Abstract

Bereaved by suicide face unique challenges and have differences in their language compared to bereaved by other causes of death, however their language during therapy has not been studied yet. This study investigates the association between patients’ language and reduction in prolonged grief symptoms in an internet-based intervention for people bereaved by suicide. Data stems from a randomized controlled trial including 47 people completing self-reported surveys. Patient language was analyzed using the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count program. Symptom change was determined through absolute change scores. Stepwise forward regression and repeated measures analyses of variances were calculated. During confrontation, a higher reduction of prolonged grief symptoms was predicted by more words describing perceptual (β = − 0.43, p = .002) and cognitive processes (β = − 0.63, p = .002) and less present focus words (β = 0.66, p = .002). During cognitive restructuring, more words describing drives (β = − 0.40, p = .004), less past focus words (β = 0.59, p = .002) and less informal language (β = 0.40, p = .01) predicted a higher reduction of prolonged grief symptoms. Lastly, during behavioral activation, more past focus words (β = − 0.54, p = .002) predicted a higher grief reduction. Findings underline the importance of exposure and cognitive restructuring during therapy and further suggest the relevance of the previously not studied linguistic perceptual processes. Moreover, this study emphasizes the importance of different tenses throughout the intervention, adding knowledge to previous studies assessing time at a single point in therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to digitalization and a more frequent use of the internet, studies on internet-based interventions for the treatment of mental illnesses have been increasing over the past years (Zuelke et al., 2021). Internet-based interventions have proven to be effective in treating various mental disorders, such as depression or panic disorder, and effects are comparable to face-to-face interventions (Carlbring et al., 2018; Richards et al., 2018; Stech et al., 2020). They also have been shown to effectively treat prolonged grief disorder (PGD), which has been recently added as a new diagnosis in the ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2021; Kaiser et al., 2022; Treml et al., 2021; WHO, 2018). Core diagnostic criteria according to the ICD-11 include persistent or pervasive yearning or longing for the deceased, functional impairment and symptoms of emotional pain lasting for at least six months, or in the case of the DSM-5-TR, 12 months.

Internet-based interventions for prolonged grief symptoms are often based on Boelen’s et al. (2006) cognitive-behavioural model and therefore employ three processes during treatment. Treatment includes exposure, in which patients have to face previously avoided aspects of the loss experience to process and integrate the loss into the autobiographical memory (Boelen et al., 2006; Eisma et al., 2015). This is followed by cognitive restructuring, with patients addressing own misinterpretations and dysfunctional thoughts. Lastly, behavioral activation intends patients to resume supportive activities (Boelen et al., 2006; Boelen & Van Den Bout, 2010; Eisma et al., 2015).

While internet-based interventions were found to be effective for prolonged grief symptoms for different bereavement groups, individual differences are often overlooked. Differences in changes between intervention and control groups are often significant, leading to medium to high effect sizes (Wagner et al., 2020), however only 37–47% of patients seem to have clinical significant change after the intervention (Eisma et al., 2015; Kaiser et al., 2022; Treml et al., 2021). Therefore, it is necessary to examine influencing factors on symptom change.

While there are many studies examining the influence of patient or therapist characteristics and therapy-specific variables on symptom change (Boelen et al., 2011; Bryant et al., 2017; Haller et al., 2023), the role of patient language for treatment outcome in internet-based interventions is often overlooked. For the objective assessment of patient language during therapy, a program has been established by Pennebaker and colleagues (2015), the linguistic inquiry word count (LIWC). This method analyses patients’ therapy texts by counting and categorizing every word in patients’ writing tasks into different linguistic categories, e.g., social processes (you, we, friend, mother), insight words (know, think, how) or time words (when, then, now). Studies show that different word categories have been found to impact face-to-face therapy outcomes, e.g. affective words (e.g., positive emotion words [love, nice, sweet] or negative emotion words [hurt, ugly, nasty], Arntz et al., 2012), cognitive processes (cause, know, ough, Jennings et al., 2021) or time words (e.g., past focus words [ago, did, talked] or present focus words [today, is, now], Arntz et al., 2012; Huston et al., 2019; Morrison, 2015). However, there are still some inconsistencies, as for example, both a positive and a negative relationship between past focus words and treatment outcome has been found (Huston et al., 2019; Morrison, 2015). Moreover, perceptual processes have been shown to predict treatment outcome in PTSD (Kindt et al., 2007). However, perceptual processes (LIWC: look, heard, feeling) were operationalized as perceptual memory representations in previous studies and not yet studied with the tool of LIWC. Nevertheless, because many Internet-based therapies involve exposure, patients may also address experiences of their own perceptual processes, which in turn could have an impact on treatment outcome and should therefore be studied. Moreover, as face-to-face therapies differ from internet-based approaches, the generalizability of previous results may be limited. For example, while in some cases of face-to-face therapy, sessions were transcripted, other results stem from the analysis of words written in short essays before treatment and therefore differ from structured writing tasks used in internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (Arntz et al., 2012; Huston et al., 2019).

