Abstract

Efficient conversion of lignocellulosic feedstocks to ethanol will benefit from a consistent composition of supplied biomass. While composition or quality for a given feedstock is known to vary, the influence of environment, rather than genotype, has rarely been separated for mature field-grown material. Replicated trials of a single sterile hybrid clone of Miscanthus × giganteus across Illinois provided a unique opportunity to test the influence of environmental, rather than genetic control over biomass composition, under US Midwest conditions. Given the interest in M. x giganteus cv. “Illinois” as a lignocellulosic feedstock, it is valuable to understand the variation in composition of this crop that would need to be dealt with by processors. This study examined the effect of seven sites spanning nearly 5° in latitude and contrasting soil types from sands to clays with land capability classes ranging from 1 to 4. Four levels of nitrogen fertilization (0, 67, 135, and 202 kg N ha−1) were applied on these mature, genetically identical, clonally propagated stands of M. × giganteus which were harvested both pre- and post-senescence. Despite the wide range of environmental differences, there was minimal variation in the composition across all locations, sampling times, and fertilization treatments. Composition varied from 39–45 % for cellulose, 19–24 % for hemicellulose, to 19–24 % for lignin. Nitrogen fertilization, while having a small effect, decreased the proportion of hemicellulose, acetyl groups, and ash and increased cellulose and lignin at statistically significant levels. Delaying harvest from October to December increased the proportion of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin and decreased the proportion of ash and extractables at statistically significant levels. The findings show that in the absence of genetic variation, composition varies minimally with environment or timing of harvest, which has important implications for costs of processing in a given location.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lignocellulosic biofuel production requires the efficient digestion of large quantities of feedstock. The C4 warm season perennial grasses Miscanthus × giganteus Greef and Deuter ex Hodkinson and Renvoize [22, 35] is a high-yielding, low-input lignocellulosic bioenergy feedstock which has been grown for many years without fertilization and with limited weed control [11, 2, 3, 47]. The material of this species has become known in the USA as the Illinois clone [20] and has proved particularly productive in the Midwest USA [2, 3, 27]. This is to the extent that by 2012, the US Department of Agriculture Biomass Crop Assistance Program, which assists owners and operators in the development of commercial biomass operations, stipulated this clone of Miscanthus as the sole feedstock for 4 of its 11 Project Areas [19]. Lignocellulose is composed largely of three primary cell wall polymers: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [21, 51]. The relative proportion of these carbohydrates in a feedstock is known to vary significantly and influences ease of conversion to monosaccharides and disaccharides for fermentation and in turn ethanol yield [50, 55, 56, 36]. A constant composition also avoids the need to vary amounts of acid, enzyme, other chemicals, and physical conditions to optimize deconstruction. If the biomass is used for pyrolysis, then the resulting “oil” and optimum temperatures and flows in processing are also affected by feedstock biochemical composition [13, 48, 18]. Consistency in the composition of the harvested biomass is therefore a key factor in realizing economic cellulosic fuels, whether via biochemical or thermochemical routes [21, 31, 14].

With present technologies for biochemical biofuel production, the content of lignin is seen as the major barrier. Lignin is not easily separated from cellulose, impeding separation of cellulose fibrils and slowing access by cellulases. Biomass has to be pretreated in order to make the polysaccharides more accessible to enzymes. A common pretreatment step involves heating biomass in the presence of dilute sulfuric acid. Degradation products formed during this process can inhibit the growth of microorganisms and therefore inhibit fermentation of sugars into biofuels. Lignin can also irreversibly bind enzymes and inhibit the enzymatic de-polymerization of cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars. In theory, the lower the lignin content in biomass, the better. However, lignin is a cross-linked polymer that is essential in providing structural support, limiting pest damage, and allowing xylem vessels to function under the high tensions that develop during transpiration [21, 25, 43].

Hemicellulose, a heteropolysaccharide composed mainly of C5 sugar residues, is more easily converted to sugars than cellulose, a homopolymer of β-1,4-linked glucose units primarily in crystalline microfibril form [50]. Yeasts have been engineered which can efficiently ferment the C5 sugar xylose with the penultimate product of cellulose degradation, the disaccharide cellobiose [23, 37]. Overall, feedstock composition affects process configurations, reactor designs, and process performance [55]. Variation in feedstock composition would therefore affect processing efficiency since built capacities for different parts of the processing, such as pretreatment, depolymerization, C5 fermentation, and C6 fermentation, can only be optimal for a single feedstock composition.

The hemicelluloses of the cell wall have varying degrees of acetylation [10]. Pretreatment of bioenergy feedstocks therefore results in the release of acetate, which is a partial inhibitor subsequent enzymic saccharification and microbial fermentation [10]. Therefore, it is desirable that acetyl concentration in bioenergy feedstocks is as low as possible. At the time of writing, no studies had been published that examine changes in acetyl contents, which can substantially affect enzymic processing to biofuels.

Inorganic elements such as potassium, phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium in the harvested biomass constitute its ash content after conversion or combustion [52]. Ash is a waste product which can cause slagging in direct combustion and inhibit enzymatic conversion, but in pyrolysis, it can also lead to the valuable co-product biochar [52]. Silica is the largest component of ash affects the use of biomass in combustion and lowers efficiency of production of cellulosic biofuels [4, 8]. Therefore, as a general rule, the lower the ash content, the better the quality for most end uses.

