Abstract

Self-criticism has been considered as a transdiagnostic dimension that contributes to the development of several mental health difficulties. Moreover, there is a significant association between self-criticism and emotion regulation difficulties. Of special interest are two variables, related to emotion dysregulation, that have garnered significant attention in recent years: emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions. By contrast, increased self-compassion has been proposed as a protective mechanism of mental health symptoms, specifically depression. The present study used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to investigate the relationship between self-criticism, self-compassion, and depressive symptoms, while considering emotional overproduction and perseveration of negative emotions as mediating variables. A cross-sectional design was used. The sample consisted of 453 participants who completed measures of self-criticism, self-compassion, depressive symptoms, emotional overproduction, and perseveration of negative emotions. Results indicate that emotional overproduction mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. Additionally, both emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions mediate the negative association between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Therefore, developing self-compassion may diminish the negative impact of self-criticism on depressive symptoms through these two variables. In conclusion, this study deepens our understanding of the mechanism by which self-compassion can mitigate mental health problems such as depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Self-criticism refers to a self-evaluative process whereby individuals judge themselves negatively through hostile inner dialogues when they face failures or difficulties (Navarrete et al., 2021). Recent reviews have demonstrated that it plays an important role in the development of a wide range of disorders, considering it to be a transdiagnostic dimension and a vulnerability factor that contributes to the development and maintenance of several mental health difficulties (Gilbert & Irons, 2005; Werner et al., 2019). It should be noted that the literature is particularly consistent when it comes to relating self-criticism to depressive symptoms, in both adults (Petrocchi et al., 2019; Aruta et al., 2021; Powers et al., 2023) and children (McIntyre et al., 2018; Barcaccia et al., 2020).

In that regard, from the Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) framework, Gilbert (2014) explains that people who are very self-critical have an increased sensitivity and hyperactivity to the threat and self-protection system, one of the three types of emotion regulation systems distinguished within CFT. As a result, self-critical individuals generate very easily different types of emotions such as sadness, anxiety or anger, and these emotions tend to perseverate longer than in non-self-critical people. In this line, a growing body of research has highlighted the significant association between self-criticism and emotion dysregulation, characterized by difficulties in effectively managing and modulating emotions (Inwood & Ferrari, 2018; Sharpe et al., 2024). In turn, this construct is itself a transdiagnostic factor, primarily associated with mood disorders (Cludius et al., 2020; Gadassi-Polack et al., 2021). Concretely, within the different factors that define emotion dysregulation, emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions have garnered significant interest in recent years.

On the one hand, emotional overproduction is the propensity to simultaneously experience high number of negative emotions during sad episodes (Hervas & Vazquez, 2011). In their study, Hervas and Vazquez (2011) analyzed the association between emotional overproduction, rumination, and depression. They concluded that rumination fosters emotional overproduction and, at the same time, emotional overproduction enhances rumination, creating a self-perpetuating cycle that leads to depression. Other recent studies have come to the same conclusion (Villalobos et al., 2021; Singh & Mishra, 2023). This cycle might be fostered when the content of rumination is self-critical. In fact, self-criticism is frequently combined with a ruminative thinking style, resulting in a repetitive hostile inner dialogue conceptualized as “self-critical rumination” (Martínez-Sanchis et al., 2021). On the other hand, the perseveration of emotions is the tendency to experience prolonged emotional reactions once elicited, which is strongly associated with psychopathology (Boyes et al., 2017; Becerra et al., 2019). Specifically, it has been associated to depression, higher psychological distress, anxiety, and stress (Ripper et al., 2018). Besides, some authors argue that affective chronometry, the temporal dynamics of the emotional response, is the key to understanding individual differences in affective style and vulnerability to psychopathology (Davidson, 1998; Kohn & Keller, 2023).

Finally, self-compassion is the emotion regulation strategy that has received more attention in the last years as the ‘antidote’ to self-criticism (Wakelin et al., 2022). Research has shown that they are two independent processes related to different neural correlates and affective and physiological systems (López et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2022). In addition, these two constructs have a negative correlation, given that higher levels of self-compassion are associated with lower levels of self-criticism, and vice versa (Boyraz et al., 2021; Collman et al., 2024). Self-compassion is the ability to extend kindness and understanding to oneself rather than harsh judgment during failure or suffering (Neff, 2003). Evidence suggests that increased self-compassion is linked to lower levels of mental health symptoms (Kurebayashi & Sugimoto, 2022). In particular, literature has established that it plays a protective role not only in the development, but also in the maintenance and treatment of depression (Pullmer et al., 2019; Adie et al., 2021; Wang & Wu., 2024). Moreover, recent studies have suggested that self-compassion could ameliorate the negative impact of self-criticism on depressive symptoms, so the positive association between self-criticism and depression may be buffered by enhanced levels of self-compassion (Kaurin et al., 2018; Wakelin et al., 2022; Ondrejková et al., 2022).