Studies on the association between patient language and treatment outcome in internet-based interventions are scarce. In internet-based treatments, affective words (e.g., negative emotion words like hurt, ugly, nasty), cognitive processes words (cause, know, ough) or biological processes (eat, blood, pain) were found to be associated with better treatment outcomes (Burkhardt et al., 2021; Owen et al., 2005; Van der Zanden et al., 2014). Moreover, social processes (you, we, friend, mother) were found to predict adherence to therapy (Van der Zanden et al., 2014). Additionally, more words describing behavioral activation and less words describing negative emotions and health were found to be predictive of an increase in patients’ mood (Hernandez-Ramos et al., 2022).

However, there is only one study investigating linguistic predictors of symptom change for prolonged grief symptoms, which found a higher engagement in exposure, as well as cognitive restructuring and a higher time focus at the end of treatment to be associated with a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms (Schmidt et al., 2023). While this study investigated predictors of symptom change for prolonged grief symptoms, it only included people bereaved by cancer. However, there are several other high-risk populations for the development of prolonged grief symptoms, including people bereaved by suicide (Young et al., 2012). While grieving after a loss due to suicide may be similar to grief experiences after other losses (Sveen & Walby, 2008), bereaved are confronted with a variety of problems, that are specific for this bereavement group. As the loss of a person due to suicide is sudden, bereaved experience more feelings of shame, rejection and stigmatization after a loss due to suicide (Andriessen et al., 2017; Sveen & Walby, 2008). The differences between bereaved by suicide and bereaved by other causes of death are also evident in their language use. For example, Lester (2012) found bereaved by suicide to use less words related to death and more words describing sadness or anger compared to bereaved by natural causes. Therefore, patient language in internet-based therapies may also differ between bereaved of different causes of death, potentially influencing the impact on symptom change. However, linguistic predictors of symptom change in people bereaved by suicide have been not studied yet. Moreover, while previous work examined the linguistic predictors individually for each of the three elements of the cognitive behavioral model (exposure, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation), it did not examine how language differs between these three elements of therapy. However, to better understand the language of patients in therapies and potentially improve future interventions, knowledge on the change of language throughout therapy is necessary.

Thus, there is still a research gap in how the language of people bereaved by suicide might change during an internet-based therapy and predict a reduction in prolonged grief symptoms. Nevertheless, it seems important to better understand how text-based interventions may be influenced by patients’ language to provide insights into treatment mechanisms. Thus, therapist feedback in Internet-based therapies could potentially be adapted to tailor future interventions to individual needs. This seems particularly important given the scarcity of grief intervention studies for people bereaved by suicide and their increased vulnerability to poor mental health (Andriessen et al., 2019; Pitman et al., 2014).

Based on these gaps, this study aims to increase knowledge in the specific area of patient language for people bereaved by suicide seeking treatment for prolonged grief symptoms. Specifically, the aims were to investigate (1) patients’ word use as predictors of symptom reduction in prolonged grief symptoms and (2) change of patients’ word use throughout the three elements of treatment (exposure, cognitive restructuring, behavioral activation) in an internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention for people bereaved by suicide suffering from prolonged grief symptoms.

Methods

Procedure

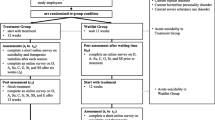

This study is a secondary analysis of a randomized-controlled trial, in which an internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention for people bereaved by suicide was found to be effective (between-group effect size for completers d = 1.03, [details omitted for double-anonymized peer review]). Participants were assigned to either the intervention group or the waitlist-control group using the RITA-Randomization In Treatment Arms (Pahlke et al., 2004). Therapists enrolled participants and assigned them to the intervention or waitlist-control group according to the randomization. Participants from the waitlist-control group also took part in the intervention after a 5-week waiting period. Because both groups completed the intervention, data of both groups was merged.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig (reference number: 319-14-06102014) and has the Clinical Registration Number [details omitted for double-anonymized peer review]. All participants provided written informed consent to participate and publish their data anonymously.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study had following inclusion criteria: (1) loss of a loved one due to suicide, (2) loss occurred at least 14 months ago (to avoid anniversary effects), (3) Internet access, (4) age of 18 years or above, (5) provision of written informed consent, and (6) fulfillment of the criteria for prolonged grief symptoms (assessed by a telephone interview, prolonged grief disorder questionnaire, PG-13 by Prigerson et al., 2009).

Because at the time of study, no instrument for measuring PGD according to the recent criteria were available, the PG-13-questionnaire by Prigerson et al. (2009) was used. Moreover, as many previous studies did not assess PGD according to the recent criteria, the term prolonged grief symptoms is used throughout the current study.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) Experience of psychoticism (scale for psychoticism in Brief Symptom Inventory by Derogatis, 1993), (2) change in psychopharmacological treatment during the last six weeks, (3) substance dependence disorder (questions for alcohol or drug dependence, ICD-10, WHO, 2004), (4) current psychotherapy, and (5) acute suicidal ideation (Yale Evaluation of Suicidality Scale > 3, Latham & Prigerson, 2004). If exclusion criteria were met, participants were contacted through telephone to confirm exclusion and/or provide information for support opportunities.