Non-structural, solvent-soluble, and non-volatile compounds make up the extractable component of biomass, which is predominantly leaf and stem cuticle waxes [52]. Extractables including fatty acids, starch, resins, chlorophylls, and waxes are typically a minor fraction of total biomass composition, but could comprise a potential source of value-added co-products in large-scale lignocellulosic operations [52] but can also include inhibitors of saccharification of cellulose and hemicellulose and of fermentation of the resulting sugars. It is therefore important to know the concentration of extractables and how environment affects this component.

Large differences between genotypes of individual feedstocks have been shown with more than 20 % variation in lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose contents [7, 52, 57]. Although much emphasis has been placed on genetic drivers for cell wall composition [21], less emphasis has been given to understanding variation induced by environmental variation, including differences in agronomy. Harvest time and location were recently found to be key drivers of cell wall composition of Zea mays (maize) stover [56]. Understanding temporal and spatial variation in feedstock quality in terms of composition will be critical to the performance of lignocellulosic fuel manufacturing facilities. It may also indicate cultural practices, harvest times, soil type, or climates that may favor a higher quality biomass with respect to ease of conversion to biofuels or bioenergy. Since stands of the rhizome-propagated sterile hybrid M. × giganteus Illinois have been cloned to date from a single hybridization event and therefore lack genetic variation, this species and single clone serves as a unique opportunity to study variation in cell wall components caused solely by environmental factors. Furthermore, given the emergence of M. × giganteus as a lignocellulosic feedstock, it is important to understand its composition and the factors causing it to vary in designing processing facilities.

Previous studies in W. Europe have examined changes in cell wall composition of M. × giganteus in response to different fertilizer treatments over the growing season at one location [32], differences between different M. × giganteus clones at multiple locations [33], and cultivars of Miscanthus spp. at one location [34, 44]. With more mild winters, harvest dates in W. Europe are often later and so composition may be examined in January through March compared to autumn harvests in the Midwest USA [2, 46]. Although these studies provided important information on variation with site and genotype, they did not specifically separate out the effects of location combined with variation in nitrogen fertilization level on M. × giganteus. Other studies have shown a trend of increasing lignin and cellulose with delayed harvest, but no pattern has emerged for hemicellulose (Table 1). Hodgson et al. [32] showed that with increasing nitrogen fertilization, there was a decrease in the cell wall components’ cellulose and hemicellulose in the stem and a decrease in the proportion of cellulose in the leaf material; however, this was only tested at 0 and 50 kg N ha−1. Lemus et al. [38] examined changes in biomass quality in another perennial grass, Panicum virgatum, across four nitrogen treatment rates (0, 56, 112, and 224 kg N ha−1) and determined that cellulose and lignin increased with increased rate of nitrogen fertilization, while hemicellulose and ash declined in bulk biomass material. Soil fertility, nitrogen status, and temperature might all be expected to cause significant phenotypic variation in cell wall composition. Further, the first replicated field trials of M. × giganteus in the Midwestern USA have shown much higher autumn and winter yields than typically observed in Europe; it might therefore be expected that quality, as well as quantity, will be affected by this very different growth environment [2, 27]. Also, and in contrast to the findings of most European studies, a split-plot nitrogen fertilization experiment demonstrated that yield of mature stands of M. × giganteus was significantly increased by nitrogen fertilization from 23.4 Mg ha−1 at 0 kg(N)ha−1 to 28.9 Mg ha−1 at 202 kg(N)ha−1 (+25 %) [3].

Three fully replicated trials were established in 2002 in the Midwestern USA [27], and four further sites were established in 2004 [2]. Starting in 2007, four levels of nitrogen fertilization were added to these established plots using a split-plot design [3]. These seven mature stands of M. × giganteus in the Midwestern USA, all of similar age, provided a unique opportunity to isolate the effect of location, nitrogen, and harvest time on the quality of harvested feedstock in terms of cell wall components.

Given this unique opportunity, the hypothesis that soil type, nitrogen fertilization, and harvest time will affect cell wall composition, independent of genotype, was tested. This was achieved by quantifying cellulose (as glucan), hemicellulose (as xylan and arabinan), lignin (Klason lignin), acetyl, ash (total ash before extraction), and extractable biomass components at these seven locations, across four nitrogen fertilizer levels, and at two harvest dates on genetically identical clonally propagated and replicated stands of M. × giganteus.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Biomass samples were collected in 2009 from trials of M. × giganteus established at seven sites spanning a variety of soil and weather conditions within Illinois (Supplementary Table 1, Fig. 1). Planted in 2002, the three field trials included in this study are the oldest replicated research trials of M. × giganteus in the USA and are located in DeKalb (88.15 W, 41.85 N) and Urbana (88.23 W, 40.08 N), Dixon Springs (88.67 W, 37.45 N), Illinois; establishment and maintenance of these trials have been previously described by Heaton et al. [27] and Arundale et al. [2]. Four additional field sites were established in 2004 following the same procedures and experimental design in Havana (89.84 W, 40.30 N), Orr (90.82 W, 39.81 N), Brownstown (88.96 W, 38.95 N), and Fairfield (88.39 W, 38.38 N), Illinois. Briefly, these field trials were established in a completely randomized design with plots measuring 10 m × 10 m (n = 4) planted with rhizome-propagated M. × giganteus stock of the genotype which has become known as the Illinois clone [20, 19]. Trials were established from greenhouse-grown potted plants planted on 1-m centers. A split-plot N fertility treatment was initiated in DeKalb and Dixon Springs in 2007 and at the remaining five sites in 2008 [3]. Briefly, each whole 10 m × 10 m M. × giganteus plot was sub-divided into four 5 m × 5 m sub-plots that were randomly assigned a nitrogen treatment of 0, 67, 134, or 202 kg N ha−1. Nitrogen was applied in the form of either granular ammonium nitrate (34 % N; Dixon Springs and DeKalb) or granular ammonium sulfate (21 % N; all other locations) in the spring, as described previously [3]. In summary, the design was four whole plots at each site, with each of these whole plots that was split into 5 m × 5 m sub-plots representing the four nitrogen rates.

