Abstract

Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.), a warm-season perennial grass, is an important bioenergy crop candidate because it produces high biomass yields on marginal lands and on reclaimed surface mined sites. In companion studies, dry matter (DM) yields for Cave-in-Rock, Shawnee, and Carthage cultivars varied from 4.2 to 13.0 Mg ha−1averaged over 6 years at the reclaimed Hampshire site, and fertilization increased yields of Cave-in-Rock at Black Castle and Coal Mac sites from 0.3 to 2 Mg ha−1 during the first 3 years. The objective of these experiments was to compare the impacts of cultivar and soil amendments on biomass quality and theoretical ethanol production of switchgrass grown on surface mines with differing soil characteristics. Biomass quality was determined for fiber, ash, lignin, digestibility, and carbohydrate contents via near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy, and carbohydrates were used to calculate theoretical ethanol yield (TEY; L Mg−1) and multiplied by biomass yield to calculate theoretical ethanol production (TEP; L ha−1). Cultivars at the Hampshire site did not differ in TEY and ranged from 426 to 457 L Mg−1. Theoretical ethanol production from Cave-in-Rock at Hampshire was 7350 L ha−1, which was higher than other cultivars because of its greater biomass production. This TEP was higher than in other studies which predicted 4000 to 5000 L ha−1. At the Black Castle and Coal Mac sites, fertilizer applications slightly affected biomass quality of switchgrass and TEY, but provided greater TEP as a function of increased yield. Similar to other findings, total switchgrass biomass production has more impact than compositional differences on TEP, so maximizing biomass production is critical for maximizing potential biofuel production. With appropriate soil substrates, fertilization, planning, and management, large areas of reclaimed surface mines can be converted to switchgrass stands to produce high biomass quality and yields to support a bioethanol industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Switchgrass is a model crop for cellulosic ethanol because of high biomass production potential and compositional characteristics [8]. Switchgrass ethanol yield is improved with greater carbohydrate fractions, fewer lignin constituents, and less metals [9, 34]. The major fermentable sugars in hydrolyzed grass biomass are glucose and xylose, while arabinose, galactose, and mannose contribute significantly less [1, 7, 10, 13, 27, 35]. Therefore, simple conversion calculations can be used to predict ethanol yield using the hexose (glucose, mannose, and galactose) and pentose (xylose and arabinose) sugars from hydrolyzed switchgrass biomass cell walls [6, 35].

Switchgrass composition demonstrates significant annual and spatial variation [29]. This can be due to precipitation [15], temperature [1], and management [14]. Within-field variation and small changes in soil properties do not seem to affect switchgrass composition because individual fields are subject to similar temperatures, precipitation, and harvest management [29]. This is useful in practice because biorefineries can run fewer analyses of switchgrass if shipments come to the refinery from harvests of the same fields.

Many studies have reported differences among switchgrass cultivars in ligno-cellulosic composition [2, 5, 23, 29], while others have shown similarities among cultivars [20, 39]. For example, Schmer et al. [29] showed that Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee had higher total hexose concentrations than the cultivar Trailblazer. Trailblazer had a higher theoretical ethanol yield (TEY; L Mg−1) compared to Shawnee at one of three sites in their study. Cultivar differences were also evident for theoretical ethanol production (TEP; L ha−1) at two sites because of differences in biomass yield. Although compositional differences among cultivars may affect ethanol yield on a mass basis (L Mg−1), greater aboveground biomass may have a greater influence on ethanol production per land area (L ha−1) [21, 23, 29, 35].

Wet chemical analysis to determine carbohydrate characteristics of biomass samples is expensive and time-consuming. The cost of producing a comprehensive profile of carbohydrate and other constituents as performed by Vogel et al. [35] is approximately $2000 per switchgrass sample [12, and personal communication, K. Vogel and M. Casler]. Although a biorefinery does not need complete characterization of biomass traits and cell wall components to determine quality for ethanol production, analyzing large numbers of samples can become very costly. Typical biomass quality traits required by a biorefinery are ash, structural and soluble carbohydrate content, lignin, and moisture [6, 25]. Analyzing each individual sugar requires a significant amount of time, equipment, and money.