Participants

After screening 129 participants, 59 were randomized and 57 took part in the assessment before the intervention (2 dropouts after randomization, both reported to not have time for the study anymore). Another eight participants dropped out during or after the intervention (4 dropouts because no more time/too burdensome, 4 dropouts because not responsive at post-test/missing data), leading to n = 49 participants at the assessment post-treatment. Due to data storage error of therapy texts of two participants, the final sample of the current study included N = 47 participants (see study enrolment flow in Online Resource 1).

Sampling and sample size

Initially, a sample size of n = 102 was calculated to achieve sufficient power for the detection of a moderate effect (d = 0.50, α = 0.05, power 1-β = 0.80). With the expectation of a 14% dropout rate, a sample size of n = 116 was determined. While this criterion was not met, the sample size for the efficacy of the treatment (n = 58 with a low dropout rate) was enough for the detection of a large effect (see [details omitted for double-anonymized peer review]). Similarly, when merging both groups and analyzing the therapy texts, the sample size of N = 47 was enough to detect a high explained variance (adjusted R² = 0.51, Cohen et al., 1988).

Intervention

The internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy lasted 5 weeks, with two writing assignments every week, each lasting 45 min. It was based on Boelen’s et al. (2006) cognitive behavioral model and consisted of three modules. The first two modules included four writing assignments each and the last module included two writing assignments. During confrontation participants had to write in detail about their loss experience in present tense, including feelings, sensory perceptions and thoughts to facilitate the processing of the loss. During cognitive restructuring participants had to write letters to a friend (real or imaginary) and imagine this friend had suffered their loss. They had to address difficult thoughts, feelings and dysfunctional interpretations to facilitate a new perspective and restructuring of dysfunctional interpretations. Lastly, during social sharing participants had to write a letter to themselves or a friend involved in the loss, sharing experiences of the past loss, recapitulate what was learned in therapy and share their plans and strategies for their future.

Instructions for the modules were standardized and feedback from therapists was highly structured and given within one day after the writing assignments.

Measures

Prolonged grief symptoms were measured according to the criteria by Prigerson et al. (2009) using the Inventory of Complicated Grief (Prigerson et al., 1995). This instrument contains 19 items which can be answered on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = always). The present study showed good internal consistency (α = 0.83). This scale was used at assessment before and after treatment.

For the analysis of patients’ text, the linguistic inquiry and word count program was used in German language (LIWC, Meier et al., 2019; Pennebaker et al., 2015). Beforehand, patient’s text were checked and corrected for typographical errors. The program analyzes each word and assigns it to a word category. A score representing the percentage of the word category compared to the total number of words is then calculated. Therapy texts consisted of writing tasks provided by patients following the instructions described above (in the Intervention section). The program has been shown to be reliable and valid and provides an objective output for different word categories (Pennebaker et al., 2015).

Because the LIWC contains a high number of word categories (97 word categories), and because previous studies frequently only included a subset of subcategories, we included all higher-order summary variables in the analysis. While most higher-order summary variables were mentioned in the introduction, the summary variables drives (success, better, win) and relativity (area, exit, arrive) were not yet studied and therefore included in this present study. In this way we could insure the consideration of each higher-order word category. This seemed important because most previous studies did not investigate word categories individually for each module, possibly limiting generalizability. Furthermore, as our interest was to examine content-related word categories to possibly improve therapist feedback, word categories only including linguistic features or grammar (e.g., articles, prepositions) were excluded. This resulted in the following summary variables for analysis: affective processes (happy, cried), social processes (mother, daughter, talk), cognitive processes (think, know, because, effect), perceptual processes (see, hear, feel), biological processes (blood, pain, eat), drives (success, better, win), time orientations (past focus [ago, did, talked], present focus [today, is now] and future focus [may, will, soon]), relativity (area, exit, arrive) and informal language (lol, ok, thx). To examine the three modules of the internet-based therapy, therapy texts were combined for each module and the eleven summary word categories were calculated individually for each module, resulting in 33 variables.

Data collection

Recruitment took place between July 2015 and March 2017 via posting information about the study on social media platforms, online support groups and psychology blogs and websites, as well as releasing of a press information and via sending information about the study to health offices, clinics, insurance companies and churches. For data collection, participants received a link send to their e-mail address to fill out self-reported questionnaires before, during and after the intervention and/or waitlist. Therapy was administered at the online platform Minddistrict, where participants could send their therapy-texts and received feedback. Therapy-texts were than copied into the LIWC-program.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS (version 27, SPSS Inc.). As a preliminary analysis, means (SDs) for initial prolonged grief symptoms, symptom reduction and demographic variables were calculated. The equivalence of the intervention and waitlist-control group, as well as completers and dropouts were investigated using two-tailored t-tests and Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests.