Cumulative annual (Jan 1–Dec 31) GDD base 10 °C (GDD10) (filled circle) and Palmer Hydrological Drought Index (PHDI) (inverted triangle) in 2009 from seven monitoring stations of the Midwestern Regional Climate Center (http://mrcc.isws.illinois.edu) near field stations planted in 2002 located at a) DeKalb, b) Urbana, c) Dixon Springs, and planted in 2004 d) Havana, e) Orr, f) Brownstown, and g) Fairfield. Solid line indicates “0” value of PHDI

In 2009, 5–7 years after planting, above-ground biomass samples were collected from all seven locations prior to senescence on October 23–26 and again after completion of senescence and dry-down of the crop on December 4–7. Sampling followed the methods outlined by Heaton et al. [27]. Briefly, all standing biomass (i.e., stems and leaves) were harvested as a bulk biomass subsample from a quadrat of 0.19 m2 to a 5-cm stubble height in each treatment sub-plot (i.e., 5 by 5 meter nitrogen sub-plot within each M. × giganteus whole plot). This was to mimic commercial harvesting which is based on hay cutting and harvesting which could not separate dead stem and leaf material [58]. Hence, analysis of the resulting bulk material as would be provided to a processing facility. There were four independent biological replications for each nitrogen treatment at each location (n = 4). Samples were dried to constant mass at 74 °C. Dry tissue was then ground in a cutting mill (Cutting Mill SM 200, Retsch, Inc., Haan, Germany) fitted with a 2-mm sieve. From each biological replicate, approximately 50 g of ground material was subsampled for compositional analysis.

Growing Conditions

Soil descriptions, previous cropping history, and previous plot maintenance were described previously ([2, 17, 27], Supplemental Table 1). Weather data were obtained from NOAA’s Midwestern Regional Climate Center’s Applied Climate System (http://mrcc.isws.illinois.edu; Fig. 1) and reported from the nearest weather station to each field trial. These were all within 1 km, except for Dixon Springs, where the nearest weather station with data for >90 % of the relevant period covered was 34 km away (Supplementary Table 2). The Palmer Hydrological Drought Index (PHDI) provides an integrated measure of water availability reflecting soil moisture throughout the entire year [30, 49] and is therefore more closely related to crop growth than precipitation. This measure ranges from −6 for the driest conditions to +6 for the wettest, with 0 as optimal for crop growth in a given climate zone. It is reported for most crop-producing areas of the USA [49] and so was readily available for each site. The PHDI was therefore used in this study to account for variation in moisture availability between sites in the given year. Growing degree days provide an integration of heat sufficient to support crop production (GDD1); this was calculated for each site as:

where T avg is mean daily temperature and GDD10 is 0 on days where T avg ≤ 10 °C.

Compositional Analysis

Seven locations with four whole plots per location and four nitrogen sub-plots per whole plot and sampled on the two dates given above resulted in the 224 biomass samples analyzed. From each biomass sample, a subsample of 50 g was taken to provide material for two technical replicates, giving a total of 448 measurements. Compositional analysis was performed via wet chemistry following the methods described by Sluiter et al. [53] and Haffner et al. [24].

M. × giganteus was ground using a high-speed rotor mill (Ultra Centrifugal Mill ZM 200, Retsch) passing a 2-mm sieve and then oven-dried. In an extraction cell, 1 g of biomass and a preweighed microfiber filter (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were extracted with water and ethanol in an accelerated solvent extractor (ASE350, Dionex). The extraction conditions were 100 °C temperature, 5 min holding time, 3 cycles per solvent, and a 60-s nitrogen purge. The biomass after removal of soluble components was transferred into preweighed aluminum pans and dried and cooled in a desiccator. The difference of starting mass and mass after extraction provided the mass of extractables, i.e., that dissolved by the solvent.

The remaining biomass was pulverized in a canister ball-mill (model 8200 tissue pulverizer, Kinetic Laboratory Equipment Company, Visalia, CA, USA) and oven-dried. Fifty milligram was incubated at room temperature with 0.5 cm3 of 72 % (w/w) sulfuric acid in a modified Hungate vial capped with a rubber stopper; the mixture was vortexed every 15 min. After 1 h, deionized water was added, and the mixture was autoclaved for 60 min. A sugar recovery standard containing glucose, xylose, and arabinose with the same sulfuric acid concentration was prepared in parallel and co-autoclaved with the samples. After cooling to room temperature, the suspension was vigorously shaken, kept at 4 °C for 12 h to precipitate the solids. Two cubic centimeters of the clear supernatant was then removed and filtered and used for HPLC analysis.

