Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many regions and countries implemented lockdowns and isolation to curb the virus’s spread, which might increase loneliness and lead to a series of psychological distress. This study aims to investigate the association between loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and examine whether perceived social support and perceived internal control mediate the loneliness-depression relationship in China. Self-report questionnaires were distributed online in two waves during the pandemic in 2020. At Wave 1, demographics and loneliness were reported when the lockdown was initially implemented in China, and at Wave 2, as the pandemic came under control and the epicenter lifted its lockdown. Depression, perceived social support, and perceived internal control were measured at both two waves. Higher levels of loneliness at Wave 1 were associated with more depression at Wave 2 after controlling for baseline depression and demographic variables. Simple mediation models showed that both perceived social support and internal control at two waves independently mediated the relationship between Wave 1 loneliness and Wave 2 depression. Additionally, the serial multiple mediation model indicated that perceived social support and perceived internal control sequentially mediated the path from loneliness to subsequent depression. A higher level of loneliness during the initial lockdown was linked with more severe depression with the development of the COVID-19 pandemic. Both perceived social support and perceived internal control acted as essential protective factors against depression from loneliness. Meanwhile, social support might protect mental health by enhancing the sense of self-control when facing loneliness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) developed into a global pandemic since December 2019. Since then, governments announced and reinforced quarantine or lockdowns in many regions. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a threat to the physical and mental health of the general population (Duan et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021). The increased level of loneliness was widespread during the lockdown (Beam & Kim, 2020), which in turn was associated with worse physical and psychological well-being (Maes et al., 2019). Additionally, depression has emerged as a public health issue before and during the pandemic (Park et al., 2019). This study aims to investigate the association between loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and examine whether perceived social support and perceived internal control mediate the loneliness-depression relationship.

Loneliness and mental health

Loneliness is defined as an unpleasant experience perceived by an individual due to the insufficient quality and quantity of social relationship networks (Perlman & Peplau, 1981). Loneliness has become a growing problem in modern society (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2018). For instance, the prevalence of loneliness among the elderly in China has shown a dramatically rising trend (Luo & Waite, 2014). A national survey in Switzerland has also found that about 40% of the 20,007 respondents have felt lonely (Richard et al., 2017). After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, 43% of participants reported moderate to severe levels of loneliness, and more than 60% frequently felt “being separated from society” (Killgore et al., 2020).

Loneliness has shown an adverse influence on human health, both mentally and physically. For example, lonely individuals exhibited a reduction in prosocial behavior (Twenge et al., 2007), more symptoms of social anxiety (Maes et al., 2019), and a higher prevalence of suicide ideation (Stravynski & Boyer, 2001). Furthermore, feeling lonely is one of the typical features of depressive symptoms (Erzen & Çikrikci, 2018). Extensive studies have shown that loneliness is an essential predictor of depression, such that a higher score of loneliness is associated with more severe depressive symptoms in older people (Liu et al., 2016), adolescents (Ladd & Ettekal, 2013) as well as among the general population (Rossi et al., 2020). An 8-year follow-up study has demonstrated that chronic loneliness in childhood increased individuals’ susceptibility to depression in adolescence (Qualter et al., 2010). A longitudinal study revealed that the elderly who feel lonelier are more likely to develop major depression disorders and general anxiety disorders in two years (Domènech-Abella et al., 2019). Specifically, loneliness positively predicted depression among the general population in Israel during the COVID-19 pandemic (Palgi et al., 2020) and older adults in the United States (Krendl & Perry, 2020). However, few studies have investigated the potential risk or protective factors in the loneliness-depression correlation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In stress and adaptation literature, the impact of people’s resources plays a vital role in stress resistance and resiliency (Hobfoll, 1989, 2002). Psychological resources are described as entities or means to obtain valued ends and include social and personal aspects. i.e., the external social environment and the self (Hobfoll, 2002). Caplan (1974) pointed out that social support and a sense of mastery were two critical elements for maintaining well-being. As most frequently discussed, social support and perceived control appear to be the central elements of social and personal resources, respectively (Taylor & Stanton, 2007). Social support and perceived control have consistently shown adaptive values in dealing with stressful situations (e.g., violence or cancer) (Bebanic et al., 2017; Helgeson et al., 2004). Here, this study aims to examine the role of psychological resources, including perceived social support and perceived control, in the loneliness-depression relationship during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Social resource: role of perceived social support

Social support refers to an essential coping resource or assistance from friends, family, or significant others under stressful situations (e.g., the COVID-19 outbreak) (Sarason et al., 1983; Zimet et al., 1988). There are two potential dimensions of social support: the actual size of one’s social support system and the subjective assessment of social support provided by the system (Sarason et al., 1983). Studies have provided consistent evidence that perceived social support is a solid and positive indicator of individuals’ well-being (Karademas, 2006) and life satisfaction (Siedlecki et al., 2014).