To examine predictors of symptom change, absolute change scores were calculated, subtracting initial prolonged grief symptom scores from post-treatment scores. Absolute change scores have been employed in previous literature on factors associated with change in grief symptoms (Bryant et al., 2017) and described as superior to other measurements for change scores, such as relative change scores (Mattes & Roheger, 2020). Because of the high number of predictor variables, a stepwise forward regression with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) as an exploratory analysis was performed using absolute change scores in prolonged grief symptoms as the dependent variable and the different word categories as the independent variables. Assumptions for the regression analyses were checked beforehand. For sensitivity analysis, a stepwise forward regression with adjusted R-squared was performed. Adjusted R-Squared was used as an alternative measure for good model fit, as it relies on a different statistical basis than the AIC (Harrell, 2015).

To investigate the change of the word categories throughout the modules, repeated measures analysis of variances (ANOVA’s) with time (module 1, 2, 3) and word categories that became significant in the regression analysis were calculated and assumptions were checked and met beforehand. The Greenhouse–Geisser adjustment was used to correct for violations of sphericity. Lastly, post-hoc tests for pairwise comparisons of the different modules were examined. To account for multiple tests, all analyses (regression, ANOVA and post-hoc tests) were corrected by the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) correction.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Most participants were women (89.36%), reported to have had a high education (68.09%), had children (59.57%), were in a partnership (59.57%) and were not religious (59.57%). The mean age of the study sample was 45.19 years (SD = 14.78). Most reported methods for suicide of participants’ loved one were hanging (23.40%), followed by poisoning (19.15%), jumping from high places or in front of vehicles (14.89% respectively) and use of firearm (10.64%).

The intervention and waitlist-control group, as well as completers and dropouts did not significantly differ in demographic variables (see Online Resource 2).

Predictors of symptom change

Regression analysis yielded a significant prediction model (F(8, 38) = 7.07). The model contained eight variables and therefore the number of subjects per variable required for the analysis was in line with Austin and Steyerberg (2015).

Seven variables significantly predicted symptom change in grief symptoms. In the first module more words describing perceptual processes (see, hear, feel, β = − 0.43, p = .002), more words describing cognitive processes (think, know, because, β = − 0.63, p = .002) and less present focus words (today, is now, β = 0.66, p = .002) predicted a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms.

During the second module, more words describing drives (success, better, win, β = − 0.40, p = .004), less past focus words (ago, did, talked, β = 0.59, p = .002), and less informal language (lol, ok, thx, β = 0.40, p = .01) predicted a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms.

During the last module, more past focus words predicted a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms (β = − 0.54, p = .002), while present focus words were non-significant (β = − 0.27, p = .08, see Table 1). Significant effects did not change when controlling for participants’ characteristics (see Online Resource 3). A sensitivity analysis yielded a similar prediction model (see Online Resource 4). While the prediction model with the adjusted R-squared for the alternative goodness-of-fit measure included two additional variables (relativity in module 1 [area, bend, exit] and perceptual processes in module 3 [see, hear, feel]), these variables did not significantly predict the reduction of prolonged grief symptoms (relativity module 1: β = − 0.17, p = .17, perceptual processes module 3: β = 0.17, p = .17). The other variables remained significant, except for present focus in module 3, which also remained insignificant (β = − 0.28, p = .06).

Change of word categories throughout modules

Repeated measures ANOVA’s revealed that all six word categories included in the regression model significantly changed throughout modules (see Table 2, see Online Resource 5).

Post-hoc tests showed significantly more perceptual processes in confrontation than in the other two modules (p = .002, p = .002). Moreover, present focus words were significantly higher in confrontation than in social sharing (p = .002), as well as higher in in cognitive restructuring than in social sharing (p = .002).

Post-hoc test further showed significantly more words describing cognitive processes in cognitive restructuring than in the other two modules (p = .007, p = .02). Furthermore, past focus words were significantly higher in social sharing than in cognitive restructuring (p = .002). Additionally, informal language was higher in cognitive restructuring than in the other two modules (p = .05, p = .002), as well as higher in confrontation than in social sharing (p = .002). Lastly, due to the Benjamin-Hochberg correction for post-tests, the differences between the individual modules for words describing drive processes became non-significant.