Recent research has demonstrated the feasibility of determining the chemical constituents of bioenergy feedstocks with near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (NIRS) rather than by traditional laboratory wet chemistry techniques [17, 22, 34, 35, 38]. Biomass samples for prediction equation development are selected to represent the range of spectral, cultural, and compositional characteristics, such as maturity and crop management, in the population of interest [32, 35]. Calibration sets of paired spectra and reference wet chemical data are used with chemometrics software to develop prediction equations for rapid, cost-effective analysis of biomass constituents [35, 38]. Currently, there are no research results regarding compositional analysis of switchgrass grown on reclaimed surface mines by wet chemistry or NIRS.

Our first objective was to determine if biomass composition, TEY, and TEP varied among three switchgrass cultivars grown on a surface mine. Previous experiments showed that aboveground biomass levels differed among cultivars and reclamation methods [3], but higher biomass yields may not translate into better biomass quality for ethanol production. A second objective was to determine the effect of fertilizer applications on Cave-in-Rock switchgrass composition, TEY, and TEP from reclaimed surface mine sites.

Materials and Methods

Composition of switchgrass biomass was evaluated from four reclaimed sites in West Virginia. Site descriptions, biomass collection, and yield data were reported previously [3] and are summarized below. To determine compositional differences among three switchgrass cultivars in experiment 1, biomass samples were collected for NIRS analysis from Hampshire, a site where annual biomass dry matter (DM) yields were up to 19 Mg ha−1. Compositional analysis of samples from Hobet via NIRS was unsuccessful because spectra were outside the population structure of our calibration set, and therefore, the data were not used further. To determine compositional differences of Cave-in-Rock grown with different fertilizer and mulch treatments in experiment 2, biomass samples were collected from Black Castle and Coal Mac sites.

Brief Description of Sites

Experiment 1

Reclamation at Hampshire (39.4° N,79.1° W) was completed in 1996 and mine soils were covered with 0.3 m of topsoil, and three applications of lime-treated sludge from the Luke, MD, municipal wastewater treatment plant were made in 1998, 2003, and 2008, each at a rate of 225 Mg (dry) ha−1. The application of topsoil and sludge provided favorable soil properties which greatly enhanced revegetation potential. Nine 0.4-ha plots were laid out in 2008, and three upland cultivars of switchgrass, replicated three times, were assigned to plots in a completely randomized design. Cave-in-Rock, Carthage, and Shawnee were broadcast-seeded in individual plots at 11.2 kg pure live seed ha−1. Six sampling points were randomly chosen within each plot, and aboveground biomass within a 0.21-m2 quadrat was clipped to 10-cm stubble height at post-anthesis stage in October 2012 and 2013 to determine yield. Biomass was not removed from plots annually, and biomass collected from previous year’s growth was less than 5 % of sample mass.

Experiment 2

Sites at Coal Mac (37.7° N, 82.0° W) and Black Castle (38.1° N, 81.7° W) were reclaimed in early 2011, but Coal Mac was reclaimed with 0.6 to 0.9 m of topsoil and Black Castle had 0.2 to 0.3 m of applied topsoil. Cave-in-Rock switchgrass was planted at the same rate as in experiment 1, and planting, fertilizing, and mulching occurred in June 2011. At both sites, four treatments were assigned to plots in a randomized complete block design with five 0.4-ha blocks:

-

1.

No fertilizer, light mulch: control; 1.5 Mg ha−1 application of hydromulch (dry wt)

-

2.

Low fertilizer, light mulch: 34 kg N-P2O5-K2O ha−1 and 1.5 Mg ha−1 application of hydromulch

-

3.

Low fertilizer, heavy mulch: 34 kg N-P2O5-K2O ha−1 and 3.0 Mg ha−1 application of hydromulch

-

4.

High fertilizer, light mulch: 68 kg N-P2O5-K2O ha−1 and 1.5 Mg ha−1 application of hydromulch

Commercial 10-10-10 fertilizer was applied at appropriate rates to plots. Hydromulch, a paper-based product, was used to simulate hydroseeding techniques for revegetation. Three sampling points were randomly chosen within each plot, and aboveground biomass within a 0.21-m2 quadrat was clipped at each point as in experiment 1 to determine biomass yield. Biomass was not removed from plots annually, and biomass collected from previous year’s growth was less than 1 % of sample mass at these sites.