As a crucial coping mechanism under challenges, social support has also been demonstrated to protect psychological health during the COVID-19 pandemic (Saltzman et al., 2020). The value of social support seemed particularly relevant to loneliness due to the lockdown and related measures such as quarantine and social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic. First, perceived social support was well-documented as one of the most crucial protective factors against loneliness (Lasgaard et al., 2010). Second, numerous studies have also revealed the buffering role of social support on symptoms of depression (Duan et al., 2020) and anxiety (Yue et al., 2020). Therefore, perceived social support, as a core element of social resources, might alleviate depression resulting from loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Personal resource: role of perceived internal control

Perceived control is frequently discussed in conjunction with stressful life events, in which events perceived as uncontrollable are more distressing than those perceived as controllable (Foa et al., 1992). According to Skinner (1995), experiencing control is an innate and universal need for individuals to facilitate interactions with their environment. A lack of perceived control can result in learned helplessness, which is considered one of the main characteristics of depression (Rubinstein, 2004). More perceptions of control might help individuals regulate their emotions and behaviors, especially under challenges or threats (Skinner, 1995), manifesting in lower levels of loneliness (Andrew & Meeks, 2018), depression (Gallagher & McKinley, 2009), and anxiety (Gallagher et al., 2014).

It is worthwhile to mention that external control of events or outcomes might not be feasible for many situations like the current public health emergency (i.e., the COVID-19 pandemic), while perceived control over internal personal states like emotions and thoughts appears to be more critical and practical for adaptation under adverse or threatening circumstances (Pallant, 2000). For instance, participants showed decreased external control over the infection with the development of the COVID-19 pandemic, which further resulted in irrational behaviors like stocking up on food (Goodwin et al., 2021). By contrast, an earlier study with cancer patients found that perceived control over internal states, such as emotional and physical responses to disease, instead of control over the disease course per se, predicted better overall psychological adjustments, including fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (Thompson et al., 1993). Hence, under the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, higher perceived internal control as an essential personal resource may reduce loneliness-related depression, i.e., more perceptions of internal control might buffer the association between loneliness and depression.

A serial multiple mediation model

Based on the brief literature review above, this study aims to investigate the mediating effects of perceived social support and perceived internal control in the association between loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, perceived social support and perceived internal control might not act independently, as social resources are reciprocally interrelated to personal resources (Hobfoll et al., 1990). For instance, a nine-year longitudinal study found that perceived control acted as both an antecedent and an outcome of social support (Gerstorf et al., 2011). This finding aligns with earlier propositions that social support can exert positive effects by promoting a sense of self-control in the face of adverse events (Cohen & Wills, 1985; Hobfoll, 1989). Therefore, a serial multiple mediation model was proposed in our study to explore whether perceived social support and perceived internal control work together in the loneliness-depression relation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The present study

We aimed to examine the following hypotheses:

-

1)

Loneliness at Wave 1 would be positively associated with depression at Wave 2.

-

2)

Perceived social support and perceived internal control would mediate the relationship between loneliness at Wave 1 and depression at Wave 2, respectively.

-

3)

Perceived social support and perceived internal control would sequentially mediate the path from Wave 1 loneliness to Wave 2 depression. Specifically, in a serial way, higher levels of loneliness at Wave 1 would be linked to lower levels of perceived social support and perceived internal control at Wave 1, which would be related to greater depression at Wave 2.

Methods

Participants and procedures

The present study was part of a big project (Duan et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2021), and included data collection in two waves: from January 31st to February 9th (Wave 1) and from March 15th to March 28th (Wave 2) in 2020, covering the period from the initial lockdown to when the restrictions were lifted in China (Ren, 2020). Questionnaires were administered using WenJuanXing (an online survey tool developed by Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Hunan, China). We commissioned WenJuanXing to recruit participants randomly from their user database in China, and participants were compensated separately with monetary incentives for their participation in the two waves of the survey. Ethical approval was provided by the ethics committee at the local university.

