Abstract

This study aimed at examining assumptions from Frankl’s (1946/1998) logotherapy and existential analysis. Using an online questionnaire with N = 891 U.K. residents, meaning in life was associated with higher life satisfaction, even when controlling for positive and negative affect. Furthermore, meaning in life intensified the positive effects of family role importance and work role importance on life satisfaction. Lastly, meaning in life neutralised the combined effect of high family strain and high family role importance on lower life satisfaction, but lack of meaning in life aggravated the combined effect of high work strain and high work role importance on lower life satisfaction. This study provides evidence of meaning in life as a source, a contributing factor, and a protective factor of life satisfaction. Helping people to find meaning through fulfilling creative, experiential, and attitudinal values (Frankl, 1950/1996), in personal and/or professional life, is likely to improve life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

The concept of meaning in life (Frankl, 1946/1998) was introduced to psychology, and perhaps to social sciences more widely (Konkoly Thege et al., 2010), more than seventy years ago. Frankl’s (1946/1998) logotherapy and existential analysis have been described as a psychotherapeutic approach and as a philosophical model, respectively, that both put meaning in life at the centre of human existence. Human beings are suggested to search for meaning in life (Frankl, 1947/1994), making people’s will to meaning an important motivational concept. Experiencing meaning in life is not only a uniquely human ability (Frankl, 1946/1998), but is a resource that can positively affect indicators of well-being (e.g., life satisfaction: Abu-Raiya et al., 2021; Joshanloo, 2019; Konkoly Thege & Martos, 2008; Russo-Netzer et al., 2021b; positive affect: Steger et al., 2006; Steger et al., 2009). Furthermore, empirical evidence suggests that meaning in life may have indirect positive effects on various outcome measures (e.g., organisational commitment: Jiang & Johnson, 2018; proactive coping: Miao et al., 2017), which could be mediated through positive reflection on experiences and positive affect respectively. On the other hand, when people’s will to meaning is frustrated—an experience that has been termed existential frustration (Frankl, 1947/1994)—people are more likely to report psychological symptoms (e.g., depression: Konkoly Thege & Martos, 2008) and negative affect (Steger et al., 2006, 2009).

The aim of the current study was to examine a selection of assumptions from Frankl’s (1946/1998) logotherapy and existential analysis, using an instrument that is rooted in this anthropological framework (i.e., Logo-Test: Lukas, 1986; Logo-Test-R: Konkoly Thege et al., 2010). The present study aimed at examining meaning in life as a direct source of life satisfaction, and as a resource that can support life satisfaction (positive psychology perspective) as well as protect against impaired life satisfaction (stress psychology perspective). More specifically, according to Frankl (1946/1998), meaning in life is concerned with people transcending themselves (cf. Maslow, 1967, 1969), and not with seeking pleasant affect and evading negative affect. Accordingly, finding meaning in life may have a positive effect on life satisfaction, irrespective of the affective undertones of such experiences.

Furthermore, meaning in life is not the same as life role importance. Some authors refer to this distinction using the terms ‘meaning’ (i.e., type of experience) and ‘meaningfulness’ (i.e., amount of significance: Rosso et al., 2010, p. 94). Frankl (1950/1996) suggested that prioritising certain life roles, and especially their idolisation (German: ‘Vergötzung’) may have detrimental effects. Accordingly, the bare importance that people attach to life domains may not be sufficient for this resource to display its positive effects on life satsifaction, but such effects may be contingent upon experiencing meaning in life.

Lastly, meaning in life may be a resource that also helps buffering the effects of experiencing life strain. According to Frankl (1947/1994), when people find meaning in life, miserable circumstances may become less important, reducing the negative effects of such experiences on life satisfaction. One example of miserable circumstances may be the situation, when people experience strain in a favoured life domain, making it difficult for them to achieve desired states in this domain (e.g., McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Accordingly, the assumption that meaning in life may buffer the negative effects of high life strain combined with high life role importance on life satisfaction was examined in the current study.

Meaning in life as a source of life satisfaction

According to Frankl (1950/1996), people find meaning in life through fulfilling universal values. Existential analysis suggests that there are three types of such universal values: People can find meaning in life through realising creative values (German: ‘schöpferische Werte’), which refers to any behaviour through which people create or shape something of value. This is not confined to paid labour, but may be displayed in any domain of life. Secondly, people can fulfil experiential values (German: ‘Erlebniswerte’), and such experiences can be socially bound (e.g., love, care), or not socially bound (e.g., appreciating nature or art). Lastly, people can realise attitudinal values (German: ‘Einstellungswerte’), which refers to retaining one’s composure even when exposed to suffering, as long as this suffering is not self-inflicted, but tragic in nature. Importantly, all the above options of finding meaning have in common that people transcend themselves, not focusing mainly on their personal well-being, but devoting themselves to a task or to an experience, or confiding in something or someone even when feeling hopelessness (Frankl, 1950/1996).

