Abstract

This study aimed to test the validity and reliability of the ICU Psychosocial Care Scale in Turkish, which was developed to measure the psychosocial care of cardiac critical patients. This study was a methodological design. The study sample consisted of 180 critically ill cardiac patients meeting the inclusion criteria. The study used the ICU-Psychosocial Care (ICU-PC) Scale and The Intensive Care Experiences Scale for data collection. Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.0 and AMOS V 24.0 statistical package programs. Content validity, construct validity, reliability and concurrent validity tests were performed. The sample (n = 180) was predominantly male (66.1%) with a mean age of 65.96 ± 15.46 years. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to confirm the 3-dimensional and 14-item structure of the scale. The fit indices of the scale were found to be χ2 = 89.24, df = 52, χ2/df = 1.716, goodness of fit index = 0.94, comparative fit index = 0.97, incremental fit index = 0.97, Tucker-Lewis index = 0.95, root mean square error of approximation = 0.05, standardized root mean square residual = 0.05. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of ICU-PC scale was 0.87. The ICU-PC scale is a valid, reliable and distinctive scale in assessing the psychosocial care of critically ill cardiac patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intensive care units (ICUs) in the hospital environment are the units that provide care with the most advanced technology possible to patients with the most serious medical and surgical diseases (Berthelsen & Cronqvist, 2003; Karlsson et al., 2021). ICUs are different from other units in terms of the characteristics of patients and diseases, treatment methods, physical characteristics and emotional environment (Chivukula et al., 2017). A critical care patient is an individual whose physiological balance is impaired, who needs to be monitored regularly, whose health status threatens to become serious, and who requires supportive treatment for organs and systems (Booker, 2015). Attempts made for the benefit of the patient to control the physical illness, the tools used, provide life support to the patient, and at the same time cause the patient to experience psychosocial problems (Wenham & Pittard, 2009). For this reason, contrary to the traditional approach in patient care, a holistic approach that addresses the physical, spiritual and social needs of the individual, family and society should be adopted in the ICUs (Zamanzadeh et al., 2015; Ventegodt et al., 2016). Holistic patient-centered care form the framework for the psychosocial care of patients with physical illness and their families (Hariharan et al., 2015; Zamanzadeh et al., 2015; Arslan & Yazıcı, 2021).

Being in the hospital is a stressful situation regardless of the unit (Di Gangi et al., 2013). However, ICUs are complex units where patients are exposed to physical and psychosocial stressors. Many factors such as the large number of patients, noise caused by healthcare professionals and devices, procedures performed during treatment and care, special diagnostic tests, temperature and light levels of the environment, feeling of loneliness, fear of death and the unknown arising from the disease, and pain affect patient comfort and cause stress. (Wenham & Pittard, 2009; Chivukula et al., 2017). Cardiac surgery patients need to stay in intensive care for 2–3 days during which they recover under close monitoring. Staying in such an environment—a “dark vortex”—affects the patient’s physical and psychological mood, causing greater stress in critically ill cardiac patients (Almerud et al., 2008; Wenham & Pittard, 2009; Galazzi et al., 2021). For this reason, it is important for nurses to meet the patient’s physiological needs as well as their psychosocial needs in evaluating cardiac patient as a whole (Wade et al., 2014; Arslan & Yazıcı, 2021). However; psychosocial care can be neglected in ICUs. Because critically ill cardiac patients may experience communication difficulties due to disorientation, sensory input problems, changes in consciousness due to problems such as intensive care syndrome, delirium, and interventions such as intubation or tracheostomy, and nurses may not have enough time for patients due to their busy work (Happ et al., 2014; Arslan & Yazıcı, 2021).

To minimise such inadvertent adverse effect of ICU environment, NABH (National Accreditation Board for Hospitals, 2012) and SCCM (Society of Critical Care Medicine) (Thompson et al., 2012) provide guidelines and set standards for hospitals to ensure holistic care for patients. These guidelines highlights to integrate psychosocial care into patient care in ICUs (Hariharan et al., 2015; Chivukula et al., 2017). Psychosocial care is the process of identifying and meeting the cognitive, emotional, social, psychosexual, cultural and spiritual needs of the individual (Legg, 2011; Ventegodt et al., 2016). Psychosocial care includes reassuring, comforting and supportive interventions for the patient (Jasemi et al., 2017). The aim of psychosocial care is to adapt to the diagnosis and treatment of the patient and to manage the psychological reactions they experience in this process (Papathanasiou et al., 2013; Arslan & Yazıcı, 2021). Nursing interventions for the psychosocial needs of critical care patients include applications such as diagnosing and meeting psychological needs, therapeutic communication, giving information, listening, empathy, reassurance and therapeutic touch (Wenham & Pittard, 2009; Karlsson et al., 2021).