Biomass Preparation and NIRS Analysis

Clipped biomass samples were dried at 60 °C to constant weight and ground to pass a 2-mm screen of a cutting mill and a 1-mm screen of a cyclone mill. Sample spectra were obtained on a scanning monochromator (SpectraStar 2400 RTW, Unity Scientific, Brookfield, CT) as the reciprocal log of reflectance (log 1/R) at 1-nm increments over a range of 1250 to 2349 nm. Subsequent predictions of sample composition were made with UCal 3.0 chemometrics software (Unity Scientific, Brookfield, CT). Spectra were standardized with a data file that spectrally matched our instrument to a master instrument (FOSSModel 6500, FOSS North America, Eden Prairie, MN) managed by the NIRS Forage and Feed Testing Consortium (NIRSC, Hillsborough, WI) and from which UCal prediction equations for compositional analysis were obtained. A switchgrass bioenergy equation was used from a calibration database developed by Vogel et al. [35] with samples grown on agricultural sites in the Great Plains region of the USA and representing diverse varieties, locations, and harvesting techniques and timing. A second forage compositional equation was used, which was developed by the NIRSC (13ghu24.prd) from a grass-hay database containing cool- and warm-season grasses including switchgrass. Summary statistics for these equations developed with modified partial least squares regression are in Vogel et al. [35] and online [24]. Reference wet chemical methods for switchgrass bioenergy calibration samples are described in Vogel et al. [35]. Those for NIRSC grass-hay equation samples include amylase-treated neutral detergent fiber (aNDF), ash, acid detergent lignin (ADL), and 48-h in vitro NDF digestibility (NDFD48) as described in Peters [26].

Samples were considered to be well-represented by prediction equation calibration sets if global and neighborhood distances (GD and ND) calculated for each sample were ≤3 and ≤1.2, respectively, for individual constituents [32]. Samples that exceeded these limits for a constituent were considered outliers relative to the calibration dataset and predicted values for those constituents were excluded from comparisons of experimental treatments and calculations of TEY and TEP. For Hampshire, 10 % of the samples were discarded because they were considered outliers, while 22 and 11 % of samples were discarded for Black Castle and Coal Mac, respectively. As noted, all samples from Hobet were outliers and not used in this analysis.

Estimation of Theoretical Ethanol Yield and Ethanol Production

Data for individual sugars obtained from compositional analysis with NIRS (Table 1) were used to predict TEY and TEP. Concentrations of cell wall carbohydrates used in Vogel et al. [35] and predicted by the NIRSC bioenergy equation were as polymeric forms: glucan (GLC), galactan (GAL), mannan (MAN), xylan (XYL), and arabinan (ARA) (Table 1 and B. Dien, personal communication). Three methods were used to estimate TEY and TEP (Table 2). The first was a Vogel et al. NIRS switchgrass bioenergy equation [35], which is more comprehensive and is based on cell wall and nonstructural carbohydrate concentrations (method 1). The second method from Dien [6] is a simplification of Method 1 and includes only the main cell wall hexose and pentosepolysaccharides which can be hydrolyzed to fermentable sugars. For samples from Black Castle and Coal Mac for which all constituents could not be predicted within acceptable GD and/or ND limits with the switchgrass bioenergy equation, a third method was used, which is a simplified version of Method 2. Method 3 was based only on cell wall glucan and xylan because concentrations of these constituents could be more reliably predicted than those of other cell wall sugars at these sites. Concentrations of sugars in equations are in mg g−1.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed as a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with year as the repeated variable, using a mixed-model procedure of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) with sites, cultivars, and years as fixed effects [33]. Data met assumptions of normal distributions for ANOVA according to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test [31]. For both experiments, data were analyzed by the least square (LS) means analysis with Tukey-Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons. The LS means and standard errors are presented in the tables. For experiment 2, blocks within sites (Black Castle and Coal Mac) were random effects, while site, treatment, and year were fixed effects. For each analysis, statistical significance was based on a p value of <0.05.