Existential analysis suggests that finding meaning in life through fulfilling creative, experiential, and attitudinal values is a rewarding experience in itself (Frankl, 1950/1996), and the main driver of human behaviour (e.g., Konkoly Thege et al., 2010). However, assuming some resemblance of the suggested values with some of the motives suggested by Maslow (1943), especially the higher-order need of self-actualisation, and possibly self-esteem, one might come to the conclusion that finding meaning in life may go along with increased well-being. The notion that need fulfilment is associated with satisfaction has a long tradition in psychology (e.g., Freud, 1920/1978), and also features prominently in theoretical models aiming at explaining motivation at work (e.g., Herzberg, 1968; Porter & Lawler, 1968; for a discussion of meaning of work and work motivation, see Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Furthermore, it might appear plausible that need fulfilment is a positive event that is, therefore, more likely to be associated with pleasant affect than with unpleasant affect (e.g., Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). Accordingly, Kashdan et al. (2008) suggested that psychological well-being, of which meaning in life is a component (Ryff, 1989), is predictive of subjective well-being (Garcia-Alandete, 2015), which comprises satisfaction and pleasant affect (Diener, 1984). Furthermore, Diener et al., (2012, p. 334) suggested that meaning in life may be inherently rewarding, and “might contribute to life satisfaction beyond a person’s pleasant and unpleasant feelings.” Empirical evidence supports the assumption that psychological well-being (Gallagher et al., 2009), and finding meaning in life in particular (Konkoly Thege & Martos, 2008), may be associated with subjective well-being (e.g., Joshanloo, 2019; Ryan & Huta, 2009).

Existential analysis acknowledged the potential positive effect of meaning in life on subjective well-being, but considered this as a mere byproduct of finding meaning in life (Frankl, 1950/1996). Following on from the discussion above, the first hypothesis that was examined in the current study was:

Meaning in life contributes to higher life satisfaction, beyond the effects of positive and negative affect (H1).

Meaning in life as a resource supporting life satisfaction

Frankl (1946/1998) suggested that finding meaning can be considered a psychological resource, even irrespective of any affective undertones that this experience may have. Furthermore, and importantly, fulfilling creative, experiential, and attitudinal values are universal ways to finding meaning in life. In other words, these values, and their meaning, are always already there (Frankl, 1950/1996), but people need to fulfil them in order to find meaning in their lives. Accordingly, the importance that individuals attach to these values, and possibly to corresponding life roles (e.g., work roles and family roles to fulfil creative and experiential values), is not essential for the experience of meaning in life. On the contrary, prioritising some of these values, and especially their idolisation may have severly detrimental effects (Frankl, 1950/1996).

Contemporary psychology often suggests that the psychological importance that people attach to life roles (i.e., life role importance: e.g., Eddleston et al., 2006) is a source of well-being. Bagger et al. (2008) consider life role importance as related to self-definitions and sense of identity. There is empirical evidence suggesting that life role importance (e.g., Wayne et al., 2006) as well as the centrality of certain identity facets (e.g., Mossakowski, 2003) are associated with increased well-being (e.g., life satisfaction: Martire et al., 2000). Such effects may occur because life role importance might give people behavioural guidance (Thoits, 1991), leading to resources being allocated to corresponding life domains (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006), which in turn might result in achieving desired outcomes in those domains (Ford et al., 2007). In one of the rare studies examining the relationships between meaning in life, life role importance, and well-being, role importance was associated with meaning, which, in turn, positively influenced inidicators of well-being in a sample of volunteers (Thoits, 2012).

What might be equally plausible, however, is to consider the positive effects of life role importance as potentially contingent upon experiencing meaning in life. Wayne et al. (2007) argued that positive spillover between life domains (e.g., work domain and family domain enrich each other, rather than being in conflict with each other) can be experienced through fulfilling multiple role responsibilities. The latter notion points to the idea of people transcending themselves (Frankl, 1950/1996; “factors beyond immediate pleasure”: Diener et al., 2012, p. 334), rather than to finding enrichment due to the bare importance attached to the corresponding life roles. Following on from the above discussion, it was hypothesised that meaning in life moderates the association between life role importance and life satisfaction. More specifically the assumptions examined in the current research were:

Meaning in life moderates the association between work role importance and life satisfaction: When meaning in life is high, the association between higher work role importance and higher life satisfaction is stronger than when meaning in life is low (H2 a).

Meaning in life moderates the association between family role importance and life satisfaction: When meaning in life is high, the association between higher family role importance and higher life satisfaction is stronger than when meaning in life is low (H2 b).

Meaning in life as a resource protecting against impaired life satisfaction

For illustrating purposes, Frankl (1946/1998) referred to Nietzsche’s (1889/1997, p. 6) aphorism “If you have your why for life, you can get by with almost any how.—Humanity does not strive for happiness; only the English do.” Existential analysis suggests that when people find meaning in their lives (‘why’), miserable circumstances of these lives (‘how’) become less important. And with explicit reference to attitudinal values, Frankl (1950/1996) suggested that the ‘how’ of suffering points to the ‘why’ of suffering, i.e., the way people suffer is their answer to the question after the why of suffering. Accordingly, meaning in life is described as a resource that can not only contribute to well-being, but also protect against impaired well-being (Frankl, 1947/1994).