Discussion

This study set out to investigate linguistic predictors of symptom change, as well as change of word categories throughout therapy in an internet-based intervention for people bereaved by suicide. Results show that words describing perceptual processes (see, hear, feel) decreased significantly from the beginning to the end of therapy and that more words describing perceptual processes during confrontation were predictive of a higher symptom reduction in prolonged grief symptoms. This may be because greater use of words describing perceptual processes implies greater engagement in confrontation with difficult aspects of the loss, as participants describe what they feel, see and hear during their loss experience. Therefore results are in line with previous studies describing exposure as an important component in cognitive-behavioral treatment (Boelen et al., 2007; Bryant et al., 2017; Eisma et al., 2015). For the treatment of prolonged grief symptoms, exposure was found “essential” and has even been found effective as an individual treatment component (Bryant et al., 2014, p. 1337; Eisma et al., 2015). Moreover, it may facilitate subsequent cognitive restructuring, as treatment in which exposure was followed by cognitive restructuring achieved higher effects than treatment with the reverse order (Boelen et al., 2007). Because in some clinical settings there is a concern that exposure may have adverse effects, results confirm that exposure is important in the treatment of prolonged grief symptoms and should be implemented by clinicians (Bryant et al., 2014). Furthermore, previous studies have examined linguistic perceptual processes only in relation to symptom severity of various disorders (e.g., PTSD, anxiety, Paquet et al., 2020; Stamatis et al., 2022), but not to treatment outcome in therapies. Only Schmidt and colleagues (2023) studied perceptual processes in relation to treatment outcome, however they did not emerge as a significant predictor for the reduction of prolonged grief symptoms in bereaved by cancer. Lester (2012, p. 189) found that the language of bereaved by suicide included more words describing sadness and anger, as well as bereavement-related words compared to bereaved by natural causes, therefore he suggested that “the deaths from suicide had a more profound impact” on bereaved than deaths by natural causes. Thus, the inclusion of perceptual processes during exposure could be particularly important for the processing of the loss for bereaved by suicide, as they in some cases may even find the deceased body (Callahan, 2000).

Moreover, words describing cognitive processes (think, know, because, effect) were higher during cognitive restructuring than in confrontation and social sharing, which is in line with the instructions for the writing assignments. Furthermore, more words describing cognitive processes during the first module were predictive of a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms, indicating that cognitive processes may be important during exposure. Similarly, a higher use of words for cognitive process throughout therapy has been found to be associated with improvement in quality of life variables (Owen et al., 2005). Moreover, higher cognitive processing was shown to relate to symptom improvement in PTSD or Borderline personality disorder (Jennings et al., 2021; McMain et al., 2013). Furthermore, greater cognitive restructuring has also been found to correlate with improvements in health (Warner, 2005). Therefore, cognitive processing may be important for the treatment of different disorders.

In addition, while present focus words (today, is, now) significantly decreased throughout therapy, more present focus words during the first module predicted less reduction in prolonged grief symptoms. Previous studies found higher use of present focus words in individuals with PTSD compared to individuals who did not develop PTSD following trauma, suggesting that the present tense may be an indication that individuals perceive the event occurring in the present (Jelinek et al., 2010). Therefore, present focus words could indicate a higher activation of the loss experience. However, because the instruction for the first module was to write about the loss experience in present tense, further dismantling studies are needed to investigate effects depending on different tense instructions. Moreover, previous studies have found an increase in present tense verbs throughout treatment in different study samples (e.g., expressive writing treatment in women with history of sexual abuse, Pulverman et al., 2015 or writing of short essays in patients with personality disorders, Arntz et al., 2012), however, as instructions for writing assignments were different, generalizability is limited.

During the second module, more words describing drives (success, better, win) were associated with a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms. As words describing drives include achievement, power and reward words (see Meier et al., 2019), this may reflect the change of perspective in patients and therefore indicate cognitive restructuring. Results are consistent with previous studies finding high engagement in cognitive restructuring as a protective factor for prolonged grief symptoms, as well as beneficial for symptom reduction (Harper et al., 2014; Schmidt et al., 2023). Furthermore, less informal language (lol, ok, thy) during the second module was associated with a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms. As informal language indicates lower analytic thinking (Jordan et al., 2019), this may impede cognitive restructuring processes. Moreover, informal language may be associated with greater symptoms in different mental disorders, as it has been found to correlate with higher symptoms in anxiety and depression (Stamatis et al., 2022). However, as drives and informal language have only once been investigated in a previous study, where both did not emerge as significant predictors (Schmidt et al., 2023), further studies are necessary.

Results further show that the past focus significantly increased from the second to the third module and that more past focus words during the third module predicted a greater reduction in prolonged grief symptoms, while more past focus words during the second module predicted a lower reduction. While a decrease of past tense words has been found in a previous study by Arntz and colleagues (2012), it was based on the analysis of short essays written by patients about their own life instead of therapy-based writing assignments, limiting generalizability. Moreover, previous studies showed ambivalent results regarding past focus words, as positive and negative relationships with treatment outcomes have been found (Huston et al., 2019; Morrison, 2015). This may be the case because previous studies assessed past focus words throughout treatment and did not distinguish between different modules or time points of therapy. Results imply that while the focus on the past may be detrimental during cognitive restructuring, it may beneficial to include past experiences related to the loss in social sharing at the end of therapy. To integrate results found in this present study into therapies, further studies are necessary. These should also be conducted during particularly challenging times, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only had a negative impact on the general population in various areas, but also on the grieving process (Amuda et al., 2022; Holland et al., 2021; Sankova et al., 2021).

Limitations

It is important to note that this study has several limitations. First, because 89.36% of participants were women and 68.09% reported to have had a high education, generalizability may be limited. Moreover, because the analyses were exploratory with a relatively small sample size, other potential confounders may not have been considered. Future studies should aim for a larger sample size and may investigate causal relationships.