Six infrequent items (e.g., “I do not remember my name”) were used to identify invalid respondents for the attention checks for online research (Newman et al., 2021). Participants with at least four correct answers to attention checks were included in the final analyses. At the first wave, 5,019 respondents were contacted and 3,206 met the inclusion criteria above, resulting in a compliance rate of 63.88%. Among these 3,206 participants, 1,390 completed all questionnaires in Wave 2, yielding a compliance rate of 43.36%Footnote 1. Therefore, data from these 1,390 individuals were analyzed in the current study and the demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. 403 participants in the final sample were from Hubei Province, and others were from the 29 provinces and regions in mainland China.

Measures

Loneliness

The UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) Loneliness Scale (ULS), developed by Russell et al. (1980), was used to measure loneliness levels for its wide application in other studies under the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Alheneidi et al.,2021). Zhou and colleagues (2012) translated these items into Chinese and demonstrated good psychometric properties in the revised 6-item version (i.e., ULS-6). ULS-6 is a unidimensional scale rated from 1 (never) to 5 (all the time), and an exemplary item is “There is no one I can turn to”. Participants rated their loneliness levels at Wave 1. Cronbach’s alpha of ULS-6 for the present study was 0.745.

Depression

The Psychological Questionnaire for Emergent Events of Public Health was used to measure depression in two waves, and this scale has been commonly applied to assess psychological states within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic recently (e.g., Zhou et al., 2021). This scale was revised from the SARS Psychological Behaviour Questionnaire (Gao et al., 2004) and its dimension of depression includes six items. Each item was scored on a 4-point Likert scale, such as “My appetite was poor” or “I have no energy for things”. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.809 and 0.803 at Wave 1 and Wave 2, respectively.

Perceived social support

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) measured respondents’ subjective understanding and feeling of social support (Zimet et al., 1988) in Wave 1 and Wave 2. The Chinese version of the PSSS was translated and validated by Jiang (2001). Participants responded via a 7-point Likert self-report scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating a higher degree of perceived social support. For instance, “I can talk about my problems with my friends”. The internal consistency coefficients were 0.812 and 0.828 at Wave 1 and 2, respectively.

Perceived internal control

Perceived internal control was measured using the Perceived Control of Internal States Scale (PCISS; Pallant, 2000). There are 18 items, and each item is rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An exemplary item is “I am usually able to keep my thoughts under control”. Higher scores were indicative of more perceptions of control over internal states. Respondents rated according to their current and actual situations. Cronbach alpha coefficients for PCISS were 0.915 and 0.925 at Wave 1 and Wave 2.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Each scale was generated from the average of total scores. Age was coded as continuous variables, gender was coded as the binary variable, and education and monthly income were coded as ordinal variables (see Supplemental Table S1 for variables’ codes and response categories). All the continuous variables were standardized for the subsequent analyses. All analyses regarded a two-tailed significance level < 0.05 as statistically significant.

First, the paired t-test was used to compare depression, perceived social support, and perceived internal control across the two surveys (Wave 1 vs. Wave 2). Meanwhile, correlation analyses were conducted to explore the potential relationships among variables. Then, simple mediation models using Model 4 from PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2017) were built to test the mediating effects of perceived social support or perceived internal control on the association between Wave 1 loneliness and Wave 2 depression. Finally, a multiple mediation model was conducted using Model 6 to examine whether perceived social support and perceived internal control mediate the loneliness-depression relation sequentially. The indirect effect was produced using the percentile bootstrap with 5,000 samples to generate 95% confidence intervals for the mediated paths (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). Confidence intervals that do not include zero indicate significant effects. The effect size for the mediation analysis was quantified as the relative mediation effect (PM = a*b/c) for the indirect effect (Preacher & Kelley, 2011). The standard error for linear regression models was estimated using HC3 (Davidson & MacKinnon, 1993) to keep the test size at the nominal level regardless of heteroscedasticity (Long & Ervin, 2000).

Results

Comparison analyses

Perceived social support showed a statistically significant increase from Wave 1 to Wave 2 (t = -8.607, p < .001; Wave 1: 5.54 ± 0.73; Wave 2: 5.69 ± 0.68), while the levels of perceived internal control did not show statistically significant changes between the two waves (t = -1.510, p = .131; Wave 1: 3.61 ± 0.61; Wave 2: 3.63 ± 0.63). Furthermore, there was a statistically significant increase (t = -3.362, p = .001) in depression levels from Wave 1 (1.56 ± 0.51) to Wave 2 (1.60 ± 0.52).