The assumption that psychological resources can mitigate negative effects on well-being is common in psychology. In stress psychology, for example, resources, such as self-efficacy, social support, and coping efficacy, are seen as potential buffers of the association between stressor and strain (e.g., Carver et al., 1989; Johnson & Hall, 1988). With view to meaning in life as a potential protective resource, it has been suggested that meaning-making may allow people to react flexibly to and “accommodate stress or trauma” (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009, p. 247). Empirical evidence suggests that meaning in life may indeed be a buffer variable mitigating the negative effect of unpleasant experiences on indicators of well-being (e.g., life satisfaction: Diener et al., 2012; Joshanloo, 2018) as well as on indicators of impaired well-being (e.g., negative affect: Burrow et al., 2014; depression: Guzman, 2017).

The current study focused on the potentially threatening situation of experiencing strain in a domain with high life role importance. As discussed earlier, life role importance may be a resource supporting well-being, but when strain is experienced in the corresponding domain, then life role importance may lose its positive effects (Thoits, 1992), or it might, perhaps, even aggravate negative effects of life strain on well-being. McKnight and Kashdan (2009, p. 244), for example, suggested that people who attach great importance to a certain domain “may become disheartened if the obstacles become too great to overcome”. In one the rare studies about life strain, meaning in life and impaired well-being, Guzman (2017) found particularly high levels of depression in men reporting high work strain and low meaning in life. Guzman’s (2017) study did not allow to examine this, but suggested that lack of meaning in life might aggravate the negative effect of high work strain combined with high work role importance on well-being.

Following on from the discussion above, in the present study, the assumption was that meaning in life could be a protective resource, that buffers negative effects on well-being (Frankl, 1947/1994). More specifically, it was hypothesised that meaning in life moderates the combined effect of life strain and life role importance on life satisfaction. Accordingly, the assumptions examined in the current research were:

Meaning in life moderates the combined effect of work strain and work role importance on life satisfaction: When meaning in life is high, the combined effect of high work strain and high work role importance on lower life satisfaction is weaker than when meaning is life is low (H3 a).

Meaning in life moderates the combined effect of family strain and family role importance on life satisfaction: When meaning in life is high, the combined effect of high family strain and high family role importance on lower life satisfaction is weaker than when meaning is life is low (H3 a).

Study overview and conceptual models

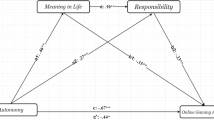

In summary, this study aimed at investigating meaning in life’s direct and moderating effects on life satisfaction. More precisly, the potential effect of meaning in life on life satisfaction was examined (H1) first. Importantly, the assumption was that meaning in life would be associated with life satisfaction, beyond positive and negative affect’s influence on life satisfaction. In the next step, meaning in life was examined as a variable that might support life satisfaction, by strengthening the effects of work role importance (H2 a) as well as family role importance (H2 b) on life satisfaction (positive psychology perspective). Lastly, meaning in life was examined as a variable that might protect against impaired life satisfaction, by buffering the effects of combined work strain and work role importance (H3 a) as well as combined family strain and family role importance (H3 b) on life satisfaction (stress psychology perspective) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Method

Sample and procedure

Eight-hundred-and-ninety-one U.K. resident respondents participated in the study overall. Due to missing data, however, the sample size for analyses varied (N = 838—891), depending on the variables involved. In an attempt to maximise the potential of the current research, and in order to treat study participants with respect (e.g., Oates et al., 2021), the decision was taken not to exclude respondents with partially missing data, but to make the most of the data available. Forty-nine percent of respondents indicated that they were female, 91% described themselves as white, and 98% stated that they were U.K. citizens. Respondents’ average age was 43.3 years (SD = 11.5). In terms of highest educational attainment, 35% of respondents indicated that they had an Undergraduate Degree or Postgraduate Diploma, 29% reported that they were Secondary School leavers, and 18% completed Technical College. Ninety-three percent of respondents indicated that they were currently employed, and respondents had been working with their current employer at an average of 9.3 years (SD = 8.6). The majority of respondents reported to be married (49%), or to be single (28%), and, on average, respondents had one child (SD = 1.3).

Invitations to participate in the study were distributed widely via e-mail. Additionally, the survey was circulated by posting the invitation on internet platforms, that appeared to be relevant to the study’s focus (i.e., well-being in life). Invitations contained an explanation of the aim of the study, along with the assurance that participation would be voluntary, that respondents could withdraw from participating at any time, that their responses would be treated confidentially, and that data would be analysed at aggregate level. Potential respondents willing to participate accessed an online questionnaire through a link at the end of the invitation.

Instruments

Respondents provided demographic information, and answered scales assessing meaning in life, work role importance and family role importance, work strain and family strain, life satisfaction as well as positive and negative affect.

Meaning in life

This variable was assessed using eight items developed by Lukas (1986), which were adapted by Konkoly Thege et al. (2010). Instead of asking directly for levels of meaning in life (e.g., Steger et al., 2006), the instrument captures the extent to which respondents fulfil values, and considers this as an indicator of finding meaning in life. Sample items read ‘There is a special activity that particularly interests me, about which I always want to learn more, and on which I work whenever I have the time’ (creative values), ‘I find pleasure in experiences of certain kinds, e.g., arts, nature, and I do not want to miss out on them’ (experiential values), and ‘When suffering, worry or sickness arises in my life, I make great efforts to improve the situation’ (attitudinal values). Respondents used answer categories ranging from 1 = not characteristic of me at all to 5 = very characteristic of me. Konkoly Thege et al. (2010) reported a scale reliability of α = 0.75 for a 14-item version of the scale. In the current study, the scale had a reliability of α = 0.78.