Therefore, the scientific literature establishes a clear relationship between self-criticism, self-compassion, and depressive symptoms. However, the specific mechanism underlying this relationship has received much less attention. The present study aims to address this research gap by proposing two primary objectives: first, to confirm that increased self-compassion can mitigate the negative impact of self-criticism on depressive symptoms; and second, to elucidate the precise explanatory mechanism involved in this interaction. Specifically, given the association of these variables with emotional dysregulation, we propose that it may be mediated by a reduction in emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions. In order to achieve these aims, we posit the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1: Self-criticism will be positively associated with depressive symptoms; besides, emotional overproduction and perseveration of negative emotions will mediate this link.

-

Hypothesis 2: Self-criticism will be negatively associated with self-compassion.

-

Hypothesis 3: Self-compassion will be negatively associated with depressive symptoms, and again emotional overproduction and perseveration of negative emotions will be the mediating variables of this link.

Method

Participants and procedure

The sample consisted of 453 participants who volunteered to participate in the study. The majority of the participants were females (74.8%), ranging from 18 to 73 years of age (M = 31.40, SD = 13.039). They were mostly single (72.8%) and had completed higher education (83.5%). Concerning employment status, 48.3% were students, 40.4% were employed, 8.2% were unemployed and 3.1% were retired. Participant characteristics are listed in Table 1.

The Ethics Committee of Research in Humans of the Ethics Commission of the University of Valencia approved the procedure (H1539699805131). Participants were required to meet two inclusion criteria: being over 18 years old and having an advanced level of Spanish proficiency. The exclusion criteria included having a diagnosed serious mental disorder or addiction problems. They were recruited through social media and flyers announcing the study at the University of Valencia and Jaume I University of Castellon (Spain). We obtained written consent from all participants involved in this study and the assessment was conducted between September of 2019 and March of 2020. All interested participants received an e-mail with a link to access the online questionnaires displayed on a data collection website (LimeSurvey®).

Measures

Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale - Short Form (FSCRS-SF; Sommers-Spijkerman et al., 2018)

The FSCRS-SF is the 14-item form of the FSCRS (Gilbert et al., 2004), which assesses people’s reactions to situations of stress or failure. It consists of three subscales: Inadequate Self (IS), Hated Self (HS) and Reassured Self (RS); with five, four, and five items, respectively. Participants respond on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all like me) to 4 (Extremely like me), with higher scores indicating a greater sense of inadequacy (score 0–20), self-hate (score 0–16), and self-reassurance (score 0–20). In this study, we only used the IS and HS subscales, given that their combination determines the self-criticism levels (score 0–36). We used the translated and validated Spanish version (Navarrete et al., 2021). In this sample, the combination of IS and HS subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.84, ω = 0.88).

Self-Compassion Scale - Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al., 2011)

The SCS-SF is a 12-item measure assessing the six components of self-compassion: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification (Neff, 2003). Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always). A mean score was computed, resulting in total self-compassion scores ranging from 1 to 5. We used the Spanish validated version, which reported good internal consistency (Garcia-Campayo et al., 2014). In the present sample, the internal consistency has also been found to be good (α = 0.86, ω = 0.89).

Emotional Reactivity Intensity and Perseveration Scale (ERIPS; Ripper et al., 2018)

It is a 60-item scale that assesses individual differences in dispositional emotional reactivity, intensity, and perseveration. The ERIPS is based on the original 20 adjectives of the Positive and Negative Affect Scales (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), but the instructions and response options have been adapted to reflect reactivity, intensity, and perseveration of positive and negative emotions. In this study, we only used the perseveration of negative emotions subscale of the ERIPS, whose instructions are: “When you are experiencing a situation that does make you feel this way, how long is this feeling likely to persist?”. Furthermore, in our study, we replaced the 20 emotions from the PANAS with the 23 negative emotions from the Discrete Emotions Questionnaire (DEQ; Harmon-Jones et al., 2016). We made this change because the DEQ assesses the full spectrum of basic emotions and has been found to be more sensitive than the PANAS in measuring self-reported discrete emotions (Harmon-Jones et al., 2016). Specifically, participants rated the 23 Likert-type items with five response options (ranging from 1 = Not at all persistent to 5 = Extremely persistent), resulting in a total score ranging from 23 to 115. In this sample, the psychometric properties of the perseveration of negative emotions subscale showed good internal consistency (α = 0.86, ω = 0.95).