The precipitated solids were re-suspended by vortexing, and the suspension was filtered through a glass microfilter. Both the vial and filter were repeatedly rinsed with deionized water and then dried; the residual mass (m1) was determined after cooling in a desiccator. The filter and solids were then heated to 575 °C, and the residual mass or ash (m2) was determined after cooling in a desiccator for 30 min. The difference m1 − m2 represented the amount of Klason lignin corrected for ash content.

Cellulose (as glucan), hemicellulose (as xylan and arabinan), and acetyl contents were determined at 50 °C by HPLC on an organic acid separation column (Aminex HPX-87H, 300 × 7.8 mm, Bio Rad, Richmond, CA on a 1200 series HPLC) with a refractive index detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Elution was performed with 0.005 M sulfuric acid at a flow rate of 0.6 cm3 min−1. For calibration, solutions of reference compounds in the range of 0.01−10 mg were prepared.

Calculation of Theoretical Ethanol Production

The US Department of Energy, Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy “Theoretical Ethanol Yield Calculator” [15] was used to calculate theoretical ethanol production based on measured glucan, xylan, and arabinan concentrations of the biomass samples. The theoretical ethanol conversion factor was calculated as:

The product of the theoretical ethanol conversion factor (l Mg−1) and biomass yield (Mg ha−1) gives the overall ethanol yield per unit land area.

Statistical Analysis

The mean value of the two technical replications of each biological replication was treated as a single experimental sample for statistical analysis (n = 4). Each factor was evaluated individually via split-plot mixed model analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the SAS statistical software package (PROC MIXED, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA [42]). That is, a separate analysis was performed for each of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, H/L, acetyl, ash, total extractables, ethanol conversion factor, biomass yield, and ethanol yield, each in turn represented as y. Location (L) and harvest month (M) were considered categorical fixed effects and nitrogen treatment (N), a continuous fixed effect, while plot effect at each location was considered random, as follows.

-

Model I:

$$ y=L+M+N+L\ast M+L\ast N+M\ast N+L\ast M\ast N+L(P) $$

Given the relatively small sample size and given that this experiment was performed only over 1 year, statistical significance is reported at α < 0.1 to minimize type II errors, i.e., risk of accepting the null hypothesis when it is in fact false. In all displayed figures, arithmetic means with 1 standard error of the mean are shown.

Results

Site Conditions

Relative to the average, 2009 was a wet and cool year for Illinois [1]. It was the 11th coolest and 8th wettest summer in Illinois since weather records began in 1895 [1]. However, the Annual Palmer hydrological drought index (PHDI), a measure of drought impact on crops, ranged from −4 in DeKalb at the northern end of Illinois to 2 in Dixon Springs at the southern end, while growing degree days (GDD10) ranged from 4000 to 4800 across the seven sites, representing very considerable variation, 20 % variation in heat and 30 % in available moisture between sites (Fig. 1).

Cell Wall Composition

Although many statistically significant differences were detected, their magnitude is small due to the low variance. Response to nitrogen was location dependent for lignin, extractables, H/L, and ethanol yield (Table 1). While this interaction was statistically significant, Table 2 shows the very small magnitude of the effects due to this interaction. Nitrogen fertilization led to statistically significant variation in the proportion of all components except extractables (Tables 1 and 2). However, all changes were small and almost all were under 2 % (Tables 1 and 2). When pooled across locations, increasing the nitrogen fertilization rate decreased the proportion of acetyl, ash, hemicellulose, and theoretical ethanol conversion factor and increased lignin, biomass, and theoretical ethanol yield (Table 2). Response to nitrogen was also dependent on harvest month for the theoretical ethanol conversion factor and proportions of acetyl and ash (Tables 1 and 2).

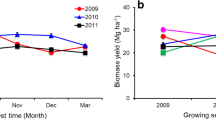

Harvest date had the largest individual impact on composition, as indicated by the higher F values (Table 1, Fig. 2). However, the overall changes while significant were again small. Between October and December changes, these were just +3 % in cellulose, +1.5 % in lignin, with decreases in hemicellulose, and a halving of ash and extractable contents (Table 2, Fig. 2). There was a statistically significant interaction of time of harvest with location for hemicellulose, ash, acetyl, and extractables and a statistically significant interaction of time of harvest with nitrogen treatment for ash and acetyl contents (Table 1, Fig. 2). Location had a small, yet statistically significant, impact on the proportion of lignin, cellulose (glucan), total hemicellulose (xylan + arabinan), hollocellulose/lignin ratio (H:L), acetyl, ash, and extractables, as well as the ethanol conversion factor, biomass yield, and overall ethanol yield (Table 1).