Life role importance

According to Delle Fave et al. (2011), people see their work role and their family role as the most important (‘meaningful’) domains of their lives, with family being more significant than work. Work role importance and family role importance were assessed using items developed by Lodahl and Kejner (1965) and Lobel and St. Clair (1992), which were adapted by Eddleston et al. (2006). Each scale comprises four items and asks respondents to indicate the importance that they attach to their work role and family role respectively (e.g., ‘I am very much involved personally in my work/family’), with answer categories ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Eddleston et al. (2006) reported scale reliabilities of 0.84 and 0.92 respectively. In the current study, the scale reliabilities were 0.87 and 0.95.

Life strain

Work strain was assessed using a scale developed by Motowidlo et al. (1986), which was used, among others, by Bolino and Turnley (2005). The items were rephrased to capture family strain. A sample item reads: ‘I feel a great deal of stress because of my work/family’, and answer categories range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Bolino and Turnley (2005) reported a scale reliability of 0.87 for work strain. In the current study, the scale reliabilities for work strain and family strain were 0.77 and 0.71 respectively.

Life satisfaction

This variable was assessed using Diener et al.’s (1985) satisfaction with life scale. The scale comprises five items (e.g., ‘I am satisfied with my life’), with answer categories ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Diener et al. (1985) reported a scale reliability of 0.87. In the current study, the reliability of this scale was 0.91.

Positive and negative affect

Using an instrument developed by Watson et al. (1988), respondents indicated the extent to which they had experienced ten positive and ten negative feelings ‘during the past few weeks’ (e.g., ‘proud’, ‘enthusiastic’ and ‘ashamed’, ‘guilty’, respectively). Answer categories ranged from 1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely. Watson et al. (1988) reported scale reliabilities ranging from 0.86 to 0.90 for positive affect and ranging from 0.84 and 0.87 for negative affect. In the current study the reliabilities were 0.89 and 0.92.

Table 1 shows the intercorrelations between study variables, along with descriptive statistics, and scale reliabilities.

Data analysis

Hypotheses were examined with regression analyses, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS-27). The direct association between meaning and life and life satisfaction (H1) was investigated with a regression that additionally contained positive and negative effect as control variables. The latter was done, in order to ensure that a potential effect of meaning in life on life satisfaction was beyond any influence that positive affect and negative affect may have (e.g., Frankl, 1950/1996). Furthermore, this allowed to focus exclusively on life satisfaction as the attitudinal component of subjective well-being (Diener et al., 2012). In the remaining analyses, positive affect and negative effect were included as well. This may, additionally, have addressed potential issues with common method variance, because moods can affect ratings on self-report questionnaires (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Potential moderator effects of meaning in life on the association between work role importance (H2 a) as well as family role importance (H2 b) and life satisfaction were examined using moderated regression analysis (i.e., analyses contained the interaction terms ‘work role importance’ x ‘meaning life’ and ‘family role importance’ x ‘meaning in life’ respectively). The interaction term must yield statistical significance to qualify a moderator effect (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Following a recommendation by Aiken and West (1991), both variables were centred before computing the interaction term. As moderator effects are generally difficult to detect in applied research (Villa et al., 2003), each moderator effect was investigated in a separate regression analysis.

Examining the potential moderator effect of meaning in life on the combined effect of work strain and work role importance (H2 a) as well as family strain and family role importance (H2 b) on life satisfaction, required investigating the three-way interaction terms ‘work strain’ x ‘work role importance’ x ‘meaning in life’ and ‘family strain’ x ‘family role importance’ x ‘meaning in life’ respectively. These regression analyses also contained three two-way interaction terms (i.e., ‘work strain’ x ‘work role importance’, ‘work strain’ x ‘meaning in life’, ‘work role importance’ x ‘meaning in life’, and ‘family strain’ x ‘family role importance’, ‘family strain’ x ‘meaning in life’, ‘family role importance’ x ‘meaning in life’ respectively). This allowed to determine whether the three-way interaction term had a unique additional contribution (Dawson, 2014; Dawson et al., 2006), beyond what might be attributable to two-way interaction terms.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The correlations between study variables presented in Table 1 did not cause concern with regards to common method variance. Nevertheless, using exploratory factor analysis, Harman’s one-factor test was conducted, and did not identify a general or single factor (Podsakoff et al., 2003), but the extracted factor explained 21% of variance. Additionally, confirmatory factor analyses using AMOS-27 showed that an eight-factor model fitted better with the data (χ2 = 7,414.78, df = 1,080, Cmin/df = 6.87, comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.77, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.08) than a one-factor model (χ2 = 21,316.17, df = 1,080, Cmin/df = 19.74, CFI = 0.27, RMSEA = 0.14 [χ2difference = 13,901.39, dfdifference = 7, p < 0.001]). Accordingly, the constructs in the current study may be partly overlapping, but not redundant.

