130:217–21.

Adiguzel C, Bozkurt SU, Kaygusuz I, Uzay A, Tecimer T, Bayik M. Human herpes virus 8-unrelated primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma: report of a rare case and review of the literature. APMIS. 2009;117:222–9.

Quintás-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Borthakur G, Bruzzi J, Munden R, et al. Pleural effusion in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia treated with dasatinib after imatinib failure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3908–14.

Goldblatt M, Huggins JT, Doelken P, Gurung P, Sahn SA. Dasatinib-induced pleural effusions: a lymphatic network disorder? Am J Med Sci. 2009;338:414–7.

Kanda T. EBV-encoded latent genes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1045:377–94.

Schade AE, Schieven GL, Townsend R, Jankowska AM, Susulic V, Zhang R, et al. Dasatinib, a small-molecule protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, inhibits T-cell activation and proliferation. Blood. 2008;111:1366–77.

Weichsel R, Dix C, Wooldridge L, Clement M, Fenton-May A, Sewell AK, et al. Profound inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell effector functions by dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2484–91.

Yamada A, Katagiri S, Moriyama M, Asano M, Suguro T, Yoshizawa S, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease during dasatinib treatment occurred 10 years after umbilical cord blood transplantation. J Infect Chemother. 2021;27:1076–9.

Wölfl M, Langhammer F, Wiegering V, Eyrich M, Schlegel PG. Dasatinib medication causing profound immunosuppression in a patient after haploidentical SCT: Functional assays from whole blood as diagnostic clues. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:875–7.

Mustjoki S, Ekblom M, Arstila TP, Dybedal I, Epling-Burnette PK, Guilhot F, et al. Clonal expansion of T/NK-cells during tyrosine kinase inhibitor dasatinib therapy. Leukemia. 2009;23:1398–405.

Bergeron A, Réa D, Levy V, Picard C, Meignin V, Tamburini J, et al. Lung abnormalities after dasatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia: A case series. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:814–8.

Copie-Bergman C, Niedobitek G, Mangham DC, Selves J, Baloch K, Diss TC, et al. Epstein-Barr virus in B-cell lymphomas associated with chronic suppurative inflammation. J Pathol. 1997;183:287–92.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and medical staff for their contributions to this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with these guidelines. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Okayama City Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

About this article

Cite this article

Hayashino, K., Meguri, Y., Yukawa, R. et al. Spontaneous regression of dasatinib-related primary effusion lymphoma-like lymphoma. Int J Hematol 117, 137–142 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-022-03449-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-022-03449-y