Results and Discussion

Experiment 1: Differences in Chemical Composition of Switchgrass Cultivars

Biomass quality traits differed among cultivars (Table 3). Cave-in-Rock had the highest concentrations of aNDF and ADL, while Carthage had the lowest. Carthage had the highest concentration of N. Ash and NDFD48 did not differ among cultivars. Values for each constituent for Shawnee were consistently between those for Cave-in-Rock and Carthage. There were no cultivar × year interactions.

Our biomass compositional values are comparable to those cited in other literature. Cortese and Bonos [4] showed a significant year × cultivar effect for ash content across 2 years and ten cultivars. Similar to our findings, ash contents for Cave-in-Rock (6.0 %) and Carthage (6.4 %) did not differ, but our ash contents of 5.8 % were much higher than theirs at 2 %. Lemus et al. [19] showed average ash contents of 6.1 % across 20 cultivars in the Midwestern USA, very close to our ash contents that ranged from 5.3 to 6.3 %. Our data for switchgrass aNDF varied between 76.9 and 84.0 %, which is very similar to those of Lemus et al. [19] who showed a mean of 73.7 % across 20 cultivars grown in Iowa.

Experiment1: Cell Wall Constituents

Concentrations of GLC, GAL, GLCS, and FRU differed across cultivars (Table 4). As in biomass composition, cell wall constituent concentrations for Shawnee were intermediate between the other two cultivars. Cave-in-Rock had the highest values for GLC, which ranged from 31.7 % for Cave-in-Rock to 28.5 % for Carthage. The GLC values are very close to those reported by others. Adler et al. [1] showed different GLC concentrations over years for Cave-in-Rock at 28.6 and 32.5 %. Schmer et al. [29] reported averages of 27.6 % GLC for Cave-in-Rock and 20.6 % GLC for Shawnee, while Dien et al. [6] found a post-frost harvest GLC concentration of 32.2 % for Cave-in-Rock and 28.1 % for Shawnee. Carthage had the highest concentration for GAL with 0.93 %, while Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee had similar values of 0.83 %. GLCS was highest for Carthage and Shawnee at 1.6 %. Carthage showed the highest concentration of FRU (1.1 %), while Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee had similar values. Concentrations of GAL in 2012 of 0.93 % were higher than in 2013 when they were 0.80 %. Years also differed for STA concentrations of 0.16 and 0.42 % in 2012 and 2013, respectively. There were no cultivar × year interactions for any cell wall component.

The MAN, STA, SUC, XYL, and ARA concentrations were all similar among cultivars. Concentrations of MAN averaged 0.80 % and ranged from 0.94 % for Cave-in-Rock to 0.77 % for Carthage. Averaged over cultivars, MAN concentrations were higher at 0.91 % in 2012 than in 2013 with 0.78 %. In other studies, MAN concentration for Cave-in-Rock was found to be closer to 0.50 % with Adler et al. [1] reporting 0.59 % and Dien et al. [7] reporting 0.50 %. STA ranged from 0.18 to 0.43 %, SUC from 2.7 to 3.1 %, XYL from 20.6 to 22.2 %, and ARA from 2.8 to 2.9 %. Other studies reported XYL values for Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee within our range. For Cave-in-Rock, Adler et al. [1] showed an average XYL concentration of 22.2 % and Dien et al. [7] reported 22.3 %.

Experiment1: Theoretical Ethanol Yield and Production

Only ethanol yield from the hexose sugars (HEX and C6) differed among cultivars (Table 5) with Cave-in-Rock having higher values compared to Carthage, with Shawnee being intermediate. Only HEX differed among years with 2013 having a higher value at 271 L Mg−1 (Table 5).

Our TEY1 was similar among cultivars and ranged from 426 to 457 L Mg−1 with an average value of 437 L Mg−1 (Table 5). The TEY2 (using fewer constituent sugars) differed slightly among cultivars with Cave-in-Rock showing higher values at 425 L Mg−1. Schmer et al. [29] showed no differences between Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee for their TEY using method 1. Averaged over sites and years, they showed Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee yielded 420 and 425 L Mg−1, respectively, which are very close to those we reported.