Moreover, causal attributions were not possible due to the design of the study. Future studies may compare an intervention group with a control group using different writing exercises to allow interaction and repeated measure analysis. Additionally, prolonged grief symptoms were assessed via self-report measures instead of clinical interviews. Nevertheless, criteria for prolonged grief symptoms were checked via a telephone interview before inclusion.

Furthermore, as at the time of the study no measurement tool for the current criteria for PGD existed, future studies should consider capturing PGD according to the ICD-11 or DSM-5-TR. Moreover, results may reflect adherence to instructions for the writing assignments to some degree, although not all word categories are covered in the instructions. Lastly, only patient language was considered in this study, as the number of therapists was limited. Future studies may investigate the influence of therapists’ feedback on symptom improvement by analyzing therapist language.

Conclusions

This present publication is the first study to investigate the association between patients’ language and symptom reduction in people bereaved by suicide. This seems particularly important, as bereaved by suicide face unique challenges and have differences in their language use compared to bereaved by other causes. Results show that a higher reduction in prolonged grief symptoms was predicted by (a) more perceptual and cognitive processes and less present tense during exposure (b) more words describing drives, less informal language and less present tense during cognitive restructuring and (c) more past tense during behavioral activation.

Results suggest that a higher engagement in exposure and cognitive restructuring, as well as mentioning of past experiences during behavioral activation may be beneficial in the treatment of prolonged grief symptoms. This may be important for future studies, as therapists may consider the extent to which patients engage in exposure and cognitive restructuring and directly address lack of perceptual or cognitive processes or change in perspective in their feedback and encourage patients to express different perception modalities. This is important, as perceptual processes in patients’ language have not been studied in previous studies before.

Moreover, this study emphasizes the importance of different tenses throughout the intervention, as previous studies often assessed tenses only at one time of the intervention or did not differentiate between different tenses. Future studies could analyze patients’ language throughout therapy and investigate how therapist feedback based on the language outcomes in the LIWC during therapy may influence treatment outcome. It would also be interesting to examine how therapists’ feedback may be associated with treatment outcome, particularly in a structured intervention similarly to the present study. Lastly, further studies could investigate how future interventions could be adapted to tailor individual patient language.

Data Availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PGD:

-

Prolonged grief disorder

- LIWC:

-

Linguistic inquiry and word count program

- PTSD:

-

Posttraumatic stress disorder

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- ICD-11:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- DSM-5-TR:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2021). Diagnostic and statistical manualof mental disorders, Fifth Edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR (TM)). American Psychiatric Association.

Amuda, Y. J., Chikhaoui, E., Hassan, S., & Dhali, M. (2022). Qualitative exploration of Legal, Economic and Health impacts of Covid-19 in Saudi Arabia. Emerging Science Journal, 6, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2022-SPER-01

Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., & Tekavčič-Grad, O. (2017). Postvention in action: The international handbook of Suicide bereavement support. Hogrefe Publishing.

Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Hill, N. T. M., Reifels, L., Robinson, J., Reavley, N., & Pirkis, J. (2019). Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through Suicide: A systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. Bmc Psychiatry, 19(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2020-z

Arntz, A., Hawke, L. D., Bamelis, L., Spinhoven, P., & Molendijk, M. L. (2012). Changes in natural language use as an indicator of psychotherapeutic change in personality disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.007

Austin, P. C., & Steyerberg, E. W. (2015). The number of subjects per variable required in linear regression analyses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68(6), 627–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.014

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false Discovery Rate—A practical and powerful Approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Methodological, 57, 289–300.

Boelen, P. A., & Van Den Bout, J. (2010). Anxious and depressive avoidance and symptoms of prolonged grief, Depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychologica Belgica, 50(1–2), 1–2.

Boelen, P. A., Van Den Hout, M. A., & Van Den Bout, J. (2006). A cognitive-behavioral conceptualization of complicated grief. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00013.x

Boelen, P. A., de Keijser, J., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2007). Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.277

Boelen, P. A., de Keijser, J., van den Hout, M. A., & van den Bout, J. (2011). Factors associated with outcome of cognitive-behavioural therapy for complicated grief: A preliminary study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(4), 284–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.720

Bryant, R. A., Kenny, L., Joscelyne, A., Rawson, N., Maccallum, F., Cahill, C., Hopwood, S., Aderka, I., & Nickerson, A. (2014). Treating prolonged grief disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12), 12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1600

Bryant, R. A., Kenny, L., Joscelyne, A., Rawson, N., Maccallum, F., Cahill, C., & Hopwood, S. (2017). Predictors of treatment response for cognitive behaviour therapy for prolonged grief disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(6), 6. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1556551

Bryant, R. A., Kenny, L., Joscelyne, A., Rawson, N., Maccallum, F., Cahill, C., Hopwood, S., & Nickerson, A. (2017). Treating prolonged grief disorder: A 2-Year Follow-Up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(9), 1363–1368. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.16m10729

Burkhardt, H. A., Alexopoulos, G. S., Pullmann, M. D., Hull, T. D., Areán, P. A., & Cohen, T. (2021). Behavioral activation and Depression Symptomatology: Longitudinal Assessment of linguistic indicators in text-based Therapy Sessions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(7), e28244. https://doi.org/10.2196/28244

Callahan, J. (2000). Predictors and correlates of bereavement in Suicide support group participants. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, 30(2), 104–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2000.tb01070.x

Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., & Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. (2018). Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) administration, scoring, & procedures manual (Fourth ed.). NCS Pearson, Inc.