In order to detect additional potentially relevant control variables (i.e., apart from positive affect and negative affect), relationships between respondents’ demographic variables and life satisfaction were explored. These analyses showed that there were no gender differences in life satisfaction (t(850) = 0.21, p = 0.833), that age was unrelated to life satisfaction (r = -0.05, p = 0.181), that level of educational attainment did not affect life satisfaction (F(5,852) = 1.83, p = 0.104), and that there was no association between tenure with current employer and life satisfaction (r = 0.06, p = 0.079). Furthermore, however, number of children was associated with life satisfaction (r = 0.15, p < 0.001), and relationship type was related with life satisfaction (F(4,851) = 20.45, p < 0.001). Follow-up analyses showed that married respondents reported higher life satisfaction than respondents who were not married.

Accordingly, number of children and a dummy-coded variable describing marital status (0 = not married; 1 = married) were entered as additional control variables in analyses. This increased the maximum number of predictor variables from nine (i.e., positive affect and negative affect, meaning in life, work role importance and work strain, or family role importance and family strain respectively, three two-way interaction terms and one three-way interaction term) to eleven. A power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007, 2009) showed that the study’s minimum sample size of N = 838 was still sufficient to detect relatively small effects, with a significance level of α = 0.05, and a power of 1 – β = 0.95.

Meaning in life as a source of life satisfaction (H1)

As can be seen from the correlations presented in Table 1, there was evidence suggesting that, as expected, meaning in life was associated with higher life satisfaction (r = 0.35). When controlling for positive and negative affect, this association remained significant (β = 0.12; see Table 2: step 2). Although not the focus of the first hypothesis, further correlational evidence suggested that meaning in life was also associated with higher positive affect (r = 0.50), higher work role importance as well as higher family role importance (r = 0.41 and r = 0.39 respectively), and lower family strain (r = -0.17).

Meaning in life as a resource supporting life satisfaction (H2)

As expected, the interaction terms work role importance x meaning in life (H2 a) as well as family role importance x meaning in life (H2 b) were significant predictors of life satisfaction (β = 0.06 and β = 0.07 respectively; see Tables 2 and 3: step 4). As is illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4, there were stronger associations between work role importance as well as family role importance and higher life satsfaction for respondents reporting high meaning in life than for respondents reporting low meaning in life. These findings support hypotheses 2 a and 2 b.

Meaning in life as a resource protecting against impaired life satisfaction (H3)

The interaction term work strain x work role importance x meaning in life (H3 a) was a significant predictor of life satisfaction (β = 0.07; see Table 4: step 5). As is illustrated in Fig. 5, there were more pronounced negative associations between work strain and life satisfaction for respondents reporting high work role importance (see regression lines (1) and (3)). For respondents with high work role importance and low meaning in life (see regression line (1)), however, this negative association was stronger. Accordingly, respondents with high work strain, high work role importance, and low meaning in life reported the lowest level of life satisfaction. This finding shows that meaning in life affects the combined effect of work strain and work role importance on life satisfaction. Admittedly, however, as the nature of this interaction effect was not as predicted, this finding lends only partial support to hypothesis 3 a.

The interaction terms work strain x work role importance as well as work role importance x meaning in life were significant predictors of life satisfaction as well (β = -0.08 and β = 0.06 respectively; see Table 4: step 4). However, these interactions were qualified by the three-way interaction.

The interaction term family strain x family role importance x meaning in life (H3 b) was a significant predictor of life satisfaction (β = 0.07; see Table 5: step 5). As is illustrated in Fig. 6, for the majority of respondents, there was a negative association between family strain and life satisfaction (see regression lines (1), (2), and (4)). For respondents with high family role importance and high meaning in life (see regression line (3)), however, there was no association between family strain and life satisfaction. Accordingly, repondents with high family role importance and high meaning in life reported the highest level level of life satisfaction, irrespective of family strain. This finding supports hypothesis 3 b.

The interaction terms family strain x meaning in life as well as family role importance x meaning in life were significant predictors of life satisfaction as well (β = 0.07 and β = 0.08 respectively; see Table 5: step 4). However, these interactions were qualified by the three-way interaction.

Discussion

This study aimed at examining assumptions from Frankl’s (1946/1998) logotherapy and existential analysis, using an instrument assessing meaning in life that is rooted in this anthropological framework (Konkoly Thege et al., 2010; Lukas, 1986). Meaning in life was assumed to be a direct source of well-being, to be a supporting resource contributing to well-being (positive psychology perspective), and to be a protective resource against impaired well-being (stress psychology perspective). Data analyses provided support for most hypotheses.

Analyses showed that meaning in life was a direct predictor of life satisfaction, and this association remained significant, even when controlling for positive and negative affect (H1). This finding is in line with Frankl’s (1950/1996) initial suggestion and evidence reported in the research literature (e.g., Abu-Raiya et al., 2021; Joshanloo, 2019; Russo-Netzer et al., 2021b). Importantly, meaning in life was associated with life satisfaction beyond positive and negative affect, even when using a sample with a considerable proportion of English people (cf. Nietzsche, 1889/1997). Furthermore, the finding indicates that meaning is not mainly concerned with the immediate self-interest of experiencing pleasant feelings (Frankl, 1950/1996; cf. Maslow, 1961), and that life satisfaction, as an attitudinal judgement, is not the same as positive affect (Diener et al., 2012).