Correlation analyses

Loneliness at Wave 1 was positively associated with depression both at wave 1 (r = .356, p < .001) and Wave 2 (r = 320, p < .001) (see Supplemental Table S2). Perceived social support (Wave 1: r = − .210, p < .001; Wave 2: r = − .240, p < .001) and perceived internal control at two waves (Wave 1: r = − .323, p < .001; Wave 2: r = − .418, p < .001) were negatively related to depression at Wave 2 (see Supplemental Table S2).

Mediation analyses

The mediating role of perceived social support

Perceived social support at Wave 1 was treated as a mediator between Wave 1 loneliness and Wave 2 depression2, controlling for Wave 1 depression and demographic variables (gender, age, education, and monthly income). Results showed that there was a statistically significant direct effect between loneliness and depression (Path c: β = .132, 95% CI = [.075,.189], p < .001). This association kept significant after taking Wave 1 perceived social support into the model (Path c’: β = 0.105, 95% CI = [0.045, 0.165], p < .001). The indirect effect of loneliness on depression through perceived social support was statistically significant (a*b = 0.026, 95% CI = [0.007, 046]) and accounted for 19.70% of the total effect.

The mediating role of perceived internal control

Similarly, when Wave 1 perceived internal control served as the mediatorFootnote 2, there was still a statistically significant direct effect of loneliness on depression (Path c’: β = 0.092, 95% CI= [0.033, 0.151], p = .002) and the indirect path was significant (a*b = 0.040, 95% CI = [0.017, 064]). Additionally, perceived internal control explained 30.30% of the total effect of loneliness on depression.

The serial multiple mediation model

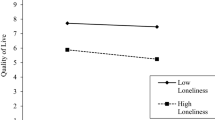

As shown in Table 2; Fig. 1, the multiple mediations showed three indirect paths from Wave 1 loneliness to Wave 2 depression. First, Path 1 (loneliness → perceived social support → depression) was not statistically significant (a*b = 0.016, 95% CI = [-0.005, 0.037]). Second, Path 2 (loneliness → perceived internal control → depression) was statistically significant, and the indirect effect explained for 16.67% of the total effect (a*b = 0.022, 95% CI = [0.006, 0.041]). Third, Path 3 (loneliness → perceived social support → perceived internal control → depression) was also statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.011, 95% CI = = [0.003, 0.019]) and the proportion of this indirect path was 8.33%. Therefore, perceived social support and perceived internal control at Wave 1 sequentially mediated the relationship between loneliness and depressionFootnote 3.

The serial multiple mediation model of the relationship between Wave 1 loneliness and Wave 2 depression through Wave 1 perceived social support and perceived internal control sequentially. Standardized regression coefficients are shown along the paths (***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05). Solid lines are statistically significant, and the dotted line is not significant

Discussion

This study aims to explore the impact of loneliness on depression and the potential mediating roles of perceived social support and perceived internal control in the loneliness-depression link during the COVID-19 pandemic. As hypothesized, higher levels of loneliness at Wave 1 were associated with increased depression at Wave 2 after adjusting for baseline depression and demographic variables. Simple mediation models showed significant and independent indirect effects of perceived social support and perceived internal control (both in Wave 1 and Wave 2) on the loneliness-depression association. Furthermore, the serial multiple mediation model indicated that perceived social support and perceived internal control sequentially mediated the relationship between loneliness and depression.

When comparing Wave 1 and Wave 2, we found that perceived social support significantly increased, which might come from the increasing social support from neighborhoods and satisfaction with the performance of the central government (e.g., quick medical supplies and policy responses) (Chen et al., 2020). In contrast, depression deteriorated from the initial lockdown (Wave 1) to the relative remission phase (Wave 2), suggesting a lasting and severe psychological burden of the pandemic (Duan et al., 2020; Meaklim et al., 2021). Additionally, the perceived internal control did not change significantly across the two surveys, confirming the relative stability of perceived control (e.g., You et al., 2011).

We found that the higher level of loneliness during the initial lockdown phase was related to higher levels of depression during the relative remission phase, even after controlling for the initial depression symptoms. This result was further consistent with previous literature conducted in a large community-based cohort study (Beutel et al., 2017) or among the general population from different countries during the COVID-19 pandemic (Okruszek et al., 2020; Palgi et al., 2020). Insufficient social connections during the lockdown and social distancing as a preventive measurement for infection might be the main contributors to loneliness during the pandemic (Beam & Kim, 2020; Miller, 2020). In turn, these measurements might result in the generation of social anhedonia (Barkus & Badcock, 2019). Furthermore, studies also found that loneliness is closely linked to the inflammatory reactivity of stress, a crucial marker for future depressive symptoms (Aschbacher et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2018).