The TEP1 and TEP2 differed among cultivars. Cave-in-Rock had the highest TEP1 with a value of 7350 L ha−1, while Carthage and Shawnee averaged 2930 L ha−1 (Table 5). Our values for Cave-in-Rock were much higher and Carthage and Shawnee were only slightly higher than the TEP values reported by Schmer et al. [29]. They did not find differences between the two cultivars, with Cave-in-Rock ranging from 2310 to 3286 L ha−1 and Shawnee ranging from 2032 to 2247 L ha−1 [29]. Keshwani and Cheng [16] reported that adapted switchgrass varieties should produce between 5000 to 6000 L of ethanol ha−1, higher than Schmer et al.’s [29] estimate of 2000 to 4000 L ha−1. These switchgrass TEP values contrast with 4000 L ha−1 for corn starch and 2000 L ha−1 for corn stover from agricultural soils [16].

The simpler equations used in method 2 to calculate TEY and TEP showed a similar trend, with TEY2 and TEP2 being 5 to 10 % less than TEY1 and TEP1 (Table 5). Cave-in-Rock was again higher in TEY2 using C6 and C5 and, with its higher biomass yield, provided almost double the TEP2 than the other two cultivars. Adler et al. [1] showed Cave-in-Rock producing an average of 427 L Mg−1 averaged over two fall season harvests using the method 2 equations. Using method 2, two upland varieties averaged over a 3-year period showed TEY2 for both Dacotah and Sunburst to be 350 L Mg−1 while TEP2 was approximately 3800 L ha−1for Dacotah and 5000 L ha−1 for Sunburst [23]. Our Cave-in-Rock and Shawnee grown at Hampshire would be considered “high yielding” by Schmer et al. [30] since both cultivars had TEP2 similar to or greater than 3800 L ha−1.

The main factor that influenced the higher TEP for Cave-in-Rock was its high biomass production compared to Shawnee and Carthage. At Hampshire, TEPs for Cave-in-Rock are much higher than values in the literature, which could be due to our methods for determining yields. Our yield estimates were based on clipped plots, where we carefully collected the biomass for determining dry weight. In conventional large-scale biomass harvesting, Adler et al. [1] showed that 21 % of biomass can be left behind. Assuming a similar loss of biomass, our aboveground biomass yields and TEPs would be reduced to values similar to those of other field studies.

Experiment 2: Differences in Switchgrass Chemical Composition due to Fertilizer Applications

For biomass composition, Cave-in-Rock switchgrass grown at Black Castle differed only for ADL concentrations compared to those at Coal Mac (Table 6). The effect of year differed for all biomass quality traits except NDFD48. In 2012, N and ash were higher, while in 2013, aNDF and ADL were higher. Composition of switchgrass is known to vary among years because of age and stand maturity, environmental differences, and harvesting times. Our biomass quality differences are probably more related to age and maturity of the switchgrass stand than to environmental causes. As switchgrass matures, lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose all increase. An increase in cell wall and lignin concentrations will decrease biomass digestibility. Additional studies over a longer time period could help separate effects of switchgrass stand age from environmental differences across years on biomass composition from these sites.

Across treatments, all traits except for NDFD48 differed, with higher fertilizer resulting in lower N and ash concentrations in biomass. The highest percentage of aNDF was for high fertilizer with low mulch treatment (HF:LM) at 78.3 %. Alamo switchgrass had 80.7 % aNDF averaged across three fertilizer treatments up to 90 kg N ha−1 [11].

For N concentrations, NF:LM was the highest at 0.57 % while the other three had lower values averaging 0.31 %. Interaction was due to the highest value for no fertilizer in 2012 but not for 2013. Our N concentration for NF:LM was much higher than 0.34 % reported by Sadeghpour et al. [28] for Cave-in-Rock grown with no fertilizer. Although our N application rates were at the low end of the range, our results did not show increasing biomass N concentration with increasing fertilizer rate as suggested by Lemus et al. [18]. Waramit et al. [36] did not show a fertilizer rate effect for N concentration of Cave-in-Rock over rates of 0, 65, and 140 kg N ha−1 and the biomass in their study averaged 0.6 % N concentration.