Considering the negative impact of ICU stay and the role of psychosocial care in minimizing, if not alleviating, the adverse effects of ICU stay, there is a need for standard scales to assess psychosocial care. However, there are mostly scales available that assess nurses’ competence in holistic care (Albagawi et al., 2017; Asgari et al., 2019; Aydın & Hiçdurmaz, 2019; Taşkıran & Turk, 2023). To the best of our knowledge, no study has been found in Turkey that determines what the psychosocial care needs of critically ill cardiac patients. There is a need to a self-report scale to measure the psychosocial care of patients in ICU. This scale has been used to determine thoughts regarding whether the psychosocial care needs of ICU patients are being met or not. Although the scale does not encompass all aspects of holistic care, it is highly significant due to incorporating patients’ self-reports. Such tools will guide nursing practices in the ICU.

Methods

Study design

This study was a methodological design aimed at developing a psychometric scale and identifying the psychosocial care needs of ICU patients. The study was conducted to test the validity and reliability study of the Intensive Care Unit Psychosocial Care Scale for Turkish society.

Sample and setting

The study was carried out in the cardiovascular surgery clinic of a training and research hospital in the north of Turkey, between April 2019 and April 2021. The study sample consisted of 180 critically ill cardiac patients. The sample size was determined on the basis of the study in which the scale was developed (Hariharan et al., 2015). The inclusion criteria for the study were patients having cardiac surgery, aged between 40 and 75 years, staying in the ICU for at least 2-days and transferred to the clinic, able to communicate verbally. Patients who had vision-hearing problems, could not be communicated due to their physical condition in the postoperative period, had chronic psychological disorders, had hemodynamic complication/s in the ICU were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval

Approval from Nursing Ethics Committee of a university and written permissions from the hospital were obtained for the study. Informed consent was obtained from the participants. The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In addition, written permission was obtained via e-mail from Hariharan and colleagues, who created the scale and conducted the validity and reliability study, in order to adapt it to Turkish language and culture prior to the study.

Instruments

The data were collected using a demographic form for the participants, plus the Intensive Care Unit-Psychosocial Care (ICU-PC) Scale and The Intensive Care Experiences Scale (ICES). The demographic form included the sociodemographic and disease characteristics of the cardiac ICU patients (i.e., age, gender, marital status, profession, chronic disease and surgery history, etc.).

Intensive care unit-psychosocial care (ICU-PC)

The ICU-PC was developed by Hariharan and colleagues in order to evaluate whether the psychosocial care needs of ICU patients are met (Hariharan et al., 2015). ICU patients evaluate whether their psychosocial care needs are met as “1 = Never, 2 = Rarely, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Often, 5 = Always”. Three items (5, 9, 17) in the scale were reverse scored. The scores that can be obtained from the scale are between 18 and 90. A high score indicates that the psychosocial care needs of critical care patients are adequately met. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was reported as 0.86 (Hariharan et al., 2015).

Intensive Care Experiences Scale (ICES)

The scale was developed by Rattray et al. to evaluate the experiences of ICU patients (Rattray et al., 2004). The scale was adapted to Turkish by Demir and colleagues and the Cronbach’s alpha value was found to be 0.79 (Demir et al., 2009). The 5-point likert-type scale consists of 19 items. Nine of these items evaluate the patient’s compliance with the ICU, and the other 10 evaluate the frequency of emotional feelings experienced by the patient. The ICES is scored between 19 and 95. A high score from the scale is evaluated as higher awareness and more positive experiences in the ICU.

Scale translation process

For the study, the language validity of the scale was first examined. The scale was first translated from English to Turkish by the first researcher. In the next stage, it was translated into Turkish by 3 English language instructors who have a good command of English and are native speakers of Turkish. Considering the compatibility of the translated scale with the original text, the most appropriate expressions were selected and a Turkish scale was created. Later, the English translation of the scale was made by a foreign language instructor whose native language is Turkish, without showing the English form of the scale. By comparing the English translation and scale expressions, necessary edits were made to the text and its final version was given.