Meaning in life intensified the positive effects of work role importance as well as family role importance on life satisfaction (H2 a and H2 b). This finding is aligned with what Frankl (1950/1996) suggested, and with later notions in the research literature (e.g., Wayne et al., 2007). Notably, however, this effect occurred for both work role importance and family role importance, indicating that meaning in life is a resource that can positively affect life satisfaction, irrespective of the particular life domain under consideration. In other words, people may find satisfaction through attaching importance to certain life domains, but finding meaning in life through fulfilling universal values (Frankl, 1950/1996) ensures that life role importance can display its positive effects. Accordingly, fulfilling creative, experiential and attitudinal values, irrespective of any affective undertones of this experience (Frankl, 1946/1998), may be considered a resource supporting life satisfaction across life domains.

Furthermore, study findings suggested that meaning in life may have a buffering effect on the negative influence of family strain combined with family role importance on life satisfaction (H3 b). It had been suggested that life role importance may not only lose its positive effect on well-being, when strain is experienced in the corresponding life domain (Thoits, 1992), but may even have a detrimental effect on well-being (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). Frankl (1946/1998) suggested that when people find meaning in their lives, difficult circumstances become less important, pointing to meaning in life as a resource that may protect against impaired well-being, by allowing flexibility and accommodation (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009). The findings from the current study support this assumption, and extend earlier empirical evidence (e.g., Burrow et al., 2014; Diener et al., 2012), indicating that meaning may not only buffer negative effects of, for example, changes in life satisfaction and unpleasant affect, but also the negative consequences of domain-specific life strain.

With regards to the expectation that meaning in life may equally moderate the negative effect of work strain combined with work role importance (H3 a), the findings of the current study provided only partial support. Meaning in life did not buffer, but lack of meaning in life aggravated the negative effect of work strain combined with work role importance on life satisfaction. Whereas the nature of this interaction effect is not as expected, it is still aligned with the notion in the literature that lack of meaning may be a risk factor (Frankl, 1947/1994), which may contribute to impaired well-being (Guzman, 2017).

The finding that meaning in life buffered negative effects in the family domain, but lack of meaning in life aggravated negative effects in the work domain, may point to important differences between these two life domains. In general, people attach less importance to the work domain than to the family domain (Delle Fave et al., 2011). Furthermore, work domain and family domain may both be considered as obligatory (Thoits, 1992), but the work domain, perhaps, more so than the family domain, because performing work roles may allow less flexibility and autonomy with resource allocation than fulfilling family roles. Accordingly, it may be more difficult for people to use resources to create desired states (Ford et al., 2007) in the work domain than in the family domain.

Limitations and conclusions

Whereas a cross-sectional study design might be deemed appropriate for addressing the aims of the current study, longitudinal data would have allowed interesting data-analytical options. Empirical evidence suggests that meaning in life is not systematically associated with age (e.g., Konkoly Thege et al., 2010), but meaning may still vary over time, possibly resulting in stronger or weaker effects on well-being. Similarly, it would be interesting to account for the extent to which respondents had been exposed to life strain. Perhaps, meaning in life plays a more or less important role, depending on how long people have tried to cope with life strain. The current study only accounted for work role and family role, but there are more life roles (e.g., leisure roles, voluntary unpaid work roles), which may, arguably, also vary with regards to perceived obligation, and could be taken into account in a future study. Furthermore, it may be promising to differentiate between specific roles within a broader life domain (e.g., partner role, parent role), which would allow a more fine-grained analysis. Similarly, it might be interesting to use domain-specific measures of meaning in life (e.g., meaning in work life, meaning in family life), or even to account separately for different types of values (i.e., creative, experiential, and attitudinal values). According to Frankl (1950/1996), these values are universal, and together they form the source of meaning in life. Accordingly, a measure of overall meaning in life was used in the current study. However, differentiating between specific roles within life domains and/or types of values may have resulted in a greater match between predictor, moderator, and outcome variables (Cohen & Wills, 1985; De Jonge & Dormann, 2006), possibly revealing stronger moderator effects.

This study provided evidence of the importance of meaning in life as a resource contributing to well-being and protecting against impaired well-being. Admittedly, the strengths of individual effects were not overwhelming. Taken together, however, meaning in life directly affected life satisfaction, intensified the positive effect of work role importance as well as family role importance, buffered the negative effect of combined family strain and family role importance, and aggravated the negative effect of combined work strain and work role importance. Given that such effects are likely to accumulate over time and situations, this indicates that meaning in life may be a relevant predictor of life satisfaction.

Importantly, Frankl’s (1946/1998) conceptualisation of meaning in life puts much of an emphasis on the notion of people transcending themselves (cf. Maslow, 1967, 1969), but does not present and discuss this mainly with view to religion. Nevertheless, the findings of the current study may contribute to a growing body of knowledge about the importance of spirituality and related concepts, including, but not limited to, gratitude and optimism (e.g., Russo-Netzer et al., 2021a), religiousness (Abu-Raiya et al., 2021), compassion (Aslan et al., 2022), and psychological richness (i.e., variety of experience as a source of well-being: Oishi & Westgate, 2021).