Changes in proportion (% of total mass) of extractables ( ), acetyl (

), acetyl ( ), ash (

), ash ( ), lignin (

), lignin ( ), hemicellulose (

), hemicellulose ( ), and cellulose (

), and cellulose ( ) by month of harvest (October and December) in unfertilized Miscanthus × giganteus pooled across seven locations in Illinois in 2009. Arrows indicate direction of change in concentration of component from October to December. Double asterisks significant difference between months at α < 0.05. Dagger significant interaction effect of month of harvest with location. Double dagger significant interaction effect of month of harvest with nitrogen fertilization rate

) by month of harvest (October and December) in unfertilized Miscanthus × giganteus pooled across seven locations in Illinois in 2009. Arrows indicate direction of change in concentration of component from October to December. Double asterisks significant difference between months at α < 0.05. Dagger significant interaction effect of month of harvest with location. Double dagger significant interaction effect of month of harvest with nitrogen fertilization rate

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if there would be variation in the composition of biomass fed to a processing plant from the same genotype grown at different locations, with different soils, weather, nitrogen fertilization levels, and dates of harvest within a supply region. The findings suggest surprisingly little variation, indicating with respect to genotype–environment interactions (G × E); the environmental component is very small. These trials used a single, but very widely used, clone of M. × giganteus. Nitrogen fertilization rate, time of harvest, and location led to statistically significant, but very small, changes in cell wall composition. Based on the measured cellulose and hemicellulose content, it was possible to calculate variation in the potential ethanol yield. However, when this chemical conversion factor is considered in conjunction with overall biomass yield (tDMha−1), it is clear that the influence of nitrogen application rate, time of harvest, and location on ethanol yield is predominantly through the effect on the quantity of biomass produced with very little effect on quality.

The lack of change in the proportion of hemicellulose with autumn versus winter harvest in the present study is in disagreement with previous studies which reported a decline in hemicellulose ([32–34]; Table 3). This apparent disagreement regarding changes in hemicellulose content is likely driven by differences in the proportion of leaf loss in this timeframe and earlier dates of harvest necessitated by climatic conditions in the US Midwest. The present study simulated mechanical harvesting with a hay cutter set at about 5 cm to avoid collecting any surface litter which may be contaminated with soil, as recommended to US growers [58]. This method at farm level could not practically separate stems and leaves, and our analysis was limited to the bulk that would be collected regardless of the proportion of stems and leaves. The observed increase in cellulose and lignin concentrations from October to December parallels previous findings ([26, 32–34], Table 1). The major change from October to December was an approximate halving of contents of extractables and ash (Fig. 2). This is most likely due to leaf drop and, therefore, a smaller proportion of the harvested mass being leaf material [28, 26]. Cuticle waxes are the major component of extractables, and with a much larger surface area to total mass, cuticle waxes are a larger proportion of the mass of leaves. Leaves similarly have higher ash content [7]. Decreases in inorganic content from October to December agree with the results of previous trials that found decreases in ash throughout the growing season [26, 34, 41]. The decline observed here in the autumn could result from re-translocation and from physical leaching of soluble ash components, as well as a decreased proportion of leaves in the harvested material [6, 28, 54]. These results furthermore suggest that a later harvest would result in yet further reductions in ash content. Current agronomic advice in Europe is to delay biomass harvest until late winter or early spring in order to reduce concentrations of K, Cl, S, N, and P which can negatively impact combustion of the feedstock [39, 40]. However, under US Midwest conditions, large losses in harvestable biomass occur in the winter, which were not apparent under western European conditions. This might be explained by fragmentation of the standing biomass under harsher freezing conditions [5, 6, 28]).

Location had a strong statistical effect, but small absolute effect, on overall cell wall composition (Table 1). Given that harvest occurred following the seventh growing season at three of the locations and following the fifth growing season at the remaining four locations, one aspect that could be driving location-dependent changes is stand age. However, no differences in composition were apparent between stands in their fifth and seventh year. Previous studies in Europe have similarly shown that cell wall composition is little affected by growing seasons or age of stand [34]. Harvest method also affects end-use value [46]. Only one harvest method was used here, and as explained earlier, this was designed to mimic the cutting of the whole stem, as in hay collection, which is the method used predominantly in the USA [29, 58].

Effects of location are more likely to be due to differences in baseline soil fertility, as well as precipitation and temperature patterns (Fig. 1). The lignin content of material from the driest site, Fairfield, was less than 1 % more than the wettest site, DeKalb (Table 2). Other site factors similarly appeared to have little effect (Table 2). Nitrogen fertilization had remarkably little effect on cell wall constituents; neither lignin, cellulose, nor hemicellulose showed a more than 1 % variation between the four treatments within either of the two harvest dates (Table 2). The average increase in lignin content with increasing N-fertilization rate was 0.75 %. Despite this small change, the low variance meant that this was a statistically significant increase. Similarly, acetyl and ash contents showed a significant decrease with increased nitrogen fertilization rate, but again, the changes were very small. When comparing locations to each other, the location with the highest land capability class, Urbana, which is a class “1” soil ([59, 60] Supplementary Table 2) and by definition is well-supplied with plant nutrients, showed the highest concentrations of lignin and the lowest concentrations of hemicellulose relative to the other locations (Table 2). However, DeKalb, which is a land capability class “2w” soil and has only minor limitations as compared to Havana (4 s) or Orr (3e, Supplementary Table 2), showed the lowest observed concentrations of lignin. This suggests that it is not only nitrogen availability which is driving these small differences.