Content validity

Seven experts were consulted for content validity. The experts consisted of 6 academic nurses who are experts in the field of Surgical Nursing and Psychiatric Nursing and 1 language-expression specialist. Expressions were evaluated between 1 and 4 points (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = highly relevant, and 4 = very relevant) in terms of relevance to the scale and translation into Turkish. Content validity index (CVI) range of the scale expressions was 0.86-1.00 and the total CVI value of the scale was 0.90 in the current study. The CVI value was found to be above 0.80 in the total and item level of the scale, and content validity was ensured (Davis, 1992; Polit & Beck, 2006).

Criterion validity

Concurrent scale validity applied for criterion validity. For this purpose, it is compared with the scores of another scale, which was applied with validity and reliability at the time of measurement (Gélinas et al., 2008). Concurrent scale validity was evaluated using the ICES.

Data collection

Before the interview, the purpose and objectives of the research, the benefits to be obtained from the research, the time spent for the interview were explained to the patient, and verbal and written consents were obtained. Data were collected after admission to the cardiovascular surgery clinic after ICU stay.

Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 and AMOS V 24.0 statistical package programs were used to analyze the study data. CVI (Davis technique) was used in determining content validity of the scale. Confirmatory factor analysis-fit indices, CMIN/DF (\({x}^{2}/df\)), goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), incremental fit index (IFI), Tucker Lewis index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) and convergent validity (AVE value) were used to analyze construct validity and evaluation of model fit. The internal consistency reliability was evaluated with the alpha coefficient, combined confidence (CR value) and intra-class correlation coefficient. Pearson correlation coefficient between the ICU-PC scale and the ICES was used to assess concurrent scale validity.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Of the 180 patients in the study, 66.1% were male, 76.1% married, 34.4% literate, 33.3% housewives, 46.7% in the 61–75 age group, and their mean age was 65.96 ± 15.46 years. Among all patients, 17.8% had a history of hypertension, 61.7% no previous surgery, 68.3% stayed in the ICU for the first time, and 32.2% was treated in the ICU for 3 days (Table 1).

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA)

CFA was applied to confirm the 3-dimensional and 14-item structure of the scale. Items 1-2-3-4-5-6 in the scale were statistically significant assigned to Factor 1 with a regression value range of 0.286–0.840; items 7-8-9-10-11-13 on Factor 2 with a regression value range of 0.655–0.790 and items 12–14 on Factor 3 with a regression value range of 0.295–1.107 (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

The model structure with 3 dimensions-14 items, which was established in accordance with the structure of the original scale, was tried. The fit indices of the scale were found to be χ2 = 89.24, df = 52, χ2/df = 1.716, GFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.97, IFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05, SRMR = 0.05. Modifications between items 1 and 4 were applied for this model structure. After CFA, it was determined that the fit indices were in the acceptable range and the structure of the scale was confirmed (Table 3; see Fig. 1 flowchart).

Internal reliability

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of ICU-PC scale was 0.87 (Table 4). Cronbach’s alpha of the third factors were found to be 0.76 (Factor 1), 0.88 (Factor 2) and 0.47 (Factor 3). The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of the ICU-PC scale was also found to be significant and at the level of r = 0.861 (95%CI = 0.829–0.889) (p < 0.001). At the sub-dimension level, 0.742 (Factor 1), 0.871 (Factor 2), and 0.455 (Factor 3) were found to be significant, respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Composite reliability (CR)

It is recommended to calculate the CR value as well as the Cronbach alpha value for the construct reliability. The CR values of the ICU-PC scale were found to be 0.87 (Factor 1), 0.96 (Factor 2) and 0.74 (Factor 3). The total CR value of the scale was 0.98. It was determined that the CR values of the total scale and sub-dimensions were above the limit value (> 0.60) and the combined reliability of the scale was ensured.

Convergent validity

Average variance extracted (AVE) values of the ICU-PC scale were found to be 0.58 (Factor 1), 0.53 (Factor 2) and 0.66 (Factor 3). The total AVE value of the scale was 0.68. Convergent validity of the ICU-PC scale was satisfactory because the AVE values of the scale total and sub-dimensions were above the cut-off value (> 0.50).

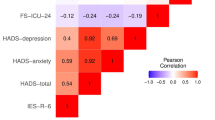

Concurrent validity

A high level, significant and positive correlation was found between the ICU-PC scale and the ICES with a correlation value of r = 0.77 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Research findings showed that the ICU-PC scale met the language, content, construct validity and reliability criteria and could be easily applied to patient individuals. As a result of this study, the original form of the scale was preserved and no changes were made to the elements that make up the scale.