From a more practical perspective, important study implications can be highlighted as well. According to McKnight and Kashdan (2009), understanding how people live can be helpful to give guidance. This can be relevant at individual level (e.g., counselling), but also in organisational settings. Frankl (1950/1996) suggested that people can find meaning through fulfilling creative, experiential, and attitudinal values, and the current study provides evidence that meaning not only directly affects life satisfaction, but additionally in combination with life role importance and life strain. Therefore, in order to positively influence people’s life satisfaction, they could be encouraged to fulfil values in their daily lives. Importantly, meaning in life displays positive effects across life domains. People can benefit from this positive spillover (e.g., Greenhaus & Powell, 2006), in that meaning found through fulfilling any of the three types of universal values, in combination with the importance attached to either of the life domains considered in the current study, may positively affect life satisfaction. Furthermore, people do not necessarily need to suffer from miserable circumstances and adverse events in a specific domain, as this experience might be compensated through finding meaning in another domain. The current study suggests that this may apply to the negative effects of family strain in particular.

Organisations that are interested in their members’ well-being could create opportunities to fulfil values, thereby increasing the likelihood that their members find meaning in life, which in turn may contribute to higher life satisfaction. Furthermore, Cartwright and Holmes (2006) suggested that finding meaning in work may be associated with higher employee engagement and lower cynicism, both of which can be considered as indicators of organisational well-being (e.g., Palmer et al., 2004).

Whilst the adverse health outcomes of work stress are well documented (e.g., psychophysiological strain: Nwaogu & Chan, 2021), the current study focused on the negative effects of work strain on life satisfaction. Work strain is difficult to avoid completely, and employers would usually appreciate high work role importance in their members. Importantly, however, organisations need to ensure that their members do not experience lack of meaning. Based on the findings of the current study, aggravated negative effects of work strain on life satisfaction can be expected, when people experience lack of meaning in life, especially when their work role importance is high.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is available from the author on reasonable request.

References

Abu-Raiya, H., Sasson, T., & Russo-Netzer, P. (2021). Presence of meaning, search for meaning, religiousness, satisfaction with life and depressive symptoms among a diverse Israeli sample. International Journal of Psychology, 56, 276–285.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Aslan, H., Erci, B., & Pekince, H. (2022). Relationship between compassion fatigue in nurses, and work-related stress and the meaning of life. Journal of Religion and Health, 61, 1848–1860.

Bagger, J., Li, A., & Gutek, B. A. (2008). How much do you value your family and does it matter? The joint effects of family identity salience, family-interference-with-work, and gender. Human Relations, 61, 187–211.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2005). The personal costs of citizenship behavior: The relationship between individual initiative and role overload, job stress, and work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 740–748.

Burrow, A. L., Sumner, R., & Ong, A. D. (2014). Perceived change in life satisfaction and daily negative affect: The moderating role of purpose in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 579–592.

Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 199–208.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the moderating hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 1–19.

Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 917–926.

De Jonge, J., & Dormann, C. (2006). Stressors, resources, and strain at work: A longitudinal test of the triple match principle. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1359–1374.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Freire, T., Vella-Brodrick, D., & Wissing, M. P. (2011). The eudaimonic and hedonic components of happiness: Qualitative and quantitative findings. Social Indicators Research, 100, 185–207.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Fujita, F., Tay, L., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2012). Purpose, mood, and pleasure in predicting satisfaction judgments. Social Indicators Research, 105, 333–341.

Eddleston, K. A., Veiga, J. F., & Powell, G. N. (2006). Explaining sex differences in managerial career satisfier preferences: The role of gender self-schema. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 437–445.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 57–80.

Frankl, V. E. (1994) (6th ed.). Trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen [Man’s search for meaning]. München, Germany: Kösel-Verlag. (Original work published 1947)

Frankl, V. E. (1996) (2nd ed.). Homo patiens. Der leidende Mensch [Suffering humanity] (pp. 161–242). Bern, Switzerland: Huber. (Original work published in 1950)

Frankl, V. E. (1998) (7th ed.). Ärztliche Seelsorge [The doctor and the soul]. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Fischer Verlag. (Original work published 1946)

Freud, S. (1978). Jenseits des Lustprinzips [Beyond the pleasure principle]. Das Ich und das Es (pp. 121–170). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Fischer Verlag. (Original work published in 1920)

Gallagher, M. W., Lopez, S. J., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). The hierarchical structure of well-being. Journal of Personality, 77, 1025–1050.

Garcia-Alandete, J. (2015). Does meaning in life predict psychological well-being? An analysis using the Spanish versions of the Purpose-In-Life Test and the Ryff’s scales. The European Journal of Counselling Psychology, 3, 89–98.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

Guzman, A. (2017). The role of perceived stress in the relationship between purpose in life and mental health. The University of New Mexico. Available at: http://digitalrepository.unm.edu/psy_etds/206. Accessed 21 Nov 2022.

Herzberg, F. (1968). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review, 46, 53–62.

Jiang, L., & Johnson, M. J. (2018). Meaningful work and affective commitment: A moderated mediation model of positive work reflection and work centrality. Journal of Business Psychology, 33, 545–558.

Johnson, J. V., & Hall, E. M. (1988). Job strain, work place social support, and cardiovascular disease: A cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. American Journal of Public Health, 78, 1336–1342.

Joshanloo, M. (2018). Income satisfaction is less predictive of life satisfaction in individuals who believe their lives have meaning or purpose: A 94-nation study. Personality and Individual Differences, 129, 92–94.

Joshanloo, M. (2019). Investigating the relationships between subjective well-being and psychological well-being over two decades. Emotion, 19, 183–187.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 219–233.