Emotional Overproduction Scale (EOPS; Hervas & Vazquez, 2011)

In this 13-item scale, participants rate the degree to which they normally experience additional negative emotions during episodes of sadness. Each item is evaluated on a five-point Likert scale, spanning from 1 = Never to 5 = Always (score 13–65). The Spanish version of EOPS shows evidence of reliability and good internal consistency (Hervas & Vazquez, 2011; Montero-Marin et al., 2019). In this study, the scale also demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.91, ω = 0.92).

Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18; Derogatis, 2000)

This 18-item scale assesses depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms. The items are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Always). In this study, we only used the depression subscale (BSI-D, 6 items, score 0–24), which evaluates the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past week. The BSI-18 has good dimensional structure and reliability in the Spanish population (Galdón et al., 2008). In this sample, the depression subscale of the BSI-18 shows excellent internal consistency (α = 0.86, ω = 0.89).

Data analysis

First, descriptive analyses of the demographic characteristics of the sample were explored. Means, medians, standard deviations, mean absolute deviations, as well as the minimum and maximum scores, skewness and kurtosis values of psychological variables were computed. In addition, a visual inspection was carried out through the histograms and boxplot of the variables. The assumption of normality was evaluated with each of the Q-Q plots of the variables. Furthermore, multivariate normality was tested using Mardia coefficients of kurtosis and asymmetry. Missing data were handled using listwise deletion method, given that not more than 5% of the sample showed missing values in the variables of interest. We did not find any outliers, using the Tukey’s rule of thumb (Values more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the quartiles — either below Q1 − 1.5IQR, or above Q3 + 1.5IQR).

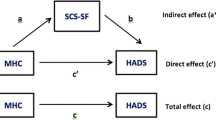

Internal consistency was analyzed through Cronbach’s Alpha (α). In addition, McDonald’s Omega (ω) was included, given that this index is unbiased and overperforms Cronbach’s Alpha (Dunn et al., 2014). Subsequently, a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was tested, including exclusively manifest variables. The estimation method selected was the robust version of Maximum Likelihood (ML) due to the violation of the multivariate normality assumption (multivariate skewness = 242.98, p <.001, multivariate kurtosis = 4.20, p <.001). The proposed model is shown in Fig. 1.

To find out the impact of self-compassion and self-criticism on depressive symptoms, through the perseveration of negative emotions and the emotional overproduction, indirect effects with confidence intervals were calculated using the bootstrapping resampling method (5000 bootstrap samples). In order to assess goodness of fit, χ2 statistic (p >.05), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (≥ 0.95 indicating an excellent fit and ≥ 0.90 indicating a good fit), and Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) (≤ 0.08, indicating good fit) were chosen, based on the proposals of Hu and Bentler (2009). Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), which are usually reported, were not calculated given that the model shows 1 degree of freedom, and these indices underperform in models with small degrees of freedom (Kenny et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2019). Furthermore, to reduce the probability of type I error (rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true), the p values were corrected using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method, as recommended for SEM by Cribbie (2007).

All data analyses were carried out using R 4.1.3 and Rstudio (R Core Team, 2022). Descriptive analysis and reliability were computed using the psych package (Rewelle, 2014), the path analysis model was computed using lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), and p values were adjusted using stats package (R Core Team, 2022).

Results

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics of all the psychological variables. Additionally, zero-order Pearson’s correlations of each variable are shown in Table 3. Results show that self-criticism is positively correlated with depressive symptoms, emotional overproduction, and the perseveration of negative emotions (p <.001), while it is negatively associated to self-compassion (p <.001). On the contrary, self-compassion is negatively correlated with all study variables (p <.001). Furthermore, there is a positive association between perseveration of negative emotions and emotional overproduction (p <.001). These correlations form the foundation of the proposed model.