One of the methods used to evaluate construct validity is factor analysis. Factor analysis is a test that aims to define under which sub-dimensions the items in the scale will be grouped. Factor analysis is divided into two as explanatory and confirmatory factor analysis. Only confirmatory factor analysis is sufficient for scale adaptation studies from another language (Burns & Grove, 2009; Harrington, 2009). As a result of the confirmatory factor analysis conducted in this study, it was found that the fit indices were in the acceptable range and the structure of the scale was confirmed (Albright & Park, 2008; Karagöz, 2019). However, confirmatory factor analysis was not tested in the original scale (Hariharan et al., 2015) and the authors stated that construct validity needed to be established by using CFA and this situation constituted a limitation for their study. The study findings demonstrated satisfactory construct validity for the ICU-PC scale. In order for the tested model to be acceptable, the χ2 statistic (p-value) is expected to be non-significant, but in practice it is generally seen to be significant. This is associated with the fact that the χ2 value is very sensitive to sample size. For this reason, the χ2 value is calculated by dividing by the degrees of freedom. The χ2/d.f ratio was found to be 1.716 ≤ 3 in this study and a value of 3 or less indicates that the model is good. A comparative fit index equal to or above 0.90 indicates that there is a good model fit. In this study, CFI was found to be 0.97 and the study has an acceptable model fit. RMSEA represent root mean square error of approximation and RMSEA being equal to or less than 0.08 indicates a good fit (Burns & Grove, 2009; Harrington, 2009). In summary, only CFA was performed since this study was a language adaptation study, and the goodness of fit statistics performed within the scope of CFA were satisfactory.

Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient is calculated to assess whether each item of the scale measures the same attitude within itself in this study. This test is often used when determining the internal consistency of Likert-type scales. (Polit & Beck, 2006; LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2010). The alpha coefficient and ICC values were 0.87 and 0.86, respectively. Accordingly, the reliability level of the ICU-PC scale was found to be high (Ates et al., 2009; Karagöz, 2019). The study findings were consistent with the original scale study that reported that the scale has a high level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.86). Cronbach’s alpha value for ICU-PC scale was 0.86 (Hariharan et al., 2015).

CR and AVE tests were performed to measure convergent validity. Standardized factor loadings of items, AVE values explained by the dimensions in the scale are greater than 0.50, CR coefficients are greater than 0.60, and the CR coefficients also should be greater than the AVE values (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Byrne, 2016; Yaşlıoğlu, 2017). These findings show that the scale adapted to Turkish population meets all these criteria.

In concurrent validity, two equivalent forms are applied simultaneously, continuously, or intermittently at different time intervals. The correlation between forms is calculated and evaluated as a reliability coefficient. Both scales were applied to the study group, and the correlation coefficient between the scores obtained from both tools was calculated. The resulting correlation coefficients were expected to be high (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2010). Thus, the high correlation between the ICU-PC scale and the previously validated ICES show that the scale measures consistently in the current study.

This valid and reliable scale can facilitate researchers and practitioners to quantify the psychosocial care in the ICU (Hariharan et al., 2015). Critical care patients experience psychosocial reactions due to factors such as being at vital risk, inability to communicate, feeling unsafe, lack of privacy, lack of information, prolonged hospitalization, environmental characteristics of ICU, treatment and procedures, physical limitations, and isolation (Hariharan & Chivukula, 2011; Arslan & Yazıcı, 2021). Critical care nurses play an important role in addressing problems and minimizing psychosocial reactions by being aware of the conditions patients experience. It is recognized that in the holistic assessment of patients, in addition to their physiological needs, it is important for nurses to meet their psychosocial needs as well (Wade et al., 2014; Reiss & Sandborn, 2015). In literature, it draws attention to the insufficient awareness among nurses in identifying psychosocial care needs and the various difficulties and barriers encountered in practice (Legg, 2011; Spade et al., 2015). However, psychosocial care is an integral part of nursing care. Diagnostic tools hold a significant place in care, and using objective measurement tools to identify patients’ psychosocial care needs is crucial for integrating psychosocial care into the care of critically ill patients (Legg, 2011; Chivukula et al., 2017). Psychological care practices do not require special time or budget allocation. This can be introduced, integrated, monitored, and measured through regular in-service training sessions aimed at directing and sensitizing staff to patients’ psychosocial needs. A higher level of psychosocial care, requiring only a marginal increase in time allocated to communication, can be cost-effective when assessed for its impact on patient well-being through a holistic approach (Chivukula et al., 2017; Parsons & Walters, 2019).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The study findings were collected through self-report surveys and may introduce response bias. Second, since there was only English version of the ICU-PC scale, comparisons could only be made between the Turkish and English versions of the scale in terms of construct validity.