Subjective perception of social support as an essential social resource could account for the relationship between loneliness and subsequent depression. Specifically, higher levels of perceived social support can buffer the adverse effects of loneliness on depression. As a critical psychological resource, perceived social support has been proven effective in buffering against loneliness (Lee & Goldstein, 2016). According to the theory of the self-reinforcing loneliness loop, lonely individuals tend to exhibit more negative social expectations and further distance themselves from social partners to avoid possible social threats like social rejection (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Therefore, this study revealed that higher levels of perceived social support could protect mental health in stressful or threatening situations (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) by breaking or weakening the self-reinforcing loneliness loop. Conversely, the lack of social support may increase hopelessness and eventually lead to depression (Abramson et al., 1989), i.e., enhancing the self-reinforcing loneliness loop.

Perceived internal control was another significant mediator in the indirect path of loneliness to depression during the lockdown. This might indicate that lonely individuals report less emotional control over their emotions and behaviors during the pandemic, and lower internal control ultimately aggravates depression. This result was consistent with Newall and colleagues’ findings (2014) that persistent lonely people tend to experience lower perceptions of control than the rarely lonely group, and the decline of perceived control is a risk factor for increased loneliness in the future. First, consistent with the previous finding (Zhao & Shi, 2020), the current study supported that higher levels of loneliness were associated with fewer perceptions of internal control in the face of the uncontrollable pandemic. The loneliness model also proposed that loneliness may elicit implicit vigilance for social threats and thereby dampen self-regulation over one’s thoughts, feelings, and behavior (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). Second, we found that lower perceived internal control is linked with subsequent more severe depression. A similar result was also revealed in the prospective study in maltreated children that adequate perceived internal control predicted decreased internalizing problems like anxiety and depression (Bolger & Patterson, 2001). When exposed to uncontrollable circumstances (e.g., pandemic or cancer diagnosis), individuals with better control over internal states (emotions, thoughts, etc.) may exhibit fewer negative appraisals of the adverse situations and take more adaptive coping strategies like social interactions, further leading to better psychological adjustment later (Henselmans, 2009).

Based on the association between perceived social support and perceived internal control, the current study also tested the serial multiple mediation model and found that perceived social support and perceived internal control mediated the relationship between loneliness and depression in a sequential way. Specifically, participants with lower levels of loneliness might be inclined to perceive more social support, and high perceived social support further enhances the perception of internal control, thereby decreasing depression levels during the pandemic. According to the support-efficacy model, received and perceived support can stimulate the generation of self-efficacy (a related concept with perceived control) by developing a positive sense of self, consequently leading to better well-being (Antonucci & Jackson, 1987). Therefore, social resources (i.e., social support) can be translated into personal resources (i.e., self-control or efficacy). For example, Gerstorf et al. (2011) found that a supportive relationship with family contributed to higher subjective control and increased perceived control. Furthermore, in addition to the positive effect of perceived social support on perceived internal control, our finding further highlighted this synergy in reducing loneliness-related depression. This echoed the integrated resources model that social and personal resources must work together to help individuals cope with threats or challenges (Holahan et al., 1999). Nonetheless, the multiple mediation model showed that perceived internal control, but not social support could independently mediate the path from loneliness to depression (path 1 and path 2). Altogether, these results suggested that the effect of subjective social support, to some extent, might be limited when facing adverse situations but instead could serve as a more robust buffer when these social resources are internalized into personal resources.

The current study had several limitations. First, the survey used online convenience sampling in China, which limited its ecological validity in methodology. There were significant demographic differences between respondents who completed both two waves and respondents who dropped out at Wave 2, suggesting that these demographic variables might bias our results. Second, all questionnaires were self-reported, which participants might underreport, or overestimate based on their current state. However, it is worthwhile to mention that self-report is the most effective method within public mental health services and research (Bentley et al., 2019), and all the questionnaires we used are standard and valid. Third, this longitudinal study collected data only at two waves and might not be able to sketch the dynamic mental health trajectories with the evolution of the pandemic. Nonetheless, this study captured the critical moments, covering the period from the initial lockdown to when the epicenter lifted its lockdown. Last, the current study is implemented within the background of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak, and future studies need to explore whether these findings are repeatable during a “normal” time.