The ethanol conversion factor is calculated as a theoretical maximum and does not take into account the inhibitory effects of lignin, ash, and acetyl, nor does it include possible additional ethanol produced from non-structural carbohydrates in the extractables which may also include precursors for value-added co-products. Specifically, lignin contributes to the recalcitrance of a feedstock and increasing lignin concentrations increase the cost of conversion of cellulose and hemicellulose by reducing the efficiency of the process [9]. The (cellulose + hemicellulose)/lignin ratio across locations ranged significantly from 2.88 (±0.03) to 3.32 (±0.04), a 15 % change, in unfertilized plots harvested in December. This ratio was seen to decline with increasing nitrogen fertilization rates, suggesting that as nitrogen fertilization increases, it will likely become more difficult to digest the feedstock (Tables 1 and 2), so while nitrogen fertilization increased biomass yield, this may be slightly offset by the small decline in quality with respect to ethanol production. Likewise, while yield was greater at the December harvest, this was partially offset by a decline in quality with respect to ethanol production. Biomass harvested in October has a 2.5 % higher (cellulose + hemicellulose)/lignin ratio 3.22 (±0.03) than biomass harvested in December 3.14 (±0.04). However, biomass harvested in October would be of a higher percent moisture and nitrogen concentration than when harvested in December [28], which would need to be adjusted for in the conversion process. An October harvest may also affect nitrogen use since the N offtake at this time of year is very much higher than in December [28, 16]. Moisture content was not considered in the present study since it was highly dependent on the conditions on the day of collection and would not provide a realistic average for the two harvest periods. The ethanol conversion factor does not take account of the adverse effect of ash content [8]. Ash content was halved by the later harvest which could offset the effect of the increased lignin content (Fig. 2).

In total, this study analyzed the chemical composition of almost 500 samples of a single genotype grown at seven contrasting sites under four nitrogen treatments and on two harvest dates. The results are most notable for showing that while environment strongly affects the quantity of biomass, it has little numerical effect on quality. This is a positive finding from the viewpoint of processing to biofuels or use in combustion. Large changes in feedstock composition would, for example, in the case of cellulosic ethanol production, require continual modifications to processing operations such as resetting of flows, adjustment of pretreatment conditions, and quantities of digestion enzymes. Any necessary changes would cause not only increased operational complexity but would also drive increased capital costs and operational expenditures. Although several statistically significant differences in composition were found between locations, nitrogen treatment, and harvest date, none of these changes were large in magnitude. The remarkable consistency of M. × giganteus composition across different soil types, nitrogen fertilization regimes, and harvest times means accommodating for variation within only a few percentage points rather than larger changes. This suggests that if the same clone of M. × giganteus is used at diverse sites and harvest dates within a region supplying a processing operation, a stable composition will be delivered.

References

Angel J (2010) Climate events of 2009 in Illinois. Illinois State Water Survey. Retrieved April 13, 2012, from http://www.isws.illinois.edu/atmos/statecli/events2009.htm

Arundale RA, Dohleman FG, Heaton EA, McGrath JM, Voigt TB, Long SP (2014a) Yields of Miscanthus x giganteus and Panicum virgatum decline with stand age in the Midwestern USA. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 6(1):1–13

Arundale RA, Dohleman FG, Voigt TB, Long SP (2014b) Nitrogen fertilization does significantly increase yields of stands of Miscanthus x giganteus and Panicum virgatum in multi-year trials in Illinois. BioEnergy Res 7(1):408–416

Baxter LL, Miles TR, Jenkins BM, Milne T, Dayton D, Bryers RW, Oden LL (1998) The behavior of inorganic material in biomass-fired power boilers: field and laboratory experiences. Fuel Process Technol 54(1–3):47–78

Beale CV, Long SP (1995) Can perennial C4 grasses attain high efficiencies of radiant energy conversion in cool climates?. Plant, Cell & Environment, 18: 641–650

Beale CV, Long SP (1997) Seasonal dynamics of nutrient accumulation and partitioning in the perennial C-4-grasses Miscanthus x giganteus and Spartina cynosuroides. Biomass Bioenergy 12(6):419–428

Bhandari HS, Walker DW, Bouton JH, Saha MC (2014) Effects of ecotypes and morphotypes in feedstock composition of switchgrass (Panicum virgatum L.). Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 6(1):26–34

Binod P, Sindhu R, Singhania RR, Vikram S, Devi L, Nagalakshmi S, Kurien N, Sukumaran RK, Pandey A (2010) Bioethanol production from rice straw: an overview. Bioresour Technol 101(13):4767–4774

Byrt CS, Grof CPL, Furbank RT (2011) C4 plants as biofuel feedstocks: optimising biomass production and feedstock quality from a lignocellulosic perspective. J Integr Plant Biol 53(2):120–135

Carroll A, Somerville CR (2009) Cellulosic biofuels. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60:165–182

Christian DG, Riche AB, Yates NE (2008) Growth, yield and mineral content of Miscanthus x giganteus grown as a biofuel for 14 successive harvests. Ind Crop Prod 28(3):320–327

de Vrije T, de Haas GG, Tan, GB, Keijsers ERP, Claassen PAM (2002) Pretreatment of Miscanthus for hydrogen production by Thermotoga elfii. Int J of Hydrogen Energ 27(11–12):1381–1390