Conclusion

The ICU-PC scale is a valid, reliable and distinctive scale in assessing the psychosocial care of critically ill cardiac patients. Furthermore, the ICU-PC scale, which consists of 14 items and 3 factors — transparency for decision making and care continuity, protection of human dignity and rights, sustained patient, family orientation — is easy to use. It is recommended that the validity and reliability of the scale be repeated over time, taking into account the changes that may occur as a result of technological, social and cultural developments and changes. Further research could explore its utility across diverse patient populations and healthcare settings for comprehensive validation. Furthermore, ICUs — the latest technology and devices are used to improve the quality of life in critical patient care — are seen as environments that evoke sad feelings and emotions by the patients and their families. In this respect, it is recommended that ICU nurses use the current scale in patient care to integrate psychosocial care into the care of critically ill patients who mostly need these interventions.

Data availability

The data are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Albaqawi, H. M., Butcon, V. R., & Molina, R. R. (2017). Awareness of holistic care practices by intensive care nurses in north-western Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal, 38(8), 826. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2017.8.20056

Albright, J. J., & Park, H. M. (2008). Confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS, LISREL, Mplus and SAS/STAT CALIS. Technical working paper, Indiana University.

Almerud, S., Alapack, R. J., Fridlund, B., & Ekebergh, M. (2008). Caught in an artificial split: A phenomenological study of being a caregiver in the technologically intense environment. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 24(2), 130–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2007.08.003

Arslan, Y., & Yazıcı, G. (2021). Psychosocial care approach of intensive care nurses and the role of consultation-liaison psychiatric nursing. Turkish Journal of Health Research, 2(2), 29–35.

Asgari, Z., Pahlavanzadeh, S., Alimohammadi, N., & Alijanpour, S. (2019). Quality of holistic nursing care from critical care nurses’ point of view. Journal of Critical Care Nursing, 12(1), 9–14.

Ates, C., Öztuna, D., & Genç, Y. (2009). The use of intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in medical research. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Biostatistics, 1(2), 59–64.

Aydin, A., & Hiçdurmaz, D. (2019). Holistic nursing competence scale: Turkish translation and psychometric testing. International Nursing Review, 66(3), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12514

Berthelsen, P. G., & Cronqvist, M. (2003). The first intensive care unit in the world: Copenhagen 1953. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 47(10), 1190–1195. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1399-6576.2003.00256.x

Booker, K. J. (2015). Critical care nursing monitoring and treatment for advanced nursing practice. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Burns, N., & Grove, S. K. (2009). The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis and generation of evidence. Saunders Elsevier, Maryland Heights.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

Chivukula, U., Hariharan, M., Rana, S., Thomas, M., & Andrew, A. (2017). Enhancing hospital well-being and minimizing intensive care unit trauma: Cushioning effects of psychosocial care. Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 21(10), 640. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_468_14

Davis, L. L. (1992). Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied Nursing Research, 5(4), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0897-1897(05)80008-4

Demir, Y., Akın, E., Eşer, I., & Khorshid, L. (2009). Reliability and validity study of the intensive care experience scale. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Nursing Sciences, 1(1), 1–11.

Di Gangi, S., Naretto, G., Cravero, N., & Livigni, S. (2013). A narrative-based study on communication by family members in intensive care unit. Journal of Critical Care, 28(4), 483–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.11.001

Galazzi, A., Adamini, I., Bazzano, G., Cancelli, L., Fridh, I., Laquintana, D., Lusignani, M., & Rasero, L. (2021). Intensive care unit diaries to help bereaved family members in their grieving process: A systematic review. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 68, 103121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103121

Gélinas, C., Loiselle, C. G., LeMay, S., Ranger, M., Bouchard, E., & McCormack, D. (2008). Theoretical, psychometric and pragmatic issues in pain measurement. Pain Management Nursing, 9(3), 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2007.12.001

Happ, M. B., Garrett, K. L., Tate, J. A., DiVirgilio, D., Houze, M. P., Demirci, J. R., George, E., & Sereika, S. M. (2014). Effect of a multi-level intervention on nurse–patient communication in the intensive care unit: Results of the SPEACS trial. Heart & Lung, 43(2), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.010

Hariharan, M., & Chivukula, U. (2011). Patient care in Intensive Care units (ICUs): Biopsychosocial assessment. Journal of Indian Health Psychology, 5(2), 25–35.