Ash levels were highest for NF:LM at 8.1 % and lowest with HF:LM at 5.7 %. These levels for Cave-in-Rock are higher than the average ash concentrations reported by Sadeghpour et al. [28] and Wilson et al. [37] of 3.6 and 4.5 %, respectively. Our ash concentrations are similar to those for Cave-in-Rock grown by Waramit et al. [36]. Over rates of 0 to 140 kg N ha−1, they showed similar concentrations of approximately 7.0 % in 2006 and 6.5 % in 2007. Values for ADL were lowest for NF:LM at 2.9 % which are lower than those reported by Waramit et al. [36] of 4.0 to 4.5 % over rates of 0 to 140 kg N ha−1.

Experiment 2: Cell Wall Constituents

A few ethanol prediction constituents differed among sites, years, and treatments (Table 7). The two sites were only different for STA and SUC. Sugars in biomass differed between years for GLC, STA, FRU, XYL, and ARA. No site × treatment interactions were found, while SUC and ARA were the only constituents with a treatment × year interaction. The only differences among treatments were for GLC, XYL, and ARA. Our values for XYL of 21.5 % are similar to those of Adler et al. [1] who reported concentrations in Cave-in-Rock to be 22.2 % averaged over two fall harvest seasons.

Experiment 2: Theoretical Ethanol Yield and Production

Ethanol prediction values did not differ between sites (Table 8). Because all sugars could not be predicted for biomass from these two sites, a simplified version of method 2 was used which only included GLC and XYL (method 3, Table 2). Years differed in ethanol prediction values, and 2013 was always greater than 2012. Since 2013 had greater biomass yields as well as TEY3, TEP3 was greater in 2013. Treatments differed for all ethanol prediction values and NF:LM had the lowest GL, XY and TEY3 and TEP3 values. Adler et al. [1] had a much higher ethanol yield of 427 L Mg−1 from Cave-in-Rock averaged over two fall harvests. They used an equation that also only used XYL to estimate pentose ethanol yield, but that equation included more constituents in the hexose calculation, which obviously contributed to higher ethanol yield. The HF:LM treatment had the greatest TEP3 at 1520 L ha−1 due to higher biomass yield.

Since a simplified equation (method 3) was used on these sites, theoretical ethanol yields from Black Castle and Coal Mac using TEY3 were obviously lower compared to Hampshire using TEY1 and other studies where more sugars were included in their calculations.

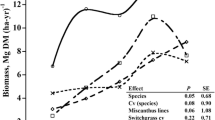

Schmer et al. [30] suggested a simple conversion of 380 L of ethanol Mg-1 of biomass can be used to predict TEP. From Hampshire, the TEY1 data gave values of 427 to 457 L Mg−1, which are higher that this estimate of 380. To compare this simple conversion to our results, TEP1 for Cave-in-Rock at Hampshire was 7350 L ha−1 (Table 5). Using the 380 L Mg—1 conversion and a biomass yield of 16 Mg ha−1 (Cave-in-Rock yield at Hampshire from Fig. 2 in Brown et al. [3]), TEP was calculated to be 6080 L ha−1, which is lower than both TEP estimates by methods 1 and 2 (Table 5).

Conclusion

In spite of few to no differences among cultivars for TEY at Hampshire, Cave-in-Rock had significantly higher TEP due to its higher biomass production compared to Shawnee and Carthage. Fertilizing switchgrass at planting increased TEY and TEP, which was due to slight increases in GLY and XYL and to primarily greater biomass production. In comparing our results to other studies, switchgrass biomass quality and composition grown on surface mines is similar to that grown on agricultural soils, and TEYs are within the range of other studies in the USA. Six years after seeding, TEP1 at Hampshire with Cave-in-Rock was over 7000 L ha−1, which is greater than estimates of 4000 to 5000 L ha−1 for other sites in the USA.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

Dry matter

- EC:

-

Electrical conductivity

- NIRS:

-

Near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy

- TEP:

-

Total ethanol production

- TEY:

-

Total ethanol yield

References

Adler PR, Sanderson MA, Boateng AA, Weimer PJ, Jung H-JG (2006) Biomass yield and biofuel quality of switchgrass harvested in fall or spring. Agron J 98:1518–1525