Eisma, M. C., Boelen, P. A., van den Bout, J., Stroebe, W., Schut, H. A. W., Lancee, J., & Stroebe, M. S. (2015). Internet-based exposure and behavioral activation for complicated grief and rumination: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavior Therapy, 46(6), 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2015.05.007

Harper, M., O’Connor, R. C., & O’Carroll, R. E. (2014). Factors associated with grief and depression following the loss of a child: A multivariate analysis. Psychology Health & Medicine, 19(3), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2013.811274

Haller, K., Becker, P., Niemeyer, H., & Boettcher, J. (2023). Who benefits from guided internet-based interventions? A systematic review of predictors and moderators of treatment outcome. Internet Interventions, 9(33), 100635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2023.100635

Harrell, F. (2015). Regression modeling strategies: With applications to Linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and Survival Analysis (2nd ed.). Springer International Publishing.

Hernandez-Ramos, R., Altszyler, E., Figueroa, C. A., Avila-Garcia, P., & Aguilera, A. (2022). Linguistic analysis of latinx patients’ responses to a text messaging adjunct during cognitive behavioral therapy for depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 150, 104027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.104027

Holland, D. E., Vanderboom, C. E., Dose, A. M., Moore, D., Robinson, K. V., Wild, E., & Griffin, J. M. (2021). Death and grieving for family caregivers of loved ones with life-limiting illnesses in the era of COVID-19: Considerations for case managers. Professional Case Management, 26(2), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCM.0000000000000485

Huston, J., Meier, S., Faith, M., & Reynolds, A. (2019). Exploratory study of automated linguistic analysis for progress monitoring and outcome assessment. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, capr.12219. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12219

Jelinek, L., Stockbauer, C., Randjbar, S., Kellner, M., Ehring, T., & Moritz, S. (2010). Characteristics and organization of the worst moment of trauma memories in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(7), 680–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.014

Jennings, A. N., Soder, H. E., Wardle, M. C., Schmitz, J. M., & Vujanovic, A. A. (2021). Objective analysis of language use in cognitive-behavioral therapy: Associations with symptom change in adults with co-occurring substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 50, 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2020.1819865

Jordan, K. N., Sterling, J., Pennebaker, J. W., & Boyd, R. L. (2019). Examining long-term trends in politics and culture through language of political leaders and cultural institutions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(9), 3476–3481. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1811987116

Kaiser, J., Nagl, M., Hoffmann, R., Linde, K., & Kersting, A. (2022). Therapist-assisted web-based intervention for prolonged grief disorder after Cancer Bereavement: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mental Health, 9(2), e27642. https://doi.org/10.2196/27642

Kindt, M., Buck, N., Arntz, A., & Soeter, M. (2007). Perceptual and conceptual processing as predictors of treatment outcome in PTSD. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 38(4), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.002

Latham, A. E., & Prigerson, H. G. (2004). Suicidality and bereavement: Complicated grief as psychiatric disorder presenting greatest risk for suicidality. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior, 34(4), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.34.4.350.53737

Lester, D. (2012). Bereavement after Suicide: A study of memorials on the internet. Omega-Journal of Death and Dying, 65(3), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.65.3.b

Mattes, A., & Roheger, M. (2020). Nothing wrong about change: The adequate choice of the dependent variable and design in prediction of cognitive training success. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20(1), 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01176-8

McMain, S., Links, P. S., Guimond, T., Wnuk, S., Eynan, R., Bergmans, Y., & Warwar, S. (2013). An exploratory study of the relationship between changes in emotion and cognitive processes and treatment outcome in borderline personality disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 23(6), 658–673. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.838653

Meier, T., Boyd, R. L., Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R., Martin, M., Wolf, M., & Horn, A. B. (2019). LIWC auf Deutsch: The Development, Psychometrics, and Introduction of DE- LIWC2015 [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/uq8zt

Morrison, O. P. (2015). Do the Words People Write Capture Their Process of Change (Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 5655) [University of Windsor]. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5655

Owen, J. E., Klapow, J. C., Roth, D. L., Shuster, J. L., Bellis, J., Meredith, R., & Tucker, D. C. (2005). Randomized pilot of a self-guided internet coping group for women with early-stage Breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3001_7

Pahlke, F., König, I. R., & Ziegler, A. (2004). Randomization in treatment arms (RITA): Ein Randomisierungs-Programm fü̈r klinische Studien. Informatik Biometrie Und Epidemiologie in Medizin Und Biologie, 35(1), 1.