Diebold JP (1997) Overview of fast pyrolysis of biomass for the production of liquid fuel. In: Brigwater AV (ed) Developments in thermochemical biomass conversion, vol 1. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London, pp 14–32

DOE (2006) Breaking the biological barriers to cellulosic ethanol: a joint research agenda. Report from the December 2005 Workshop. U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Rockville, pp 1–206

DOE (2012) Theoretical ethanol yield calculator. U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy. Retrieved April 06, 2012, from http://www1.eere.energy.gov/biomass/ethanol_yield_calculator.html

Dohleman FG, Heaton EA, Arundale RA, Long SP (2012) Seasonal dynamics of above- and below-ground biomass and nitrogen partitioning in Miscanthus x giganteus and Panicum virgatum across three growing seasons. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 4(5):534–544

Dohleman FG, Long SP (2009) More productive than maize in the Midwest: how does Miscanthus do it? Plant Physiol 150(4):2104–2115

Du SC, Sun YJ, Gamliel DP, Valla JA, Bollas GM (2014) Catalytic pyrolysis of Miscanthus x giganteus in a spouted bed reactor. Bioresour Technol 169:188–197

FSA (2012) Energy Programs—BCAP Project Areas Listing. Farm Service Agency - US Department of Agriculture. http://www.fsa.usda.gov/FSA Accessed 11/8/14 2014

Ge X, Burner DM, Xu J, Phillips GC, Sivakumar G (2011) Bioethanol production from dedicated energy crops and residues in Arkansas, USA. Biotechnol J 6(1):66–73

Gomez LD, Steele-King CG, McQueen-Mason SJ (2008) Sustainable liquid biofuels from biomass: the writing’s on the walls. New Phytol 178(3):473–485

Greef JM, Deuter M (1993) Syntaxonomy of Miscanthus x giganteus Greef et Deu. Angew Bot 67(3–4):87–90

Ha S-J, Galazka JM, Rin Kim S, Choi J-H, Yang X, Seo J-H, Jin Y-S (2011) Engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae capable of simultaneous cellobiose and xylose fermentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108(2):504–509

Haffner FB, Mitchell VD, Arundale RA, Bauer S (2013) Compositional analysis of Miscanthus giganteus by near infrared spectroscopy. Cellulose 20(4):1629–1637

Han K-J, Pitman WD, Kim M, Day DF, Alison MW, McCormick ME, Aita G (2013) Ethanol production potential of sweet sorghum assessed using forage fiber analysis procedures. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 5(4):358–366

Hayes DJM (2013) Mass and compositional changes, relevant to biorefining, in Miscanthus x giganteus plants over the harvest window. Bioresour Technol 142:591–602

Heaton EA, Dohleman FG, Long SP (2008) Meeting US biofuel goals with less land: the potential of Miscanthus. Glob Chang Biol 14(9):2000–2014

Heaton EA, Dohleman FG, Long SP (2009) Seasonal nitrogen dynamics of Miscanthus x giganteus and Panicum virgatum. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 1:297–307

Heaton EA, Dohleman FG, Miguez AF, Juvik JA, Lozovaya V, Widholm J, Zabotina OA, McIsaac GF, David MB, Voigt TB, Boersma NN, Long SP (2010) Miscanthus: a promising biomass crop. Adv Bot Res 56:75–137

Heim RRJ (2002) A review of twentieth-century drought indices used in the United States. Am Meteorol Soc 83(August):1149–1165

Hill J, Nelson E, Tilman DG, Polasky S, Tiffany D (2006) Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(30):11206–11210

Hodgson EM, Fahmi R, Yates NE, Barraclough T, Shield I, Allison G, Donnison IS (2010) Miscanthus as a feedstock for fast-pyrolysis: does agronomic treatment affect quality? Bioresour Technol 101(15):6185–6191

Hodgson EM, Lister SJ, Bridgwater AV, Clifton-Brown JC, Donnison IS (2010) Genotypic and environmentally derived variation in the cell wall composition of Miscanthus in relation to its use as a biomass feedstock. Biomass Bioenergy 34(5):652–660

Hodgson EM, Nowakowski DJ, Shield I, Riche AB, Bridgwater AV, Clifton-Brown JC, Donnison IS (2011) Variation in Miscanthus chemical composition and implications for conversion by pyrolysis and thermo-chemical bio-refining for fuels and chemicals. Bioresour Technol 102(3):3411–3418

Hodkinson TR, Renvoize S (2001) Nomenclature of Miscanthus x giganteus (Poaceae). Kew Bull 56(3):759–760

Huyen TLN, Remond C, Dheilly RM, Chabbert B (2010) Effect of harvesting date on the composition and saccharification of Miscanthus x giganteus. Bioresour Technol 101(21):8224–8231

Kim SR, Ha S, Wei N, Oh EJ, Jin Y (2012) Simultaneous co-fermentation of mixed sugars: a promising strategy for producing cellulosic ethanol. Trends Biotechnol 30(5):274–282