Adler PR, Sanderson MA, Weimer PJ, Vogel KP (2009) Plant species composition and biofuel yields of conservation grasslands. Ecol Appl 19:2202–2209

Brown C, Griggs T, Skousen J (2015) Switchgrass yield and quality on reclaimed surface mines in West Virginia. Bioenerg Res (this issue)

Cortese LM, Bonos SA (2013) Bioenergy traits of ten switchgrass population grown in the Northeastern/Mid-Atlantic USA. Bioenerg Res 6:580–590

David K, Ragauskas AJ (2010) Switchgrass as an energy crop for biofuel production: a review of its ligno-cellulosic chemical properties. Energy Environ Sci 3:1182–1190

Dien BS (2010) Mass balances and analytical methods for biomass pretreatment experiments. P. 213-231. In: Vertes AA, Qureshi N, Blaschek HP, Yukawa H (eds) Biomass to biofuels: strategies for global industries. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford. doi:10.1002/9780470750025

Dien BS, Jung HG, Vogel KP, Casler MD, Lamb JS, Iten L, Mitchell RB, Sarath G (2006) Chemical composition and response to dilute-acid pretreatment and enzymatic saccharification of alfalfa, reed canarygrass, and switchgrass. Biomass Bioenergy 30:880–891

Dwivedi P, Alavalapati JR, Lal P (2009) Cellulosic ethanol production in the United States: conversion technologies, current production status, economics, and emerging developments. Energy Sustain Dev 13:174–182

Fahmi R, Bridgwater AV, Darvell LI, Jones JM, Yates N, Thain S, Donnison IS (2007) The effect of alkali metals on combustion and pyrolysis of Lolium and Festuca grasses, switchgrass and willow. Fuel 86:1560–1569

Gray KA, Zhao L, Emptage M (2006) Bioethanol. Curr Opin Chem Biol 10:141–146

Guretzky JA, Biermacher JT, Cook BJ, Kering MK, Mosali J (2011) Switchgrass for forage and bioenergy: harvest and nitrogen rate effects on biomass yields and nutrient composition. Plant Soil 339:69–81

Hames BR (2009) Biomass compositional analysis for energy applications. In: Mielenz JR (ed) Biofuels, methods in molecular biology Vol. 581, Humana Press, p. 145-167

Hu Z, Sykes R, Davis MF, Brummer EC, Ragauskas AJ (2010) Chemical profiles of switchgrass. Bioresour Technol 101:3253–3257

Jarchow ME, Liebman M, Rawat V, Anex RP (2012) Functional group and fertilization affect the composition and bioenergy yields of prairie plants. Glob Change Biol Bioenergy 4:671–679

Jiang Y, Yuan Y, Wang Y (2012) Physiological response, cell wall components, and gene expression of switchgrass under short-term drought stress and recovery. Crop Sci 52:2718–2727

Keshwani D, Cheng JJ (2009) Switchgrass for bioethanol and other value-added applications: a review. Bioresour Technol 100:1515–1523

Lamb JFS, Jung HG, Riday H (2014) Growth environment, harvest management and germplasm impacts on potential ethanol and crude protein yield in alfalfa. Biomass Bioenerg 63:114–125

Lemus R, Brummer EC, Burras CL, Moore KJ, Barker MF, Molstad NE (2008) Effect of nitrogen fertilization on biomass yield and quality in large fields on established switchgrass in southern Iowa, USA. Biomass Bioenerg 32:1187–1194

Lemus R, Brummer EC, Moore KJ, Molstad NE, Burras CL, Barker MF (2002) Biomass yield and quality of 20 switchgrass populations in southern Iowa, USA. Biomass Bioenerg 23:433–442

Liu L, Ye XP, Womac AR, Sokhansanj S (2010) Variability of biomass chemical composition and rapid analysis using FT-NIR techniques. Carbohydr Polym 81:820–829

Lorenz AJ, Coors JG, de Leon N, Wolfrum EJ, Hames BR, Sluiter AD, Weimer PJ (2009) Characterization, genetic variation, and combining ability of maize traits relevant to the production of cellulosic ethanol. Crop Sci 49:85–98