Hariharan, M., Chivukula, U., & Rana, S. (2015). The intensive care unit psychosocial care scale: Development and initial validation. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 31(6), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2015.06.003

Harrington, D. (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis. Oxford University Press.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jasemi, M., Valizadeh, L., Zamanzadeh, V., & Keogh, B. (2017). A concept analysis of holistic care by hybrid model. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 23(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.197960

Karagöz, Y. (2019). SPSS-AMOS-META applied statistical analysis. Nobel Academic Publishing, Ankara.

Karlsson, L., Rosenqvist, J., Airosa, F., Henricson, M., Karlsson, A. C., & Elmqvist, C. (2021). The meaning of caring touch for healthcare professionals in an intensive care unit: A qualitative interview study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 68, 103131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103131

Legg, M. J. (2011). What is psychosocial care and how can nurses better provide it to adult oncology patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28(3), 61–67.

LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2010). Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice. Mosby Louis.

National Aaccreditation Board for Hospitals & Healthcare Providers, NABH Accredited Hospitals (2012). http://www.nabh.co/main/hospitals/accredited.asp

Papathanasiou, I., Sklavou, M., & Kourkouta, L. (2013). Holistic nursing care: Theories and perspectives. The American Journal of Nursing, 2(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajns.20130201.11

Parsons, L. C., & Walters, M. A. (2019). Management strategies in the intensive care unit to improve psychosocial outcomes. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 31(4), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnc.2019.07.009

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20147

Rattray, J., Johnston, M., & Wildsmith, J. A. (2004). The intensive care experience: Development of the ICE questionnaire. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03066.x

Reiss, M., & Sandborn, W. J. (2015). The role of psychosocial care in adapting to health care reform. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 13(13), 2219–2224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.010

Spade, C. M., Fitzsimmons, K., & Houser, J. (2015). Reliability testing of the psychosocial vital signs assessment tool. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 53(11), 39–45.

Taşkıran, N., & Turk, G. (2023). The relationship between the ethical attitudes and holistic competence levels of intensive care nurses: A cross-sectional study. PloS ONE, 18(7), e0287648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287648

Thompson, D. R., Hamilton, D. K., Cadenhead, C. D., Swoboda, S. M., Schwindel, S. M., Anderson, D. C., Schmitz, E. V., Andre, S., Axon, A. C., Harrell, D. C., Harvey, J. W., Howard, M. A., Kaufman, A., D. C., & Petersen, C. (2012). Guidelines for intensive care unit design. Critical Care Medicine, 40(5), 1586–1600. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182413bb2

Ventegodt, S., Kandel, I., Ervin, D. A., & Merrick, J. (2016). Concepts of holistic care. In I. L. Rubin (Ed.), Health care for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the lifespan (pp. 1935–1941). Springer, Switzerland.

Wade, D. M., Hankins, M., Smyth, D. A., Rhone, E. E., Mythen, M. G., Howell, D. C., & Weinman, J. A. (2014). Detecting acute distress and risk of future psychological morbidity in critically ill patients: Validation of the intensive care psychological assessment tool. Critical Care, 18(5), 519. http://ccforum.com/content/18/5/519

Wenham, T., & Pittard, A. (2009). Intensive care unit environment. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia. Critical Care & Pain, 9(6), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkp036

Yaşlıoğlu, M. M. (2017). Factor analysis and validity in social sciences: Application of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. Istanbul University Journal of the School of Business, 46, 74–85. http://dergipark.ulakbim.gov.tr/iuisletme

Zamanzadeh, V., Jasemi, M., Valizadeh, L., Keogh, B., & Taleghani, F. (2015). Effective factors in providing holistic care: A qualitative study. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 21(2), 214. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1075.156506

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank critically ill cardiac patients in the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). The author(s) received no financial support for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics statement

All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee of a university. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yaman Aktaş, Y., Karabulut, N. The intensive care unit psychosocial care scale: validity and reliability study in cardiac surgery patients. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06298-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06298-6