Despite the limitations above, this research also provided some implications. Depression demonstrated a slight increase even when the COVID-19 pandemic was under a certain degree of control, indicating the importance of mental health services in the general population when facing emergent public events. Considering that higher levels of loneliness may increase the risk of future depression, it might be crucial to screen the population susceptible to psychopathology at the early stage of such pandemics. Perceived social support and perceived control are essential protective factors against depression from loneliness. Some potential interventions might be practical to alleviate the feeling of loneliness and loneliness-derived mental health problems. For instance, cognitive intervention research demonstrated that social network enhancement could mitigate depression and loneliness and improve life quality (Winningham & Pike, 2007). Mindfulness has also been shown to be effective in helping individuals experience more control and well-being by boosting flexible responses to the environment’s demands (Smith & Neupert, 2020). Additionally, external social support may be a potential intervention target for enhancing personal resources such as perceived internal control.

Conclusions

Higher loneliness was associated with more depression symptoms. Both perceived internal control and perceived social support acted as essential protective factors against depression from loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, social support can exert positive effects when facing loneliness by enhancing the sense of self-control.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

We divided the Wave 1 valid participants (n = 3,206) into respondents (n = 1,390) and non-respondents (n = 1,816) in terms of whether they participated in Wave 2, and we further compared the difference of demographic variables (age, gender, education, and monthly income) between the two groups. Results showed significant demographic differences including age, gender, education, and monthly income between the two groups (see Supplemental Table S1 for details).

We also conducted two simple mediation models between loneliness and depression using Wave 2 perceived social support and perceived control as mediators, respectively. Results showed significant indirect paths of both perceived social support and perceived control at Wave 2 on the association between Wave 1 loneliness and Wave 2 depression (see Supplemental Table S3 for details).

We also conducted Furthermore, we also tested the serial multiple mediation model in the relationship between loneliness and depression when Wave 2 perceived social support and perceived control served as the mediators successively. Similarly, results suggested that Path 1 (loneliness → perceived social support → depression) was not significant. There were two significant indirect paths from loneliness to depression: Path 2 (loneliness → perceived internal control → depression) and Path 3 (loneliness → perceived social support → perceived internal control → depression) (see Supplemental Table S4 and Figure S1 for details).

References

Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., & Alloy, L. B. (1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96(2), 358.

Alheneidi, H., AlSumait, L., AlSumait, D., & Smith, A. P. (2021). Loneliness and problematic internet use during COVID-19 lock-down. Behavioral Sciences, 11(1), 5.

Andrew, N., & Meeks, S. (2018). Fulfilled preferences, perceived control, life satisfaction, and loneliness in elderly long-term care residents. Aging & Mental Health, 22(2), 183–189.

Antonucci, T. C., & Jackson, J. S. (1987). Social support, interpersonal efficacy, and health: A life course perspective.

Aschbacher, K., Epel, E., Wolkowitz, O. M., Prather, A. A., Puterman, E., & Dhabhar, F. S. (2012). Maintenance of a positive outlook during acute stress protects against pro-inflammatory reactivity and future depressive symptoms. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 26(2), 346–352.

Barkus, E., & Badcock, J. C. (2019). A transdiagnostic perspective on social anhedonia. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 216.

Beam, C. R., & Kim, A. J. (2020). Psychological sequelae of social isolation and loneliness might be a larger problem in young adults than older adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S58.

Bebanic, V., Clench-Aas, J., Raanaas, R. K., & Nes, B., R (2017). The relationship between violence and psychological distress among men and women: Do sense of mastery and social support matter? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(16), 2371–2395.

Bentley, N., Hartley, S., & Bucci, S. (2019). Systematic review of self-report measures of general mental health and wellbeing in adolescent mental health. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(2), 225–252.

Beutel, M. E., Klein, E. M., Brähler, E., Reiner, I., Jünger, C., Michal, M., & Tibubos, A. N. (2017). Loneliness in the general population: Prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. Bmc Psychiatry, 17(1), 97.

Bolger, K. E., & Patterson, C. J. (2001). Pathways from child maltreatment to internalizing problems: Perceptions of control as mediators and moderators. Development and Psychopathology, 13(4), 913–940.

Brown, E. G., Gallagher, S., & Creaven, A. M. (2018). Loneliness and acute stress reactivity: A systematic review of psychophysiological studies. Psychophysiology, 55(5), e13031.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet, 391(10119), 426.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

Caplan, G. (1974). Support systems and community mental health: Lectures on concept development. behavioral.

Chen, X., Gao, H., Zou, Y., & Lin, F. (2020). Changes in psychological wellbeing, attitude and information-seeking behaviour among people at the epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic: A panel survey of residents in Hubei Province. China Epidemiology & Infection, 148.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310.

Davidson, R., & MacKinnon, J. G. (1993). Estimation and inference in econometrics. OUP Catalogue.