Paquet, C., Cogan, C. M., & Davis, J. L. (2020). An examination of the relationship between language use in post-trauma nightmares and psychological sequelae in a treatment seeking population. International Journal of Dream Research, 13(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/10.11588/ijodr.2020.2.70950

Pennebaker, J. W., Boyd, R. L., Jordan, K., & Blackburn, K. (2015). The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2015. https://doi.org/10.15781/T29G6Z

Pitman, A., Osborn, D., King, M., & Erlangsen, A. (2014). Effects of Suicide bereavement on mental health and Suicide risk. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(1), 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70224-X

Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds, C. F., Bierhals, A. J., Newsom, J. T., Fasiczka, A., Frank, E., Doman, J., & Miller, M. (1995). Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1–2), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2

Prigerson, H. G., Horowitz, M. J., Jacobs, S. C., Parkes, C. M., Aslan, M., Goodkin, K., Raphael, B., Marwit, S. J., Wortman, C., Neimeyer, R. A., Bonanno, G., Block, S. D., Kissane, D., Boelen, P. A., Maercker, A., Litz, B. T., Johnson, J. G., First, M. B., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2009). Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLOS Med, 6(8), 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121

Pulverman, C. S., Lorenz, T. A., & Meston, C. M. (2015). Linguistic changes in expressive writing predict psychological outcomes in women with history of childhood Sexual Abuse and adult sexual dysfunction. Psychological Trauma, 7(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036462

Richards, D., Duffy, D., Burke, J., Anderson, M., Connell, S., & Timulak, L. (2018). Supported internet-delivered cognitive behavior treatment for adults with severe depressive symptoms: A secondary analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 5(4), e10204. https://doi.org/10.2196/10204

Sankova, M. V., Kytko, O. V., Vasil’ev, Y. L., Aleshkina, O. Y., Diachkova, E. Y., Darawsheh, H. M., Kolsanov, A. V., & Dydykin, S. S. (2021). Medical students’ reactive anxiety as a Quality Criterion for Distance Learning during the SARS-COV-2 pandemic. Emerging Science Journal, 5, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.28991/esj-2021-SPER-07

Schmidt, V., Kaiser, J., Treml, J., Linde, K., Nagl, M., & Kersting, A. (2023). Linguistic predictors of symptom change in an internet-based cognitive behavioural intervention for prolonged grief symptoms. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, cpp, 2849. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2849

Stamatis, C. A., Meyerhoff, J., Liu, T., Sherman, G., Wang, H., Liu, T., Curtis, B., Ungar, L. H., & Mohr, D. C. (2022). Prospective associations of text-message‐based sentiment with symptoms of depression, generalized anxiety, and social anxiety. Depression and Anxiety, 39(12), 794–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23286

Stech, E. P., Lim, J., Upton, E. L., & Newby, J. M. (2020). Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(4), 270–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2019.1628808

Sveen, C. A., & Walby, F. A. (2008). Suicide survivors’ mental health and grief reactions: A systematic review of controlled studies. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.13

Treml, J., Nagl, M., Linde, K., Kündiger, C., Peterhänsel, C., & Kersting, A. (2021). Efficacy of an internet-based cognitive-behavioural grief therapy for people bereaved by Suicide: A randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1926650. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1926650

Van der Zanden, R., Curie, K., Van Londen, M., Kramer, J., Steen, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2014). Web-based depression treatment: Associations of clients’ word use with adherence and outcome. Journal of Affective Disorders, 160, 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.005

Wagner, B., Rosenberg, N., Hofmann, L., & Maass, U. (2020). Web-based Bereavement Care: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 525. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00525

Warner, L. J., Lumley, M. A., Casey, R. J., Pierantoni, W., Salazar, R., Zoratti, E. M., & Simon, M. R. (2005). Health effects of written emotional disclosure in adolescents with Asthma: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 557–568. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj048

WHO (2004). ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision, 2nd ed. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980

WHO (2018). ICD-11—International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/en

Young, I. T., Iglewicz, A., Glorioso, D., Lanouette, N., Seay, K., Ilapakurti, M., & Zisook, S. (2012). Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialogues Clinical Neuroscience, 14(2), 177–186. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/iyoung

Zuelke, A. E., Luppa, M., Löbner, M., Pabst, A., Schlapke, C., Stein, J., & Riedel-Heller, S. G. (2021). Effectiveness and feasibility of internet-based interventions for grief after bereavement: Systematic review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 8(12), e29661. https://doi.org/10.2196/29661

Funding

This work was supported by the Roland Ernst Stiftung (grant number 933100-017).

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of Leipzig (reference number: 319-14-06102014).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12144_2023_5525_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 2: Comparison of intervention group with waitlist-group and comparison of completers and dropouts with test statistics

12144_2023_5525_MOESM3_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 3: Regression model of linguistic predictors of symptom change in prolonged grief symptoms controlled for participants’ characteristics

12144_2023_5525_MOESM4_ESM.pdf

Online Resource 4: Sensitivity analysis-regression model with adjusted R-squared for alternative goodness-of-fit measure

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, V., Treml, J., Linde, K. et al. Association between patients’ word use and symptom reduction in an internet-based cognitive behavioral intervention for prolonged grief symptoms: A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Curr Psychol 43, 16489–16498 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05525-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05525-w