Regarding the structural equation analysis, the proposed model adequately fits with our data (χ2(1) = 25.65, p <.001, CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.035). The structural equation model with standardized estimation parameters is depicted in Fig. 2. It shows that self-criticism significantly predicts the perseveration of negative emotions (β = 0.241, p <.001) and emotional overproduction (β = 0.416, p <.001). In turn, the perseveration of negative emotions (β = 0.116, p <.05) and emotional overproduction (β = 0.325, p <.001) significantly predict depressive symptoms. Conversely, self-compassion also predicts the perseveration of negative emotions (β = − 0.397, p <.001) and emotional overproduction (β = − 0.37, p <.001), being the relationship between self-compassion and these two variables negative.

Standardized coefficients of the structural equation model. Note. Path diagrams are shown with the standardized coefficients, the covariance between the perseveration of negative emotions and emotional overproduction, and the proportion of variance explained by each of the endogenous variables (R2). * indicates p <.05. *** indicates p <.001

Concerning the indirect effects, emotional overproduction mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms (β = 0.135, SE = 0.034, p <.001, 95% CI [0.069, 0.201]), but the perseveration of negative emotions does not mediate this relationship (β = 0.028, SE = 0.015, p =.056, 95% CI [− 0.001, 0.057]). In addition, the indirect effect of self-compassion on depressive symptoms through the perseveration of negative emotions (β = − 0.046, SE = 0.019, p =.017, 95% CI [-0.084, − 0.008]) and through emotional overproduction (β = − 0.120, SE = 0.024, p <.001, 95% CI [-0.167, − 0.074]) were also calculated, both being significant. Overall, 44% of the variance in depressive symptoms can be attributed to the set of predictive variables. Similarly, the variables also explain 35% of the perseveration of negative emotions and 53% of emotional overproduction.

Discussion

In this study, we tested a possible explanatory mechanism model for understanding the relationship between self-criticism, self-compassion, and depressive symptoms. Specifically, the novelty of this research lies in the exploration of two pivotal variables pertaining to emotion dysregulation as mediating factors: emotional overproduction and perseveration of negative emotions.

The strong association between self-criticism and depressive symptoms found is consistent with a substantial body of scientific literature (McIntyre et al., 2018; Petrocchi et al., 2019; Barcaccia et al., 2020; Aruta et al., 2021; Powers et al., 2023). Moreover, our data indicate that self-criticism is a significant predictor of both the perseveration of negative emotions and emotional overproduction. Furthermore, both variables emerge as significant predictors of depressive symptoms. These results support Gilbert’s (2014) proposal that individuals with a tendency for self-criticism have an increased sensitivity and hyperactivity to the threat and self-protection system. As a result, they are more prone to experiencing a diverse range of negative emotions and these emotions tend to persist for longer periods of time.

However, with regard to the indirect effects, only emotional overproduction mediates the relationship between self-criticism and depressive symptoms, while the perseveration of negative emotions does not mediate this link. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was only partially supported. It should be noted that the perseveration of negative emotions approaches the level of significance (p =.056), so we expect that it would be reached with a larger sample size. Hence, we consider that this variable has a notable influence in the association between self-criticism and depressive symptoms, but it could not be detected in our sample. Still, it is important to highlight that, in our model, the quantity of emotions experienced, rather than the duration of negative emotions, plays a significant role in explaining the link between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. This heightened impact of emotion quantity compared to its duration requires further investigation in future studies. Consequently, this result unveils new areas for research, such as exploring the consistency of these findings across diverse populations or contexts.

Our findings reveal that self-compassion is negatively associated with self-criticism, which confirms Hypothesis 2 and is also consistent with previous scientific research (Boyraz et al., 2021; Collman et al., 2024). Moreover, the results show a robust and negative association between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. This is not surprising, given how the literature has established self-compassion as a protective factor against depression (Pullmer et al., 2019; Adie et al., 2021; Wang & Wu, 2024). Furthermore, we found that self-compassion predicts the perseveration of negative emotions and emotional overproduction, and in addition, the indirect effect of self-compassion on depressive symptoms through these two variables is negative and significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was validated. These results are consistent with The Self-Regulation Resource Model (SRRM; Sirois, 2015), which suggests that self-compassion may enhance individuals’ self-regulation abilities by reducing their involvement with negative emotions and at the same time promoting positive emotions. In a systematic review evaluating the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation and mental health, Inwood and Ferrari (2018) found support for emotion regulation as the mediator between self-compassion and a range of mental health symptoms, including depression.