Lorenzana RE, Lewis MF, Jung HG, Bernardo R (2010) Quantitative trait loci and trait correlations for maize stover cell wall composition and glucose release for cellulosic ethanol. Crop Sci 50:541–555

Monono EM, Nyren PE, Berti MT, Pryor SW (2013) Variability in biomass yield, composition, and ethanol potential of individual and mixed herbaceous biomass species grown in North Dakota. Ind Crop Prod 41:331–339

NIRS Forage and Feed Testing Consortium (2014) NIRSC calibrations. http://nirsconsortium.org/. Accessed 23 Dec 2014

National Renewable Energy Laboratory (2014) Standard Procedures for Biomass Compositional Analysis. [Online]. http://www.nrel.gov/biomass/analytical_procedures.html. Accessed 8 Aug 2014

Peters J (ed) (2013) Wisconsin procedures for soil testing, plant analysis and feed & forage analysis. University of Wisconsin-Madison Soil Testing Laboratories, http://uwlab.soils.wisc.edu/lab-procedures. Accessed 18 Dec 2014

Sanderson MA, Agblevor F, Collins M, Johnson DK (1996) Compositional analysis of biomass feedstocks by near infrared reflectance spectroscopy. Biomass Bioenerg 11:365–370

Sadeghpour A, Gorlitsky LE, Hashemi M, Weis SA, Herbert SJ (2014) Response of switchgrass yield and quality to harvest season and nitrogen fertilizer. Agron J 106:290–296

Schmer MR, Vogel KP, Mitchell RB, Dien BS, Jung HG, Casler MD (2012) Temporal and spatial variation in switchgrass biomass composition and theoretical ethanol yield. Agron J 104:54–64

Schmer MR, Vogel KP, Mitchell RB, Perrin PK (2008) Net energy of cellulosic ethanol from switchgrass. Proc Natl Acad Sci 105:464–469

Shapiro SS, Wilk MB (1965) An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52:591–611

Shenk JS, Westerhaus MO (1991) Population structuring of near infrared spectra and modified partial least squares regression. Crop Sci 31:1548–1555

Statistical Analysis S (2011) SAS/STAT systems for windows v.9.3. SAS Institute, Cary

Tsuchikawa S (2007) Sampling techniques. In: Ozaki Y, McClure WF, Christy AA (eds) Near-infrared spectroscopy in food science and technology. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, pp 133–144

Vogel KP, Dien BS, Jung HG, Casler MD, Masterson SD, Mitchell RB (2011) Quantifying actual and theoretical ethanol yields for switchgrass strains using NIRS analyses. Bioenerg Res 4:96–110

Waramit N, Moore KJ, Heggenstaller AH (2011) Composition of native warm-season grasses for bioenergy production in response to nitrogen fertilization rate and harvest date. Agron J 103:655–661

Wilson DM, Dalluge LD, Rover M, Heaton EA, Brown RC (2013) Crop management impacts biofuel quality: influence of switchgrass harvest time on yield, nitrogen and ash of fast pyrolysis products. Bioresour Technol 6:103–113

Wolfrum EJ, Sluiter AD (2009) Improved multivariate calibration models for corn stover feedstock and dilute-acid pretreated corn stover. Cellulose 16:567–576

Yan J, Hu Z, Pu Y, Brummer EC, Ragauskas AJ (2010) Chemical compositions of four switchgrass populations. Biomass Bioenerg 34:48–53

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, the NEWBioNortheast Woody/Warm-season Grass Biomass Consortium, and with funds appropriated under the Hatch Act at West Virginia University. Scientific article #3254 from the West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. The authors thank Rick Herd, Brady Gutta, Paul Ziemkiewicz, Ken Ellison, Scott Schumaker, Rodney Mangold, John McHale, Rick Adams, Terry Potter, Kermit Fincham, David McMichael, and Marcus McCartney for help with project development, site access, and analysis during the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, C., Griggs, T., Holaskova, I. et al. Switchgrass Biofuel Production on Reclaimed Surface Mines: II. Feedstock Quality and Theoretical Ethanol Production. Bioenerg. Res. 9, 40–49 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-015-9657-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-015-9657-3