Domènech-Abella, J., Mundó, J., Haro, J. M., & Rubio-Valera, M. (2019). Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from the Irish longitudinal study on Ageing (TILDA). Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 82–88.

Duan, H., Yan, L., Ding, X., Gan, Y., Kohn, N., & Wu, J. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general Chinese population: Changes, predictors and psychosocial correlates. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113396.

Erzen, E., & Çikrikci, Ö. (2018). The effect of loneliness on depression: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(5), 427–435.

Foa, E. B., Zinbarg, R., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1992). Uncontrollability and unpredictability in post-traumatic stress disorder: An animal model. Psychological Bulletin, 112(2), 218.

Gallagher, M. W., Bentley, K. H., & Barlow, D. H. (2014). Perceived control and vulnerability to anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38(6), 571–584.

Gallagher, R., & McKinley, S. (2009). Anxiety, depression and perceived control in patients having coronary artery bypass grafts. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65(11), 2386–2396.

Gao, Y., Xu, M., Yang, Y., & Yao, K. (2004). Discussion on the coping style of undergraduates and the correlative factors during the epidemic period of SARS. Chinese Medical Ethics, 17(2), 60–63.

Gerstorf, D., Röcke, C., & Lachman, M. E. (2011). Antecedent–consequent relations of perceived control to health and social support: Longitudinal evidence for between-domain associations across adulthood. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(1), 61–71.

Goodwin, R., Wiwattanapantuwong, J., Tuicomepee, A., Suttiwan, P., Watakakosol, R., & Ben-Ezra, M. (2021). Anxiety, perceived control and pandemic behaviour in Thailand during COVID-19: Results from a national survey. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 135, 212–217.

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Mmedicine, 40(2), 218–227.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford.

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927.

Helgeson, V. S., Snyder, P., & Seltman, H. (2004). Psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer over 4 years: Identifying distinct trajectories of change. Health Psychology, 23(1), 3.

Henselmans, I. (2009). Psychological Well-being and Perceived Control after a Brest Cancer diagnosis. University Library Groningen.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324.

Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J., Lane, C., & Geller, P. (1990). Conservation of social resources: Social support resource theory. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(4), 465–478.

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., & Cronkite, R. C. (1999). Resource loss, resource gain, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 620.

Jiang, Q. (2001). Perceived social support scale. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medicine and Brain Science, 10(10), 41–43.

Karademas, E. C. (2006). Self-efficacy, social support and well-being: The mediating role of optimism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1281–1290.

Killgore, W. D., Cloonen, S. A., Taylor, E. C., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 113117.

Krendl, A. C., & Perry, B. L. (2020). The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences.

Ladd, G. W., & Ettekal, I. (2013). Peer-related loneliness across early to late adolescence: Normative trends, intra-individual trajectories, and links with depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1269–1282.

Lasgaard, M., Nielsen, A., Eriksen, M. E., & Goossens, L. (2010). Loneliness and social support in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 218–226.

Lee, C. Y. S., & Goldstein, S. E. (2016). Loneliness, stress, and social support in young adulthood: Does the source of support matter? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 568–580.

Liu, L., Gou, Z., & Zuo, J. (2016). Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 750–758.

Long, J. S., & Ervin, L. H. (2000). Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. The American Statistician, 54(3), 217–224.

Luo, Y., & Waite, L. J. (2014). Loneliness and mortality among older adults in China. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(4), 633–645.

Maes, M., Nelemans, S. A., Danneel, S., Fernández-Castilla, B., Van den Noortgate, W., Goossens, L., & Vanhalst, J. (2019). Loneliness and social anxiety across childhood and adolescence: Multilevel meta-analyses of cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Developmental Psychology, 55(7), 1548.

Meaklim, H., Junge, M. F., Varma, P., Finck, W. A., & Jackson, M. L. (2021). Pre-existing and post-pandemic insomnia symptoms are associated with high levels of stress, anxiety and depression globally during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, jcsm–9354.

Miller, G. (2020). Social distancing prevents infections, but it can have unintended consequences. Science.

Newall, N. E., Chipperfield, J. G., & Bailis, D. S. (2014). Predicting stability and change in loneliness in later life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 31(3), 335–351.

Newman, A., Bavik, Y. L., Mount, M., & Shao, B. (2021). Data collection via online platforms: Challenges and recommendations for future research. Applied Psychology, 70(3), 1380–1402.

Okruszek, L., Aniszewska-Stańczuk, A., Piejka, A., Wiśniewska, M., & Żurek, K. (2020). Safe but lonely? Loneliness, mental health symptoms and COVID-19.