In view of all these findings, we can assert that increased self-compassion can mitigate the adverse effects of self-criticism on depressive symptoms. Therefore, consistent with our first objective, this relationship has been successfully reproduced, as previously reported in the scientific literature (Kaurin et al., 2018; Wakelin et al., 2022; Ondrejková et al., 2022). Hence, nurturing self-compassion emerges as a paramount factor in fostering mental health. Fortunately, multiple interventions based on self-compassion have been developed (Kirby, 2017), and recent meta-analyses indicate that they result in a significant reduction in self-criticism (Wakelin et al., 2022; Vidal & Soldevilla, 2023). However, in accordance with our second objective, the novelty and specific contribution of this study lies in its elucidation of the precise mechanism through which self-compassion alleviates depressive symptoms, namely, by attenuating excessive emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions. This is in line with the suggestions of Kirby et al. (2017) for future research in the field of compassion, who emphasize the need to identify the specific mechanisms of change, in order to better understand how compassion interventions work.

Limitations and future research

The present study has some limitations that should be mentioned. First, given its cross-sectional nature, causal inferences between the variables cannot be made. Thus, future research should consider longitudinal data collection. Second, our sample predominantly consisted of women and university students; therefore, generalizing current results to other types of populations may not be appropriate. Additionally, the recruitment of a community sample restricts the inference of our findings to clinical populations. Indeed, the depressive symptoms scores were predominantly low, complicating the generalization of this model to populations with severe depression scores. Further investigation with clinical samples is required to gain deeper insights into how the studied variables operate across diverse populations. Finally, self-report measures exhibit certain limitations that require careful consideration, including memory bias, social desirability, and the potential for random or acquiescent responding (Paulhus & Vazire, 2007). Therefore, it is important for future studies to integrate additional sources of information, such as Ecological Momentary Assessment or naturalistic observation research.

Conclusion

This study proposes a potential explanatory mechanism of how self-criticism and self-compassion are related to depressive symptoms, while taking into account two central variables related to emotion dysregulation as mediating factors: emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions. To our knowledge, this is the first study that explored the variables underlying the relationship between these constructs. Our results indicate that emotional overproduction mediates the association between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. Additionally, both emotional overproduction and the perseveration of negative emotions mediate the negative association between self-compassion and depressive symptoms. Therefore, the development of self-compassion may diminish the negative effects of self-criticism on depressive symptoms through these two variables.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Adie, T., Steindl, S. R., Kirby, J. N., Kane, R. T., & Mazzucchelli, T. G. (2021). The relationship between self-compassion and depressive symptoms: Avoidance and activation as mediators. Mindfulness,12(7), 1748–1756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01637-1

Aruta, J. J. B. R., Antazo, B., Briones-Diato, A., Crisostomo, K., Canlas, N. F., & Peñaranda, G. (2021). When does self-criticism lead to depression in collectivistic context. International Journal for the Advancement of Counseling,43(1), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-020-09418-6

Barcaccia, B., Salvati, M., Pallini, S., Baiocco, R., Curcio, G., Mancini, F., & Vecchio, G. M. (2020). Interpersonal forgiveness and adolescent depression. The mediational role of self-reassurance and self-criticism. Journal of Child and Family Studies,29(2), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01550-1

Becerra, R., Preece, D., Campitelli, G., & Scott-Pillow, G. (2019). The assessment of emotional reactivity across negative and positive emotions: Development and validation of the Perth emotional reactivity scale (PERS). Assessment,26(5), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191117694455

Boyes, M. E., Carmody, T. M., Clarke, P. J. F., & Hasking, P. A. (2017). Emotional reactivity and perseveration: Independent dimensions of trait positive and negative affectivity and differential associations with psychological distress. Personality and Individual Differences,105, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.025

Boyraz, G., Legros, D. N., & Berger, W. B. (2021). Self-criticism, self-compassion, and perceived health: Moderating effect of ethnicity. The Journal of General Psychology,148(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2020.1746232

Cludius, B., Mennin, D., & Ehring, T. (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion,20(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000646

Collman, S., Heriot-Maitland, C., Peters, E., & Mason, O. (2024). Investigating associations between self-compassion, self‐criticism and psychotic‐like experiences. Psychology and Psychotherapy,97(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12500

Cribbie, R. A. (2007). Multiplicity control in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling,14(1), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1401_5