Lemus R, Charles Brummer E, Lee Burras C, Moore KJ, Barker MF, Molstad NE (2008) Effects of nitrogen fertilization on biomass yield and quality in large fields of established switchgrass in southern Iowa, USA. Biomass Bioenergy 32(12):1187–1194

Lewandowski I (2003) The development and current status of perennial rhizomatous grasses as energy crops in the US and Europe. Biomass Bioenergy 25(4):335–361

Lewandowski I, Clifton-Brown JC, Andersson B, Basch G, Christian DG, Jorgensen U, Teixeira F (2003) Environment and harvest time affects the combustion qualities of Miscanthus genotypes. Agron J 53(4):190–199

Lewandowski I, Heinz A (2003) Delayed harvest of miscanthus—influences on biomass quantity and quality and environmental impacts of energy production. Euro J Agron 19(1):45–63

Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O (2006) SAS for mixed models. Forestry, 2nd edn. SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, pp 1–814

Liu X-JA, Fike JH, Galbraith JM, Fike WB, Parrish DJ, Evanylo GK, Strahm BD (2015) Effects of harvest frequency and biosolids application on switchgrass yield, feedstock quality, and theoretical ethanol yield. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 7(1):112–121

Lygin AV, Upton J, Dohleman FG, Juvik JA, Zabotina OA, Widholm JM, Lozovaya VV (2011) Composition of cell wall phenolics and polysaccharides of the potential bioenergy crop—Miscanthus. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 3(4):333–345

Magid J, Luxhoi J, Lyshede OB (2004) Decomposition of plant residues at low temperatures separates turnover of nitrogen and energy rich tissue components in time. Plant and Soil 258(2):351–365

Meehan PG, Finnan JM, Mc Donnell KP (2013) The effect of harvest date and harvest method on the combustion characteristics of Miscanthus x giganteus. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 5(5):487–496

Maughan M, Bollero GA, Lee DK, Darmody R, Bonos S, Cortese LM, Murphy J, Gaussoin R, Sousek M, Williams D, Williams L, Miguez FE, Voigt TB (2011) Miscanthus x giganteus productivity: the effects of management in different environments. Glob Chang Biol Bioenergy 4(2):253–265

Oasmaa A, Czernik S (1999) Fuel oil quality of biomass pyrolysis oils—state of the art for the end users. Energy Fuel 13(4):914–921

Palmer WC (1965) Meteorological drought. Research Paper 45, U.S. Dept. of Commerce, 58 pp

Pauly M, Keegstra K (2008) Cell-wall carbohydrates and their modification as a resource for biofuels. Plant J 54(4):559–568

Rubin EM (2008) Genomics of cellulosic biofuels. Nature 454(7206):841–845

Sannigrahi P, Ragauskas AJ (2010) Poplar as a feedstock for biofuels: a review of compositional characteristics. Biofuels Bioprod Biorefin 4(2):209–226

Sluiter JB, Ruiz RO, Scarlata CJ, Sluiter AD, Templeton DW (2010) Compositional analysis of lignocellulosic feedstocks. 1. Review and description of methods. J Agric Food Chem 58(16):9043–9053

Strullu L, Cadoux S, Preudhomme M, Jeuffroy M-H, Beaudoin N (2011) Biomass production and nitrogen accumulation and remobilisation by Miscanthus x giganteus as influenced by nitrogen stocks in belowground organs. Field Crop Res 121(3):381–391

Templeton DW, Scarlata CJ, Sluiter JB, Wolfrum EJ (2010) Compositional analysis of lignocellulosic feedstocks 2. Method uncertainties. J Agric Food Chem 58(16):9054–9062

Templeton DW, Sluiter AD, Hayward TK, Hames BR, Thomas SR (2009) Assessing corn stover composition and sources of variability via NIRS. Cellulose 16(4):621–639

Tuskan G, West D, Bradshaw HD, Neale D, Sewell M, Wheeler N, Megraw B, Jech K, Wiselogel A, Evans R, Elam C, Davis M, Dinus R (1999) Two high-throughput techniques for determining wood properties as part of a molecular genetics analysis of hybrid poplar and loblolly pine. Appl Brioche Biotechnol 77:55–65

USDA (2011) Planting and managing giant Miscanthus as a biomass energy crop, Technical Note No. 4. Plants Material Program. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington, DC

USDA (2012a) Soils. Natural Resources Conservation Service. (n.d.). NSSH part 622: Ecological and interpretative groups. Retrieved March 22, 2012, from http://soils.usda.gov/technical/handbook/contents/part622.html

USDA (2012b) Web soil survey. Natural Resources Conservation Service. Web soil survey. Retrieved March 22, 2012, from http://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov/app/WebSoilSurvey.aspx

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Energy Biosciences Institute. Special thanks to Noel Piatek, Ben Lewis, Ethan Kessler, Mike Hradek, Ariel Raneiri, Liz Vonderhaar, Neal Makela, John Jurveis, and Keith Chan for their help in collecting and processing samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Table 1

(RTF 286 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

(RTF 116 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Arundale, R.A., Bauer, S., Haffner, F.B. et al. Environment Has Little Effect on Biomass Biochemical Composition of Miscanthus × giganteus Across Soil Types, Nitrogen Fertilization, and Times of Harvest. Bioenerg. Res. 8, 1636–1646 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-015-9613-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12155-015-9613-2