Palgi, Y., Shrira, A., Ring, L., Bodner, E., Avidor, S., Bergman, Y., & Hoffman, Y. (2020). The loneliness pandemic: Loneliness and other concomitants of depression, anxiety and their comorbidity during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Affective disorders.

Pallant, J. F. (2000). Development and validation of a scale to measure perceived control of internal states. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2), 308–337.

Park, C., Rosenblat, J. D., Brietzke, E., Pan, Z., Lee, Y., Cao, B., & McIntyre, R. S. (2019). Stress, epigenetics and depression: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 102, 139–152.

Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. Personal Relationships, 3, 31–56.

Preacher, K. J., & Kelley, K. (2011). Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods, 16(2), 93.

Qualter, P., Brown, S. L., Munn, P., & Rotenberg, K. J. (2010). Childhood loneliness as a predictor of adolescent depressive symptoms: An 8-year longitudinal study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 19(6), 493–501.

Ren, X. (2020). Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 61(4–5), 423–434.

Richard, A., Rohrmann, S., Vandeleur, C. L., Schmid, M., Barth, J., & Eichholzer, M. (2017). Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: Results from a Swiss national survey. PloS One, 12(7), e0181442.

Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., & Di Lorenzo, G. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 790.

Rubinstein, G. (2004). Locus of control and helplessness: Gender differences among bereaved parents. Death Studies, 28(3), 211–223.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472.

Saltzman, L. Y., Hansel, T. C., & Bordnick, P. S. (2020). Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S55.

Sarason, I. G., Levine, H. M., Basham, R. B., & Sarason, B. R. (1983). Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 127.

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2014). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 561–576.

Skinner, E. A. (1995). Perceived control, motivation, & coping (Vol. 8). Sage.

Smith, E. L., & Neupert, S. D. (2020). Daily Stressor exposure: Examining interactions of delinquent networks, Daily Mindfulness and Control among emerging adults. Current Psychology, 1–9.

Stravynski, A., & Boyer, R. (2001). Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: A population-wide study. Suicide and Life-threatening Behavior, 31(1), 32–40.

Taylor, S. E., & Stanton, A. L. (2007). Coping resources, coping processes, and mental health. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 3, 377–401.

Thompson, S. C., Sobolew-Shubin, A., Galbraith, M. E., Schwankovsky, L., & Cruzen, D. (1993). Maintaining perceptions of control: Finding perceived control in low-control circumstances. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 293.

Twenge, J. M., Baumeister, R. F., DeWall, C. N., Ciarocco, N. J., & Bartels, J. M. (2007). Social exclusion decreases prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 56.

Winningham, R. G., & Pike, N. L. (2007). A cognitive intervention to enhance institutionalized older adults’ social support networks and decrease loneliness. Aging & Mental Health, 11(6), 716–721.

Yan, L., Gan, Y., Ding, X., Wu, J., & Duan, H. (2021). The relationship between perceived stress and emotional distress during the COVID-19 outbreak: Effects of boredom proneness and coping style. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 77, 102328.

You, S., Hong, S., & Ho, H. Z. (2011). Longitudinal effects of perceived control on academic achievement. The Journal of Educational Research, 104(4), 253–266.

Yue, C., Liu, C., Wang, J., Zhang, M., Wu, H., Li, C., & Yang, X. (2020). Association between social support and anxiety among pregnant women in the third trimester during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in Qingdao, China: The mediating effect of risk perception. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry.

Zhao, X., & Shi, C. (2020). Loneliness of adult and juvenile prisoner influences on psychological affect: Mediation role of control source. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 17(2), 93–100.

Zhou, L., Li, Z., Hu, M., & Xiao, S. (2012). Reliability and validity of ULS-8 loneliness scale in elderly samples in a rural community. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue bao Yi xue ban = Journal of Central South University Medical Sciences, 37(11), 1124–1128.

Zhou, S. J., Wang, L. L., Qi, M., Yang, X. J., Gao, L., Zhang, S. Y.,... & Chen, J. X. (2021). Depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation in Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669833.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the [Shenzhen-Hong Kong Institute of Brain Science-Shenzhen Fundamental Research Institutions] under Grant [2019SHIBS0003]; [Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province] under Grant [2022A151501097]; [National Natural Science Foundation of China] under Grant [31920103009].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Interest statement

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, L., Ding, X., Gan, Y. et al. The impact of loneliness on depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: a two-wave follow-up study. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05898-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05898-6