Davidson, R. J. (1998). Affective style and affective disorders: Perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cognition and Emotion,12(3), 307–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379628

Derogatis, L. R. (2000). The brief symptom inventory-18 (BSI-18): Administration. In Scoring, and procedures manual (3rd ed.). National Computer Systems.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology,105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Gadassi-Polack, R., Everaert, J., Uddenberg, C., Kober, H., & Joormann, J. (2021). Emotion regulation and self-criticism in children and adolescence: Longitudinal networks of transdiagnostic risk factors. Emotion,21(7), 1438–1451. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001041

Galdón, M. J., Durá, E., Andreu, Y., Ferrando, M., Murgui, S., Pérez, S., & Ibañez, E. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 in a Spanish breast cancer sample. Journal of Psychosomatic Research,65(6), 533–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.05.009

Garcia-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., Andrés, E., Montero-Marin, J., López-Artal, L., & Demarzo, M. M. (2014). Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health and Quality of life Outcomes,12, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-4

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. British Journal of Clinical Psychology,53(1), 6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043

Gilbert, P., & Irons, C. (2005). Focused therapies and compassionate mind training for shame and self-attacking. In P. Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research and use in psychotherapy (pp. 263–325). Routledge.

Gilbert, P., Clarke, M., Hempel, S., Miles, J. N. V., & Irons, C. (2004). Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology,43(1), 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812959

Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016). The discrete emotions questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emotions. PloS One,11(8), e0159915. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159915

Hervas, G., & Vazquez, C. (2011). What else do you feel when you feel sad? Emotional overproduction, neuroticism and rumination. Emotion,11(4), 881–895. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021770

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (2009). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal,6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology Health Well Being,10(2), 215–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12127

Kaurin, A., Schönfelder, S., & Wessa, M. (2018). Self-compassion buffers the link between self-criticism and depression in trauma-exposed firefighters. Journal of Counseling Psychology,65(4), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000275

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research,44(3), 486–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

Kirby, J. N. (2017). Compassion interventions: The programmes, the evidence, and implications for research and practice. Psychology and Psychotherapy,90(3), 432–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12104

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy,48(6), 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

Kohn, R., & Keller, M. B. (2023). Emotions. In Tasman’s psychiatry (pp. 1–34). Springer International Publishing.

Kurebayashi, Y., & Sugimoto, H. (2022). Self-compassion and related factors in severe mental illness: A scoping review. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care,58(4), 3044–3061. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.13017

López, A., Sanderman, R., Smink, A., Zhang, Y., van Sonderen, E., Ranchor, A., & Schroevers, M. J. (2015). A reconsideration of the self-compassion scale’s total score: Self-compassion versus self-criticism. PloS One,10(7), e0132940. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132940

Martinez-Sanchis, M., Navarrete, J., Cebolla, A., Molinari, G., Vara, M. D., Banos, R. M., & Herrero, R. (2021). Exploring the mediator role of self-critical rumination between emotion regulation and psychopathology: A validation study of the Self-Critical Rumination Scale (SCRS) in a spanish-speaking sample. Personality and Individual Differences,183, 111115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111115

McIntyre, R., Smith, P., & Rimes, K. A. (2018). The role of self-criticism in common mental health difficulties in students: A systematic review of prospective studies. Mental Health and Prevention,10, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.02.003

Montero-Marin, J., Perez-Yus, M. C., Cebolla, A., Soler, J., Demarzo, M., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2019). Religiosity and meditation practice: Exploring their explanatory power on psychological adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology,10, 630. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00630

Navarrete, J., Herrero, R., Soler, J., Domínguez-Clavé, E., Baños, R., & Cebolla, A. (2021). Assessing self-criticism and self-reassurance: Examining psychometric properties and clinical usefulness of the Short-Form of the Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking & Self-Reassuring Scale (FSCRS-SF) in Spanish sample. PloS one,16(5), e0252089. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252089

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity,2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Ondrejková, N., Halamová, J., & Strnádelová, B. (2022). Effect of the intervention mindfulness based compassionate living on the - level of self-criticism and self-compassion. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.),41(5), 2747–2754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00799-w

Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). The Guilford Press.