Konkoly Thege, B., & Martos, T. (2008). Reliability and validity of the shortened Hungarian version of the Existence Scale. Existenzanalyse, 25, 70–74.

Konkoly Thege, B., Martos, T., Bachner, Y. G., & Kushnir, T. (2010). Development and psychometric evaluation of a revised measure of meaning in life: The Logo-Test-R. Studia Psychologica, 52, 133–145.

Lobel, S. A., & St. Clair, L. (1992). Effects of family responsibilities, gender, and career identity salience on performance outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 1057–1069.

Lodahl, T. M., & Kejner, M. (1965). The definition and measurement of job involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 49, 24–33.

Lukas, E. S. (1986). Logo-Test: Test zur Messung von innerer Sinnerfüllung und existenzieller Frustration [A test assessing meaning in life and existential frustration]. Deuticke.

Martire, L. M., Stephens, M. A. P., & Townsend, A. L. (2000). Centrality of women’s multiple roles: Beneficial and detrimental consequences for psychological well-being. Psychology and Aging, 15, 148–156.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370–396.

Maslow, A. H. (1961). Peak experiences as acute identity experiences. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 2, 254–262.

Maslow, A. H. (1967). A theory of metamotivation: The biological rooting of the value-life. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 7, 93–127.

Maslow, A. H. (1969). Various meanings of transcendence. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1, 56–66.

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology, 13, 242–251.

Miao, M., Zheng, L., & Gan, Y. (2017). Meaning in life promotes proactive coping via positive affect: A daily diary study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 1683–1696.

Mossakowski, K. N. (2003). Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health?. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 318–331.

Motowidlo, S. J., Packard, J. S., & Manning, M. R. (1986). Occupational stress: Its causes and consequences for job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71, 618–629.

Nietzsche, F. (1997). Twilight of the idols [Translated by Richard Polt]. Indianapolis, IN, USA: Hackett. (Original work published 1889)

Nwaogu, J. M., & Chan, A. P. C. (2021). Work-related stress, psychophysiological strain, and recovery among on-site construction personnel. Automation in Construction, 125, 103629.

Oates, J., Carpenter, D., Fisher, M., Goodson, S., Hannah, B., Kwiatowski, R., Prutton, K., Reeves, D., & Wainwright, T. (2021). BPS Code of Human Research Ethics. British Psychological Society.

Oishi, S., & Westgate, E. C. (2021). A psychologically rich life: Beyond happiness and meaning. Psychological Review, 129, 790–811.

Palmer, S., Cooper, C., & Thomas, K. (2004). A model of work stress to underpin the Health and Safety Executive advice for tackling work-related stress and stress risk assessments. Counselling at Work, 1, 2–5.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method bias in behavioural research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Porter, L., & Lawler, E. (1968). Managerial attitudes and performance. Dorsey.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Russo-Netzer, P., Icekson, T., & Zeiger, A. (2021a). The path to a satisfying life among secular and ultra-orthodox individuals: The roles of cultural background, gratitude, and optimism. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02206-4

Russo-Netzer, P., Horenczyk, G., & Bergman, Y. S. (2021b). Affect, meaning in life, and life satisfaction among immigrants and non-immigrants: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 40, 3450–3458.

Ryan, R. M., & Huta, V. (2009). Wellness as healthy functioning or wellness as happiness: The importance of eudaimonic thinking (response to the Kashdan at al. and Waterman discussion). The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 202–204.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations of the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93.

Steger, M. F., Oishi, S., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Meaning of life across the life span: Levels and correlates of meaning in life from emerging adulthood to older adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 43–52.

Thoits, P. A. (1991). On merging identity theory and stress research. Social Psychology Quarterly, 54, 101–112.

Thoits, P. A. (1992). Identity structures and psychological well-being: Gender and marital status comparisons. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55, 236–256.

Thoits, P. A. (2012). Role-identity salience, purpose and meaning in life, and well-being among volunteers. Social Psychology Quarterly, 75, 360–384.

Villa, J. R., Howell, J. P., Dorfman, P. W., & Daniel, D. L. (2003). Problems with detecting moderators in leadership research using moderated multiple regression. Leadership Quarterly, 14, 3–23.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Wayne, J. H., Randel, A., & Stevens, J. (2006). The role of identity and work-family support in work-family enrichment and its work-related consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 445–461.

Wayne, J. H., Grzywacz, J. G., Carlson, D. S., & Kacmar, K. M. (2007). Work-family facilitation: A theoretical explanation and model of primary antecedents and consequences. Human Resource Management Review, 17, 63–76.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective Events Theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior: An annual series of analytical essays and critical reviews (Vol. 18, pp. 1–74).

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to Niki Giatras for helpful discussions.

Funding

This research was supported by the Faculty of Business and Social Sciences at Kingston University, United Kingdom.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

E-mails inviting to participate in the study contained an explanation of the aim of the study, along with the assurance that participation would be voluntary, that respondents could withdraw from participating at any time, that their responses would be treated confidentially, and that data would be analysed at aggregate level. Potential respondents willing to participate accessed an online questionnaire through a link at the end of the invitation e-mail.

Conflict of interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wolfram, HJ. Meaning in life, life role importance, life strain, and life satisfaction. Curr Psychol 42, 29905–29917 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04031-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04031-9