Petrocchi, N., Dentale, F., & Gilbert, P. (2019). Self-reassurance, not self-esteem, serves as a buffer between self-criticism and depressive symptoms. Psychology and Psychotherapy,92(3), 394–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12186

Powers, T. A., Moore, E., Levine, S., Holding, A., Zuroff, D. C., & Koestner, R. (2023). Autonomy support buffers the impact of self-criticism on depression. Personality and Individual Differences,200(111876), 111876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111876

Pullmer, R., Chung, J., Samson, L., Balanji, S., & Zaitsoff, S. (2019). A systematic review of the relation between self-compassion and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence,74, 210–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.006

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from http://www.r-project.org/

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy,18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Rewelle, W. (2014). psych. In Procedures for personality and psychological research. Northwestern University, Evanston. Version 1.4.8. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from http://cran.r-project.org/package=psych

Ripper, C. A., Boyes, M. E., Clarke, P. J., & Hasking, P. A. (2018). Emotional reactivity, intensity, and perseveration: Independent dimensions of trait affect and associations with depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences,121, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.032

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. Retrieved September 23, 2022, from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/

Sharpe, E. E., Schofield, M. B., Roberts, B. L. H., Kamal, A., & Maratos, F. A. (2024). Exploring the role of compassion, self-criticism and the dark triad on obesity and emotion regulation. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N. J.),43(13), 11972–11982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05319-0

Shi, D., Lee, T., & Maydeu-Olivares, A. (2019). Understanding the model size effect on SEM fit indices. Educational and Psychological Measurement,79(2), 310–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164418783530

Singh, P., & Mishra, N. (2023). Rumination moderates the association between neuroticism, anxiety and depressive symptoms in Indian women. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine,45(6), 614–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176231171949

Sirois, F. M. (2015). A self-regulation resource model of self-compassion and health behavior intentions in emerging adults. Preventive Medicine Reports,2, 218–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.03.006

Sommers-Spijkerman, M., Trompetter, H., Klooster, T., Schreurs, P., Gilbert, K., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2018). Development and validation of the forms of self-criticizing/attacking and self-reassuring scale-short form. Psychological Assessment,30(6), 729–743. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000514

Vidal, J., & Soldevilla, J. M. (2023). Effect of compassion-focused therapy on self-criticism and self-soothing: A meta-analysis. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology,62(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12394

Villalobos, D., Pacios, J., & Vázquez, C. (2021). Cognitive control, cognitive biases and emotion regulation in depression: A new proposal for an integrative interplay model. Frontiers in Psychology,12, 628416. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628416

Wakelin, K. E., Perman, G., & Simonds, L. M. (2022). Effectiveness of self-compassion-related interventions for reducing self-criticism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy,29(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2586

Wang, T., & Wu, X. (2024). Self-compassion moderates the relationship between neuroticism and depression in junior high school students. Frontiers in psychology,15, 1327789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1327789

Wang, Y., Wu, R., Li, L., Ma, J., Yang, W., & Dai, Z. (2022). Common and distinct neural substrates of the compassionate and uncompassionate self-responding dimensions of self-compassion. Brain Imaging and Behavior,16(6), 2667–2680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-022-00723-9

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,54(6), 1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Werner, A. M., Tibubos, A. N., Rohrmann, S., & Reiss, N. (2019). The clinical trait self-criticism and its relation to psychopathology: A systematic review– update. Journal of Affective Disorders,246, 530–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.069

Acknowledgements

J.V. is supported by their grant FPU21/03164, funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation/State Research Agency/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 and by the European Social Fund - Investing in your future.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. This work was supported by CIBEROBN, an initiative of the ISCIII (ISC III CB06 03/0052), to CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP CB22/02/00052; ISCIII), and Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (Spain) under AMABLE-VR (RTI2018-097835-A-I00).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.V.: Conceptualization, Writing the Original Draft. V.C.-M.: Methodology, Formal analysis. J.N.: Investigation (recruitment), Data Curation. J.S.: Supervision. C.S.: Writing (Review & Editing). G.M.: Writing (Review & Editing). A.C.: Conceptualization, Writing (Review & Editing), Supervision.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical committee of the University of Valencia (Spain) (reference number: H1539699805131).

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used Chat-GPT to enhance the clarity of the English expression in the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Joana Vidal and Víctor Ciudad-Fernández have contributed equally to this work and are willing to share first authorship.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vidal, J., Ciudad-Fernández, V., Navarrete, J. et al. From self-criticism to self-compassion: exploring the mediating role of two emotion dysregulation variables in their relationship to depressive symptoms. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06325-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06325-6